Multimodal Data Fusion and Behavioral Analysis Tooling for Exploring Trust, Trust-propensity, and Phishing Victimization in Online Environments

Matt Hale

Assistant Professor of Cybersecurity

Nebraska University Center for Information Assurance

Mickey Hefley, Gabi Wethor, Matthew L. Hale

HICSS-51 2018, Waikoloa, HI

Slides available at: slides.mlhale.com/hicss2018/

Today: Answering Four Questions

What's the state of phishing? (context)

What are we doing about it? (contribution)

Is it performant? (evaluation)

Is it precise? (evaluation)

Bonus Question:

Who is this guy?

Dog Father, Husband, Software Engineer, Researcher, Teacher, Web Developer, Board Gamer, Philosopher, Artist

(roughly in that order)

Tweet @mlhale_

Two Main Research Areas:

Internet of Things Security and Phishing Prevention

Two Main Research Areas:

Internet of Things Security and Phishing Prevention

Today's Focus

STOP.

Look Around at Your Neighbors

What IF I told you...

...the most sophisticated phishing websites would dupe about half (45%) of the people around you. Even average, less sophisticated, sites manage to convince more than 1 in 10 (13.7%).

More Numbers

60 billion

6 billion

3 billion

28 million

164 million

16.5 Million

8.2 Million

100,000

http://services.google.com/fh/files/blogs/google_hijacking_study_2014.pdf https://www.getcybersafe.gc.ca/cnt/rsrcs/nfgrphcs/nfgrphcs-2012-10-11-en.aspx

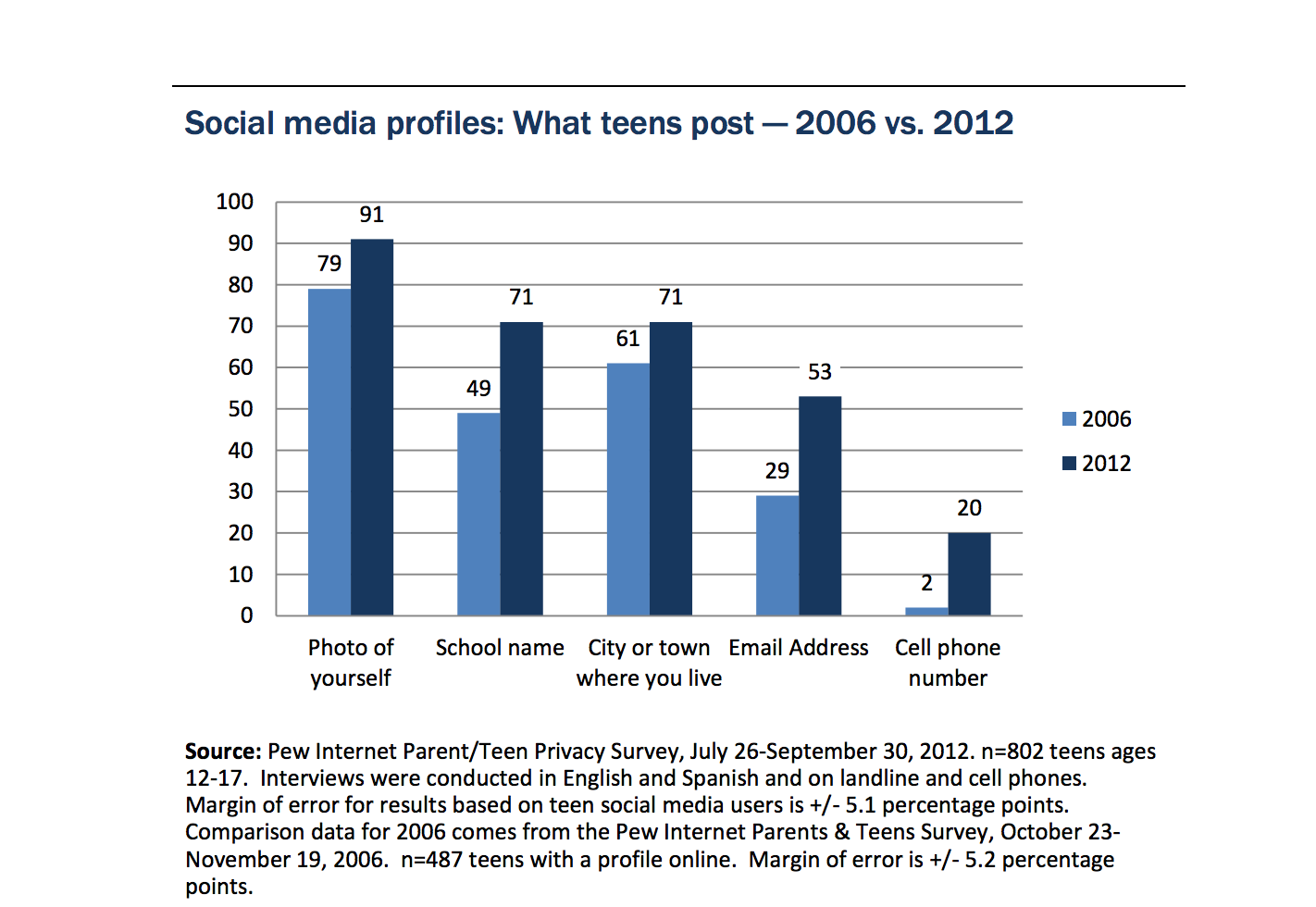

The numbers are likely to Increase...

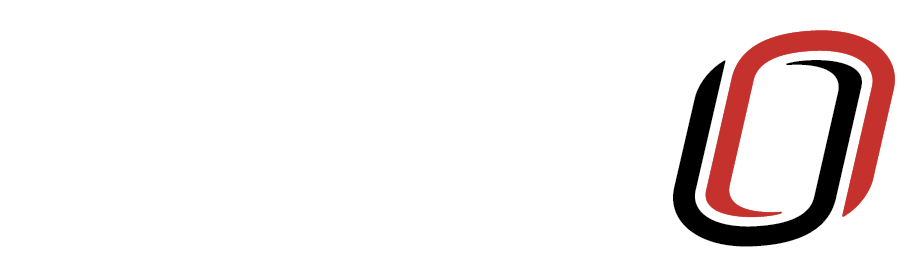

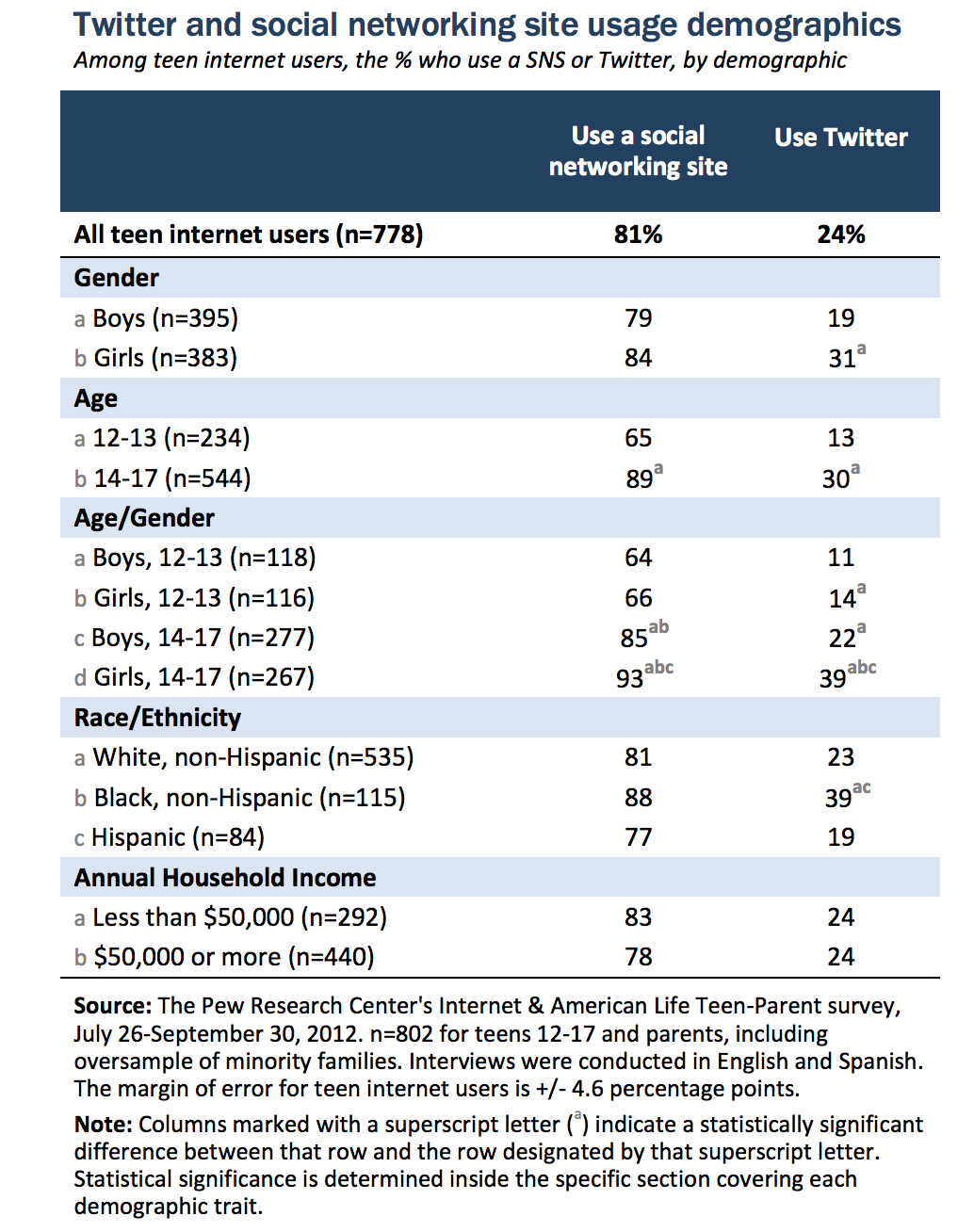

Sources: http://www.pewinternet.org/files/2013/05/PIP_TeensSocialMediaandPrivacy_PDF.pdf

Digital Citizenship is an INcreasingly Salient Issue for our society

Sources: http://www.pewinternet.org/files/2013/05/PIP_TeensSocialMediaandPrivacy_PDF.pdf

Easier than Ever to Be an Attacker

(https://pipl.com/) Easily find personal information

(http://geosocialfootprint.com/) See a history of where you've been

(https://github.com/trustedsec/social-engineer-toolkit) Clone a legitmate site and install an information harvester in 2 steps

(sites not listed) Buy credit cards and SSNs for a few bucks

Enter the CyberTrust Platform

Cybertrust Project

(Preventing Phishing Victimization using Bio-behavioral Markers of Cyber Trust)

Investigating what trust factors influence decision making with suspicious content

Some of this material is based on research sponsored in part by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research (AFOSR), under award number FA9550-12-1-0457. The U.S. Government is authorized to reproduce and distribute reprints for Governmental purposes notwithstanding any copyright notation thereon. The views expressed in this talk are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defense or U.S. Government.

PRior Work Acknowledgement

Identify root causes of victimization

Identify user awareness gaps

Train participants to recognize suspicious content

Prevent victimization

Basic Idea

Instrumentation and Tooling

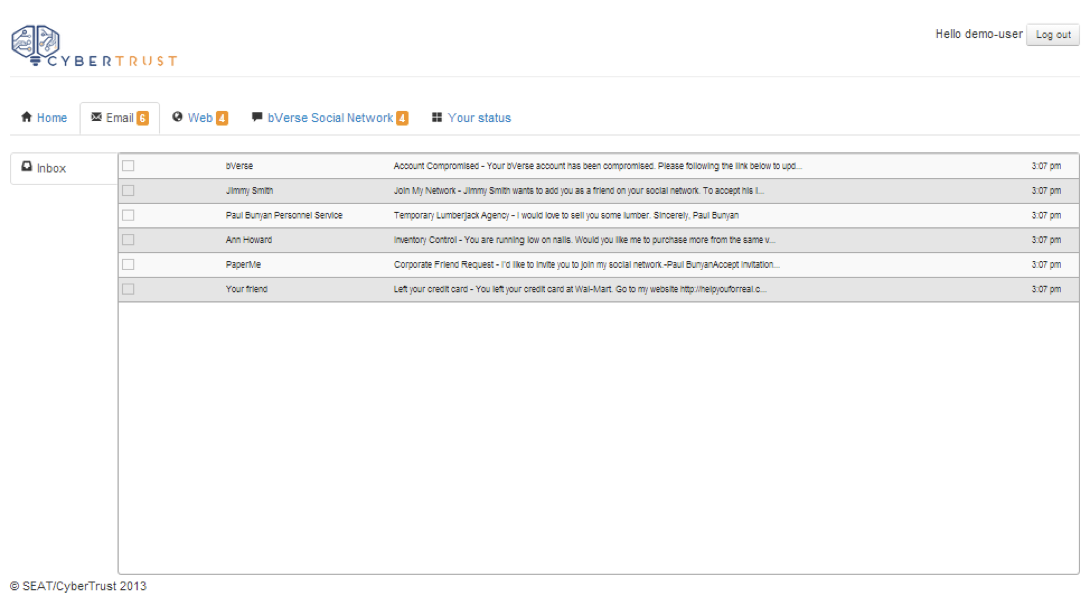

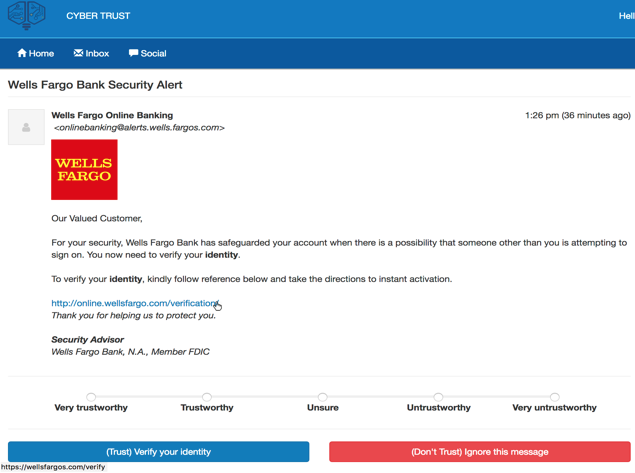

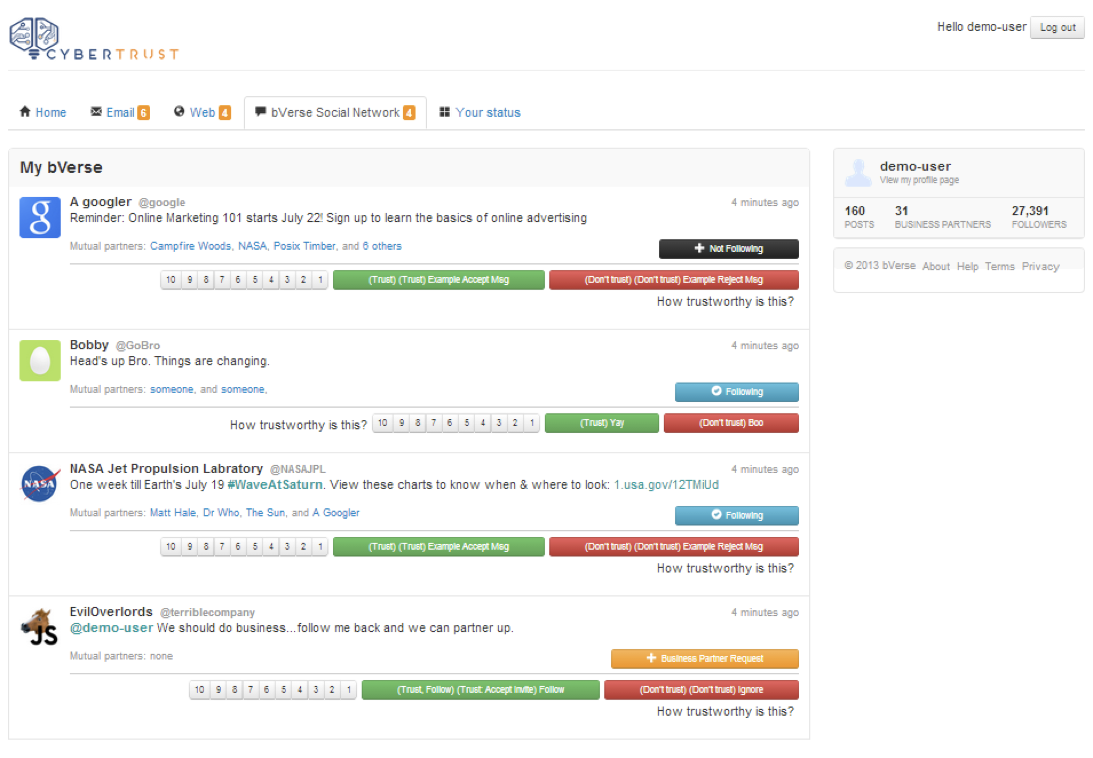

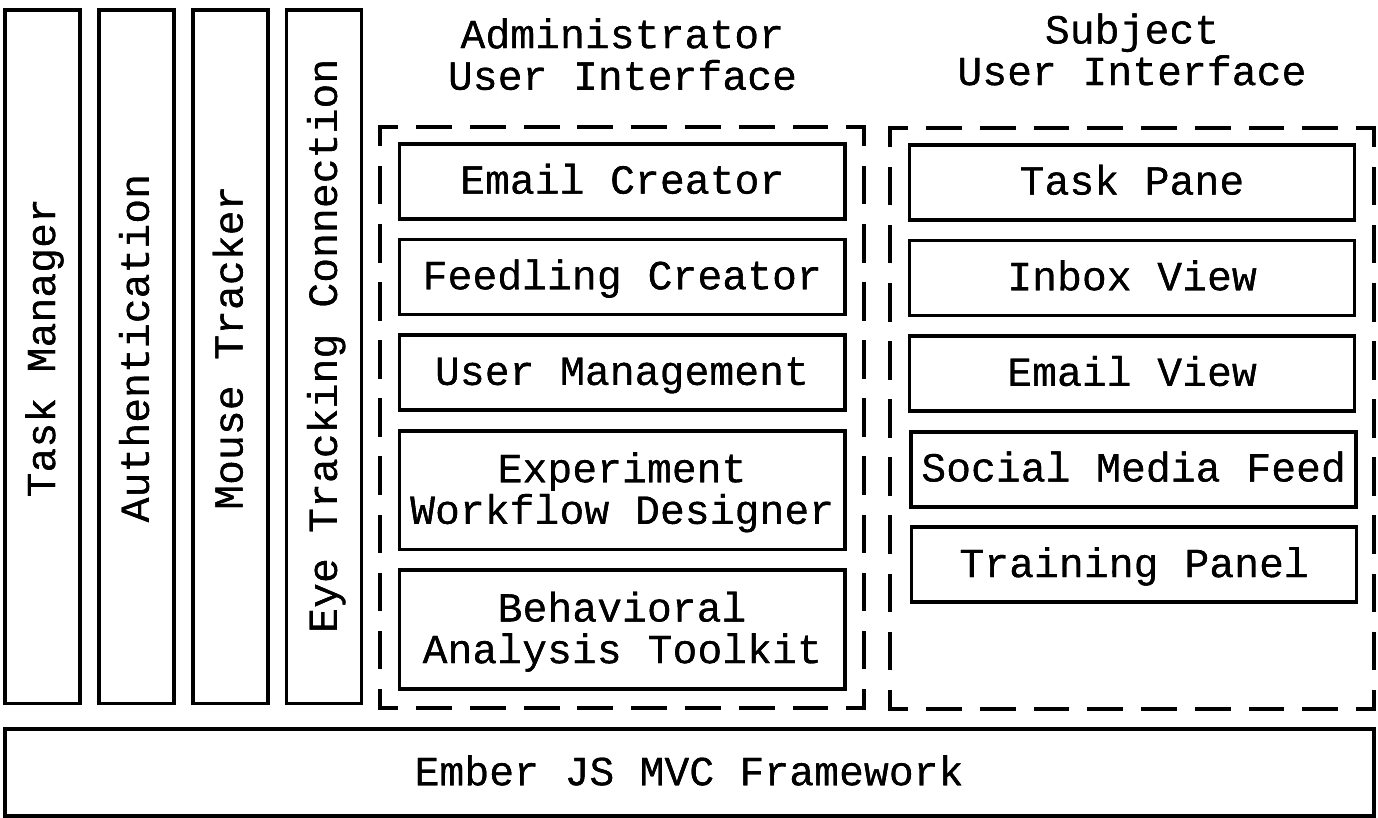

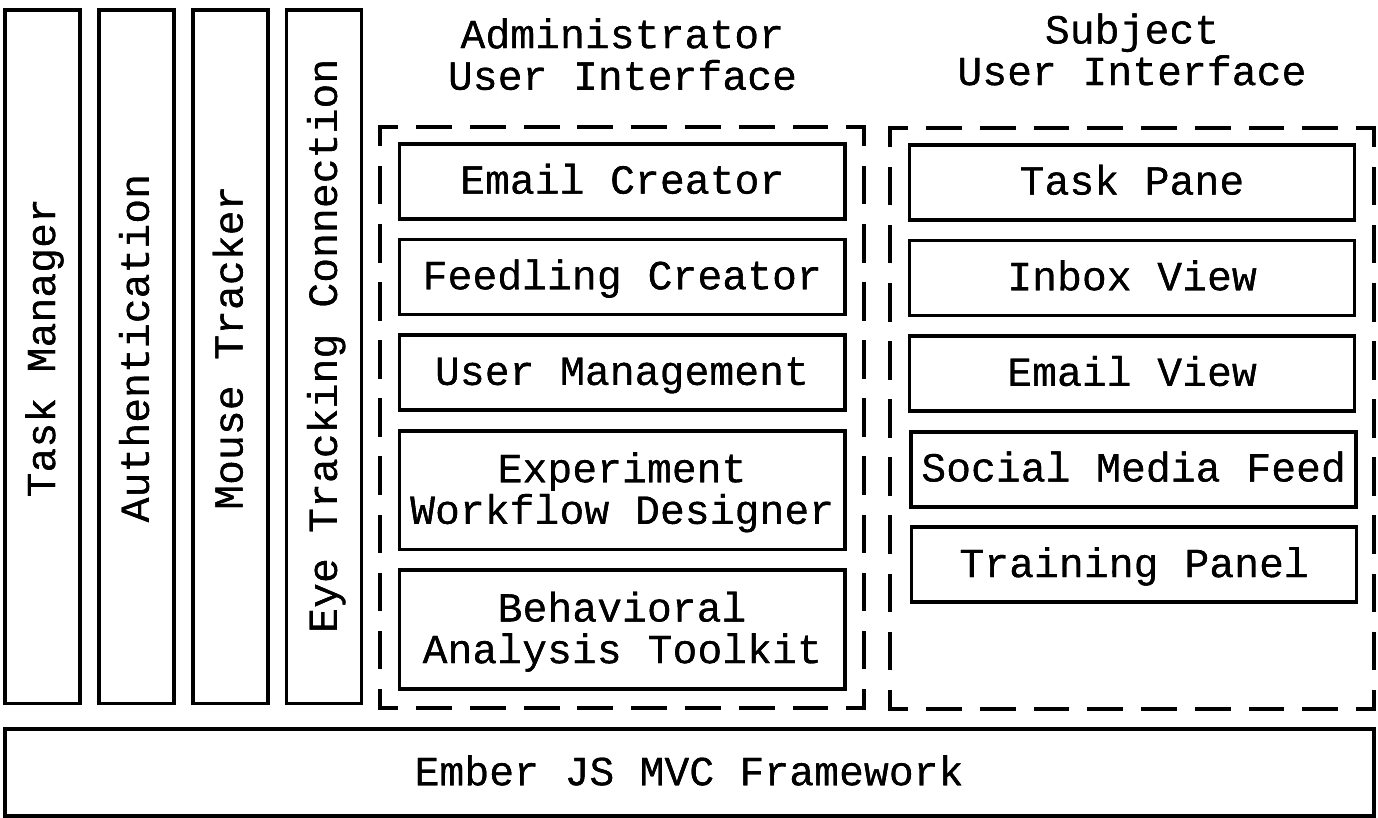

The Platform

The Platform

The Platform

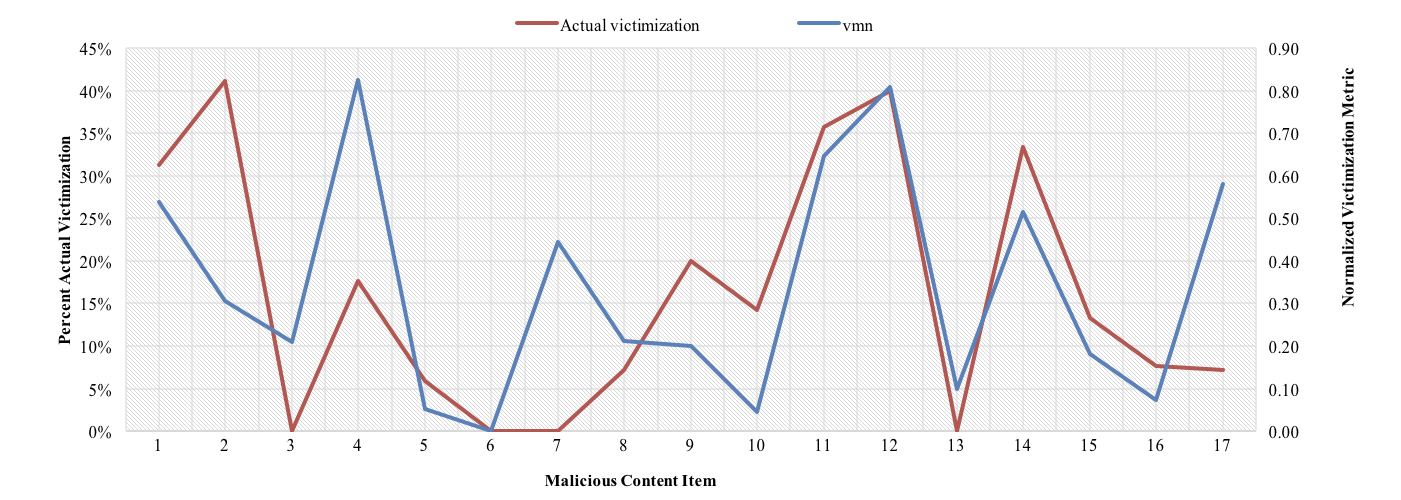

Previous Results:

predictor vs actual victimization

R=0.523, df=61, p=0.01

Ok, But Why am I here today?

Identify root causes of victimization

Identify user awareness gaps

Train participants to recognize suspicious content

Prevent victimization

Basic Idea

Instrumentation and Tooling

MULTIMODAL DATA FUSION AND BEHAVIORAL ANALYSIS TOOLING FOR EXPLORING TRUST, TRUST-PROPENSITY, AND PHISHING VICTIMIZATION IN ONLINE ENVIRONMENTS

HICSS 2018 Paper Contribution

So...That title is a mouthful

MULTIMODAL DATA FUSION AND BEHAVIORAL ANALYSIS TOOLING FOR EXPLORING TRUST, TRUST-PROPENSITY, AND PHISHING VICTIMIZATION IN ONLINE ENVIRONMENTS

Breaking it down

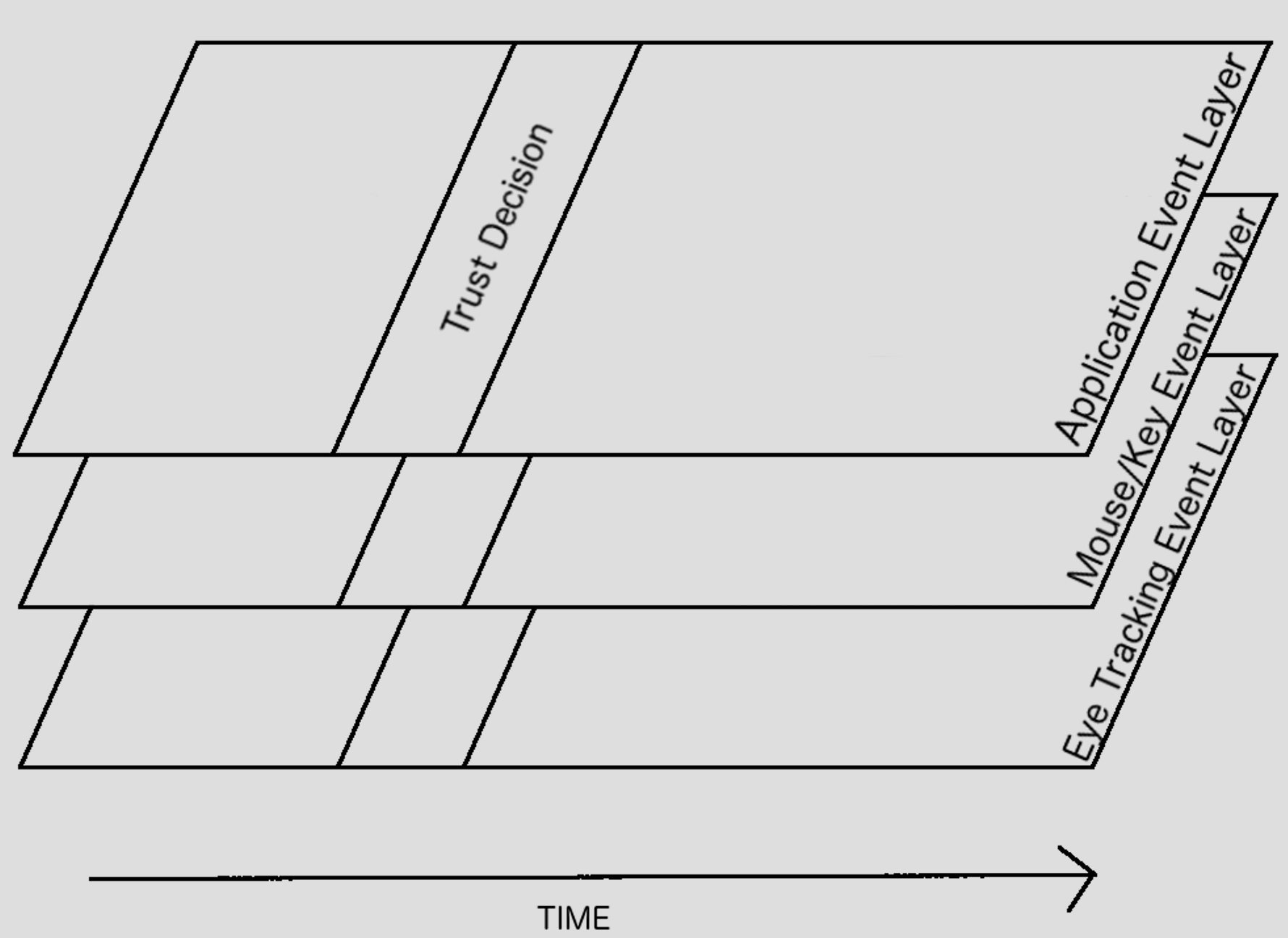

Multiple types of data: Eye tracker, mouse movement, keypresses, and application data (macro level behaviors)

MULTIMODAL DATA FUSION AND BEHAVIORAL ANALYSIS TOOLING FOR EXPLORING TRUST, TRUST-PROPENSITY, AND PHISHING VICTIMIZATION IN ONLINE ENVIRONMENTS

Breaking it down

Stitching the various data together to present a picture that is more than the sum of its parts

MULTIMODAL DATA FUSION AND BEHAVIORAL ANALYSIS TOOLING FOR EXPLORING TRUST, TRUST-PROPENSITY, AND PHISHING VICTIMIZATION IN ONLINE ENVIRONMENTS

Breaking it down

The data alone is not enough, we want to understand how users behave and how behaviors lead to the creation of capturable data artifacts

MULTIMODAL DATA FUSION AND BEHAVIORAL ANALYSIS TOOLING FOR EXPLORING TRUST, TRUST-PROPENSITY, AND PHISHING VICTIMIZATION IN ONLINE ENVIRONMENTS

Breaking it down

The point. We envision a tool that can help researchers better understand behaviors that lead to phishing victimization - so they can develop better training tools to prevent them.

More than a Title:

Our Contribution

New Tooling for Behavioral Analysis

(Software Architecture)

New Tooling for Behavioral Analysis

(Software Architecture)

New Tooling for Behavioral Analysis

(Software Architecture)

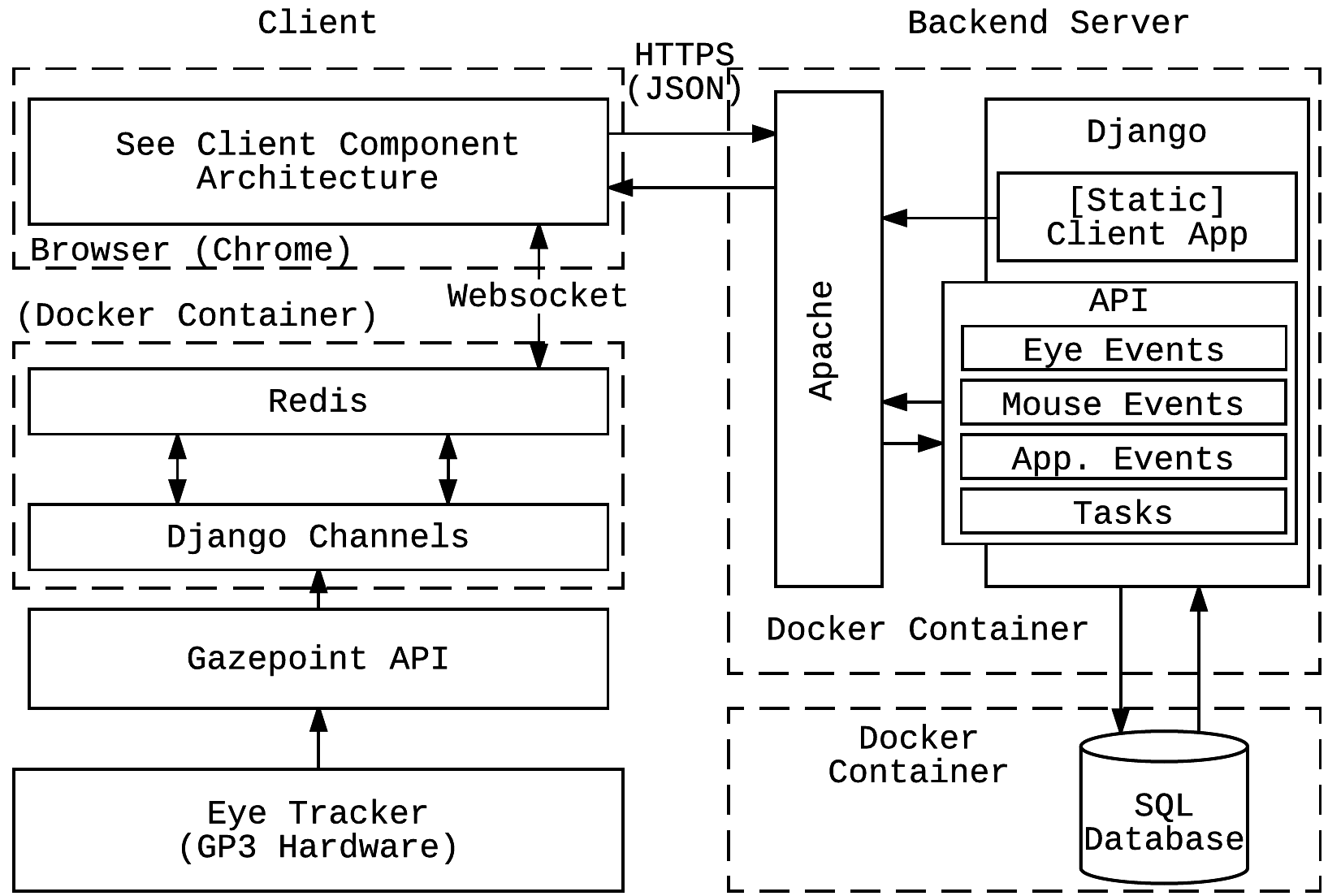

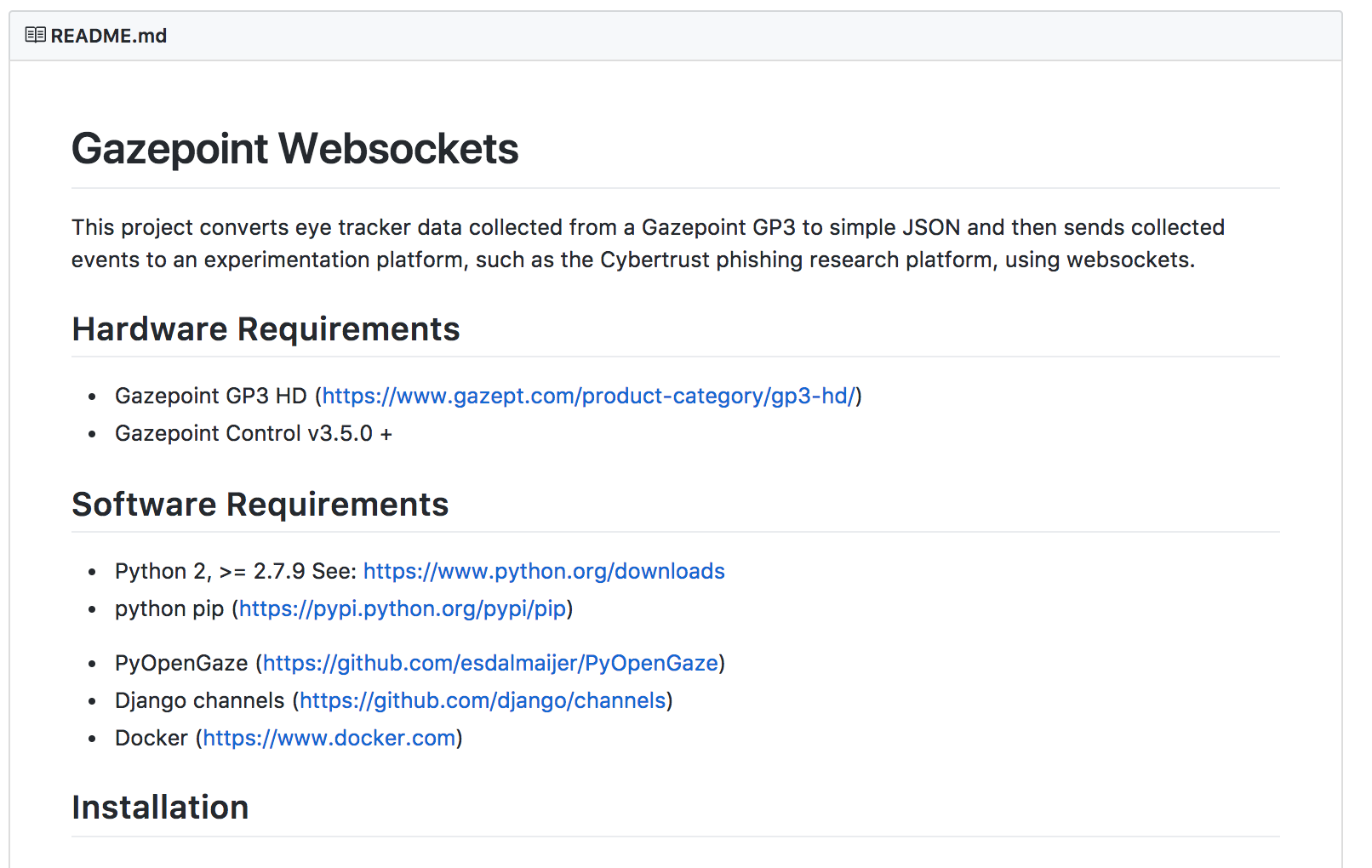

Our Approach

Works with the Gazepoint GP3 Eye Tracker

Photo credit GP3 Marketing materials (gazept.com)

Quick Tangent

More than Just CONVENIENT

- Docker makes our data capture techniques more modular and thus more scalable.

- It allows us to package everything required easing addoption and modularization in the open source community

Speaking of Open Source...

#End of Docker Tangent

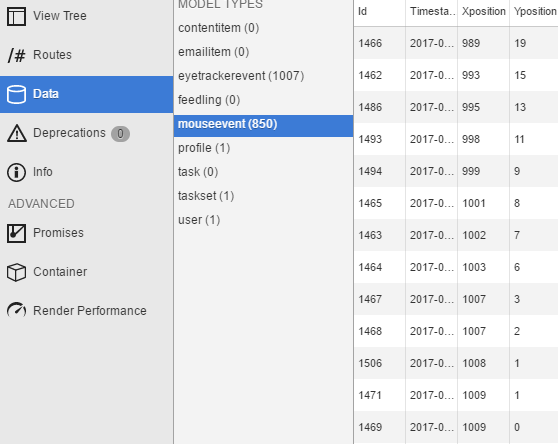

What Data is collected?

(Mouse data/Key data)

-

Mouse Movement: On a user mouse movement event, capture {x, y, w, h, t}, where x and y identify the pixel coordinates of the mouse, in two-dimensional screen space, x ≤ w and y ≤ h), w and h define the maximum screen size (in pixels), and t is the time when the mouse event occurred. uses the W3C standard high resolution time level 2 specification with worst-case resolvable timing skew of 5ms. Other mouse and keyboard events also use high res. timing.

-

Mouse Selection: On a user mouse up event, capture {ht, t} where ht is highlighted text and t is the high-resolution timestamp when the event occurred. If no text is highlighted this event is ignored.

-

Mouse Clicks: On user mouse down capture {x, y, w, h, t}. Similarly, to mouse movement, x and y define pixel positions in screen coordinate space, w and h define the max screen width and height, and t is the timestamp when the click event occurred.

-

Key Press: On a user key down event, capture {k, t}, where k is the Unicode character identifying the key pressed (as translated from its browser-specific keycode) and t is the time the event occurred

What Data is collected?

(eye movement data)

-

Eye Movement events are logged following the schema: {tid, cnt, et, t-tick, msg, cx, cy, fpogid, fpogd, fpogs, fpogv, fpogx, fpogy, bpogx, bpogy, bpogx, lpogx, lpogy, lpogv, rpogx, rpogy, rpogv leyex, leyey, leyez, lpupild, lpupilv, reyex, reyey, reyez, rpupild, rpupilv, lpcx, lpcy, lpd, lps, lpv, rpcx, rpcy, rpd, rps, rpv}

What Data is collected?

(macro "application level" behavioral data)

-

Session Timing: {sts, ste}, where sts and ste are high-resolution timestamps identifying the start and end times of the user’s session.

-

Time tracking (task): {tts, tte, tid}, where tts and tte are the start and end times that identify how long the user views content associated with the task, with id tid.

-

Likert scale: rates the trustworthiness of content as very trustworthy, trustworthy, unsure, untrustworthy, or very untrustworthy.

-

trust decision: {tid, lrt, tr}, where tid is the task id, lrt is trustworthiness captured by the Likert scale and tr is a Boolean indicating trust (true) or do not trust (false).

-

Idle time: When a user goes into an idle state, capture {it, et}. Where it and et are high resolution timestamps identifying the start and end times of user idling.

Data Fusion

Happens via web sockets and rest API calls

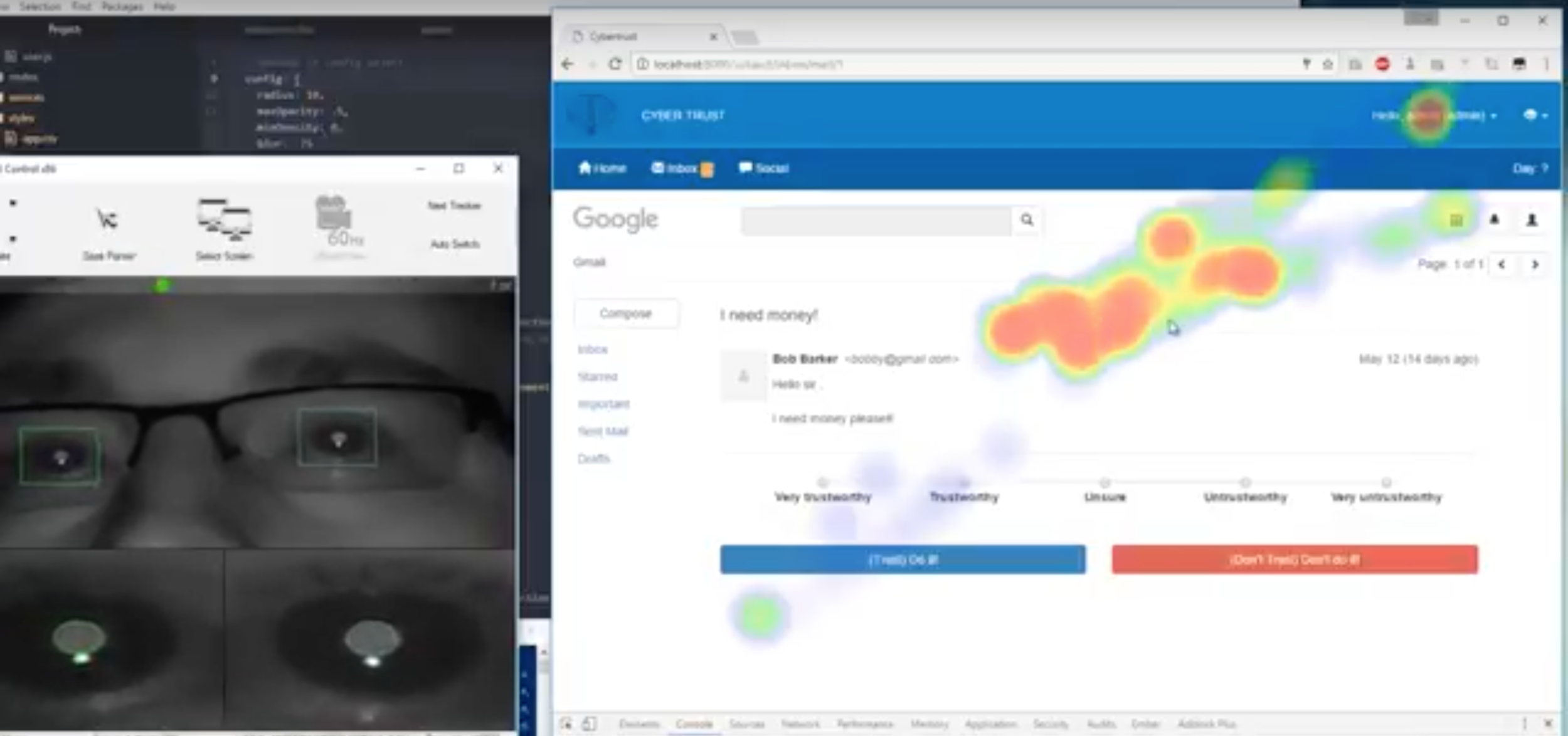

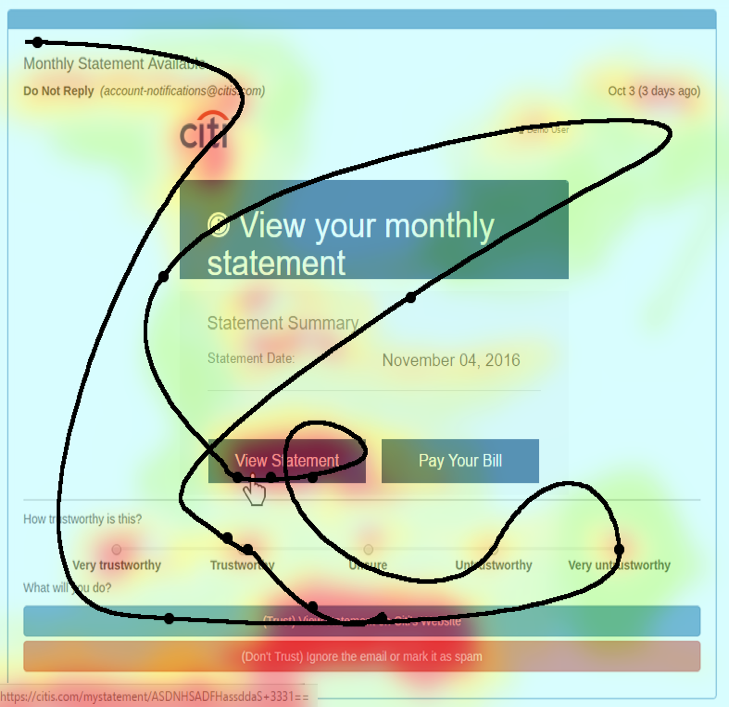

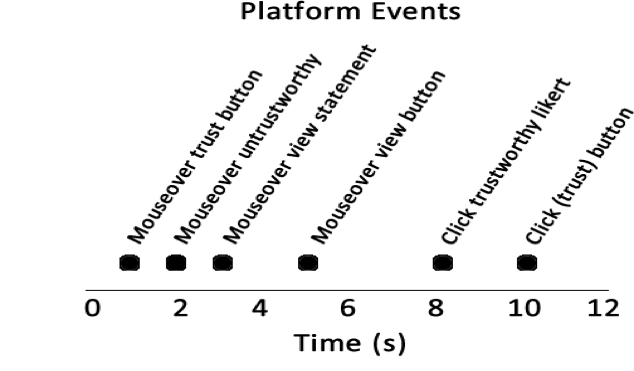

Towards Behavioral Analysis Tooling

Heatmap and event tracing component output allows researchers to reconstruct subject sessions.

(black line = mousing events)

Towards Behavioral Analysis Tooling

Can also be viewed as a time series

Ok, but is it performant?

Short Answer: Yes

Long Answer

- Criteria 1: The end-user test subject should not observe any performance hits during data collection and logging and they should be able to complete tasks (e.g. view and rate online content) unimpeded.

- Criteria 2: All captured data points collected during a subject’s session should be sent to, parsed, and stored by the backend data API server without loss.

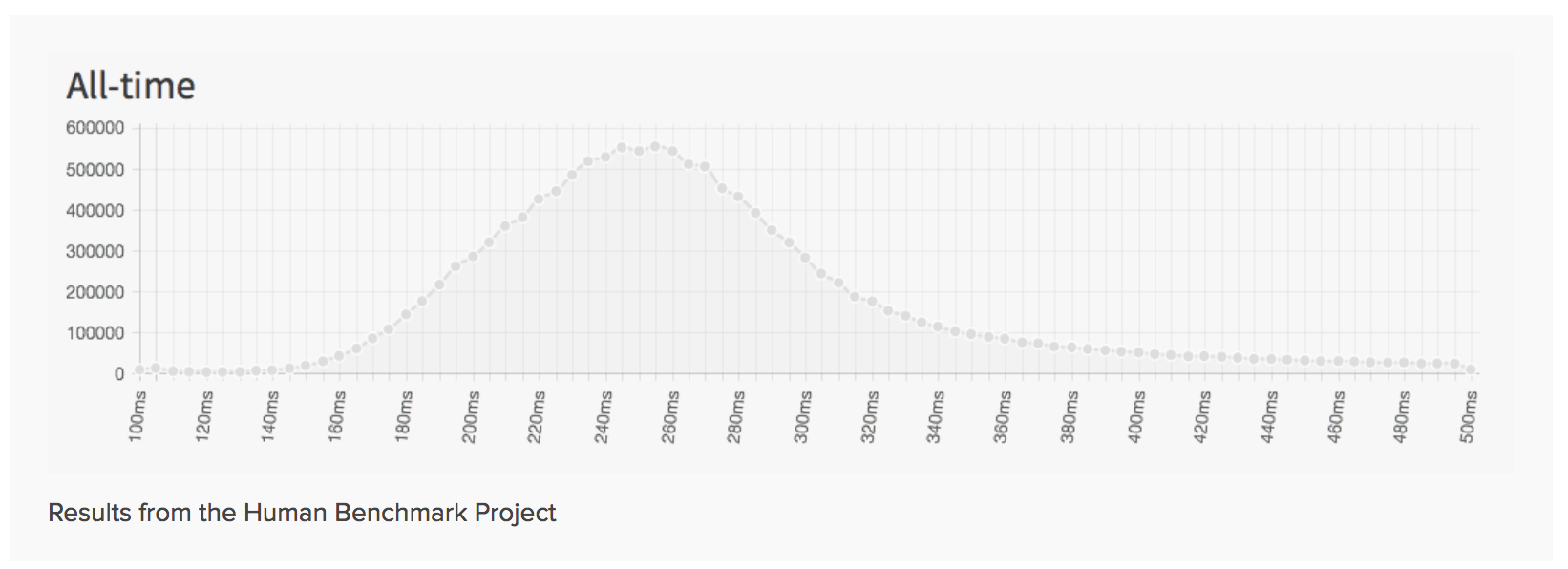

Long Answer

- Criteria 1: The end-user test subject should not observe any performance hits during data collection and logging and they should be able to complete tasks (e.g. view and rate online content) unimpeded.

- Tested as client response rate (ms)

- Ran 30 data capture sessions as users interacted with content in Cybertrust

Average Delay time Resulting from Data Capture: 68ms

Long Answer

This Meets Criteria 1. It is well below the average human response time.

Long Answer

- Criteria 2: All captured data points collected during a subject’s session should be sent to, parsed, and stored by the backend data API server without loss.

Long Answer

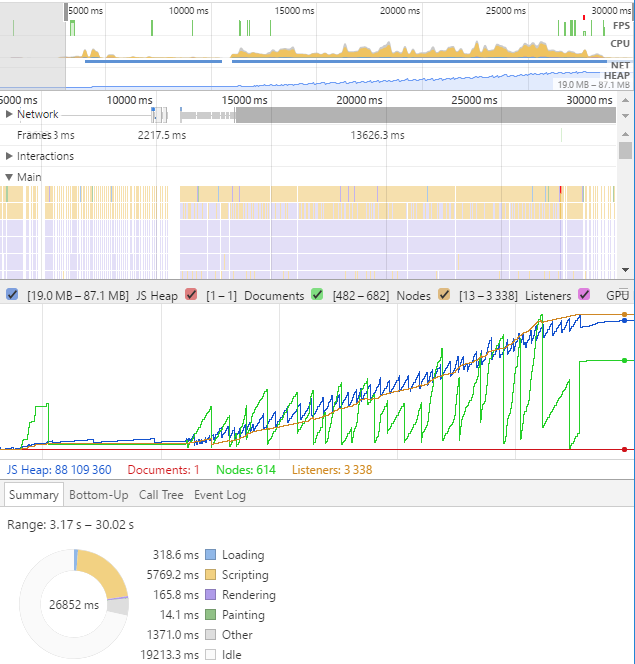

1 of the 30 client performance captures. While fps is high (criteria 1), heap size is growing as the number of events are logged. Also there are many network requests that eventually stack up and queue)

~4500 eye events and 2850 mouse events per 30 second task

Long Answer

- Criteria 2: All captured data points collected during a subject’s session should be sent to, parsed, and stored by the backend data API server without loss.

This violated Criteria 2.

Long Answer

- Criteria 2: All captured data points collected during a subject’s session should be sent to, parsed, and stored by the backend data API server without loss.

We fixed this problem by introducing a batch commit strategy - reducing the heap size and eliminating network queing by sending more events to the server at once.

Long Answer

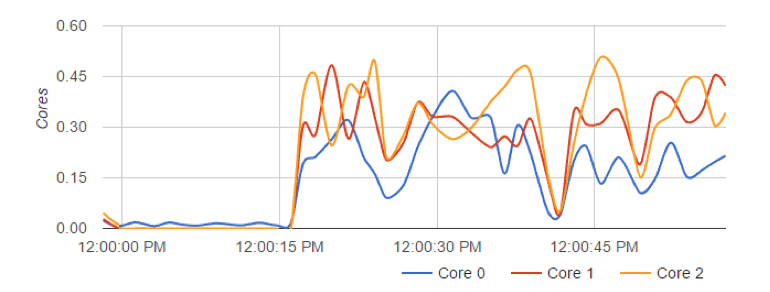

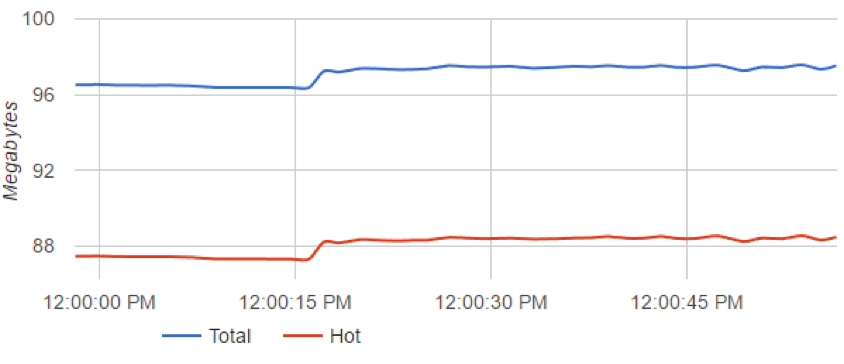

Web-socket server performance during 1 of the 30 captures shown in C-Advisor

Across the 30 tests, overall CPU utilization maxed out at 33% (at full simulated load) Ubuntu Server 16.04.2 on ESXi (pooled 4ghz CPU resources). Memory usage did not exceed 150MB and was, on average less than 100MB.

Is it Precise?

Precision Numbers

Mouse and Keyboard

Eye Tracker

Macro "Application Level"

800µs

333ns

5µs - 100ms

(by type)

Questions?

©2018 Matthew L. Hale or as listed

Matt Hale, PHD

University of Nebraska at Omaha

Assistant Professor, Cybersecurity

mlhale@unomaha.edu

twitter: @mlhale_