Price Discrimination

and a review of the past 20 weeks

Christopher Makler

Stanford University Department of Economics

Econ 51: Lecture 19

Both of these are models of asymmetric information: an uninformed party is trying to extract behavior or information from an informed party.

Last time:

The Principal-Agent Model

Today:

Price Discrimination

- Buyers differ as to their valuation of quality: some value it a lot, others not so much

- A seller cannot observe how much the buyer values quality

- Offers a menu of options: a "budget" product at a low price point, and a "premium" product at a higher price point

- Goal: have buyers sort themselves

- A "principal" wants an "agent" to do something for them

- The principal cannot observe how much effort the agent puts forward, but can observe if the agent is successful

- Offers a wage contract with two values: one if the agent fails, the other if they succeed

- Goal: encourage effort

Price Discrimination

- Neoclassical model: perfect competition, single price, price-taking

- Real world: firms with market power engage in lots of interesting kinds of pricing strategies

- Transportation: single tickets vs. monthly passes

- Cell phone plans: pre-paid vs. unlimited

- Airline tickets

- College tuition

- Asymmetric information problem: the firm doesn't know how much its customers value its product. How can it design different options that encourage customers to self-select based on their preferences?

Different Options for Different Customers

- The firm is going to have different "offerings" aimed at different customers.

- One possibility: bundles of quantities

- Another possibilities: quality choice

Quantity Options

Charge and pay as you go

$1 per point

Rides are 5-8 points each

$109.95 + tax

Unlimited rides through 2023

No blackout dates

Quality Options

Quality Options

Only too often does the sight of third-class passengers travelling in open or poorly sprung carriages,

and always badly seated, raise an outcry against the barbarity of the railway companies.

It wouldn't cost much, people say, to put down a few yards of leather and a few pounds of horsehair, and it is worse than avarice not to do so...

It is not because of the few thousand francs which would have to be spent to put a roof over the third-class carriages or to upholster the third class seats that some company or other has open carriages with wooden benches; it would be a small sacrifice for popularity.

What the company is trying to do is to prevent the passengers who can pay the second-class fare from traveling third class; it hits the poor, not because it wants to hurt them, but to frighten the rich.

- Emile Dupuit, 19th century French railroad engineer

Model Setup

Firm chooses to produce goods with quality \(q\)

Type 1 (low value)

There are two types of consumers, who value quality differently.

Type 2 (high value)

Assume (for now) equal numbers in each group

Assume the firm has no costs; they are just trying to maximize their revenue.

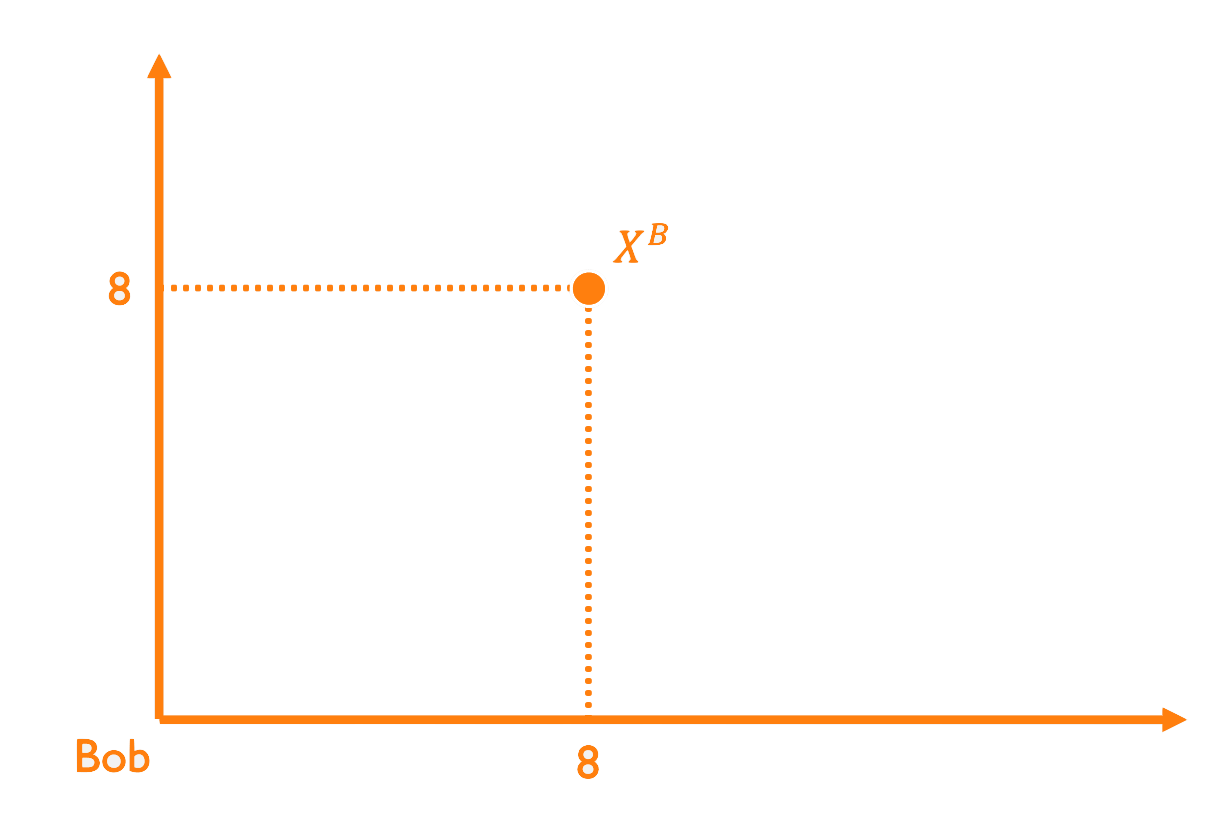

First-Degree Price Discrimination

Type 1 (low value)

Type 2 (high value)

Suppose the firm can observe the type of each customer, and offer them a quality just suited to them — and charge them their total willingness to pay.

What qualities will it produce?

What will it charge?

"Budget offering"

"Premium offering"

What would happen if the consumer's type was unobservable to the seller?

Second-Degree Price Discrimination

Type 1 (low value)

Type 2 (high value)

Now suppose the firm cannot observe the type of the consumer.

Each consumer will buy the good which gives them the most surplus (benefit minus cost)

We don't have to worry about the Type-1 consumers buying the premium product

Might the Type-2 consumers want to buy the budget product, though...?

Second-Degree Price Discrimination

Type 1 (low value)

Type 2 (high value)

Charge low-value types their maximum willingness to pay:

Constraint for high-value types: prefer to buy \(q_2\) at price \(p_2\) than \(q_1\) at price \(p_1\):

Notice: the price you can charge for the premium product depends on how nice the budget product is. The crappier the budget version, the more you can charge for premium...

Second-Degree Price Discrimination

Type 1 (low value)

Type 2 (high value)

Notice: the price you can charge for the premium product depends on how nice the budget product is. The crappier the budget version, the more you can charge for premium...

Second-Degree Price Discrimination

Type 1 (low value)

Type 2 (high value)

Expected revenue if equal numbers of each type:

Take the derivative and set equal to zero:

Mechanisms: A Review

- In each of the models we saw this week, one of the players designs a choice for the other player

- Principal-agent: incentivize the other player to behave in a certain way, even though behavior can't be monitored

- Price discrimination: incentivize the other player to reveal their preferences by giving them a menu of options

- How many games in the real world are designed...and by whom...and for what (profit-making) purpose...?

What have we learned in our 20 weeks together?

At the core of everything is the concept of choice.

Two Kinds of Optimization

Tradeoffs between two goods

Optimal quantity of one good

🍎

(not feasible)

(feasible)

🍌

Optimal choice

🙂

😀

😁

😢

🙁

🍎

benefit and cost per unit

Marginal Cost

Marginal Benefit

Optimal choice

Individual agents make choices.

Systems result in outcomes as a result of the collective choices being made within them.

Consumers

Firms

Governments

Markets

Games

Mechanisms

Checkpoint 1: October 13

Model 1: Trading

Model 3: Strategic Interactions

with Incomplete Information

Checkpoint 2: November 3

WEEK 1

WEEK 2

WEEK 3

Preferences

Exchange Economies

Production Economies

WEEK 4

WEEK 5

Analyzing a Game from a Player's POV

Static Games of Complete Information

Checkpoint 3: November 17

Final Exam: December 11 (cumulative)

WEEK 6

WEEK 7

WEEK 8

Dynamic Games of Complete Information

Static Games of Incomplete Information

Dynamic Games of Incomplete Information

WEEK 9

WEEK 10

Getting people to do what you want

Getting people to reveal information

Model 4: Interactions with Asymmetric Information

Different Types of Interactions

Model 2: Strategic Interactions with Complete Information

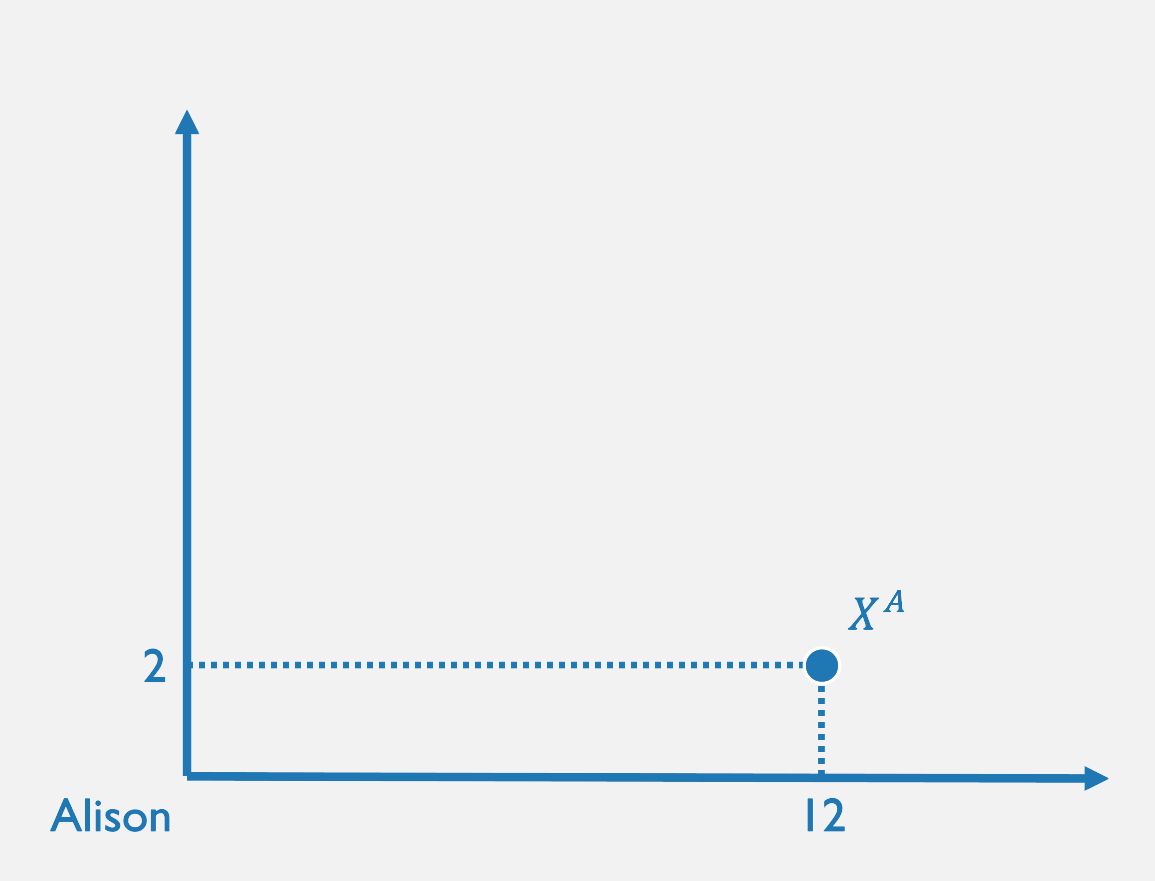

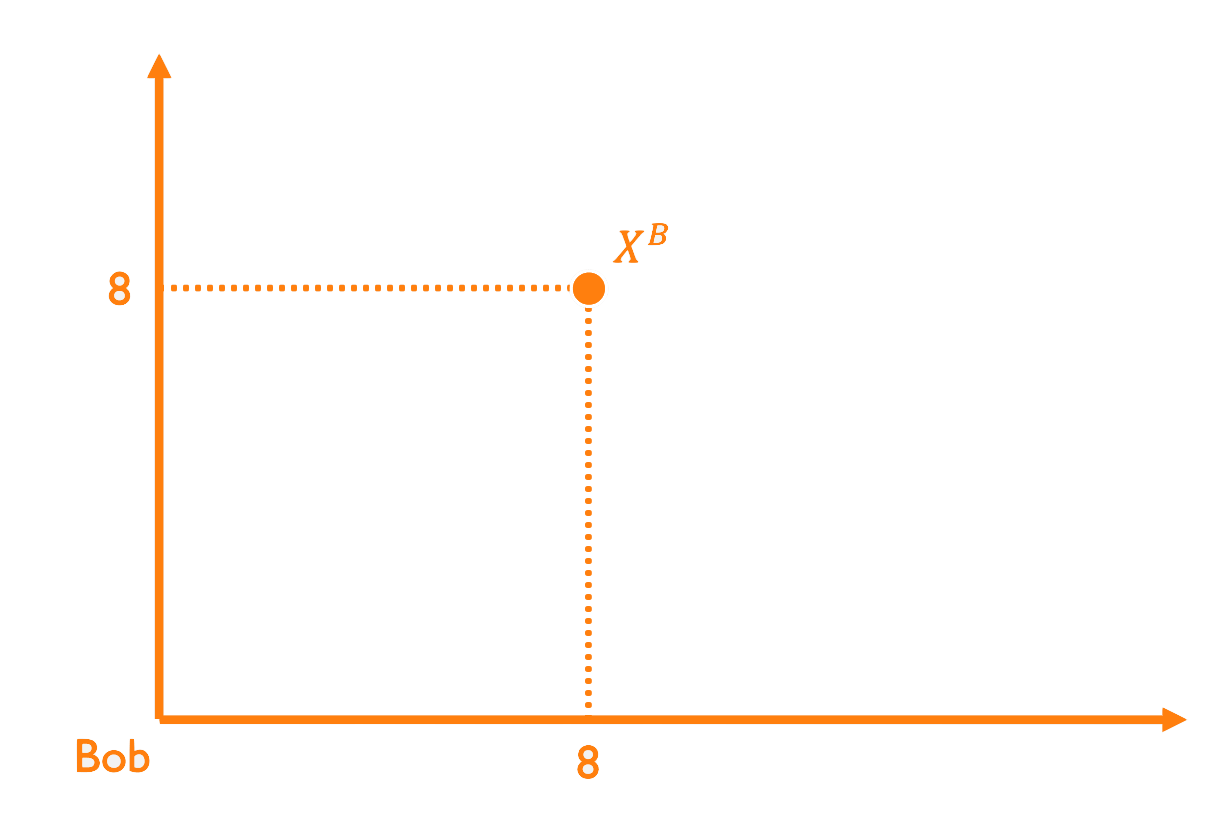

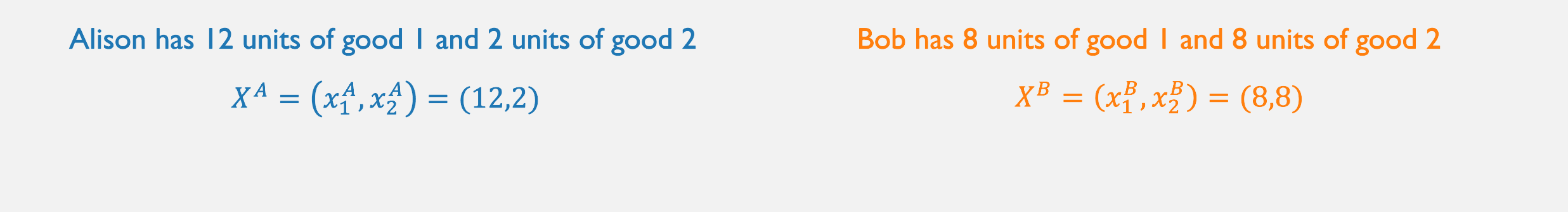

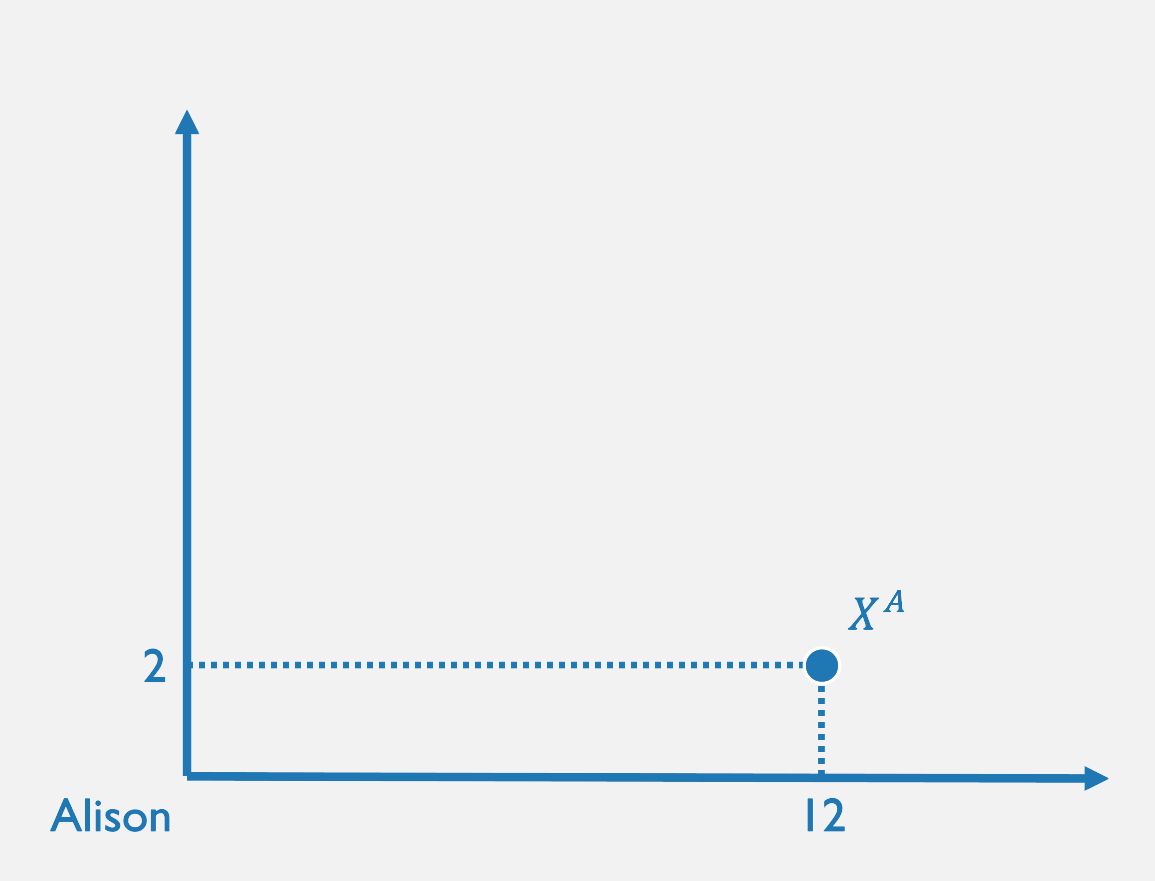

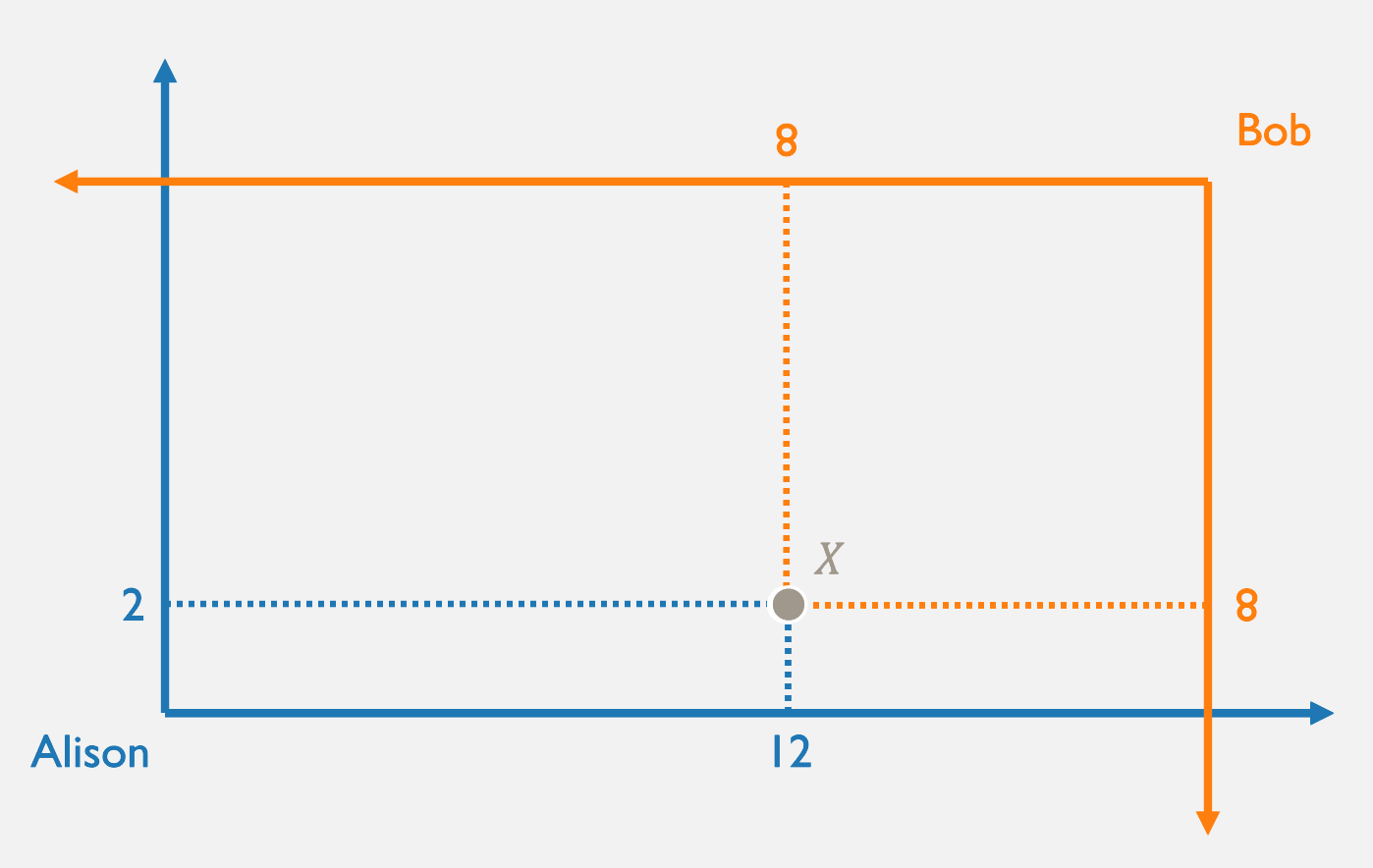

From Bundles to Allocations

From Bundles to Allocations

From Bundles to Allocations

Preferences in the Edgeworth Box

What does the "lens" of overlap represent?

How is the existence of this lens related to

the agents' marginal rate of substitution (MRS) at point \(X\)?

Pareto Improvements and Pareto Efficiency

A reallocation that makes at least one person strictly better off and makes nobody strictly worse off is called a Pareto improvement.

An allocation from which

there is a possible Pareto improvement is called a

Pareto inefficient allocation.

An allocation from which

there is no possible Pareto improvement is called a

Pareto efficient allocation.

Pareto Efficiency and the Contract Curve

The parameters \(a\) and \(b\) represent how much A and B like good 1, respectively:

Game Theory

- Players: who is playing the game?

- Actions: what can the players do at different points in the game?

- Information: what do the players know when they act?

- Outcomes: what happens, as a function of all players' choices?

- Payoffs: what are players' preferences over outcomes?

Components of a Game

Strategies and Strategy Spaces

A strategy is a complete, contingent plan of action for a player in a game.

This means that every player

must specify what action to take

at every decision node in the game tree!

A strategy space is the set of all strategies available to a player.

Time

Information

Static

(Simultaneous)

Dynamic

(Sequential)

Complete

Incomplete

WEEK 5

WEEK 6

LAST TIME

TODAY

Prisoners' Dilemma

Cournot

Entry Deterrence

Stackelberg

Auctions

Job Market Signaling

Collusion

Cournot with Private Information

Poker

Time

Information

Static

(Simultaneous)

Dynamic

(Sequential)

Complete

Incomplete

Strategy: an action

Equilbirium: Nash Equilibrium

Strategy: a mapping from the history of the game onto an action.

Equilibrium: Subgame Perfect NE

Strategy: a plan of action that

specifies what to do after every possible history of the game, based on one's own private information and (updating) beliefs about other players' private information.

Equilibrium: Perfect Bayesian Equilibrium

Strategy: a mapping from one's private information onto an action.

Equilibrium: Bayesian NE

WEEK 5

WEEK 6

LAST TIME

TODAY

Prisoners' Dilemma

Cournot

Entry Deterrence

Stackelberg

Auctions

Job Market Signaling

Collusion

Cournot with Private Information

Poker

Definition: Best Response (Nash) Equilibrium

In plain English: in a Nash Equilibrium, every player is playing a best response to the strategies played by the other players.

In other words: there is no profitable unilateral deviation

given the other players' equilibrium strategies.

1

2

1

2

,

4

3

,

1

4

,

1

1

,

T

M

L

C

B

R

3

0

,

2

1

,

3

2

,

8

0

,

8

0

,

Nash equilibrium occurs when every player is choosing strategy which is a

best response to the strategies chosen by the other player(s)

Definition: Subgame Perfect Nash Equilibrium

In an extensive-form game of complete and perfect information,

a subgame in consists of a decision node and all subsequent nodes.

A Nash equilibrium is subgame perfect if the players' strategies

constitute a Nash equilibrium in every subgame.

(We call such an equilibrium a Subgame Perfect Nash Equilibrium, or SPNE.)

Informally: a SPNE doesn't involve any non-credible threats or promises.

1

2

X

Y

X

Y

A

B

3

2

1

0

2

0

1

3

C

D

1

2

2

AC

AD

BC

BD

3

2

1

0

2

0

1

3

3

2

1

3

2

1

0

0

What are the Nash equilibria of this normal-form game?

1

2

X

Y

X

Y

A

B

3

2

1

0

2

0

1

3

C

D

1

2

2

AC

AD

BC

BD

3

2

1

0

2

0

1

3

3

2

1

3

2

1

0

0

Think about this: after player 1 makes her move, we are in one of two subgames.

What should player 2 do in each subgame?

1

2

X

Y

X

Y

A

B

3

2

1

0

2

0

1

3

C

D

1

2

2

AC

AD

BC

BD

Think about this: after player 1 makes her move, we are in one of two subgames.

3

2

1

0

2

0

1

3

3

2

1

3

2

1

0

0

What should player 2 do in each subgame?

Anticipating how player 2 will react, therefore, what will player 1 choose?

Definition: Bayes Nash Equilibrium

A strategy in a simultaneous game of incomplete information is a mapping from each agent's private information onto their actions.

A Bayes Nash Equilibrium is the Nash equilibrium of the game with such strategies.

Games of

Incomplete Information

A

B

X

Y

1

2

2

0

2

0

0

4

0

4

A

B

X

Y

1

2

0

4

2

0

2

0

0

4

Suppose one of these

two games is being played.

Both players know there is an equal probability of each game.

Only player 1 knows which game is being played right now.

What is player 1's strategy space?

Player 2's?

Nature

Heads

(1/2)

Tails

(1/2)

Both players know there is an equal probability of each game.

Only player 1 knows which game is being played right now.

We can model this "as if" there is a nonstrategic player called Nature who moves first,

2

1

2

1

X

Y

2

0

2

0

0

4

0

4

X

Y

0

4

2

0

2

0

0

4

X

Y

X

Y

\(A^H\)

\(B^H\)

\(A^T\)

\(B^T\)

flips a coin, and picks which game is being played based on the coin flip.

Player 1 observes Nature's move, so they have to choose what to do if Nature flips Heads (\(A^H\) or \(B^H\)) and if Nature flips Tails (\(A^T\) or \(B^T\)).

Player 2 does not, so their information set spans the entire game: they are only choosing X or Y.

Nature

Heads

(1/2)

Tails

(1/2)

2

1

2

1

\(A^H\)

\(B^H\)

X

Y

1

2

2

0

2

0

0

4

0

4

\(A^T\)

\(B^T\)

X

Y

0

4

2

0

2

0

0

4

X

Y

X

Y

The Bayesian Normal Form representation of the game shows the expected payoffs for each of the strategies the players could play:

\(A^HA^T\)

\(A^HB^T\)

\(B^HA^T\)

\(B^HB^T\)

X

Y

1

2

1

0

3

1

0

2

0

1

3

2

2

0

2

4

Bayes Nash Equilibrium is the NE of this game. It maps private information onto (simultaneously taken) actions.

Definition: Perfect Bayesian Equilibrium

Consider a strategy profile for the players, as well as beliefs over the nodes at all information sets.

These are called a perfect Bayesian Equilibrium (PBE) if:

- Each player’s strategy is optimal to them at each infoset, given beliefs at this infoset and opponents’ strategies (“Sequential Rationality”)

- The beliefs are obtained from strategies using Bayes’ Rule wherever possible (i.e. at each infoset that is reached with a positive probability) (“consistency of beliefs”)

Job Market Signaling

Nature determines each worker's type; \({1 \over 3}\) are H, \({2 \over 3}\) are L.

NATURE

Type-H Worker

Type-L Worker

The worker realizes their own type,

and chooses whether to go to college

or stick with a high school degree.

Firms cannot observe the worker's type;

they can only observe whether

they chose High School or College.

The firm has beliefs about the worker's type based on that choice:

Job Market Signaling

NATURE

Type-H Worker

Type-L Worker

Consider a separating equilibrium in which type-H workers choose College, and type-L workers choose High School:

What are the firm's beliefs?

Reason: if all type-H's choose College,

and all type-L's choose High School,

then observing the worker's choice conveys all relevant information to the firm.

Job Market Signaling

NATURE

Type-H Worker

Type-L Worker

Consider a separating equilibrium in which type-H workers choose College, and type-L workers choose High School:

What are the firm's beliefs?

What is the firm's best response to workers' strategies and this set of beliefs?

Job Market Signaling

NATURE

Type-H Worker

Type-L Worker

Candidate separating equilibrium:

Important! A PBE must specify

both strategies and beliefs.

Also...we're not done!!!

We need to check that workers don't want to deviate given the strategies of firms.

Mechanism Design

Game

Players

Strategies

Payoffs

Mechanism

Players with Hidden Information

Actions

Outcomes

Given this game,

what outcome do we predict will happen?

Given a desired outcome,

what game can we design to achieve it?

"Reverse Game Theory"

If people have hidden information,

(e.g. the quality of a used car for sale)

what mechanism can a designer establish

to get them to reveal that information?

If people can take hidden actions,

what mechanism can a designer establish

to get them to choose the action the designer wants them to take?

ADVERSE SELECTION

MORAL HAZARD

Big Ideas

- At the core of every model are people making decisions.

- To "solve" a problem, you have to start by understanding what makes those people tick.

- You then have to analyze the ways in which people are interacting with one another

- Time and information are the key determinants of how people will interact with one another.

- Your boss will never ask you to set up a Lagrangian or solve for the off-the-equilibrium-path beliefs which will sustain a pooling perfect Bayes equilibrium

- But hopefully, these courses will help you make better choices, and give you frameworks for productive interactions in your life and your work.