Modeling the Past

The Jesuit Plantation Project as a Case Study in Data-Driven History

Sharon M. Leon

University of Missouri-St. Louis, Center for Humanities

March 10, 2021

@sharonmleon

How Shall We Represent Their Lives?

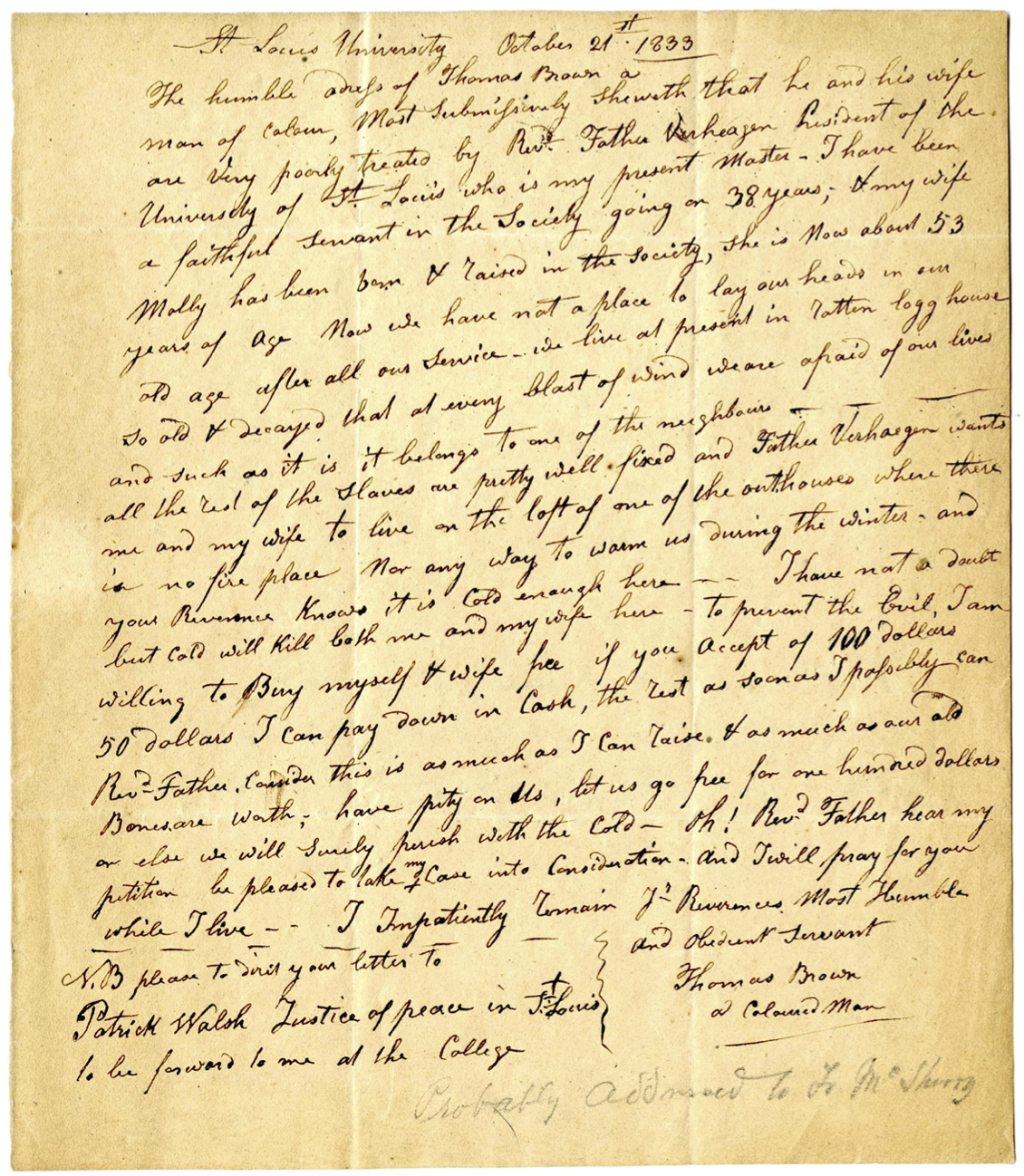

Thomas Brown, 1833

"Now we have not a place to lay our heads in our old age after all our Service. We live at present in rotten logg house so old & decayed that at every blast of wind we are afraid of our lives and such as it is it belongs to one of the neighbors. - - - all the rest of the Slaves are pretty well fixed and Father Verheagen wants me and my wife to live in the loft of one of the outhouses where there is no fire place Nor any way to warm us during the winter - and your Reverence Knows it is Cold enough here. I have not a doubt but cold will Kill both me and my wife here."

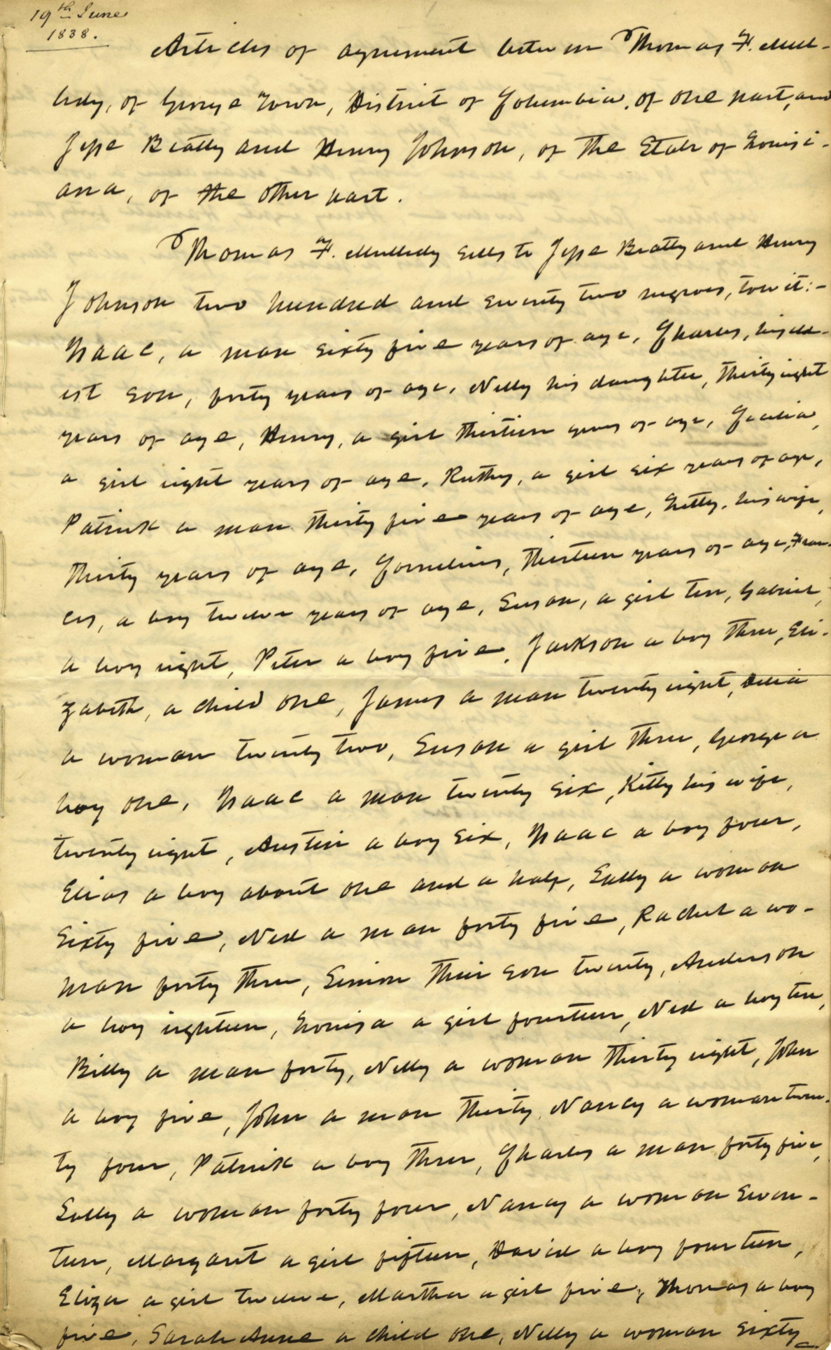

The 1838 Sale

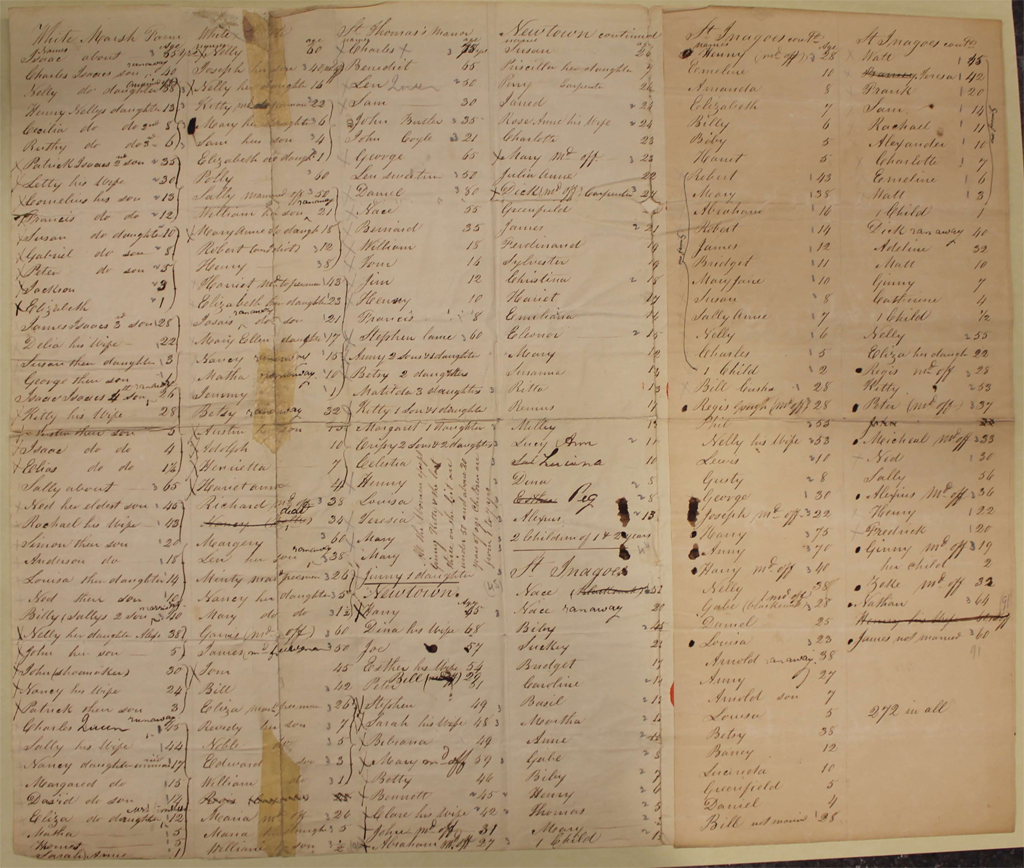

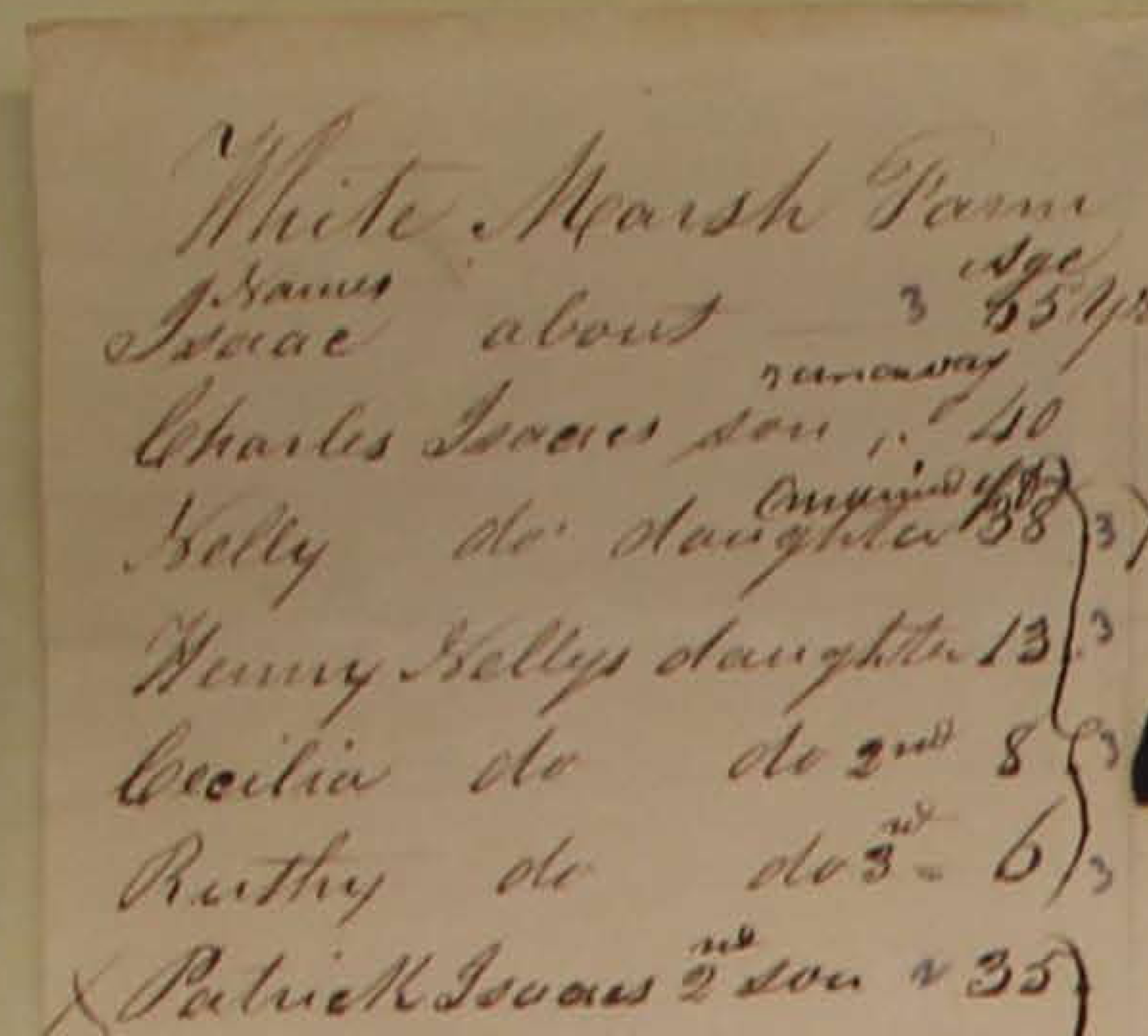

The Inventory

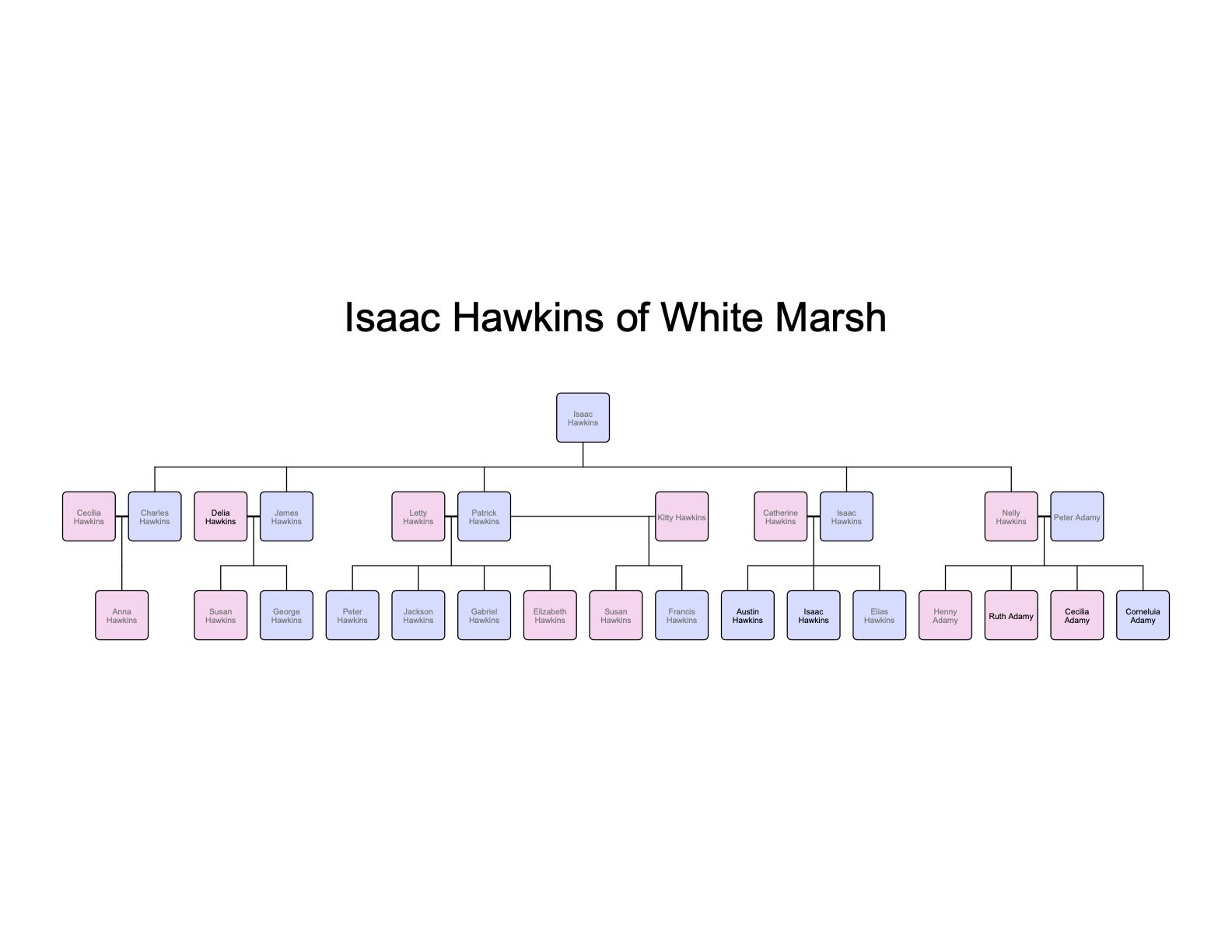

Isaac Hawkins, I

Grivel to Lancaster, November 1838

"Old Isaac is quite cheerful. Oh, said he, Fr. G. you ought to visit my wife. Mr. Kuhn said:... She is very large, indeed. How many horses said I did you want to carry her from Baltimore? A wagon & 5 horses. great laughing of Old Isaac, Miss Kitty & all. The fact is, Br. Kuhn had brought to Balt.e some hogshead of Tobacco & returning took Isaac's wife. She is not as big as old Nelly, Joe's mother. A good & well bred woman. ... Nelly, Old Isaac's daughter was sick, a very sensible woman."

Histories Accountable to the Enslaved

Saidiya Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts,” Small Axe 12, no. 2 (July 17, 2008): 2-3.

I want to do more than recount the violence that deposited these traces in the archive. I want to tell a story about two girls capable of retrieving what remains dormant—the purchase or claim of their lives on the present—without committing further violence in my own act of narration. It is a story predicated upon impossibility—listening for the unsaid, translating misconstrued words, and refashioning disfigured lives—and intent on achieving an impossible goal: redressing the violence that produced numbers, ciphers, and fragments of discourse, which is as close as we come to a biography of the captive and the enslaved.

Anthony W. Dunbar, “Introducing Critical Race Theory to Archival Discourse: Getting the Conversation Started,” Archival Science 6, no. 1 (March 1, 2006): 116, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10502-006-9022-6.

The first counterstory approach within the archives is the development of counternarratives that bring to the surface issues of racial dis-enfranchisement that are submerged based on a socio-historical archive’s mission which is likely to have been heavily influenced by marginalizing dominant culture realities. The second counterstory approach is a socio-historical archive that exists within itself as a form of counterstory to a dominant narrative.

Jessica Marie Johnson, “Markup Bodies: Black [Life] Studies and Slavery [Death] Studies at the Digital Crossroads,” Social Text 36 (2018): 71.

Histories of slavery offer digital humanists a cautionary tale, a lesson in the kind of death dealing that happens when enumerating, commodifying, and calculating bodies becomes naturalized. Doing truly embodied and data-rich histories of slavery requires similarly remixing conceptual, discursive, and archival geographies, with deliberate, pained intimacy, and, likely, some violence. But black digital practice challenges slavery scholars and digital human- ists to feel this pain and infuse their work with a methodology and praxis that centers the descendants of the enslaved, grapples with the uncomfort- able, messy, and unquantifiable, and in doing so, refuses disposability.

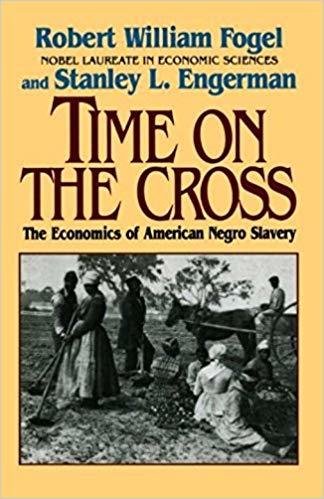

Time on the Cross

Data at Capta

Differences in the etymological roots of the terms data and capta make the distinction between constructivist and realist approaches clear. Capta is “taken” actively while data is assumed to be a “given” able to be recorded and observed. From this distinction, a world of differences arises. Humanistic inquiry acknowledges the situated, partial, and constitutive character of knowledge production, the recognition that knowledge is constructed, taken, not simply given as a natural representation of pre-existing fact.

Johanna Drucker, “Humanities Approaches to Graphical Display,” Digital Humanities Quarterly 005, no. 1 (March 10, 2011). http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/5/1/000091/000091.html

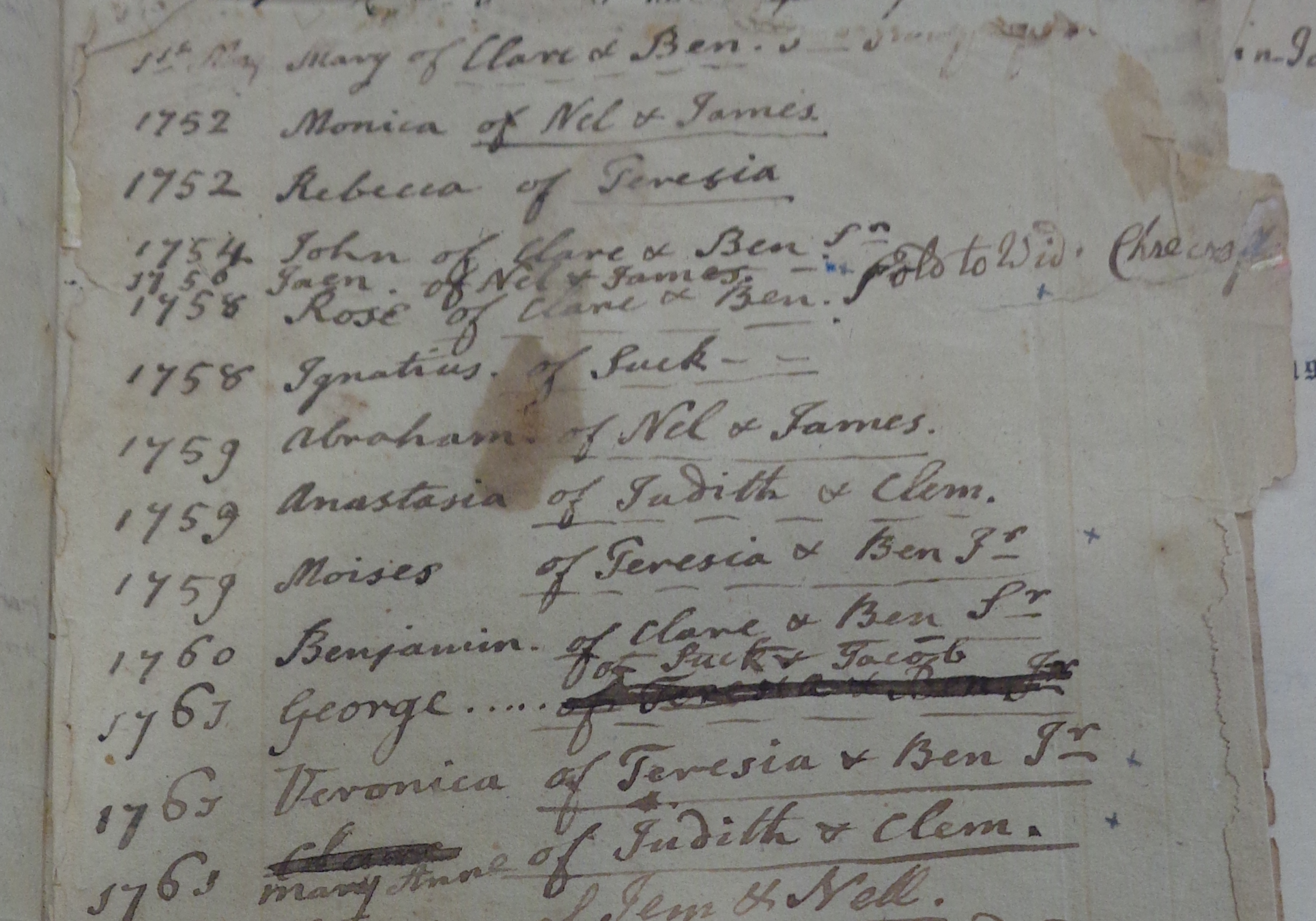

From Document to Data

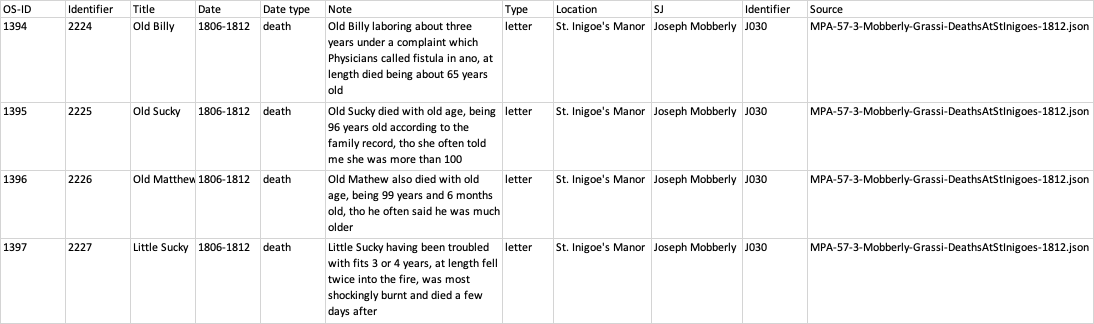

Derived Data

- Hand generated from document transcriptions

- Individuals and relationships processed to People with Unique IDs, and then de-dupped

- Appearances processed to Events with participants

- Event types: birth, baptism, marriage, death, inventory, health, sale, legal, labor, commerce, conditions, travel, punishment, run away

Research Data

The Data Model

Tidy Data

Tidy datasets are easy to manipulate, model and visualize, and have a specific structure: each variable is a column, each observation is a row, and each type of observational unit is a table.

Hadley Wickham, Journal of Statistical Software, 2014

Documentation

- Variable Choice

- Transcribed

- Controlled Vocabularies

- Imputed Fields

- Calculated Fields

- Provenance

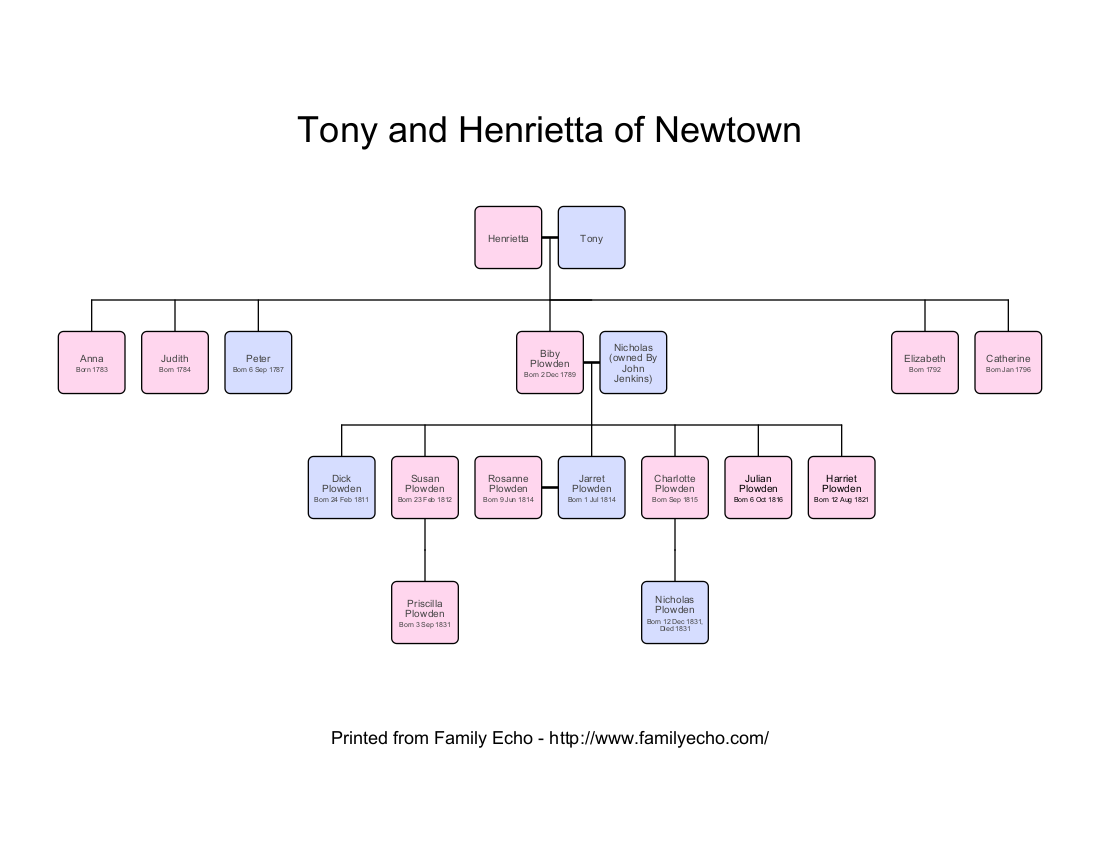

Representation and Community

Mary and Patrick Barnes, Bohemia (1790s)

- 1792 -- Jesuits purchase Mary and her children, Hannah and Isaac, from Samuel and John Fulton

- 1793 -- Pat purchases Mary and her children, making a down payment and making subsequent payments

- March 1797 -- Patrick Barnes, a blacksmith, files a freedom petition in court

- August 1797 -- Patrick Barnes is given a freedom bond based on his hire of himself from January 1 onward. He is required to settle within 10 miles from Bohemia, or forfeit L200.