Lecture 33:

The Intermediate Value Theorem

The Bump Theorem. If \(f:A\to\R\) is continuous at \(c\in A\) and \(f(c)>0\), then there exists \(\delta>0\) so that \(f(x)>0\) for all \(x\in A\cap V_{\delta}(c)\).

Proof. Since \(f\) is continuous at \(c\) and \(f(c)>0\), there is a \(\delta>0\) so that \[|f(x)-f(c)|<\frac{f(c)}{2}\quad\text{for all }x\in A\cap V_{\delta}(c)\]

Hence, if \(x\in A\cap V_{\delta}(c)\) then

\[-\frac{f(c)}{2}<f(x)-f(c)<\frac{f(c)}{2}\]

and hence

\[0<\frac{f(c)}{2}<f(x).\]

\(\Box\)

The Bump Theorem (Negative Version). If \(f:A\to\R\) is continuous at \(c\in A\) and \(f(c)<0\), then there exists \(\delta>0\) so that \(f(x)<0\) for all \(x\in A\cap V_{\delta}(c)\).

Proof. Since \(f\) is continuous at \(c\) and \(f(c)>0\), there is a \(\delta>0\) so that \[|f(x)-f(c)|<-\frac{f(c)}{2}\quad\text{for all }x\in A\cap V_{\delta}(c)\]

Hence, if \(x\in A\cap V_{\delta}(c)\) then

\[\frac{f(c)}{2}<f(x)-f(c)<-\frac{f(c)}{2}\]

and hence

\[f(x)<\frac{f(c)}{2}<0.\]

\(\Box\)

Definition 5.1.5. Let \(A\subset\R\) and let \(f:A\to\R\). If \(B\subseteq A\), we say that \(f\) is continuous on the set \(B\) if \(f\) is continuous at every point of \(B\).

Example. The function \(f(x)=x^2\) is continuous on \(\R\).

Proof. Let \(c\in\R\) be arbitrary. Let \(\varepsilon>0\) be arbitrary. Set \[\delta = \min\left\{1,\frac{\varepsilon}{2(1+|2c|)}\right\}.\] Let \(x\in\R\) such that \(|x-c|<\delta\). From the triangle inequality we have \[|x+c| = |x-c+2c|\leq |x-c|+|2c|<\delta+|2c|=1+|2c|.\]

Using this we have

\[|f(x)-f(c)| = |x^2-c^2|=|x-c||x+c|\leq \frac{\varepsilon}{2(1+|2c|)}\cdot(1+|2c|)\]

\[=\frac{\varepsilon}{2}<\varepsilon.\]

\[\Box\]

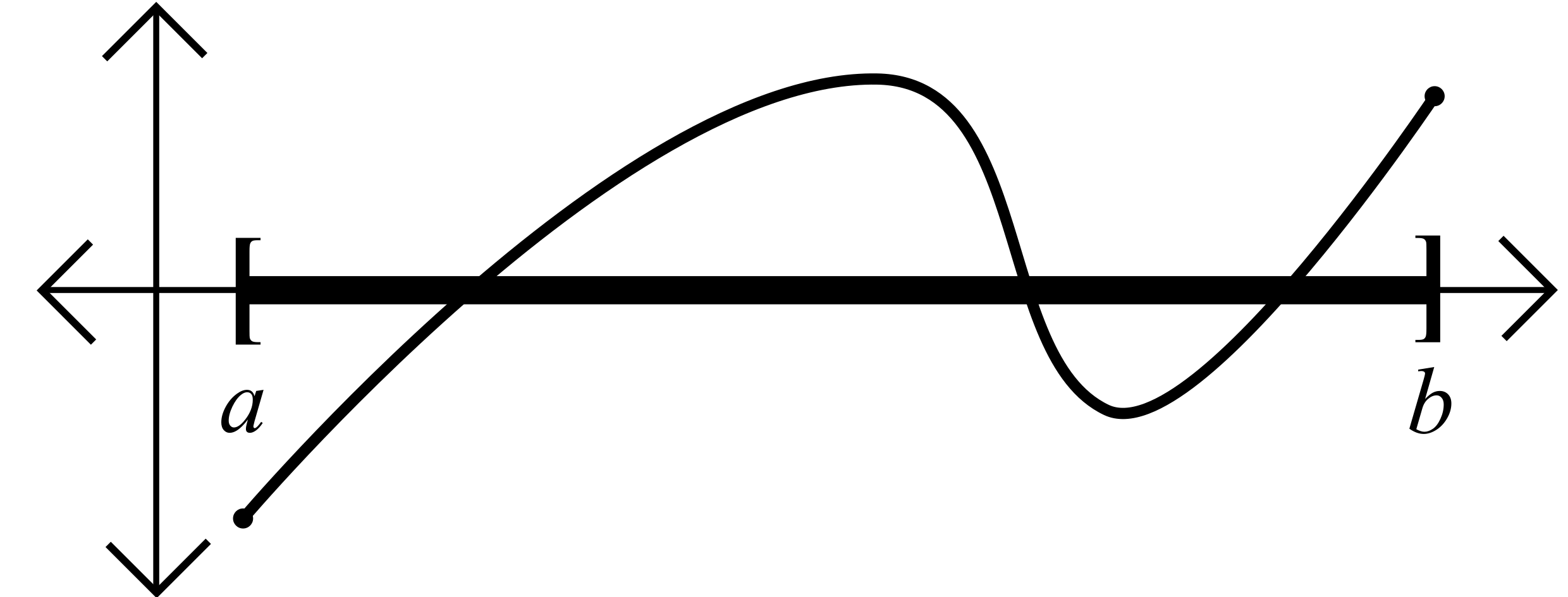

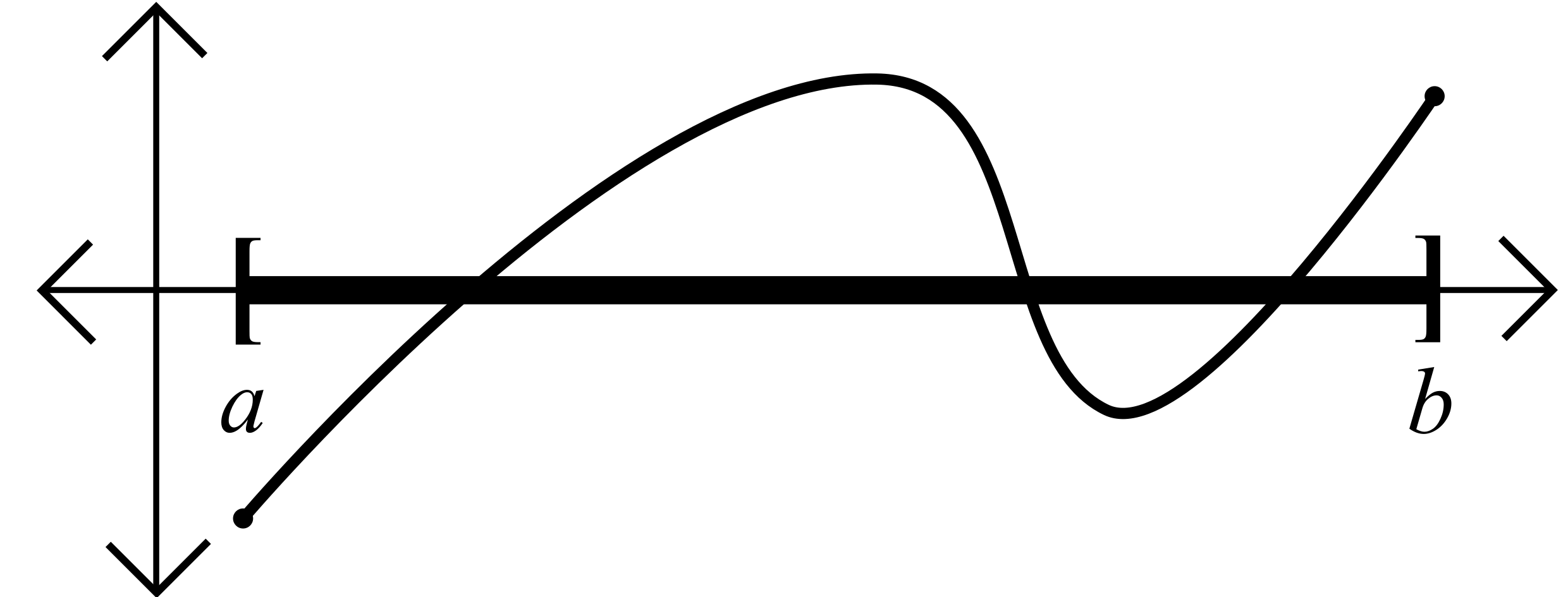

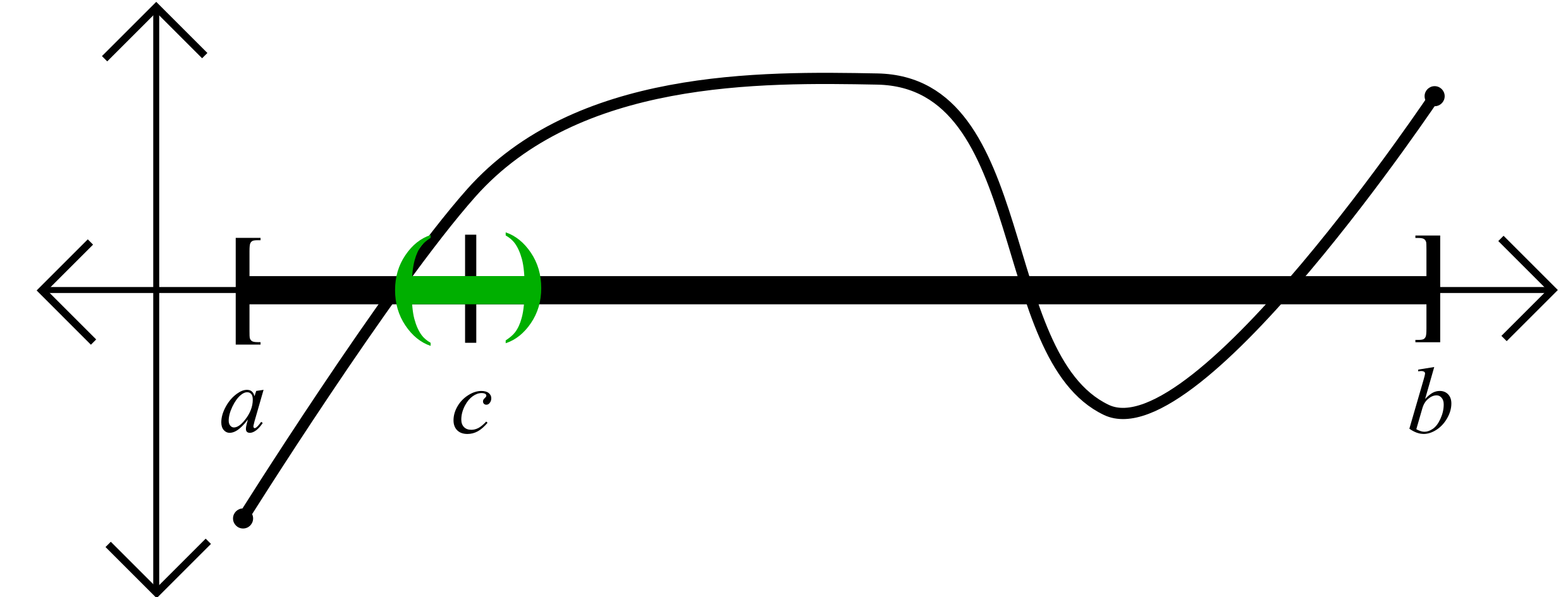

Theorem 5.3.5 (Location of Roots Theorem). Let \(I=[a,b]\) and let \(f:I\to\R\) be continuous on \(I\). If \(f(a)<0<f(b)\), then there exists a number \(c\in(a,b)\) such that \(f(c) = 0\).

Idea of the Proof.

- Define the set \(A = \{x\in[a,b] : f(y)<0\text{ for all }y\text{ such that }a\leq y\leq x\}.\)

- Set \(c=\sup A.\)

- Show that \(c>a\)

- Show that \(f(x)<0\) for all \(x\in[a,c)\)

- Show that assuming \(f(c)>0\) leads to a contradiction.

- Show that assuming \(f(c)<0\) leads to a contradiction.

Theorem 5.3.5 (Location of Roots Theorem). Let \(I=[a,b]\) and let \(f:I\to\R\) be continuous on \(I\). If \(f(a)<0<f(b)\), then there exists a number \(c\in(a,b)\) such that \(f(c) = 0\).

Idea of the Proof.

- Define the set \(A = \{x\in[a,b] : f(y)<0\text{ for all }y\text{ such that }a\leq y\leq x\}.\)

- \(a\in A\), and hence \(A\neq \varnothing\).

- \(x\in A\) implies \(x\leq b\),

- \(b\) is an upper bound for \(A\)

- \(A\) is bounded above

- \(A\) has a least upper bound.

\(A\)

Theorem 5.3.5 (Location of Roots Theorem). Let \(I=[a,b]\) and let \(f:I\to\R\) be continuous on \(I\). If \(f(a)<0<f(b)\), then there exists a number \(c\in(a,b)\) such that \(f(c) = 0\).

Idea of the Proof.

- Define the set \(A = \{x\in[a,b] : f(y)<0\text{ for all }y\text{ such that }a\leq y\leq x\}.\)

- Set \(c=\sup A.\)

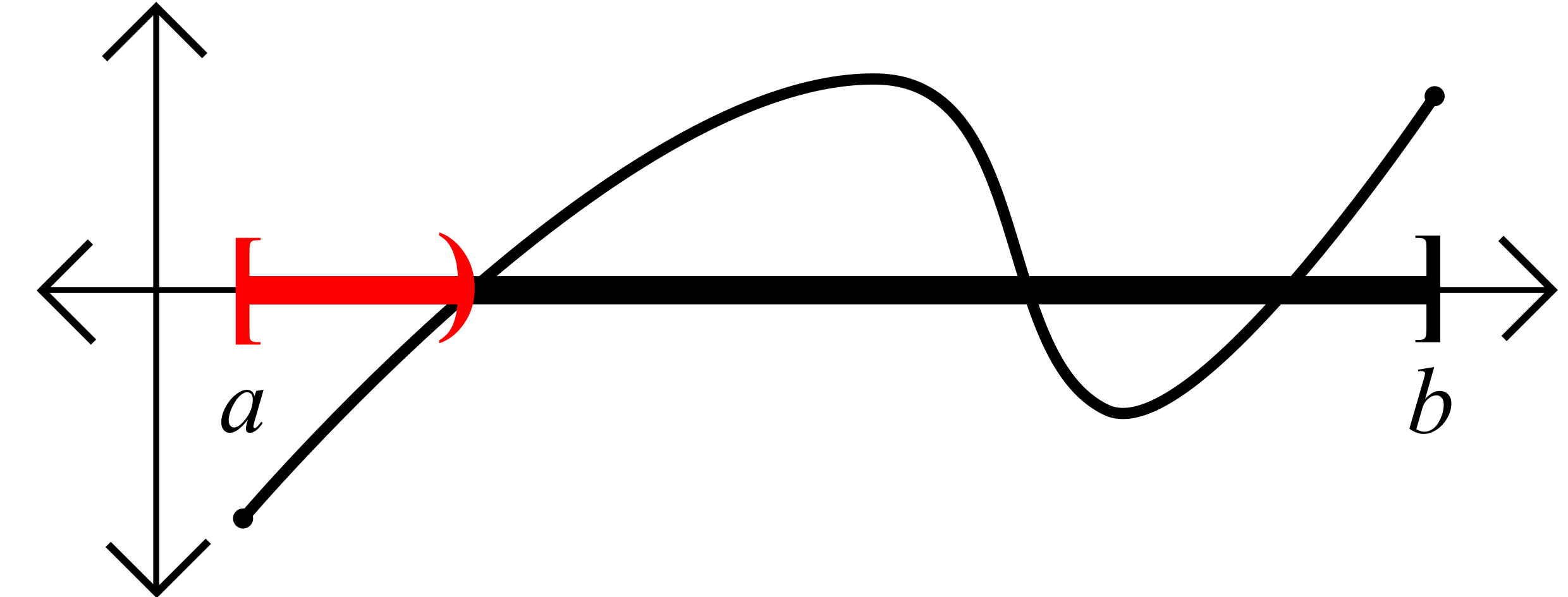

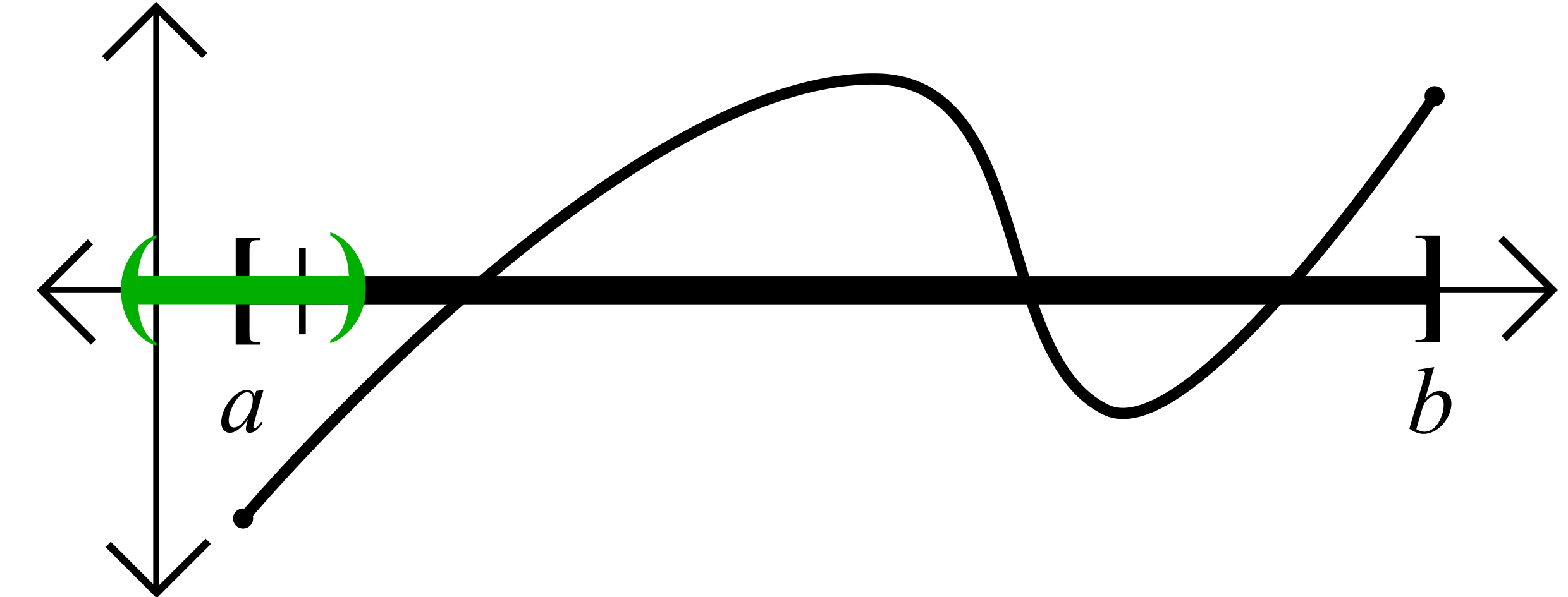

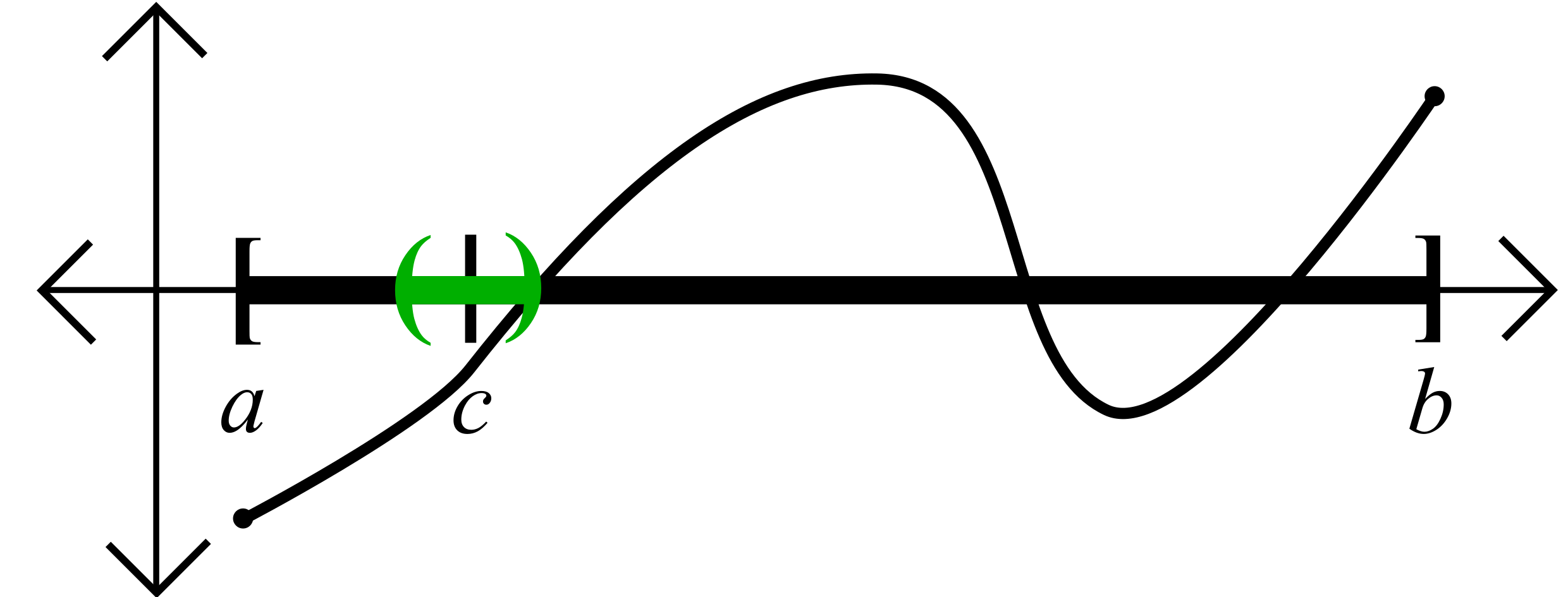

Theorem 5.3.5 (Location of Roots Theorem). Let \(I=[a,b]\) and let \(f:I\to\R\) be continuous on \(I\). If \(f(a)<0<f(b)\), then there exists a number \(c\in(a,b)\) such that \(f(c) = 0\).

Idea of the Proof.

- Define the set \(A = \{x\in[a,b] : f(y)<0\text{ for all }y\text{ such that }a\leq y\leq x\}.\)

- Set \(c=\sup A.\)

- Show that \(c>a\)

- Since \(a\in A\) it follows that \(a\leq c\).

- If \(a=c\), then from the Bump Theorem (Negative Version) \(f(x)<0\) for all \(x\in[a,a+\frac{\delta}{2}].\)

- Thus \(a+\frac{\delta}{2}\in A\)

- But \(a+\frac{\delta}{2}>c\) \(\Rightarrow\Leftarrow\)

\(V_{\delta}(a)\)

\(a+\frac{\delta}{2}\)

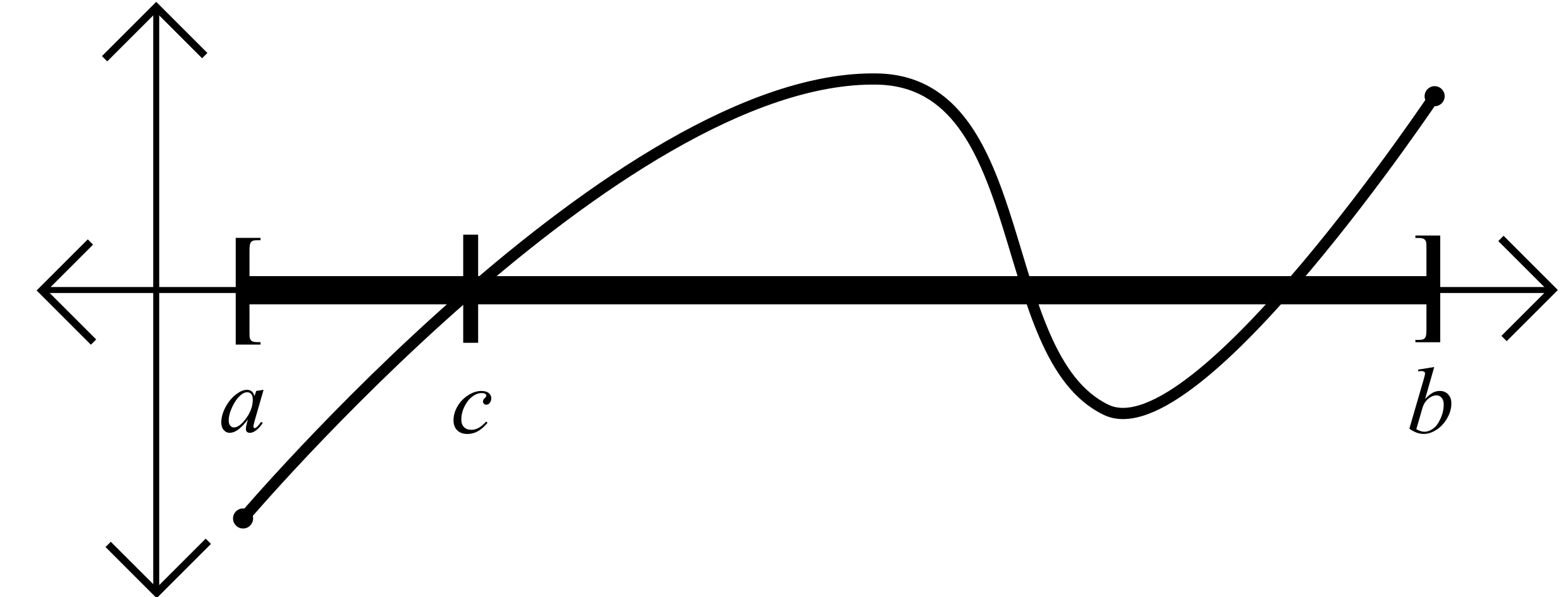

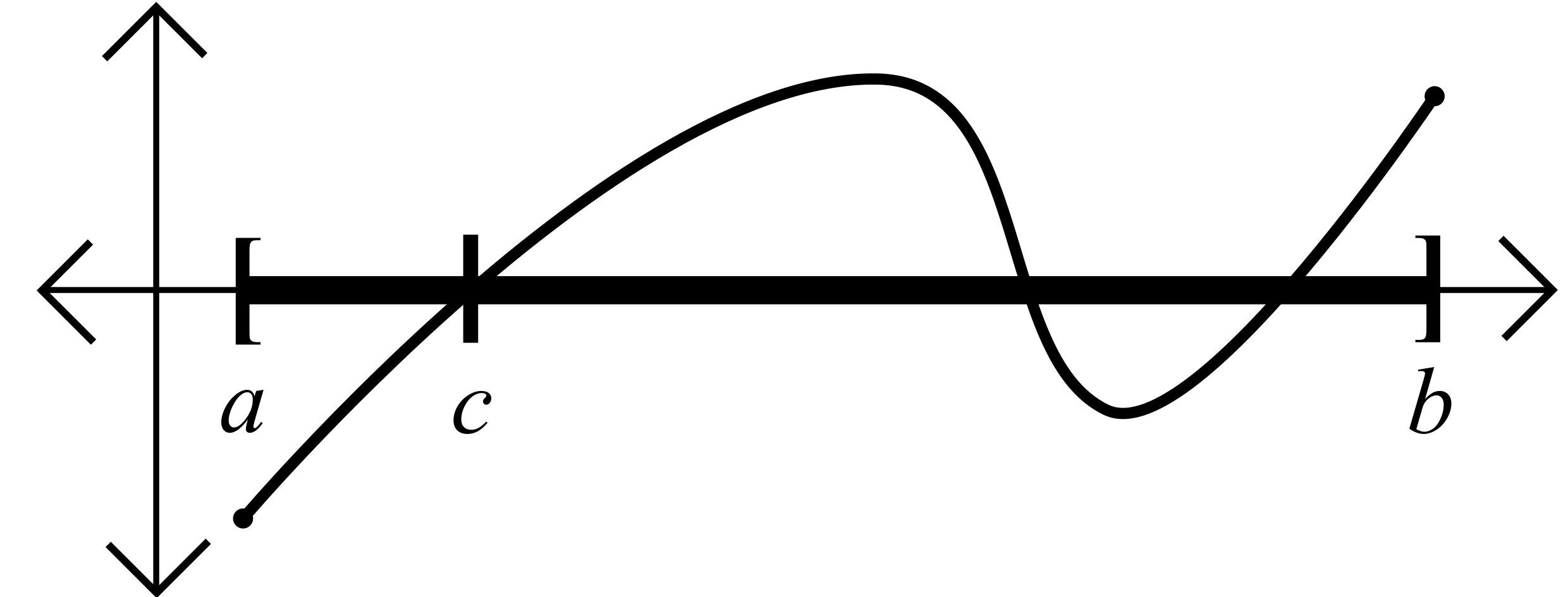

Theorem 5.3.5 (Location of Roots Theorem). Let \(I=[a,b]\) and let \(f:I\to\R\) be continuous on \(I\). If \(f(a)<0<f(b)\), then there exists a number \(c\in(a,b)\) such that \(f(c) = 0\).

Idea of the Proof.

- Define the set \(A = \{x\in[a,b] : f(y)<0\text{ for all }y\text{ such that }a\leq y\leq x\}.\)

- Set \(c=\sup A.\)

- Show that \(c>a\)

- Show that \(f(x)<0\) for all \(x\in[a,c)\)

Theorem 5.3.5 (Location of Roots Theorem). Let \(I=[a,b]\) and let \(f:I\to\R\) be continuous on \(I\). If \(f(a)<0<f(b)\), then there exists a number \(c\in(a,b)\) such that \(f(c) = 0\).

Idea of the Proof.

- Define the set \(A = \{x\in[a,b] : f(y)<0\text{ for all }y\text{ such that }a\leq y\leq x\}.\)

- Set \(c=\sup A.\)

- Show that \(c>a\)

- Show that \(f(x)<0\) for all \(x\in[a,c)\)

- Show that assuming \(f(c)>0\) leads to a contradiction.

By the Bump Theorem \(f(x)>0\) for all \(x\in V_{\delta}(c)\)

\(V_{\delta}(a)\)

\(x<c\) such that \(f(x)>0\)

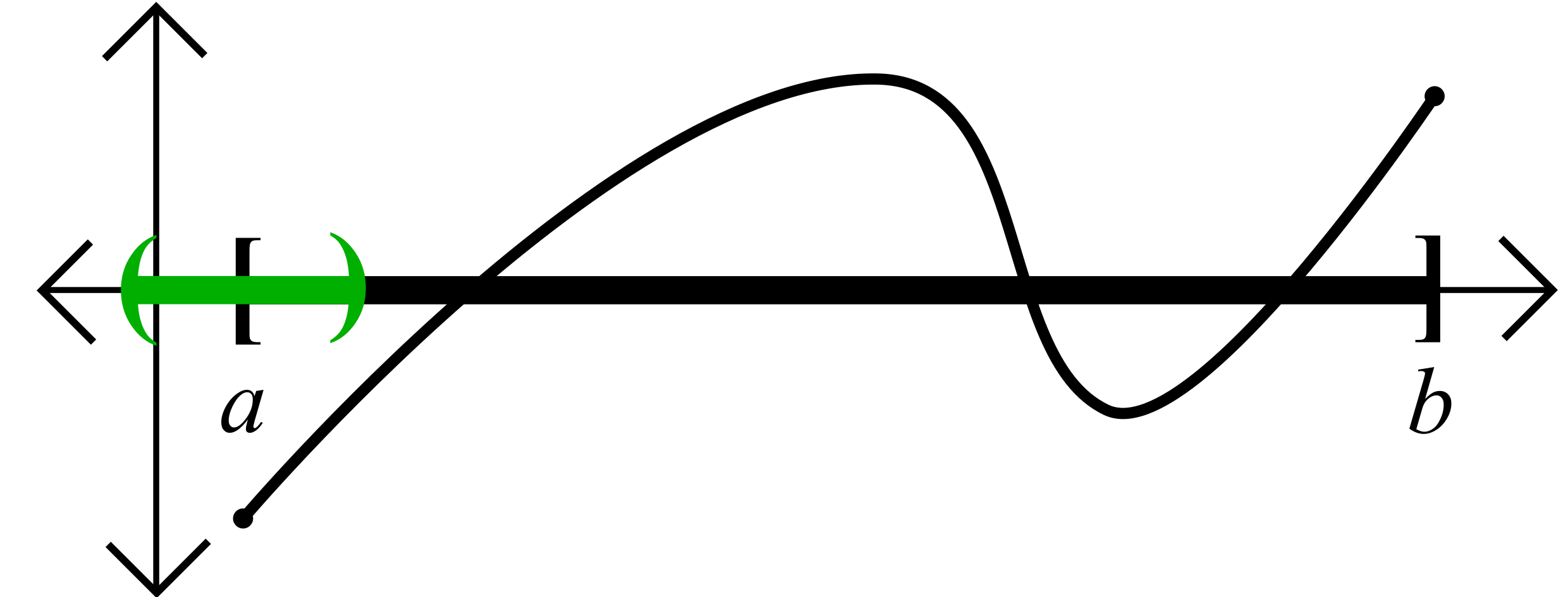

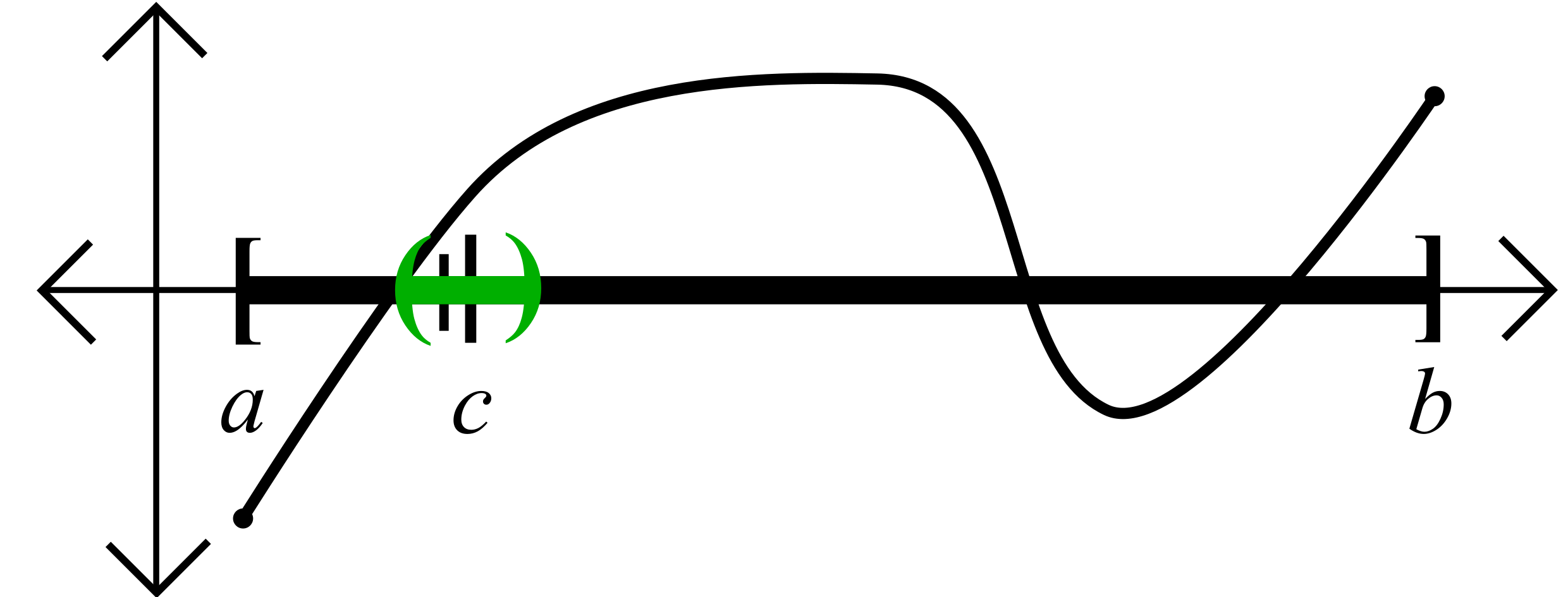

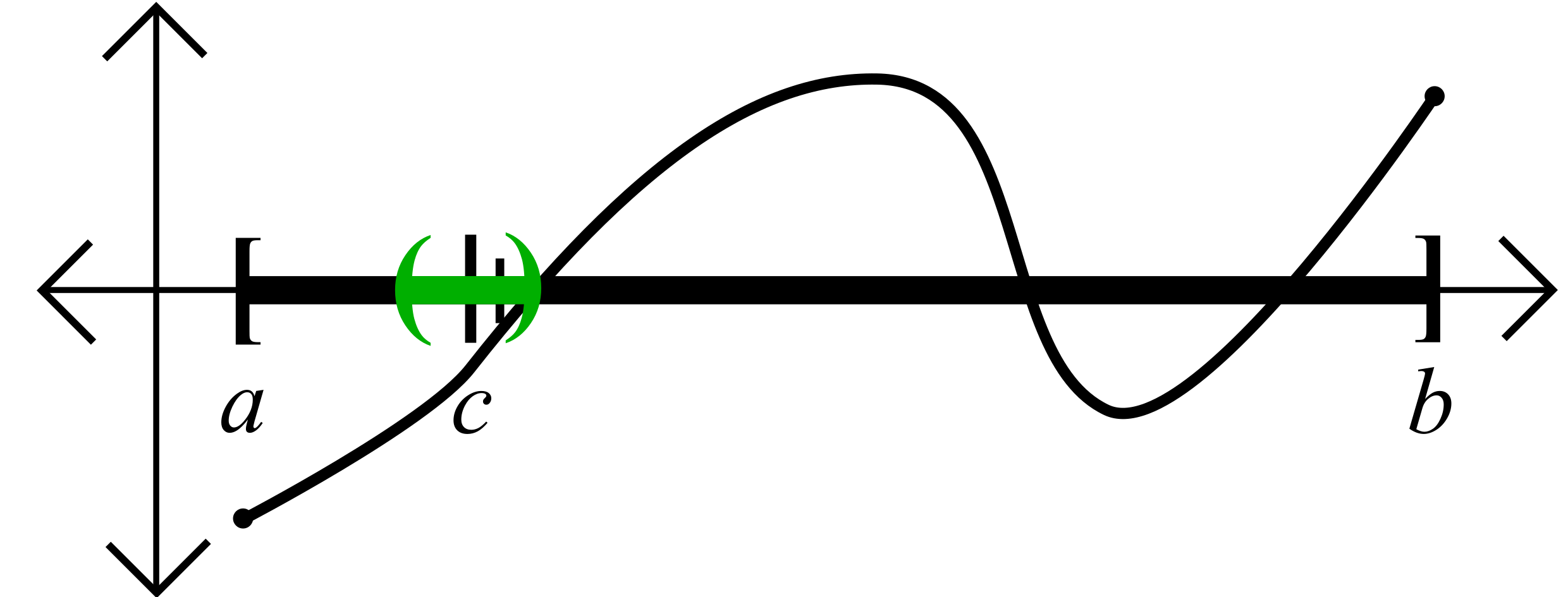

Theorem 5.3.5 (Location of Roots Theorem). Let \(I=[a,b]\) and let \(f:I\to\R\) be continuous on \(I\). If \(f(a)<0<f(b)\), then there exists a number \(c\in(a,b)\) such that \(f(c) = 0\).

Idea of the Proof.

- Define the set \(A = \{x\in[a,b] : f(y)<0\text{ for all }y\text{ such that }a\leq y\leq x\}.\)

- Set \(c=\sup A.\)

- Show that \(c>a\)

- Show that \(f(x)<0\) for all \(x\in[a,c)\)

- Show that assuming \(f(c)>0\) leads to a contradiction.

- Show that assuming \(f(c)<0\) leads to a contradiction.

By the Bump Theorem \(f(x)<0\) for all \(x\in V_{\delta}(c)\)

\(V_{\delta}(a)\)

\(x>c\) such that \(x\in A\)

Theorem 5.3.5 (Location of Roots Theorem). Let \(I=[a,b]\) and let \(f:I\to\R\) be continuous on \(I\). If \(f(a)<0<f(b)\), then there exists a number \(c\in(a,b)\) such that \(f(c) = 0\).

Proof. Define the set

\[A = \{x\in[a,b] : f(y)<0\text{ for all }y\text{ such that }a\leq y\leq x\}.\]

By assumption, \(f(a)<0\) and hence \(a\in A\). By the definition of \(A\) we see that \(b\) is an upper bound for \(A\). Since \(A\) is nonempty and bounded above, by the Completeness Property of \(\R\) we see that \(A\) has a supremum. Set

\[c=\sup A.\]

Since \(a\in A\) we see that \(a\leq c\), and since \(b\) is an upper bound for \(A\) we see that \(c\leq b\). Hence \(c\in[a,b]\).

Proof continued.

Our first claim about \(c\) is that \(c>a.\) By the Bump Theorem, there is a positive number \(\delta>0\) such that

\[f(x)<0\quad\text{ for all }x\in I\cap V_{\delta}(a)\]

In particular, \(f(y)<0\) for all \(y\) such that \(a\leq y\leq a+\frac{\delta}{2}\). This shows that \(a+\frac{\delta}{2}\in A\). Hence \(a<a+\frac{\delta}{2}\leq c\), that is \(c>a\).

Our second claim about \(c\) is the following:

If \(a\leq y<c\) then \(f(y)<0\).

Indeed, if \(a\leq y<c\) then \(y\) is not an upper bound for \(A\). Hence, there is some number \(z\in A\) such that \(z>y\). By the definition of \(A\) we conclude that \(f(y)<0\).

Proof continued.

Now, assume \(f(c)>0\). By the Bump Theorem there is a number \(\delta>0\) such that

\[f(x)>0\quad\text{for all }x\in [a,b]\cap V_{\delta}(c).\]

In particular, there is a number \(x\in[a,b]\) with \(x<c\) such that \(f(x)>0\). This contradicts our second fact from the previous slide. We conclude that \(f(c)\leq 0\).

Finally, assume \(f(c)<0.\) By the Bump Theorem there is a number \(\delta>0\) such that \[f(x)<0\quad\text{for all }x\in[a,b]\cap V_{\delta}(c).\]

Since \(f(c)<0\) we conclude that \(c<b\). Thus, there is some \(d\in(c,b)\) such that \(f(x)<0\) for all \(x\in[c,d].\) We already had \(f(x)<0\) for all \(x\in[a,c)\), and hence \(f(x)<0\) for all \(x\in[a,d]\). This implies \(d\in A,\) and since \(d>c\) this contradicts the fact that \(c\) is an upper bound for \(A\). Hence, it is not the case that \(f(c)<0.\) The only option left is \(f(c)=0.\) \(\Box\)