Uncertainty and Risk

Christopher Makler

Stanford University Department of Economics

Econ 51: Lecture 4

Uncertainty and Risk

Lecture 4

Up to now: no uncertainty about what is going to happen in the world.

In the real world: lots of uncertainty!

We'll model this by thinking about preferences over consumption lotteries in which you consume different amounts in different states of the world.

We're just going to think about preferences, not budget constraints.

Today's Agenda

Part 1: Preferences over Risk

Part 2: Market Implications

[worked example]

Lotteries

Expected Utility

Certainty Equivalence and Risk Premium

Insurance

Risky Assets

Option A

Option B

I flip a coin.

Heads, you get 1 extra homework point.

Tails, you get 9 extra homework points.

I give you 5 extra homework points.

pollev.com/chrismakler

Heads, you get 5 extra homework points.

Tails, you get 5 extra homework points.

Option A

Option B

I flip a coin.

Heads, you get 1 extra homework point.

Tails, you get 9 extra homework points.

I give you 5 extra homework points.

Heads, you get 5 extra homework points.

Tails, you get 5 extra homework points.

Expected Utility

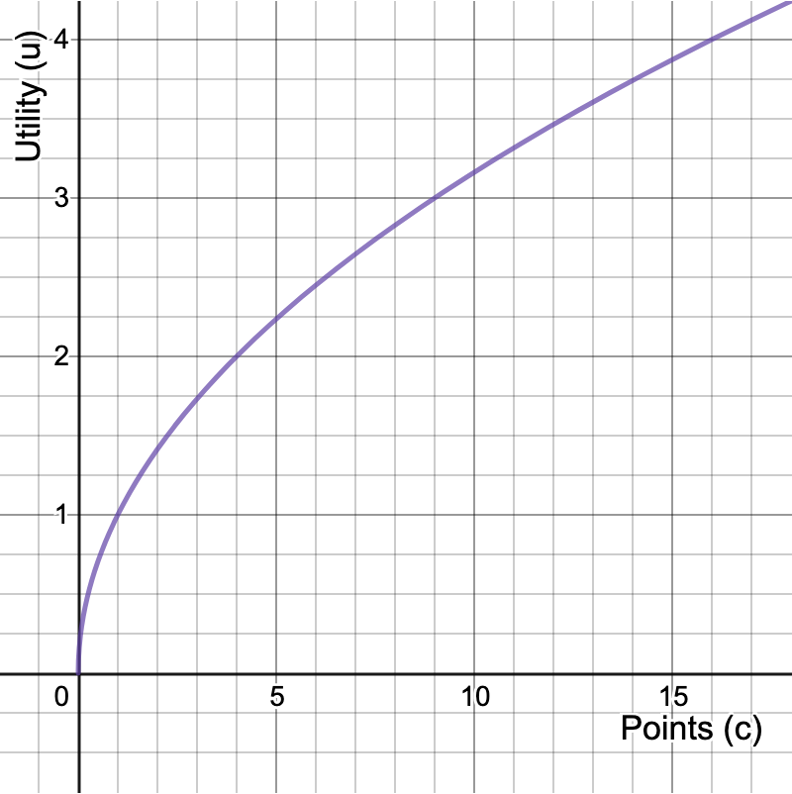

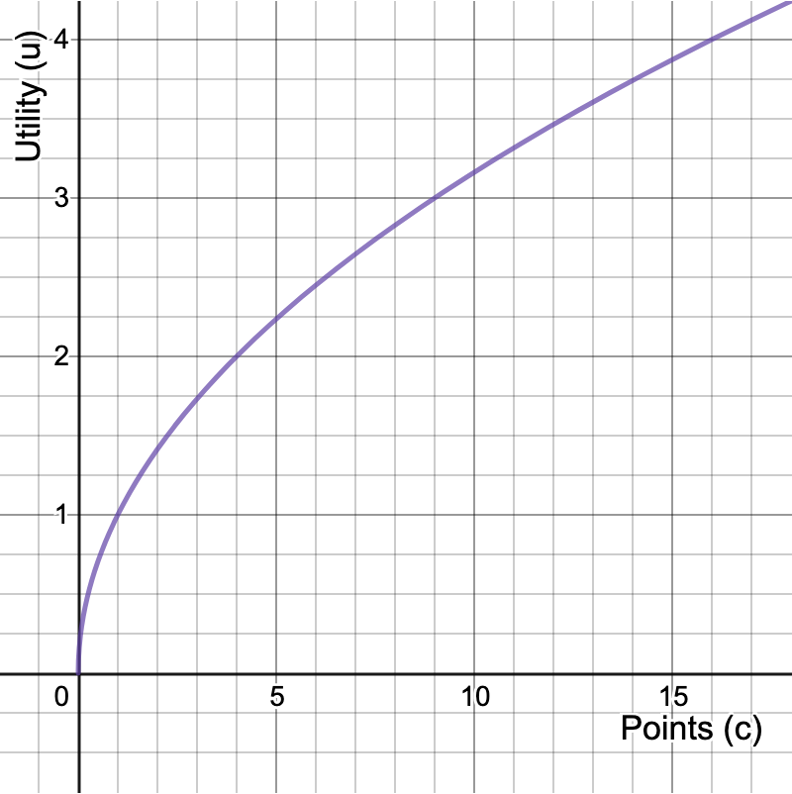

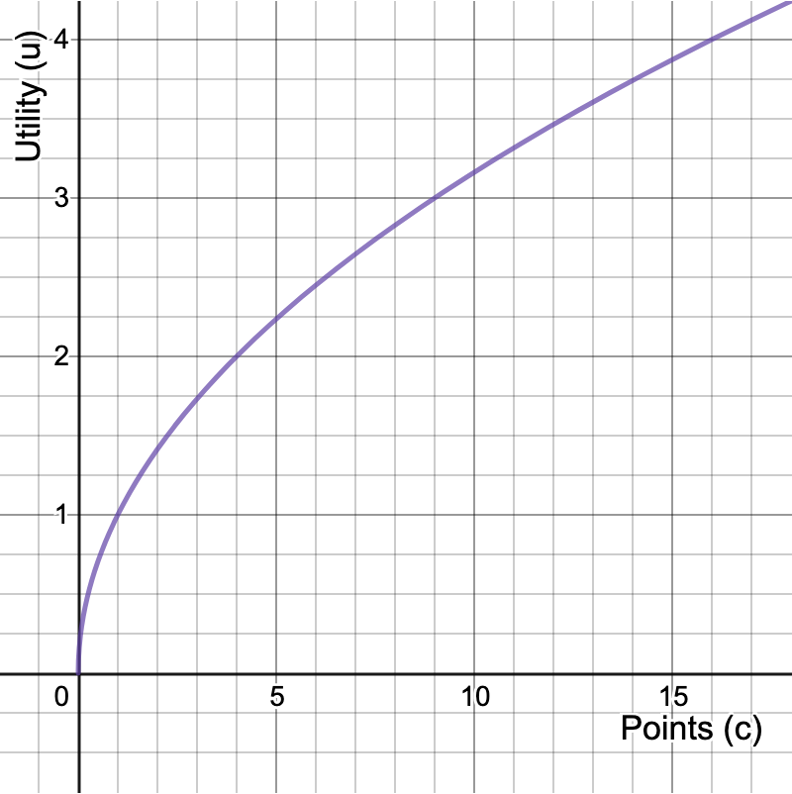

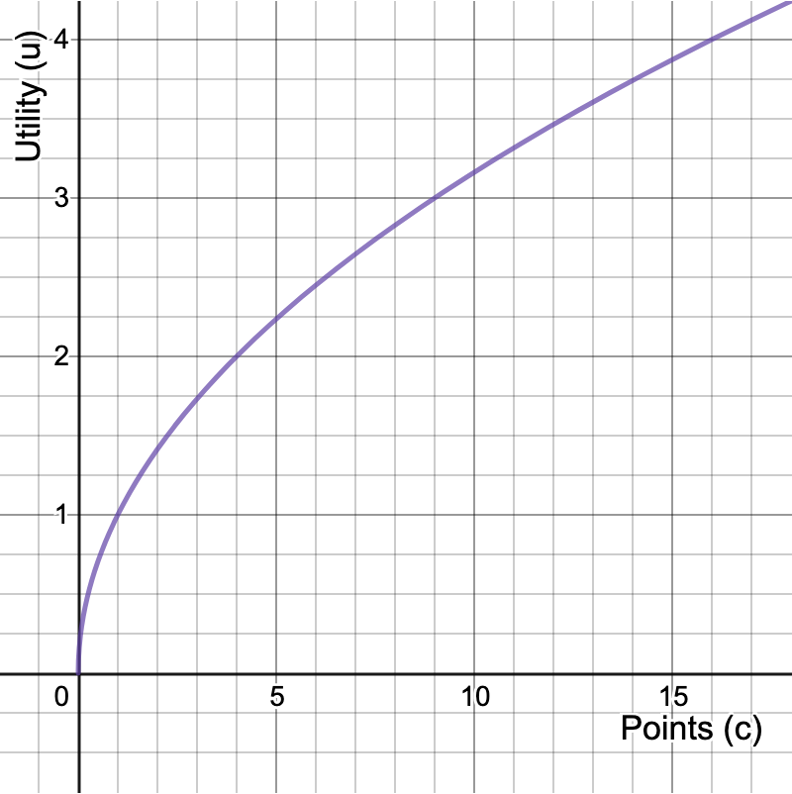

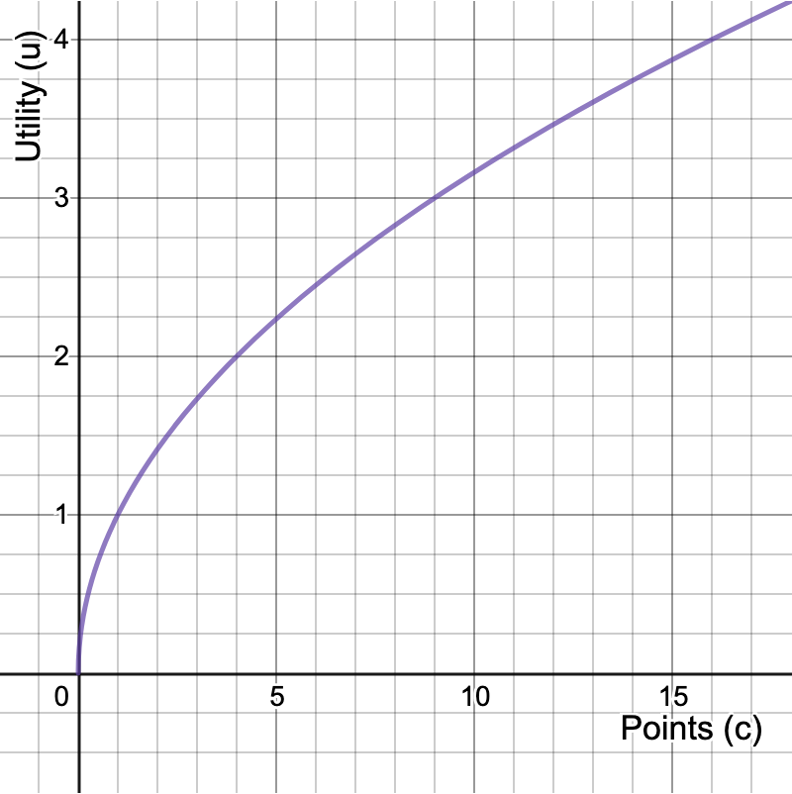

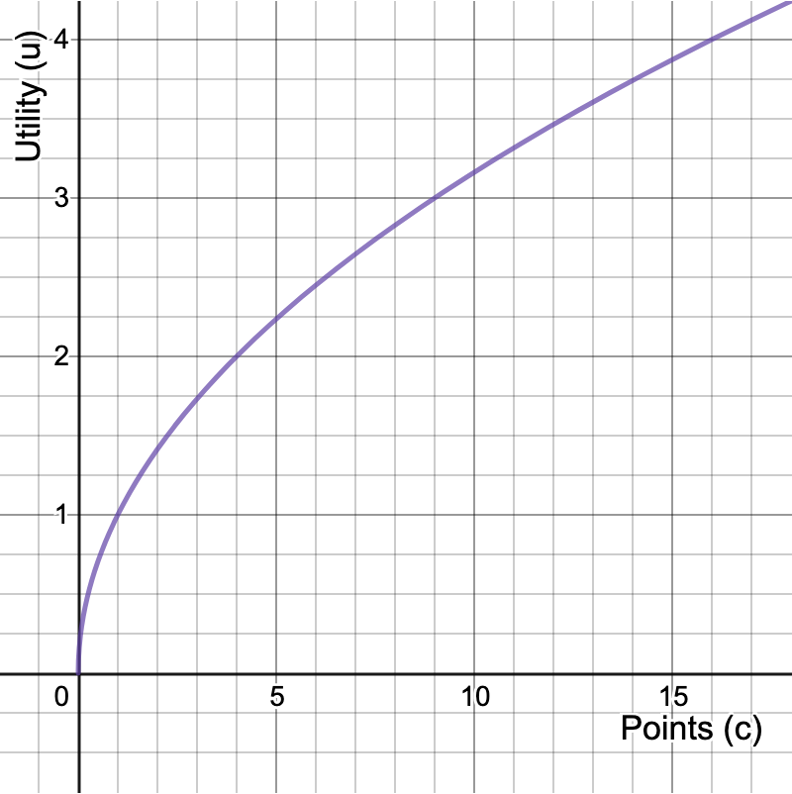

Suppose your utility from points is given by

Expected value of the homework points (c) is:

Expected value of your utility (u) is:

Risk Aversion

Expected value of the homework points (c) is:

Utility from expected points is:

Expected value of your utility (u) is:

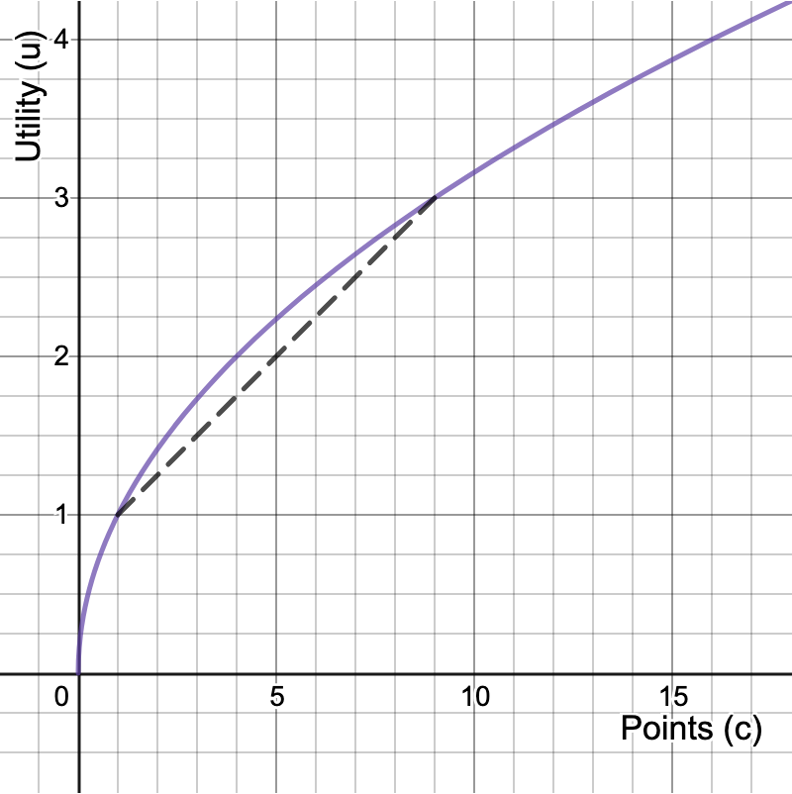

Because the utility from having 5 points for sure is higher than the expected utility of the lottery, this person would be risk averse.

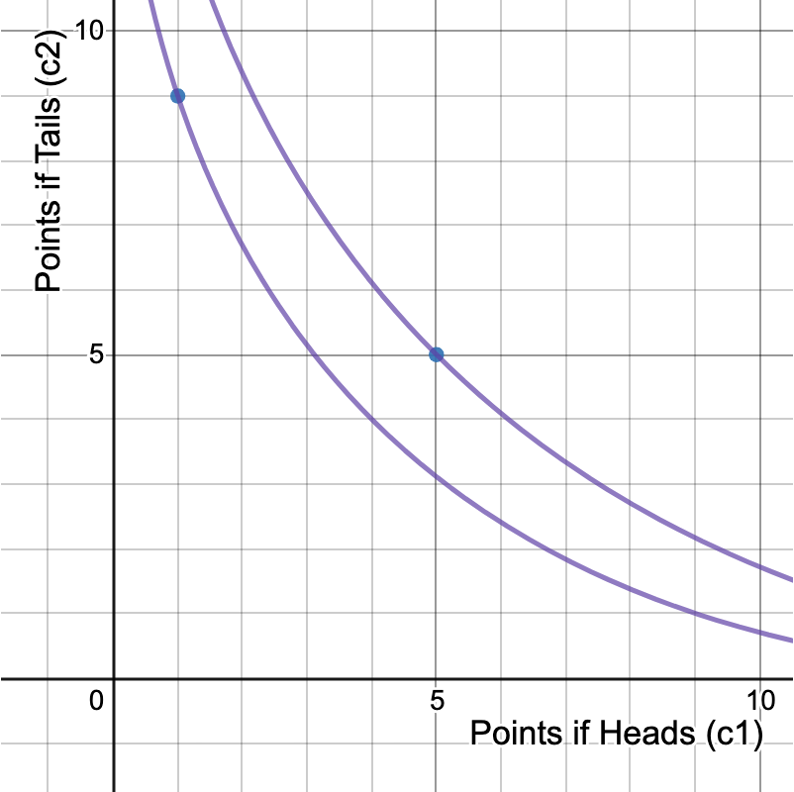

Utility from expected points:

Expected utility (u):

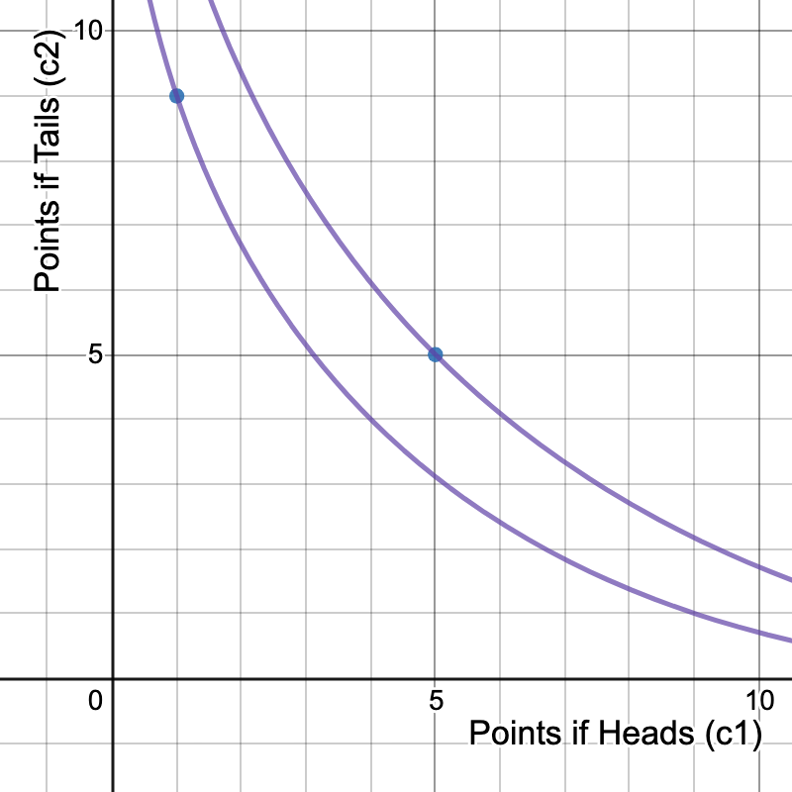

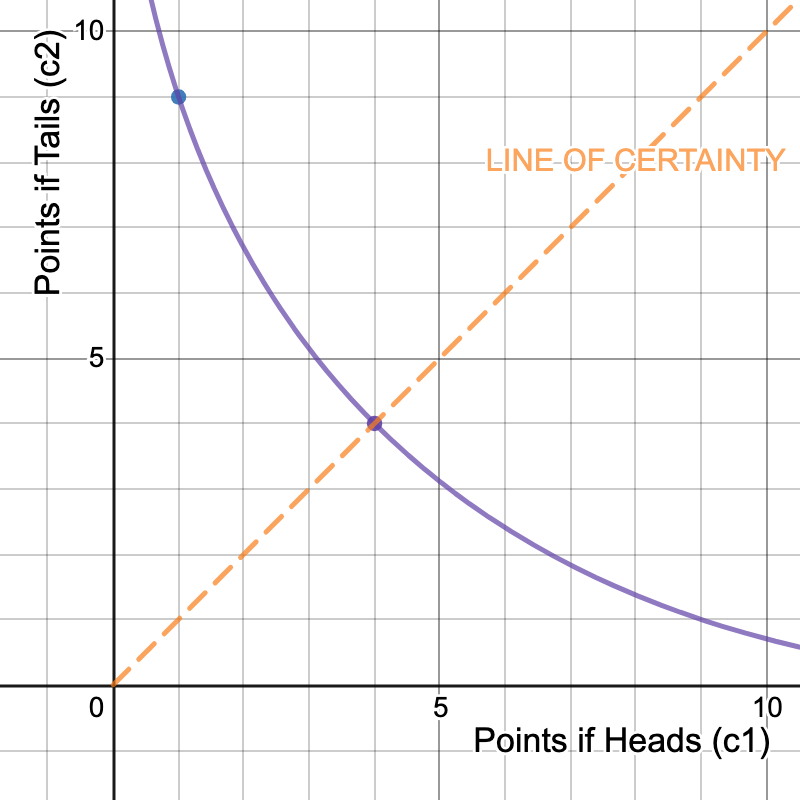

Indifference curve for 2 utils

Indifference curve for

\(\sqrt{5}\) utils

Option A

Option B

I flip a coin.

Heads, you get 1 extra homework point.

Tails, you get 9 extra homework points.

I give you 4 extra homework points.

pollev.com/chrismakler

Heads, you get 4 extra homework points.

Tails, you get 4 extra homework points.

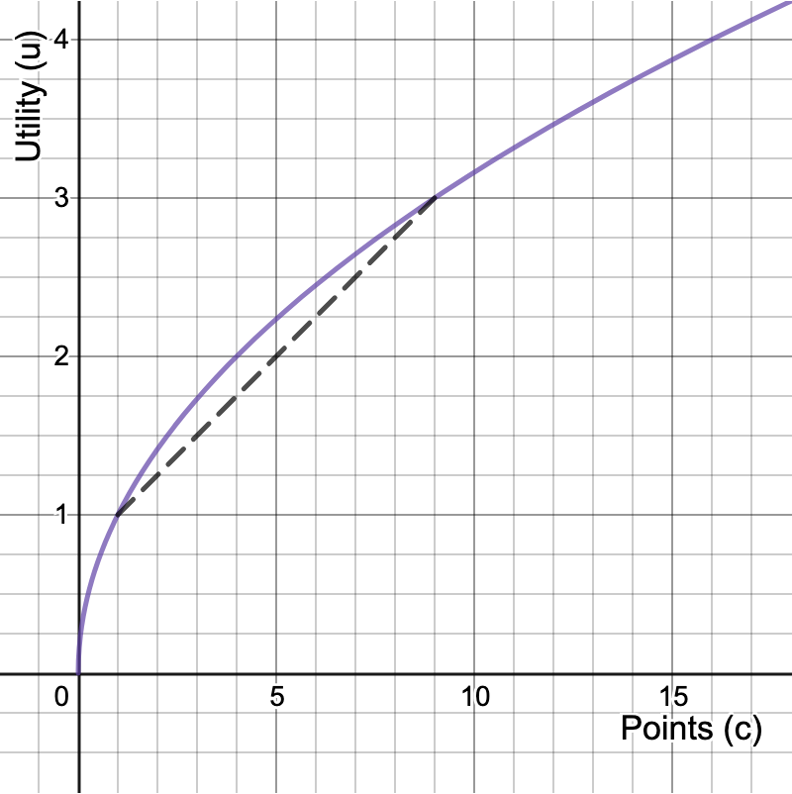

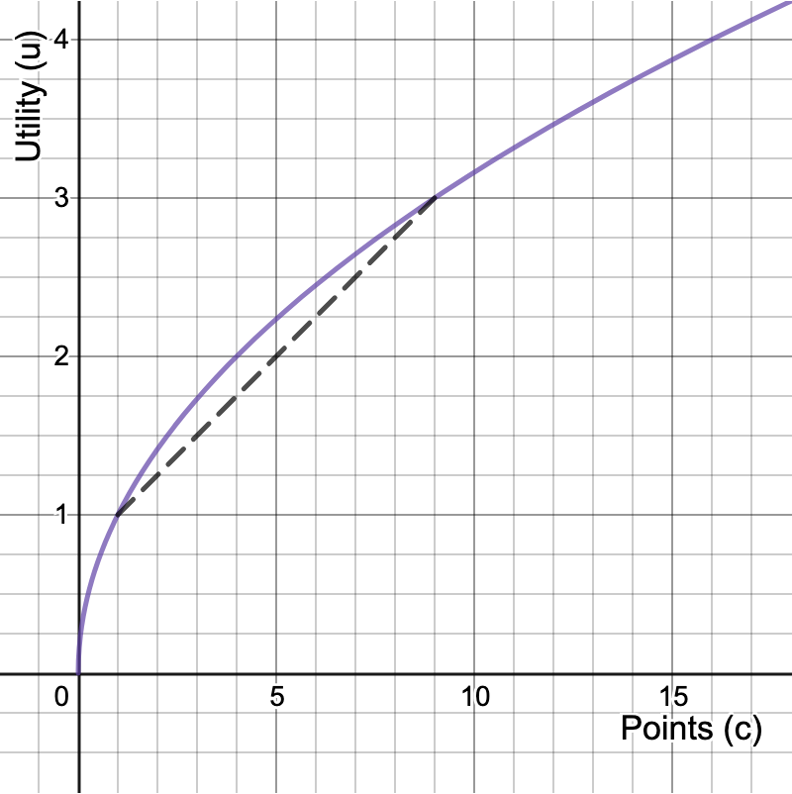

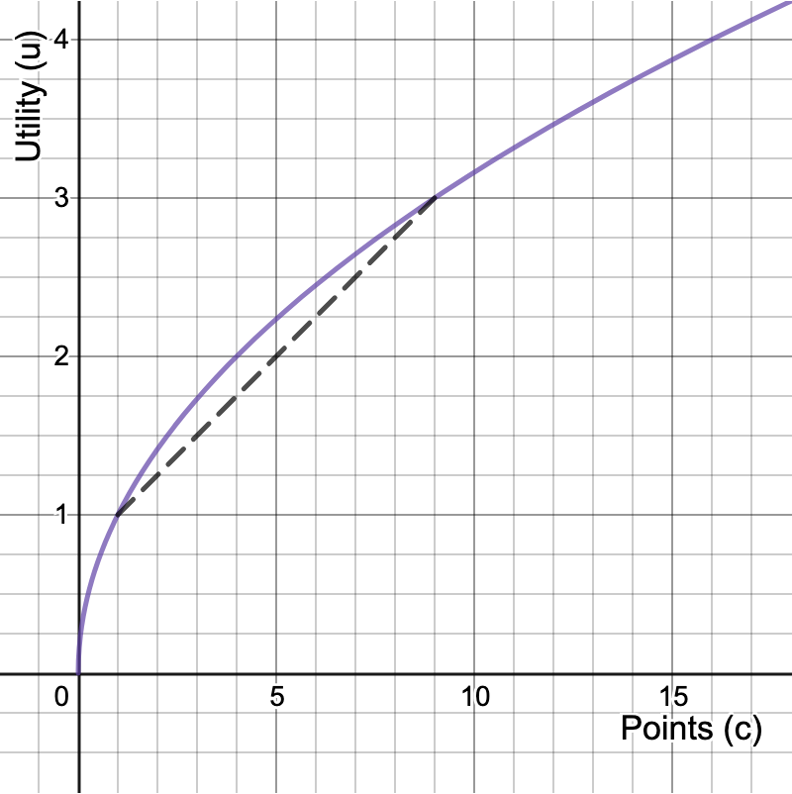

Certainty Equivalent

Suppose your utility from points is given by

Expected value of your utility (u) is:

What amount \(CE\), if you had it for sure, would give you the same utility?

Indifference curve for 2 utils

Certainty Equivalent

Certainty Equivalent = 4

Expected Points = 5

Risk Premium = 1

Risk Premium

How much would you be willing to pay to avoid risk?

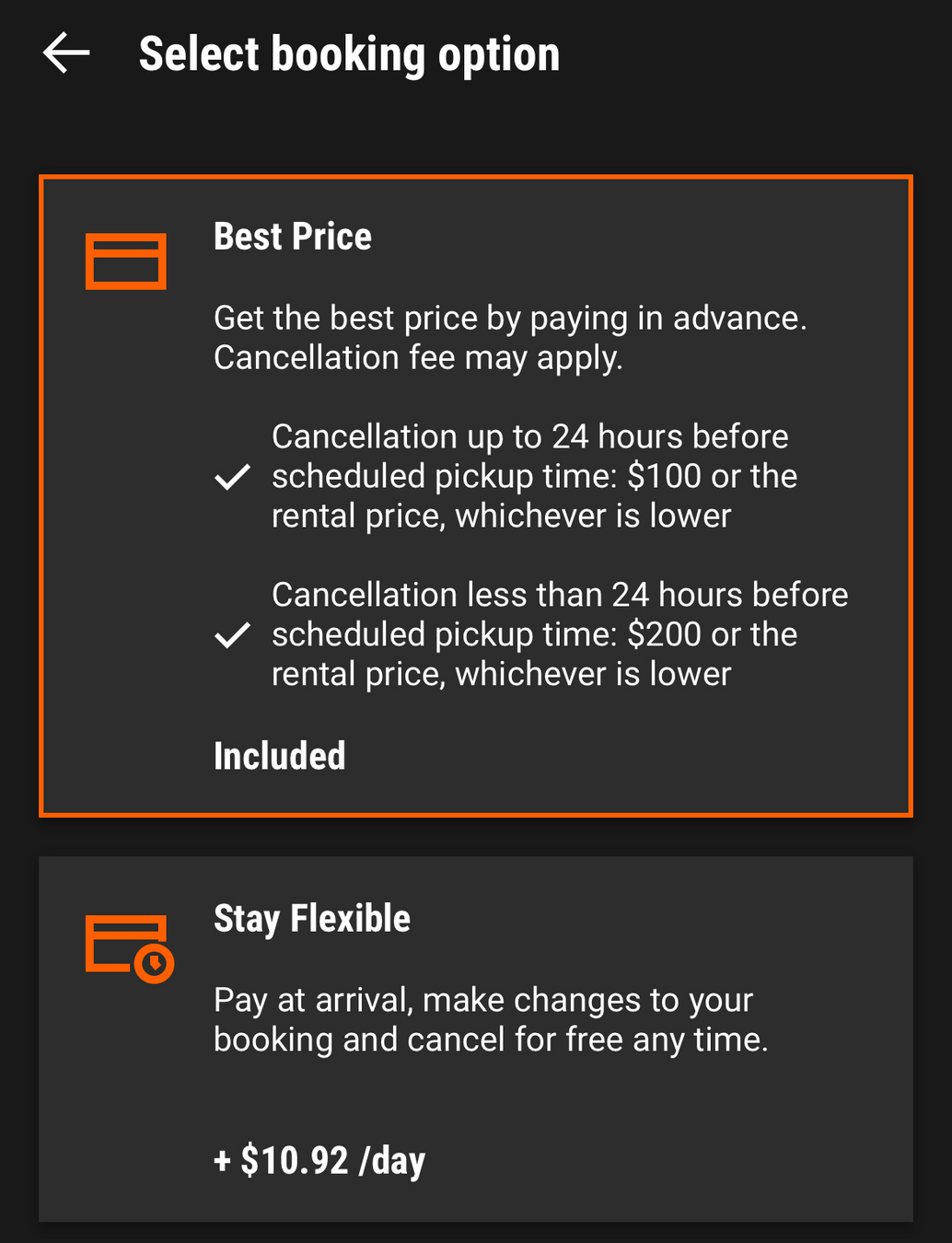

What is Sixt offering me here?

Example 1: Betting on a Coin Toss

Example 2: Deal or No Deal

Start with $250 for sure

Would you do it?

If you bet $150 on a coin toss,

you would face the lottery:

50% chance of 100, 50% chance of 400

Two briefcases left: $200K and $1 million

Would you accept that offer? What's the highest offer you would accept?

The "banker" offers you $561,000 to walk away; or you could pick one of the cases.

A lottery is a set of outcomes,

each of which occurs with a known probability.

Lotteries

Example 1: Betting on a Coin Toss

Start with $250 for sure

If you bet $150 on a coin toss,

you would face the lottery:

50% chance of 100,

50% chance of 400

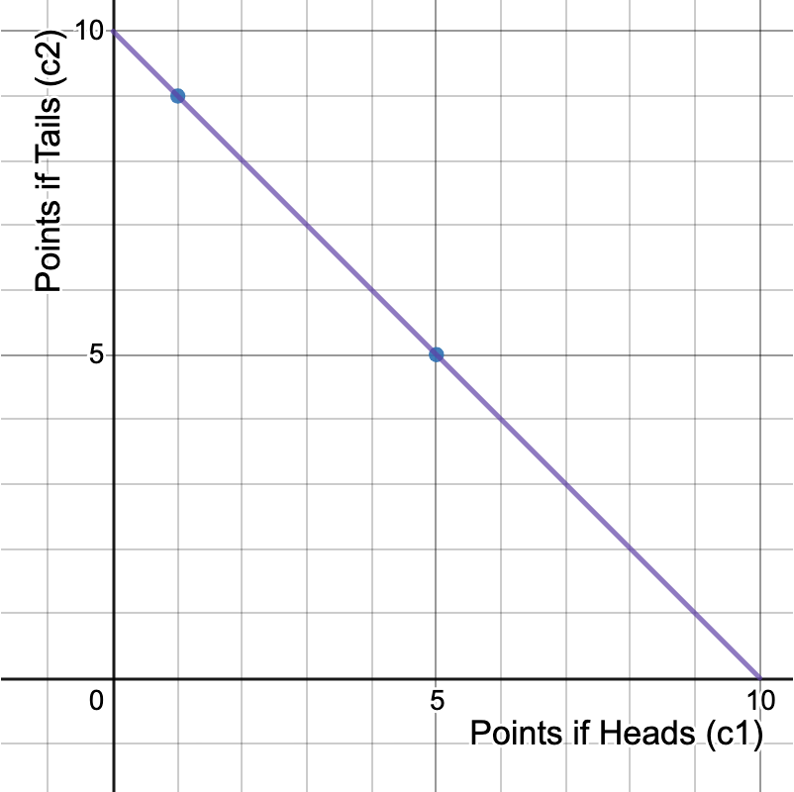

We can represent a lottery as a "bundle" in "state 1 - state 2 space"

Suppose the way you feel about money doesn't depend on the state of the world.

Independence Assumption

Payoff if don't take the bet: \(u(250)\)

Payoff if win the bet: \(u(400)\)

Payoff if lose the bet: \(u(100)\)

Expected Utility

"Von Neumann-Morgenstern Utility Function"

Probability-weighted average of a consistent within-state utility function \(u(c_s)\)

Last time: \(c_1\), \(c_2\) represented

consumption in different time periods.

This time: \(c_1\), \(c_2\) represent

consumption in different states of the world.

Comparison to intertemporal consumption

Marginal Rate of Substitution

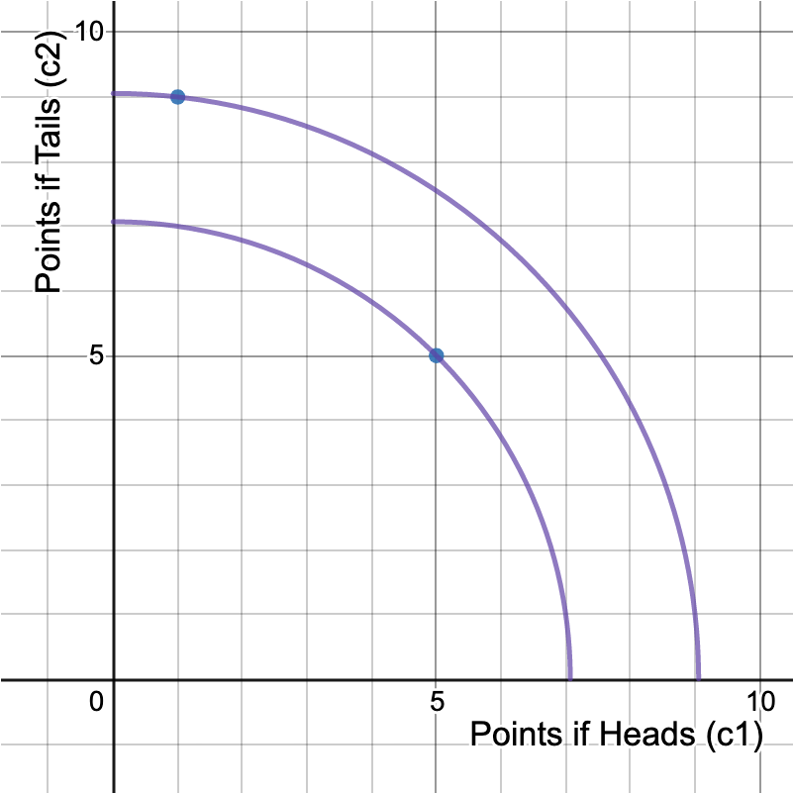

You prefer having E[c] for sure to taking the gamble

You're indifferent between the two

You prefer taking the gamble to having E[c] for sure

Risk Aversion

You prefer having E[c] for sure to taking the gamble

You're indifferent between the two

You prefer taking the gamble to having E[c] for sure

Certainty Equivalence

"How much money would you need to have for sure

to be just as well off as you are with your current gamble?"

Risk Premium

"How much would you be willing to pay to avoid a fair bet?"

Market Implications

How do markets allow us to shift our consumption across states of the world?

Case 1: Insurance

Case 2: Risky Assets

Money in good state

Money in bad state

35,000

25,000

Suppose you have $35,000. Life's good.

If you get into a car accident, you'd lose $10,000, leaving you with $25,000.

You might want to insure against this loss by buying a contingent contract that pays you $K in the case of a car accident.

Money in good state

Money in bad state

35,000

25,000

You want to insure against this loss by buying a contingent contract that pays you $K in the case of a car accident. Suppose this costs $P.

Now in the good state, you have $35,000 - P.

In the bad state, you have $25,000 - P + K.

35,000 - P

25,000 + K - P

Budget line