Dr James Cummings

Can We Make It Easier

To Do the Right Thing?

Infrastructure for digital scholarly editing

James.Cummings@newcastle.ac.uk

@jamescummings

CC+BY (press space to cycle through slides)

Overview

- About the TEI: A quick high-level refresher

- What do people do now: Creating and publishing digital editions

- An example project: William Godwin's Diary

- More about the problem: Infrastructure for digital editions

Thesis: TEI is the right format for scholarly digital editions, but we still lack a de facto solution for collaborative creation, annotation, publication and analysis which understands why editors make particular decisions

About the TEI:

A quick high-level refresher

The TEI (The Text Encoding Initiative) is:

- An international consortium of institutions, projects and individual members

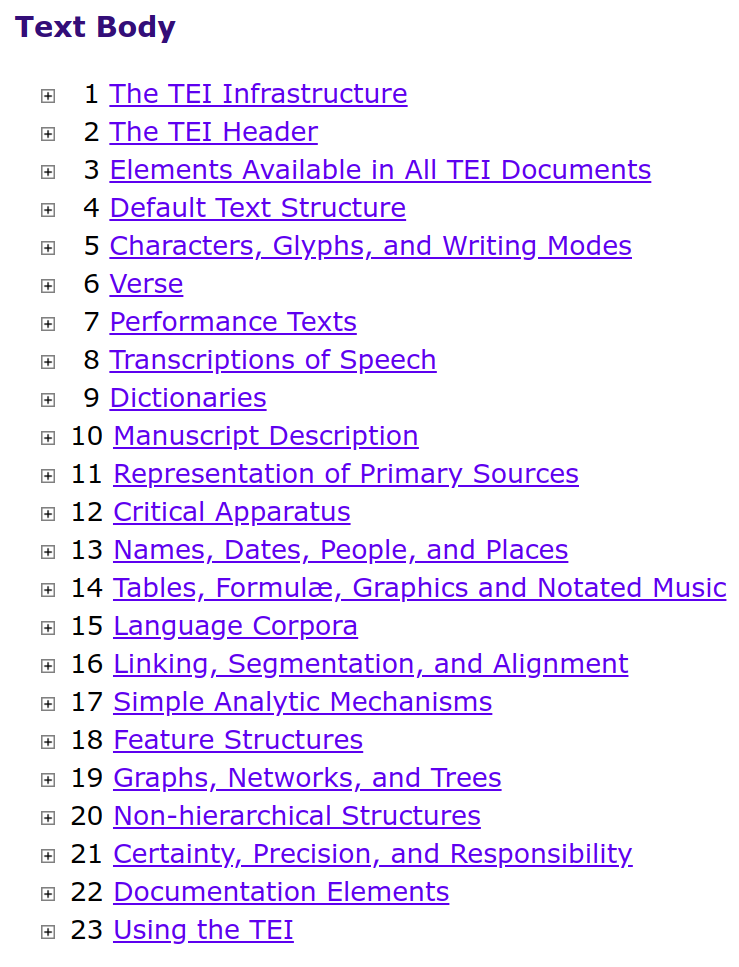

- A freely available manual of set of regularly maintained and updated recommendations: 'The Guidelines' with definitions, examples, and discussion of over 575 markup distinctions

- A mechanism for producing customized schemas for validating your project's digital texts or metadata

- A set of free and openly licensed, customizable tools and stylesheets for transformations to many formats (e.g. HTML, Word, PDF, Databases, RDF/LinkedData, Slides, ePub, etc.)

- A simple consensus-based way of organizing and structuring textual (and other) resources

- An archival, well-understood, format for long-term preservation of digital data and metadata

- Whatever you make it! It is a community of users and volunteers

- The TEI Consortium manages the development of the TEI Guidelines (and associated software)

- It is overseen by an elected Executive Board and its outputs developed by an elected Technical Council

- People don't have to be members to use the standard but this gives them a vote in elections

- The TEI Guidelines are updated about every 6 months

Markup: Why do we use italic fonts?

Think about the uses for an italic font in any form of printed publication. Why might an author/publisher put some text into italics? What are they signalling about that text?

We can usually tell these types of things apart from context. If we want to use these categories, computers need to be told these things are different.

Some common uses include:

- titles

- emphasis

- foreign phrases

- technical terms

- editorial apparatus, captions, cross references

- quotations, speaker labels in drama

- speech and thought ... and many more

About XML

<element> Text </element>

<element attribute="value">

Text or child elements here

</element>

<element attribute="value"/>

"Opening Tag"

"Closing Tag"

"Empty Element"

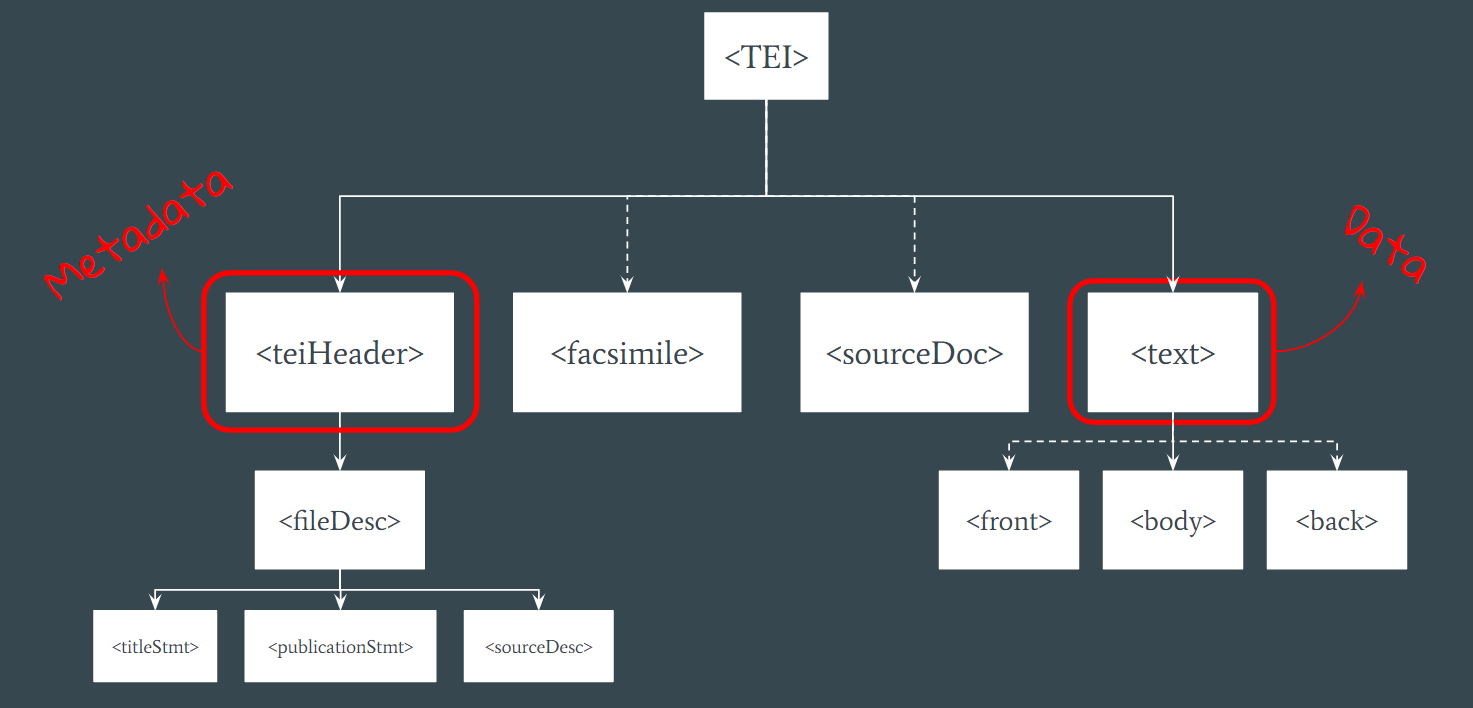

Basic TEI Structure

Usually Encoded as TEI XML

The TEI Guidelines

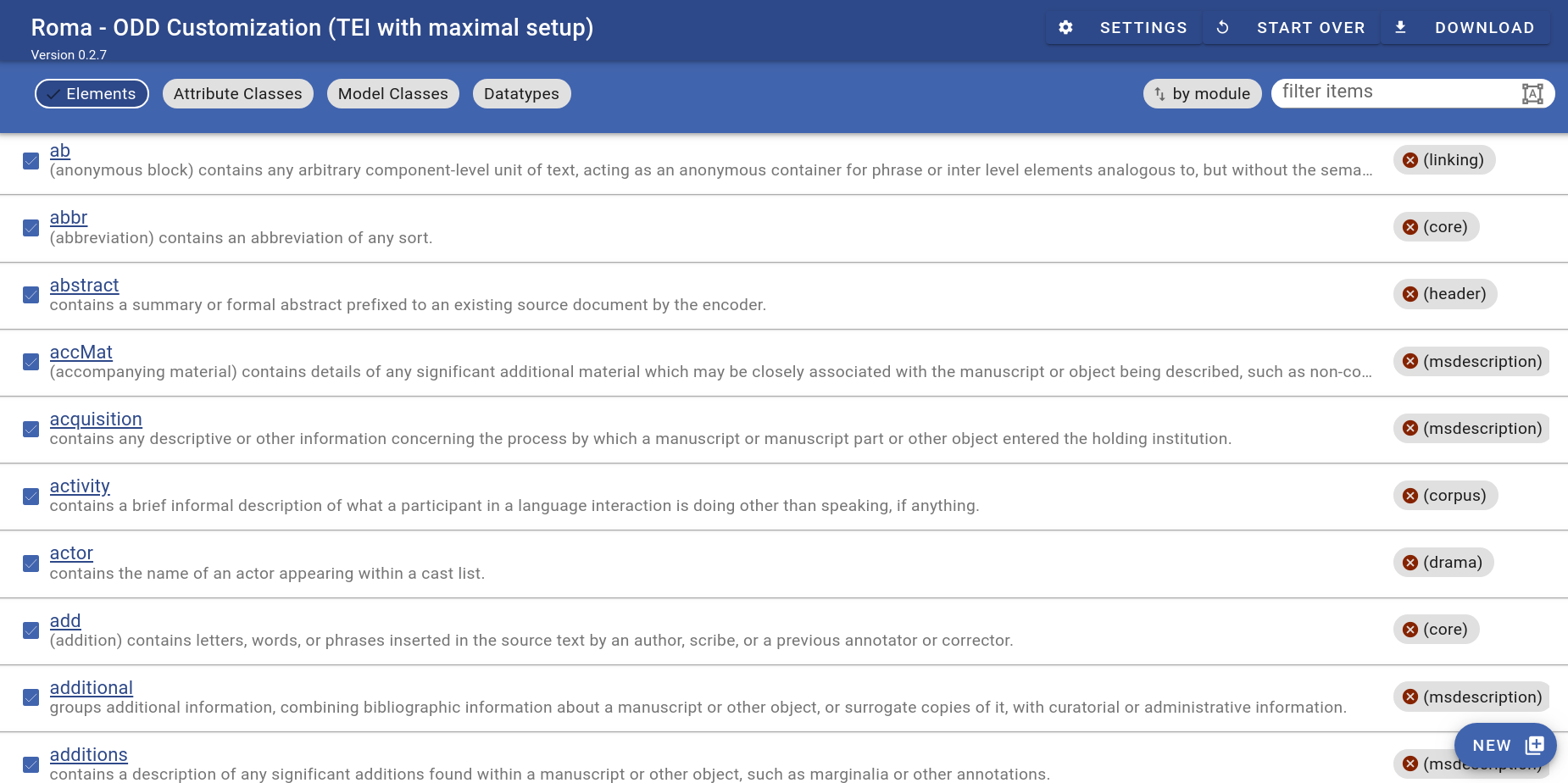

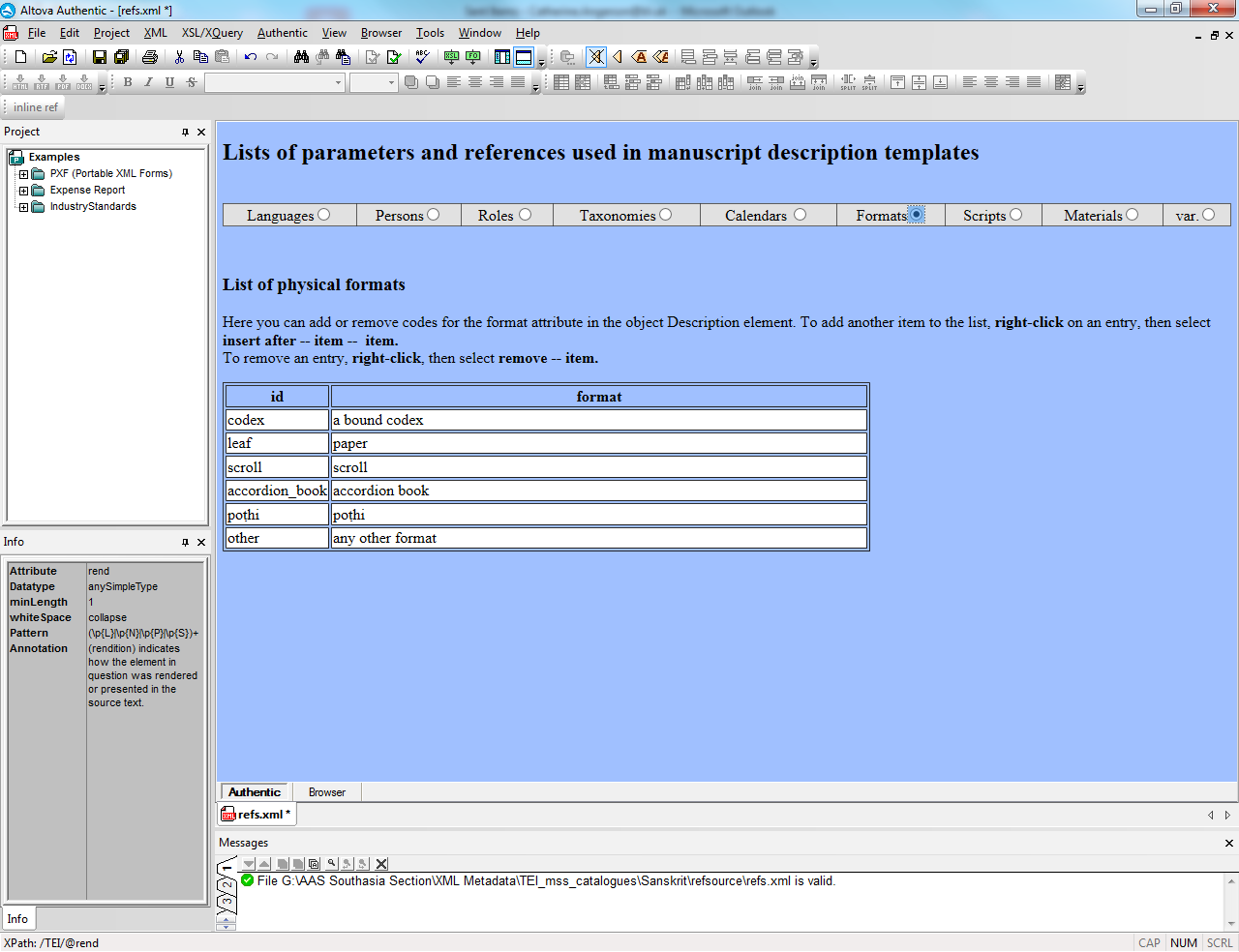

TEI Customisation

(But I don't need everything the TEI provides, or want something it doesn't give me)

Possibilities of the

TEI Framework

Project B

Project A

New Elements

- The ability to interchange many documents improves significantly with a common interchange format

- Customisation can document the differences in a machine processable format so tools can compare different corpora of texts

- @louburnard

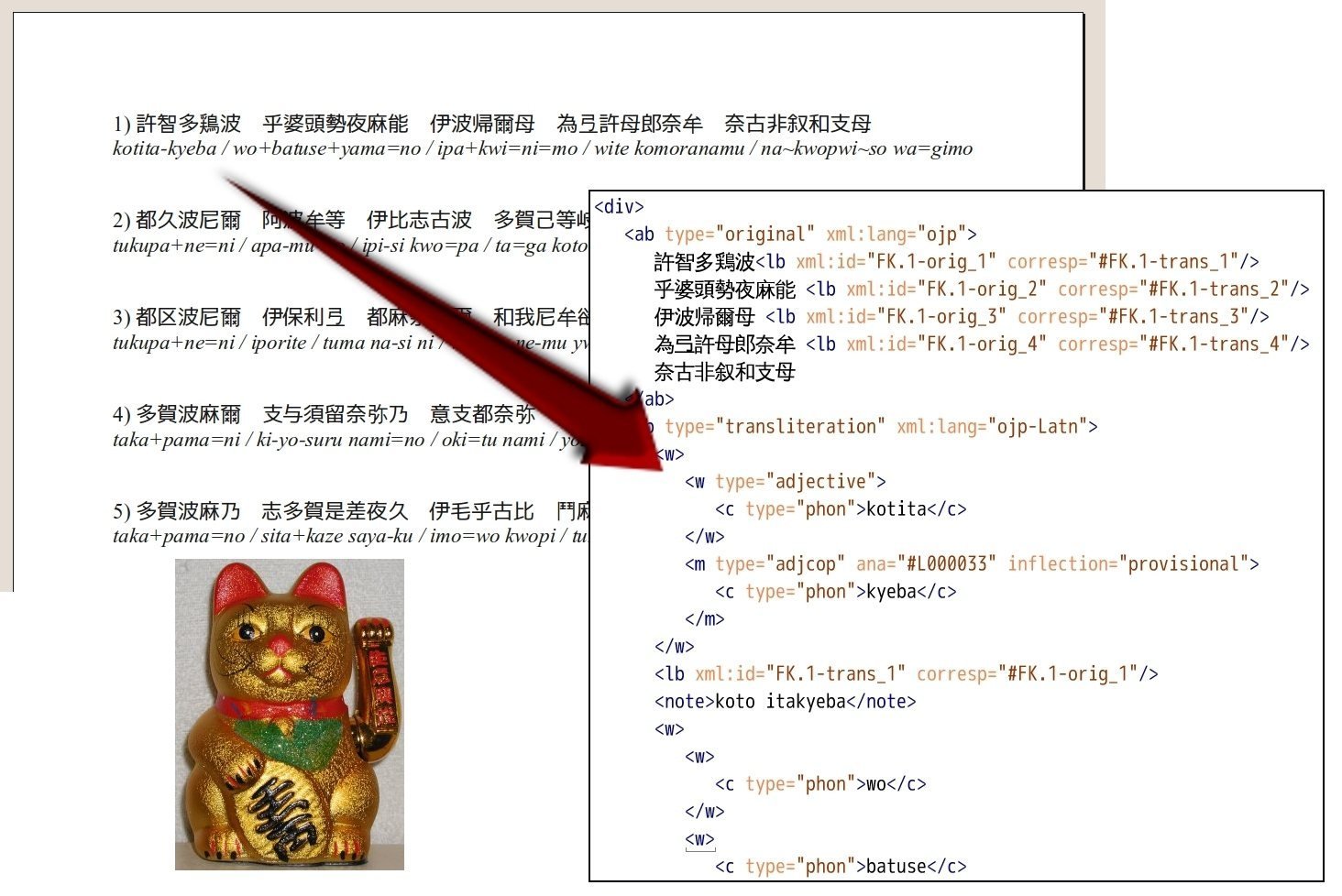

TEI Scope

(What kinds of texts is the TEI good for?)

What Kinds of Documents Can The TEI Cope With?

The TEI takes a generalistic approach to overall text structure and this means it should be able to cope with texts of

any size, any language, any date, any complexity, or any writing system.

This document could be in any form (books, journals, manuscripts, postcards, letters, rolls of papyrus, clay tablets, web pages, gravestones, etc.) and contain any type of text (plays, prose, poems, dictionaries, linguistic corpora, letters, emails, metadata, etc.).

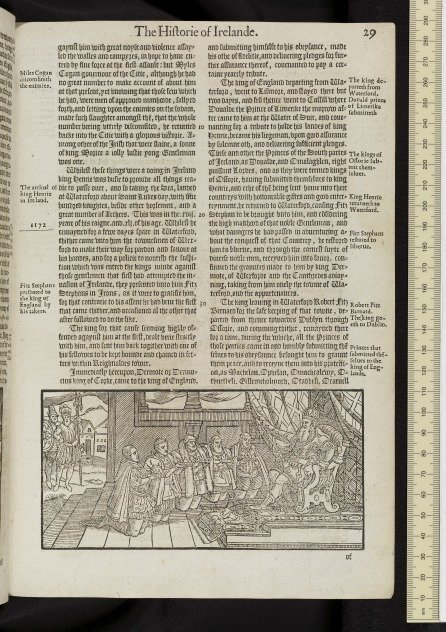

Holinshed's Chronicles: columns, marginal notes, woodcuts

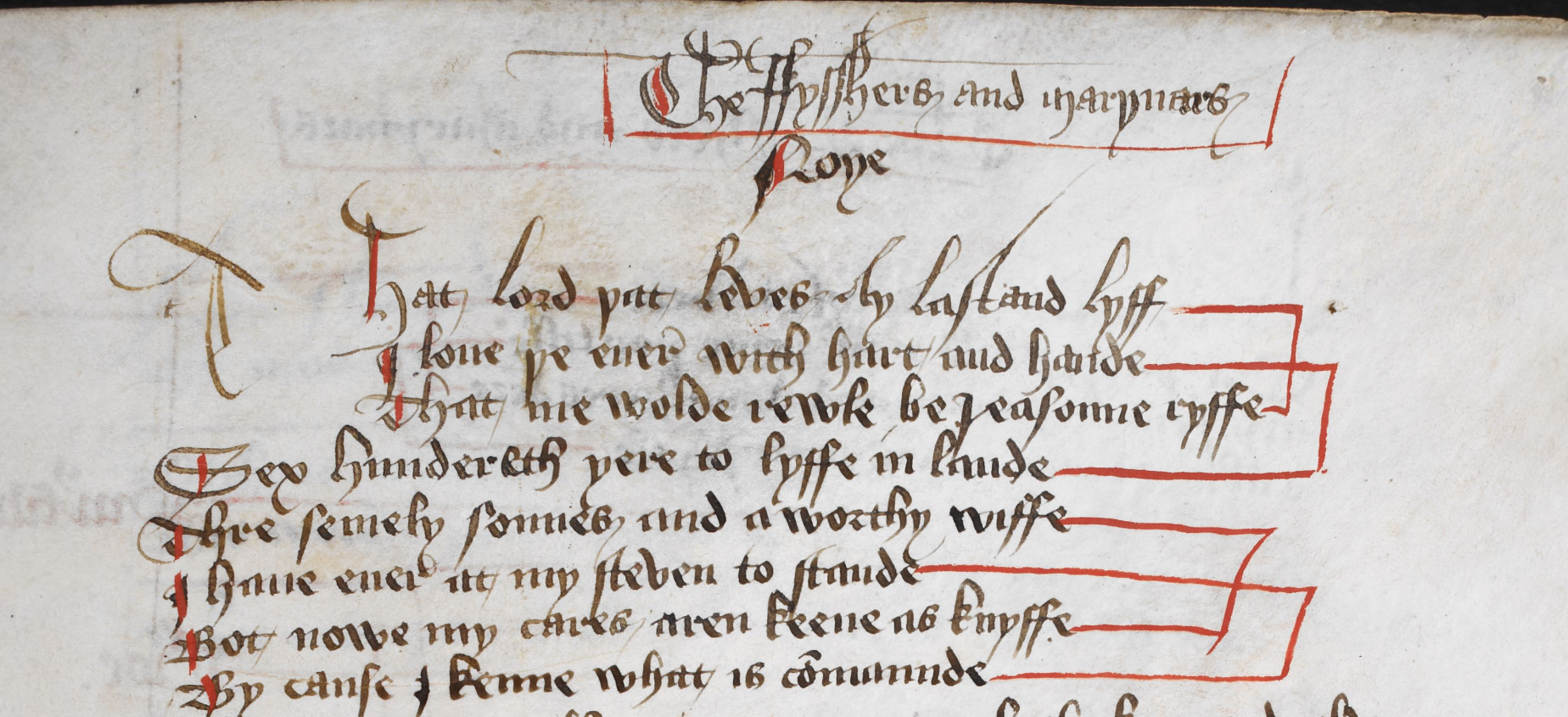

Medieval Drama: (York Cycle, Noah & Flood): Dramatic texts, speeches, rhyme schemes, editorial corrections, etc.

Medieval Manuscripts: full description, translations, stylistic rendering, variants, critical apparatus, editorial commentary, etc.

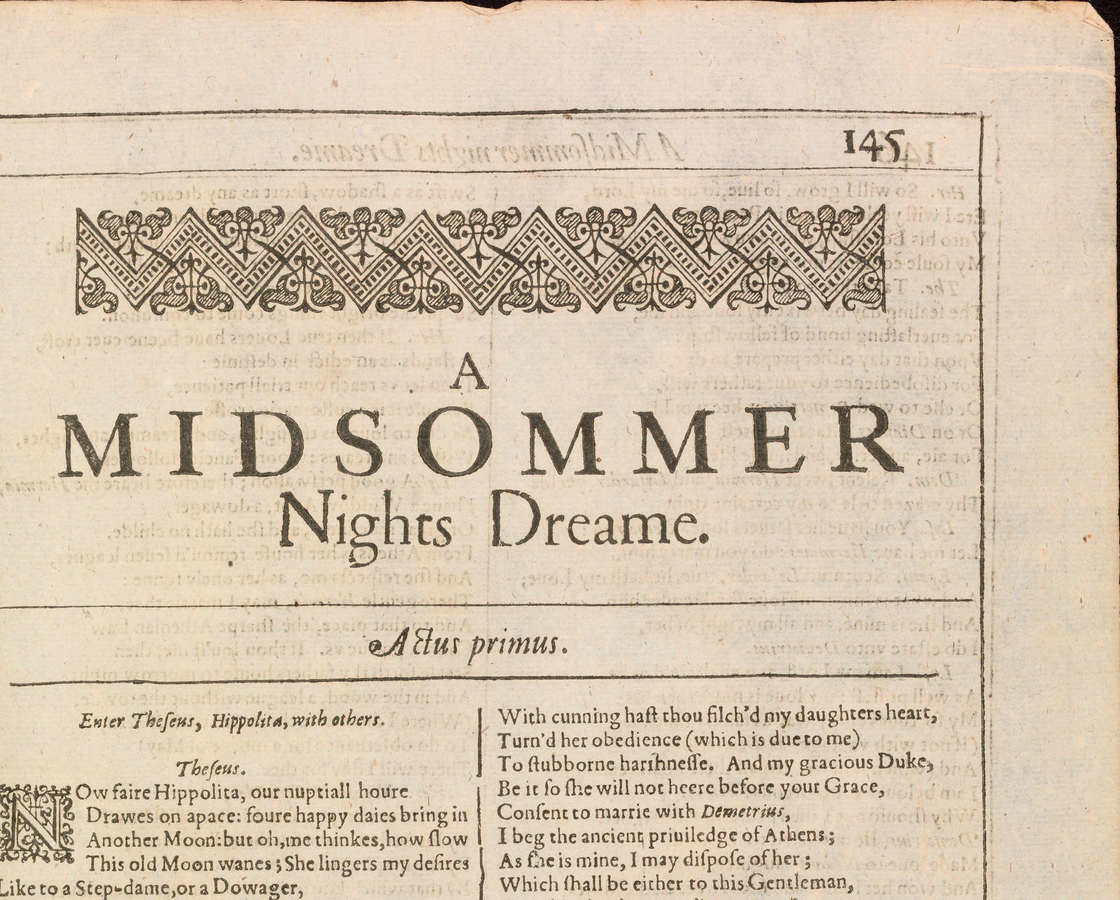

First Folio:

forme-work, catchwords, decorative initials, etc.

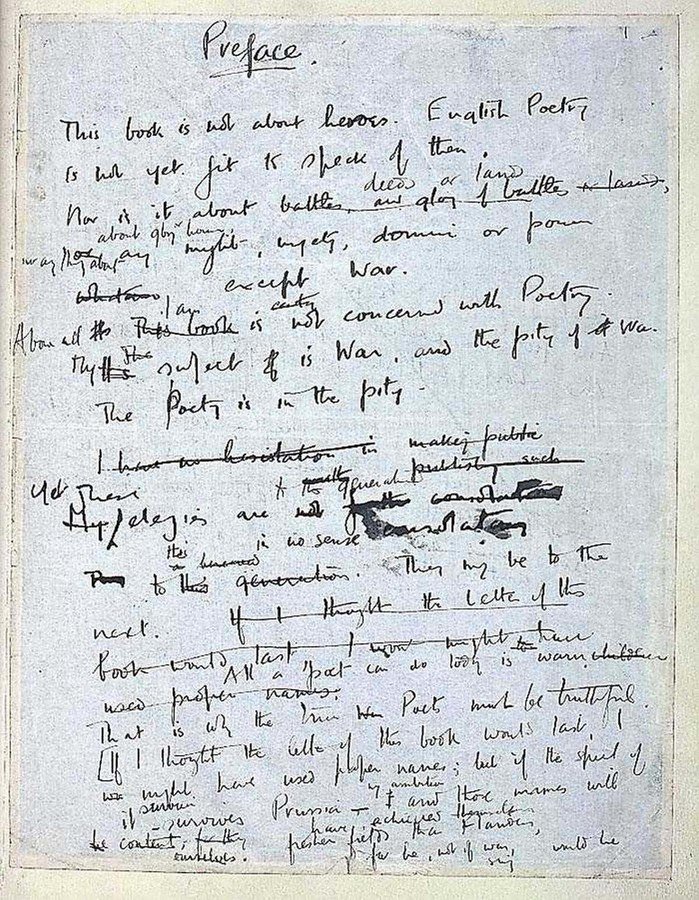

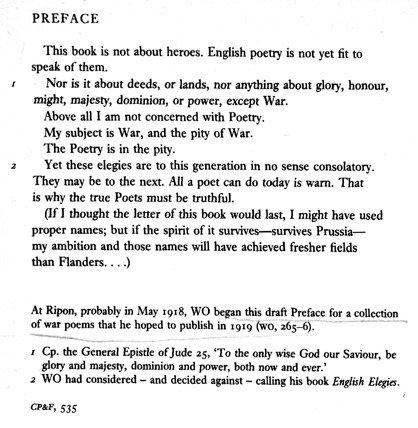

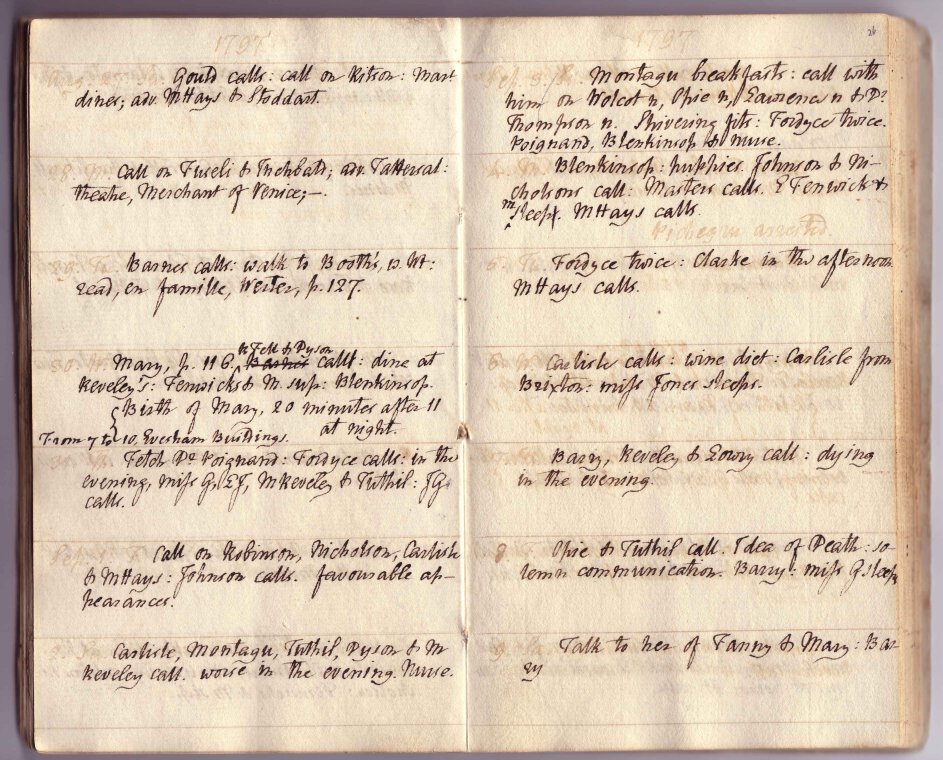

Wilfred Owen: manuscripts, corrections, multiple versions

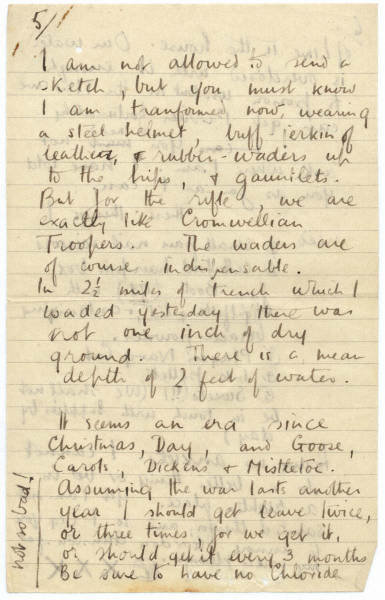

Wilfred Owen: Letters, codewords

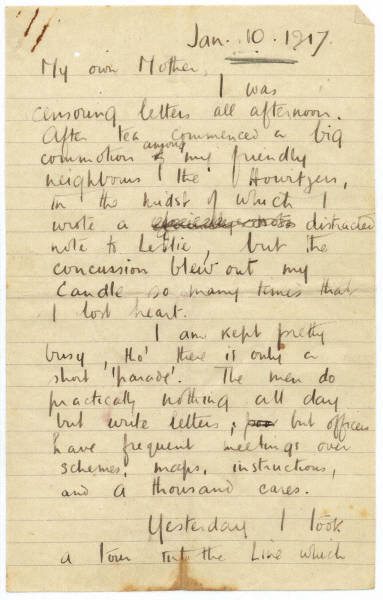

George Herbert: Graphic text layout, poetry

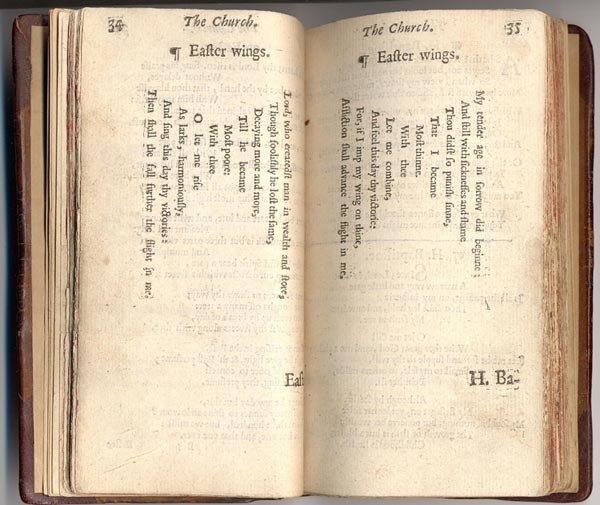

William Godwin's Diary: diary structure, abbreviated texts

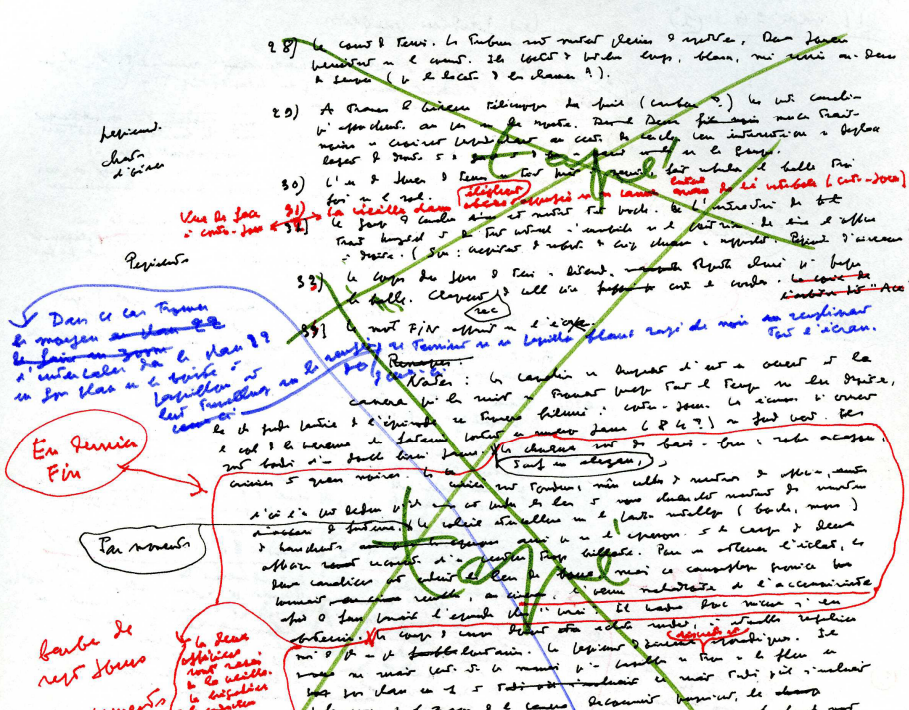

Modern Manuscripts: Genetic editing, many hands, text (re)use, location/orientation on page

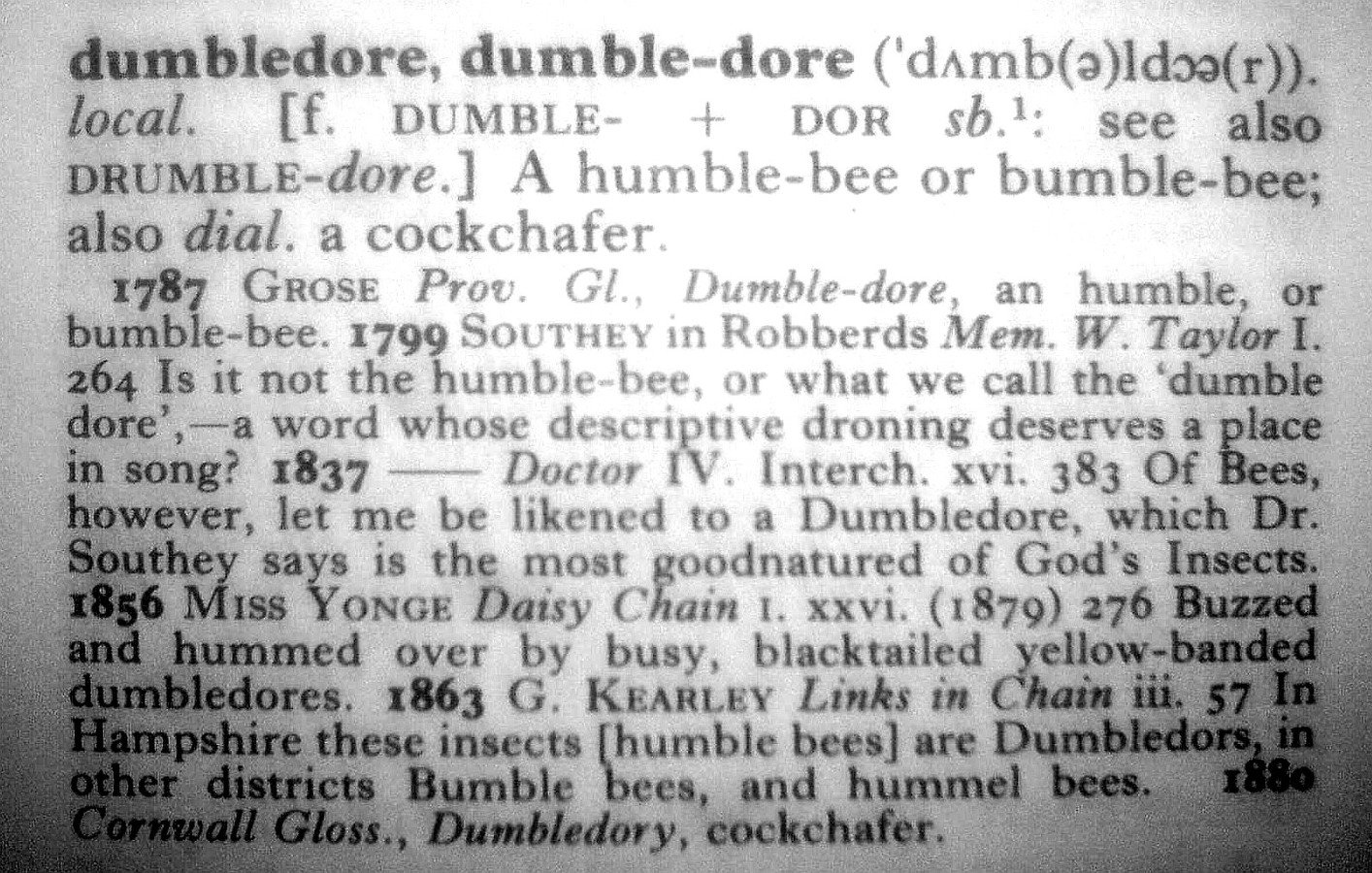

Print and Digital Dictionaries: entries, sense, etymologies, quotations, etc.

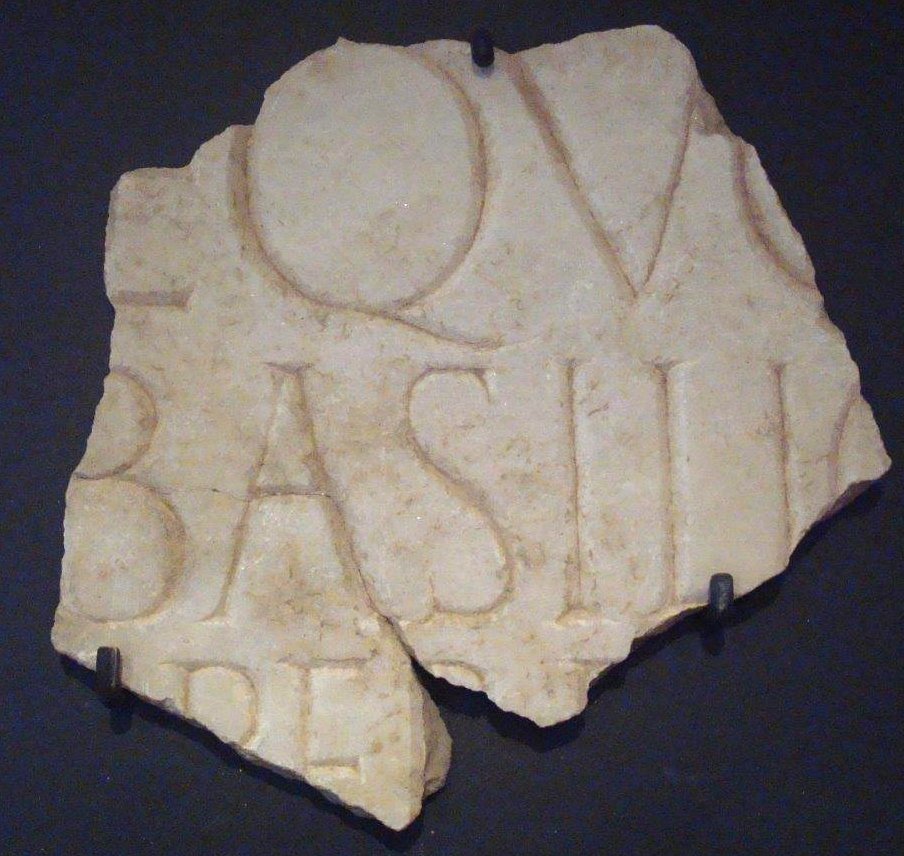

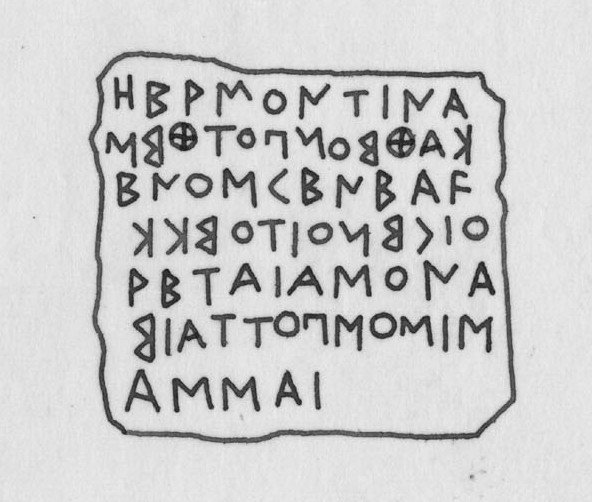

Epigraphical Texts: partial letters, supplied text, physical description

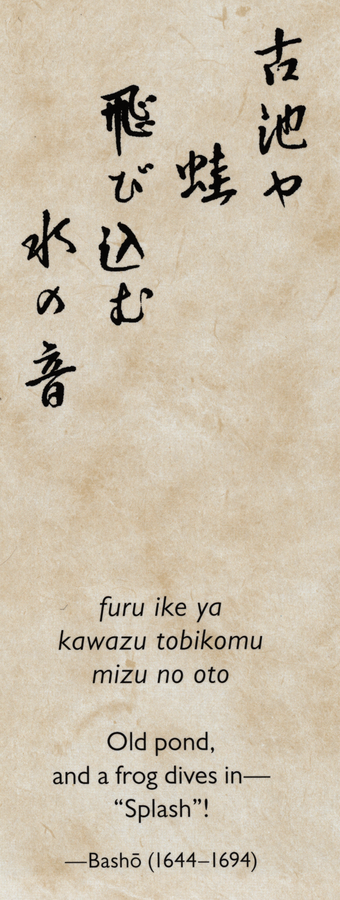

Various writing systems: Unicode/non-Unicode characters, right-to-left, reversing lines, etc.

A Mental Exercise We Often Give Students

Thinking about this material, and indeed your own, what do you think are the things you would like to mark up?

- Make a list of textual phenomena and metadata that are important to capture

- How likely is it that you can mark these up reliably and consistently?

- Could any of these potentially be marked up automatically by a cleverly crafted bit of software you had someone build?

Pretend an authoritarian anti-intellectual government has come to power and, through a series of bad decisions, has to slash your project funding by 50%. What do you do?

- Do you do half the amount of material in the same depth?

- Markup less?

- Invest in more semi-automatic markup?

- Something else?

Repeat the exercise.

Interested In Learning More About The TEI?

SAVE THE DATE:

- Monday 30 March - Friday 3 April 2020

- Second annual "Textual Editing in the Digital Age" Workshop at Newcastle University

- Registration to open in February

- Very low registration charge to cover travel of visiting speakers

- Collaboration between IES and ATNU

What do people do now?

Creating and publishing scholarly digital editions

Creating Scholarly Editions

(Do I have to see the XML markup?)

Creating TEI

- How do people create TEI Files?

- hand encoding

- as individuals, through a variety of editors

- through an interface

- whether various forms, tags-off views in editors, or bespoke content management systems

- up-conversion

- of materials created in other formats, such as docx, xlsx, etc., by a programmer

- hand encoding

Up-conversion

- Often people will create editions through other forms such as MS Word (docx)

- Using the docxtotei conversion that TEI-C freely provides this can be transformed to TEI

- Limited to presentational markup (based on Word formatting styles)

- If you use special word phase-level styles in the form of tei_elementName it tries to convert these to that element (e.g. tei_name to <name>)

- Second phase of conversion work can often provide more detailed markup depending on how granular the original format preserves distinctions

In the end the best method to use is that which enables you actually to create your rich digital texts

Publishing Editions

(How can I publish these TEI files?)

Publishing TEI

- There are many tools available these are only some of the examples of different types of tools. Sadly, often projects create their own bespoke tools.

- Edition Visualization Technology

- TEI Critical Edition Toolbox

- TEI-C Stylesheets

- OxGarage

- CETEIcean

- eXist-db / TEI Publisher

- TAPAS project

- The tools you use may affect the features you can display to those reading your research and you may have more or less ability to customise

Edition Visualization Technology

- Easy publication for multi-witness critical editions

- Critical Edition support: rich and expandable critical apparatus, variant heat map, witnesses collation and variant filtering

- Bookmark: direct reference to the current view of the web application, page and edition level, collated witnesses and selected apparatus entry

- High level of customization: the editor can customize both the user interface layout and the appearance of the graphical components

- https://visualizationtechnology.wordpress.com/

TEI Critical Apparatus Toolbox

- Based on TEI Boilerplate (a simple TEI publishing system)

- The toolbox lets you:

- Check your encoding: offers facilities to display your edition while it is still in the making, and check the consistency of your encoding

- Display parallel versions: choose the sigla of the witnesses, and the different versions of the text, following each chosen witness, will be displayed in parallel columns.

- http://teicat.huma-num.fr/

TEI-C Stylesheets

- Freely available, generalised XSLT stylesheets

- Transformations to and/or from around 40 formats such as:

- BibTeX, COCOA, CSV, DocBook, DocX (MS Word), DTD, EPub, XSL-FO, HTML, JSON, LaTeX, Markdown, NLM, ODT, PDF, RDF, RelaxNG, RNC, Schematron, Slides, TEI Lite, TEI ODD, TEI P4, TEI simplePrint, TCP, Text, Wordpress, XLSX (MS Excel), XSD

- Customisable through importing and overwriting templates; Stylesheets repository allows for local 'profiles'

- TEI-C offers services such as OxGarage which enable pipelined conversion to/from many more formats

- https://github.com/TEIC/Stylesheets

CETEIcean

- CETEIcean is a Javascript (ES6) library that enables TEI P5 XML to be displayed in a web browser without transforming them to HTML

- Instead it registers them with the browser as Custom Elements

- Because the elements are treated as HTML, the HTML it produces is valid, and there are not element name collisions (like HTML <p> vs. TEI <p>)

- http://github.com/TEIC/CETEIcean

Your Edition or Web Page Template

Embedded divisions of custom HTML elements

CETEIcean

JavaScript

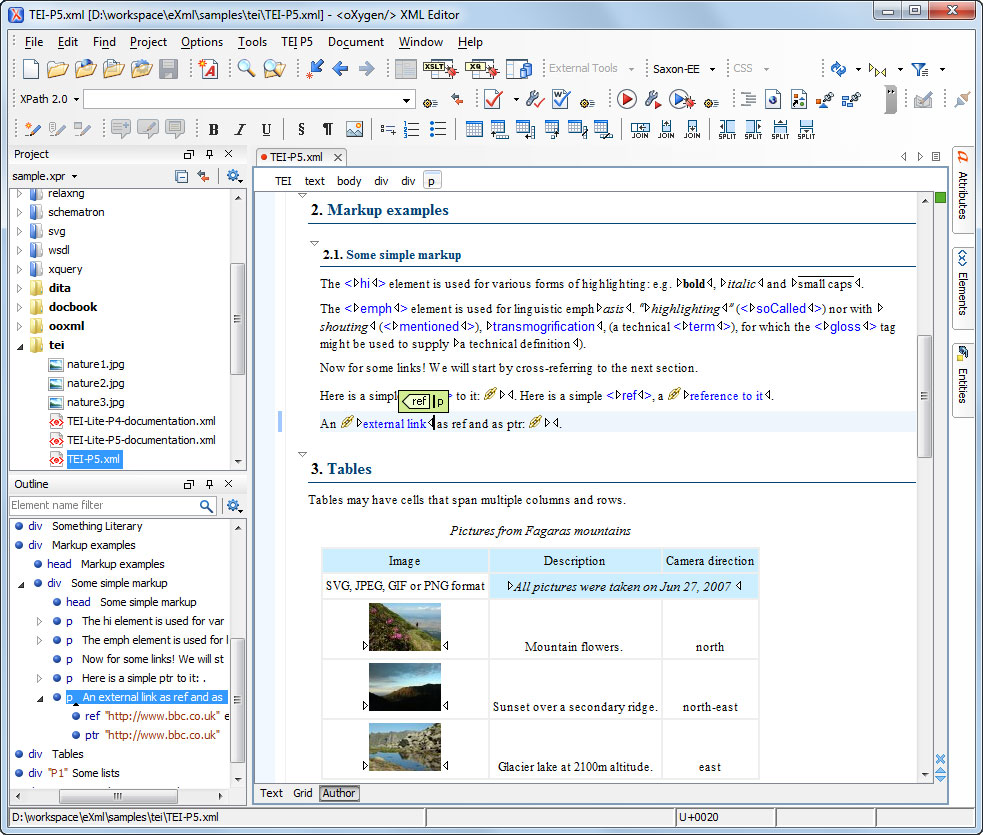

eXist-db TEI Publisher

- The "instant publishing toolbox" based on eXist-db XML database

- Provides easy browsing and search of TEI XML documents initially built for TEI simplePrint

- Default display is clean and sophisticated page-by-page display

- Control of element display is by editing the processing model documentation embedded in the TEI ODD (the TEI customisation format)

- http://www.teipublisher.com/

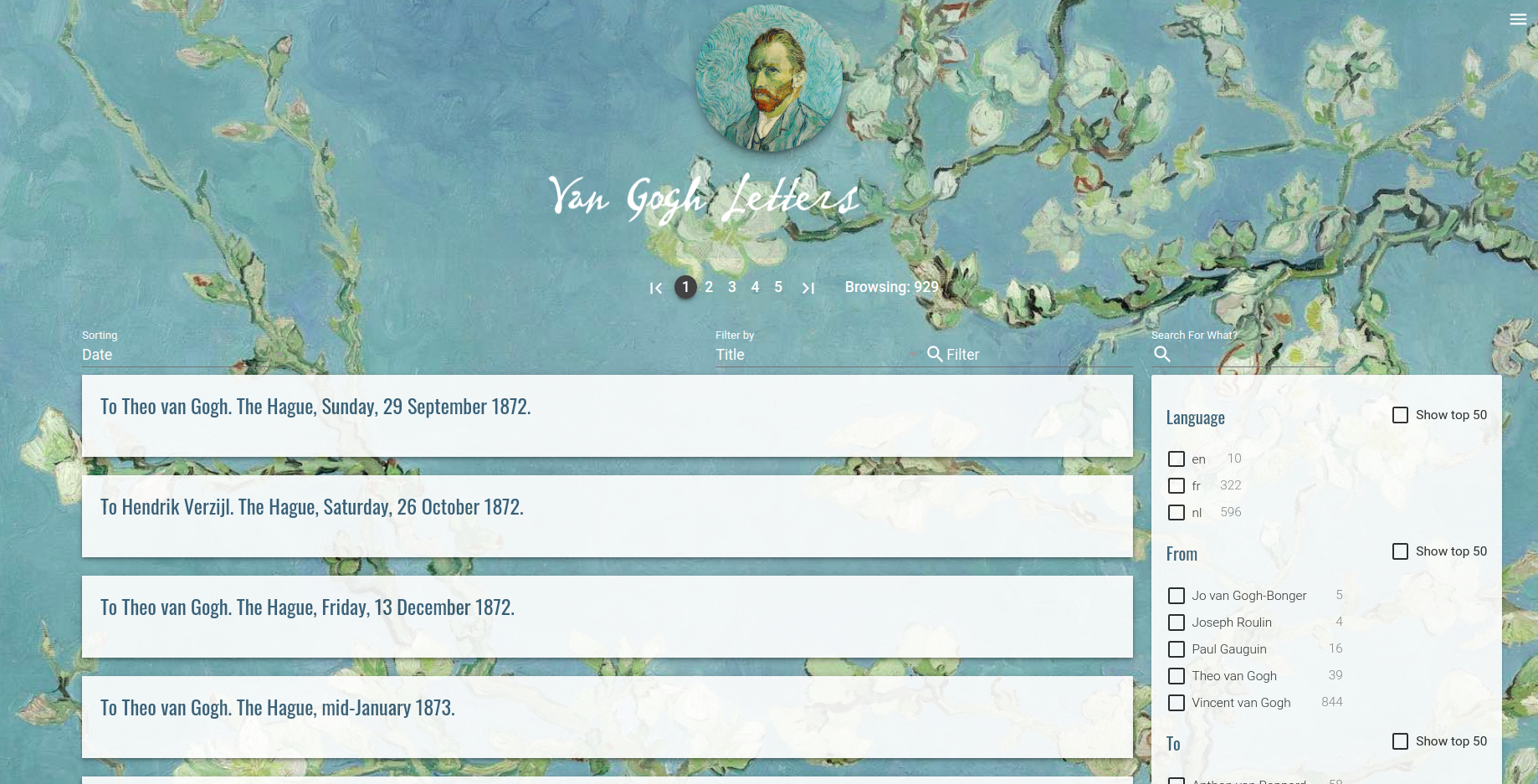

TAPAS Project

- The TAPAS project: TEI Archiving, Publishing, and Access Service hosted by Northeastern University Library's Digital Scholarship Group

- A free account can contribute to projects and collections in TAPAS to archive, publish, discover or share their TEI files

- Built in very basic XSLT transformations

- TEI Members (or paid TAPAS membership) can create collections and projects

- 1GB of XML file storage for TEI files, TEI ODD Customisations

- http://tapasproject.org/

What's wrong with those?

- Nothing.

- But there is no mass adoption of a single solution

- Changing any of those systems involves significant learning curves or expense

- None of it is joined up:

- You use one system to manually create XML

- Another to publish it

- Yet another to analyse it

- If we are to build a new system, it would make sense to base it on one of these -- TEI Publisher being my favourite but even this has its downsides.

Standoff Markup and Editions

- Standoff markup refers to markup or annotation for a text kept separately from the markup (in the same file or in another file

- This gets around any worries of potential overlap of XML structures since as many hierarchies as desired can be encoded simultaneously

- Modern digital editions are often exploiting this, for example having a base text where each word is (automatically) marked up, and other structures like people's names, sentence boundaries, or critical edition apparatus are stored separately and point in to the range of words they concern.

- Almost no generalised editing or publication software understands this approach out of the box.

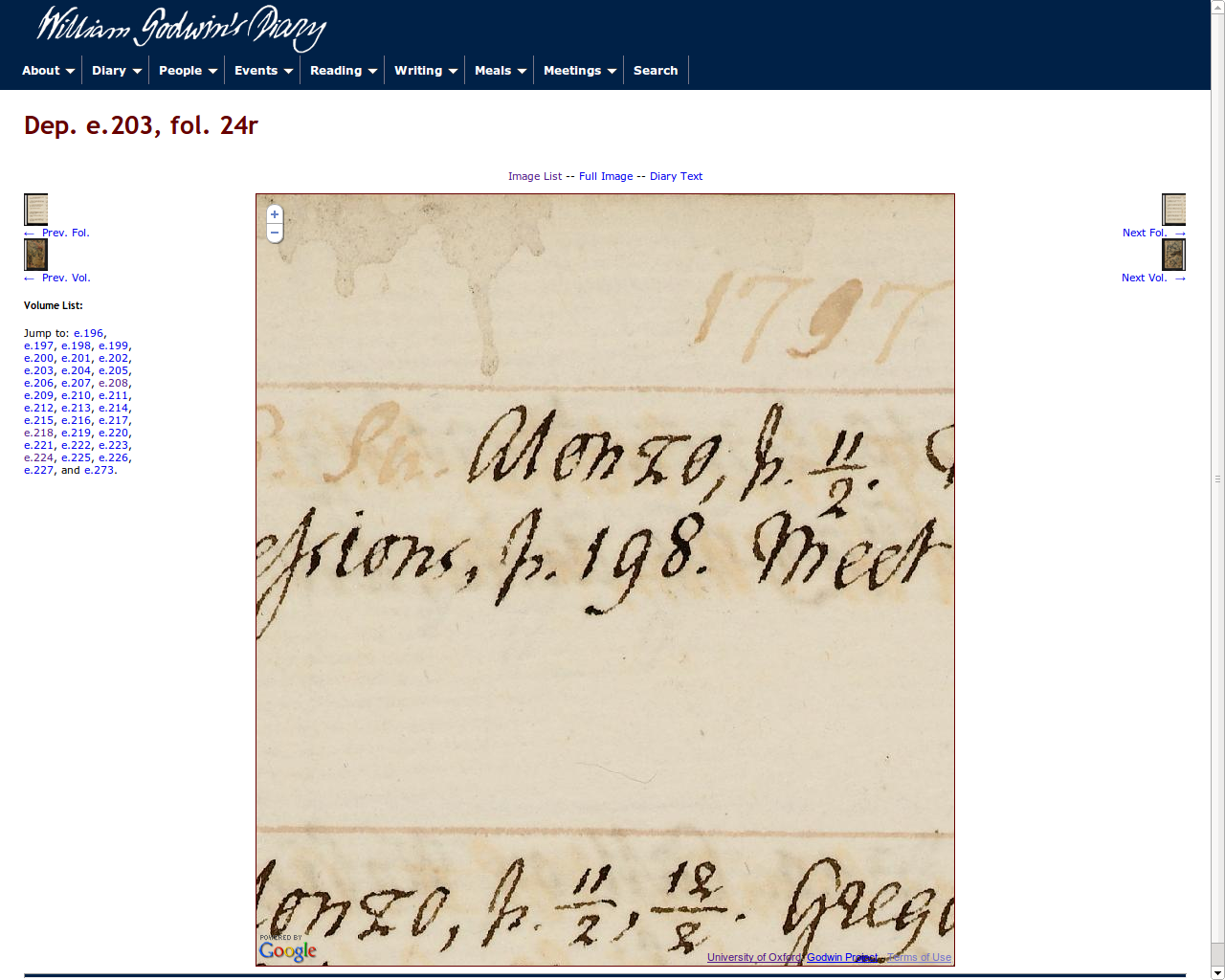

An example project

Case Study:

William Godwin's Diary

About the Godwin's Diary Project

- Godwin was a political philosopher and writer, Mary Wollstonecraft’s husband and Mary Shelley’s father

- University of Oxford project (2007-2010) to create digital edition of William Godwin’s Diary with funding for project from Leverhulme Trust

- Diaries purchased with Abinger Collection based on National Heritage Memorial Fund and donations

- 48 years of diaries in 32 octavo notebooks, written in highly abbreviated daily entries

- People’s names often given as initials

- little detail of substance of meetings

- networks of relationships with people, and aggregate lists of information able to extracted from richly encoded TEI

How did the project get done?

- I trained PI, RA, and 2 PhD students in TEI in 1.5 days

- But had customised the TEI to be about 15 custom elements total

- These were automatically converted back to 'pure' TEI for display and dissemination

- Bespoke website built on top of early version of

eXist-DB (a native XML Database) - Encoders worked in phases adding structural markup, then meetings, then names, etc.

- Each phase they started with a year they had not seen before, proofreading each others work

- As technical consultant I was on hand to answer all and any technical problems

So it worked for that project?

- Yes but:

- it only worked because I so drastically limited their exposure to the richness of TEI,

- and was able to hold their hands through technical issues. This is not a luxury all research projects get.

- Also, its markup being different from other TEI projects in Oxford means no one there now knows much about the data (the PI has also left)

- Its code being bespoke and just for that project means that no one there knows how the publication system works

- It being over 10 years old means it doesn't leverage more recent initiatives like IIIF for image display

- It is definitely an 'at-risk' site which is low on the list of priorities for the Bodleian

More about the problem:

Infrastructure for

Digital Textual Editing

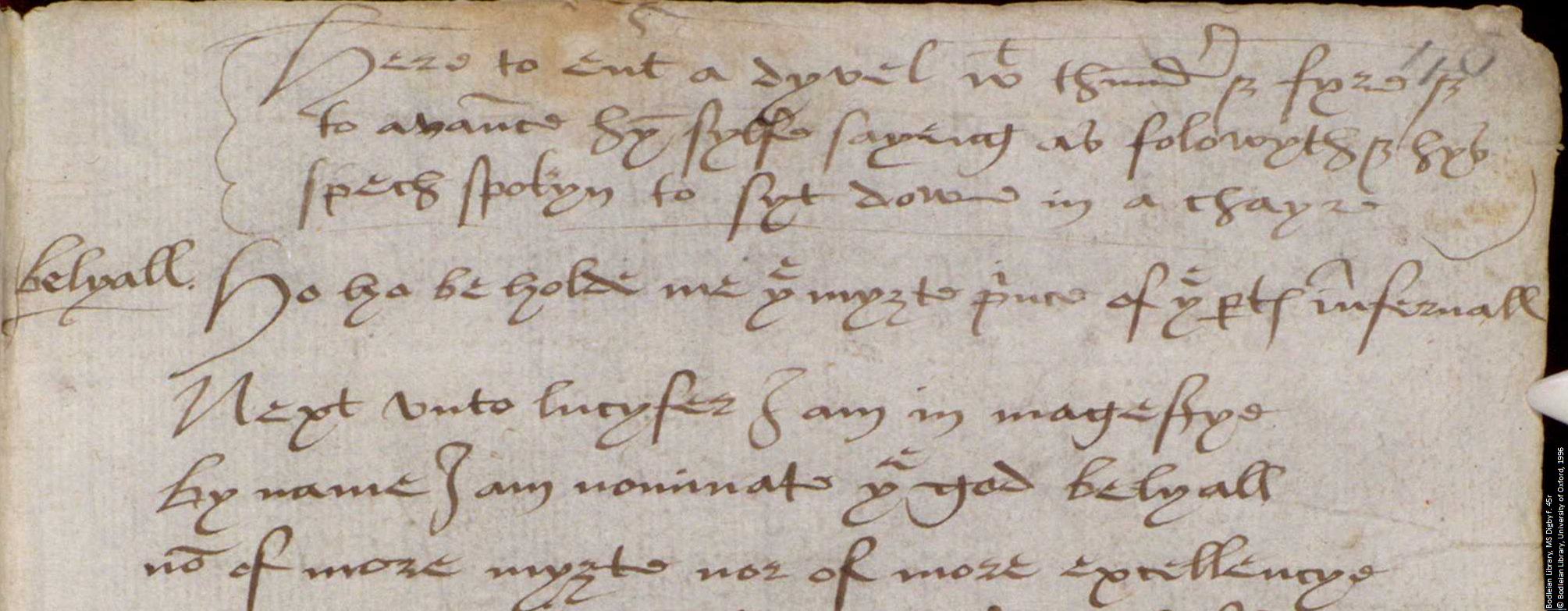

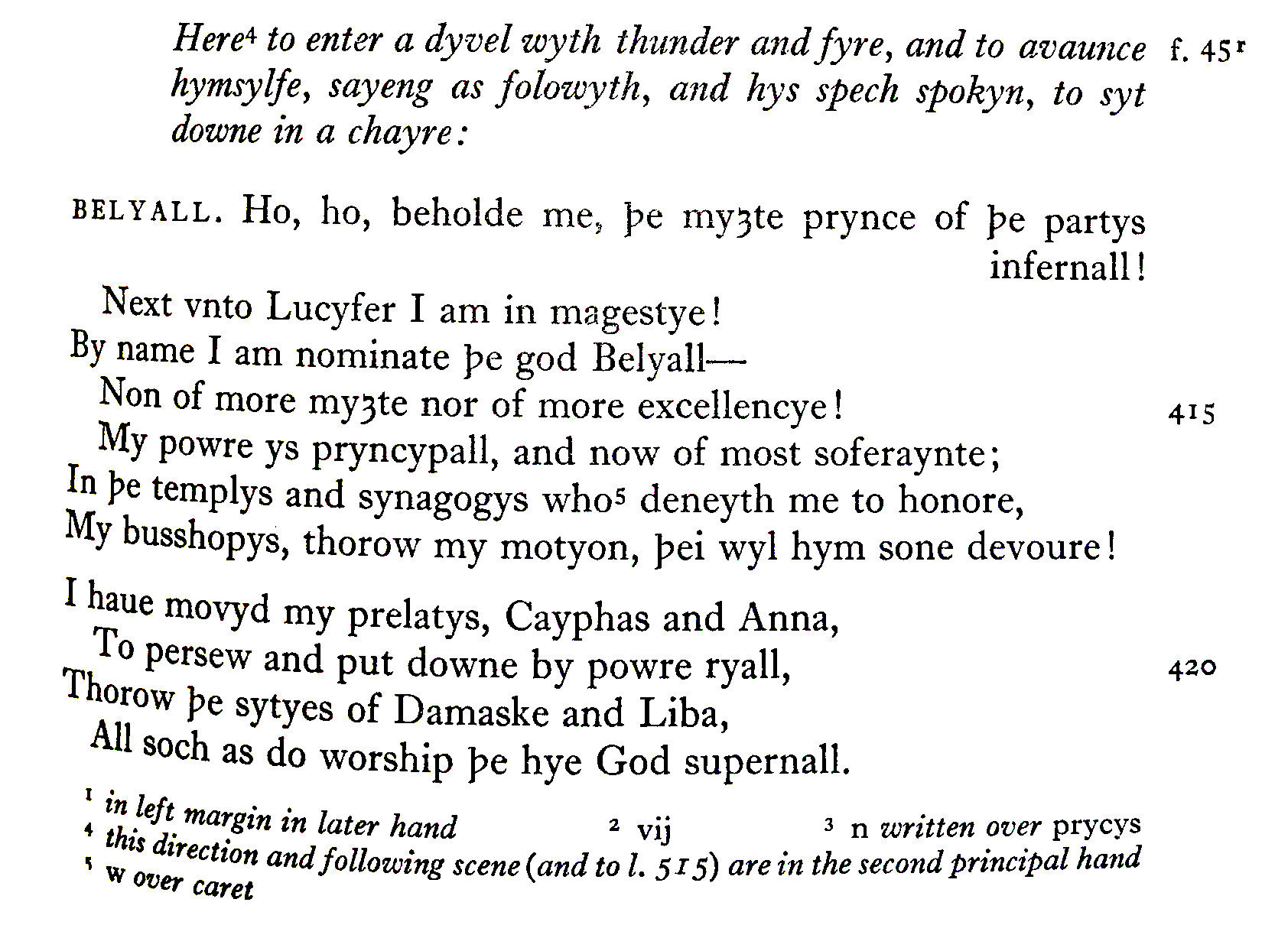

- Source: Bodleian MS Digby 133, f.45r, The Conversion of St Paul

- Language: Middle English Play, late-15thC, East Anglian

- Plot: The conversion of Saint Paul, from being Saul a persecutor of Christians to Paul a disciple of Jesus

- Added fun: there is a contemporary interpolation of 3 folios containing a devil's scene.

- Staging: Station-based but unclear, lots of theories including that audience moved from station to station

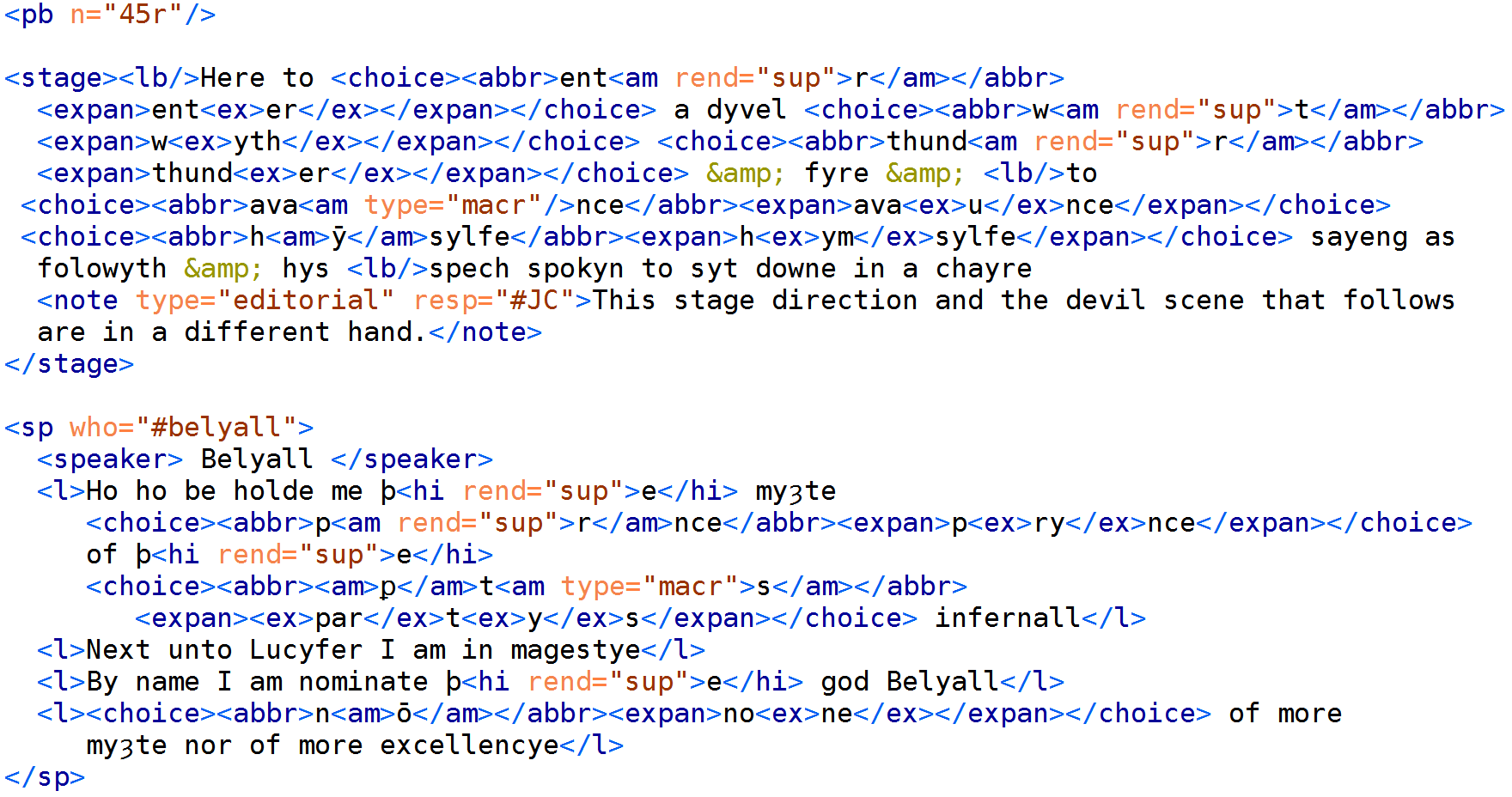

It isn't just that we want to record the abbreviations but also at least:

- what form the abbreviations took

- if we used a different editors reading for the expansion

- that this is all inside a stage direction

- that there has just been a folio break to f. 45r

- any editorial notes we have about this being an interpolated devil's scene by a different scribe

- that just after this a speech by the character Belyall starts

This uses <choice> with <abbr> (abbreviated word) and <expan> (expanded word) with <am> (abbreviation marker) and <ex> (expanded text); also <stage>, <note>, <sp>, <speaker>, <l>, <hi>, and others

Why add all this markup?

- Adding sufficient markup to create a scholarly digital edition enables many presentational benefits

- Not only can readers then trace back the precise editorial process in order to form their own conclusions ("You expanded that abbreviation wrong")

- But also the markup can be used to present different views on the same edition (Diplomatic, Edited, Reading, Acting, etc.)

- Users could toggle between individual abbreviations and expansions and we become less limited typographical signalling (italics, parentheses, font changes) for editorial changes

- It best represents the conceptual edited object (the edition as mental construct in the mind of the editor)

But wait, there is more...

It isn't just benefits for presentation that such markup provides but analysis as well. With it one could ask questions about:

- Consistency or not in our editing of particular forms (do we always include the superscript 't' of a 'wyth' abbreviation as part of the abbreviation marker or the existing text. (Useful if editing in teams...)

- Also enables analysis of:

- Word frequency or dialectical word forms of one part of the play to others (for example the interpolated devil's scene)

- use of markup over the whole text to generate aggregate reports on how we represent the text

- similar structures over multiple texts to find linguistic or stylometric patterns

Or even more...

- In studying the markup itself we can see how something has been marked up but crucially not why.

- In Newcastle we are starting to investigate editorial judgement, why editors make particular choices when faced with a specific editorial task.

- If we are able to get enough data (and indeed, having a large mass of data is our first stumbling blocks) then we are in the realm of data science

- An imagined future project will train machine learning algorithms to understand why editors make the decisions they do

- This would then enable AI assistants to editors, suggesting editorial interventions to them that they might want to make while editing a text

- Which could feed back into software, providing useful help

What do we need?

- In order to build a machine learning tool for scholarly editing, of course, we need a large corpus of editorial decisions

- In order to get a large corpus of editorial decisions we need lots of editors to use a single system (and/or find semi-automatic ways to categorise existing (printed) editorial decisions but that is problematic)

- In order to get a lot of editors to use a single system it would need to be providing them with useful outputs to encourage them to use it

- In order to have a popular system with useful outputs we need to make it so easy to use that editors do not mind having data tracked on how/why they make particular decisions while encoding their (possibly standoff) markup

- In order to have that, we need a system that is known to be stable, supported, sustainable, and future-proof. (Eeep!)

What kind of editors?

My example of the kind of scholarly editor I have in mind could be a vague stereotype that should work for any editor, but I also base it on people like my colleague the wonderful Professor Jenny Richards because she:

- Recognises as a 'traditional editor' that the digital is transformative for the field of scholarly editing

- Understands her technical limitations when it comes to learning things like TEI XML (she is our 'visionary luddite')

- But grasps the separation of the presentation of edited material from the intellectual tasks of editing

- Many 'traditional' editors get that far, but it is the learning of digital skills that keeps them from becoming digital editors

- Sure, she is also director of Newcastle's Humanities Research Institute and is deeply committed to interdisciplinary research

What should editors not learn?

For years I have said:

"It is easier to teach the subject specialist TEI than it is to teach a TEI expert another subject specialism".

This remains true, but for large scale adoption of an editing platform editors should not have to learn:

- XML (or any other particular structured data format) or editors for it: What is important is the categories of information used in a digital edition and then to have interfaces that create this for them.

- Virtual machine or server admin: Software should be hosted online (and also available in easy containerised packages for installation by local IT)

- Publication tools: Software should have easy outputs to standard formats (TEI/DOCX/HTML/PDF), modifying output should be straightforward

(Unless they want to of course!)

Why should a library care?

- Increasingly libraries are becoming the repositories of digital cultural outputs, and this includes scholarly digital editions

- While most scholarly digital editions are created in academic institutions, they often end up being hosted, supported, maintained, by institutional or national libraries

- In many ways it makes sense for libraries to curate these digital objects (especially when they are editions of analogue objects they hold) but ...

- ... we must recognise the need for ongoing resources to maintain them

- Edition-hosting institutions can only benefit from standardised hosting, creation, and publication of scholarly digital editions.

Dr James Cummings

Can We Make It Easier

To Do the Right Thing?

Infrastructure for digital scholarly editing

James.Cummings@newcastle.ac.uk

@jamescummings

CC+BY (press space to cycle through slides)