Effective Learning

Ninnat Dangniam

QIS Group Meeting

28 November 2023

* I'm not an expert in learning, neuroscience, or psychology, so take these information with a heap of salt

Bibliography

- Barbara Oakley and Terry Sejnowski

- Benjamin Keep

- Science of Learning Concepts for Teachers (Project Illuminated), Marc Beardsley

Retrieval: Active recall

Domain-specific practice

Benjamin Keep, When Active Learning Goes Right (And Wrong)

Organized Structure

Isolated facts or concepts are rarely useful

- How it is used (checklist? synthesis?)

- How they are related

- How many ways they can be related

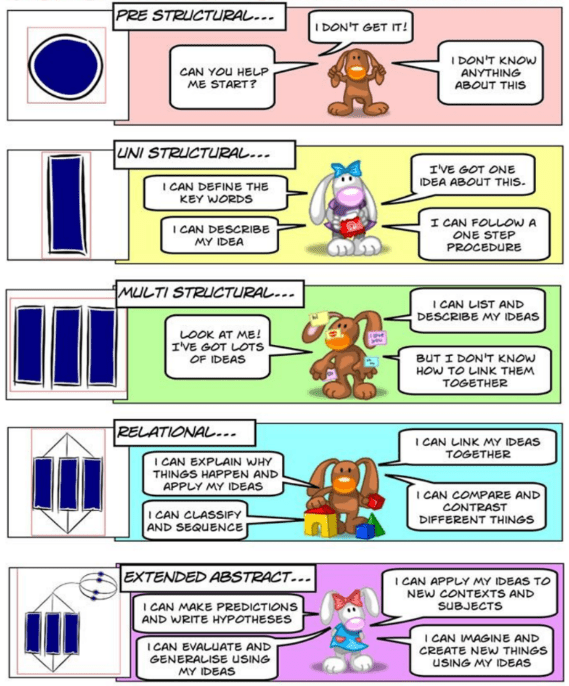

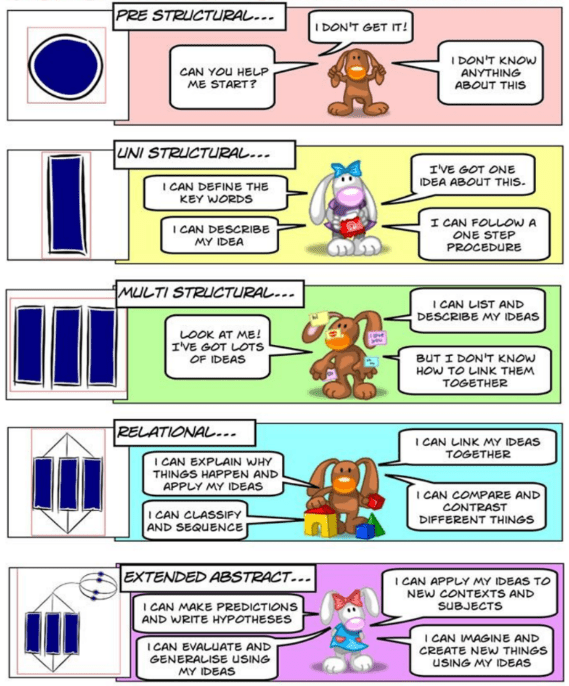

SOLO taxonomy (Biggs & Collis 1982)

Textbooks and lectures necessarily present information in a linear, and often logical order

Src: Wikipedia

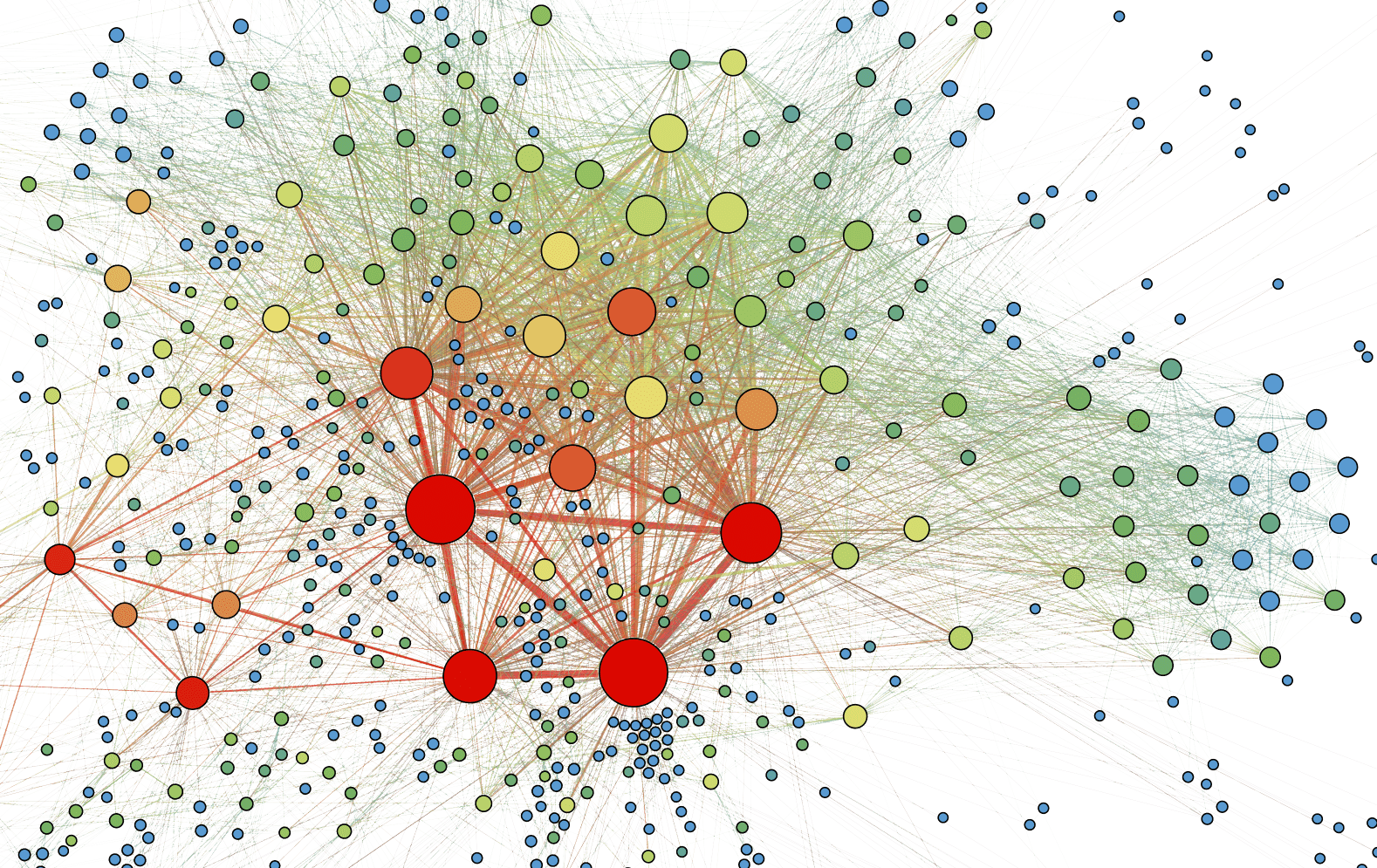

Real information are intricately interconnected, with certain pieces of information being more important than others, whether because they are hubs, or they are used frequently.

Organized Structure

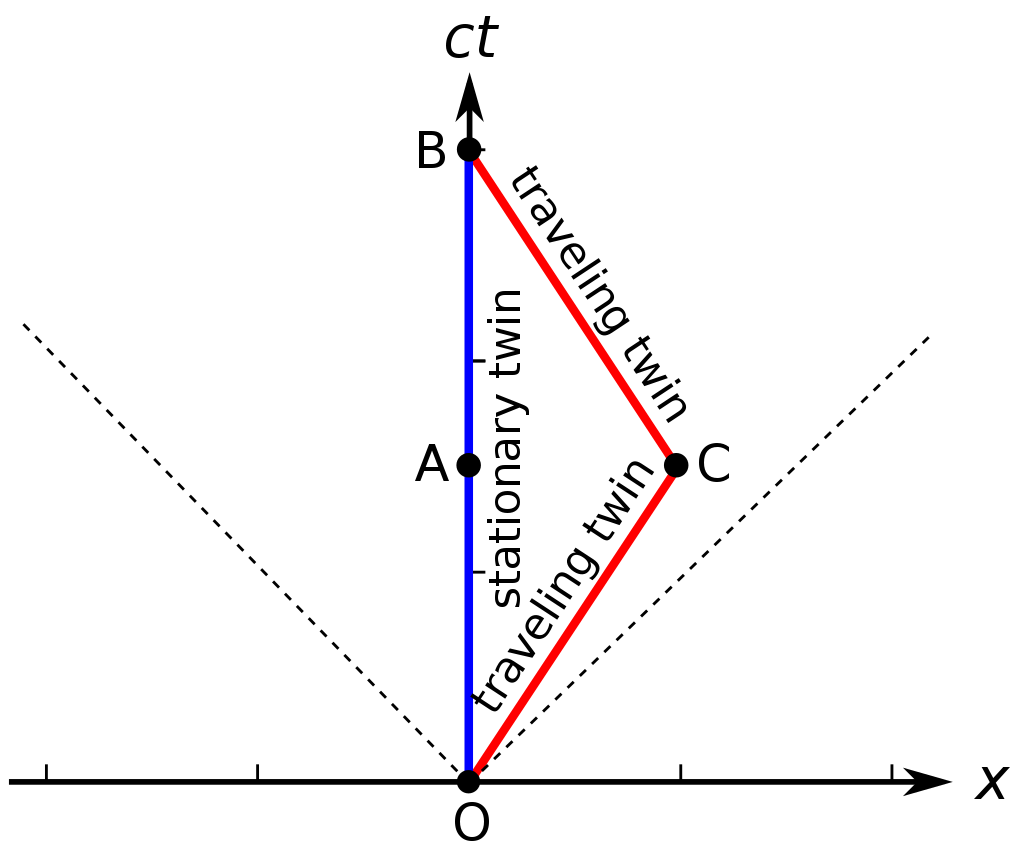

SR is a theory of the invariant interval

\(\textrm{d}s^2 = c^2 \textrm{d}t^2 - \textrm{d}x^2\)

SR can be derived from two postulates:

- The law of physics are the same in every inertial frame of reference

- The speed of light is a constant

Logical, but not immediately useable

Src: Wikipedia

Organized Structure

Organized Structure

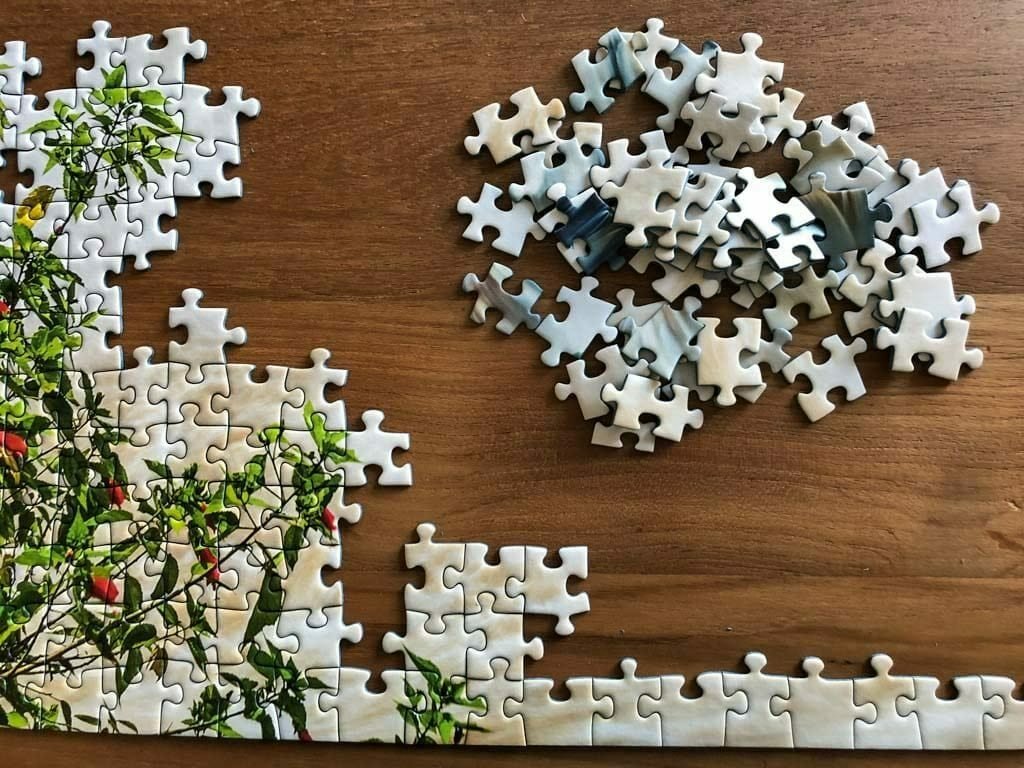

Without an existing scaffold, you won't be able to judge whether or how a new piece of information fits into a big picture. You need an existing structure to evaluate new information (correctness, importance etc.)

Src: Jigsaw Puzzle Queen

A structure is needed even before you attempt to study anything in details.

- A moderate amount of confusion is necessary

- Priming AKA Pre-studying

- Skimming scientific papers

Learning and Memory

Two big problems with working memory

- Memory decay \(\implies\) Encoding via active recall

- Limited capacity \(\implies\) Chunking

Sensory register

Short-term memory

Long-term memory

Attention

Encoding

Retrieval

Rehearsal

(Working memory)

Forgotten

Forgotten

- 10-15 s

- 4 chunks

- minutes to lifetime

Science of Learning Concepts for Teachers (Project Illuminated), Marc Beardsley

Learning and Memory

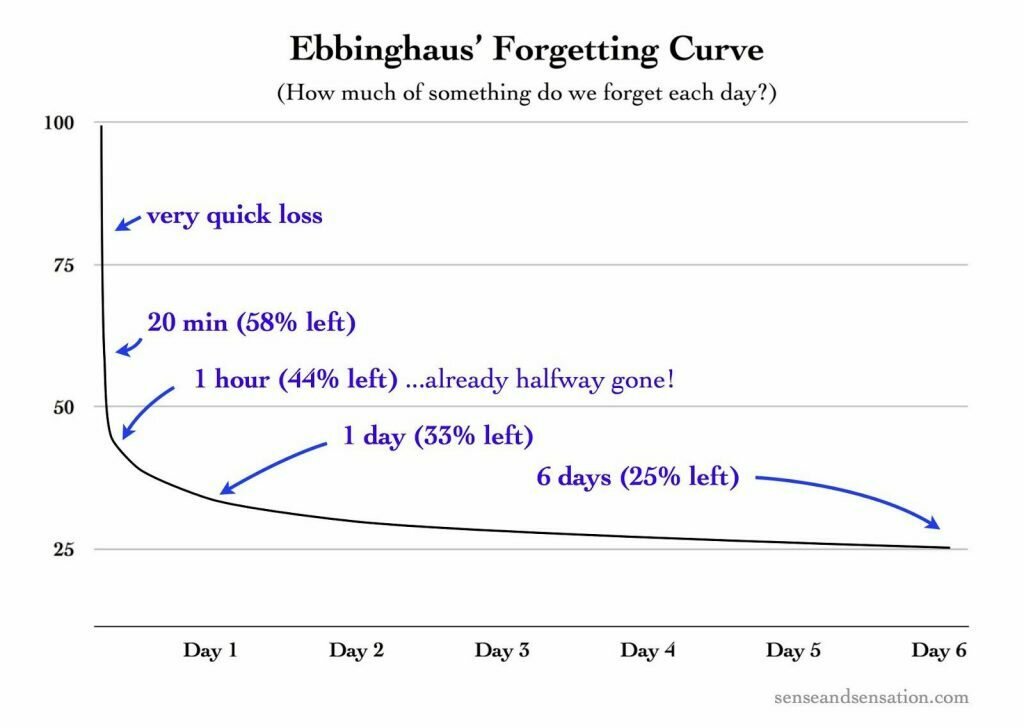

This is why cramming is bad in the long term

Learning and Memory

Src: Wikipedia

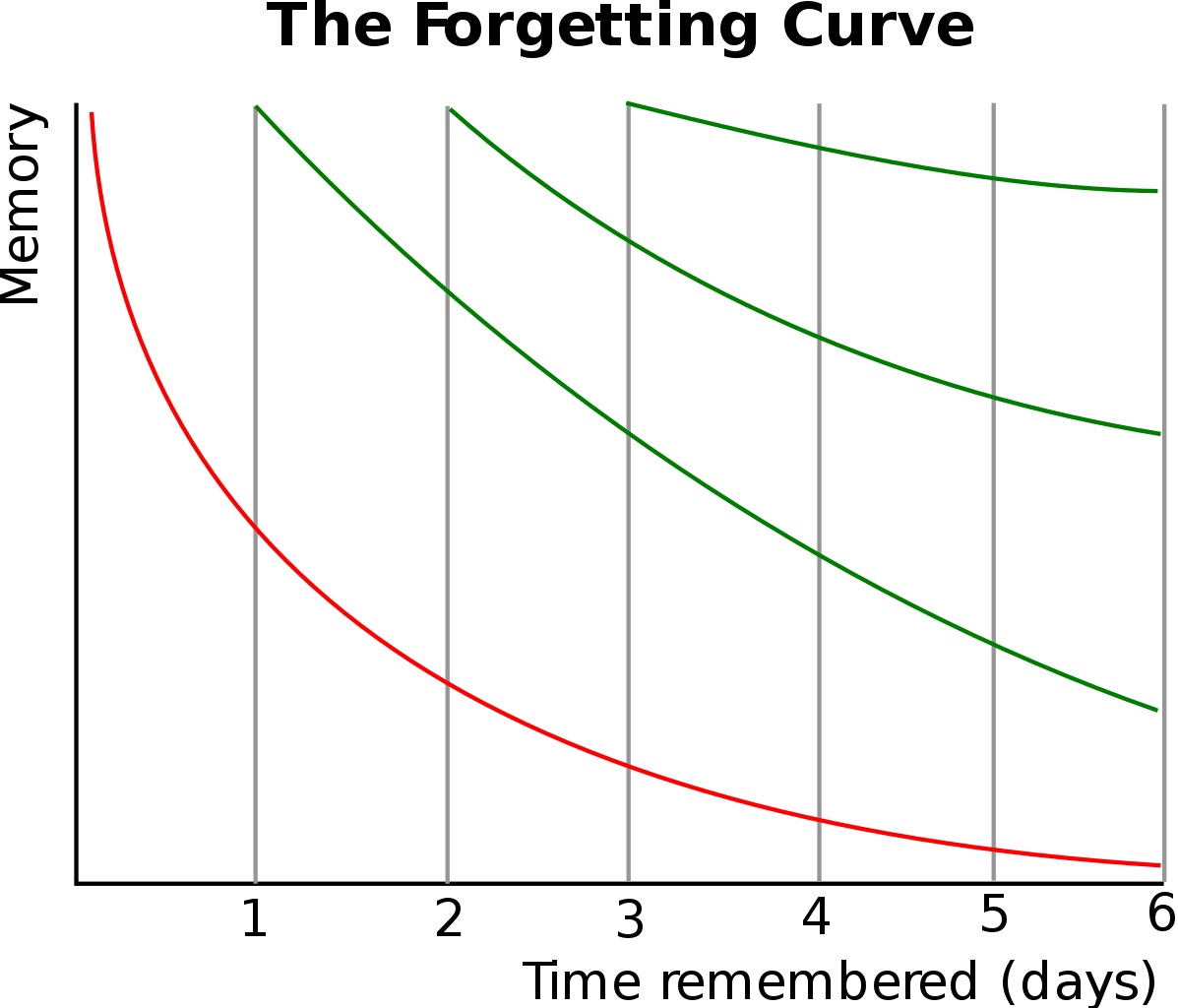

Spaced repetition is an extremely well established method to combat memory decay

Simple principle:

information that is rarely retrieved is discarded

Aiding tools like flashcards and Anki exist, but using them effectively can be time-consuming and requires a level of expertise on its own.

Intriguingly, Michael Nielsen has extensively been experimenting with the system and even co-authored Quantum Country, an interactive lesson on quantum computing based on the idea of spaced repetition.

Active Recall

Rather than reviewing notes as is, it is much better to simply recall information

For example, try writing down what you learned as much as possible without looking at your notes, then check your notes to see what you have missed.

(This is akin to testing yourself)

Feynman technique: teach a topic you want to learn to others. You will realize gaps in your knowledge very quickly.

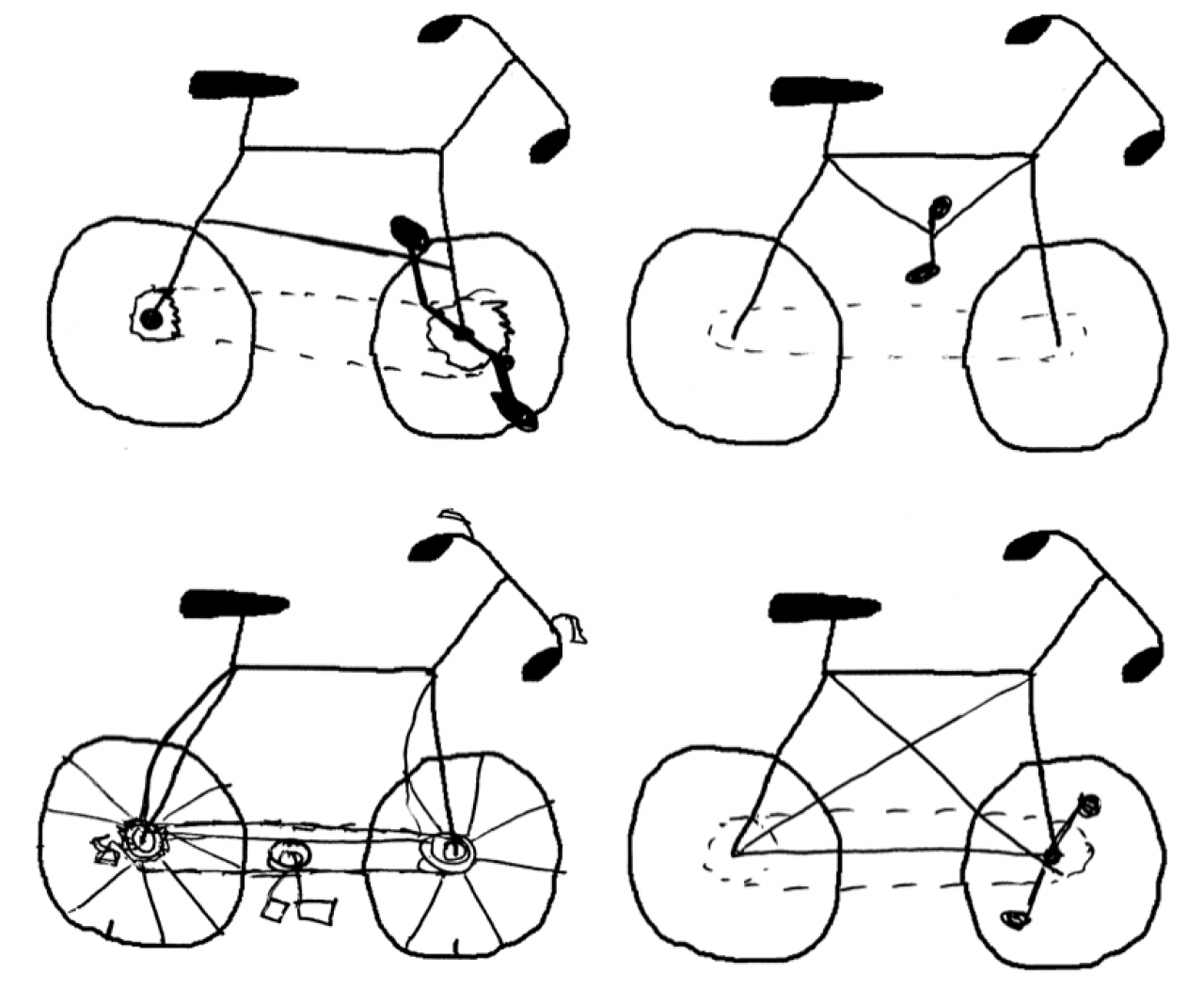

Recall \(\neq\) Recognize!

Recognition is a much easier form of retrieval, but at a much "lower resolution"

Src: Dave Atkinson

- Writing notes verbatim is not useful*, as the information has not been processed in your brain; learning occurs in the brain, not on paper

- Same for re-reading notes

- Delayed note-taking is active recall

- This is also why you shouldn't be too quick to look at solutions when you got stuck

*You might be worried, of course, that without taking notes you might not remember anything from the lecture. This is where priming and taking minimal notes during lectures is recommended.

Chunking and Intuition

Chunking bypasses the limit of working memory, and is related to a hallmark of mastery

Chess experts don't memorize the position of each individual piece on the board. Indeed, they can't; an upper bound for the number of valid chess positions is probably around \(10^{46}\) [2].

Instead, it is believed that chess players become experts by forming and accessing complex chunks in long-term memory [3].

[1]: The cognitive cost of expertise, WIRED

[2]: Fun fact: an upper bound to the number of chess games, the Shannon number, is about \(10^{120}\).

Chunking and Intuition

Processes of using chunks are

- Novices: deliberate, mechanical, difficult

- Experts: unconscious, effortless, becoming the flow state

"[Experts] have learned to perceive the world in a useful way." [1]

A chess grandmaster, described the process as trying to make sense of the chess positions. "Meaningful" chunks (patterns) are easier to remember than random ones.

Chunking and Intuition

Pre-rigorous

Rigorous

Post-rigorous

There's more to mathematics than rigour and proofs, Terence Tao

The transition from the first stage to the second is well known to be rather traumatic, with the dreaded “proof-type questions” being the bane of many a maths undergraduate. [...] But the transition from the second to the third is equally important, and should not be forgotten.

Unlearn

bad intuition

Learn

Good intuition

- Read textbooks, research papers, and solve problems; these domain-specific experiences are still necessary

- But effective learning requires more:

- Information needs to be organized for coherent understanding and efficient retrieval

- Practice active recall regularly (and/or teach the topic you want to learn to others or write your own textbook)

- Be aware when your learning method is ineffective (e.g. rote memorization, taking or re-reading notes without mentally engaging with the materials)

- Let's do skimming right now!

Summary

A 2014 MOOC by Barbara Oakley, a signal officer-turned-Professor of Engineering, and Terry Sejnowski, a neuroscientist

- Focused vs Diffuse mode [09:00]

- Procrastination - Pomodoro technique [17:30]

- Sleep and exercise [22:30]

- Memory and retention, spaced repetition [29:18]

- Chunking [33:42-38:30]

- Active recall, Feynman method [46:44-49:30]

- Poor memory, imposter syndrome, illusion of understanding etc.

These taxonomies alone don't answer how one can achieve mastery

Organizing knowledge

Isolated facts or concepts are rarely useful

- How it is used (checklist? synthesis?)

- How they are related

- How many ways they can be related

SOLO taxonomy (Biggs & Collis 1982)

Active recall should work on all levels, not just memorization of facts or concepts

- Novices: Deliberate, mechanical, difficult

- Experts: Unconscious, effortless, being in the flow state

Chess experts don't memorize the position of each individual piece on the board. Indeed, they can't; an upper bound for the number of valid chess positions is probably around \(10^{46}\) [2].

Instead, it is believed that chess players become experts by forming and accessing complex chunks in long-term memory [3].

[1]: The cognitive cost of expertise, WIRED

[2]: Fun fact: an upper bound to the number of chess games, the Shannon number, is about \(10^{120}\).

"[Experts] have learned to perceive the world in a useful way." [1]

What is Mastery?

What is Mastery?

Unlearn

bad intuition

Pre-rigorous

Rigorous

Post-rigorous

Learn

Good intuition

Rigor, devourer of misguidance, harbinger of true insight

- "The point of rigour is not to destroy all intuition; instead, it should be used to destroy bad intuition while clarifying and elevating good intuition."

- "an overly literal mindset can lead to “compilation errors” when one encounters even a single typo or ambiguity in such a paper."