Lecture 23:

The monotone convergence theorem

Theorem (Monotone Convergence Theorem). A monotone sequence is convergent if and only if it is bounded. Further:

- If \(X = (x_{n})\) is a bounded increasing sequence, then \[\lim(x_{n}) = \sup\{x_{n} : n\in\N\}.\]

- If \(Y=(y_{n})\) is a bounded decreasing sequence, then \[\lim(y_{n}) = \inf\{y_{n} : n\in\N\}.\]

Theorem (Monotone Convergence Theorem). A monotone sequence is convergent if and only if it is bounded. Further:

- If \(X = (x_{n})\) is a bounded increasing sequence, then \[\lim(x_{n}) = \sup\{x_{n} : n\in\N\}.\]

- If \(Y=(y_{n})\) is a bounded decreasing sequence, then \[\lim(y_{n}) = \inf\{y_{n} : n\in\N\}.\]

Proof. We have already proved that a convergent sequence is bounded (Theorem 3.2.2 in the text). The proves the forward direction.

Theorem (Monotone Convergence Theorem). A monotone sequence is convergent if and only if it is bounded. Further:

- If \(X = (x_{n})\) is a bounded increasing sequence, then \[\lim(x_{n}) = \sup\{x_{n} : n\in\N\}.\]

- If \(Y=(y_{n})\) is a bounded decreasing sequence, then \[\lim(y_{n}) = \inf\{y_{n} : n\in\N\}.\]

Proof. We have already proved that a convergent sequence is bounded (Theorem 3.2.2 in the text). The proves the forward direction.

Suppose \((x_{n})\) is a bounded monotone sequence. There are two cases to consider:

Theorem (Monotone Convergence Theorem). A monotone sequence is convergent if and only if it is bounded. Further:

- If \(X = (x_{n})\) is a bounded increasing sequence, then \[\lim(x_{n}) = \sup\{x_{n} : n\in\N\}.\]

- If \(Y=(y_{n})\) is a bounded decreasing sequence, then \[\lim(y_{n}) = \inf\{y_{n} : n\in\N\}.\]

Proof. We have already proved that a convergent sequence is bounded (Theorem 3.2.2 in the text). The proves the forward direction.

Suppose \((x_{n})\) is a bounded monotone sequence. There are two cases to consider:

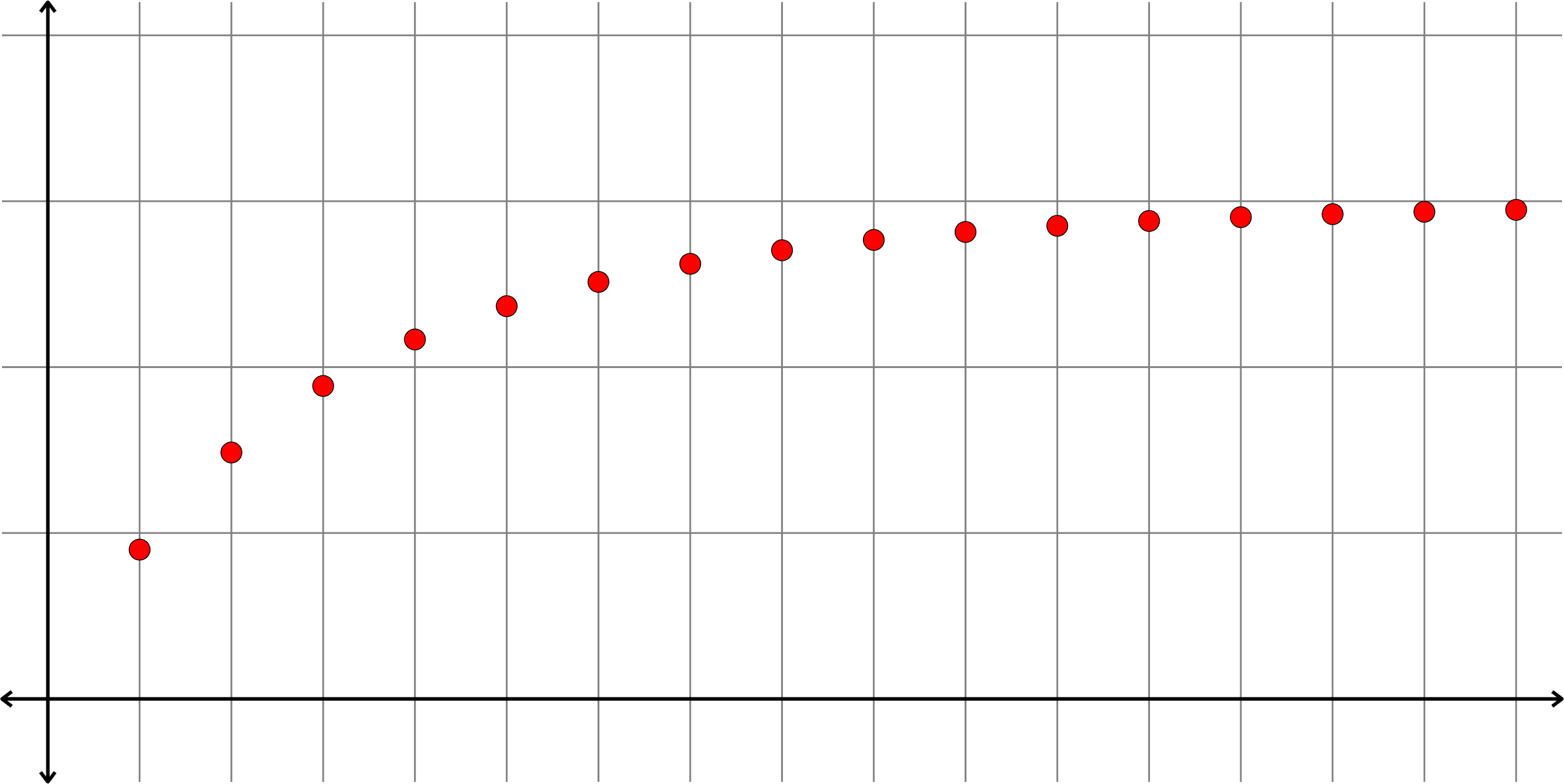

Case 1: Suppose \((x_{n})\) is increasing.

Theorem (Monotone Convergence Theorem). A monotone sequence is convergent if and only if it is bounded. Further:

- If \(X = (x_{n})\) is a bounded increasing sequence, then \[\lim(x_{n}) = \sup\{x_{n} : n\in\N\}.\]

- If \(Y=(y_{n})\) is a bounded decreasing sequence, then \[\lim(y_{n}) = \inf\{y_{n} : n\in\N\}.\]

Proof. We have already proved that a convergent sequence is bounded (Theorem 3.2.2 in the text). The proves the forward direction.

Suppose \((x_{n})\) is a bounded monotone sequence. There are two cases to consider:

Case 1: Suppose \((x_{n})\) is increasing. Since \((x_{n})\) is bounded, and in particular, bounded above, there is a number \(M\) such that

\[x_{n}\leq M\text{ for all }n\in\N.\]

Theorem (Monotone Convergence Theorem). A monotone sequence is convergent if and only if it is bounded. Further:

- If \(X = (x_{n})\) is a bounded increasing sequence, then \[\lim(x_{n}) = \sup\{x_{n} : n\in\N\}.\]

- If \(Y=(y_{n})\) is a bounded decreasing sequence, then \[\lim(y_{n}) = \inf\{y_{n} : n\in\N\}.\]

Proof. We have already proved that a convergent sequence is bounded (Theorem 3.2.2 in the text). The proves the forward direction.

Suppose \((x_{n})\) is a bounded monotone sequence. There are two cases to consider:

Case 1: Suppose \((x_{n})\) is increasing. Since \((x_{n})\) is bounded, and in particular, bounded above, there is a number \(M\) such that

\[x_{n}\leq M\text{ for all }n\in\N.\]

Thus, \(M\) is an upper bound for the set \(\{x_{n} : n\in\N\}\). By the completeness property of \(\R\) this set has a supremum, call it \(x^{\ast}\).

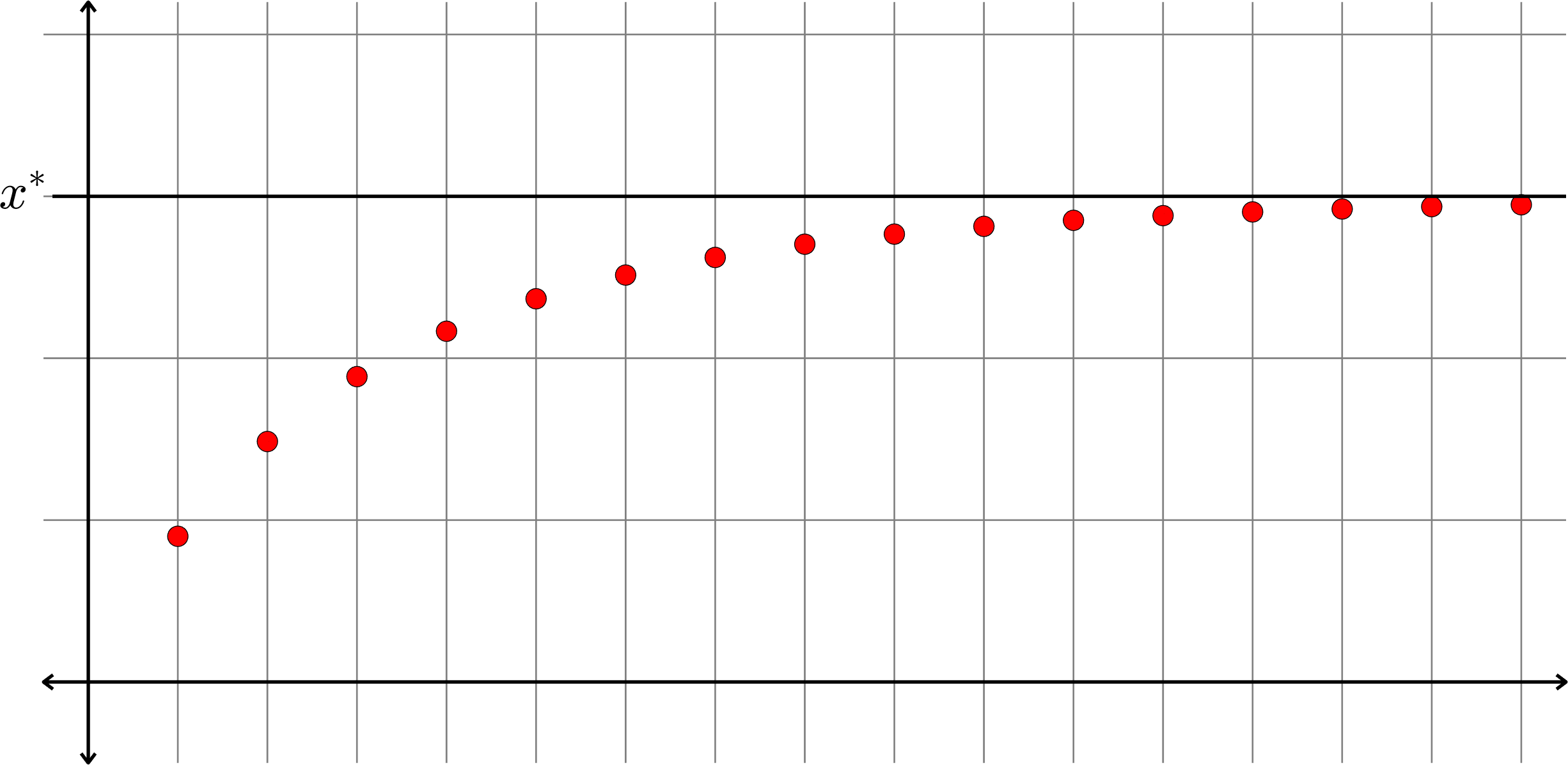

Proof continued. We wish to show that \(\lim(x_{n}) = x^{\ast}.\)

Proof continued. We wish to show that \(\lim(x_{n}) = x^{\ast}.\) Let \(\varepsilon>0\) be given.

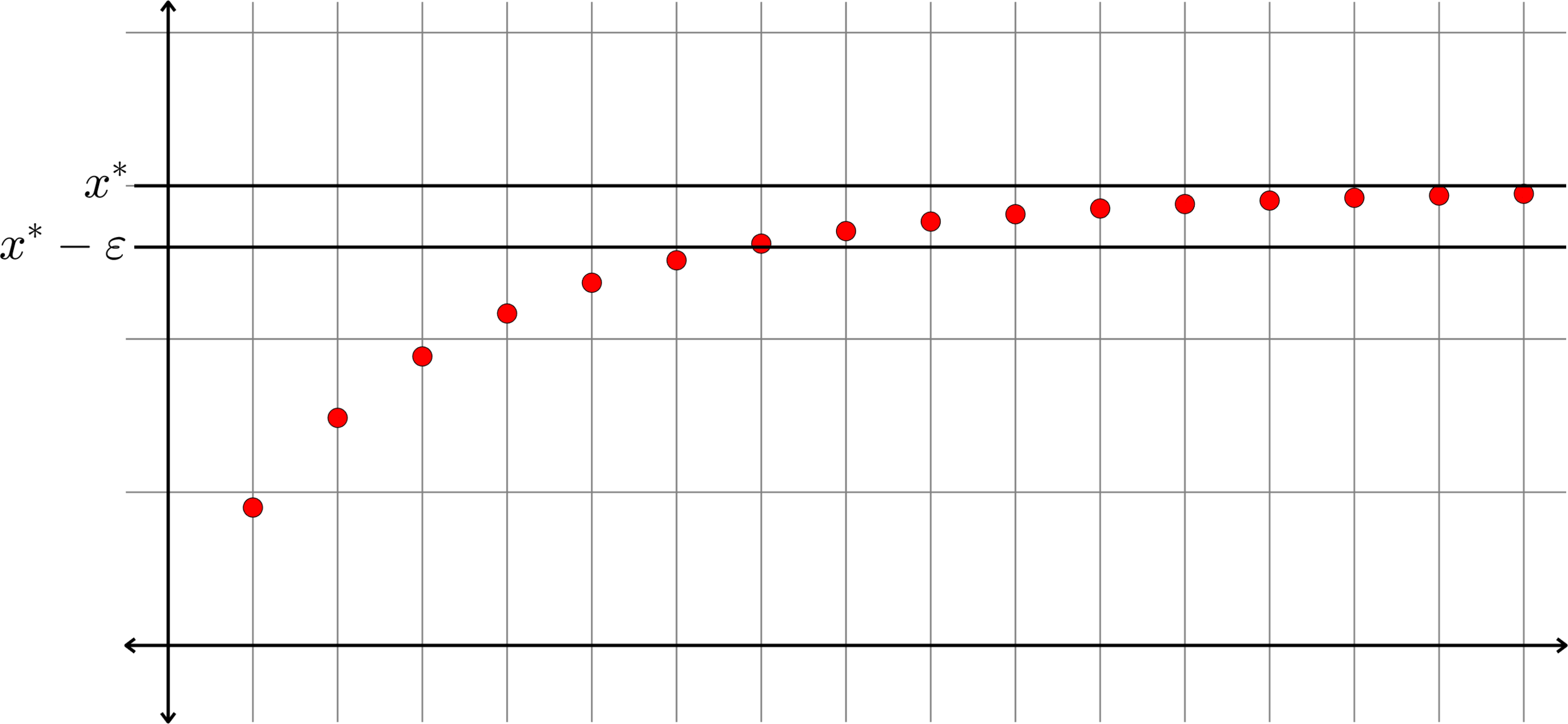

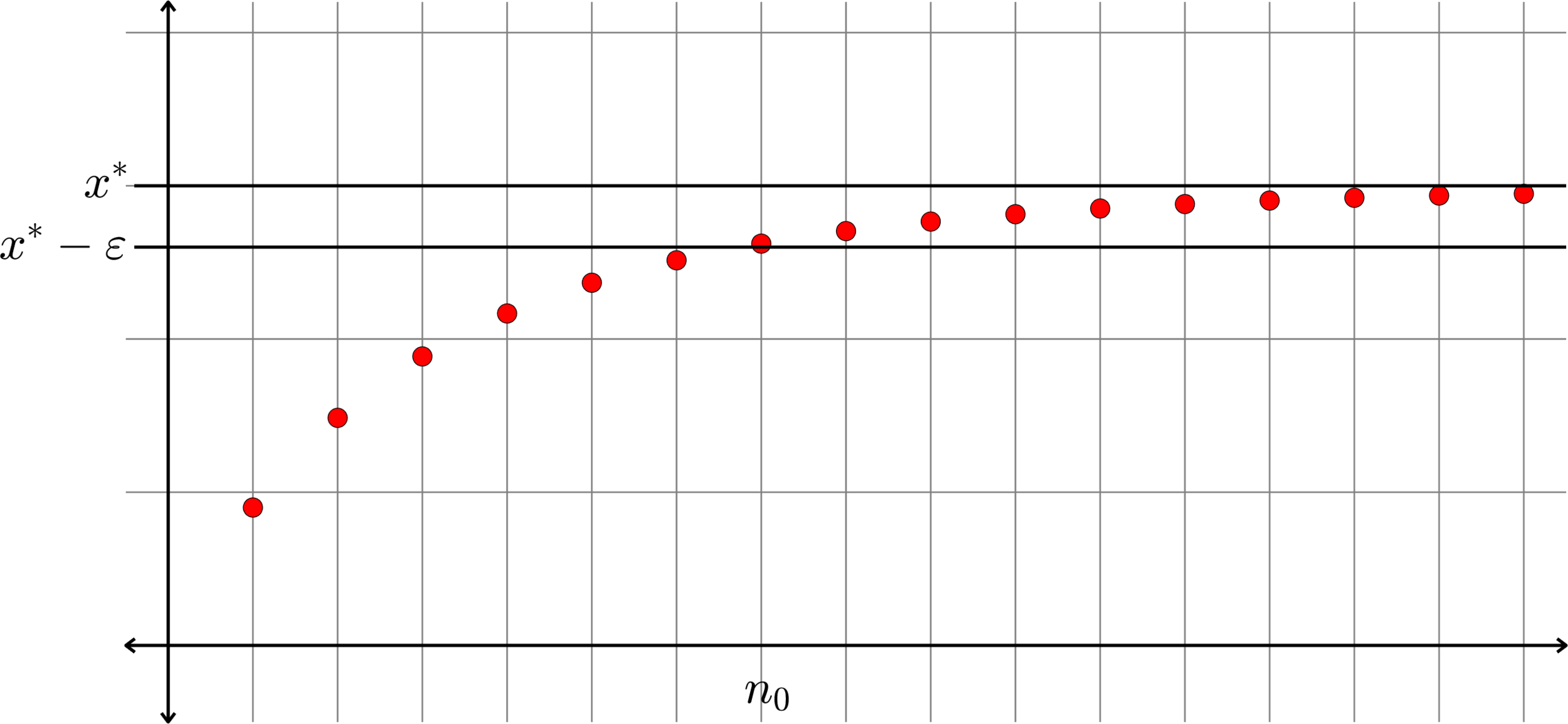

Proof continued. We wish to show that \(\lim(x_{n}) = x^{\ast}.\) Let \(\varepsilon>0\) be given. By the definition of the least upper bound, the number \(x^{\ast}-\varepsilon\) is not an upper bound for \(\{x_{n} : n\in\N\}\). That is, there is some \(n_{0}\in\N\) such that \(x_{n_{0}}>x^{\ast} - \varepsilon\).

Proof continued. We wish to show that \(\lim(x_{n}) = x^{\ast}.\) Let \(\varepsilon>0\) be given. By the definition of the least upper bound, the number \(x^{\ast}-\varepsilon\) is not an upper bound for \(\{x_{n} : n\in\N\}\). That is, there is some \(n_{0}\in\N\) such that \(x_{n_{0}}>x^{\ast} - \varepsilon\). Because of our assumption that \((x_{n})\) is increasing, if \(n\geq n_{0}\) then \(x_{n}\geq x_{n_{0}}>x^{\ast} - \varepsilon.\)

Proof continued. We wish to show that \(\lim(x_{n}) = x^{\ast}.\) Let \(\varepsilon>0\) be given. By the definition of the least upper bound, the number \(x^{\ast}-\varepsilon\) is not an upper bound for \(\{x_{n} : n\in\N\}\). That is, there is some \(n_{0}\in\N\) such that \(x_{n_{0}}>x^{\ast} - \varepsilon\). Because of our assumption that \((x_{n})\) is increasing, if \(n\geq n_{0}\) then \(x_{n}\geq x_{n_{0}}>x^{\ast} - \varepsilon.\) Rearranging, we have

\[x^{\ast} - x_{n}<\varepsilon\text{ for all }n\geq n_{0}.\]

Proof continued. We wish to show that \(\lim(x_{n}) = x^{\ast}.\) Let \(\varepsilon>0\) be given. By the definition of the least upper bound, the number \(x^{\ast}-\varepsilon\) is not an upper bound for \(\{x_{n} : n\in\N\}\). That is, there is some \(n_{0}\in\N\) such that \(x_{n_{0}}>x^{\ast} - \varepsilon\). Because of our assumption that \((x_{n})\) is increasing, if \(n\geq n_{0}\) then \(x_{n}\geq x_{n_{0}}>x^{\ast} - \varepsilon.\) Rearranging, we have

\[x^{\ast} - x_{n}<\varepsilon\text{ for all }n\geq n_{0}.\]

Since \(x^{\ast}\) is an upper bound for the set \(\{x_{n} : n\in\N\},\) we know that \(x^{\ast}\geq x_{n}\) for all \(n\in\N\). Therefore

\[|x^{\ast} - x_{n}|<\varepsilon\text{ for all }n\geq n_{0}.\]

Proof continued. We wish to show that \(\lim(x_{n}) = x^{\ast}.\) Let \(\varepsilon>0\) be given. By the definition of the least upper bound, the number \(x^{\ast}-\varepsilon\) is not an upper bound for \(\{x_{n} : n\in\N\}\). That is, there is some \(n_{0}\in\N\) such that \(x_{n_{0}}>x^{\ast} - \varepsilon\). Because of our assumption that \((x_{n})\) is increasing, if \(n\geq n_{0}\) then \(x_{n}\geq x_{n_{0}}>x^{\ast} - \varepsilon.\) Rearranging, we have

\[x^{\ast} - x_{n}<\varepsilon\text{ for all }n\geq n_{0}.\]

Since \(x^{\ast}\) is an upper bound for the set \(\{x_{n} : n\in\N\},\) we know that \(x^{\ast}\geq x_{n}\) for all \(n\in\N\). Therefore

\[|x^{\ast} - x_{n}|<\varepsilon\text{ for all }n\geq n_{0}.\]

Therefore, for an arbitrary \(\varepsilon>0\) we have found a natural number \(n_{0}\) such that

\[|x^{\ast} - x_{n}|<\varepsilon\text{ for all }n\geq n_{0},\]

that is, \(\lim(x_{n}) = x^{\ast}.\)

Proof continued. We wish to show that \(\lim(x_{n}) = x^{\ast}.\) Let \(\varepsilon>0\) be given. By the definition of the least upper bound, the number \(x^{\ast}-\varepsilon\) is not an upper bound for \(\{x_{n} : n\in\N\}\). That is, there is some \(n_{0}\in\N\) such that \(x_{n_{0}}>x^{\ast} - \varepsilon\). Because of our assumption that \((x_{n})\) is increasing, if \(n\geq n_{0}\) then \(x_{n}\geq x_{n_{0}}>x^{\ast} - \varepsilon.\) Rearranging, we have

\[x^{\ast} - x_{n}<\varepsilon\text{ for all }n\geq n_{0}.\]

Since \(x^{\ast}\) is an upper bound for the set \(\{x_{n} : n\in\N\},\) we know that \(x^{\ast}\geq x_{n}\) for all \(n\in\N\). Therefore

\[|x^{\ast} - x_{n}|<\varepsilon\text{ for all }n\geq n_{0}.\]

Therefore, for an arbitrary \(\varepsilon>0\) we have found a natural number \(n_{0}\) such that

\[|x^{\ast} - x_{n}|<\varepsilon\text{ for all }n\geq n_{0},\]

that is, \(\lim(x_{n}) = x^{\ast}.\)

Case 2. Suppose \((x_{n})\) is decreasing.

Pause the video and write out the proof of Case 2.

Example 1. Define the sequence \((y_{n})\) as follows:

\[y_{1} = 8\quad\text{and}\quad y_{n} = \frac{1}{2}y_{n-1}+2 \text{ for all }n\geq2.\]

Let's look at the first few terms:

\[(y_{n}) = \left(8, 6, 5, \frac{9}{2},\frac{17}{4},\frac{33}{8},\ldots\right).\]

Note that \(y_{1}\geq y_{2}\). If we assume that \(y_{k-1}\geq y_{k}\), then we have

\[y_{k+1} = \frac{1}{2}y_{k}+2\leq \frac{1}{2}y_{k-1}+2 = y_{k}\]

hence, \(y_{k}\geq y_{k+1}\). Thus, by induction we see that \((y_{k})\) is decreasing.

Finally, we see that \(y_{1} = 8\geq 0\). If we assume \(y_{k}\geq 0\) for some \(k\in\N\), then we see that \(y_{k+1} = \frac{1}{2}y_{k}+2\geq 0+2\geq 0\). Hence, by induction, we see that \(y_{n}\geq 0\) for all \(n\in\N\). That is, \((y_{n})\) is bounded.

By the Monotone convergence theorem the sequence \((y_{n})\) is convergent.

Practice problem. Define the sequence \(Z = (z_{n})\) as follows

\[z_{1} = 5\quad\text{and}\quad z_{n} = \frac{1}{3}z_{n-1}+1\quad\text{for }n\geq 2.\]

Use induction to prove that \(Z\) is decreasing and and \(z_{n}\geq 1\) for all \(n\in\N\). Use the monotone convergence theorem to show prove that \(Z\) is convergent.

We will start out by writing out the first few terms

\[Z = \left(5,\frac{8}{3},\frac{17}{9},\frac{44}{27},\ldots\right).\]

From this it appears that \(Z\) is decreasing. We can see that \(z_{1} = 5\geq \frac{8}{3} = z_{2}\). Now, we assume \(z_{k-1}\geq z_{k}\) for some \(k\geq 2\), then we see that

\[z_{k} = \frac{1}{3}z_{k-1} + 1\geq \frac{1}{3}z_{k} + 1 = z_{k+1}.\]

This prove the inductive step, and we conclude that

\[z_{n}\geq z_{n+1}\quad\text{for all }n\in\N.\]

Thus, we have established that \(Z\) is decreasing.

Next we note that \(z_{1} = 8\geq 1\). Now, assume that \(z_{k}\geq 1\) for some \(k\in\N\). Note that

\[z_{k+1} = \frac{1}{3}z_{k} +1\geq \frac{1}{3}(1)+1\geq 1.\]

This establishes the inductive step, and shows that \(z_{n}\geq 1\) for all \(n\in \N\).

Finally, since \(Z\) is decreasing, we see that \(z_{n}\leq z_{1}=5\) for all \(n\in\N\). Thus, we have \(1\leq z_{n}\leq 5\) for all \(n\in\N\). In particular, this implies \(|z_{n}|\leq 5\) for all \(n\in\N\), that is, \(Z\) is bounded. Since \(Z\) is bounded and monotonic, by the Monotone Convergence Theorem \(Z\) is convergent.

Case 2: Suppose \((x_{n})\) is decreasing. Since \((x_{n})\) is bounded, there is a number \(M\) such that

\[|x_{n}|\leq M\text{ for all }n\in\N.\]

This implies

\[x_{n}\geq -M\text{ for all }n\in\N.\]

Thus, \(-M\) is an lower bound for the set \(\{x_{n} : n\in\N\}\). By the completeness property of \(\R\) this set has an infimum, call it \(y^{\ast}\).

We wish to show that \(\lim(x_{n}) = y^{\ast}.\) Let \(\varepsilon>0\) be given. By the definition of the infimum, the number \(y^{\ast}+\varepsilon\) is not a lower bound for \(\{x_{n} : n\in\N\}\). That is, there is some \(n_{0}\in\N\) such that \(x_{n_{0}}<y^{\ast} + \varepsilon\). Because of our assumption that \((x_{n})\) is decreasing, if \(n\geq n_{0}\) then \(x_{n}\leq x_{n_{0}}<y^{\ast} + \varepsilon.\) Rearranging, we have

\[x_{n} - y^{\ast}<\varepsilon\text{ for all }n\geq n_{0}.\]

Since \(y^{\ast}\) is a lower bound for the set \(\{x_{n} : n\in\N\},\) we know that \(y^{\ast}\leq x_{n}\) for all \(n\in\N\). Therefore

\[|y^{\ast} - x_{n}| = x_{n} - y^{\ast}<\varepsilon\text{ for all }n\geq n_{0}.\]

Therefore, for an arbitrary \(\varepsilon>0\) we have found a natural number \(n_{0}\) such that

\[|y^{\ast} - x_{n}|<\varepsilon\text{ for all }n\geq n_{0},\]

that is, \(\lim(x_{n}) = y^{\ast}.\)