Predicting Multiplayer Coordination

Some Theory, Some Lab, Some AIs

Experimental Class Fall, 2023

Taylor Weidman

Alistair Wilson

Marta Boczon

Emanuel Vespa

Motivation

- Repeated games are used to model ongoing economic interactions across fields

- But theory is not predictive: Folk theorems, while elegant, are essentially negative results

- Experiments have focused on understanding selection in starkest setting: repeated prisoner's dilemma (RPD)

- Larger Question: Can we build outward from what we know about selection in the RPD to other games/moving parts?

Equilibrium Selection

- Consider an applied researcher with data and a structural model

When will equilibrium selection matter?

- Using the data to recover structural parameters under assumed equilibrium

-

When she uses estimated parameters to predict a counterfactual

- Policy changes can shift selected equilibrium

- Hard to predict if counterfactuals involve shifts to more than one variable

Stylized Example

Broadly matching our initial treatment variation, consider:

Net directional effect from consolidation unclear:

- Efficiency gains might spur competition (Prices: \(\downarrow\))

- Collusion easier with smaller number of firms (Prices: \(\uparrow\))

With competing effects, need a theory capable of assessing the scale of the competing effects to get direction

- Industry with many price-competing firms

- Push for merger-friendly legislation

- Broad agreement that current market not collusive

Predicting Selection

One candidate for predicting selection is the Basin of Attraction:

Idea:

- Measure the critical belief on the other conditionally cooperating, where conditional cooperation becomes a best response

Index measure of strategic uncertainty

as summary of the competing forces.

- Originally developed for static/normal-form games

- Adapted for RPD by Blonksi & Spagnolo (2015)

- Empirical relevance shown in Dal Bo & Frechette (2011)

Predicting Selection

Pros:

- Theoretically tractable

- Extension to new environments clearer

- Already validated in starkest dynamic setting

Cons:

- Only validated in starkest dynamic setting

- Some extensions will have multiple options

- World is complicated, maybe there is no one-size approach

What we do in this paper

But to what extent can we think of calibrated (and opposing) shifts in these variables as direct substitutes?

- Examine extension of the Basin of Attraction to \(N\)-players

- Examine changes in two primitives as affecting strategic uncertainty:

- increasing temptation increases basin for defection

- increasing \(N\) increases basin for defection

- Introduce the basin-of-attraction index for the two player RPD

- Discuss different ways to extend standard two-player RPD

- Present experimental design

- Tests which extension best rationalizes behavior

- Results

- Discussion

- Extensions and Robustness: Details

- Predicting AI pricing agents

Rest of the Talk

A large experimental literature has examined how participants behave in the canonical environment for examining implicit coordination/cooperation:

- Repeated Prisoner's Dilemma game

What we do

While many experiments find that implicit cooperation is commonplace and predictable, implicit collusion is thought to be less common in IO settings (where explicit collusion is thought to be more common)

- However, a newer literature in IO examines the extent to which AI pricing agents engage in implicit collusion.

Meta-study of RPD

Summary of Literature

The broad conclusions from the repeated prisoner's dilemma literature (summarized in the meta study):

- Human subjects use implicit cooperation/collusion often through simple dynamic strategies.

- Equilibrium existence is only a necessary condition

- For cooperation to be observed, the risk in coordination needs to be small relative to the gains

- Behavior can broadly be summarized as a mix across three simple (sub-memory-one) strategies:

- Always Defect

- Tit-for-Tat

- Grim trigger

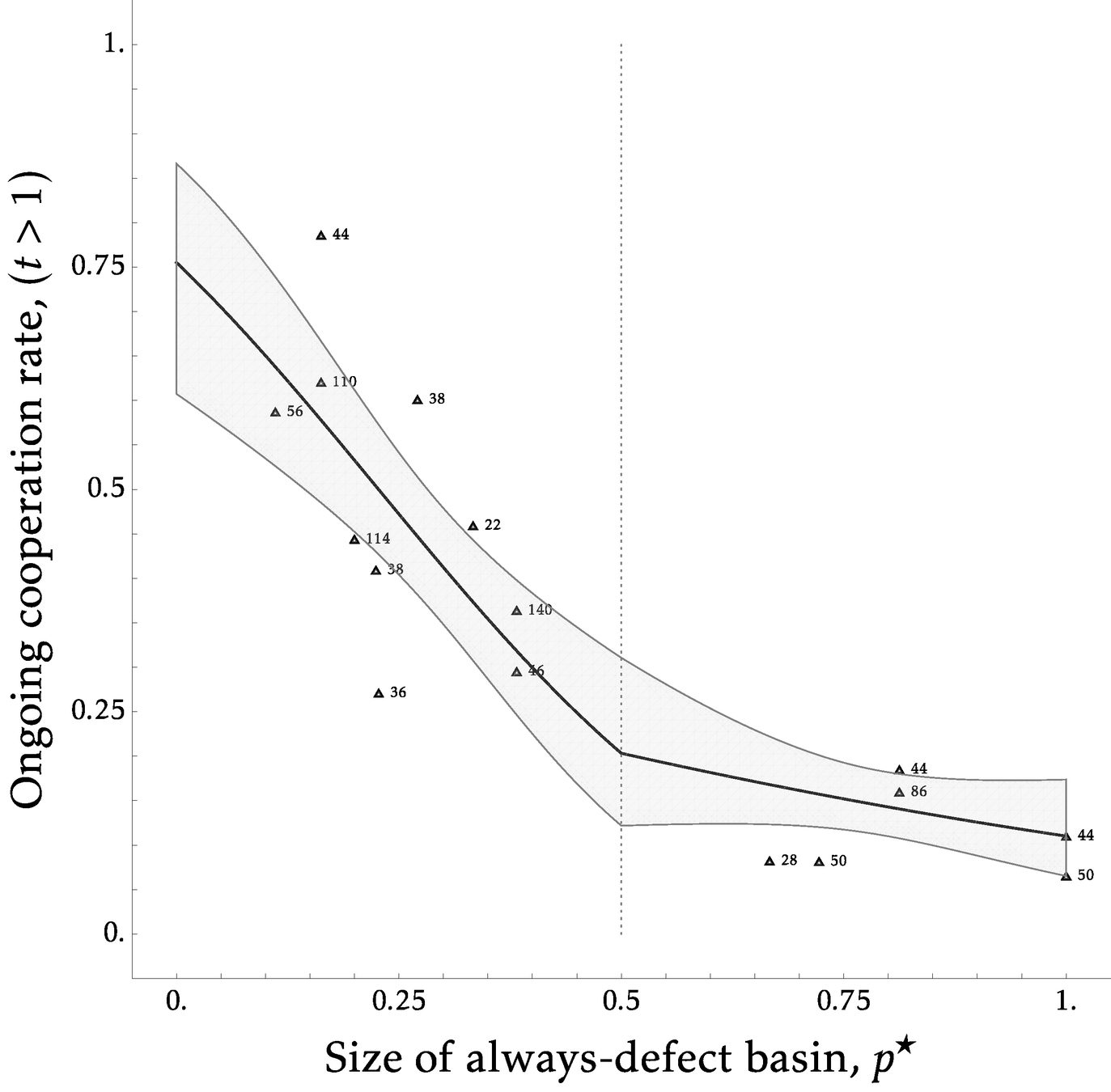

While much of the experimental meta-study is descriptive, one thrust is outlining how a theoretic measure is predictive over observed cooperation levels:

Theoretical measures are useful here as:

- Can extend across environments

- Allow us to make counterfactual predictions that take selection into account

Theoretic Selection Criteria

The Size of the Basin of attraction for Always Defect provides a balance between tractability and extensibility. Looks at two simple (and extreme) strategic responses:

- Cooperative Grim Trigger (Eff. SPE)

- Always Defect (Ineff. MPE)

Basin of Attraction

Assuming the world is captured entirely by the tradeoff across these two extreme responses we can go from any stage game to a critical probability for the other cooperating

Theoretic Criteria

| (R, R) | (S, T) |

| (T, S) | (P,P) |

C

D

C

D

Grim

AllD

Grim

AllD

\((R,R)\)

\((V_S,V_T)\)

\((V_T,V_S)\)

\((P,P)\)

So the theory is a constructable function of the primitives, and \(p^\star\) serves as a decreasing index for cooperation

- However, this is over-parameterized, need to normalize and rescale (Measure relative to \(P\) in units of \(R-P\))

Theoretic Criteria

Grim

AllD

Grim

AllD

\((1,1)\)

\((V_S,V_T)\)

\((V_T,V_S)\)

\((0,0)\)

For the RPD the Basin size \(p^\star\) is a function of three parameters:

1. Temptation \(t\); 2. Sucker cost \(s\); 3. Discount \(\delta\)

| (1, 1) | (-s, 1+t) |

| (1+t, -s) | (0,0) |

C

D

C

D

Experimental RPD Results

Dal Bo and Frechette meta-study comparative statics:

- Discount Rate: \(\delta\uparrow \Rightarrow \text{Coop}\uparrow\) (\(p^\star\downarrow\))

- Temptation, \(T^\prime\uparrow\Rightarrow\text{Coop}\downarrow\) (\(p^\star\uparrow\))

- Sucker's payoff \( S^\prime\uparrow\Rightarrow\text{Coop}\downarrow \) (\(p^\star\uparrow\))

Main empirical outcomes considered:

- Cooperation rate in the first supergame round (individual measure)

- Ongoing cooperation (all rounds) also considered

- For the selection model this is just \(\text{(first round rate)}^2\) for all parameters \((\delta, T^\prime, S^\prime)\)

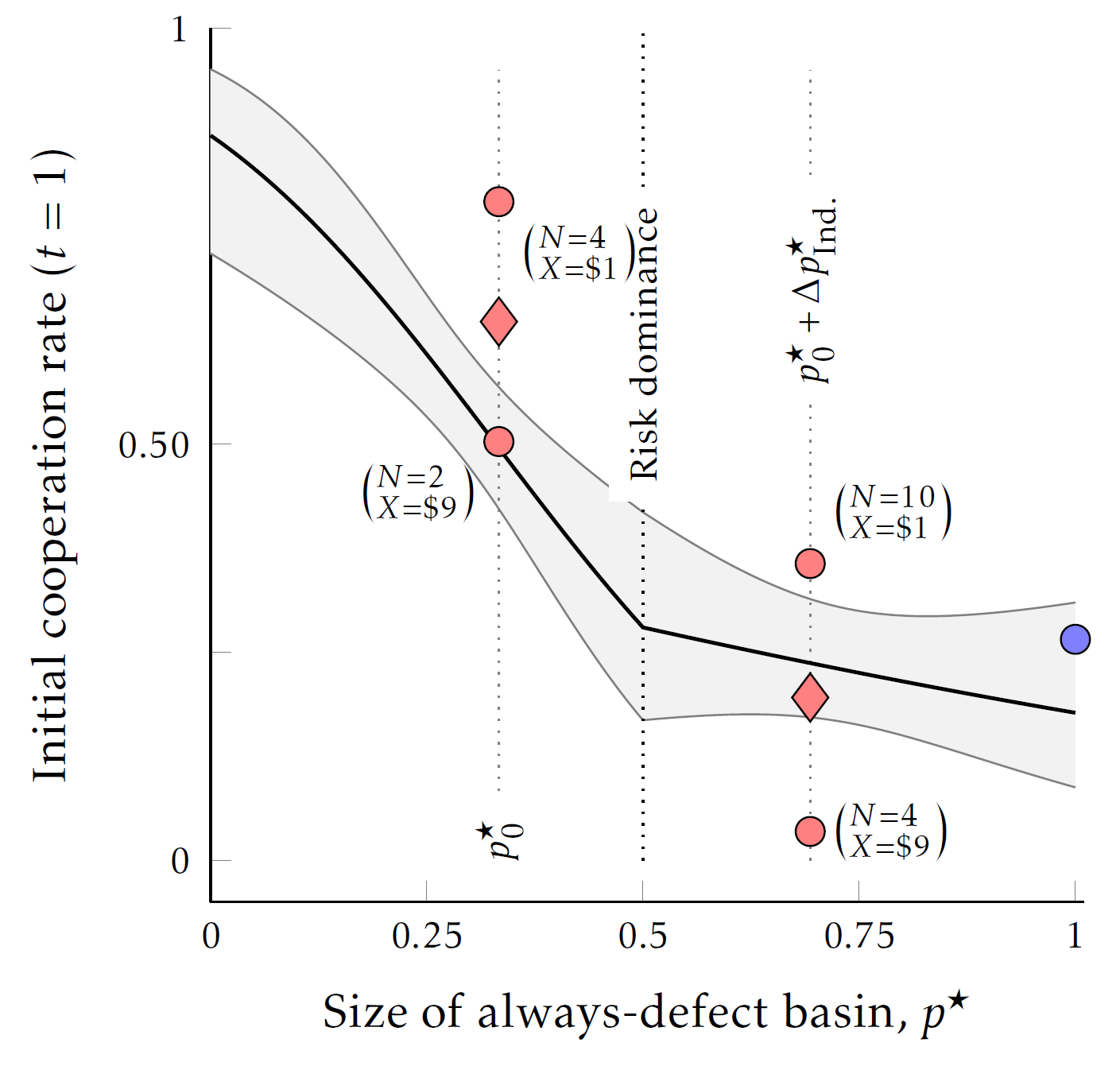

But can the basin predict differential tradeoffs of each?

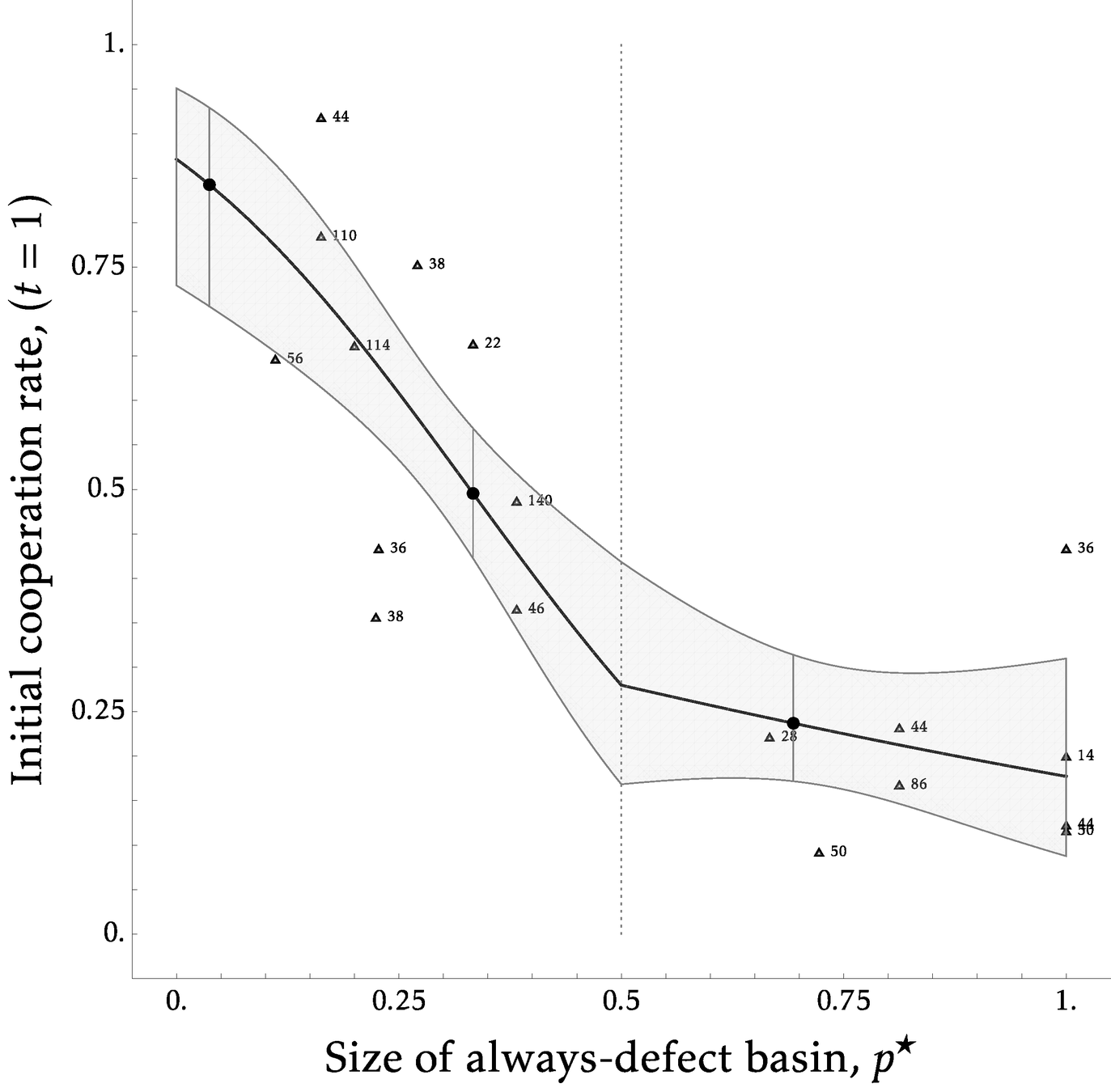

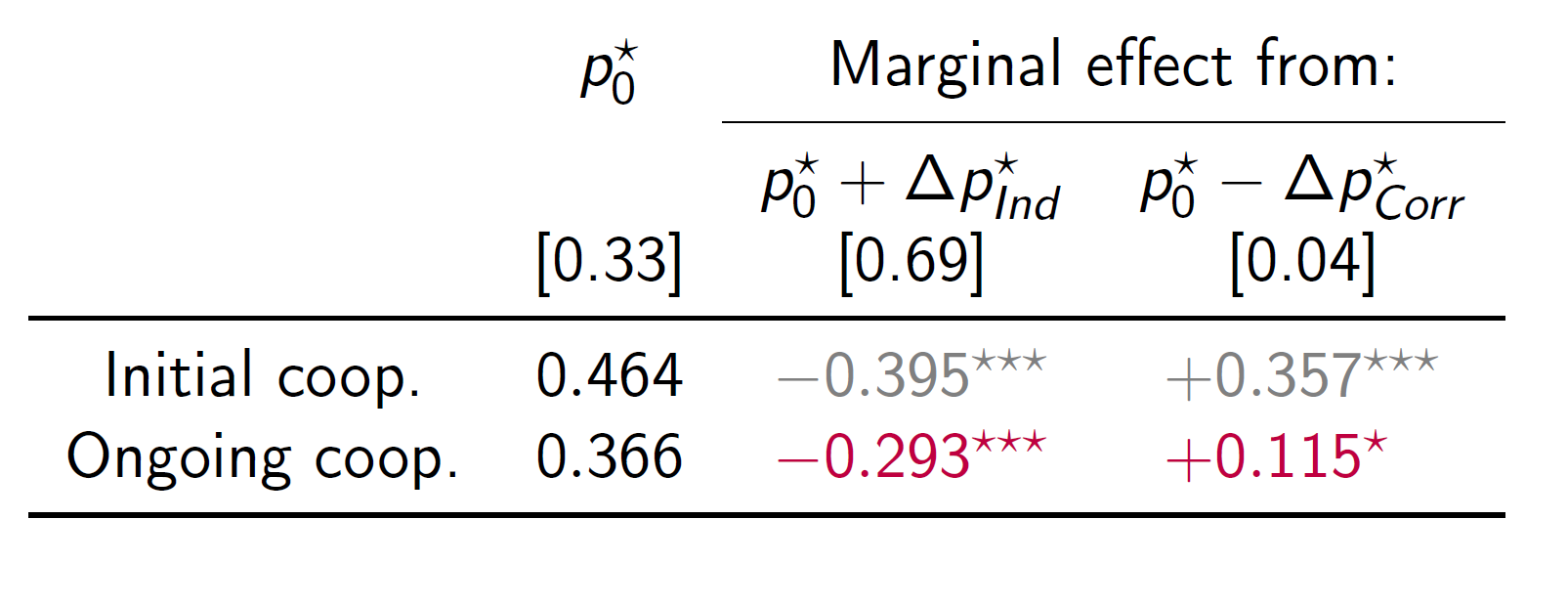

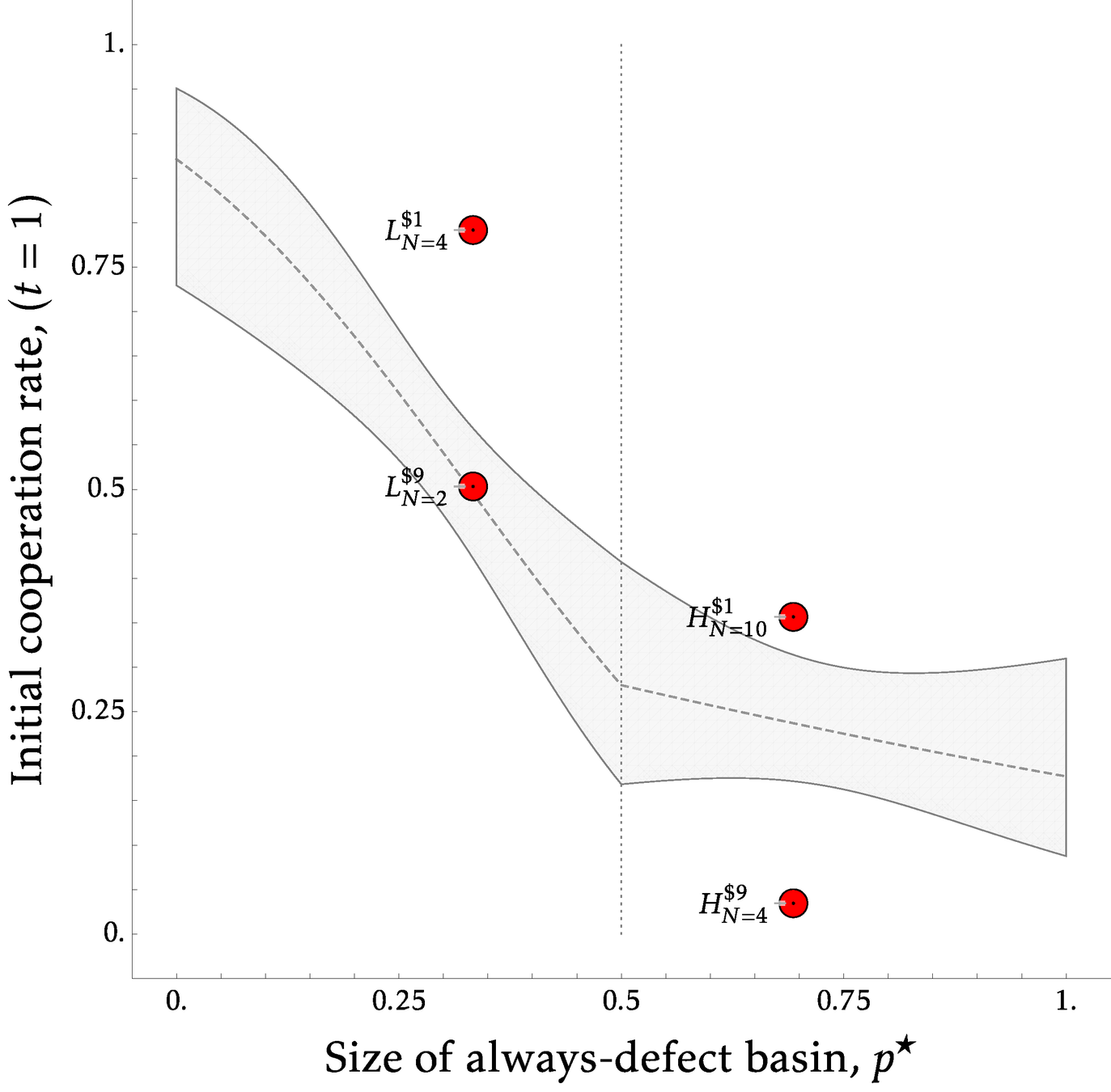

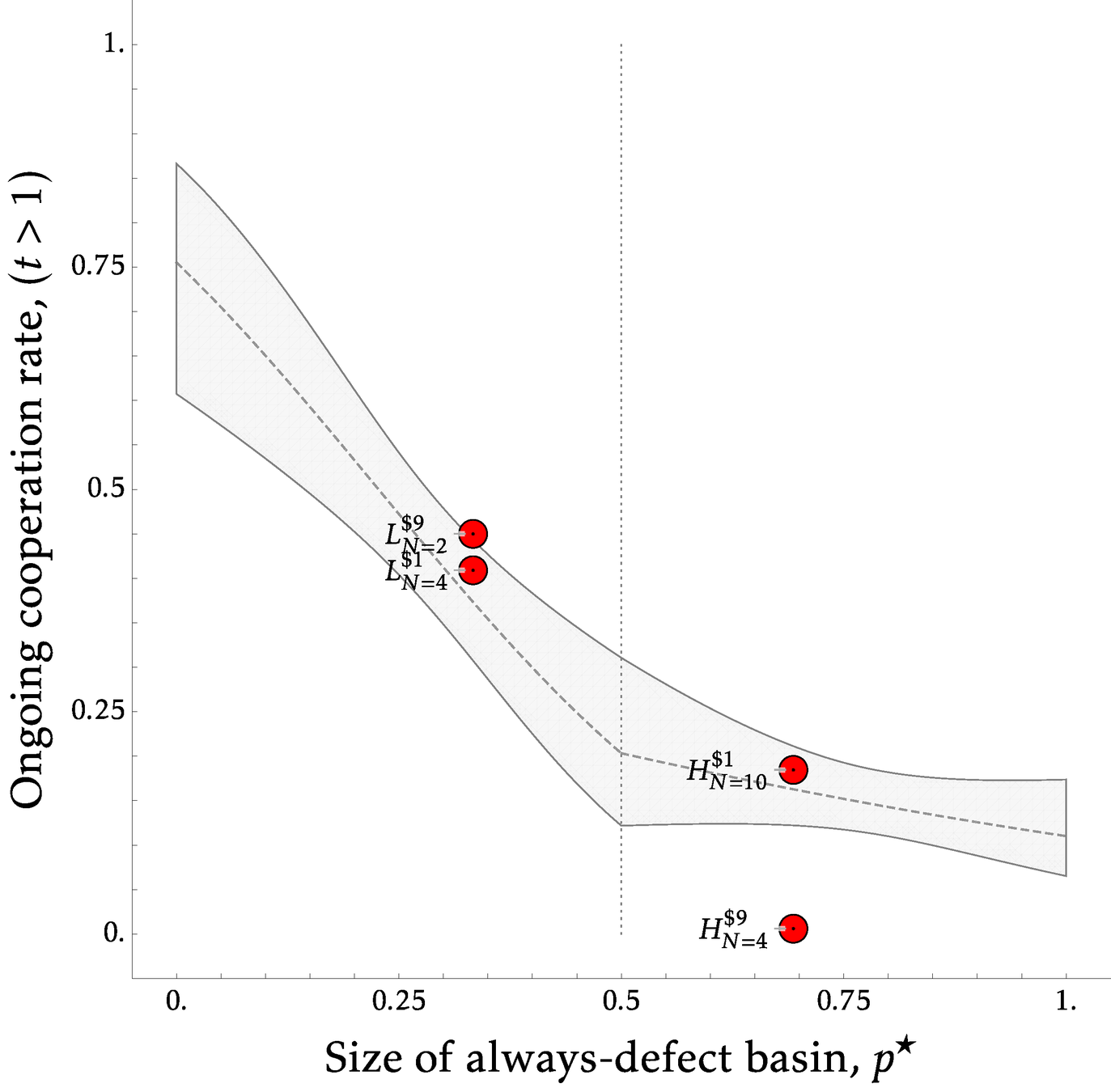

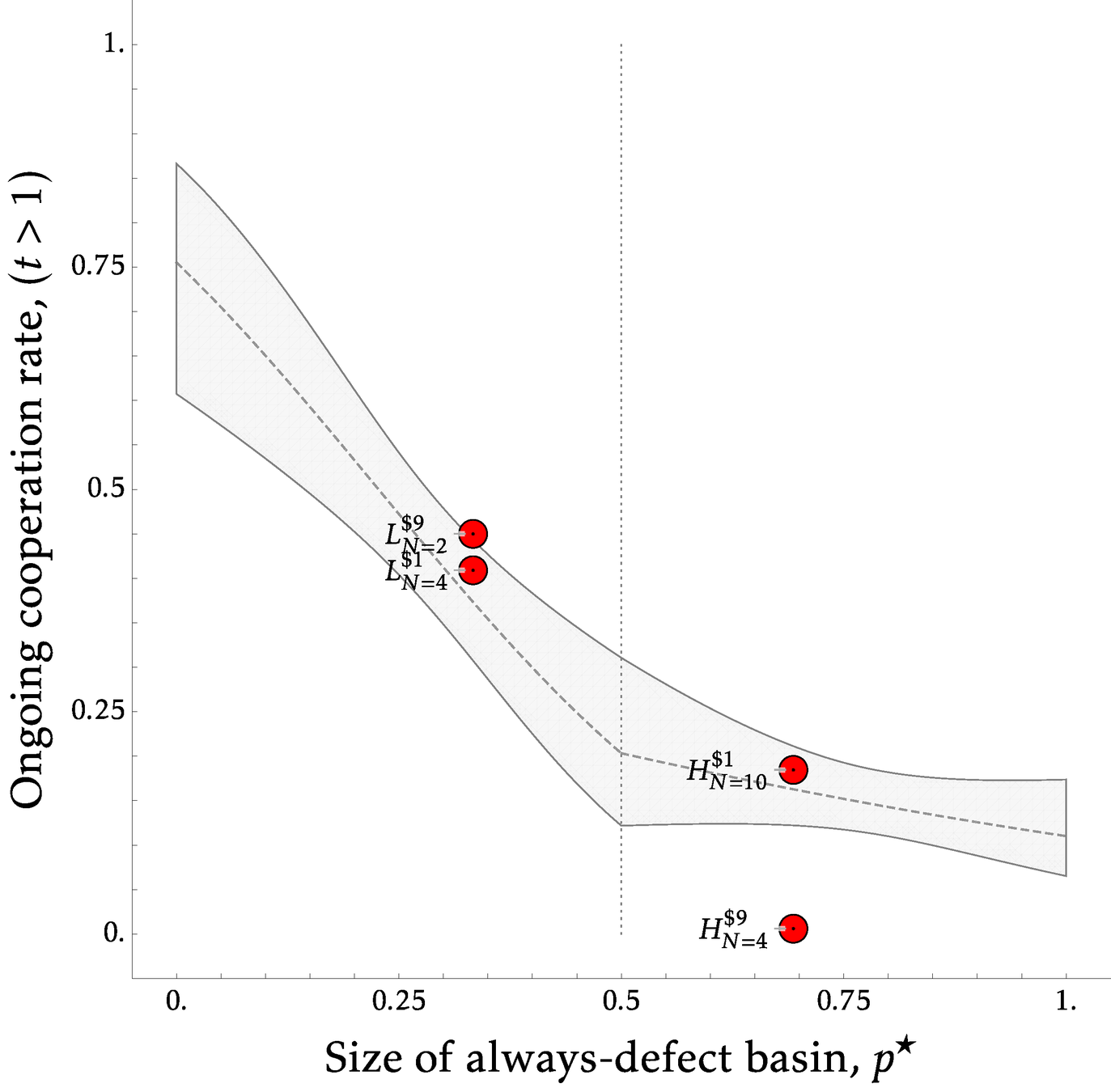

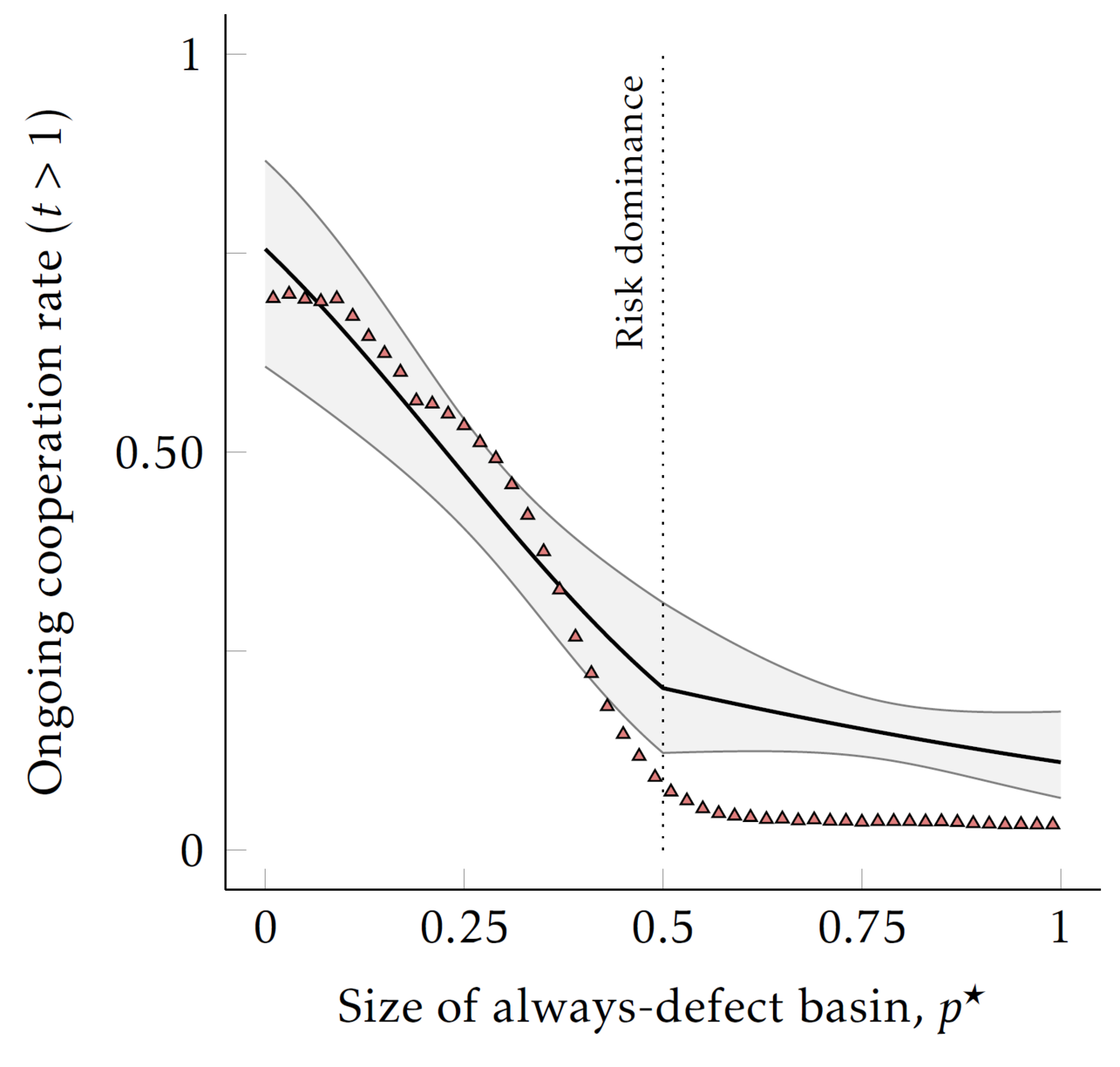

Empirical Relationship

\(\leftarrow\)Coop Risk Dom.

\(\leftarrow\)Existence

Beyond the RPD: Generalizing to \(N\)

Our questions:

- How can we extend the basin of attraction in \(N\) player games?

- Does any extension have empirical support?

- Are there other populations we can examine?

Extension to \(N\)-player RPD

| 1 | -s |

| (1+t) | 0 |

C

D

C

D

| 1 | -x |

| 1+x | 0 |

C

D

All C

Not All C

\(\left(N-1\right)\) others

You:

Other:

If your model of the others is that they act monolithically, then the formula is identical to the RPD:

Extension to \(N\)-player RPD

\(\left(N-1\right)\) others

You:

Other:

If your model of others is that they act independently, then the Basin-size gets larger with \(N\):

| 1 | -X |

| 1+X | 0 |

C

D

All C

Not All C

| 1 | -S |

| 1+T | 0 |

C

D

C

D

Experimental Game

- Experiment uses Green/Red for action labels

- Multiply by $9 and add $11

- \(x\) is either $9 or $1

- \(\delta=\frac{3}{4}\) is continuation probability

- Only last round in supergame paid

| $20 | $11-$x |

| $20+$x | $11 |

Green

Red

All Green

One or more Red

\(\left(N-1\right)\) others

You:

Experimental Game (\(X=\$9\))

| $20 | $2 |

| $29 | $11 |

Green

Red

All Green

One or more Red

\(\left(N-1\right)\) others:

You:

Experimental Game (\(X=\$1\))

| $20 | $10 |

| $21 | $11 |

Green

Red

All Green

One or more Red

\(\left(N-1\right)\) others:

You:

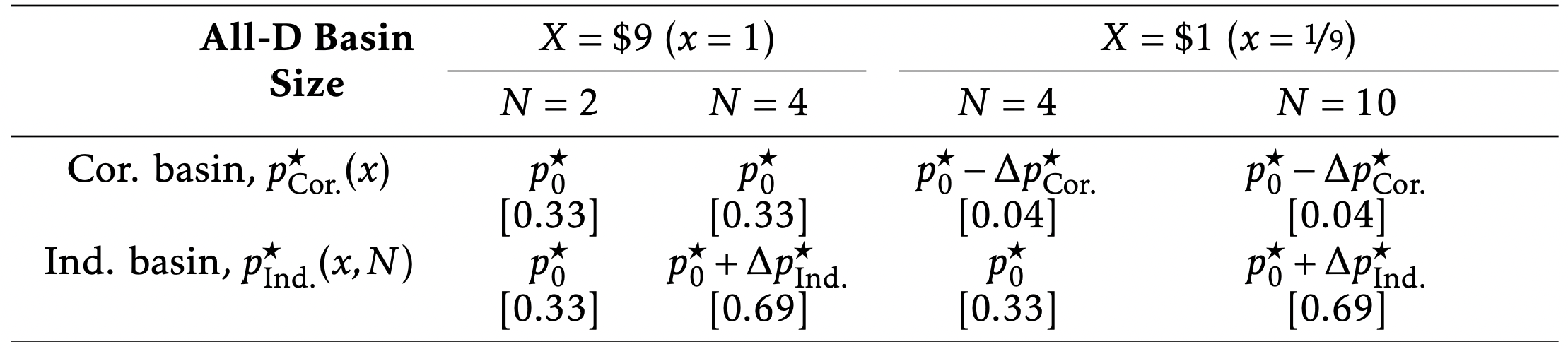

Design Idea

Start with a baseline level of strategic uncertainty \(p_0\)

- Do this at \(p_0=\tfrac{1}{3}\) for a standard RPD with \(X=\$9\) and \(N=2\)

Using variation in both \(X\) and \(N\) we then separately manipulate the correlated and independent basins:

- With \(X=\$9\) , \(N=4\) \(\Rightarrow\) \(p_\text{Cor}=p_0\), \(p_\text{Ind}=p_0+\Delta p_I\)

- With \(X=\$1\) , \(N=4\) \(\Rightarrow\) \(p_\text{Cor}=p_0-\Delta p_C\), \(p_\text{Ind}=p_0\)

- With \(X=\$1\) , \(N=10\) \(\Rightarrow\) \(p_\text{Cor}=p_0-\Delta p_C\), \(p_\text{Ind}=p_0+\Delta p_I\)

Design Idea

Effectively the correlated basin is the null hypothesis over movement in \(N\), focusing just on the independent basin we have:

- With \(X=\$9\) , \(N=2\) \(\Rightarrow\) \(p_\text{Ind}=p_0\)

- With \(X=\$9\) , \(N=4\) \(\Rightarrow\) \(p_\text{Ind}=p_0+\Delta p_I\)

- With \(X=\$1\) , \(N=4\) \(\Rightarrow\) \(p_\text{Ind}=p_0\)

- With \(X=\$1\) , \(N=10\) \(\Rightarrow\) \(p_\text{Ind}=p_0+\Delta p_I\)

As such, the Independent basin gives us a \(2\times 2\) design over two basin sizes

Design Idea

- Independent Basin: Should only within \(x\) effects

- Correlated Basin: Should only across \(x\) effects

Details

-

Each treatment runs for 20 supergame repetitions

-

Split into two identical 10-supergame halves

-

-

Three sessions of each treatment

-

20/24 University of Pittsburgh UG subjects

-

-

Paid for last round in two randomly selected supergames

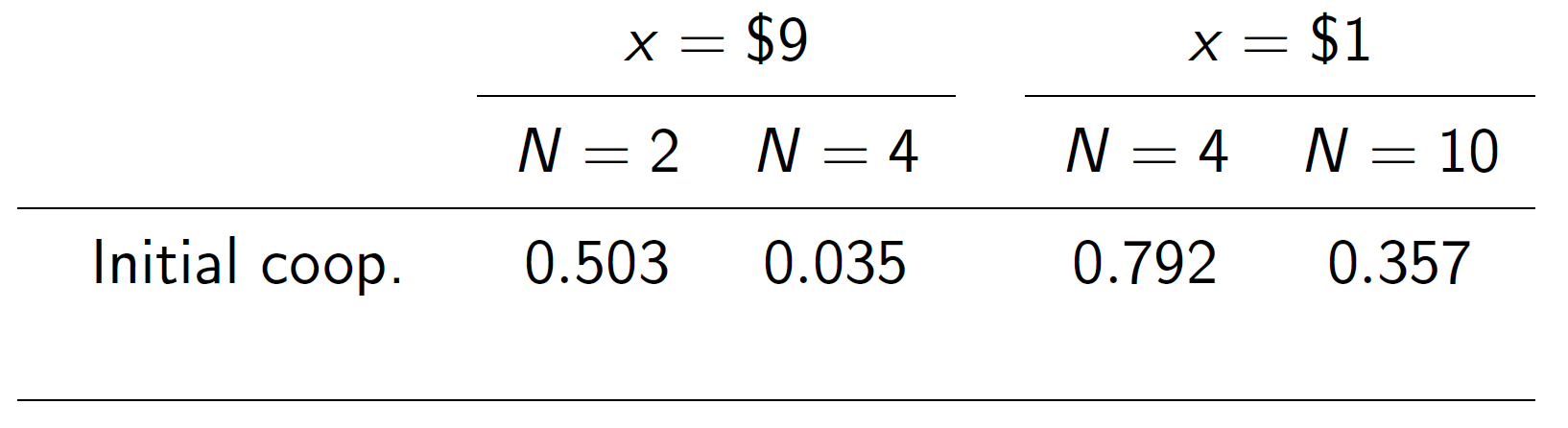

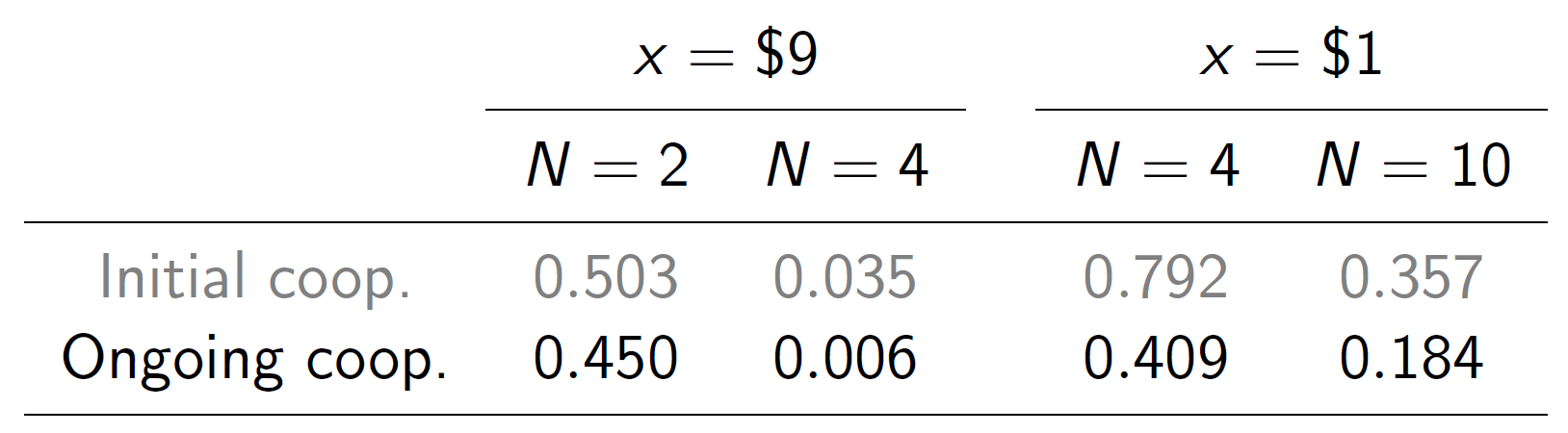

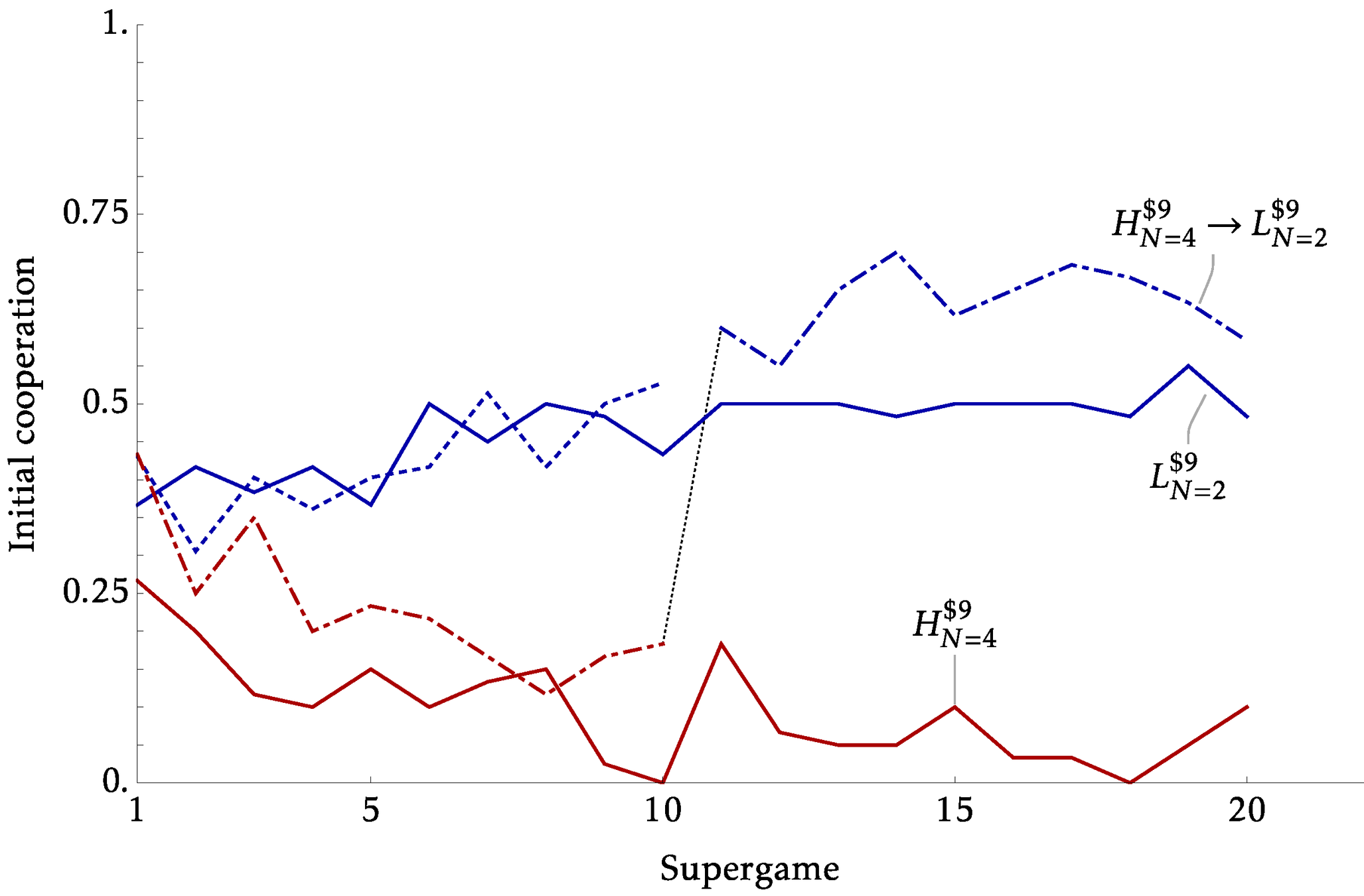

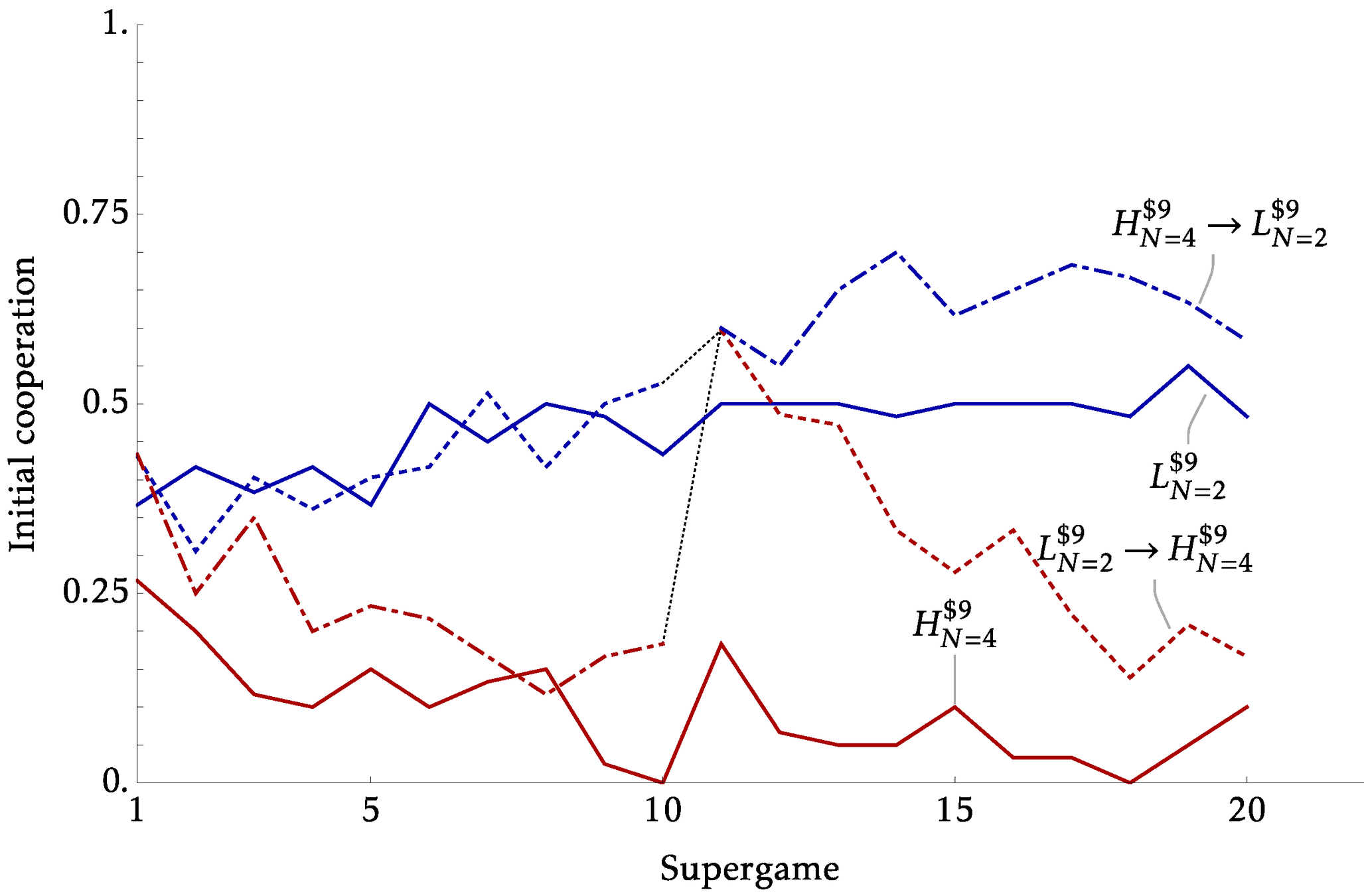

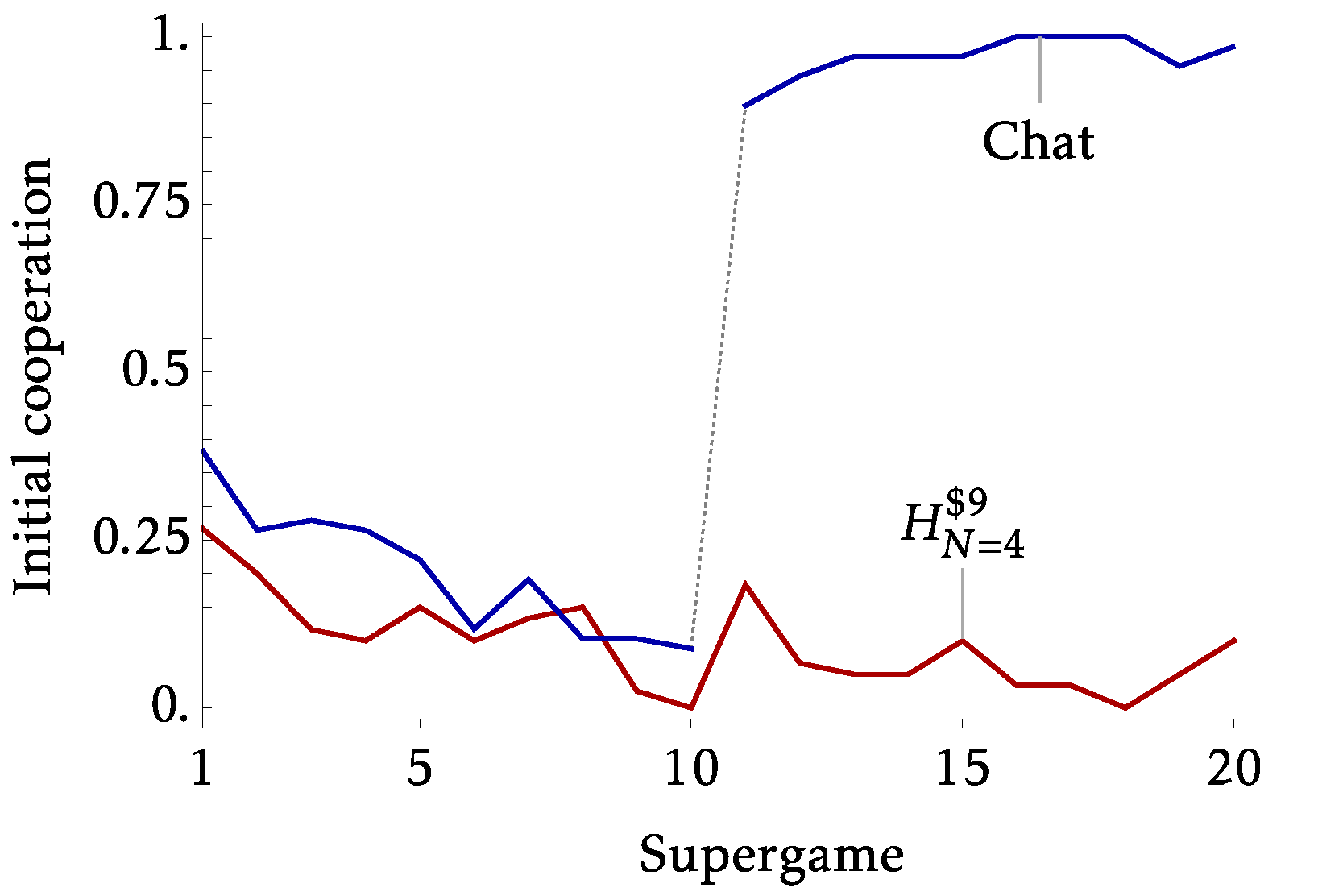

Results

Results

Results

So we validate the extended theory within our game only for ongoing cooperation

Results

So we validate the extended theory within our game only for ongoing cooperation

Extensions

- Within subject identification

- Explicit Collusion

- Alternative game environment

- Predicting AI agents

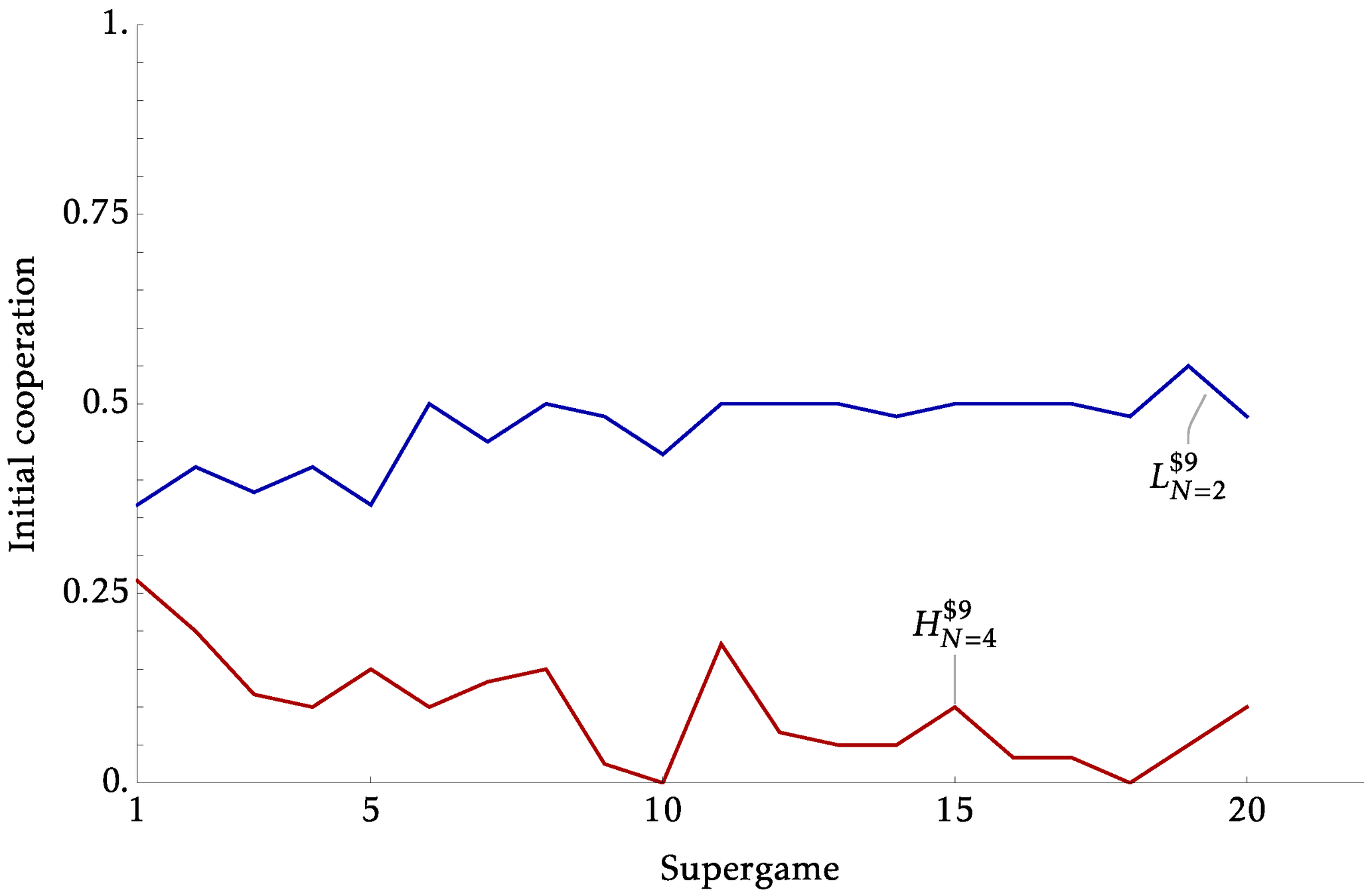

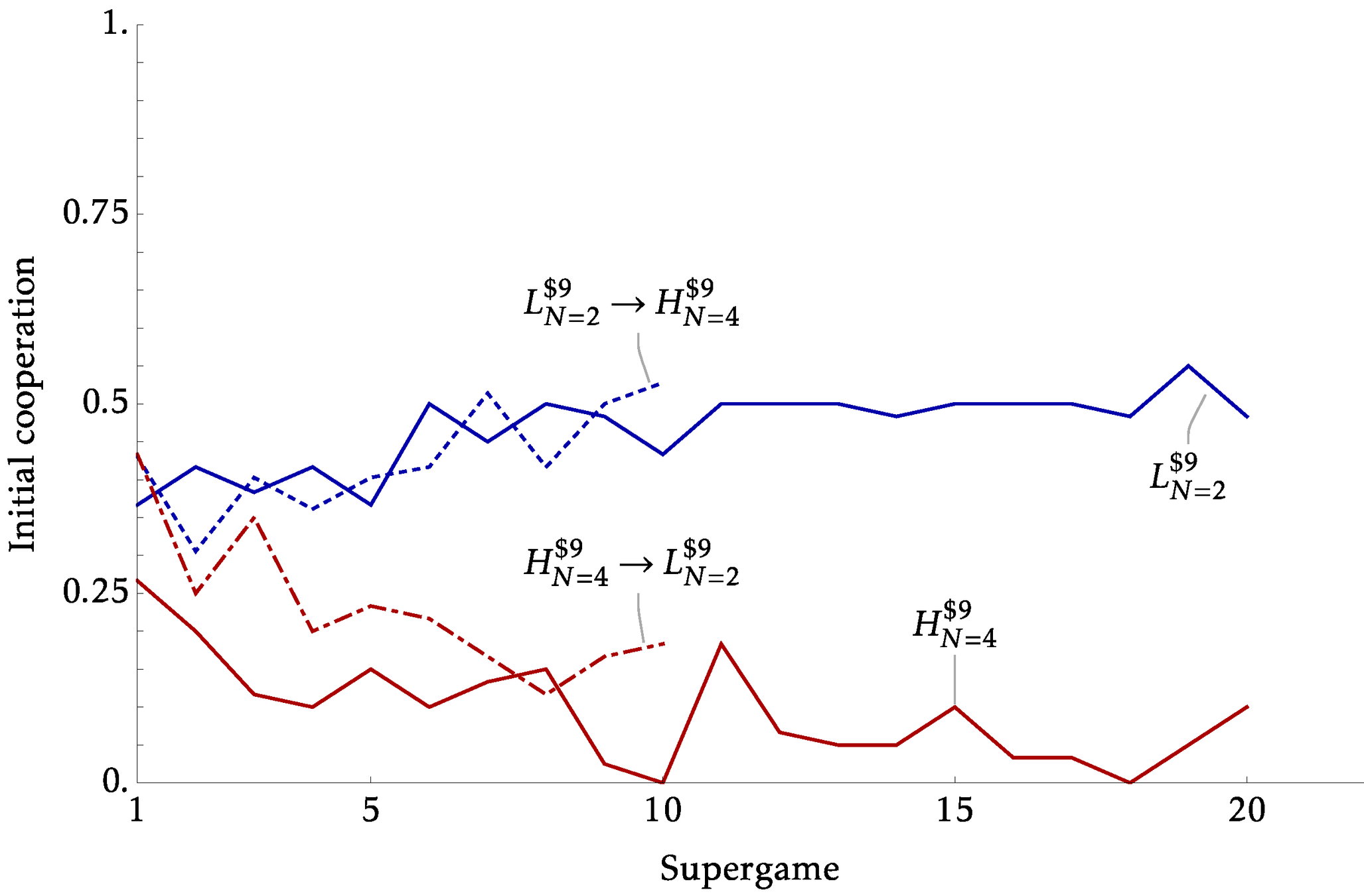

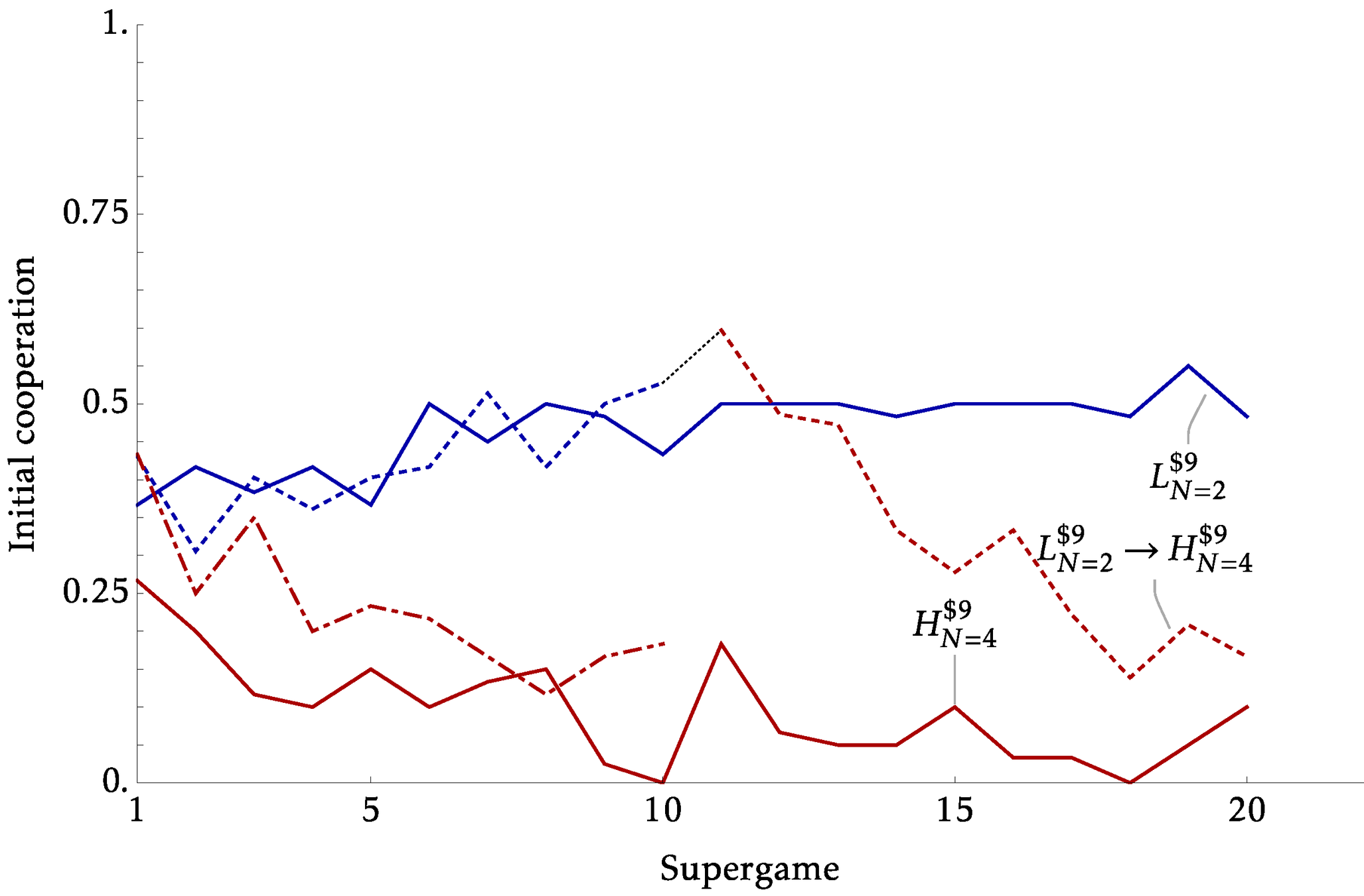

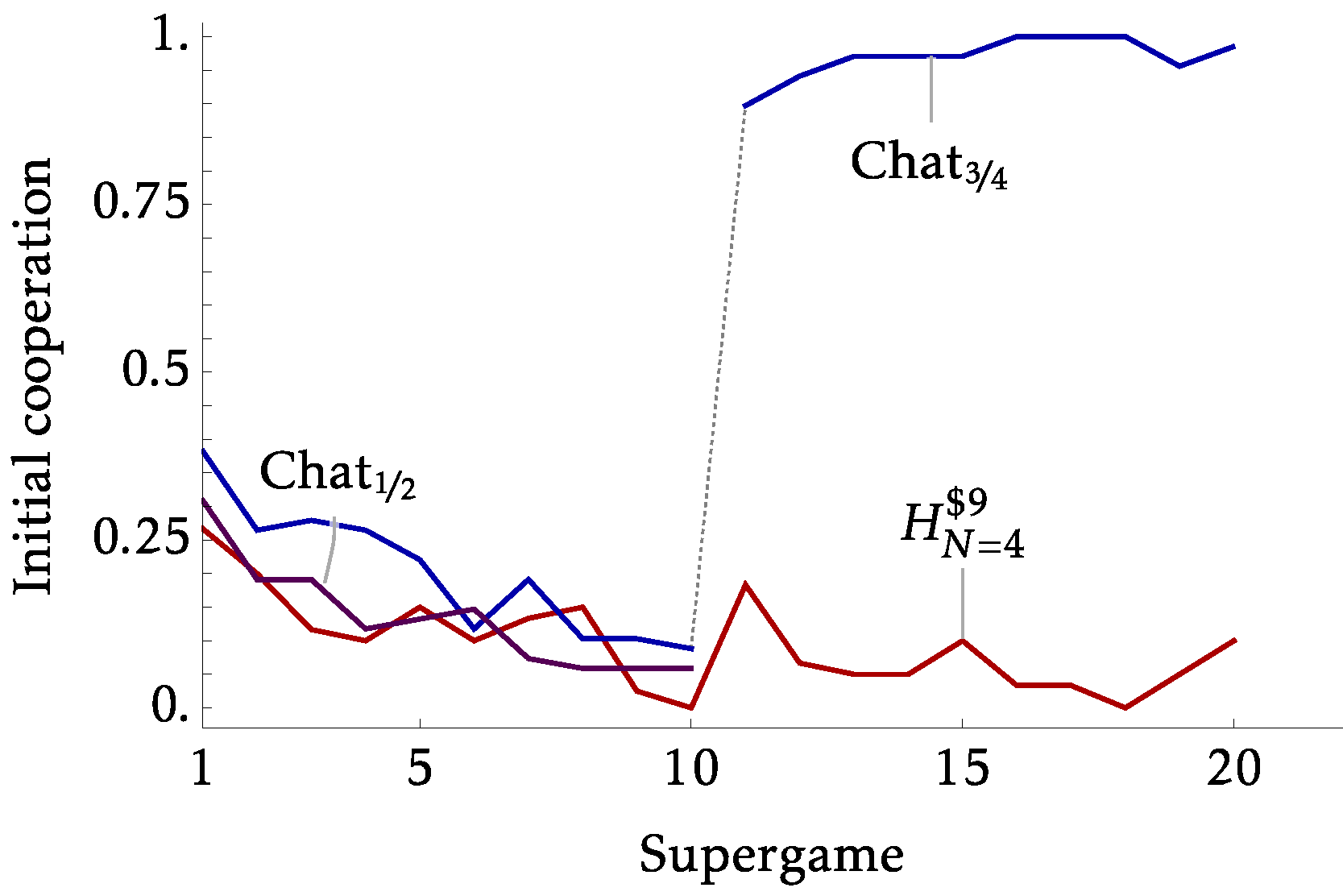

Between vs Within Identification

- The previous experiments identify the effects from \(x\) and \(N\) using distinct sessions. Creating two parallel worlds under different conditions

- But many policy counterfactuals will essentially be within

- This can be a substantive critique for models based on strategic uncertainty and belief

- Our experiments began with this in mind, where we have two parts of 10 supergames.

- In our Within sessions, we hold \(X=\$9\) but:

- Expanding: Part 1 \(N=2\) , Part 2 \(N=4\)

- Consolidating: Part 1 \(N=4\) , Part 2 \(N=2\)

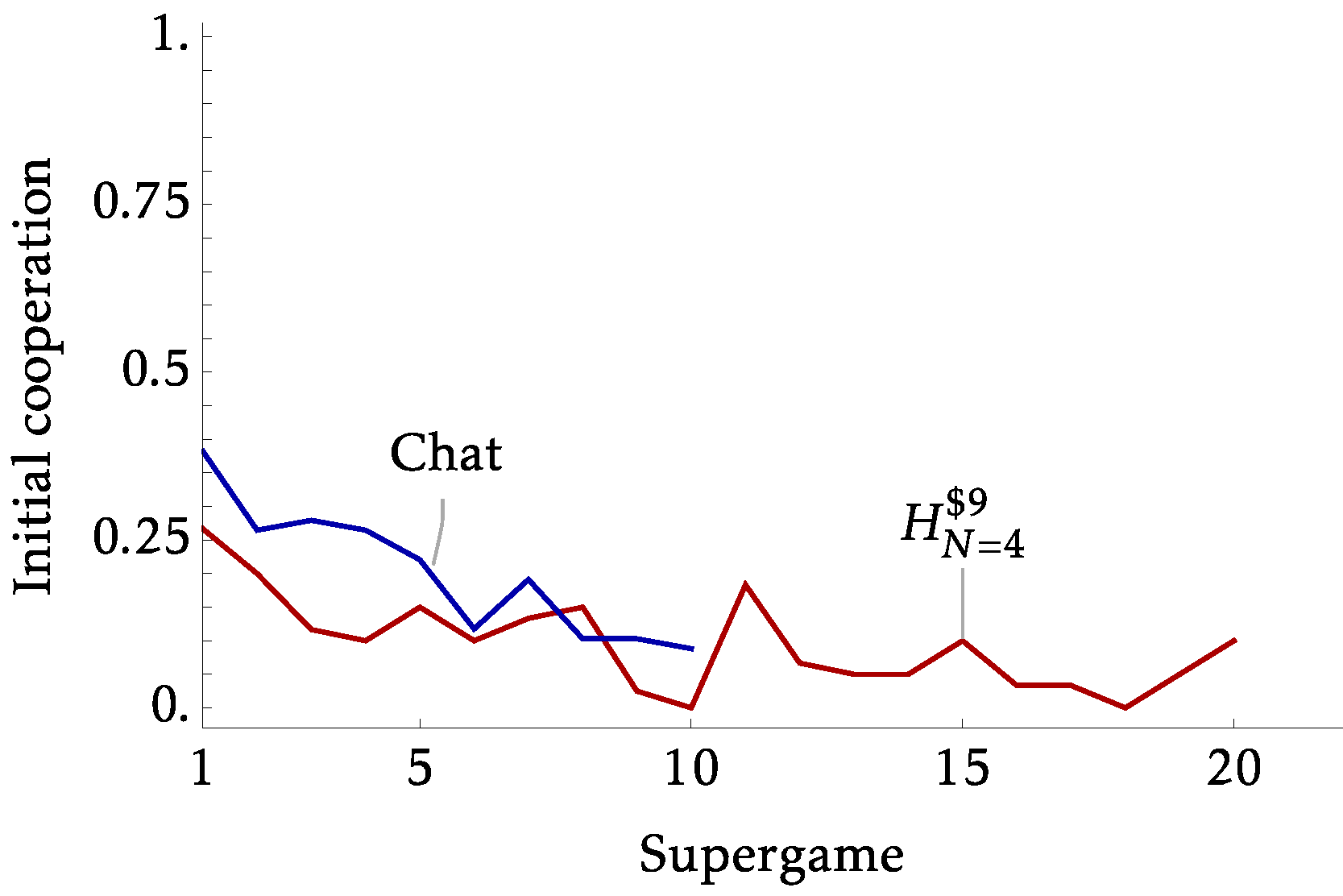

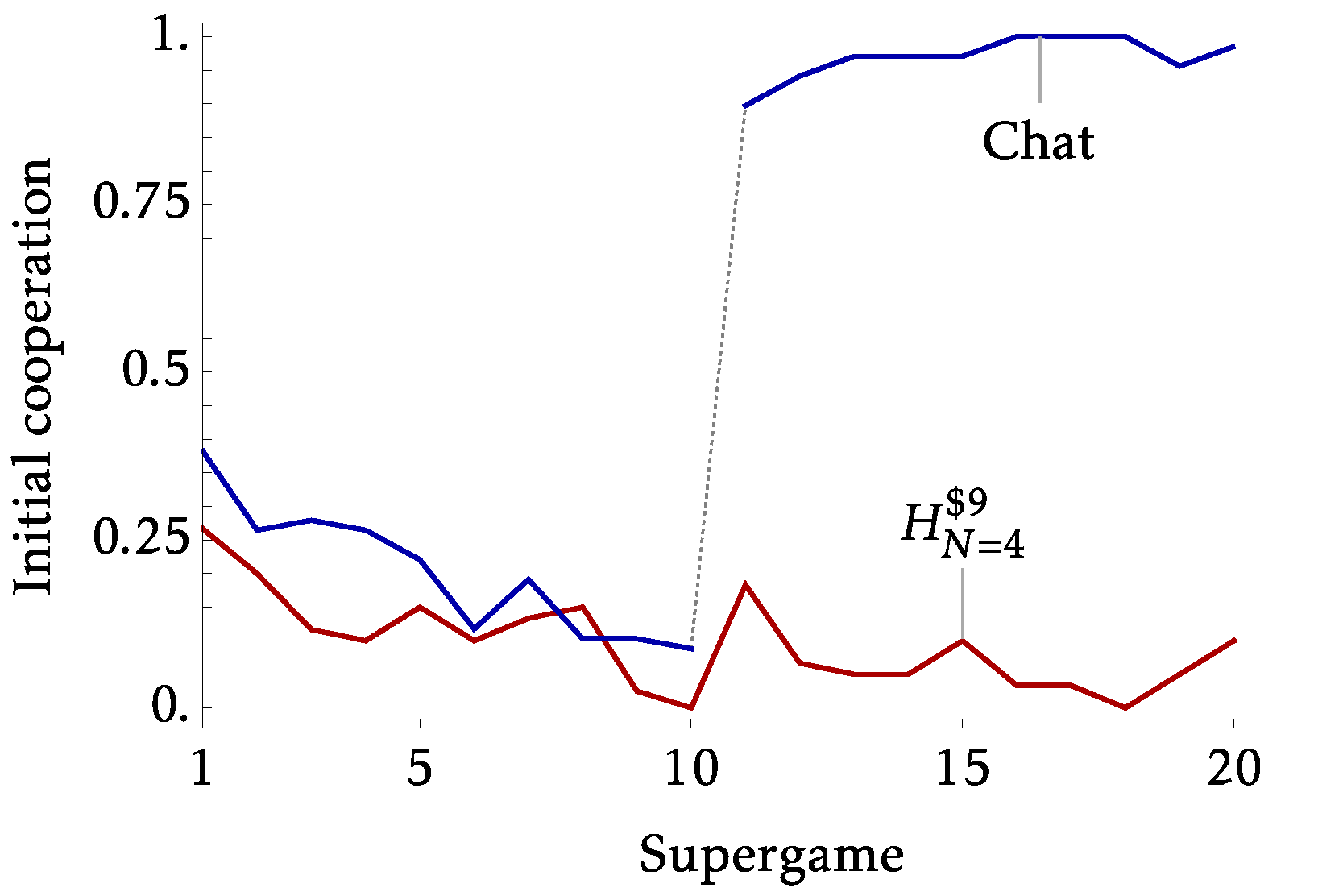

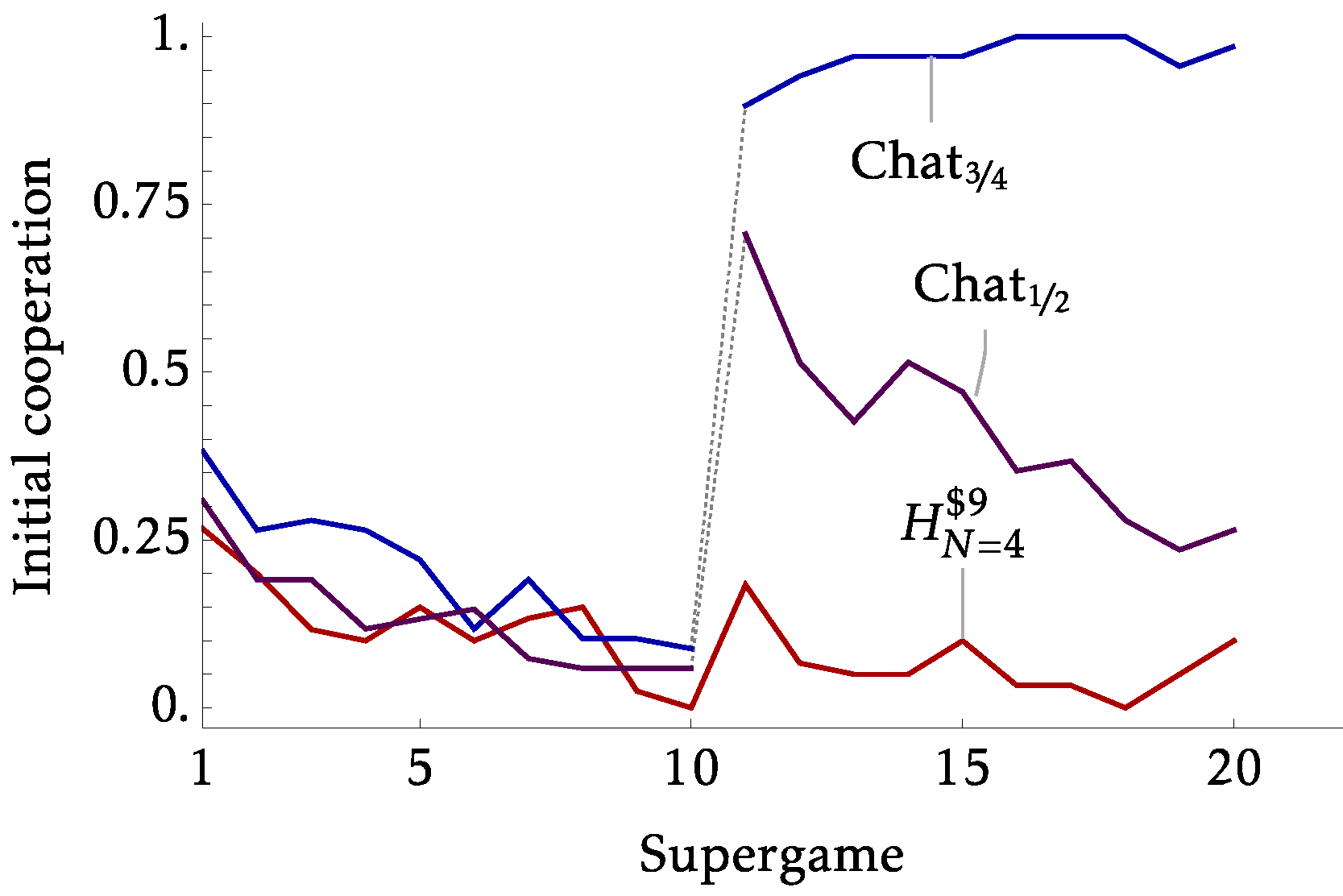

Explicit Communication

- So far findings suggest that strategic uncertainty as captured by the independent extension can predict ongoing cooperation

- Can we learn a bit more about strategic uncertainty?

- It can capture:

- Coordination Uncertainty

- Trust Issues

- Both

- Introduce a treatment with chat

- Strong coordination device

- Chat only available pre-play. So any trust issues remain.

- By 'Strategic Uncertainty' we likely capture 'Coordination Uncertainty'

- Given a strong coordination device, the extension index is no longer a useful predictive tool, which makes sense

- Perhaps communication fixes things it shouldn't

Game Form Stress Test

- So at \(N=4\) this game has the same requirement for stable cooperation as our \(N=2\) environment

- But both basin calculations suggest that it is substantially harder to coordinate on

- Both Independent and Correlated basin size is 1

- Only equilibria involve asymmetric behavior

| $20 | $2 |

| $29 | $11 |

Green

Red

All Green

One+ Red

\(\left(N-1\right)\) others

You:

| $20 | $2 |

| $29 | $11 |

Green

Red

One+ Green

All Red

\(\left(N-1\right)\) others

You:

Results

- In terms of successful coordination rates our original treatments with \(x=\$9\) had initial rates of:

- \(N=2\) : 45%

- \(N=4\) : 0%

- Ongoing success of:

- \(N=2\) : 40%

- \(N=4\) : 0%

- New treatment that only requires one other person to cooperate for a success:

- Initial: 30%

- Ongoing: 22%

Initial cooperation rate:

Which brings us to the AIs

- While human-subject behavior does suggest a predeliction for implicit coordination, the empirical IO literature has been more focused on explicit coordination

- However, that seems to be changing with a new literature that suggests that basic off-the-shelf AI pricing algorithms quite readily collude with one another

Which brings us to the AIs

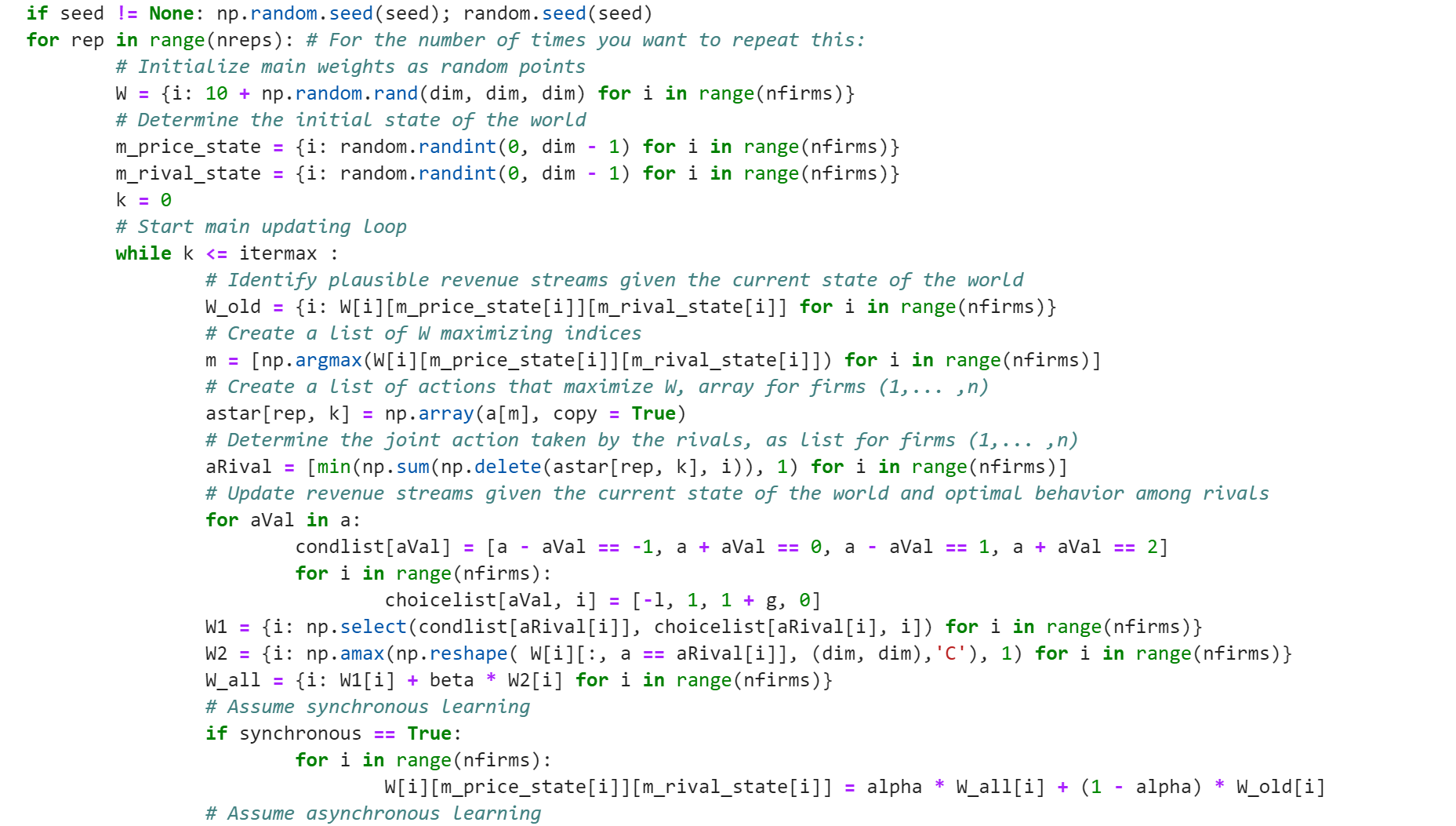

Q-learning

Type of reinforcement learning allowing for dynamic response across the available actions \(a_1,\ldots,a_n\) and across states \(\omega_1,\ldots,\omega_n\)

Chosen actions determined by maximal weight Updated weights on realized outcomes are scaled up/down according to the payoffs. The system (with multiple independent agents) is then allowed to converge to a steady state.

The form of the algorithm's update rule is important for these conclusions:

- Asynchronous (update only on observation)

- Synchronous (update counterfactuals too)

Asynchronous updates just the chosen action

Synchronous also updates unchosen actions based on the counterfactual

Synchronous updating requires a model of the world to do additional learning over. Asker et al. papers demonstrate that even relatively simple models (downward-sloping demand say) lead to substantial reductions in collusive behavior.

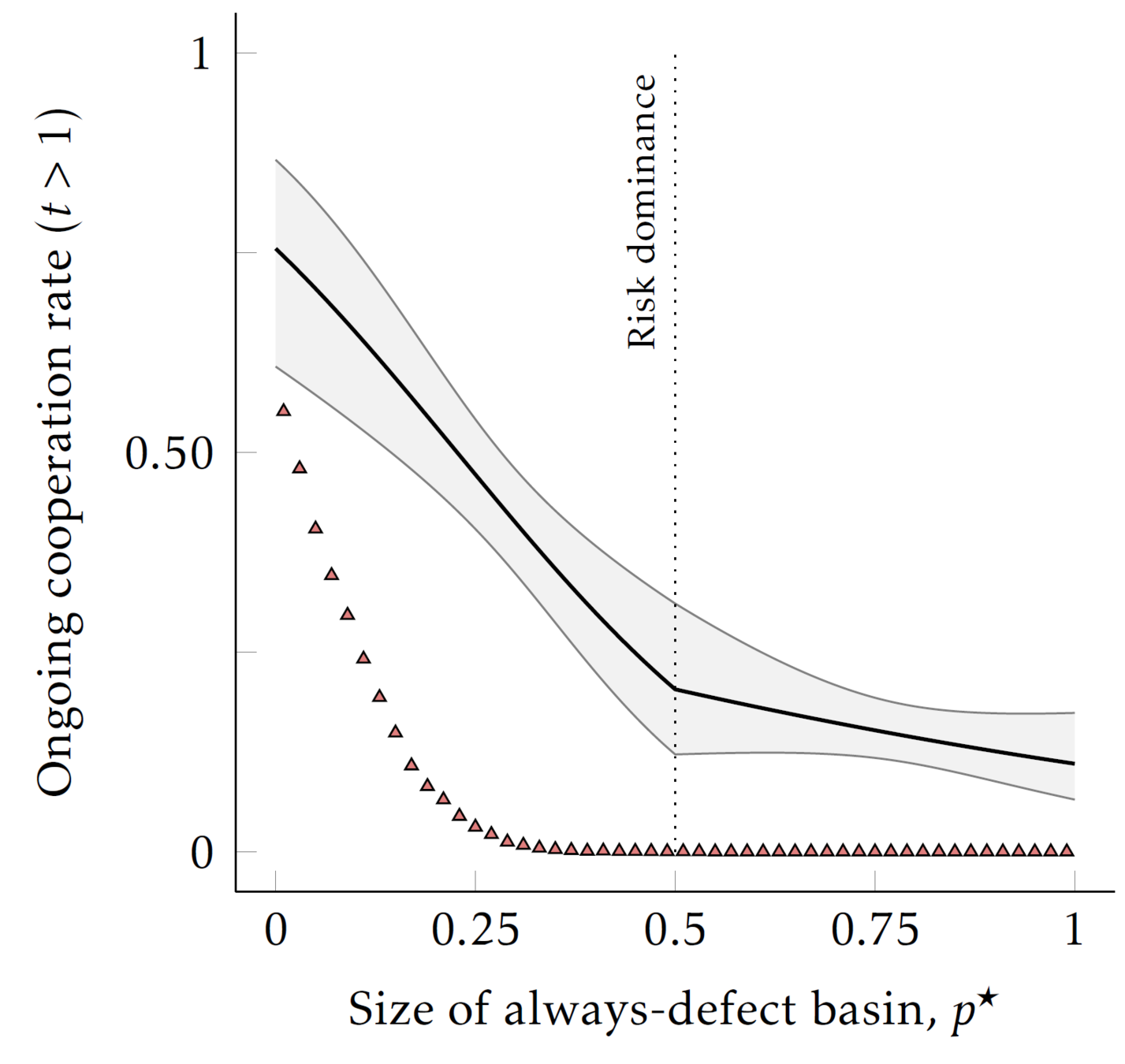

Averaging across the AI runs

Though the relationship shifts if you let the AIs learn counterfactually

Averaging across the AI runs

So within the experimental PD parameterizations we do achieve parallel results (at least on average) with AI subjects using simple updating rules:

- Human behavior "predicts" the AI behavior (at least for AIs with very simple updating rules) through the basin of attraction

- While still predictive in directional terms for the more sophisticated AIs, the basin-measure is less successful all but the most extreme parameterizations.

Going forward we think that these simple AIs can be useful in helping us understand how to extend our theories for human subjects to examine alternative environments with richer strategy spaces:

- Simple Bertrand & Cournot like settings

- Public good VCM game

And also explore where selection theories are weakest for the AIs, and use this to design experiments for humans to examine parallels.