Preferences and Utility

Christopher Makler

Stanford University Department of Economics

Econ 50: Lecture 3

Today's Agenda

Part 1: Modeling Preferences with Utility Functions

Part 2: Using Functional Forms to Describe Economic Phenomena

Quantifying Happiness

Indifference curves as Level Sets

Positive Monotonic Transformations

Perfect Substitutes

Perfect Complements

Cobb-Douglas

Quasilinear

Satiation Point

Concave

Quantifying Happiness

How do I love thee? Let me count the ways.

I love thee to the depth and breadth and height

My soul can reach, when feeling out of sight

For the ends of Being and ideal Grace.

I love thee to the level of everyday’s

Most quiet need, by sun and candlelight.

I love thee freely, as men strive for Right;

I love thee purely, as they turn from Praise.

I love thee with the passion put to use

In my old griefs, and with my childhood’s faith.

I love thee with a love I seemed to lose

With my lost saints,—I love thee with the breath,

Smiles, tears, of all my life!—and, if God choose,

I shall but love thee better after death.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning

Sonnets from the Portugese 43

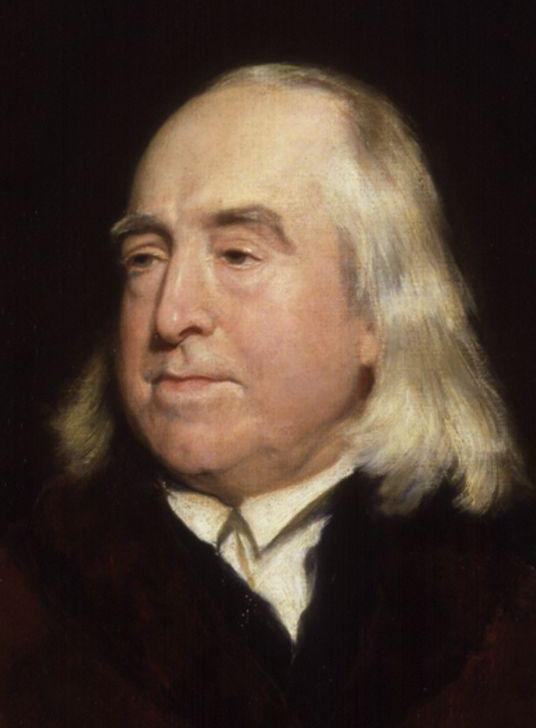

18th/19th Centuries: Utilitarianism

the greatest happiness of the greatest number

is the foundation of morals and legislation.

Jeremy Bentham

the utilitarian standard...

is not the agent's own greatest happiness,

but the greatest amount of happiness, altogether.

John Stuart Mill

Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation (1789)

Utilitarianism (1861)

Preferences: Ordinal Ranking of Options

Given a choice between option A and option B, an agent might have different preferences:

The agent strictly prefers A to B.

The agent strictly disprefers A to B.

The agent weakly prefers A to B.

The agent weakly disprefers A to B.

The agent is indifferent between A and B.

Preference Axioms

Complete

Transitive

Any two options can be compared.

If \(A\) is preferred to \(B\), and \(B\) is preferred to \(C\),

then \(A\) is preferred to \(C\).

Together, these assumptions mean that we can rank

all possible choices in a coherent way.

Representing Preferences with a Utility Function

"A is strictly preferred to B"

Words

Preferences

Utility

"A is weakly preferred to B"

"A is indifferent to B"

"A is weakly dispreferred to B"

"A is strictly dispreferred to B"

Suppose the "utility function"

assigns a real number (in "utils")

to every possible consumption bundle

We get completeness because any two numbers can be compared,

and we get transitivity because that's a property of the operator ">"

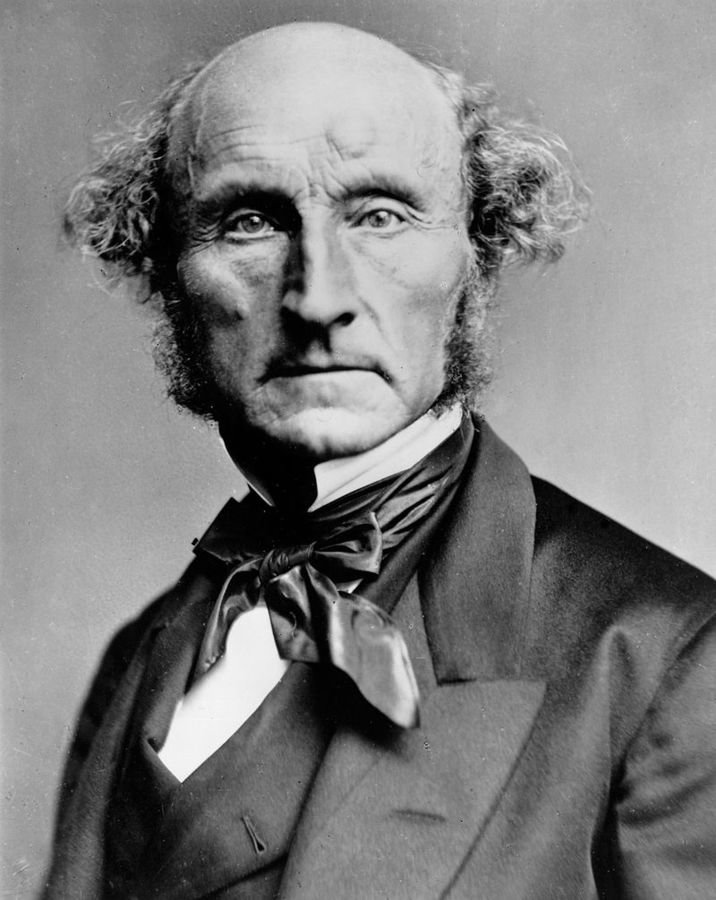

An indifference curve is a set of all bundles between which a consumer is indifferent.

If a consumer is indifferent between two bundles (A ~ B), then \(u(a_1,a_2) = u(b_1,b_2)\)

Therefore, an indifference curve is a set of all consumption bundles which are assigned the same number of "utils" by the function \(u(x_1,x_2)\)

Likewise, set of bundles preferred to some bundle A is the a set of all consumption bundles which are assigned a greater number of "utils" by \(u(x_1,x_2)\)

Example: draw the indifference curve for \(u(x_1,x_2) = \frac{1}{2}x_1x_2^2\) passing through (4,6).

Step 1: Evaluate \(u(x_1,x_2)\) at the point

Step 2: Set \(u(x_1,x_2)\) equal to that value.

Step 4: Plug in various values of \(x_1\) and plot!

\(u(4,6) = \frac{1}{2}\times 4 \times 6^2 = 72\)

\(\frac{1}{2}x_1x_2^2 = 72\)

\(x_2^2 = \frac{144}{x}\)

\(x_2 = \frac{12}{\sqrt x_1}\)

How to Draw an Indifference Curve through a Point: Method I

Step 3: Solve for \(x_2\).

How would this have been different if the utility function were \(u(x_1,x_2) = \sqrt{x_1} \times x_2\)?

\(u(4,6) =\sqrt{4} \times 6 = 12\)

\(\sqrt{x_1} \times x_2 = 12\)

\(x_2 = \frac{12}{\sqrt x_1}\)

Marginal Utility

Econ 1: "The additional utility you get from consuming another unit of the good"

Now that we know calculus, it's much easier:

Approximately much additional utility do you get from increasing your consumption of good 1 by 3 units?

What are the units of marginal utility?

Marginal Rate of Substitution

From last time: "The amount of good 2 you would give up in order to get another unit of good 1 and be no better or worse off"

How much utility do you lose when you give up \(dx_2\) units of good 2?

How much utility do you gain when you get \(dx_1\) units of good 1?

If you gain the same amount of utility from good 1 as you lost from good 2, can you express the MRS in terms of \(dx_1\) and \(dx_2\)?

A

B

Example: draw the indifference curve for \(u(x_1,x_2) = \frac{1}{2}x_1x_2^2\) passing through (4,6).

Step 1: Derive \(MRS(x_1,x_2)\). Determine its characteristics: is it smoothly decreasing? Constant?

Step 2: Evaluate \(MRS(x_1,x_2)\) at the point.

Step 4: Sketch the right shape of the curve, so that it's tangent to the line at the point.

How to Draw an Indifference Curve through a Point: Method II

Step 3: Draw a line passing through the point with slope \(-MRS(x_1,x_2)\)

How would this have been different if the utility function were \(u(x_1,x_2) = \sqrt{x_1} \times x_2\)?

This is continuously strictly decreasing in \(x_1\) and continuously strictly increasing in \(x_2\),

so the function is smooth and strictly convex and has the "normal" shape.

Do we have to take the

number of "utils" seriously?

Plot "utility" as a function.

"Marginal utility" is its derivative.

What could go wrong?

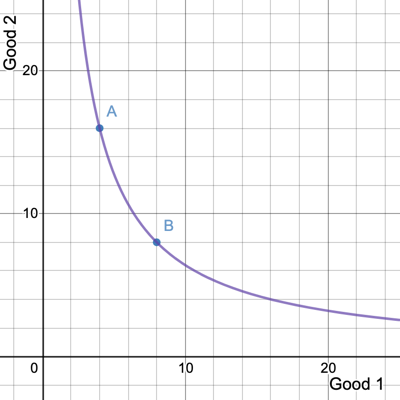

BS METER

What are the units? "Utils?"

From XKCD:

Just like the "volume" on an amp, "utils" are an arbitrary scale...saying you're "11" happy from a bundle doesn't mean anything!

All we want to use utility functions for

is to describe preference orderings.

It doesn't matter that “utils" are nonsense.

As long as the utility function generates the correct indifference map,

it doesn't matter what the level of utility at each indifference curve is.

Transforming Utility Functions

Applying a positive monotonic transformation to a utility function doesn't affect

the way it ranks bundles.

Example: \(\hat u(x_1,x_2) = 2u(x_1,x_2)\)

Transformations and the MRS

Applying a positive monotonic transformation to a utility function doesn't affect

its MRS at any bundle (and therefore generates the same indifference map).

Example: \(\hat u(x_1,x_2) = 2u(x_1,x_2)\)

Transformations and the MRS

Applying a positive monotonic transformation to a utility function doesn't affect

its MRS at any bundle (and therefore generates the same indifference map).

Example: \(\hat u(x_1,x_2) = \ln(u(x_1,x_2))\)

Normalizing Utility Functions

One reason to transform a utility function is to normalize it.

This allows us to describe preferences using fewer parameters.

[ multiply by \({1 \over a + b}\) ]

[ let \(\alpha = {a \over a + b}\) ]

Desirable Properties of Preferences

We've asserted that all (rational) preferences are complete and transitive.

There are some additional properties which are true of some preferences:

- Monotonicity

- Convexity

- Continuity

- Smoothness

Monotonic Preferences: “More is Better"

Nonmonotonic Preferences and Satiation

Some goods provide positive marginal utility only up to a point, beyond which consuming more of them actually decreases your utility.

Strict vs. Weak Monotonicity

Strict monotonicity: any increase in any good strictly increases utility (\(MU > 0\) for all goods)

Weak monotonicity: no increase in any good will strictly decrease utility (\(MU \ge 0\) for all goods)

Example: Pfizer's COVID-19 vaccine has a dose of 0.3mL, Moderna's has a dose of 0.5mL

Goods vs. Bads

Convex Preferences: “Variety is Better"

Math background: "Convex combinations"

Convex Preferences: “Variety is Better"

Take any two bundles, \(A\) and \(B\), between which you are indifferent.

Would you rather have a convex combination of those two bundles,

than have either of those bundles themselves?

If you would always answer yes, your preferences are convex.

Concave Preferences: “Variety is Worse"

Take any two bundles, \(A\) and \(B\), between which you are indifferent.

Would you rather have a convex combination of those two bundles,

than have either of those bundles themselves?

If you would always answer no, your preferences are convex.

Common Mistakes about Convexity

1. Convexity does not imply you always want equal numbers of things.

2. It's preferences which are convex, not the utility function.

Other Desirable Properties

Continuous: utility functions don't have "jumps"

Smooth: marginal utilities don't have "jumps"

Counter-example: vaccine dose example

Counter-example: Leontief/Perfect Complements utility function

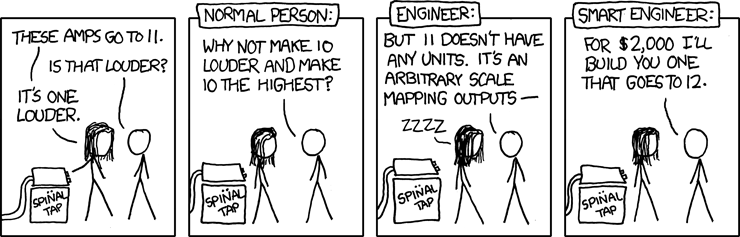

Well-Behaved Preferences

If preferences are strictly monotonic, strictly convex, continuous, and smooth, then:

Indifference curves are smooth, downward-sloping, and bowed in toward the origin

The MRS is diminishing as you move down and to the right along an indifference curve

Good 1 \((x_1)\)

Good 2 \((x_2)\)

"Law of Diminishing MRS"

Summary of Part I

Part I: properties of preferences,

and how preferences can be represented by utility functions.

Part II: see examples of utility functions,

and examine how different functional forms

can be used to model different kinds of preferences.

Take the time to understand this material well.

It's foundational for many, many economic models.