Lecture 2:

Manipulating inequalities

Proposition 2. If \(a>b\) and \(c\in\R\), then \(a+c>b+c\).

Proposition 3. If \(a>b\) and \(c>0\), then \(ac>bc\).

How do we use Propositions 2 and 3?

Let's say we know that \(x\) is a number such that \(x>4\).

From Proposition \(2\) we see that \(x-1>3\).

From Proposition \(3\) we see that \(2x-2>6\).

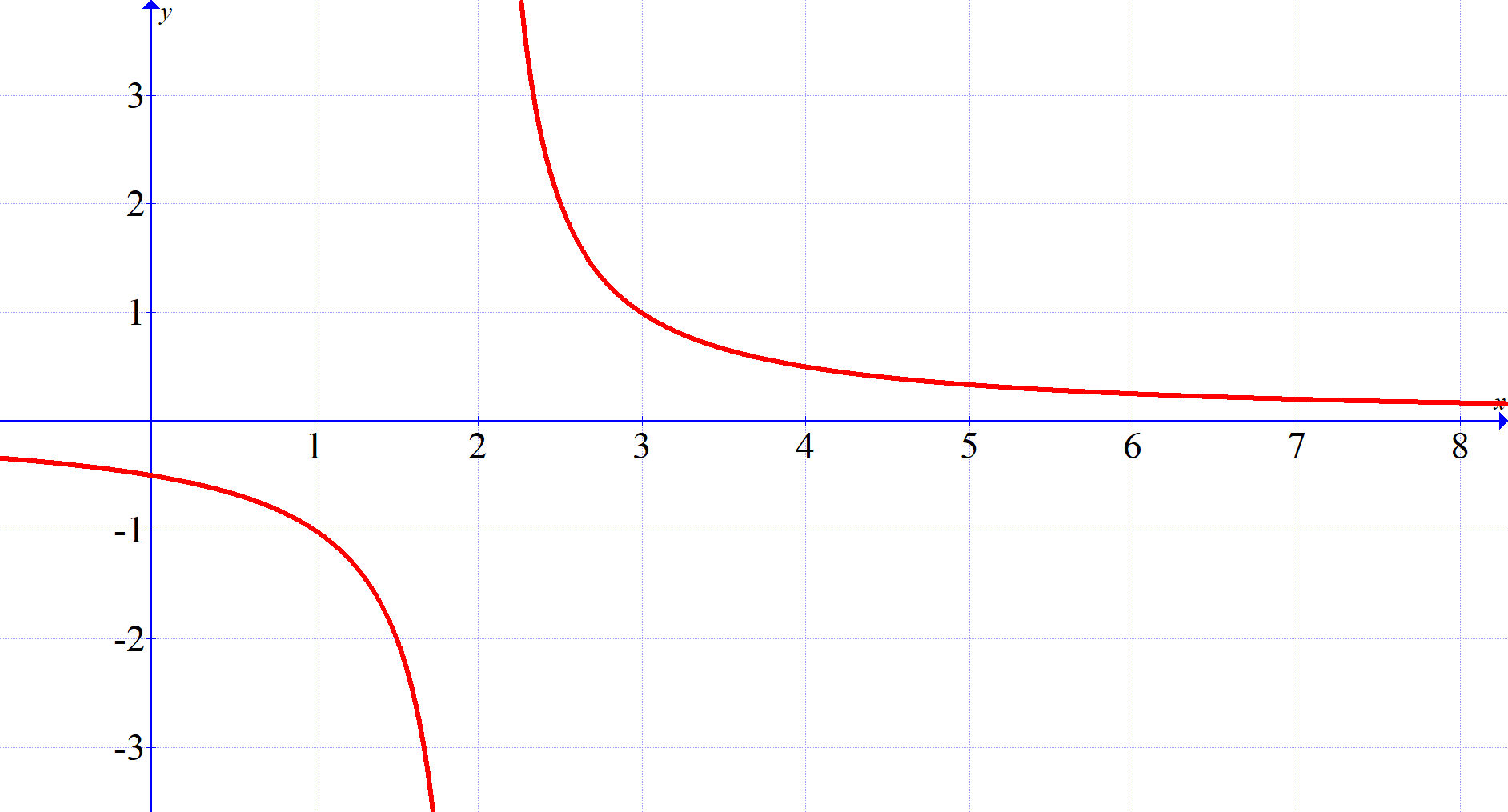

If \(x\) is a real number such that \(-1<x<3\), then what can we say about the number \(3x-5\)?

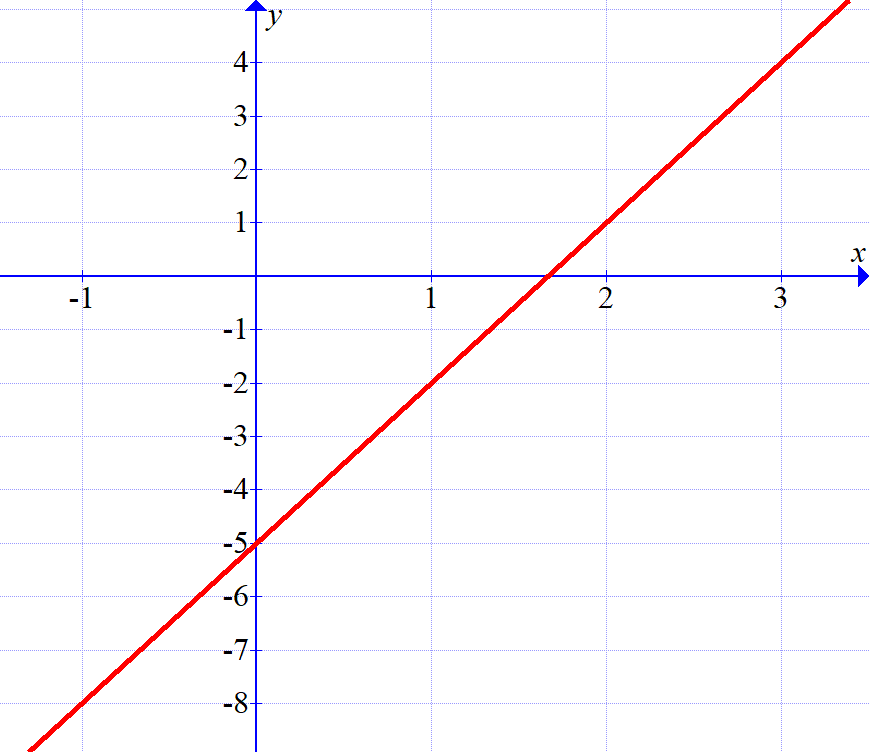

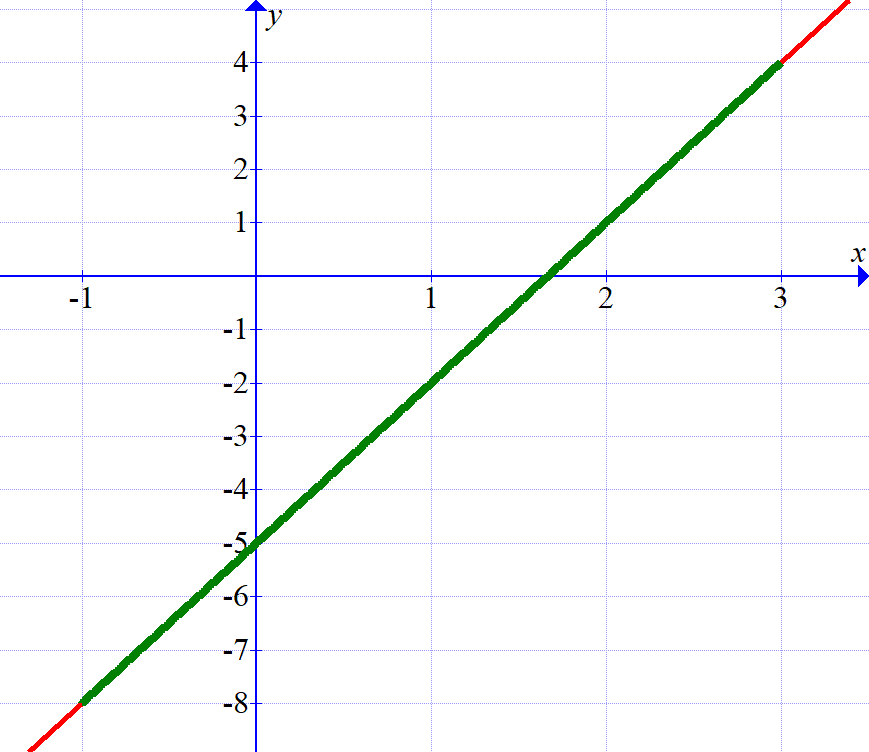

\(y=3x-5\)

From the picture, it appears that \(-8<3x-5<4\), but how do we prove it?

Proposition. If \(-1<x<3\), then \(-8<3x-5<4\).

Proof. Assume \(-1<x<3\). From the assumption that \(x>-1\) we see that \(3x>-3\), and hence \(3x-5>-8\). From the assumption that \(x<3\) we see that \(3x<9\), and hence \(3x-5<4\). Putting these together we obtain

\[-8<3x-5<4.\ \Box\]

These last two propositions do most of what we need when working with inequalities:

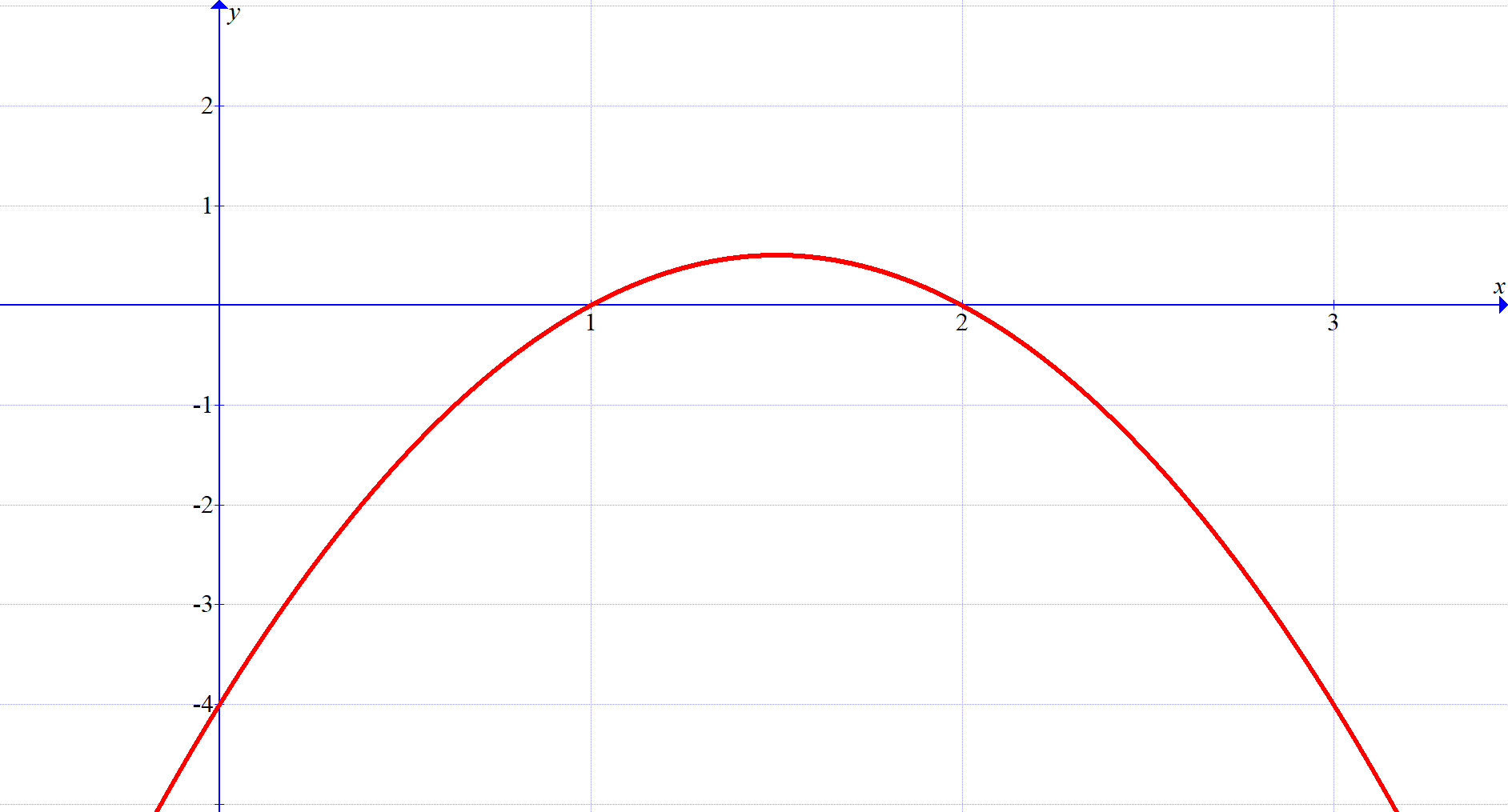

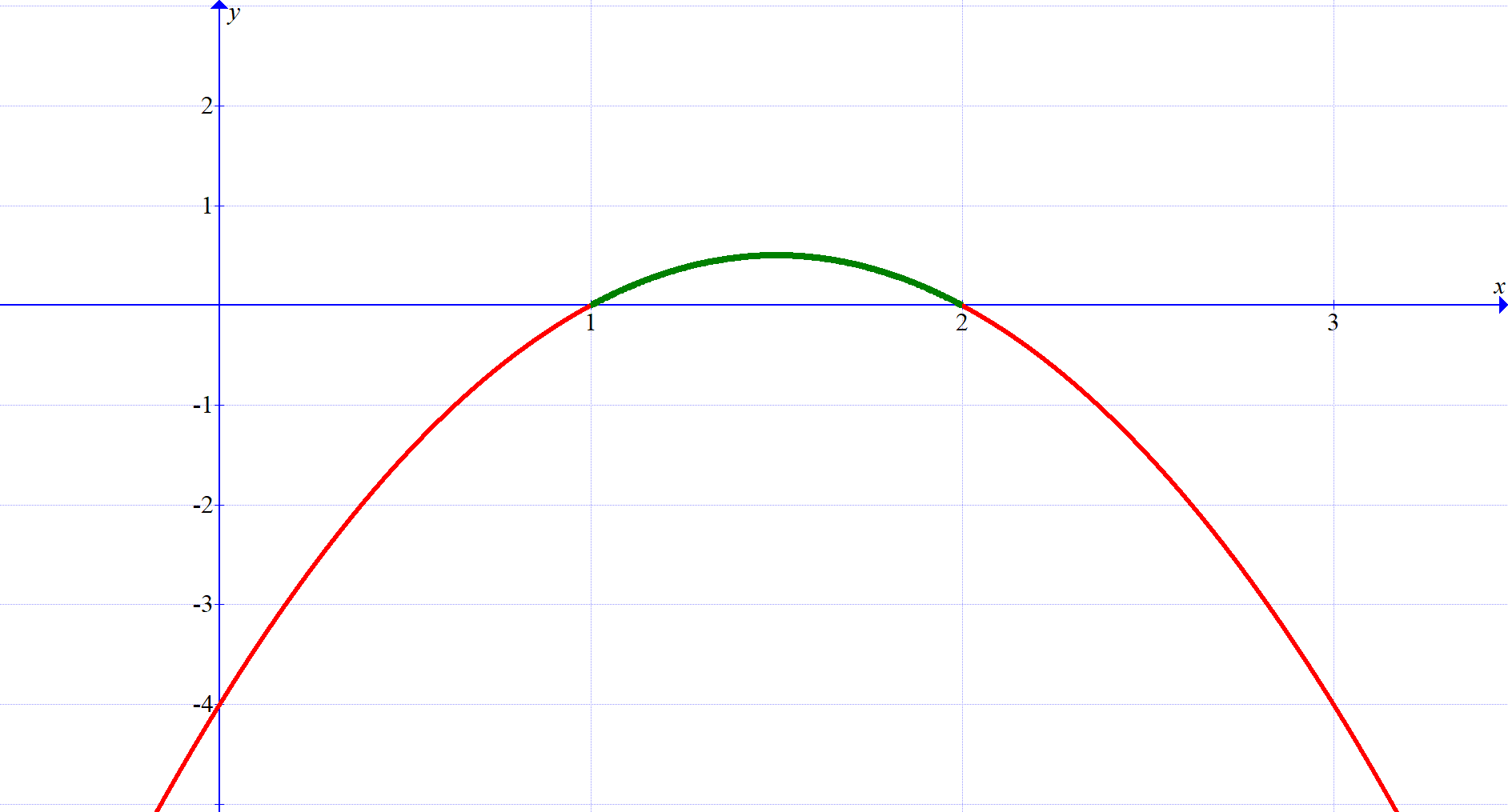

Here is an example: Assume \(1<x<2\). How small can \(-2x^2+2x-4\) be?

\(y=-2x^2+2x-4\)

Here is an example: Assume \(1<x<2\). How small can \(-2x^2+2x-4\) be?

\[x>1\quad\Rightarrow\quad 2x>2\quad\text{multiplying both sides by } 2\]

\[\quad\Rightarrow\quad 2x-2>0\quad\text{adding \(-2\) to both sides}\]

\[x<2\quad\Rightarrow\quad 0<2-x\quad\text{adding \(-x\) to both sides}\]

Putting these two inequalities together we have

\[2x-2>0\quad\text{and}\quad2-x>0\quad\Rightarrow\quad (2x-2)(2-x)>0\]

since positive numbers are closed under multiplication.

Multiplying this out we see that

\[-2x^2+2x-4>0.\]

A common pitfall

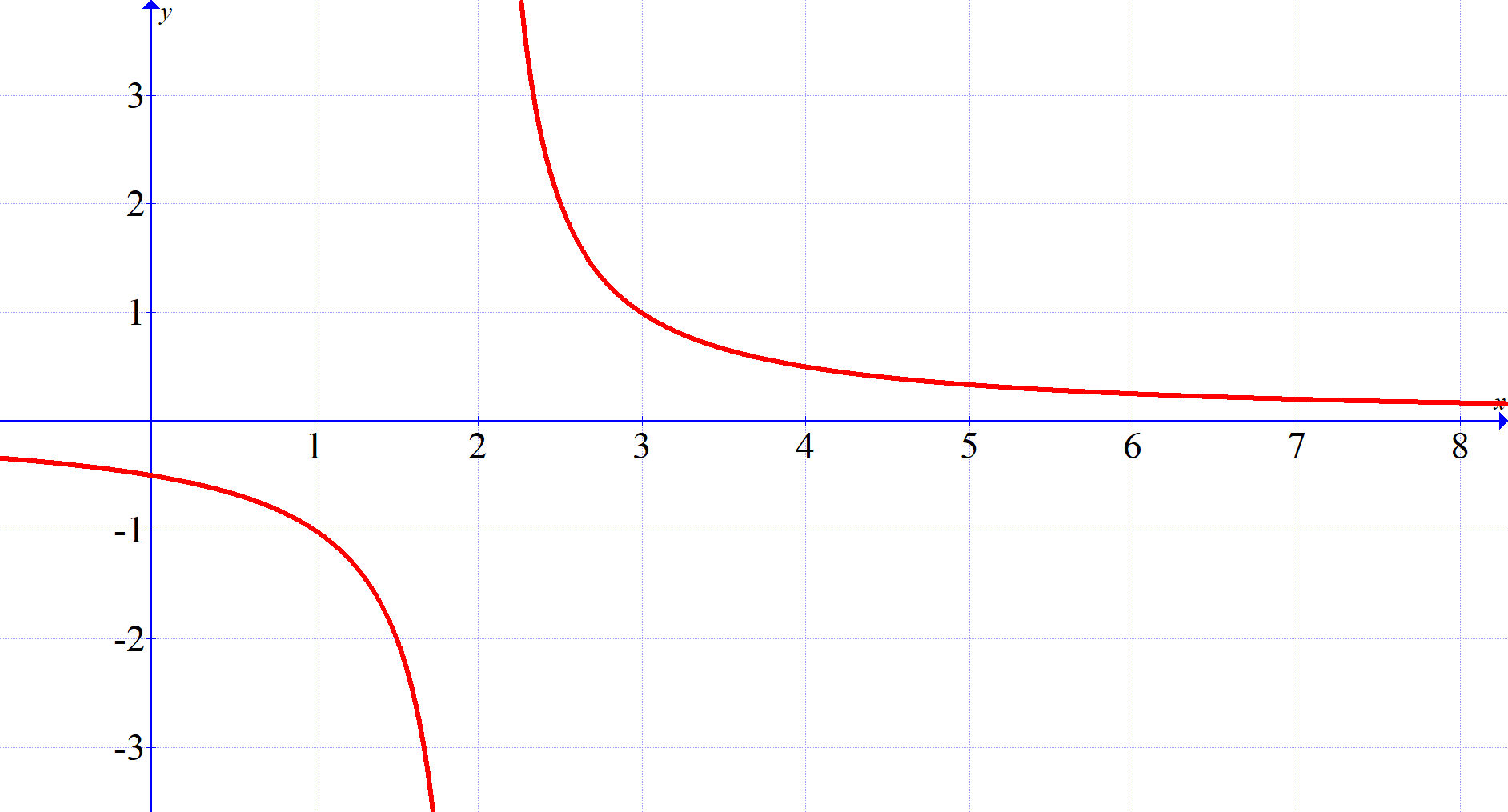

Assume \(x>5\). What can we say about \(\dfrac{1}{x-2}\)?

\[x>5\quad\Rightarrow\quad x-2>3\quad\text{adding \(-2\) to both sides}\]

\[\quad\Rightarrow\quad \frac{1}{x-2}>\frac{1}{3}\quad\text{taking the reciprocal of both sides}\]

\(y=\dfrac{1}{x-2}\)

A common pitfall (avoided)

Assume \(x>5\). What can we say about \(\dfrac{1}{x-2}\)?

\[x>5\quad\Rightarrow\quad x-2>3\quad\text{adding \(-2\) to both sides}\]

\[x-2>3\quad\Rightarrow\quad 1>\frac{3}{x-2}\quad\text{multiplying both sides by } \frac{1}{x-2}\]

From this we see that \(x-2\) is positive, and hence so is \(\frac{1}{x-2}\) (why?).

Finally, we multiply both sides by \(\frac{1}{3}\) and we see that

\[\frac{1}{3}>\frac{1}{x-2}\]

A common pitfall (avoided)

\[\frac{1}{3}>\frac{1}{x-2}\]

\(y=\dfrac{1}{x-2}\)

Prove the following:

If \(x<3\), then \(\dfrac{2}{4-x}<2\).

Proof. Assume \(x<3\). Adding \(-x\) we obtain \(0<3-x\). Adding \(1\) we see that \(4-x>1\). Note that \(4-x\) is positive, and hence \(\frac{1}{4-x}\) is also positive. Multiplying both sides of \(4-x>1\) by \(\frac{1}{4-x}\) we see that

\[1>\frac{1}{4-x}.\]

Finally, multiplying by \(2\) yields

\[2>\frac{2}{4-x}\]

as desired. \(\Box\)