Lecture 25:

Bolzano-Weierstrass

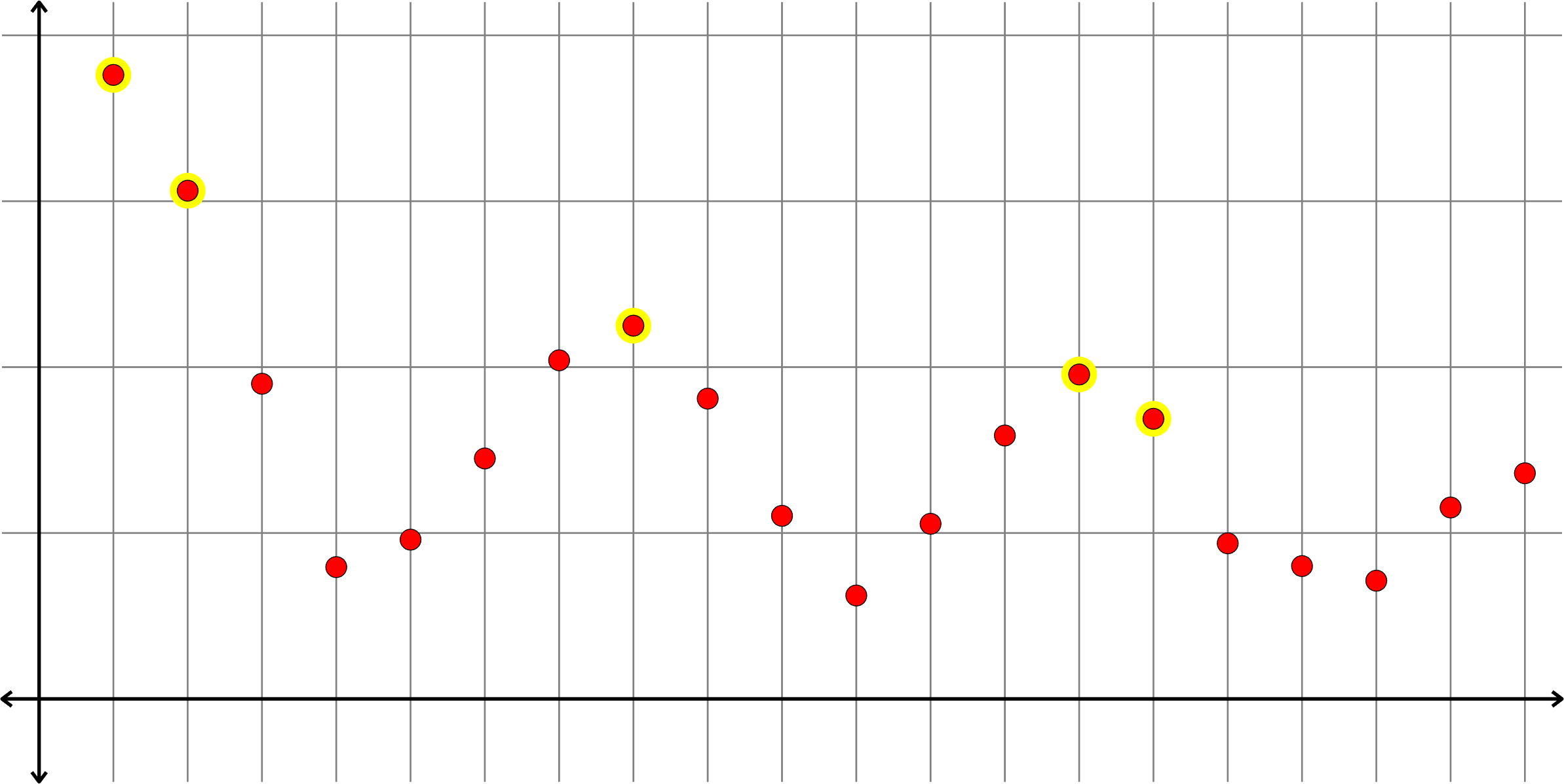

Definition. Give a sequence \(X = (x_{n})\), we say that the \(m\)th term \(x_{m}\) is a peak of the sequence \(X\) if

\[x_{m}\geq x_{n}\text{ for all }n\geq m.\]

A sequence with three peaks highlighted:

Theorem (Monotone Subsequence Theorem). If \(X=(x_{n})\) is a sequence of real numbers, then there is a subsequence of \(X\) that is monotone.

Proof. We will consider two cases. The first where \(X\) has infinitely many peaks, and the second where \(X\) has finitely (possibly zero) peaks.

Case 1. Suppose \(X\) has infinitely many peaks. Let \(n_{k}\) be the index of the \(k\)th peak, and hence \(n_{1}<n_{2}<\cdots < n_{k}<\cdots\). By the definition of a peak we have

\[x_{n_{k}}\geq x_{n_{k+1}}\text{ for all }k\in\N.\]

Therefore, the subsequence \((x_{n_{k}})\) is decreasing.

Case 2. Suppose \(X\) has finitely many peaks. Let \(n_{0}\in\N\) be the largest number such that \(x_{n_{0}}\) is a peak, and set \(n_{0}=0\) if \(X\) has no peaks. Set \(n_{1} = n_{0}+1\).

Since \(x_{n_{1}}\) is not a peak, we can find a number \(n_{2}>n_{1}\) such that \(x_{n_{2}}>x_{n_{1}}\).

Since \(x_{n_{2}}\) is not a peak, there is a natural number \(n_{3}>n_{2}\) such that \(x_{n_{3}}>x_{n_{2}}\).

Since \(x_{n_{3}}\) is not a peak...

We can carry on in this manner to obtain a sequence of natural numbers \(n_{1}<n_{2}<\cdots<n_{k}<\cdots\) such that

\[x_{n_{1}}<x_{n_{2}}<\cdots<x_{n_{k}}<\cdots.\]

Therefore the subsequence \((x_{n_{k}})\) is increasing. \(\Box\)

Theorem (Bolzano-Weierstrass). Every bounded sequence has a convergent subsequence.

Proof. Suppose \(X = (x_{n})\) is a bounded sequence. By the Monotone Subsequence Theorem there is a monotone subsequence \(X' = (x_{n_{k}}).\) A subsequence of a bounded sequence is clearly bounded, hence \(X'\) is bounded. By the Monotone Convergence Theorem the sequence \(X'\) converges. \(\Box\)

Theorem. Suppose \(X=(x_{n})\) is a sequence. If \(\lim X\neq x\) then there is an \(\varepsilon_{0}>0\) and a subsequence \(X'=(x_{n_{k}})\) such that

\[|x_{n_{k}}-x|\geq\varepsilon_{0}\text{ for all }k\in\N.\]

Proof. Since \(\lim(X)\neq x\), there is some \(\varepsilon_{0}>0\) such that for any \(K\in\N\) there exists a natural number \(n\geq K\) such that \(|x_{n}-x|\geq \varepsilon_{0}.\)

In particular, since \(1\in\N\), there is a natural number \(n_{1}\geq 1\) such that \(|x_{n_{1}}-x|\geq \varepsilon_{0}\).

Since \(n_{1}+1\in\N\), there is a natural number \(n_{2}\geq n_{1}+1>n_{1}\) such that \(|x_{n_{2}}-x|\geq \varepsilon_{0}\). We've defined \(n_{1}\) and \(n_{2}\).

Since \(n_{2}+1\in\N\), there is a natural number \(n_{3}\geq n_{2}+1>n_{2}\) such that \(|x_{n_{3}}-x|\geq \varepsilon_{0}\).

Continuing we end up with a sequence of natural numbers

\(n_{1}<n_{2}<n_{3}<\cdots<n_{k}<\cdots\) such that \(|x_{n_{k}}-x|\geq \varepsilon_{0}\) for each \(k\in\N\). \(\Box\)

Theorem. Suppose \(X=(x_{n})\) is a sequence. If \(X\) is bounded and divergent, then there exist two convergent subsequences \(X'=(x_{n_{k}})\) and \(X''=(x_{m_{k}})\) such that

\[\lim X' \neq \lim X''.\]

Proof. By the Bolzono-Weierstrass theorem, the sequence \(X\) has a convergent subsequence, call it \(X'\). Suppose \(\lim X'=a\). Since \(X\) is divergent we know that \(\lim X\neq a\). By the previous theorem there is a subsequence \(Z=(x_{r_{k}})\) and a positive number \(\varepsilon_{0}\) such that

\(|x_{r_{k}}-a|\geq\varepsilon_{0}\) for all \(k\in\N\). Again, by the Bolzono-Weierstrass theorem there exists a convergent subsequence \(X''\) of \(Z\). Since \(Z\) is a subsequence of \(X\), and \(X''\) is a subsequence \(Z\), we see that \(X''\) is a subsequence of \(X\). Thus we have \(X'' = (x_{m_{k}})\) for some numbers \(m_{1}<m_{2}<\cdots<m_{k}<\cdots\). We also have \(|x_{m_{k}}-a|\geq \varepsilon_{0}\) for all \(k\in\N\), and hence \(\lim X''\neq a = \lim X'\). \(\Box\)

Theorem (The Divergence Criteria). A sequence \(X=(x_{n})\) is divergent if and only if one of the following two statements holds:

- \(X\) is unbounded

- There exist two convergent subsequences \(X'\) and \(X''\) of \(X\) such that \(\lim X'\neq \lim X''\).

Proof. First assume \(X\) is divergent. If \(X\) is unbounded then we are done. If \(X\) is bounded, then the previous theorem shows that statement 2 above holds.

Now, assume statement 1 above holds. Since convergent sequences are bounded, this implies that undbounded sequences are divergent.

Finally, suppose statement 2 above holds. By the Divergence Criteria (i) from Lecture 24 we see that \(X\) is divergent. \(\Box\)

Practice Problem. Show that the sequence \((2^{n})\) diverges by showing that it is unbounded. (Hint: use induction to prove that \(2^n\geq n\) for all \(n\in\N\).)

Proof. First we will use induction to show that \(2^{n}\geq n\) for all \(n\in\N\). For the base case of \(n=1\) we simply note that \(2^1=2\geq1\). Now, we assume \(2^{k}\geq k\) for some \(k\in\N\). Note that since \(k\geq 1\), if we add \(k\) to both sides we obtain \(2k\geq k+1\), and thus \(2k\geq k+1\). Using the inductive assumption we see that \(2^{k+1}\geq 2k\). Putting these last two inequalities together we have \(2^{k+1}\geq k+1\). This completes the inductive step.

Now, let \(M>0\) be arbitrary. Let \(m\in\N\) such that \(m>M\). By the first part of the proof \(2^{m}\geq m>M\). Thus it is not true that \(|2^{n}|\leq M\) for all \(n\in\N\). That is, \(M\) is not a bound for the sequence \((2^{n})\). Since \(M\) was an arbitrary positive number, this shows that no positive number is a bound for \((2^{n})\), that is, \((2^{n})\) is unbounded. By the Divergence Criteria \((2^{n})\) is divergent. \(\Box\)