Motivated Meritocracy:

An Experiment in the Robustness of Inequality Preferences

Brandon Williams

Experimental / Behavioral Brown Bag

February 19, 2025

Motivation

If meritocrats believe, as more and more of them are encouraged to, that their advancement comes from their own merits, they can feel they deserve whatever they can get...

as a result, general inequality has been becoming more grievous with every year that passes."

- Michael Young, 2001

Motivation: Some Facts

- 71% of the population live in country where wealth inequality has risen since 1990

- The source of inequality matters for preferences about redistribution (Young, 1958; Fong, 2001; Alesina and Angelitos, 2005; Andre, 2024)

- Some accept all forms of inequality

- Some accept inequality only if it is earned

- Some do not accept any form of inequality

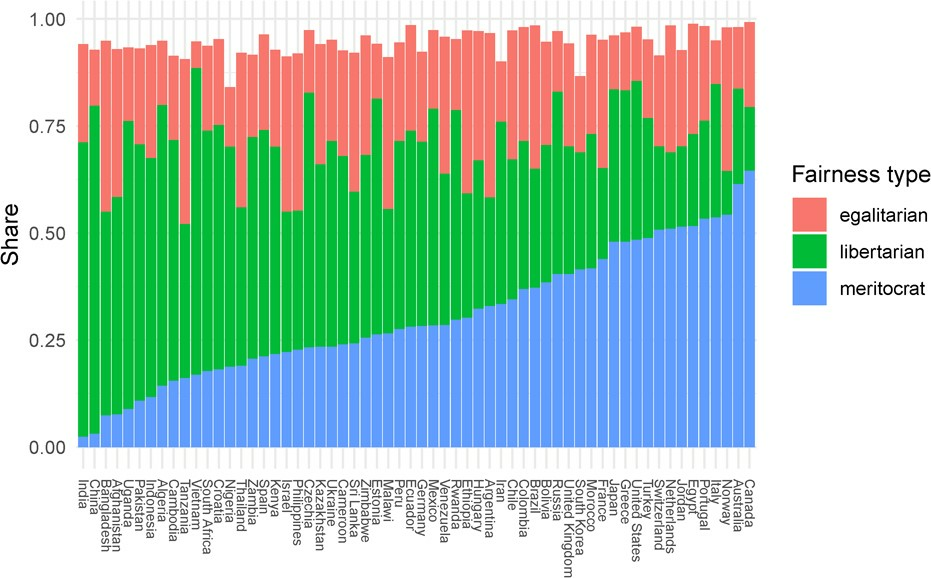

- A considerable amount of literature has worked to study the share of these types across country, political views, and gender (Cappelen et al., 2007; Almas et al., 2020; Almas et al., 2024)

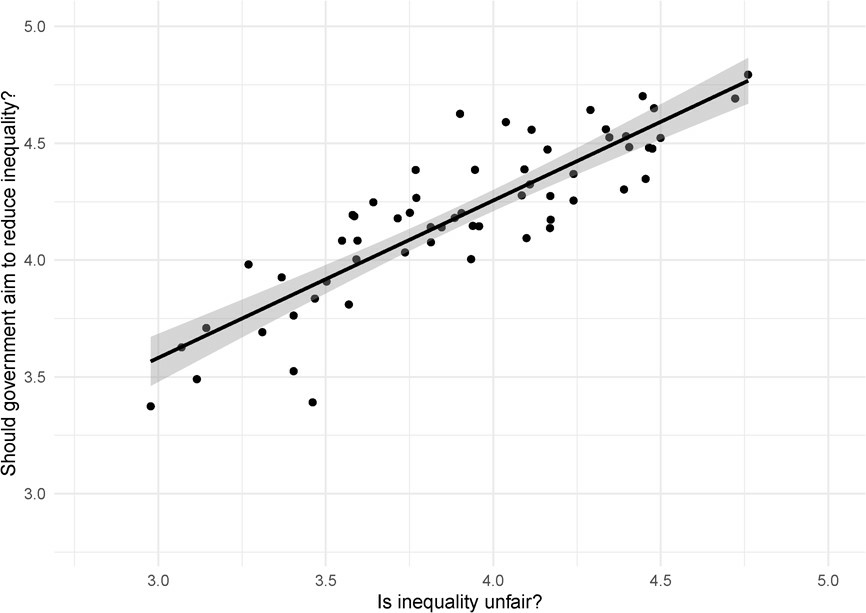

- Preferences about inequality are important because they strongly correlate with preferences about policy

Motivation: Some More Facts

- Discrimination and in-group bias are real phenomena (Becker, 1958; Tajfel et al., 1971; Chen and Li, 2009)

- Social desirability bias can lead to attenuated estimates of discriminatory intent in experiments (Kuklinski et al., 1997a, Kuklinski et al., 1997b)

- Evidence of discrimination tends to emerge more strongly when it can be hidden by other possible explanations, like list randomization techniques (e.g. Coffman et al., 2013)

- Or when observation is not apparent

- Correspondence resume studies (Bertrand and Mullainathan, 2004)

- Choice of flowers to allocate to downstream workers (Hjort, 2013)

Research Question

- How robust are inequality preferences to context and beneficiary?

- Are these views fundamental in nature, or are they exploited to justify economic outcomes that benefit one group over another?

Overall Design

- Lab-in-the-field design using a worker-spectator redistribution paradigm

- Control treatment: generic workers

- Information treatment: reveal location of workers

- Leverage stark and salient in- and out-group differences between ethnic groups in Fiji

- Measure within-group preferences about redistribution

- Measure shift in group preferences about redistribution

- Redistribution towards in-group with unfavorable allocation

- No/limited redistribution with favorable allocation

Experimental Paradigm

- From Almas et al. (2024), two types of participants:

- Workers - complete task for possible payment

- Spectators - can decide on possible redistribution of payment

- The task requires little skill but real effort (e.g. ball-catching task, counting zeros)

Experimental Paradigm

- One worker gets initial allocation according to treatment

- Luck - a fair coin determines who is paid the whole amount

- Merit - the more productive worker is paid the whole amount

$

$

$

$

$

$

Experimental Paradigm

- Spectators know the source of the allocation

- Workers are not informed of the initial distribution, but are aware a spectator will have final say

$

$

$

$

$

$

Experimental Paradigm

- Before the workers are paid, the spectator can choose to redistribute: none

$

$

$

$

$

$

Experimental Paradigm

- Before the workers are paid, the spectator can choose to redistribute: none, some,

$

$

$

$

$

$

Experimental Paradigm

- Before the workers are paid, the spectator can choose to redistribute: none, some, or all

$

$

$

$

$

$

Experimental Paradigm

- Spectators can be classified by their choices over redistribution depending on treatment

$

$

$

$

$

$

Experimental Paradigm

- Spectators can be classified by their choices over redistribution depending on treatment

$

$

$

$

$

$

Experimental Paradigm

- Spectators can be classified by their choices over redistribution depending on treatment

$

$

$

$

$

$

Experimental Paradigm

- Spectators can be classified by their choices over redistribution depending on treatment

$

$

$

$

$

$

Meritocrat*

Experimental Paradigm

- Spectators can be classified by their choices over redistribution depending on treatment

$

$

$

$

$

$

Experimental Paradigm

- Spectators can be classified by their choices over redistribution depending on treatment

$

$

$

$

$

$

Egalitarian

Experimental Paradigm

- Spectators can be classified by their choices over redistribution depending on treatment

$

$

$

$

$

$

Experimental Paradigm

- Spectators can be classified by their choices over redistribution depending on treatment

$

$

$

$

$

$

Experimental Paradigm

- Spectators can be classified by their choices over redistribution depending on treatment

$

$

$

$

$

$

Libertarian

Experimental Paradigm

- Spectators can be classified by their choices over redistribution depending on treatment

$

$

$

$

$

$

Experimental Paradigm

- Spectators can be classified by their choices over redistribution depending on treatment

$

$

$

$

$

$

Egalitarian*

Experimental Paradigm

- Spectators can be classified by their choices over redistribution depending on treatment

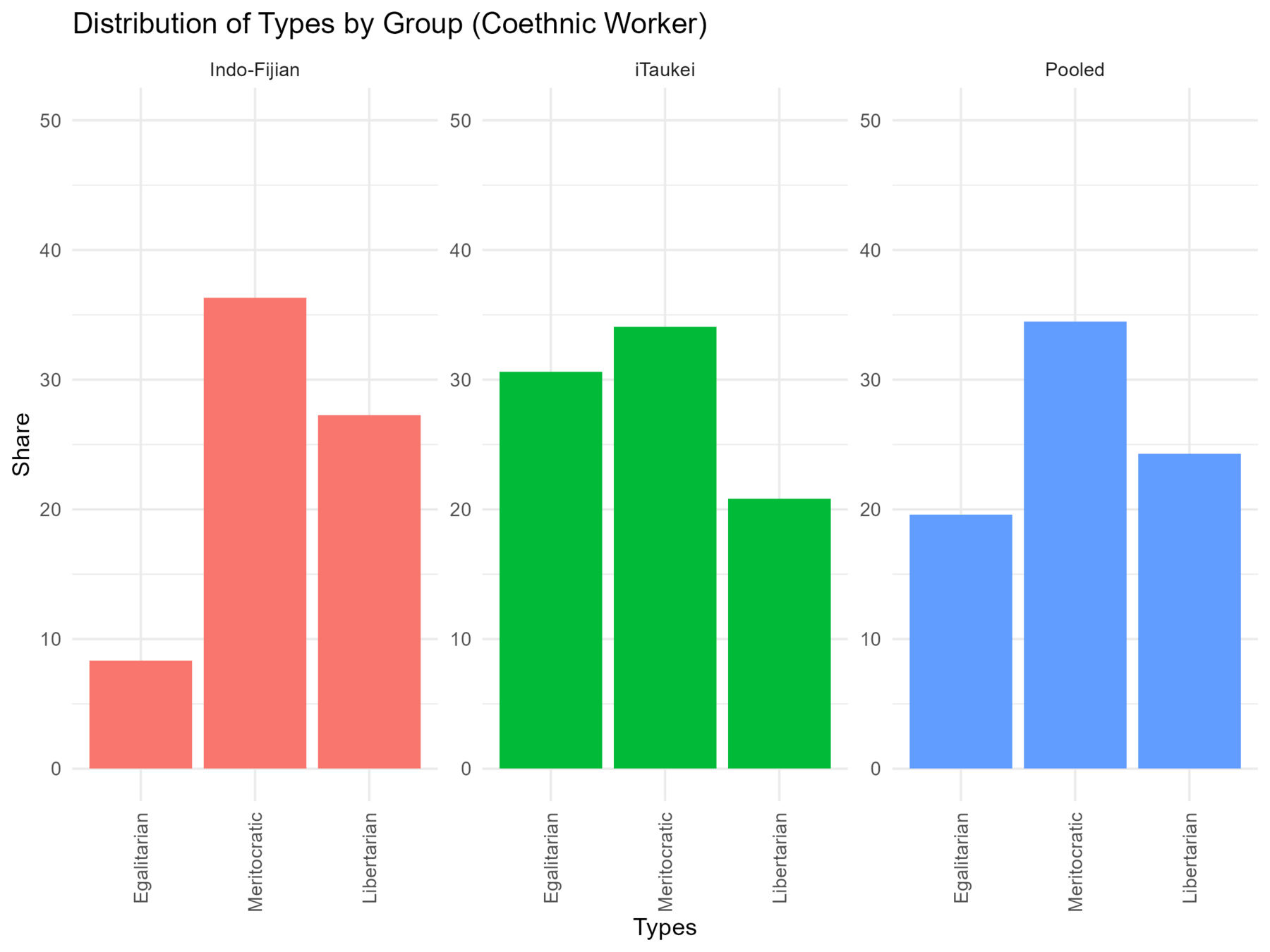

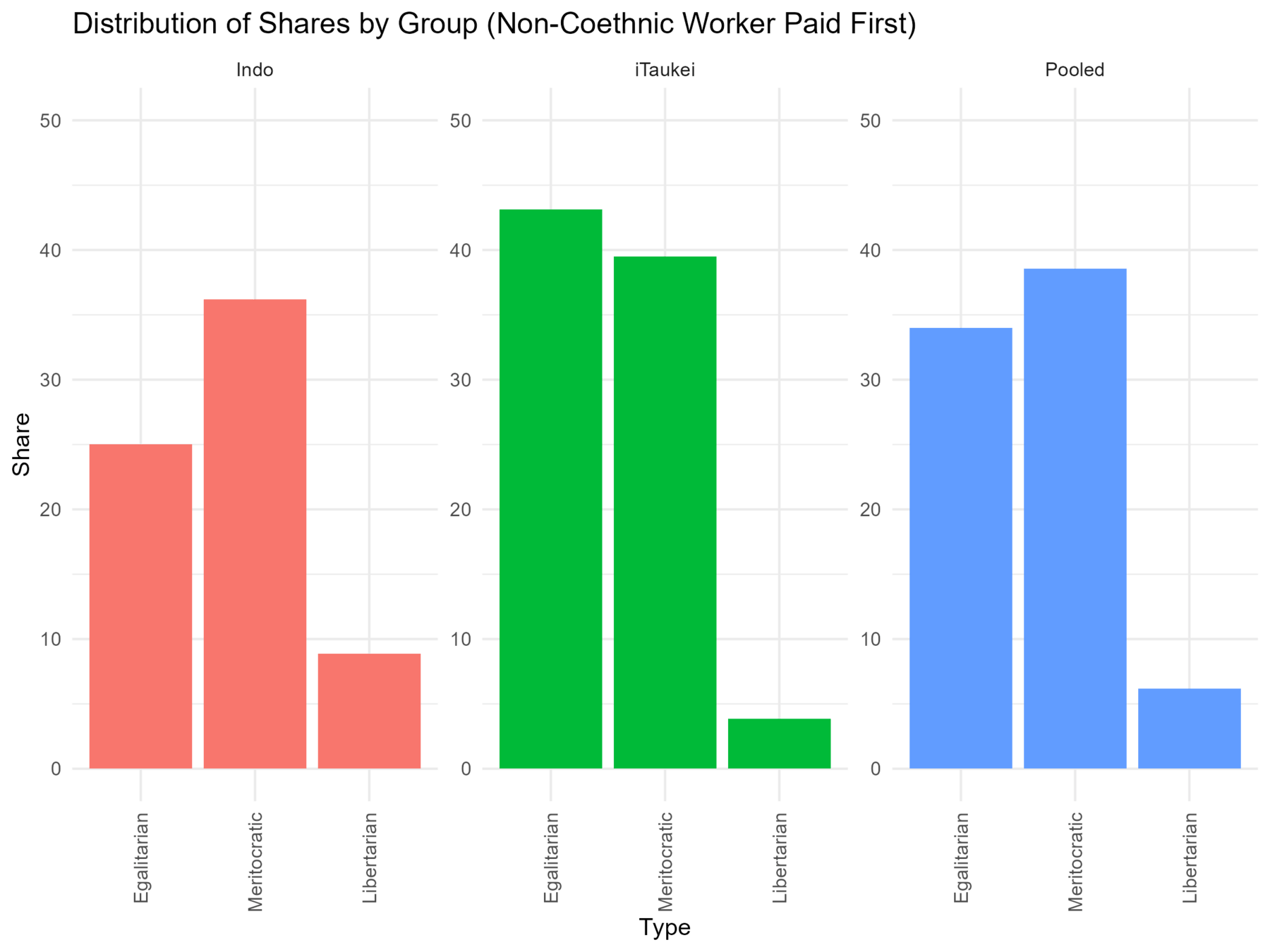

- Egalitarians - share dividing equally in the merit treatment

- Libertarians - share allocating everything to the lucky worker in the luck treatment

- Meritocrats - difference between the share of participants allocating more to the productive worker in the merit treatment and the share allocating more to the lucky worker in the luck treatment

- Other - share redistributing in other ways

Experimental Paradigm

- Equivalently, we can use the solution to the utility from the distribution between two workers:

Egalitarian

Meritocrat

Libertarian

giving us the following solutions based on preference:

Experimental Paradigm

Experimental Paradigm

- Under "blind" elicitation, spectator should always choose their personal optimal preference for inequality

- Hypothesis to be tested:

- Introducing information about workers changes the redistributive choice towards a preferred group

- Suddenly egalitarians look like meritocrats (or vice versa) when their choice benefits a certain type of worker

- "Real" preferences (in the sense of policy) are made with knowledge and inference about who will benefit from redistribution schemes

- It is vital to know if inequality preferences are robust or subject to the context of who benefits

Context: Fiji

- Island country in Melanesia north of New Zealand

- Consists of 330 islands, with about 100 inhabited, most of the population (87%) lives on one of two islands

- 1874: Fiji as a British colony

- A catastrophic measles outbreak (mortality rate of 540 out of 1000 workers) and rebellion led to limited labor force

- Beginning in 1878, the UK began bringing indentured "laborers" from India to work, eventually over 60,000

- Today, 35% of the population is Indo-Fijian, with 60% indigenous iTaukei

Context: Fiji

- Meanwhile "Fiji is for the Fijians" was adopted as official land ownership policy

- Traditional chiefs granted control over governing

- Most land could not be sold, only leased

- Today, this land agreement remains in place: 90% of land belongs to iTaukei communal land-owning units

- The majority of land is leased to farmers for agriculture

- The rents are distributed hierarchically to iTaukei communities, though until 2023 they were uniformly paid

Context: Fiji

Context: Fiji

- Since independence in 1970, "Two Fijis" is the norm

- iTaukei own land rights and receive rent payments

- Redistributive scheme within tribes

- Often iTaukei do not work the land they own, or only subsistence farm on small percentages of it

- Indo-Fijians largely comprise the cash crop production and urban business development

- Lower poverty rate (20% vs 36%)

- Generate considerable economic activity through land use

- iTaukei own land rights and receive rent payments

Context: Fiji

- Cultural differences are extremely prevalent (and salient):

- iTaukei have a stronger social identity, in-group identification, and are more collectivistic than Indo-Fijians

- iTaukei more likely to be Christians, while Indo-Fijians more likely to be Hindus or Muslims

- Geographic differences are also clearly defined:

- iTaukei: native land under traditional clan structure

- Indo-Fijian: urban centers and towns

- Political strength largely vested in iTaukei (esp. following 2000 coup), but economic strength with Indo-Fijians

Experimental Procedure

- Standard spectator game

- Each with two sub-treatments for determining types:

- Luck

- Merit

- Two experimental treatments:

- Blind treatment - no information about the workers provided to the spectator

- Information - location information about each worker, such that ethnic group of worker is readily inferred

- N = 400, balanced on iTaukei and Indo-Fijian split

- Collect their justification for making redistributive choice

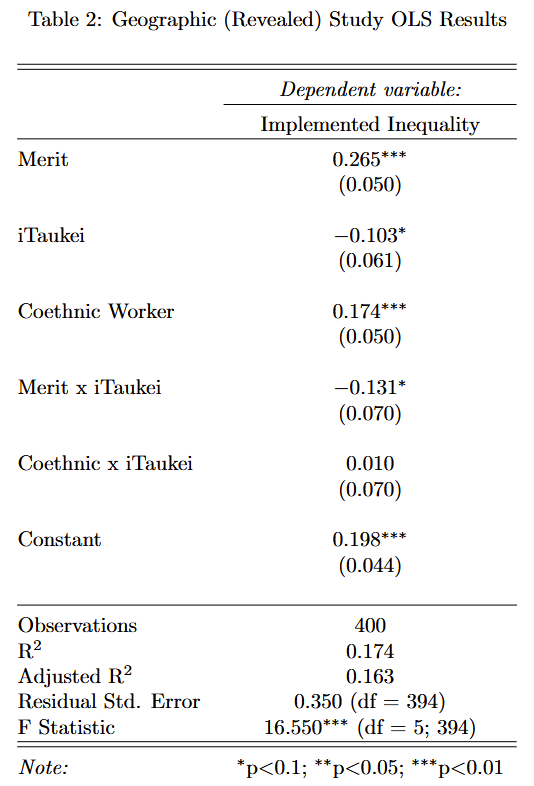

Empirical Specification

- There are two key measures from the spectator game:

- The share of each type (as defined before)

- Implemented inequality:

where the outcome is equivalent to the GINI coefficient:

Empirical Specification

- There are two key measures from the spectator game:

- The share of each type (as defined before)

- Implemented inequality:

- In the information treatment this becomes:

where the captures if the "losing" worker is in-group coethinic

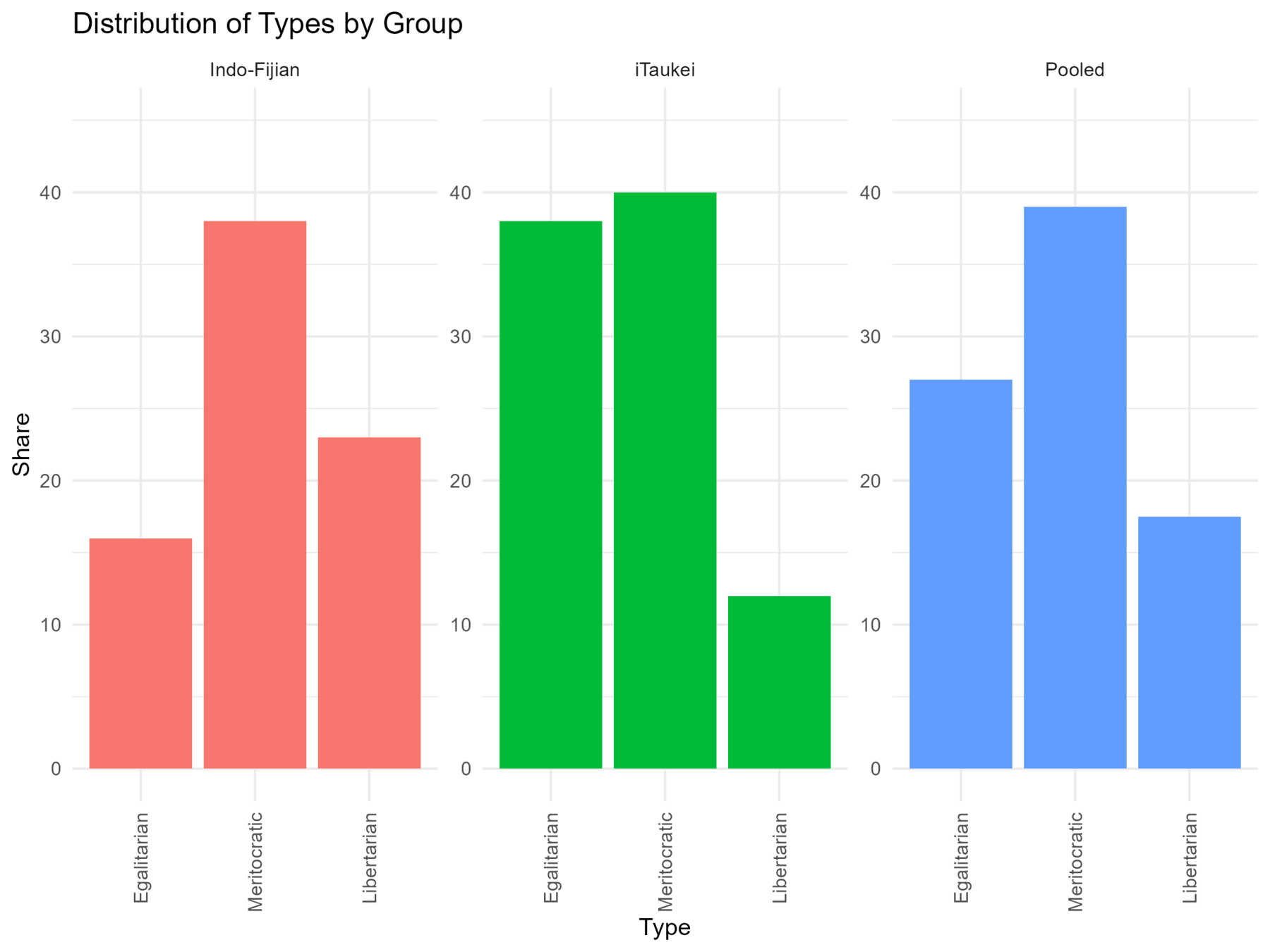

Hypothesis 1: the collectivist tradition of the iTaukei and the redistribution scheme for rents will lead to more egalitarian views

- Hypothesis 1a: there is more inequality implementation by Indo-Fijian spectators than iTaukei spectators in blind treatments

- Hypothesis 1b: there are fewer Indo-Fijian egalitarians than iTaukei egalitarians

Hypotheses

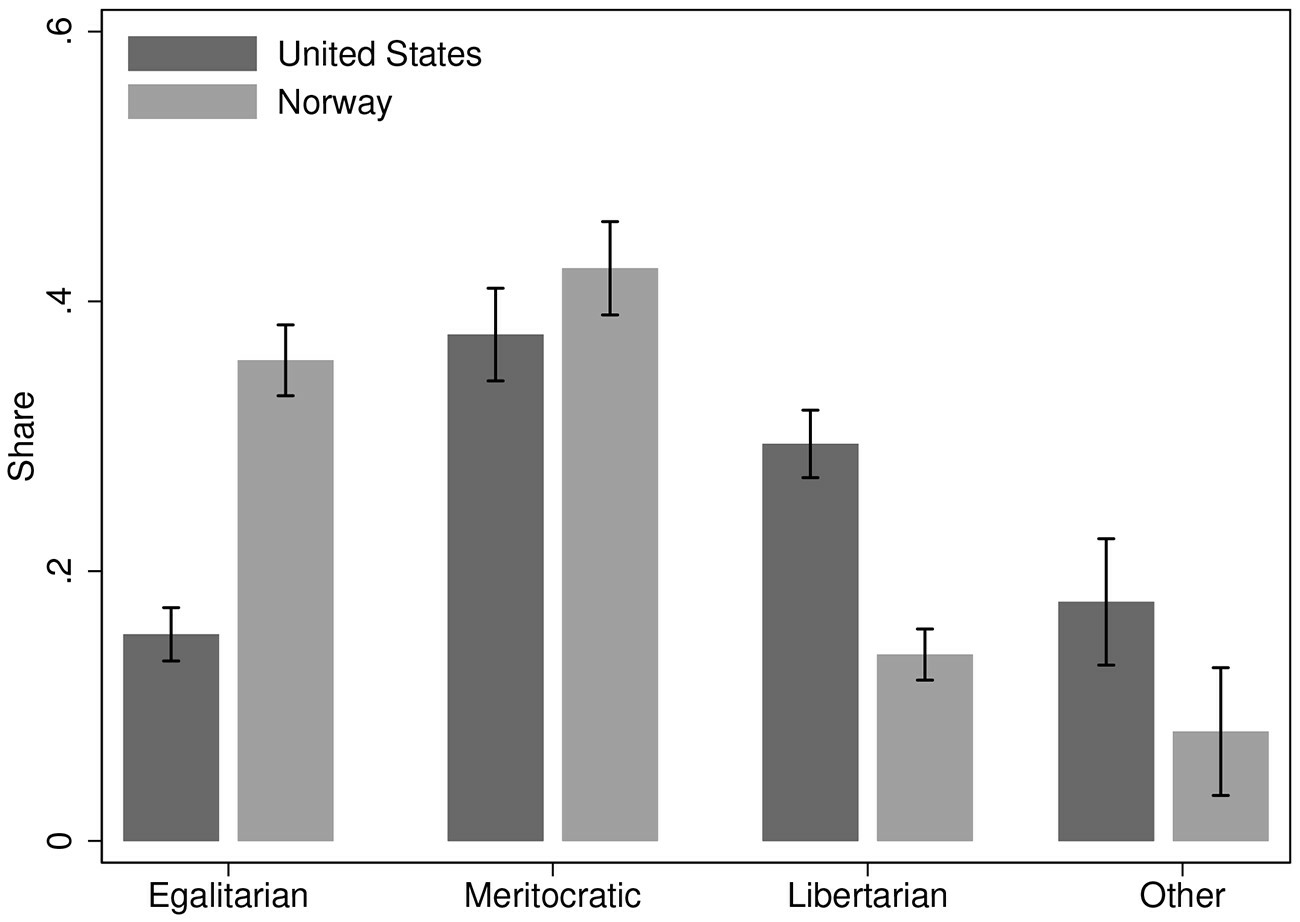

While not causal, this would provide further suggestive evidence along the lines of the differences observed between the United States and Norway

Hypothesis 2: there are systematic shifts in inequality preferences towards the in-group in information treatment

- Hypothesis 2a: when the in-group benefits from the initial payment scheme, fewer people choose to redistribute

- Hypothesis 2b: when the in-group does not benefit from the initial payment scheme, more people choose to redistribute

- Hypothesis 2c: conditioning on in-group performance, the distribution of types is not the same

Hypotheses

Given blind versus information conditioning on in-group performing worse (merit treatment) or being unlucky (luck):

Additional Things I'm Thinking About

- Adding a treatment with specific details about the workers to test direct pathway to in-group preference

- Adding a treatment with a non-Fijian worker to determine the role of geographic distance

- Developing a meaningful / useful task for the workers, and determining logistically how to pay the workers

- Repeating the task within-subject to determine if spectators attenuate the bias shift in order to stay consistent

- For example, going from blind in first rounds to geographic in later rounds

- Or, seeing the immediate beneficiaries of payment switch from in-group to out-group

Conclusion

- Understanding the stability of inequality preferences is important for a cohesive policy agenda

- Redistributive policies can be an effective way to favor a group under veiled discrimination

- Experimental procedure that uses an established paradigm and introduces an in- and out-group dimension with testable implications

- Fiji offers a unique context in which to study:

- History of different groups enjoying differing levels of political and economic power

- Clear inference about worker type can be drawn with little exact revealed details

Motivated Meritocracy

Thank you!

Preferences about inequality and policy

Types Around the World

Norway and the US

A Model of (Context-Dependent) Inequality

The spectator seeks to maximize their utility from the distribution of resources:

Weight to worker 1

Allocation to worker 1

Strength of inequality preferences

Inequality preferences

A Model of (Context-Dependent) Inequality

The spectator seeks to maximize their utility from the distribution of resources:

Since the overall pot is fixed, we can rewrite this as:

A Model of (Context-Dependent) Inequality

The spectator seeks to maximize their utility from the distribution of resources:

A Model of (Context-Dependent) Inequality

The spectator seeks to maximize their utility from the distribution of resources:

Difference in weights on two types of workers

Discrimination

A Model of (Context-Dependent) Inequality

The spectator seeks to maximize their utility from the distribution of resources:

A Model of (Context-Dependent) Inequality

The spectator seeks to maximize their utility from the distribution of resources:

If we assume there is no benefit from giving to a particular worker:

A Model of (Context-Dependent) Inequality

The spectator seeks to maximize their utility from the distribution of resources:

If we assume there is no benefit from giving to a particular worker:

This is the traditional model, solved by FOC:

A Model of (Context-Dependent) Inequality

This is the traditional model, solved by FOC:

We can classify people by type given their redistribution choice:

Egalitarian

Meritocrat

Libertarian

A Model of (Context-Dependent) Inequality

The spectator seeks to maximize their utility from the distribution of resources:

If we allow for some preference over who gets redistribution:

Which yields FOC:

A Model of (Context-Dependent) Inequality

Which yields FOC:

Then only allocate according to inequality preferences if spectator really cares about inequality preferences

Otherwise, bias towards one participant causes misrepresentation as a different type, which disguises the discrimination

A Model of (Context-Dependent) Inequality

We need not allow for direct discrimination by providing the identity of the workers; it can be probabilistic:

Potentially, the probability attenuates the bias based on inference.

However, it behaviorally provides more "cover" for discrimination under an inequality preference

A Model of (Context-Dependent) Inequality

- Key takeaways:

- Under "blind" elicitations, spectator should always choose their personal optimal preference for inequality

- Introducing any information about workers may bias the redistributive choice

- Suddenly egalitarians look like meritocrats (or vice versa) when their choice benefits a certain type of worker

- My argument henceforth

- "Real" preferences (in the sense of policy) are made with knowledge and inference about who will benefit from redistribution schemes

- It is vital to know if inequality preferences are stable or subject to the context of who benefits

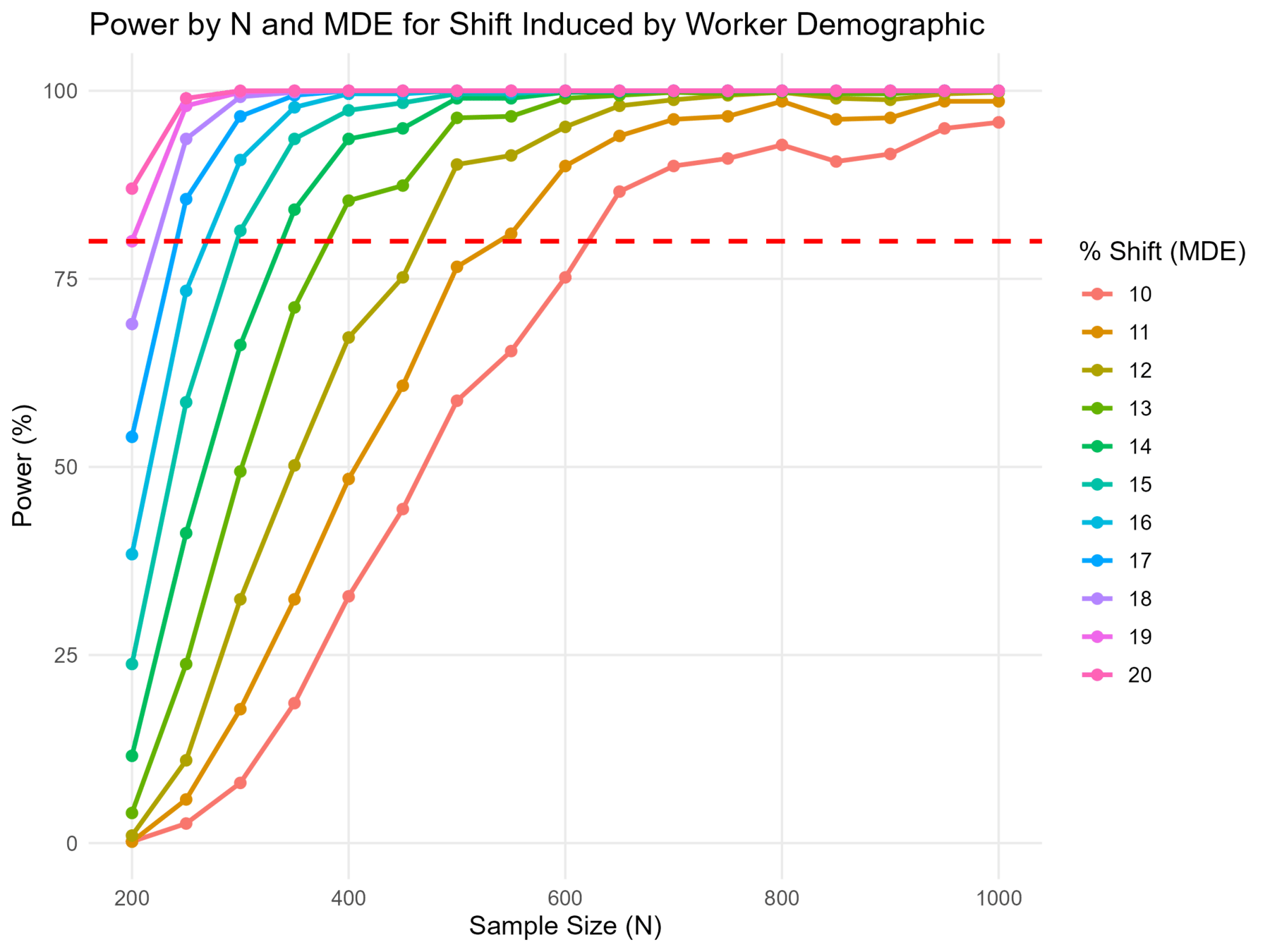

Power Simulation

Simulated Data

Simulated Data

Simulated Data

Simulated Data