Lecture 12:

The Density Theorem and applications

Applying the Archimedian Property

Example. Show that \(\displaystyle{\inf\left\{\frac{1}{n^2+1} : n\in\N\right\} = 0}\).

Since \(\frac{1}{n^2+1}>0\) for all \(n\in\N\), it is clear that \(0\) is a lower bound for the set \[A:=\left\{\frac{1}{n^2+1} : n\in\N\right\}.\]

Suppose \(x>0\). We must show that \(x\) is not a lower bound for \(A\).

Problem: \(\frac{x}{2}\) might not be in the set \(A\).

So we want to find \(m\in\N\) so that

\(\displaystyle{\frac{1}{m^2+1}<x}\)

\[\Leftrightarrow \frac{1}{x}<m^2+1\]

Notice that \(m^2+1>m\) for \(m\in\N\), and hence it would be good enough to find \(m\in\N\) such that \(m>\frac{1}{x}\).

Applying the Archimedian Property

Example. Show that \(\displaystyle{\inf\left\{\frac{1}{n^2+1} : n\in\N\right\} = 0}\).

Since \(\frac{1}{n^2+1}>0\) for all \(n\in\N\), it is clear that \(0\) is a lower bound for the set \[A:=\left\{\frac{1}{n^2+1} : n\in\N\right\}.\]

Suppose \(x>0\). We must show that \(x\) is not a lower bound for \(A\).

By the Archimedian Property there is a number \(m\in\N\) such that \(m>\frac{1}{x}\). Since \(m\geq 1\) we see that \(m^2+1>m^2\geq m\), and hence \(m^2+1>\frac{1}{x}\). Rearranging this inequality we see that

\[x>\frac{1}{m^2+1}.\]

Since \(\frac{1}{m^2+1}\in A\), we see that \(x\) is not a lower bound for \(A\). Therefore, \(0\) is the greatest lower bound for \(A\).

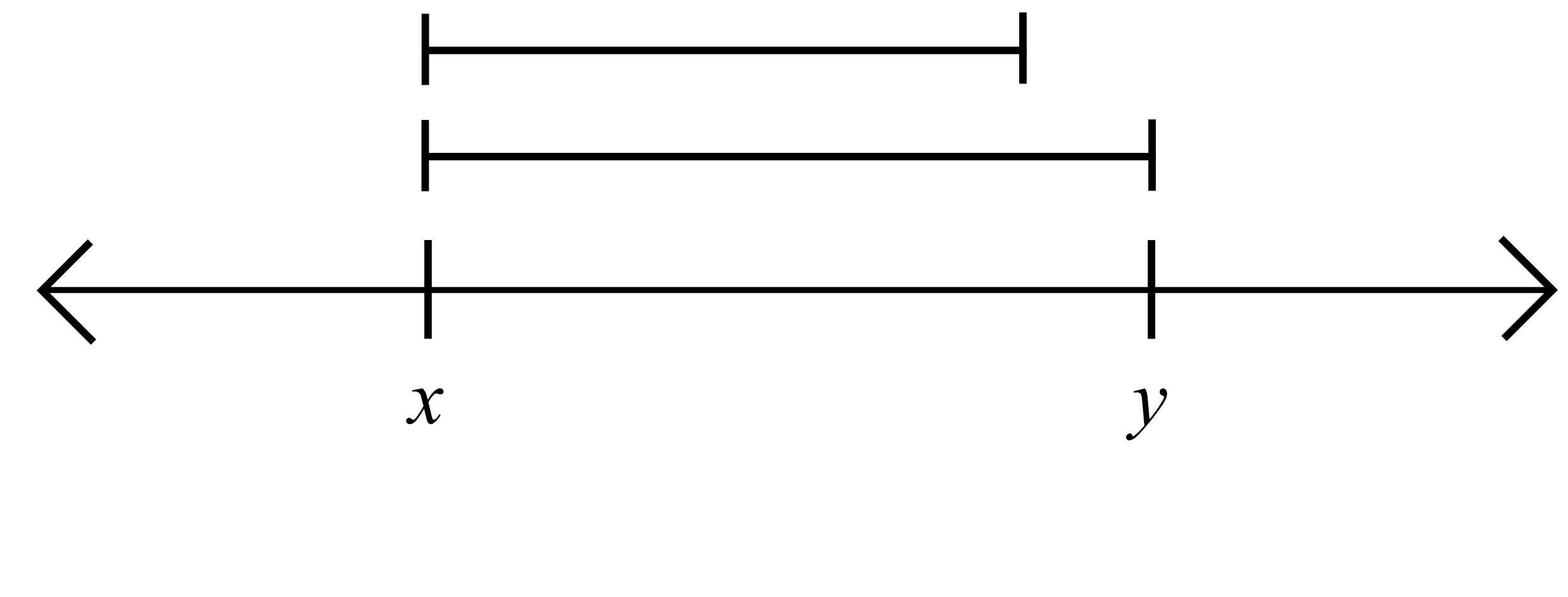

Theorem (the Density Theorem). If \(x\) and \(y\) are real numbers, and \(x<y\), then there exists a rational number \(r\in\mathbb{Q}\) such that \(x<r<y\).

\(y-x\)

Find \(n\in\N\) so that \(y-x>\frac{1}{n}\)

\[\frac{1}{n}\]

Theorem (the Density Theorem). If \(x\) and \(y\) are real numbers, and \(x<y\), then there exists a rational number \(r\in\mathbb{Q}\) such that \(x<r<y\).

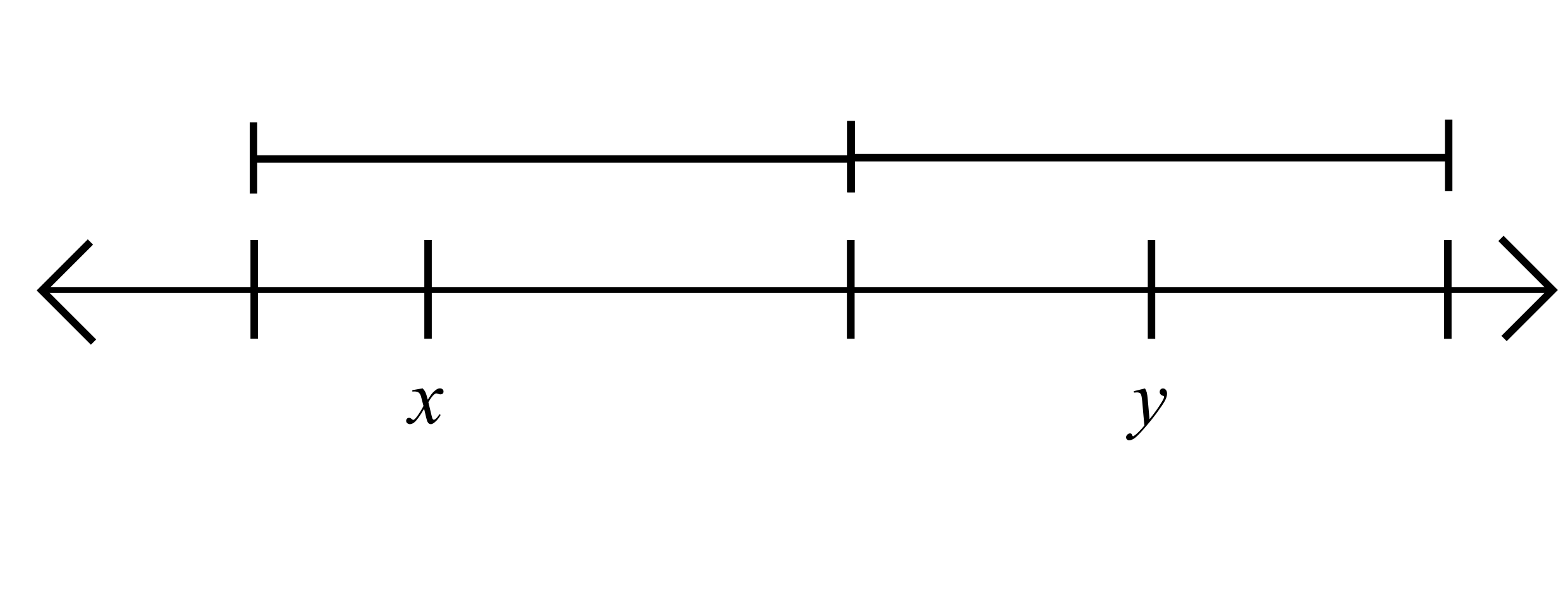

Find \(n\in\N\) so that \(y-x>\frac{1}{n}.\)

Since \(y-x>\frac{1}{n}\) there is an \(m\in\Z\) such that \(x<\frac{m}{n}<y.\)

\[\frac{1}{n}\]

\[\frac{1}{n}\]

\[\frac{m-1}{n}\]

\[\frac{m}{n}\]

\[\frac{m+1}{n}\]

The Density Theorem

Theorem 2.4.8 (The Density Theorem) If \(x\) and \(y\) are real numbers with \(x<y\), then there exists a rational number \(r\in\mathbb{Q}\) such that \[x<r<y.\]

Proof. We will do two cases. First assume \(x>0\).

By the Archimedean Property there is a number \(n\in\N\) such that \[n>\frac{1}{y-x}.\] This implies that \(nx+1<ny\). Let \(m\) be the smallest natural number such that \(m>nx\). Since \(m\) is minimal, we must have \(m-1\leq nx\), and hence \(m\leq nx+1\). We conclude that \(nx<m\leq nx+1<ny\).

Multiplying by \(\frac{1}{n}\) we have

\[x<\frac{m}{n}<y.\]

This completes the proof under the assumption that \(x>0\).

The Density Theorem

Theorem 2.4.8 (The Density Theorem) If \(x\) and \(y\) are real numbers with \(x<y\), then there exists a rational number \(r\in\mathbb{Q}\) such that \[x<r<y.\]

Proof continued. Now, we assume \(x\leq 0\). By the Archimedean Property there exists \(k\in\N\) such that \(k>-x\). Set \(x'=x+k\) and \(y'=y+k\). The assumption that \(x<y\) implies \[x'=x+k<y+k=y'.\]

Note that \(k>-x\) implies \(x'>0\). So, by the first part of the proof there is a rational number \(r\in\mathbb{Q}\) such that \(x'<r<y'\). Subtracting \(k\) we have

\[x<r-k<y.\]

Since \(r-k\in\mathbb{Q}\), this completes the proof. \(\Box\)

Example. Show that \(\inf\{r\in\mathbb{Q} : 2<r\leq 4\} = 2\).

Proof. Set

\[R = \{r\in\mathbb{Q} : 2<r\leq 4\}.\]

It is clear from the definition that \(2\) is a lower bound for \(R\). Let \(x>2\) be arbitrary. We will consider two cases.

Case 1. Suppose \(x<4\). By the Density Theorem there is a rational number \(r\in\mathbb{Q}\) so that \(2<r<x\). We see that \(r\in R\), and thus \(x\) is not a lower bound for \(R\).

Case 2. Suppose \(x\geq 4\). In this case we have \(3\leq x\). Since \(3\in R\), this shows that \(x\) is not a lower bound for \(R\).

Thus, \(2\) is a lower bound for \(R\), and any \(x>2\) is not a lower bound for \(R\). Therefore \(2\) the the greatest lower bound for \(R\). \(\Box\)

Practice problem.

Show that \(\sup\{r\in\mathbb{Q} : r<\pi\} = \pi\).

End Lecture 12

Proof. Set

\[P = \{r\in\mathbb{Q} : r<\pi\}.\]

It is clear from the definition that \(\pi\) is an upper bound for \(P\). Let \(x<\pi\) be arbitrary. By the Density Theorem there is a rational number \(r\in\mathbb{Q}\) so that \(x<r<\pi\). Since \(r\in P\), this shows that \(x\) is not an upper bound for \(P\).

Thus, \(pi\) is an upper bound for \(S\), and any \(x<\pi\) is not an upper bound for \(P\). Therefore \(\pi\) the the least upper bound for \(P\). \(\Box\)