Back Propogation

How Calculus trains neural networks.

2025 James B. Wilson

https://slides.com/jameswilson-3/back-propogation/

What number am I thinking about?

- Choose a number between 1...100, keep is secret.

- Give clues of "Hot" or "Cold" to wrong guesses.

- Who in your group guesses correctly in fewest guesses?

This is a version of back propagation.

- You guess wildly.

- You learn the direction to travel next, and adjust.

- If someone include quantity to the direction "very hot", "super cold" you move faster.

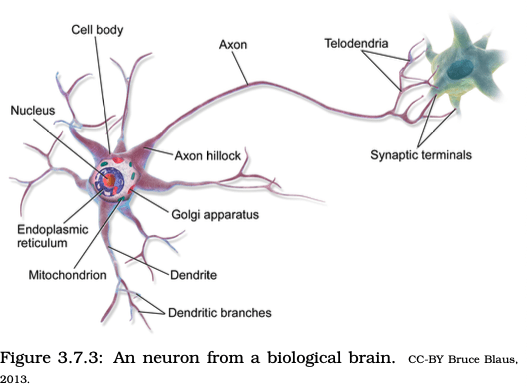

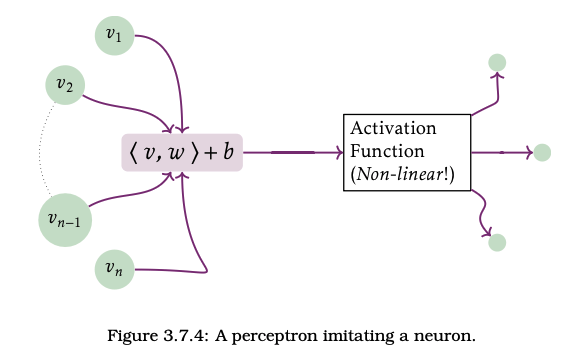

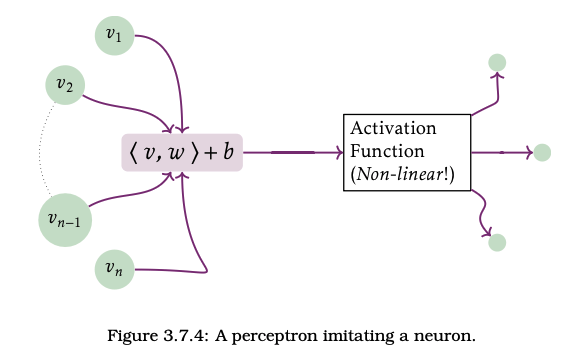

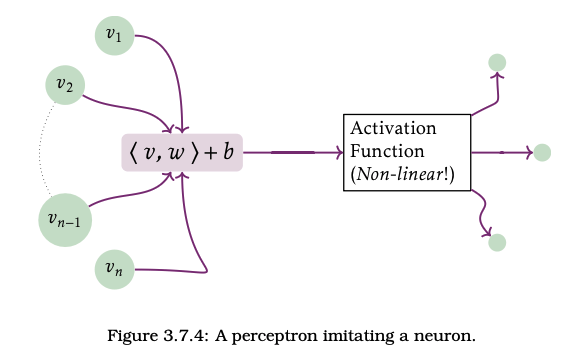

Imitating Life: make networks of neurons

CC-BY E.King & J. Wilson, Linear Data

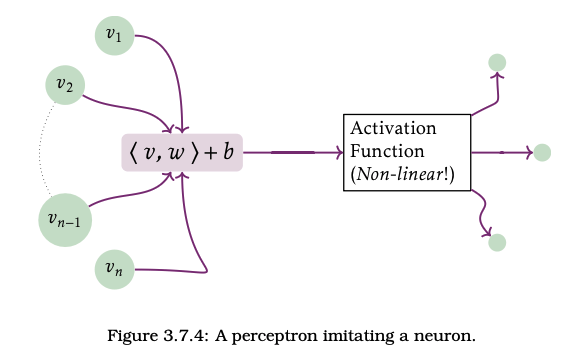

\[\langle v,w\rangle = \sum_i w_i v_i =\int v dw\]

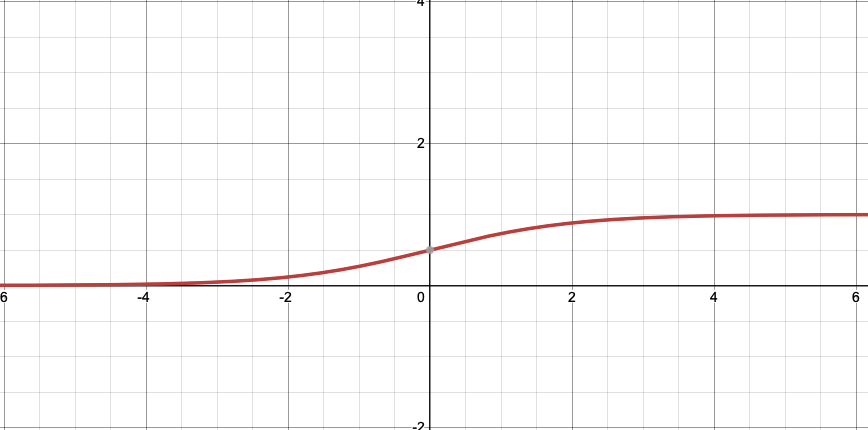

"ACTIVATION" Logistics/Sigmoid function

\[y=\frac{1}{1+e^{-x}}\qquad y'=y(1-y)\]

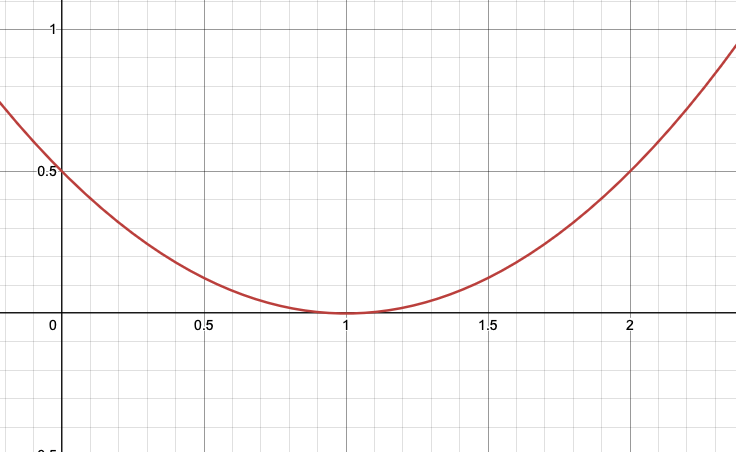

"Error" Least Square: penalize the extreems \[L(y_{fact},y_{comp})=\frac{1}{2}(y_{fact}-y_{comp})^2\]

\[\begin{aligned} f(v_1,v_2,v_3) &= y(w_1v_1+w_2v_2+w_3v_3+b)\\ &=\frac{1}{1+e^{-(w_1 v_1+w_2 v_2+w_3 v_3+b)}}\end{aligned}\]

Activate a perceptron "artificial neuron"

WARNING: This function is bounded between 0 and 1. So if you want to reach a number outside of [0,1] you will need to follow this activation function by a final layer that has a linear activation function that rescales to whatever you target.

Even so, you can seek to minimize the distance from 0,1.

\[\begin{aligned} f(x_1,x_2,x_3) &= y(w_1x_1+w_2x_2+w_3 x_3)\\ &=\frac{1}{1+e^{-(w_1 x_1+w_2 x_2+w_3 x_3)}}\end{aligned}\]

TRAINING a Perceptron "artificial neuron"

- Goal: Find \(w_1,w_2,w_3\)

- So that \(f(3,4,5)=0\pm \frac{1}{10^{10}}\)

What function has \(g(3,4,5)=0\)?

Could be loads! That is the point. You don't know and neither does the computer. All you told it was one point and now you want it to try and adjust one silly function \(f(x_1,x_2,x_3)\) to try and pretend to be \(g\). That this works can't depend on any deep learning. There simply isn't enough information given to "learn". .... but you and your machine could turn it into a guessing game and improve your odds.

By the way, \(g(a,b,c)=c^2-a^2-b^2\) was what I was thinking about.

\[\begin{aligned} f_w(v) &= y(wv)\\ &=\frac{1}{1+e^{-(w v) }}\end{aligned}\]

Train a perceptron "artificial neuron"

- Choose a \(w\)

- Compute \[y_w=f_w(3)\]

- Find the least-squares error \[L(0.2,y_w)=\frac{1}{2}(0.2-y_w)^2\]

- Now try to lower the error by choosing a new \(w\) and repeating the steps at least 3 times. Make a chart of you computations.

Sample Trail

- \(w=1\) so \[y_1:=f(3)=\frac{1}{1+e^{-(1\cdot 3)}}\approx 0.95\]

- Least squares error from the target point of 0.2 \[L(0.2,0.95)=\frac{1}{2}(0.2-0.95)^2\approx 0.28\]

- \(w=-1\) so \[y_{-1}:=f(3)=\frac{1}{1+e^{-((-1)\cdot 3)}}\approx 0.047\]

- Least squares error from the target point of 0.2 \[L(0.2,0.95)=\frac{1}{2}(0.2-0.047)^2\approx 0.012\]

Re-try with new \(w\)

A strategy to improve the loss

- \(\frac{dL}{dw}\) means ___________________________________

- to adjust \[w_{new}=w_{now}-\alpha \frac{dL}{dw}\] for \(\alpha\) the learning rate (say 1/10).

- \[\frac{d\sigma}{dz}=\sigma(z)(1-\sigma(z))\]

- Chain Rule

Knowing this go back and recompute you're weight.

Rate of change of L as function of \(w\)

\[\frac{d L}{dw}=\frac{dL}{d\sigma}\frac{d\sigma}{dy}\frac{dy}{dw}\]

- \(w=1\) so \[y_1:=f(3)=\frac{1}{1+e^{-(1\cdot 3)}}\approx 0.95\]

- Least squares error from the target point of 0.2 \[L(0.2,0.95)=\frac{1}{2}(0.2-0.95)^2\approx 0.28\]

- Compute

- \(w_{now}-\alpha\frac{dL}{dw}=1-\alpha\cdot (-0.11)=1-\frac{1}{2}(-0.11)=0.79\)

- \(w=0.79\) so \[y_{0.79}:=f(3)=\frac{1}{1+e^{-(0.79\cdot 3)}}\approx 0.91\]

- Least squares error from the target point of 0.2 \[L(0.2,0.91)=\frac{1}{2}(0.2-0.91)^2\approx 0.25\]