Workflow orchestration

SHODO

Hello! I'm Nathan.

- Co-founder of Shodo Lille

- Backend developer

- Pushing Go to production since 2014

- Worked 10 years at OVHcloud

- Inclusion & Diversity activist

- https://bento.me/nathan-castelein

What about you?

The next four hours

Schedule

Morning session

- 9h: Session start

- 10h: 5 minutes break

- 11h: 10 minutes break

- 12h: 5 minutes break

- 13h: Session ends

Afternoon session

- 14h: Session start

- 15h: 5 minutes break

- 16h: 10 minutes break

- 17h: 5 minutes break

- 18h: Session ends

What do you expect

from this training?

Content

- Workflow introduction

- Our project

- Choreography

- Orchestration

A four-hours training means ...

- A lot of resources will be provided to go further outside of the training session

- Some topics are excluded from this training session

- Sometimes, it's my point of view

- I'm available for any question following the session: nathan.castelein@shodo-lille.io

Prerequisites

- Go v1.22

- Visual Studio Code

- Git

Workflow introduction

What's a workflow?

A workflow is a process that contains 2 or more steps.

In the context of data engineering, a workflow could mean anything from simply moving data to spinning up infrastructure to triggering an operational process via API. In any of these cases, there are steps that need to happen in a certain order.

Do you have some examples of workflows?

Workflow examples

We are constantly using workflows in our day-to-day work:

- Order validation, payment and delivery

- Sending an email after account creation

- Starting installation process after spawning a virtual machine

- Renew and bill customer's services each month

- ...

My love for workflows

Workflows management always has been crucial to my job at OVH:

- l1::Todo & todo.pl

- megatron

- megotron

- gigotron

- ...

But workflows management also always has been an underrated topic for me.

Until four years ago when I started going deeper on the topic!

Understanding workflows management complexity

If workflows are just a couple of steps to execute in order, why is it a such complex topic?

Let's work with an example.

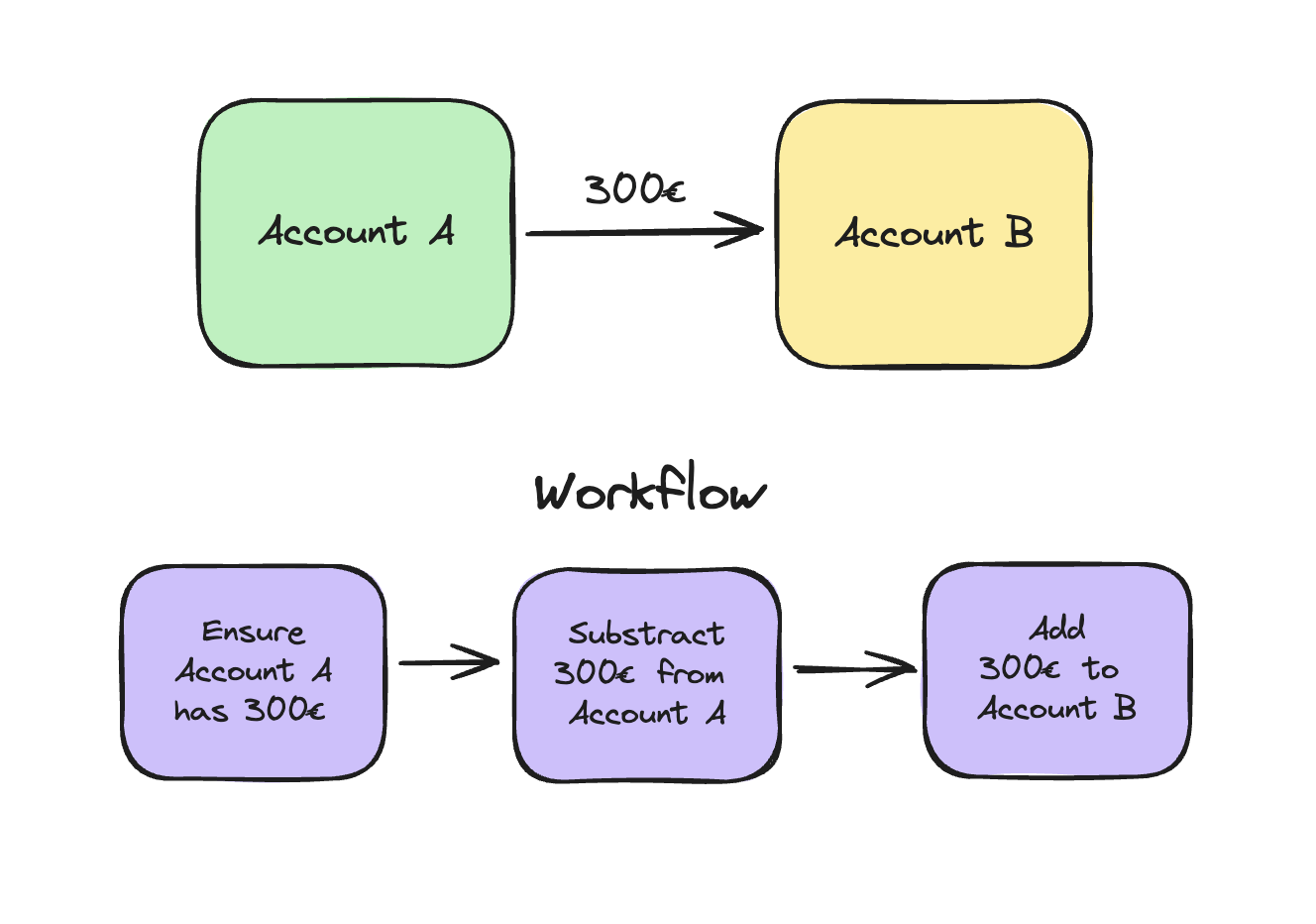

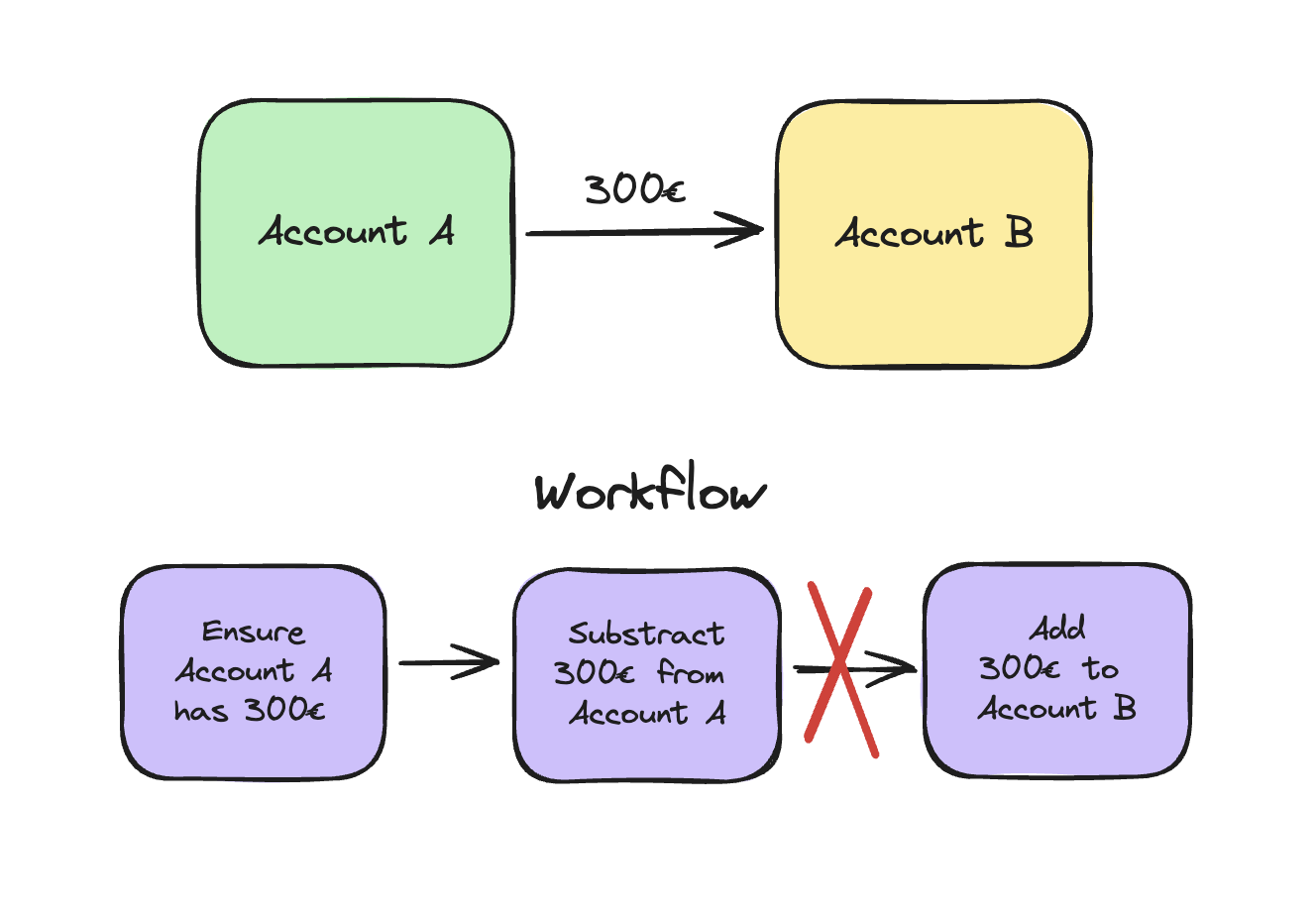

Moving money

Imagine an issue during workflow execution

Back to old times

Let's go back in time a bit, when softwares were monoliths on a single database.

There was a simple way to handle workflows: with a database transaction!

Let's have a look on this topic.

Database transaction

A database transaction is a sequence of multiple operations performed on a database, and all served as a single logical unit of work — taking place wholly or not at all.

If your database is running a transaction as one whole atomic unit, and the system fails due to a power outage, the transaction can be undone, reverting your database to its original state.

Transaction key features - Meet ACID

- Atomicity: ensures the transaction is treated as a single, indivisible unit, which either succeeds completely, or fails completely.

- Consistency: ensures a transaction brings the database from one valid state to another.

- Isolation: ensures the concurrent execution of transactions results in a system state that would be obtained if transactions were executed serially.

- Durability: ensures that once a transaction has been committed, it will remain committed even in the case of a system failure.

Database transaction limits

Database transactions exist!

Let's just put our workflow inside a transaction and it's done, no need for extra stuff?

But it looks like...we don't live in a single application/single database world!

In a distributed ecosystem, with microservices, local database transactions is not possible anymore.

Distributed ecosystem

In a distributed ecosystem, we still want to ensure the ACID principles.

In case of system failures in one or multiple microservices, we want the possibility to rollback the work already done, or to restart at the point of failure.

There's a pattern to handle this requirement: the SAGA pattern.

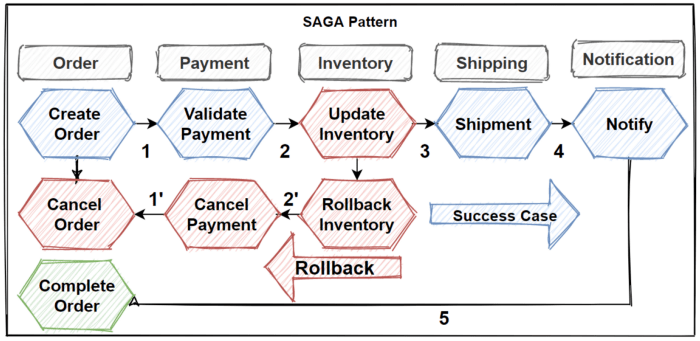

The SAGA pattern

The SAGA pattern

The Saga architecture pattern provides transaction management using a sequence of local transactions.

Every individual local transaction in the flow, utilizes ACID to update the local database.

In the event of a local transaction failure, the Saga performs a sequence of compensating transactions designed to revert the changes made by the preceding successful local transactions.

The SAGA pattern

The SAGA pattern

Sagas can be implemented in “two ways” primarily based on the logic that coordinates the steps of the Saga:

- Choreography based sagas: a local transaction publishes events that trigger other participants to execute local transactions

- Orchestration based sagas: a centralized saga orchestrator sends command messages to saga participants telling them to execute local transactions

The SAGA pattern

Let's now have a look on choreography and orchestration!

Our project

Our project

During this workshop, we will work on a workflow with different approaches to understand the complexity of workflows management with a simple example.

Let's go back in time!

Our project

Capturing Mewtwo

Catching a new Pokémon can be really tricky. There's a couple of steps to follow before throwing your pokéball:

- Paralyze the Pokémon

- Weaken the Pokémon

- Then throw your Pokéball and cross your fingers!

Let's model this.

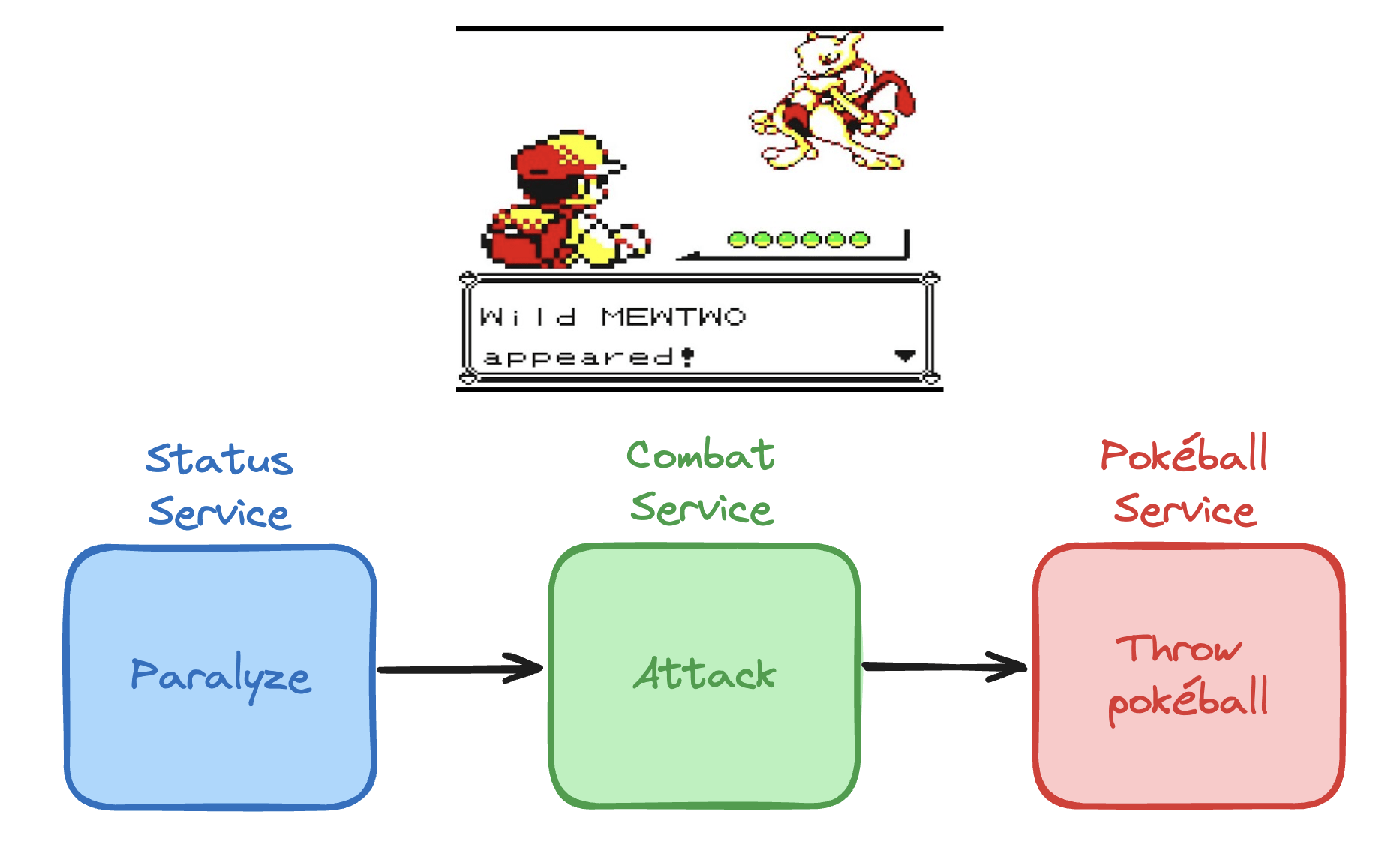

Capturing Mewtwo

Capturing Mewtwo

Our workflow is based on three different services:

- Status service

- Combat service

- Pokéball service

Each service is independent from the others, and managed by different teams.

We are in charge to build a workflow on top of this, to ensure the process will be managed from start to end.

Status service

const (

StatusParalyzed Status = "PAR"

StatusHealthy Status = "HEALTHY"

)

type StatusService interface {

Paralyze(pokemon *Pokemon) error

}

func NewStatusService() StatusService {

// ...

}Combat service

type CombatService interface {

Attack(pokemon *Pokemon) error

}

func NewCombatService() CombatService {

// ...

}Pokéball Service

type PokeballService interface {

Throw(trainer *Trainer, pokemon *Pokemon) error

}

func NewPokeballService() PokeballService {

// ...

}Pokémon

type Pokemon struct {

ID int

Name string

Level int

CurrentHealth int

MaxHealth int

Status Status

TrainerName string

}

func Mewtwo() *Pokemon {

return &Pokemon{

ID: rand.IntN(10000),

Name: "Mewtwo",

Level: 50,

CurrentHealth: 200,

MaxHealth: 200,

Status: StatusHealthy,

}

}

func Pikachu() *Pokemon {

return &Pokemon{

ID: rand.IntN(10000),

Name: "Pikachu",

Level: 60,

CurrentHealth: 230,

MaxHealth: 230,

Status: StatusHealthy,

}

}Trainer

type Trainer struct {

ID int

Name string

Pokemons []*Pokemon

}

func Sacha() *Trainer {

return &Trainer{

ID: rand.IntN(10000),

Name: "Sacha",

Pokemons: []*Pokemon{Pikachu()},

}

}Without workflow management

Let's have a look to a sequential implementation of the workflow:

- sequential/captureProcess.go

- sequential/captureProcess_test.go

Probably we can rewrite this process using workflow management!

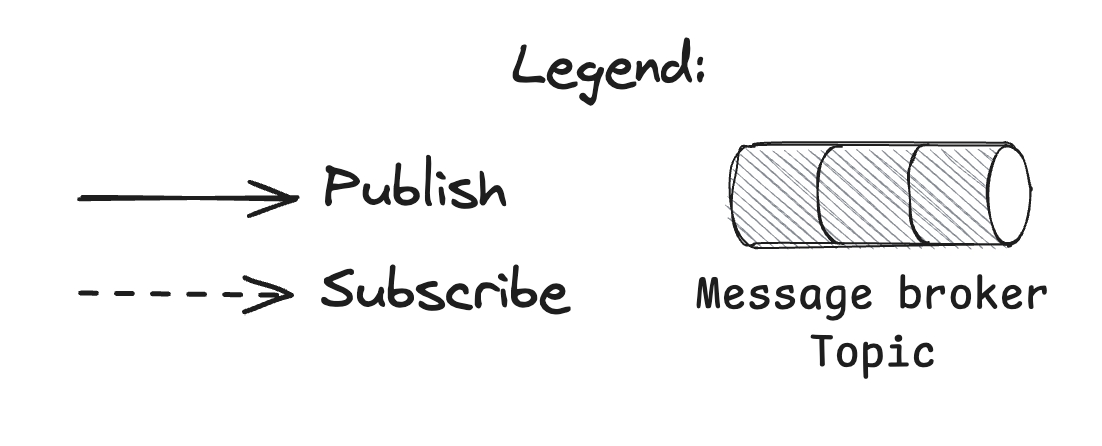

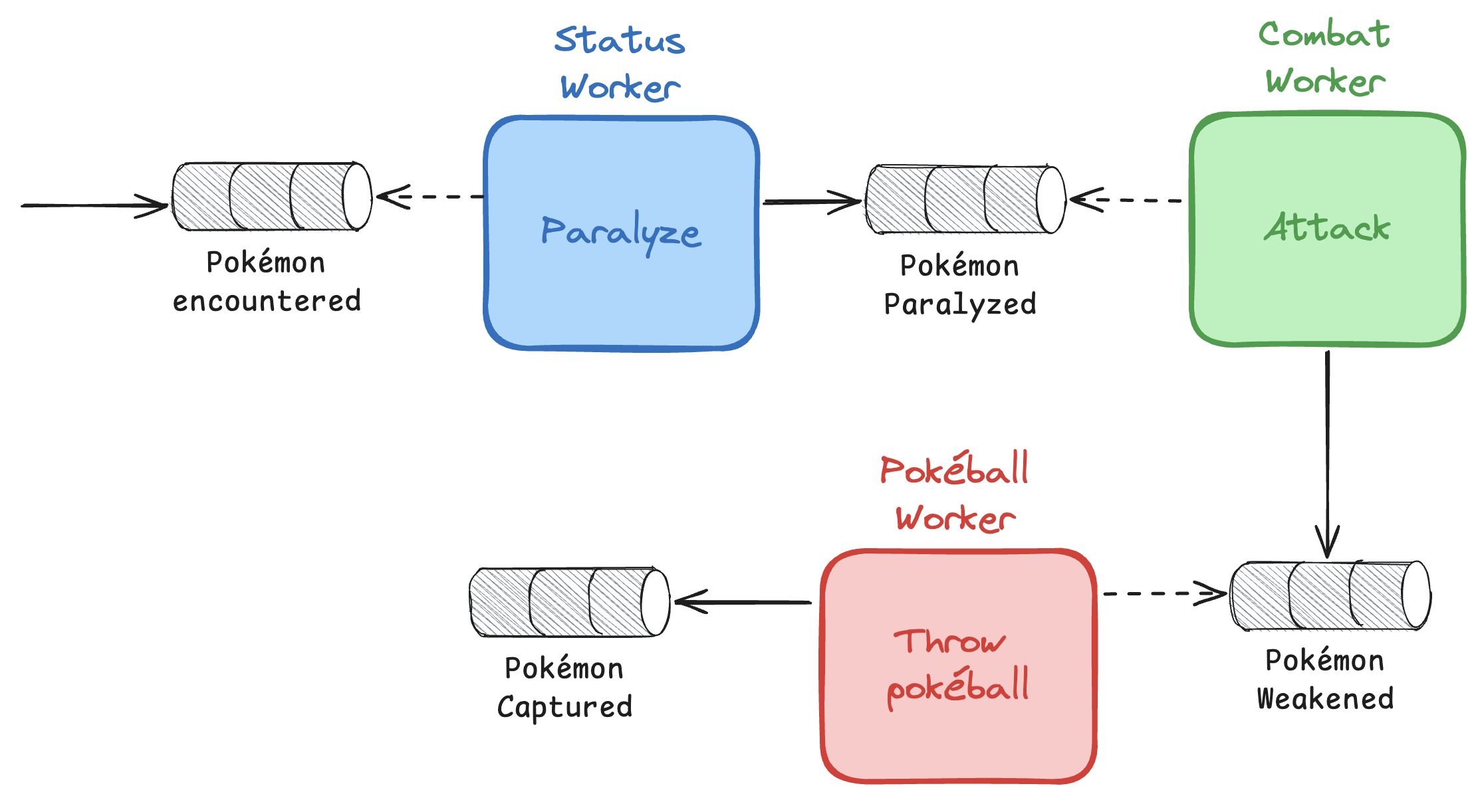

Choreography

Choreography

Let's now moving our sequential workflow to a more robust one, using the choreography pattern.

We will work with channels to simulate a message broker.

Choreography

Choreography

We will work on three workers, each responsible for a given service (status, combat, pokeball).

Each worker will subscribe to a defined topic, and will publish an event in another topic to start to the next step.

Benefits of choreography

With this given pattern, considering each service provides a transactional and atomic unity of work (paralyze, attack and throw pokéball), our application becomes more robust and resilient.

Message broker and topics ensure each step is done and restart properly in case of interruption. Each worker must:

- Read an event

- Do its work

- Ack the event

The Status Worker

Let's start with our first worker, the Status Worker!

File to open:

choreography/exercise1.mdThe Status worker

type StatusWorker struct {

status pokemon.StatusService

statusTopic MessageBrokerTopic

combatTopic MessageBrokerTopic

}

func NewStatusWorker(

status pokemon.StatusService,

statusTopic MessageBrokerTopic,

combatTopic MessageBrokerTopic,

) StatusWorker {

return StatusWorker{

status: status,

statusTopic: statusTopic,

combatTopic: combatTopic,

}

}The Status worker

func (s *StatusWorker) Run(ctx context.Context) {

slog.Info("starting status worker")

for {

select {

case <-ctx.Done():

return

case event := <-s.statusTopic:

switch event.Type {

case PokemonEncountered:

slog.Info("paralyze pokemon", slog.Any("pokemon", event.Pokemon))

err := s.status.Paralyze(event.Pokemon)

if err != nil {

slog.Error("fail to paralyze pokemon", slog.Any("error", err))

continue

}

s.combatTopic <- Event{

Type: PokemonParalyzed,

Pokemon: event.Pokemon,

Trainer: event.Trainer,

}

}

}

}

}Other workers

We will re-use the same mechanism we used for status worker for other workers.

We will just check the solution, but take some time to work on it on your own if you need.

The Combat worker

Our second worker is the combat one!

File to open:

choreography/exercise2.mdThe Combat worker

type CombatWorker struct {

combat pokemon.CombatService

combatTopic MessageBrokerTopic

pokeballTopic MessageBrokerTopic

}

func NewCombatWorker(

combat pokemon.CombatService,

combatTopic MessageBrokerTopic,

pokeballTopic MessageBrokerTopic,

) CombatWorker {

return CombatWorker{

combat: combat,

combatTopic: combatTopic,

pokeballTopic: pokeballTopic,

}

}The Combat worker

func (c *CombatWorker) Run(ctx context.Context) {

slog.Info("starting combat worker")

for {

select {

case <-ctx.Done():

return

case event := <-c.combatTopic:

switch event.Type {

case PokemonParalyzed:

slog.Info("attack pokemon", slog.Any("pokemon", event.Pokemon))

err := c.combat.Attack(event.Pokemon)

if err != nil {

slog.Error("fail to attack pokemon", slog.Any("error", err))

continue

}

c.pokeballTopic <- Event{

Type: PokemonWeakened,

Pokemon: event.Pokemon,

Trainer: event.Trainer,

}

}

}

}

}The Pokéball worker

Last but not least, let's write the Pokéball worker!

File to open:

choreography/exercise3.mdThe Pokéball worker

type PokeballWorker struct {

pokeball pokemon.PokeballService

pokeballTopic MessageBrokerTopic

captureTopic MessageBrokerTopic

}

func NewPokeballWorker(

pokeball pokemon.PokeballService,

pokeballTopic MessageBrokerTopic,

captureTopic MessageBrokerTopic,

) PokeballWorker {

return PokeballWorker{

pokeball: pokeball,

pokeballTopic: pokeballTopic,

captureTopic: captureTopic,

}

}The Pokéball worker

func (p *PokeballWorker) Run(ctx context.Context) {

slog.Info("starting pokeball worker")

for {

select {

case <-ctx.Done():

return

case event := <-p.pokeballTopic:

switch event.Type {

case PokemonWeakened:

slog.Info("throw pokeball", slog.Any("pokemon", event.Pokemon))

err := p.pokeball.Throw(event.Trainer, event.Pokemon)

if err != nil {

slog.Error("fail to throw pokeball", slog.Any("error", err))

continue

}

slog.Info("pokemon captured", slog.Any("pokemon", event.Pokemon), slog.Any("trainer", event.Trainer))

p.catchTopic <- Event{

Type: PokemonCaptured,

Pokemon: event.Pokemon,

Trainer: event.Trainer,

}

}

}

}

}The main program

func main() {

combatTopic := make(choreography.MessageBrokerTopic, topicSize)

statusTopic := make(choreography.MessageBrokerTopic, topicSize)

pokeballTopic := make(choreography.MessageBrokerTopic, topicSize)

captureTopic := make(choreography.MessageBrokerTopic, topicSize)

combatService := pokemon.NewCombatService()

statusService := pokemon.NewStatusService()

pokeballService := pokemon.NewPokeballService()

statusWorker := choreography.NewStatusWorker(

statusService,

statusTopic,

combatTopic,

)

combatWorker := choreography.NewCombatWorker(

combatService,

combatTopic,

pokeballTopic,

)

pokeballWorker := choreography.NewPokeballWorker(

pokeballService,

pokeballTopic,

captureTopic,

)The main program

ctx, cancel := context.WithCancel(context.Background())

defer cancel()

for range workerPool {

go statusWorker.Run(ctx)

go combatWorker.Run(ctx)

go pokeballWorker.Run(ctx)

}

statusTopic <- choreography.Event{

Type: choreography.PokemonEncountered,

Pokemon: pokemon.Mewtwo(),

Trainer: pokemon.Sacha(),

}

reader := bufio.NewReader(os.Stdin)

fmt.Println("Waiting input to exit")

reader.ReadString('\n')

}Choreography

This is a simple preview of choreography. There's still a lot of work to do before using it on production:

- Use a real message broker and handle ack pattern

- Handle the errors properly

- Work on a rollback process of a workflow

- ...

Choreography: drawbacks

Choreography has some drawbacks:

- Difficulty in understanding the flow: the flow of the saga is distributed among services, making it challenging to have a centralized and clear definition of the entire saga’s progression

- Cyclic dependencies between services: Cyclic dependencies, where one service depends on another in a circular manner can introduce complexities and potential issues

- Risk of tight coupling: subscribing to all events that affect a service may lead to tight coupling, where services become highly dependent on each other’s internal implementation detail

Choreography: conclusion

Choreography can be a strong pattern when properly implemented. Go is a solid candidate for this kind of pattern, due to the easy implementation of concurrency.

I've never had the opportunity to use choreography "by the book" in production. But there's some concepts of choreography we can use to make our code more robust: using message brokers for communication between services, handling a global rollback mechanism, etc.

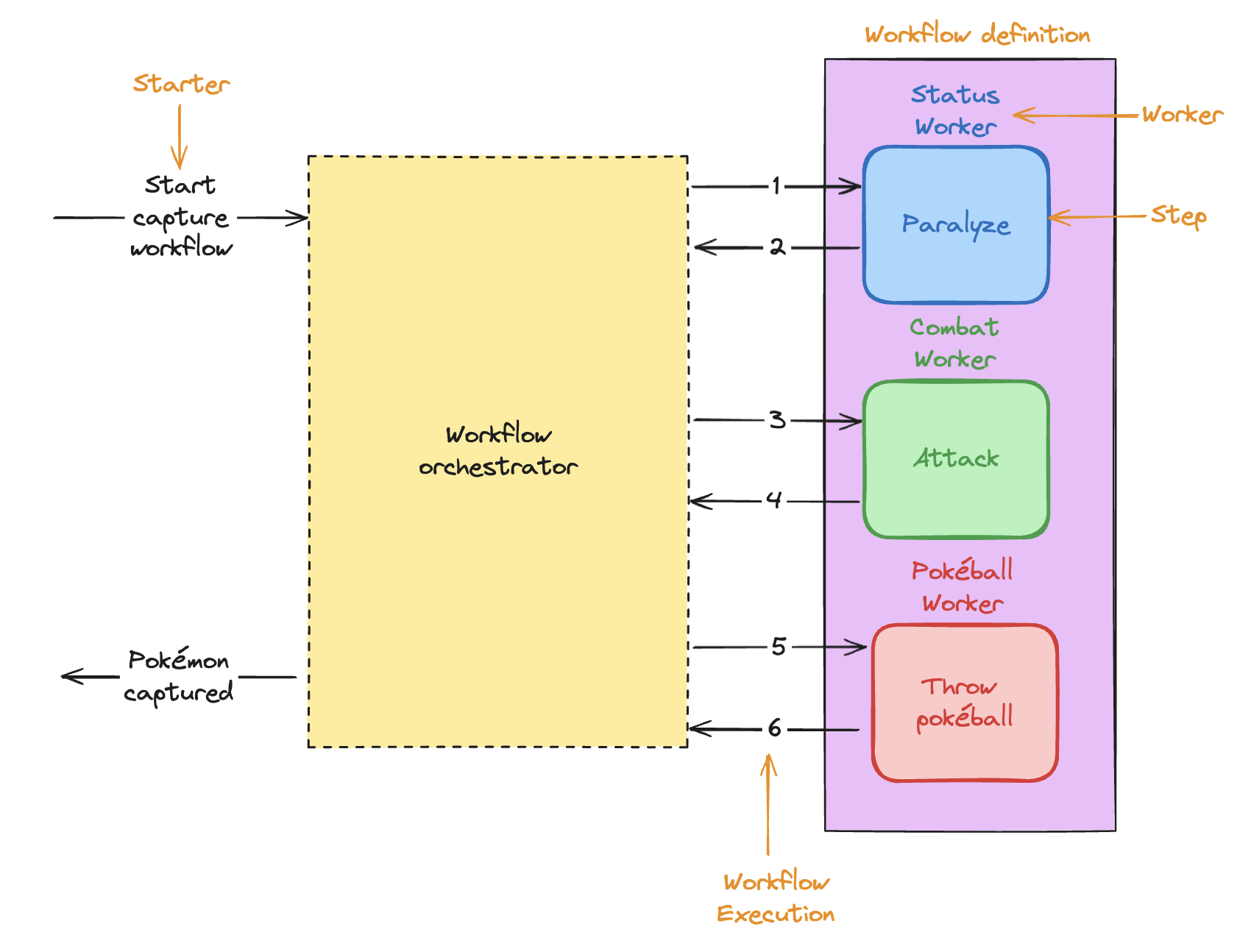

Orchestration

Introduction

Before starting to work on our orchestrator, there a couple of components I need to introduce from an orchestration point of view:

- Workflow definition: the definition of your workflow. It describe the sequence of steps that must be executed to execute your workflow.

- Step: a single unity of work, part of a workflow

- Workflow execution: an execution of your workflow definition

- Worker: the application in charge of executing the workflow and the steps

- Starter: the application in charge of starting a new workflow execution

Introduction

A new orchestrator

We will first write a generic orchestrator.

Then we will define a simple Helloworld workflow to test our orchestrator.

Finally we will write the Capture workflow!

Our orchestrator

Let's write a new orchestrator!

File to open:

orchestration/exercise1.mdOur orchestrator

type Orchestrator struct {

workflows WorkflowDefinitions

}

func NewOrchestrator() *Orchestrator {

return &Orchestrator{

workflows: make(WorkflowDefinitions, 0),

}

}

func (w *Orchestrator) Register(definer WorkflowDefiner) {

w.workflows = append(w.workflows, definer.Definition())

}Our orchestrator

func (w *Orchestrator) RunWorkflow(workflowExecution *WorkflowExecution) error {

workflowToExecute, err := w.workflows.FindByName(workflowExecution.WorkflowName)

if err != nil {

return err

}

slog.Info("executing workflow", slog.Any("workflow_definition", workflowToExecute), slog.Any("workflow_execution", workflowExecution))

for _, step := range workflowToExecute.Steps {

slog.Info("performing step", slog.Any("step", step), slog.Any("trainer", workflowExecution.Trainer), slog.Any("pokemon", workflowExecution.Pokemon))

err := step.Do(workflowExecution.Trainer, workflowExecution.Pokemon)

if err != nil {

return err

}

}

slog.Info("workflow executed", slog.Any("trainer", workflowExecution.Trainer), slog.Any("pokemon", workflowExecution.Pokemon))

return nil

}HelloWorld workflow

Let's now add a simple test workflow for your orchestrator.

File to open:

orchestration/exercise2.mdHelloWorld workflow

var (

HelloworldWorkflowName = "HelloWorld"

)

type HelloworldWorker struct{}

func (c *HelloworldWorker) helloTrainer(trainer *pokemon.Trainer, pokemon *pokemon.Pokemon) error {

fmt.Printf("Hello %s\n", trainer.Name)

return nil

}

func (c *HelloworldWorker) helloPokemon(trainer *pokemon.Trainer, pokemon *pokemon.Pokemon) error {

fmt.Printf("Hello %s\n", pokemon.Name)

return nil

}HelloWorld workflow

func (c *HelloworldWorker) Definition() *WorkflowDefinition {

return &WorkflowDefinition{

Name: HelloworldWorkflowName,

Steps: []*Step{

{

Name: "Hello Trainer",

Do: c.helloTrainer,

},

{

Name: "Hello Pokémon",

Do: c.helloPokemon,

},

},

}

}Bonus: already performed steps

func (w *Orchestrator) RunWorkflow(workflowExecution *WorkflowExecution) error {

workflowToExecute, err := w.workflows.FindByName(workflowExecution.WorkflowName)

if err != nil {

return err

}

alreadyPerformedSteps := workflowExecution.PerformedSteps

for _, step := range workflowToExecute.Steps {

if len(alreadyPerformedSteps) > 0 && alreadyPerformedSteps[0] == step.Name {

alreadyPerformedSteps = alreadyPerformedSteps[1:]

continue

}

err := step.Do(workflowExecution.Trainer, workflowExecution.Pokemon)

if err != nil {

return err

}

workflowExecution.PerformedSteps = append(workflowExecution.PerformedSteps, step.Name)

}

return nil

}Capture Mewtwo

Now that our orchestrator is built, it's easy to rewrite our capture workflow with it.

Capture workflow

Let's capture Mewtwo!

File to open:

orchestration/exercise3.mdCapture workflow

var (

CapturePokemonWorkflowName = "CapturePokemon"

)

type CapturePokemonWorker struct {

status pokemon.StatusService

combat pokemon.CombatService

pokeball pokemon.PokeballService

}

func NewCapturePokemonWorker(

status pokemon.StatusService,

combat pokemon.CombatService,

pokeball pokemon.PokeballService,

) *CapturePokemonWorker {

return &CapturePokemonWorker{

status: status,

combat: combat,

pokeball: pokeball,

}

}Capture workflow

func (c *CapturePokemonWorker) attack(trainer *pokemon.Trainer, pokemon *pokemon.Pokemon) error {

return c.combat.Attack(pokemon)

}

func (c *CapturePokemonWorker) paralyze(trainer *pokemon.Trainer, pokemon *pokemon.Pokemon) error {

return c.status.Paralyze(pokemon)

}

func (c *CapturePokemonWorker) throwPokeball(trainer *pokemon.Trainer, pokemon *pokemon.Pokemon) error {

return c.pokeball.Throw(trainer, pokemon)

}Capture workflow

var (

CapturePokemonWorkflowName = "CapturePokemon"

)

func (c *CapturePokemonWorker) Definition() *WorkflowDefinition {

return &WorkflowDefinition{

Name: CapturePokemonWorkflowName,

Steps: []*Step{

{

Name: "Paralyze",

Do: c.paralyze,

},

{

Name: "Attack",

Do: c.attack,

},

{

Name: "ThrowPokeball",

Do: c.throwPokeball,

},

},

}

}Bonus: Capture workflow

func NewCapturePokemonWorkflowExecution(trainer *pokemon.Trainer, pokemon *pokemon.Pokemon) *WorkflowExecution {

return &WorkflowExecution{

ID: uuid.New().String(),

WorkflowName: CapturePokemonWorkflowName,

PerformedSteps: []string{},

Trainer: trainer,

Pokemon: pokemon,

}

}The main program

func main() {

orchestrator := orchestration.NewOrchestrator()

combatService := pokemon.NewCombatService()

statusService := pokemon.NewStatusService()

pokeballService := pokemon.NewPokeballService()

orchestrator.Register(orchestration.NewCapturePokemonWorker(

statusService,

combatService,

pokeballService,

))

workflowExecution := orchestration.NewCapturePokemonWorkflowExecution(pokemon.Sacha(), pokemon.Mewtwo())

err := orchestrator.RunWorkflow(workflowExecution)

if err != nil {

slog.Error("fail to run workflow", slog.Any("error", err))

}

}Orchestration

We took some time to start writing our first orchestrator! Well done.

But there's still a lot of missing features before being ready for production:

- Error management and retries

- Saving the lifecycle of a workflow execution

- After each step performed

- At the end of the workflow

- Handling step's outputs

- And many other features you might need: workflow priority, hooks before and after a step, concurrent runs of workflows, lock resources, etc.

Orchestration

Writing an orchestrator is a huge work. It's quite easy to have a working POC (juste like we did), but it requires much more work to have something resilient, robust, with many features you might need.

Would you consider writing your own database system if you succeed to write a small application that writes data to a file?

It's quite the same for workflow orchestration. Be careful about loosing focus on your business!

Orchestration

Writing an orchestrator is a good exercise to understand a lot of features in Go or other languages. But it's probably not your core business to write a production-ready orchestrator!

The good news is that there's a lot of existing open-source orchestrators we can use with Go.

Orchestration engines

Orchestration engines

There's a lot of existing orchestration engines. Each of them has its strengths and weaknesses!

You can find a (non-exhaustive) list here: https://github.com/meirwah/awesome-workflow-engines

I like to classify orchestrators in two types:

- As-file

- As-code

As-file orchestrators

As-file orchestrators are orchestrators where your workflow is defined in plain-text files, JSON, YAML or other "non-code" format.

Each step of the workflow uses a dedicated engine to do their work: HTTP engine, SSH engine, GRPC engine, etc.

Engines will then sometimes call your code to execute a step.

For example, the HTTP engine will perform an HTTP code to your API.

As-file orchestrators: uTask

uTask, written by OVHcloud, is a good example of "as-file orchestrator".

Your workflow definition is defined in a YAML file, handling a lot of the workflow intelligence: retry policy, error management, etc.

uTask

steps:

getTime:

description: Get UTC time

retry_pattern: minutes

action:

type: http

configuration:

url: http://worldclockapi.com/api/json/utc/now

method: GET

sayHello:

description: Echo a greeting in your language of choice

dependencies: [getTime]

action:

type: echo

configuration:

output:

message: {{.step.getTime.output.currentDateTime}As-file orchestrators: Camunda

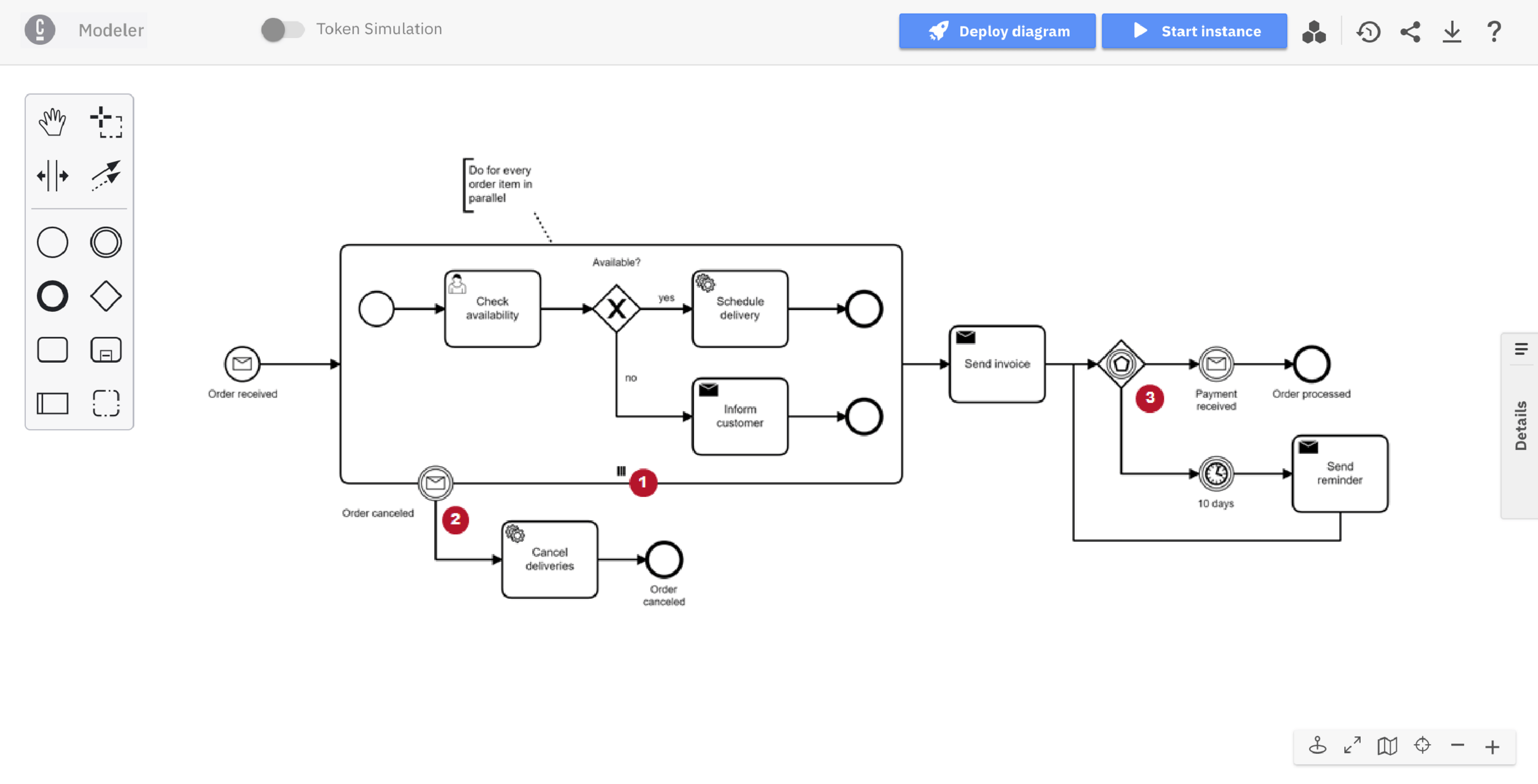

Camunda is going a step further: your workflows are defined in a standard format, BPMN (Business Process Model and Notation), and there's a graphic tool to create your workflow.

It allows non-tech people (like product owner) writing the business process, as they usually hold the business knowledge.

You will then write an external task worker with Camunda SDK to execute your business code.

Camunda modeler

Conductor

Created at Netflix, Conductor is now independent.

In Conductor, you write your workflows with a JSON file (can be created with graphic tool).

The orchestrator will then run your workflows.

Conductor

{

"name": "first_sample_workflow",

"description": "First Sample Workflow",

"version": 1,

"tasks": [

{

"name": "get_population_data",

"taskReferenceName": "get_population_data",

"inputParameters": {

"http_request": {

"uri": "https://datausa.io/api/data?drilldowns=Nation&measures=Population",

"method": "GET"

}

},

"type": "HTTP"

}

],

"inputParameters": [],

"outputParameters": {

"data": "${get_population_data.output.response.body.data}",

"source": "${get_population_data.output.response.body.source}"

},

"schemaVersion": 2,

"restartable": true,

"workflowStatusListenerEnabled": false,

"ownerEmail": "example@email.com",

"timeoutPolicy": "ALERT_ONLY",

"timeoutSeconds": 0

}And other ones

You will easily find other "as-file" orchestrators:

- Mistral

- CDS

- etc.

As-code orchestrators

As-code orchestrators work with a different mindset: your workflows are defined in your code, with your language, using a provided SDK.

Your code then maintain the business logic.

As-code orchestrators

For some languages, there's a lot of options, like for Python:

- Airflow

- Celery

- Prefect

- etc.

As-code orchestrators

In Go, we don't have that luxury.

I personally like those ones:

- Temporal: https://temporal.io/

- Durable Task: https://github.com/microsoft/durabletask-go

Temporal

func Workflow(ctx workflow.Context, name string) (string, error) {

ao := workflow.ActivityOptions{

StartToCloseTimeout: 10 * time.Second,

}

ctx = workflow.WithActivityOptions(ctx, ao)

logger := workflow.GetLogger(ctx)

logger.Info("HelloWorld workflow started", "name", name)

var result string

err := workflow.ExecuteActivity(ctx, Activity, name).Get(ctx, &result)

if err != nil {

logger.Error("Activity failed.", "Error", err)

return "", err

}

logger.Info("HelloWorld workflow completed.", "result", result)

return result, nil

}

func Activity(ctx context.Context, name string) (string, error) {

logger := activity.GetLogger(ctx)

logger.Info("Activity", "name", name)

return "Hello " + name + "!", nil

}As-code or as-file?

There's not a perfect answer to this question. Both are working fine.

One of the main issue with the "as-file" approach is that your business rules are split between your code and your workflow definition file.

And to be more flexible, as-file orchestrators often implements "code logic" like loops, conditional statements, error management, making the workflow a bit difficult to read. If I want to write an algorithm, I really prefer to write it in Go with unit tests etc. than in pseudo-code in YAML.

Example: https://github.com/ovh/utask/tree/master?tab=readme-ov-file#step-foreach

As-code or as-file?

Choosing the workflow orchestrator will change the shape of your project, so it's important to take time to challenge and understand how they are working.

As we are in a Go workshop, I find more appropriate to continue the workshop by using as-code orchestrators.

That's why it's time to meet Temporal!

Temporal

Temporal

Temporal is "Durable execution platform" (aka a workflow orchestration engine).

Born in Uber (previously named Cadence), Temporal is now an independent product.

First release in 2020.

Temporal

Opensource, MIT-licensed.

Business model with a cloud offer on AWS.

Many big users and contributors: Stripe, Datadog, Hashicorp, TF1, and OVHcloud!

Temporal core concepts

Temporal has 5 core concepts:

- Workflow: define how your activities must be sequenced

- Activity: call to dependencies, code that might fail

- Retry policy: define how your workflows and activities will retry

- Worker: execute your code

- Starter: ask Temporal to start a new workflow execution

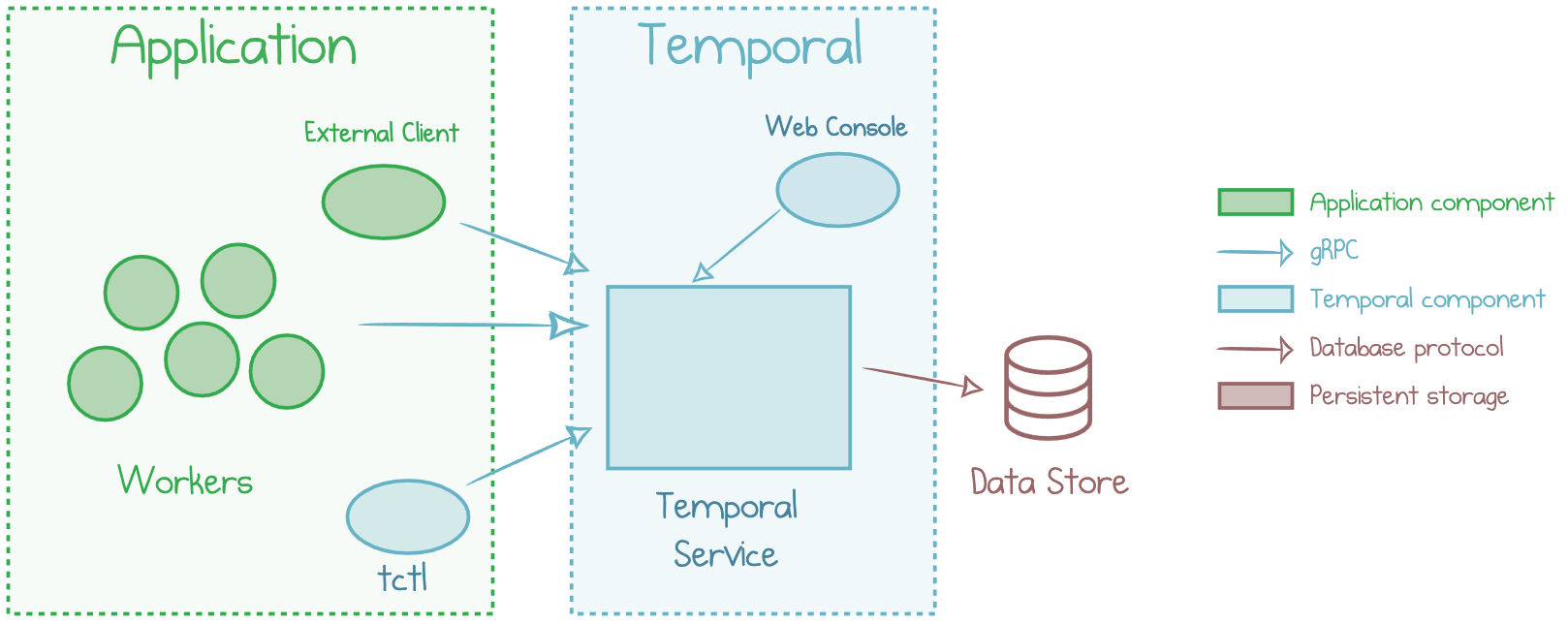

Simple architecture

Deployment

Temporal can be easily deployed in a development environment with a single CLI and no other dependencies (we will use this).

In production, it runs over Kubernetes, with data store like PostgreSQL, Cassandra or MySQL.

Install Temporal

Let's start a development server for Temporal.

File to open:

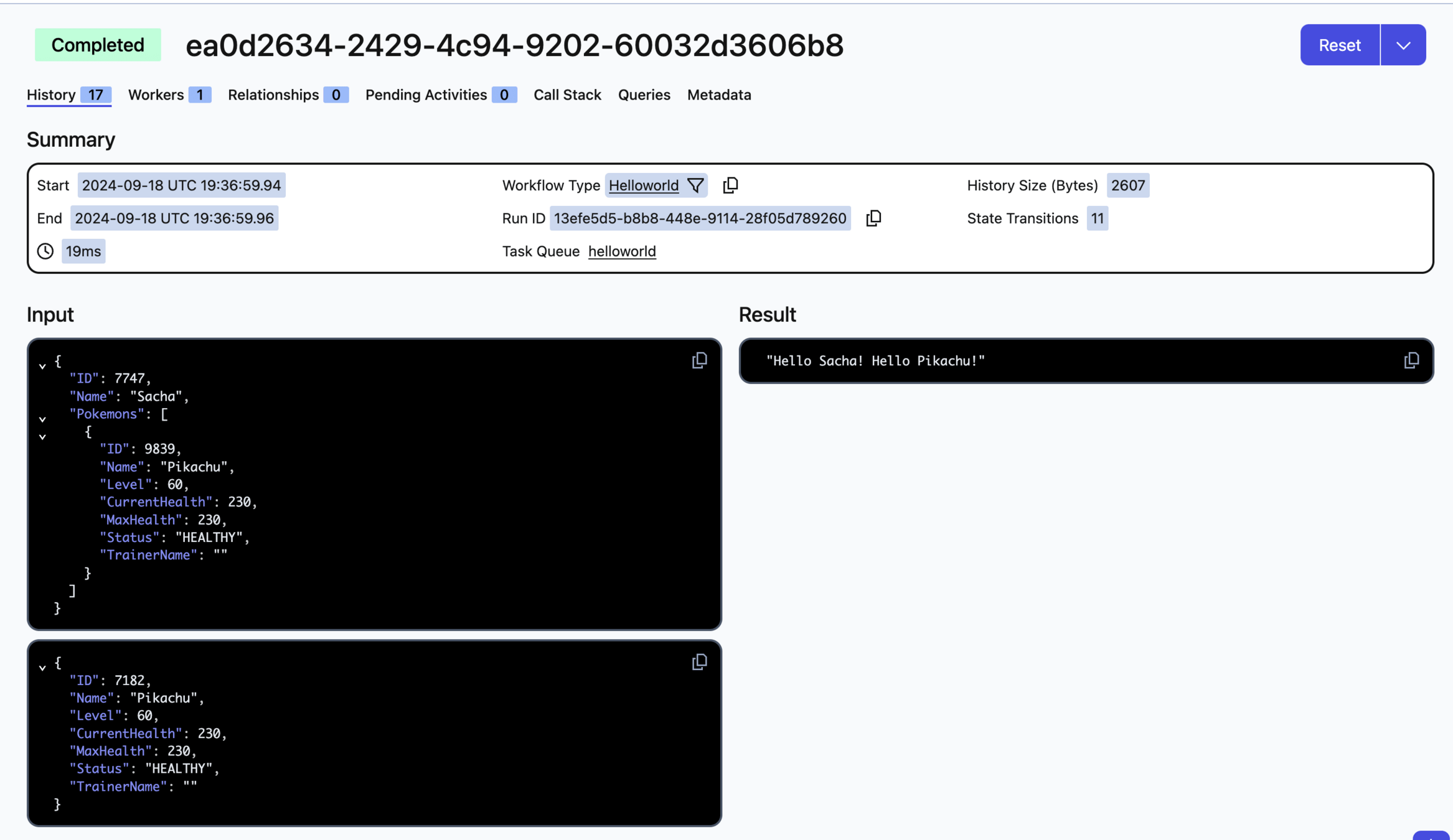

temporal/exercise0.mdHelloworld workflow

We will write a simple workflow in Temporal!

File to open:

temporal/helloworld/exercise1.mdHelloworld workflow

func SayHelloToTrainer(ctx context.Context, trainer *pokemon.Trainer) (string, error) {

logger := activity.GetLogger(ctx)

logger.Info("SayHelloToTrainer", "name", trainer.Name)

return fmt.Sprintf("Hello %s!", trainer.Name), nil

}

func SayHelloToPokemon(ctx context.Context, pokemon *pokemon.Pokemon) (string, error) {

logger := activity.GetLogger(ctx)

logger.Info("SayHelloToPokemon", "name", pokemon.Name)

return fmt.Sprintf("Hello %s!", pokemon.Name), nil

}Helloworld workflow

func Helloworld(ctx workflow.Context, trainer *pokemon.Trainer, pokemon *pokemon.Pokemon) (string, error) {

ao := workflow.ActivityOptions{StartToCloseTimeout: 10 * time.Second}

ctx = workflow.WithActivityOptions(ctx, ao)

logger := workflow.GetLogger(ctx)

var result, finalResult string

err := workflow.ExecuteActivity(ctx, SayHelloToTrainer, trainer).Get(ctx, &result)

if err != nil {

logger.Error("Activity failed.", "Error", err)

return "", err

}

finalResult += result

err = workflow.ExecuteActivity(ctx, SayHelloToPokemon, pokemon).Get(ctx, &result)

if err != nil {

logger.Error("Activity failed.", "Error", err)

return "", err

}

finalResult += " " + result

return finalResult, nil

}Activity options are a way to properly customize how your activities will run, how errors will be handled, how retry should work.

retrypolicy := &temporal.RetryPolicy{

InitialInterval: time.Second,

BackoffCoefficient: 2.0,

MaximumInterval: time.Second * 100, // 100 * InitialInterval

MaximumAttempts: 0, // Unlimited

NonRetryableErrorTypes: []string, // empty

}Worker

func main() {

c, err := client.Dial(client.Options{

HostPort: "localhost:7233",

Logger: log.NewStructuredLogger(slog.Default()),

})

if err != nil {

slog.Error("unable to create client", slog.Any("error", err))

return

}

defer c.Close()

w := worker.New(c, "helloworld", worker.Options{})

w.RegisterWorkflow(helloworld.Helloworld)

w.RegisterActivity(helloworld.SayHelloToTrainer)

w.RegisterActivity(helloworld.SayHelloToPokemon)

err = w.Run(worker.InterruptCh())

if err != nil {

slog.Error("unable to start worker", slog.Any("error", err))

return

}

}Starter

func main() {

c, err := client.Dial(client.Options{

HostPort: "localhost:7233",

Logger: log.NewStructuredLogger(slog.Default()),

})

defer c.Close()

workflowOptions := client.StartWorkflowOptions{

ID: uuid.New().String(),

TaskQueue: "helloworld",

}

we, err := c.ExecuteWorkflow(context.Background(), workflowOptions, helloworld.Helloworld, pokemon.Sacha(), pokemon.Pikachu())

var result string

err = we.Get(context.Background(), &result)

slog.Info("workflow result", slog.Any("result", result))

}UI

How Temporal is working?

Based on an execution tree and (lots of) events.

Can restart a workflow from the point of failure.

To do so, there a important rule to understand: workflow determinism.

Workflow determinism

Your workflow definition (ie. code for the workflow, not the activities) must be deterministic.

This means a workflow must always do the same thing, given the same inputs. It allows replays of a workflow.

There's two main reasons for a workflow to behave differently with the same inputs:

- Code changes: use versioning

- Using random or time functions: use the built-in Temporal functions

Capture workflow

Time to capture Mewtwo. Again.

File to open:

temporal/capture/exercise1.mdCapture workflow

func (w *Worker) ParalyzeActivity(ctx context.Context, pokemon *pokemon.Pokemon) (*pokemon.Pokemon, error) {

return pokemon, w.status.Paralyze(pokemon)

}

func (w *Worker) AttackActivity(ctx context.Context, pokemon *pokemon.Pokemon) (*pokemon.Pokemon, error) {

return pokemon, w.combat.Attack(pokemon)

}

type ThrowPokeballOutput struct {

Pokemon *pokemon.Pokemon

Trainer *pokemon.Trainer

}

func (w *Worker) ThrowPokeballActivity(ctx context.Context, trainer *pokemon.Trainer, pokemon *pokemon.Pokemon) (ThrowPokeballOutput, error) {

return ThrowPokeballOutput{Pokemon: pokemon, Trainer: trainer}, w.pokeball.Throw(trainer, pokemon)

}Capture workflow

func (w *Worker) CapturePokemonWorkflow(ctx workflow.Context, trainer *pokemon.Trainer, pokemon *pokemon.Pokemon) (*CapturePokemonOutput, error) {

ao := workflow.ActivityOptions{

StartToCloseTimeout: 10 * time.Second,

}

ctx = workflow.WithActivityOptions(ctx, ao)

logger := workflow.GetLogger(ctx)

logger.Info("CapturePokemon workflow started")

err := workflow.ExecuteActivity(ctx, w.ParalyzeActivity, pokemon).Get(ctx, pokemon)

err = workflow.ExecuteActivity(ctx, w.AttackActivity, pokemon).Get(ctx, pokemon)

var throwPokeballOutput ThrowPokeballOutput

err = workflow.ExecuteActivity(ctx, w.ThrowPokeballActivity, trainer, pokemon).Get(ctx, &throwPokeballOutput)

logger.Info("CapturePokemon workflow completed.")

return &CapturePokemonOutput{

Trainer: throwPokeballOutput.Trainer,

Pokemon: throwPokeballOutput.Pokemon,

}, nil

}Error management

Let's have a look on how Temporal is handling errors.

File to open:

temporal/helloworld/exercise2.mdError management

func SayHelloToProfessorOak(ctx context.Context) (string, error) {

resp, err := http.Get("localhost:8080/hello")

if err != nil {

return "", err

}

defer resp.Body.Close()

result, err := io.ReadAll(resp.Body)

if err != nil {

return "", err

}

return string(result), nil

}Going further

We implemented a couple of simple workflows with Temporal, but we didn't play at all with all its features!

For example, you can play with:

- Error management: try to return an error in one of your activity, restart your worker, and check how Temporal is handling retries, play with retry policy parameters, etc.

- Splitting your workload with multiple workers: try to create different workers, one for managing only the ParalyzeActivity, another one for the AttackActivity, etc.

- Play with Query and Signals to wait for human interactions with your workflow

- etc.

Conclusion

Conclusion

I strongly recommend to spend time in using and understanding existing orchestrators instead of writing your own.

At OVHcloud, you will find mainly those orchestrators:

- uTask

- Camunda

- Temporal

- Mistral

CIO is working on managed Temporal!

What's next?

- Temporal 101: https://learn.temporal.io/courses/temporal_101/go/

- Temporal features: https://docs.temporal.io/evaluate/development-production-features/

- Temporal Go samples: https://github.com/temporalio/samples-go

- Some talks in French (by OVH employees!):

- Gwendal Leclerc: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dRWbLbewUzM

- Alexandre Vilain: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jIncBsYiZ3E

- Nathan Castelein: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2SYlMsQiXpQ

Thanks! Questions?