Lecture 8:

Some Theorems about \(\varepsilon\)-neighborhoods

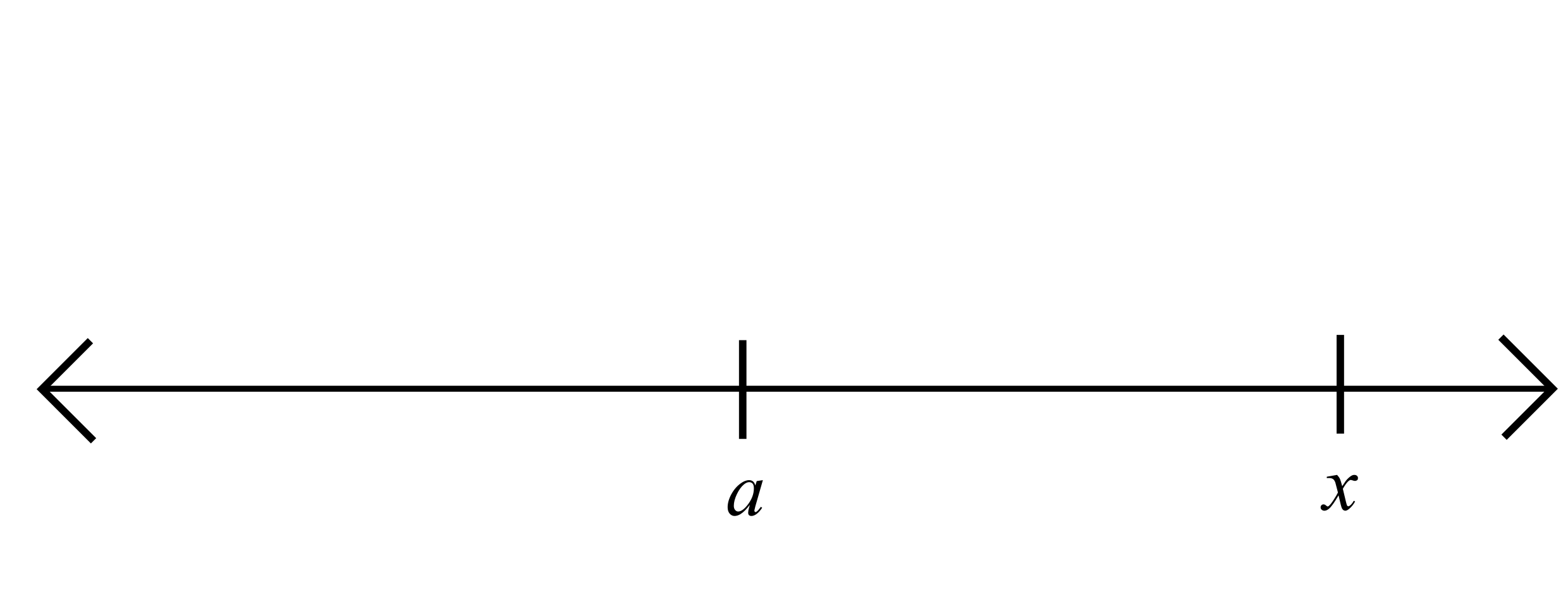

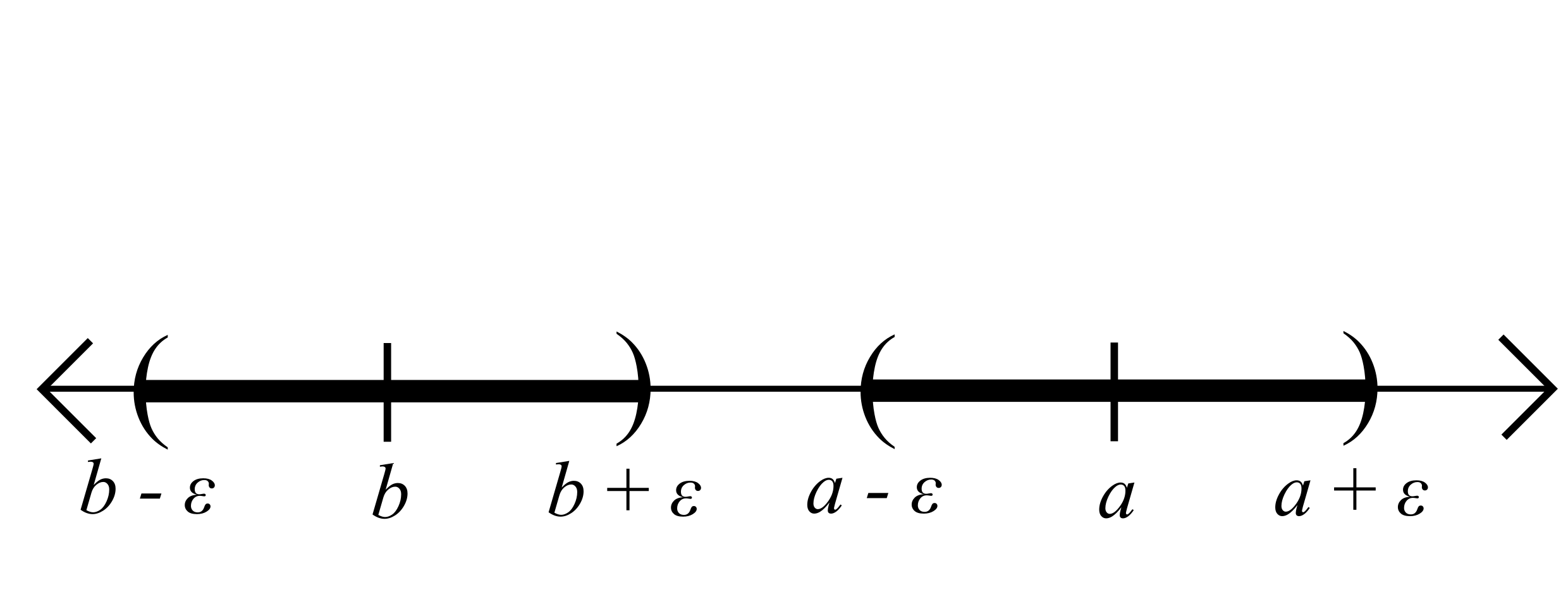

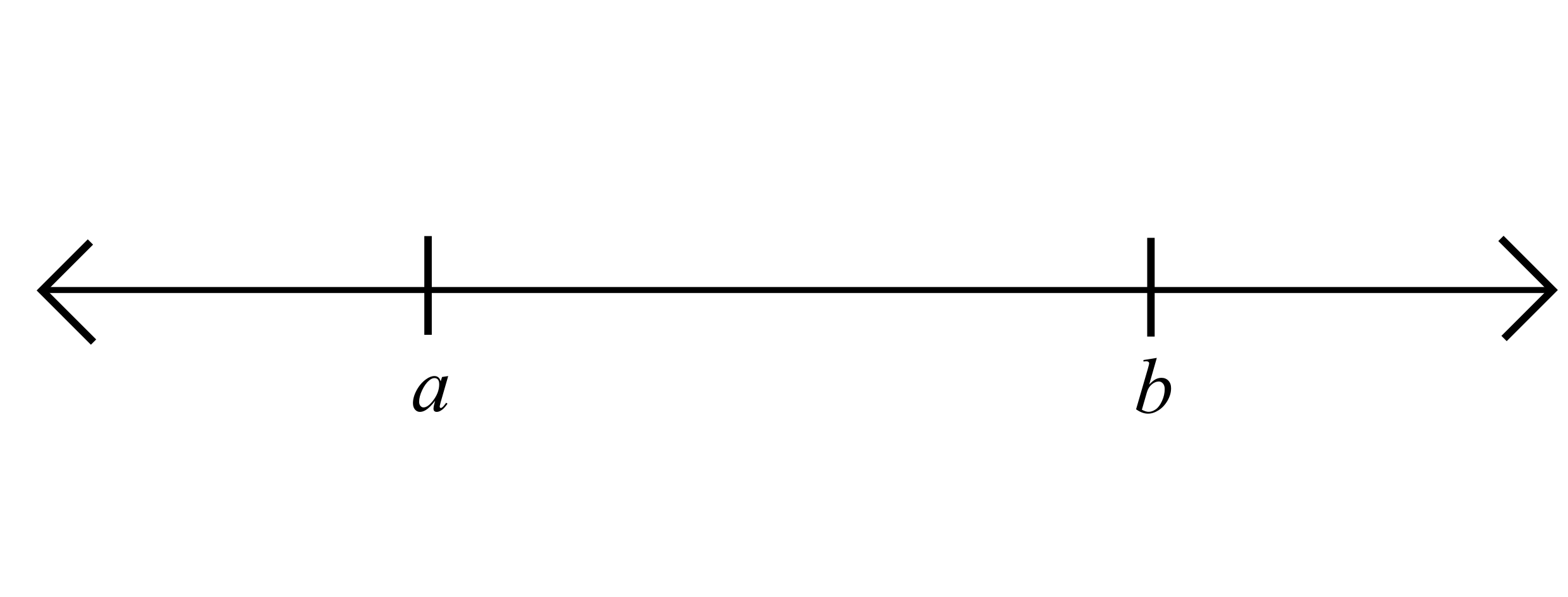

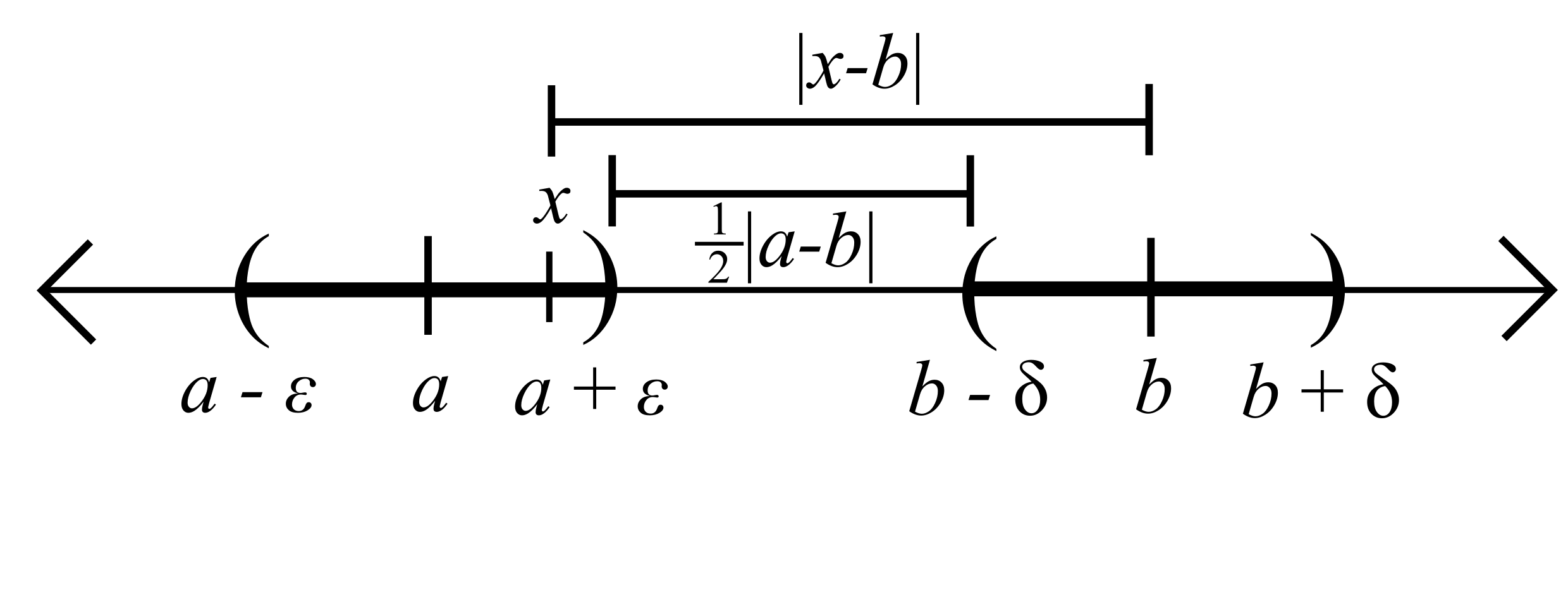

Theorem 2.2.8. Let \(a\) and \(x\) be real numbers. If \(x\in V_{\varepsilon}(a)\) for all \(\varepsilon>0\), then \(x=a\).

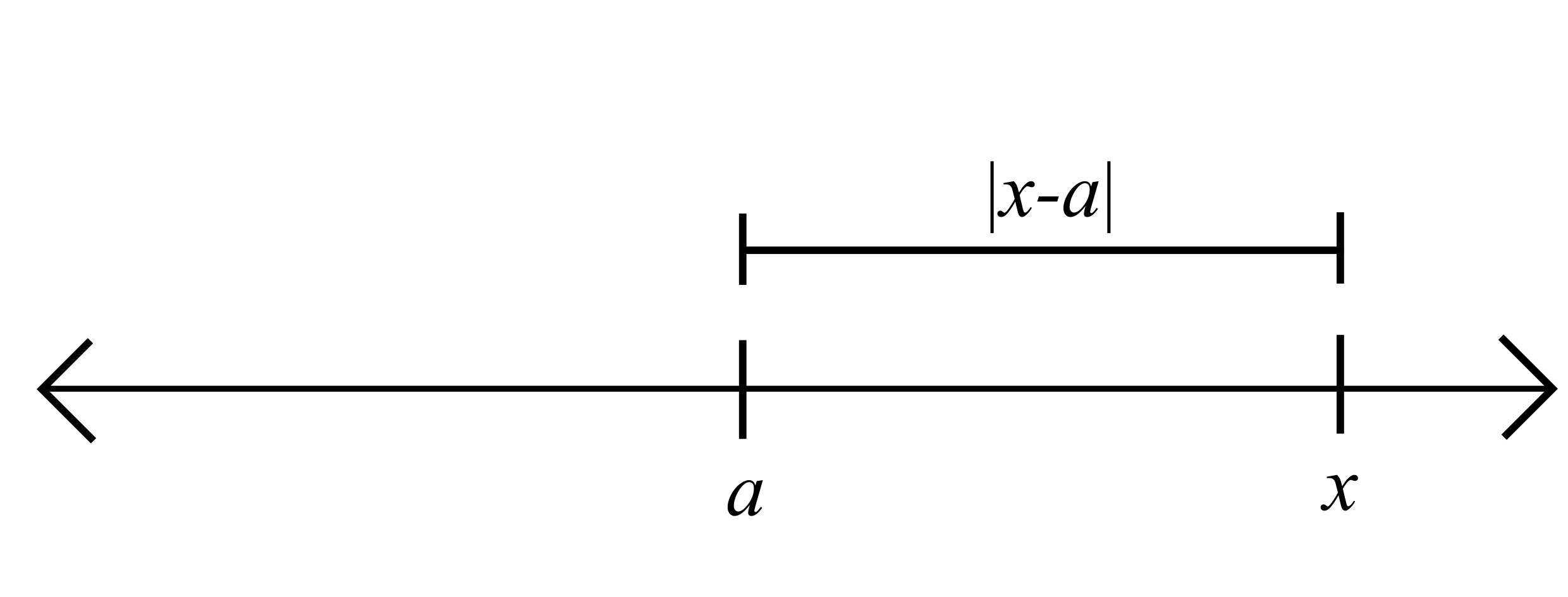

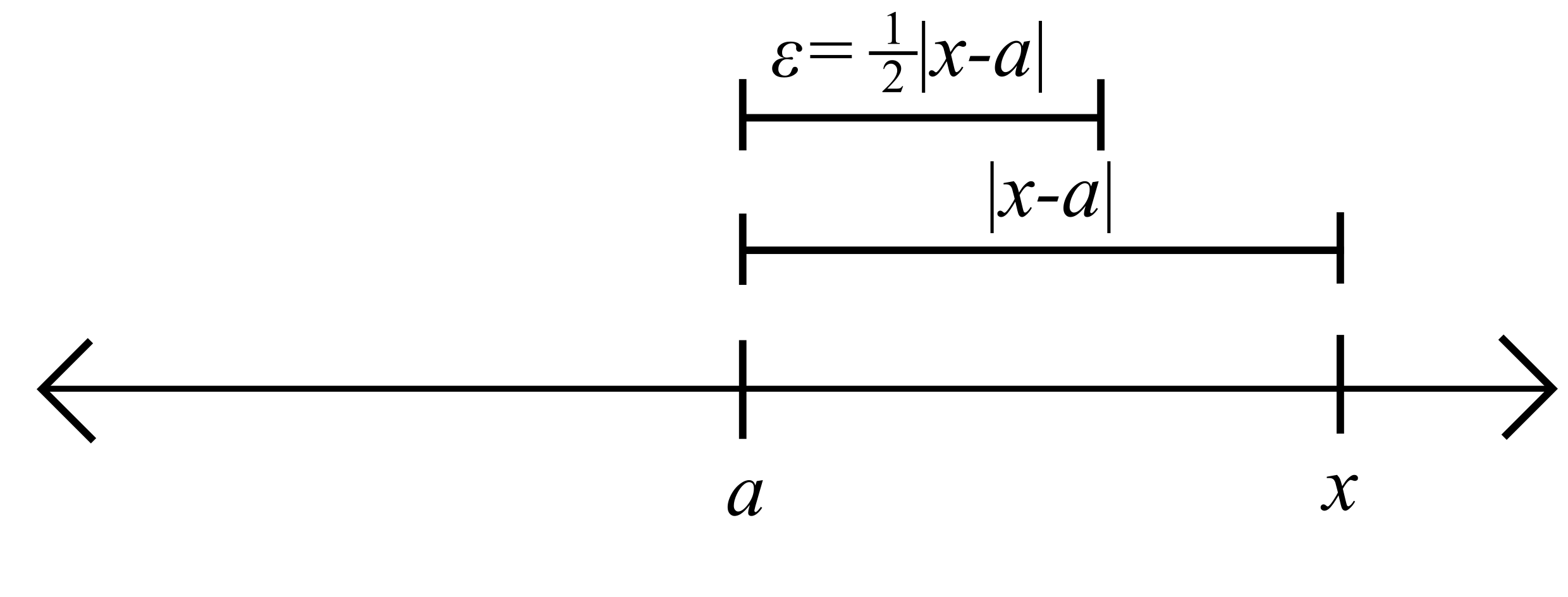

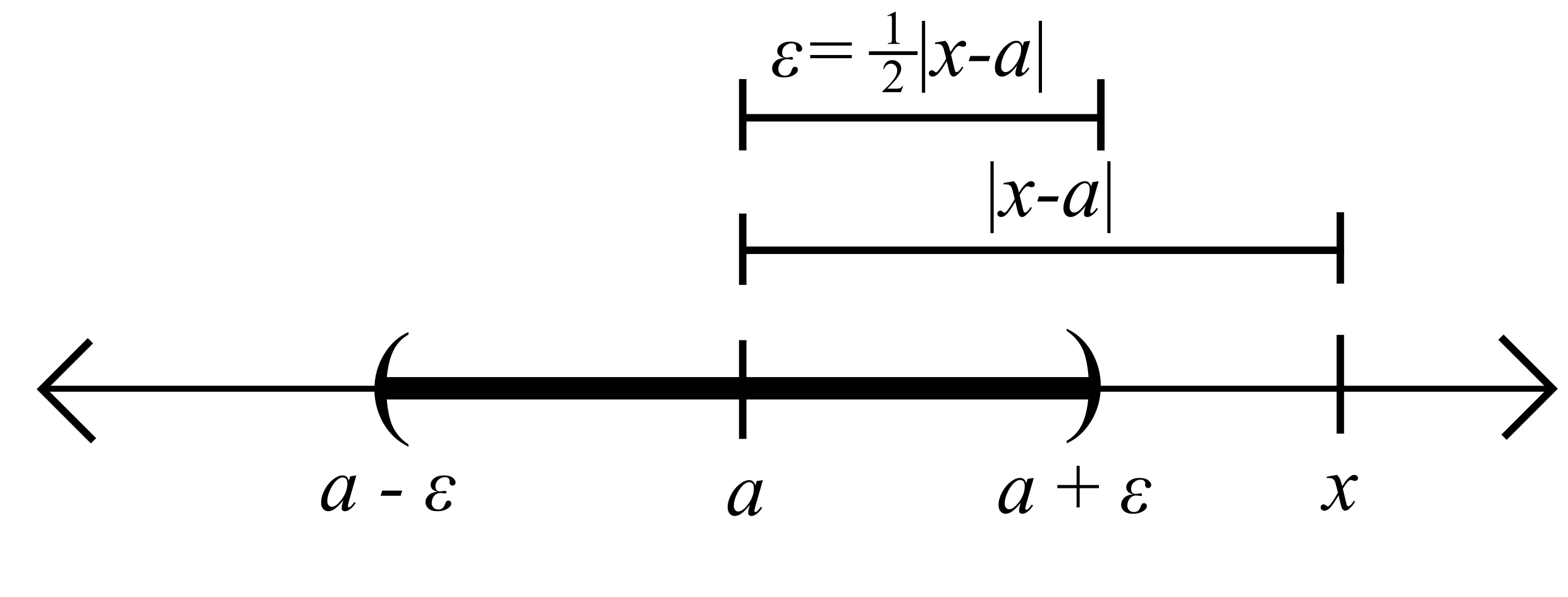

With this choice of \(\varepsilon\), it appears from the picture that \(x\notin V_{\varepsilon}(a)\).

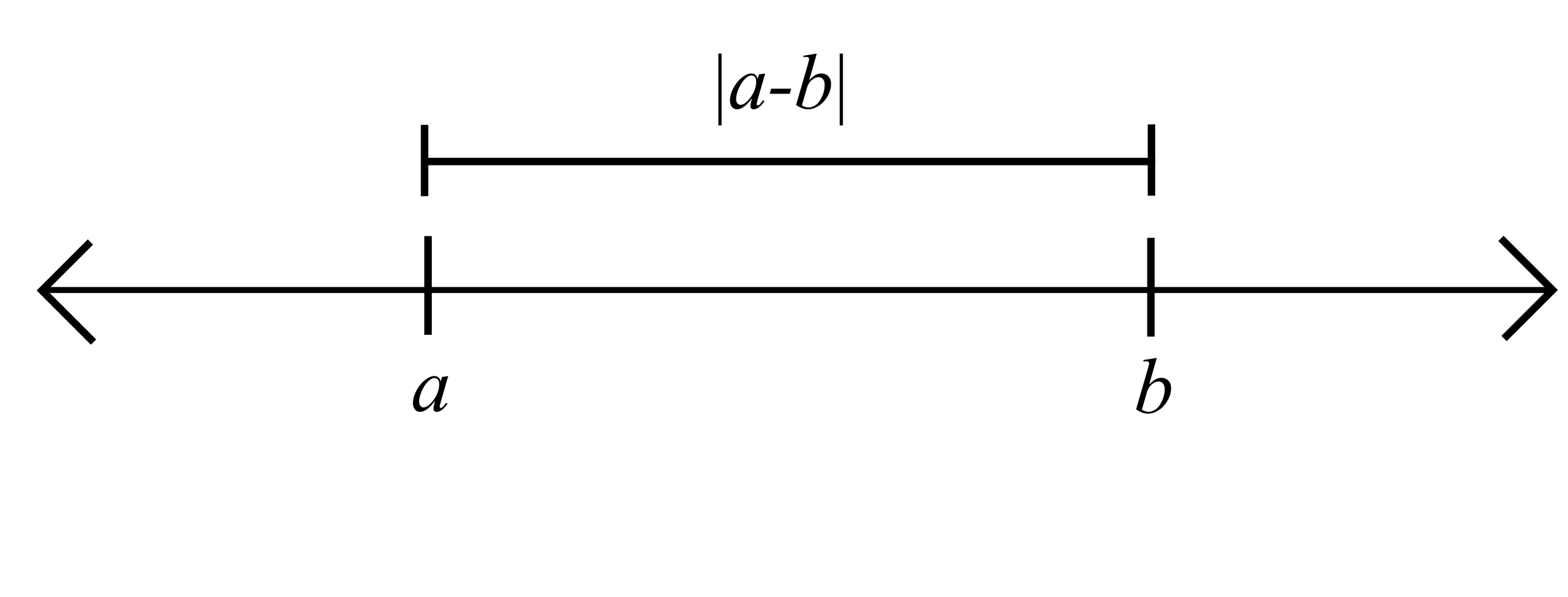

Proof. We will prove this by contrapositive. Assume \(x\neq a\). Set

\[\varepsilon = \frac{1}{2}|x-a|.\]

Since \(x\neq a\), we see that \(\varepsilon>0\). To complete the proof, we note that

\[|x-a|>\frac{1}{2}|x-a| = \varepsilon,\]

and therefore \(x\notin V_{\varepsilon}(a)\). \(\Box\)

Theorem 2.2.8. Let \(a\) and \(x\) be real number. If \(x\in V_{\varepsilon}(a)\) for all \(\varepsilon>0\), then \(x=a\).

Proposition. Let \(a\) and \(b\) be real numbers, and let \(\varepsilon>0\).

If \(V_{\varepsilon}(a)\cap V_{\varepsilon}(b) = \varnothing\), then \(|a-b|\geq 2\varepsilon\).

Proposition. Let \(a\) and \(b\) be real numbers, and let \(\varepsilon>0\).

If \(V_{\varepsilon}(a)\cap V_{\varepsilon}(b) = \varnothing\), then \(|a-b|\geq 2\varepsilon\).

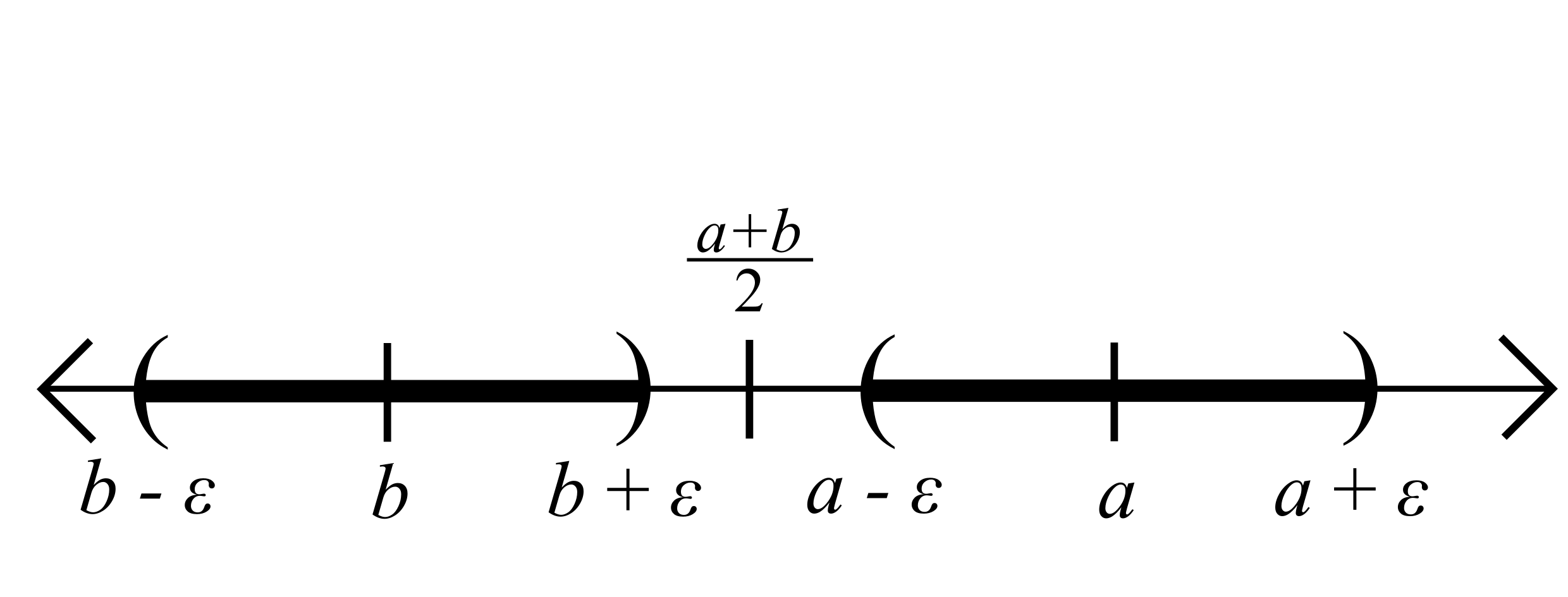

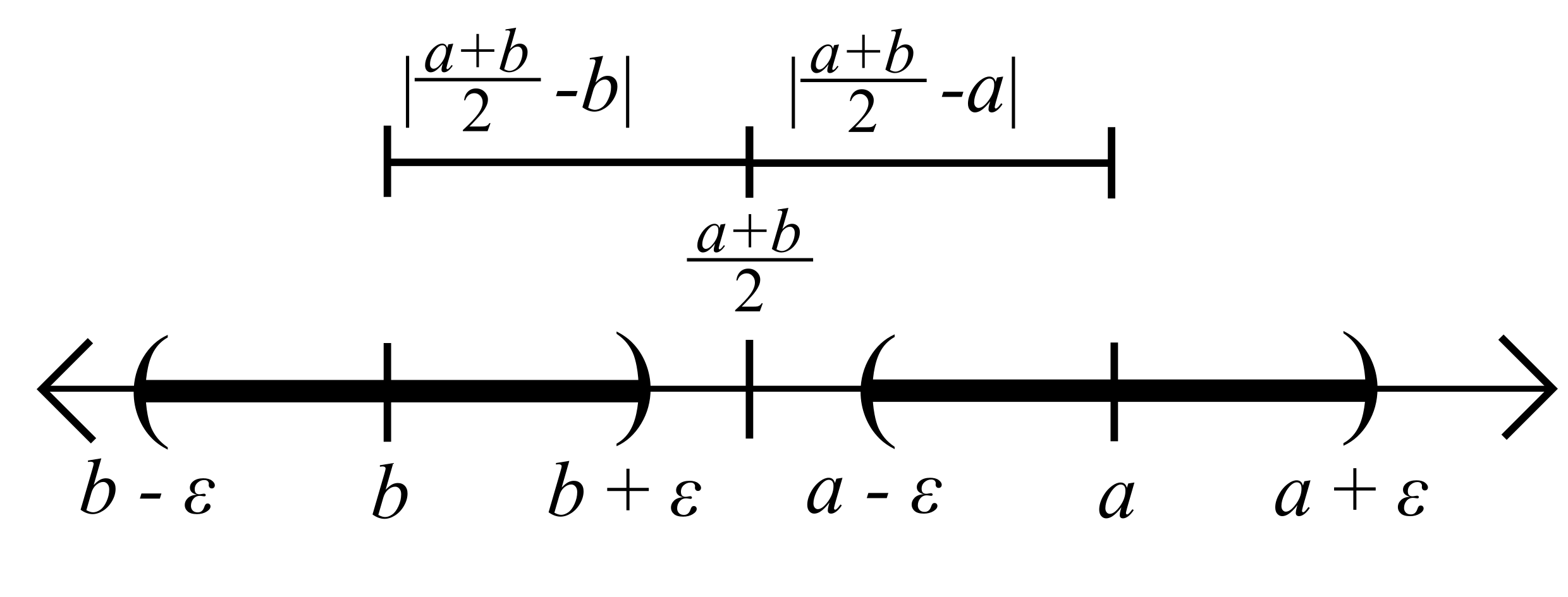

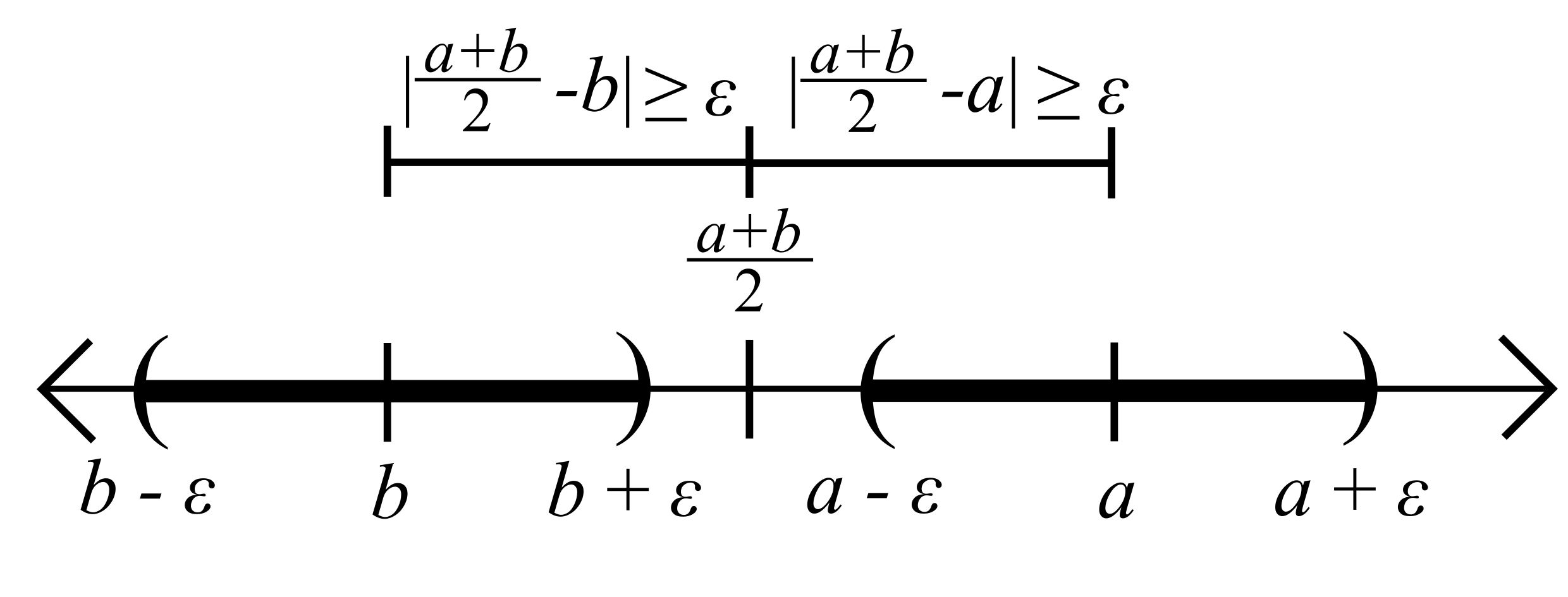

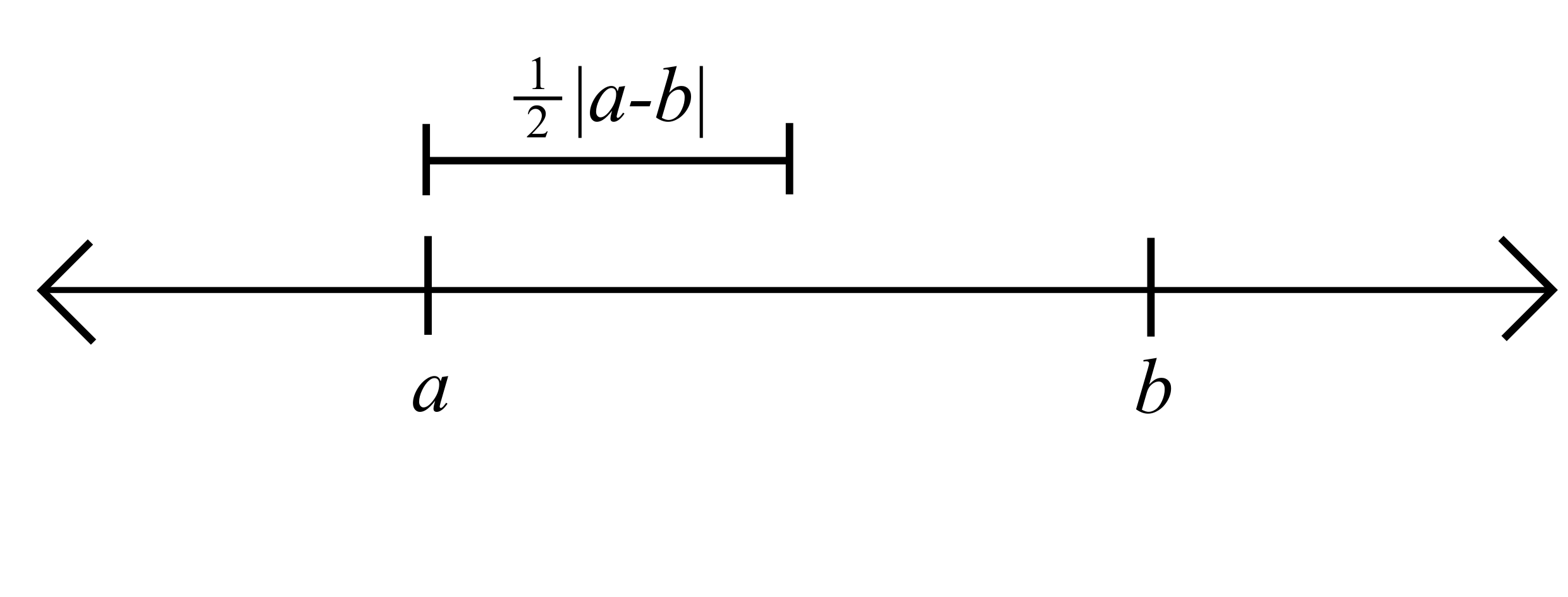

Proof. Assume \(V_{\varepsilon}(a)\cap V_{\varepsilon}(b) = \varnothing\). Set

\[c = \frac{a+b}{2}.\]

Note that

\[|a-c| = \left|a-\frac{a+b}{2}\right| = \left|\frac{a-b}{2}\right| = \frac{1}{2}|a-b|,\]

and

\[|b-c| = \left|b-\frac{a+b}{2}\right| = \left|\frac{b-a}{2}\right| = \frac{1}{2}|a-b|.\]

Since \(c\) is not in both \(V_{\varepsilon}(a)\) and \(V_{\varepsilon}(b)\), it must be the case that either \(|a-c|\geq \varepsilon\) or \(|b-c|\geq \varepsilon\). In either case this implies \[\frac{1}{2}|a-b|\geq \varepsilon.\ \Box\]

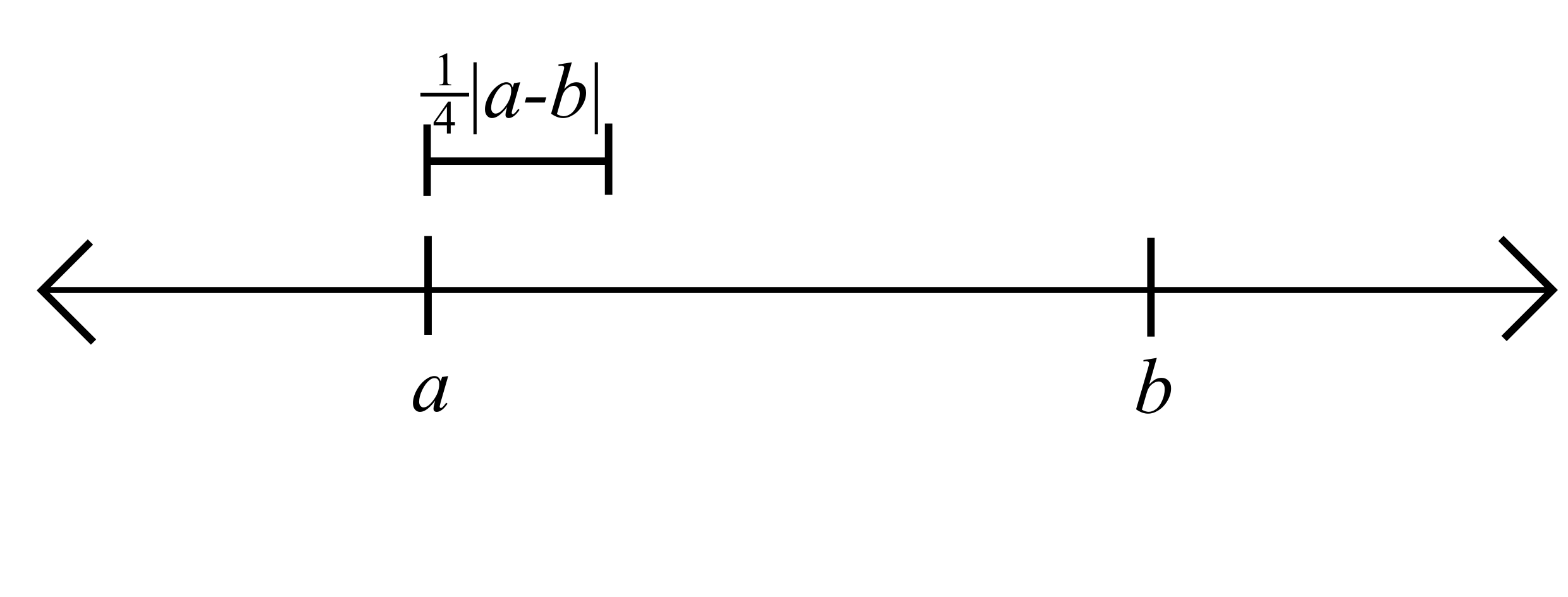

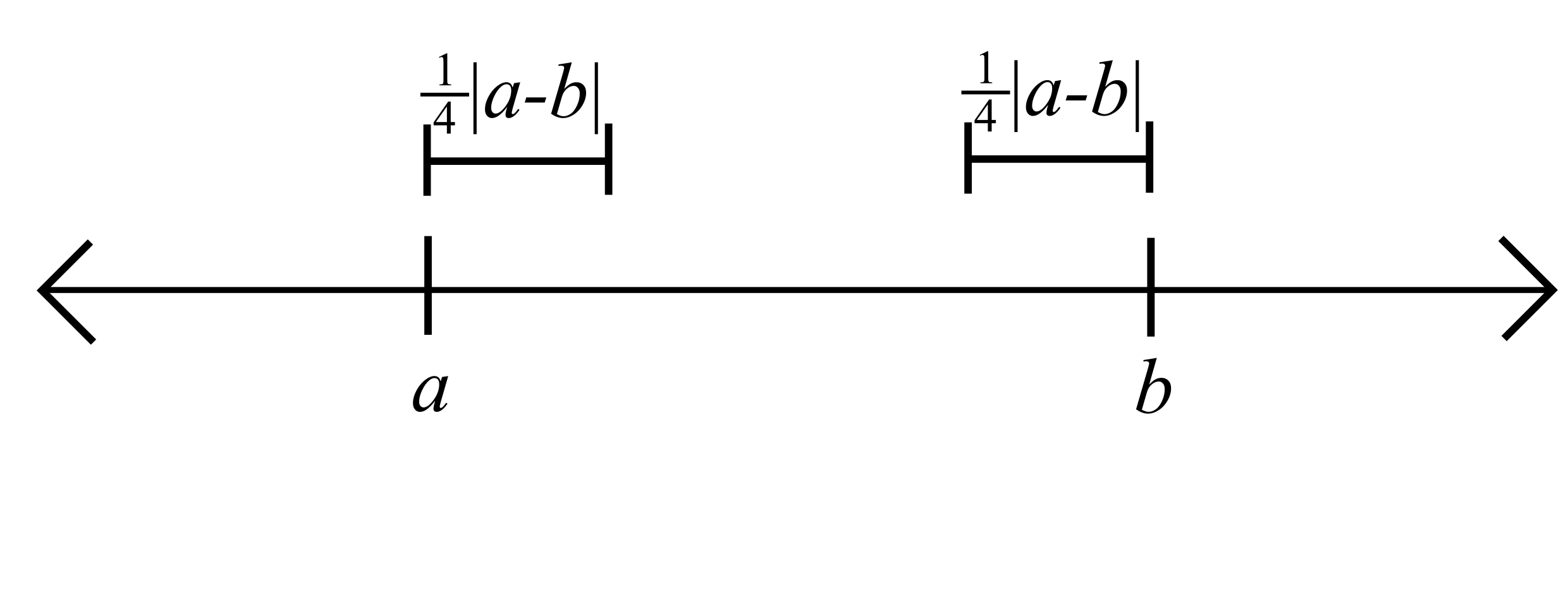

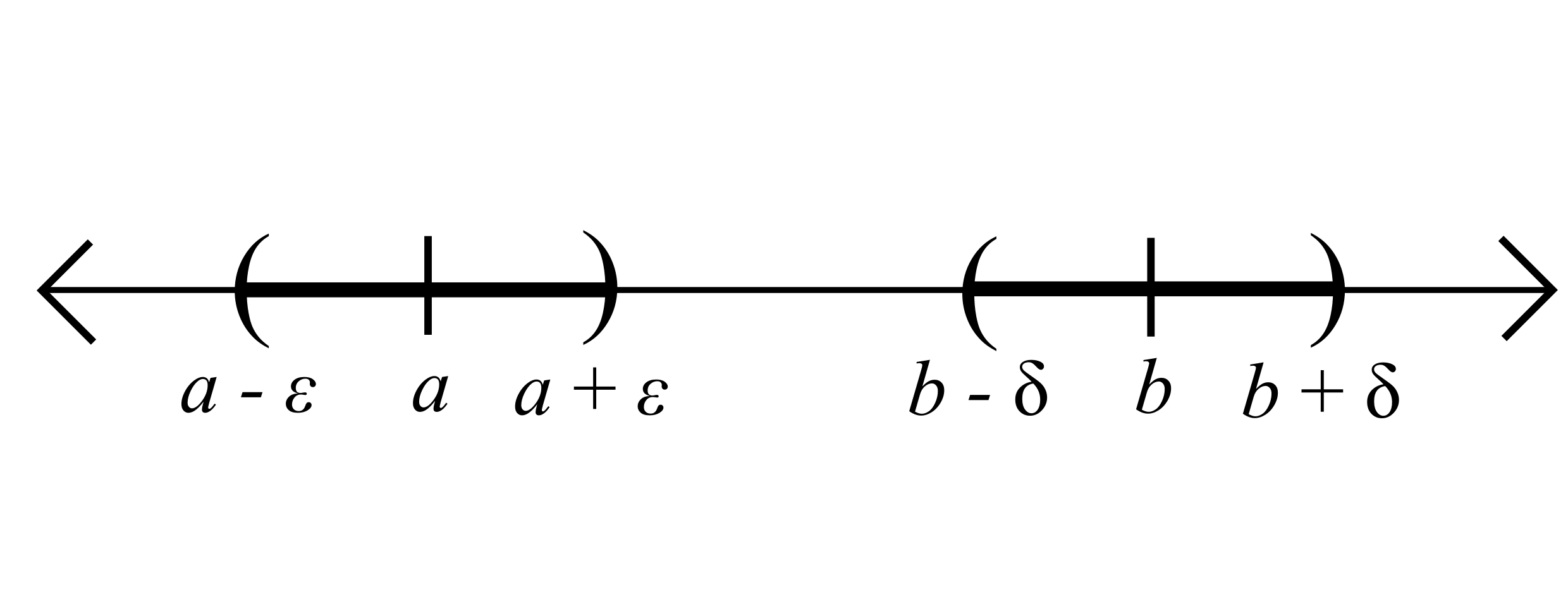

Proposition. If \(a\neq b\), then there are numbers \(\varepsilon>0\) and \(\delta>0\) such that \(V_{\varepsilon}(a)\cap V_{\delta}(b) = \varnothing\).

\(|x-b|>\frac{1}{2}|a-b|+\delta=\frac{3}{4}|a-b|>\delta\)

Take \(\varepsilon = \frac{1}{4}|a-b|\) and \(\delta = \frac{1}{4}|a-b|\)

Proposition. If \(a\neq b\), then there are numbers \(\varepsilon>0\) and \(\delta>0\) such that \(V_{\varepsilon}(a)\cap V_{\delta}(b) = \varnothing\).

Proof. Suppose \(a\) and \(b\) are real numbers with \(a\neq b\). Since \(a\neq b\) we have \(|a-b|>0\). Set

\[\varepsilon=\delta=\frac{1}{4}|a-b|.\]

Clearly \(\varepsilon>0\) and \(\delta>0\). We claim that \(V_{\varepsilon}(a)\cap V_{\delta}(b) = \varnothing\).

Suppose \(x\in V_{\varepsilon}(a)\). By definition \(|x-a|<\varepsilon\), which implies \[-|x-a|>-\varepsilon.\] By the reverse triangle inequalty

\[|x-b| = |(a-b)+(x-a)|\geq |a-b|-|x-a|\]

Hence, \(x\notin V_{\delta}(b)\). \(\Box\)

\[>|a-b|-\varepsilon = \frac{3}{4}|a-b|>\delta.\]

Practice problem:

Prove the last proposition, but with \(\varepsilon=\delta=\frac{1}{2}|a-b|\).

End Lecture 8

Read Section 2.3

Proof. Suppose \(a\) and \(b\) are real numbers with \(a\neq b\). Since \(a\neq b\) we have \(|a-b|>0\). Set

\[\varepsilon=\delta=\frac{1}{2}|a-b|.\]

Clearly \(\varepsilon>0\) and \(\delta>0\). We claim that \(V_{\varepsilon}(a)\cap V_{\delta}(b) = \varnothing\).

Suppose \(x\in V_{\varepsilon}(a)\). By definition \(|x-a|<\varepsilon\), which implies \[-|x-a|>-\varepsilon.\] By the reverse triangle inequalty

\[|x-b| = |(a-b)+(x-a)|\geq |a-b|-|x-a|\]

Hence, \(x\notin V_{\delta}(b)\). \(\Box\)

\[>|a-b|-\varepsilon = \frac{1}{2}|a-b|=\delta.\]

End Lecture 8