Hear Us Out! Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, Pacific Islanders, and Their Music

Lesson 3:

Musical Cultures of Japanese American Incarceration Camps

Heart Mountain Relocation Center, Heart Mountain, Wyoming. "Tubbie" Kunimatsu and Laverne Kurahara, by Hikaru Iwasaki. Public Domain {{PD-US}}. National Archives.

How did incarcerated Japanese Americans use music?

What are the long-term legacies of Japanese American incarceration during WWII?

How have artists commemorated the Japanese American incarceration experience?

Musical Cultures of Japanese American Incarceration Camps

CREATIVE CONNECTIONS

HISTORY & CULTURE

MUSIC LISTENING

30+ MIN

15+ MIN

30+ MIN

"Asian Pacific American": What's in a Name?

Component 1

15–20 minutes

30 minutes+

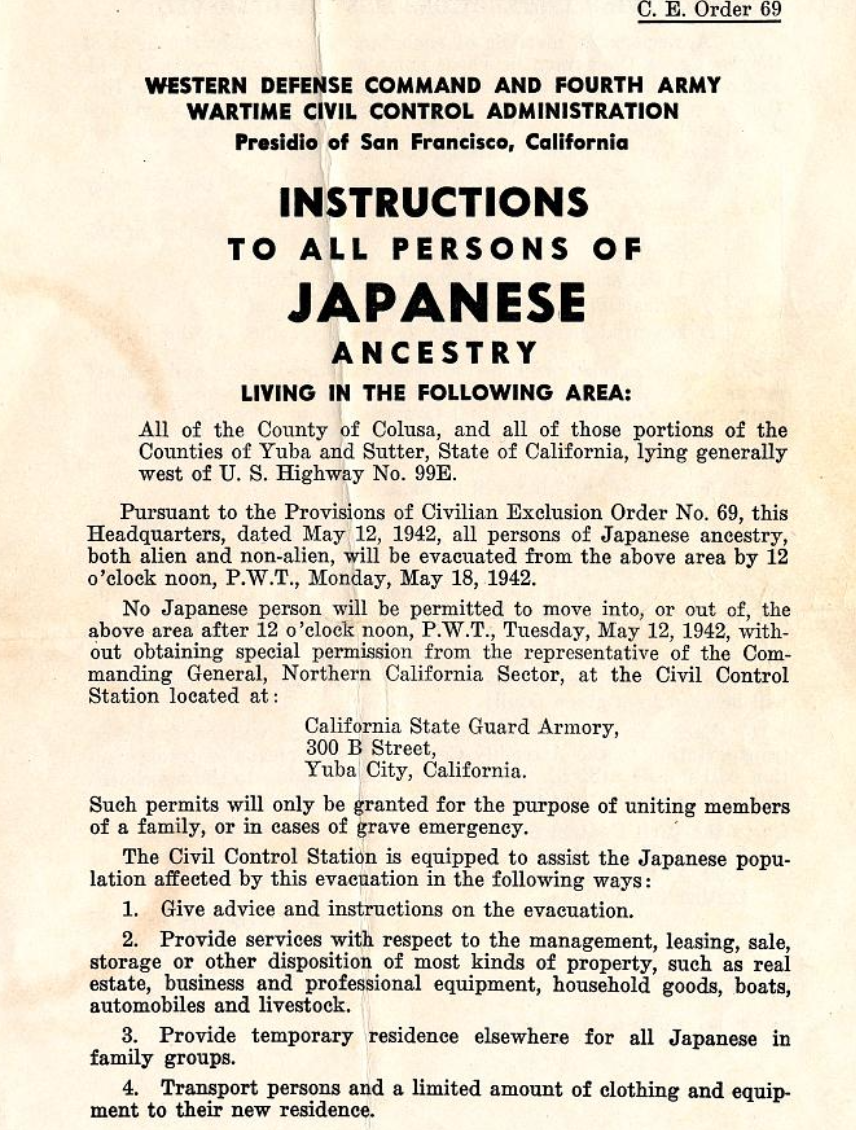

Why E.O. 9066?

Civilian Exclusion Order, by United States Army. National Museum of American History.

Omioyari

Omioyari: A Song Film by Kishi Bashi - (Official Teaser #1), directed by Kishi Bashi.

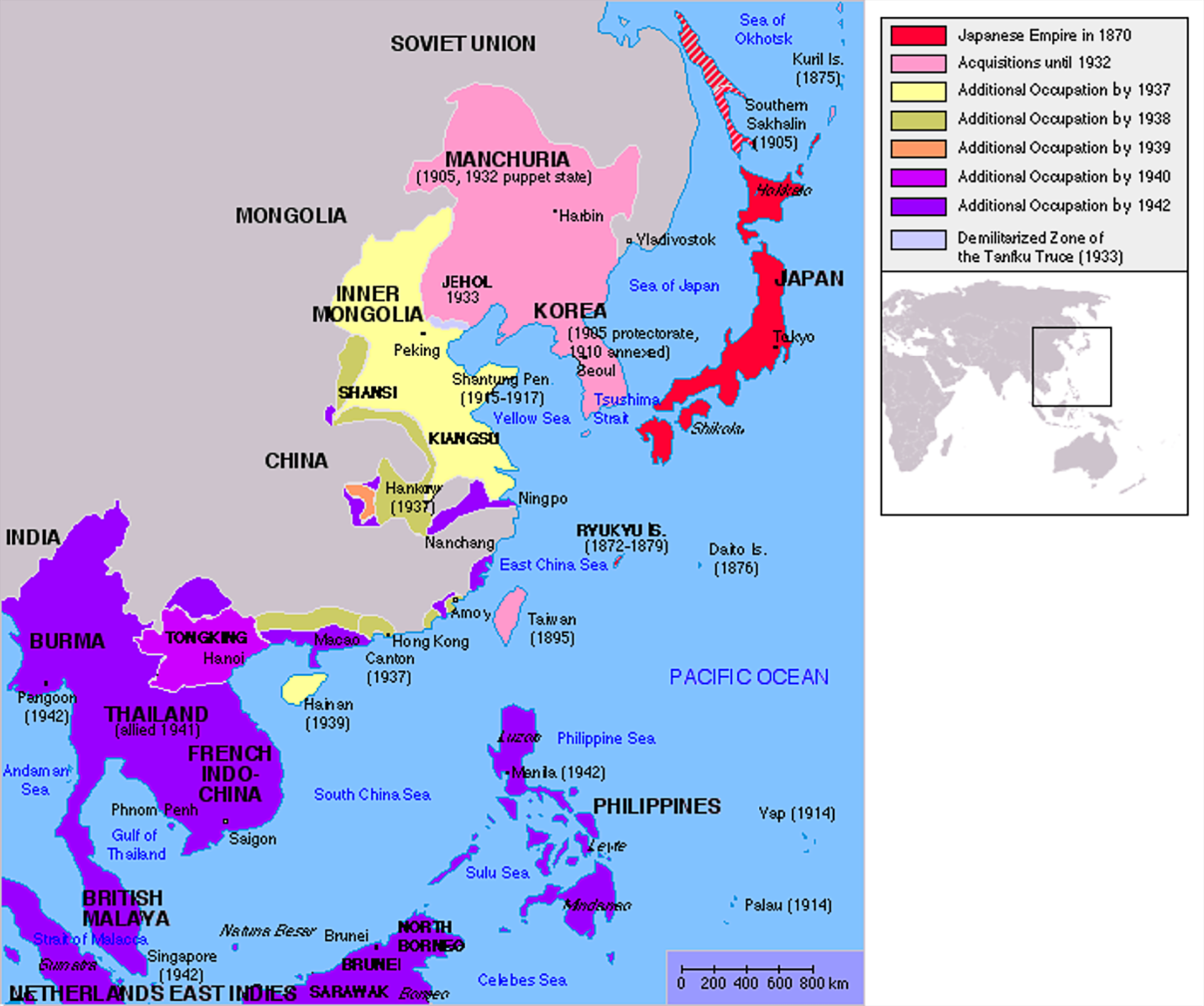

The Beginning of World War II

Many date the beginning of World War II to 1939, but it was precitated by earlier invasions:

- 1931: Japan invades an area of northeast China called Manchuria

- 1935: Italy invades Ethiopia

- 1937-38: Japan conquers most coastal areas of China

- 1938: Germany invades Austria

Japanese Empire, by Kokiri, CC-BY-SA-3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Pearl Harbor

The United States did not join World War II until Japan attacked Naval Station Pearl Harbor near Honolulu, Hawai'i on December 7, 1941, killing 2,403 Americans.

The USS Arizona (BB-39) burning after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, unknown photographer. Public Domain {{PD-US}}. National Archives.

Aftermath of Pearl Harbor for Japanese Americans

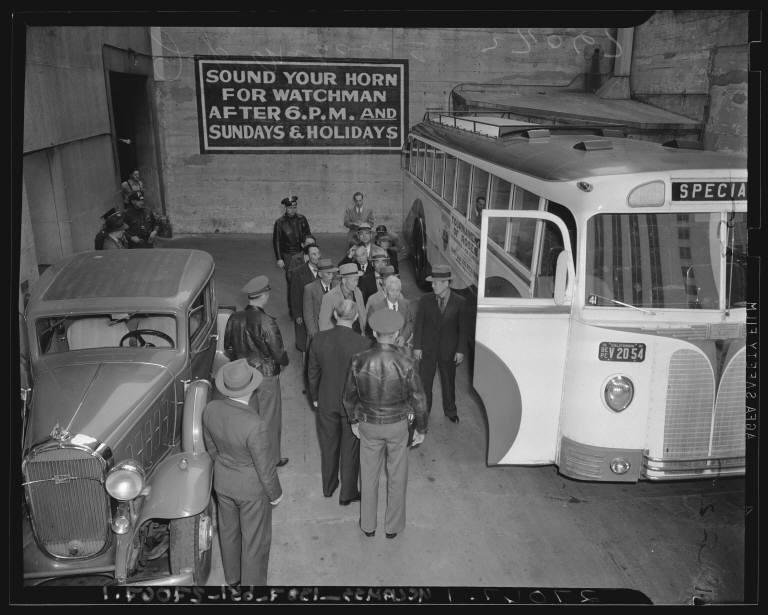

Immediately after Pearl Harbor, many Americans became very suspicious of Japanese Americans. The Department of the Treasury quickly froze the assets of all Japanese Americans, and the FBI arrested over 1,200 leaders in the Japanese American community within a few hours.

FBI Agents Arrest Japanese Civilians, unknown photographer.

CC-BY-SA-3.0, via Densho Encyclopedia.

Aftermath of Pearl Harbor for Japanese Americans

Recognizing that Japanese Americans needed to buy basic supplies, the U.S. government allowed Japanese Americans to take out some money from banks a few days later.

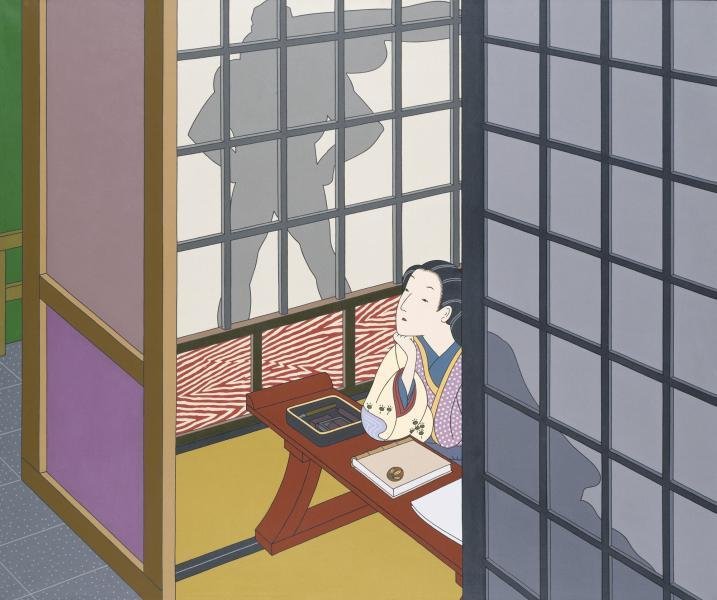

The cover image of this learning pathway portrays Toku Shimomura's gratitude about this U.S. government decision.

Diary: December 12, 1941, by Roger Shimomura. Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Aftermath of Pearl Harbor for Japanese Americans

On the right, you can see Toku Shimomura's diary entry on December 12, 1942. Here's a translation:

I spent the whole day in the house. I hear that permission has been given today to withdraw one hundred dollars from the bank. This in order to preserve the lives and safety of us enemy aliens. I felt more than ever the generosity with which America treats us.

What emotions were expressed here? In this situation, is this how you would express yourself?

Entry for December 12, 1941, Toku Shimomura Diary. National Museum of American History.

Aftermath of Pearl Harbor for Japanese Americans

Why do you think the artist used Superman in this painting?

What does Superman mean to you?

Aftermath of Pearl Harbor for Japanese Americans

In an interview with Anne Collins Goodyear, artist Roger Shimomura said that he "immediately thought of Superman when [he] thought of America." Sometimes, it stood for the American Dream, of "those rewards available for working hard and trying to attain success." At other times, what Superman represents "certainly wasn’t a flattering depiction of America."

E.O. 9066

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which gave military commanders the authority to remove any person from designated military areas.

Congress supported E.O. 9066 by authorizing a prison term and fine for those who violated the military order.

Executive Order 9066, dated February 19, 1942.

Public Domain {{PD-US}}. National Archives.

Incarceration

The head of the Western Defense Command, John L. DeWitt, struggled with his decision, but ultimately issued orders to remove 120,000 people of Japanese descent from the West Coast, two-thirds of whom were U.S. citizens.

Clip from Asian Americans (PBS Series) - Ep. 2 "A Question of Loyalty". Uploaded to Vimeo by AJSOCAL.

The Removal

Those who were forced into incarceration often had one week notice. Those who could sold their houses, farms and stores at rock bottom prices. Those who couldn't just had to leave. Pets were not allowed in camps. And they could only take what they could carry--often, just one suitcase was allowed.

If you were forced to leave with just one suitcase, what would you pack?

Wicker Suitcase, unknown maker.

National Museum of American History.

The Removal

In 2018, photographer Kayla Isomura created a multimedia exhibit that examines how the incarceration of Japanese Americans and Japanese Canadians during WWII continue to affect descendants. The core of this project involved asking fourth- and fifth- generation Japanese Canadians and Americans what they would pack if they were uprooted with almost no notice.

Self-Portrait for The Suitcase Project, by Kayla Isomura. The Suitcase Project.

The Camps

Japanese Americans on the West Coast were generally first brought to assembly centers (dots on the map), and then transported to a "relocation centers" (triangles on map). On July 31, 1943, Tule Lake (in the far northeast of California) was designated a segregation center for "disloyal" incarcerees.

Map of World War II Japanese American Internment Camps, National Park Service via Wikimedia Commons. Pubic Domain {{PD-US}}.

Life in the Camps

The camps were surrounded by barbed wire and watch towers. The barracks had no running water, and did not adequately shield residents from the harsh climate at most camps. The food in the mess halls were terrible. Medical care and sanitation were inadequate. However, there was often a sense of routine: children went to school, and adults who were U.S. citizens often had jobs.

Mess Line, noon, Manzanar Relocation Center, California, by Ansel Adams. Library of Congress.

Emphasizing American Identities

The mass incarceration of Japanese Americans was due largely to the long history of anti-Asian racism, and the resulting belief that Asians are "unassimilable."

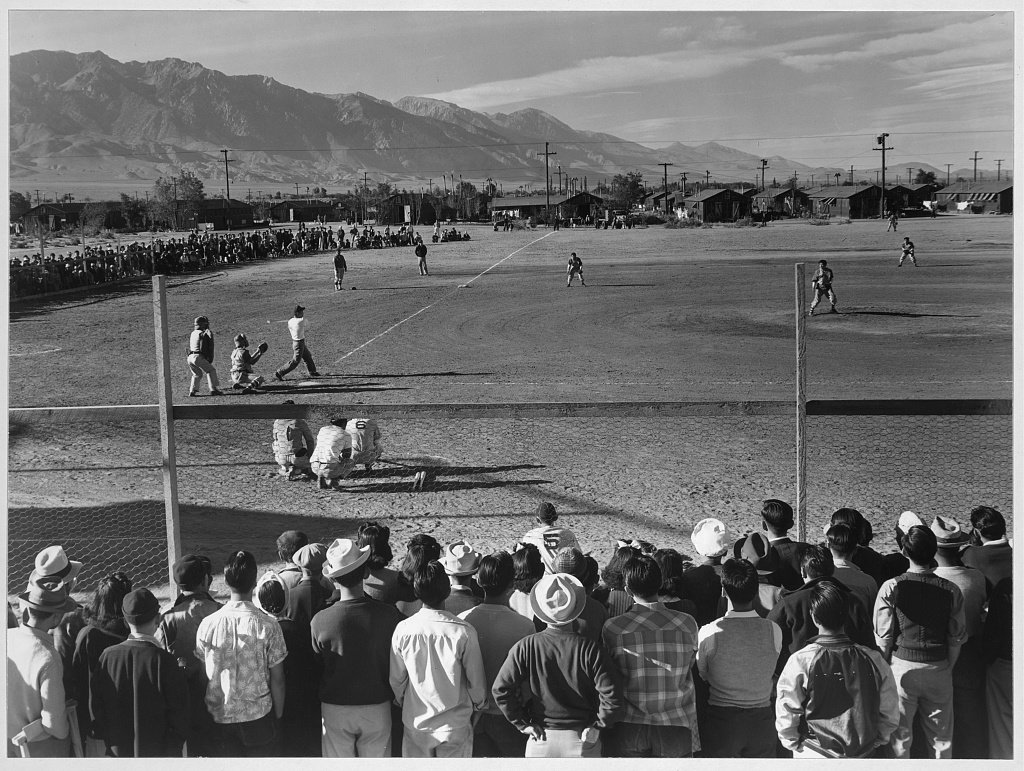

To show how misguided this belief was, many incarcerees, particularly second-generation (Nisei) and third-generation (Sansei) Japanese Americans pursued the most iconic American activities in camp. One of them was baseball.

Baseball Game, Manzanar Relocation Center, Calif. by Ansel Adams. Library of Congress.

Emphasizing American Identities

All ten incarceration camps had big bands. Joy Terakoa was incarcerated at Heart Mountain Relocation Center in Wyoming, and regularly sang with the George Igawa Band there. In this short documentary, Julian Saporiti and Erin Aoyama interviewed Joy in Hawai'i and played a concert with her.

Another was jazz.

For Joy, produced by Omoiyari Song Film. Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation.

Discussing "American" Identities

Under what circumstances (if any) would you want or feel the need to perform your American-ness (or some other identity) in public?

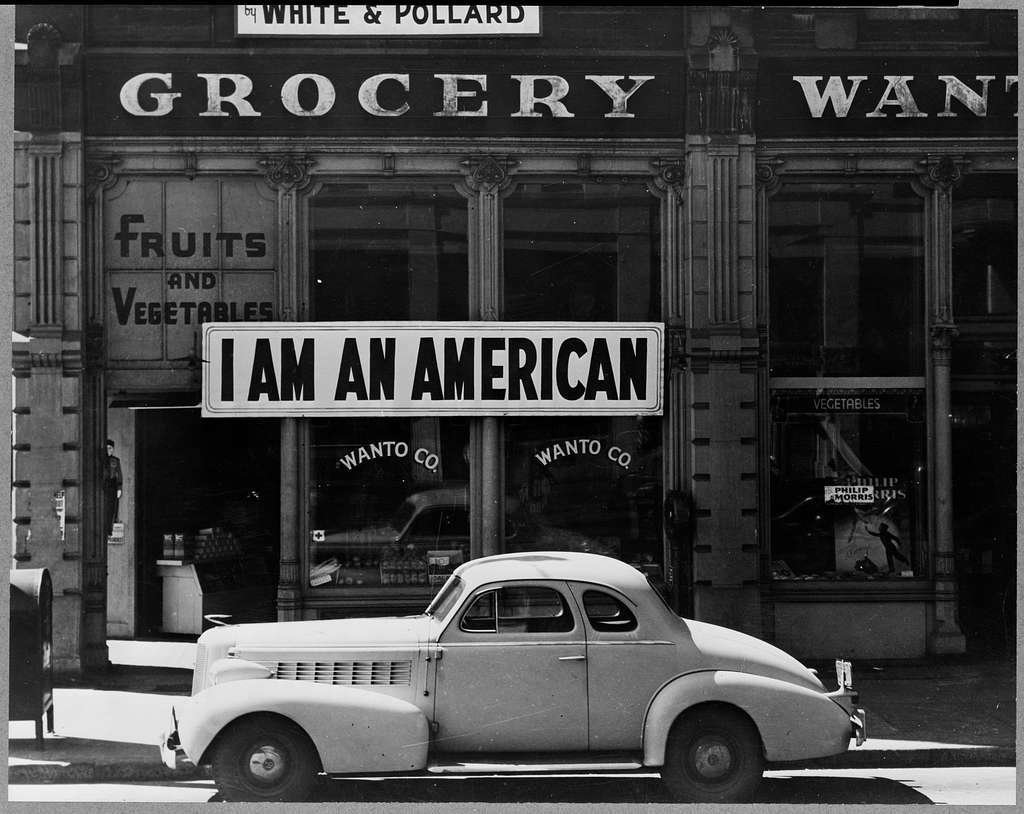

Oakland, California, Mar. 1942. A large sign reading "I am an American" placed in the window of a store, by Dorothea Lange. National Archives.

If you were forced to show off your American-ness (or some other identity), how would you do it?

Revitalizing Japanese Traditions

Ironically, the incarceration camps also strengthened traditional Japanese arts and practices. With so many Japanese Americans gathered together in one place, incarcerees were able to find teachers on Japanese musical instruments, dance, theater, flower arranging, and even tea ceremony.

Hidden Legacy: Japanese Traditional Performing Arts at the WWII Internment Camps, produced by Shirley Kazuyo Muramoto. Public Domain {{PD-US}}. Murasaki Productions LLC.

Long-Term Impacts: Property

Japanese Americans lost approximately 75% of their property during incarceration. Exact totals are impossible to calculate, but the Commission on the Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians estimated the community's loss to be between $2 billion and $5 billion in 2017 dollars.

Vandalism of Japanese American property, unknown photographer.

Courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration.

Long-Term Impacts: Health and Community

Due to the experience of trauma, incarceration had a major impact on health. A study by Gwendolyn Jensen showed that suicide rates for Japanese Americans were as much as four times higher after the war than before.

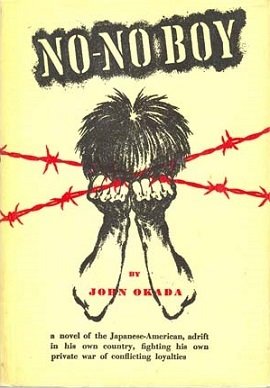

The incarceration experience also led to severe tensions within the Japanese American community as well as intergenerational trauma.

First edition cover, 1957, unknown artist. CC-BY-SA-3.0, via Densho Encyclopedia.

Legality of Detention?

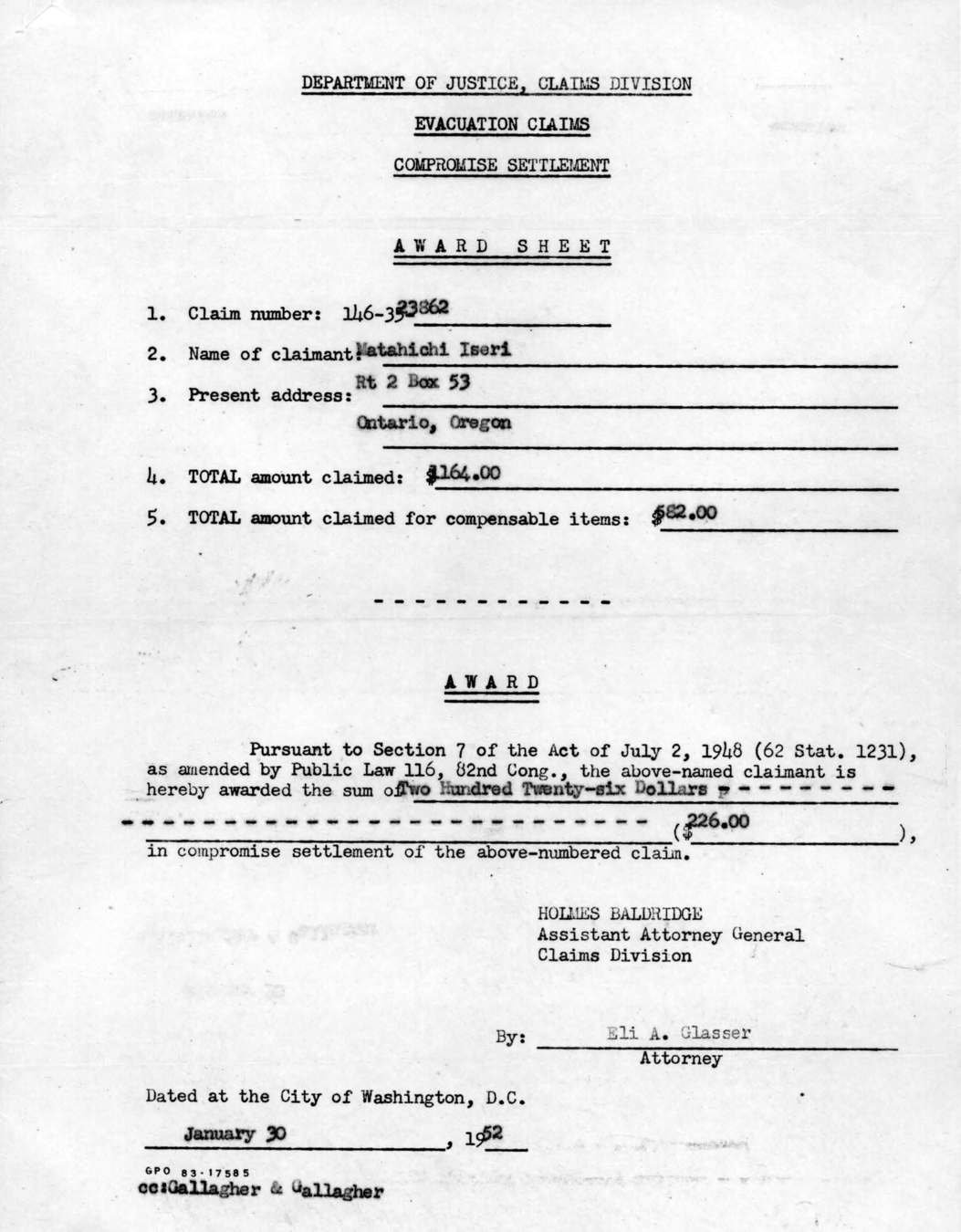

Ever since E.O. 9066 was implemented, Japanese American activists have challenged the legality of their detention, fought to restore their constitutional and civil rights, and sought official apologies and monetary compensation from the U.S. government.

Congress passed the Japanese American Evacuation Claims Act in 1948, which ultimately paid Japanese Americans $38 million, a small fraction of the actual property the community endured.

Department of Justice Evacuation Claims Award Sheet, Jan. 30, 1953, sent to Ontario, Oregon, courtesy of Densho. The Yamada Family Collection.

Redress Movement

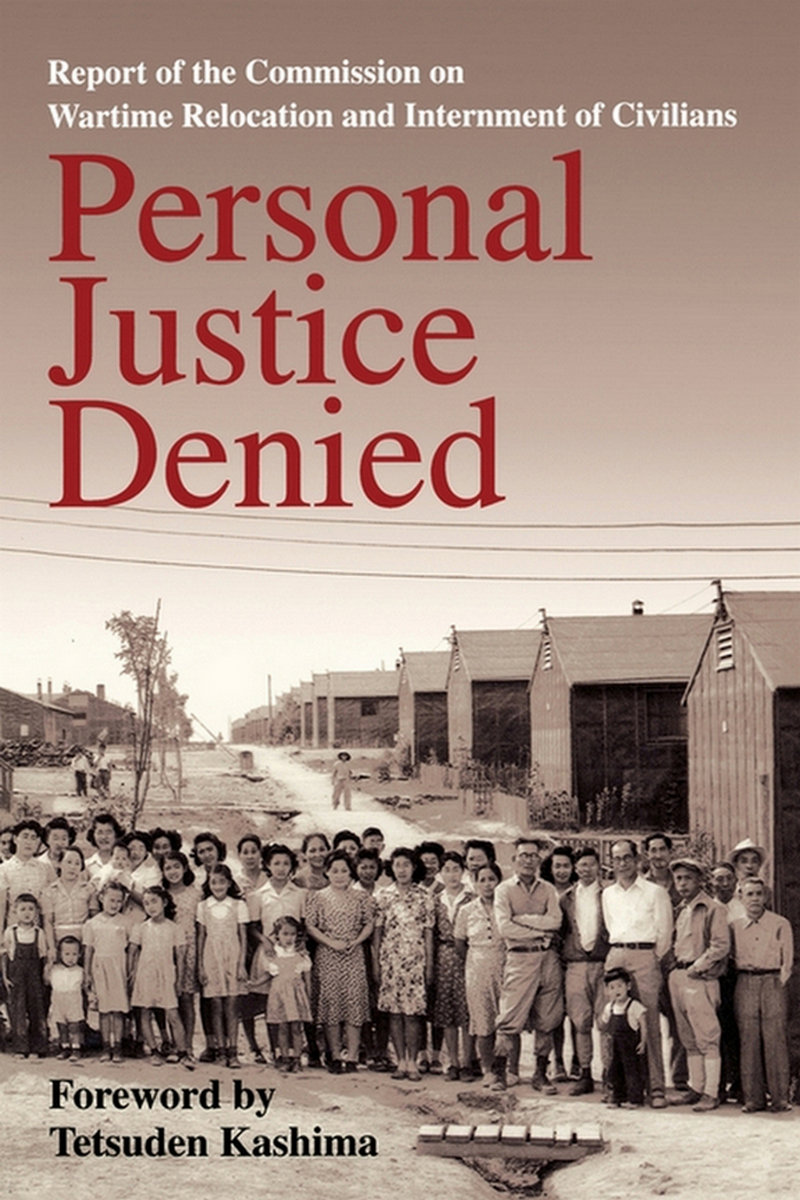

This led to the formation of Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC) in 1980.

- This nine-member commission spent two years hearing testimonies from 750+ witnesses, researching archival sources and analyzing scholarship on the incarceration. It ultimately issued a 467-page report (right) in December 1982.

Inspired by the civil rights and antiwar movements, the Redress movement gained steam in the late 1960s and 1970s.

Personal Justice Denied, Commision on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians. Univesity of Washington Press

Civil Rights Act of 1988

- Acknowledging the injustice of the incarceration

- Issuing an official apology

- Paying each surviving incarceree $20,000

- Establishing an education fund to inform the public about the truth of the incarceration

- Discouraging similar future injustices

President Reagan's Remarks and Signing Ceremony for the Japanese-American Internment Compensation Bill. Reagan Library.

The CWRIC Report became the basis of the Civil Rights Act of 1988, which included:

Discussing Reparations

To what extent can the Redress Movement and the Civil Rights Bill of 1988 inform the ongoing debate about reparations for descendants of people who were enslaved or other victims of state-perpetrated injustices?

Reparations, photo by Tyler Merbler, CC BY 2.0, via Flickr.

Learning Checkpoint

- What led to the incarceration of 120,000 Japanese and Japanese Americans who lived on the West Coast during WWII?

- Are there any parallels between the Japanese American incarceration during World War II and current events?

- What was life like in Japanese American incarceration camps during WWII? What kind of music did people make?

- What are some key long-term impacts of the Japanese American incarceration camps?

End of Component 1: Where will you go next?

Creating a Monument

Component 2

15+ minutes

Animals in War Memorial, London, photo by Iridescenti. CC BY SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Monuments are structures or artworks that commemorate a person, event, or social group.

What are monuments?

Sometimes, monuments support certain historical narratives and downplay others, and they often take up important spaces. Many are significant tourist attractions as well as sites of contestation.

RVA Counter-Protests Against Neew-CSA, photo by Mobilus in Mobili. CC BY SA 2.0, via Flickr.

Why do we create monuments? What purposes do they serve?

Who benefits from monuments? Who might be harmed?

The Purpose of Monuments

The Tejano Monument, a sculpture on the Texas Capitol Grounds, photo by Carol M. Highsmith. CCO 1.0. Library of Congress..

Commemorating the Japanese American Incarceration through Monuments

Left: Japanese American Memorial to Patriotism During World War II, photo by David, CC BY 2.0, via Flickr. Right: Manzanar Shrine, photo by Daniel Meyer, CC-BY-SA-3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Creative Activity

- As a class, discuss monuments that are in your neighborhood or city. If time permits, complete pp. 2-4 of Monument Lab's "Field Trip" Exercise.

- Choose a person, event, social group or issue to which you you want to draw attention or commemorate.

- Design a monument for your chosen subject. What will it look like? What words will be on it? Where will it be? How and why did you make these decisions?

Monument devant le Siège Social de la Commision Scolaire de Portneuf - Donnacona, photo by Sylvainbrousseau, CC-BY-SA-4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Learning Checkpoint

- When you create a monument, what are some key decisions that need to be made? How would you make these decisions?

- What purposes do monuments serve?

- How might certain people or groups benefit from monuments, and how might other people or groups be harmed?

End of Component 2: Where will you go next?

Musical Commemorations

Component 3

30+ minutes

Kim Tran Sings a Vietnamese Folksong "Cò Lả" Accompanied by a Bronze Gong. Diasporic Vietnamese Artists Network.

Purposes of Musical Commemoration

Music is used to commemorate major events and can serve many purposes, including:

- Individual and community healing

- Promoting certain narratives/actions

- Education

- Fundraising

- Building community

- Providing space for reflection

A Marine Corps Bugler, photo byTerry A. Cosgrave. National Archives. Public Domain {{PD-US}}.

Examples of Musical Commemoration

"America: A Tribute to Heroes" was a benefit concert organized in the immediate aftermath of the 9/11 attacks. Bruce Springsteen sang the opening song.

The show honored those involved in rescue operations, raised funds for victims and their families, and worked to raise the country's spirits.

Bruce Springsteen - America: A Tribute to Heroes, uploaded by Glen Campbell and Much Much More.

Examples of Musical Commemoration

The photo on the right shows Kim Tran singing the Vietnamese folksong “Cò Lả” accompanied by a bronze gong at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, DC. The song describes a crane flying over green fields while missing and remembering home.

Examples of Musical Commemoration

The George Floyd Foundation (GFF) organized this commemorative concert to mark the 1st anniversary of Floyd's death.

According to GFF, the concert served as a "reminder of the continued fight for #JusticeforGeorge and so many others who have lost their lives unjustly."

George Floyd Commemorative Concert. Fountains of Praise.

Discussion: Purposes of Musical Commemoration

Try to remember the last time you heard music at a commemorative event/ceremony (e.g., funerals, anniversaries of tragedies, celebrations of certain achievements).

The Jazz Funeral for Democracy in New Orleans, 2005. Photo by Bart Everson, CC BY 2.0, via Flickr.

What purposes did that music serve? Did you think it was appropriate? If you were in charge, would you have changed it in any way?

Commemorating the Incarceration Experience

The Japanese American incarceration has been the subject of many musical works. Some of the key reasons are:

- The activism of survivors

- The continuing impact of the incarceration on Asian Americans

- The continuing relevance of debates that led to the incarceration

In America (Excerpt). Los Angeles Master Chorale.

Commemorating the Incarceration Experience

Explore all or some of them depending on the time you have available to teach this component.

The next series of slides (46-57) explores three additional examples of musical works that commemorate the Japanese American incarceration experience.

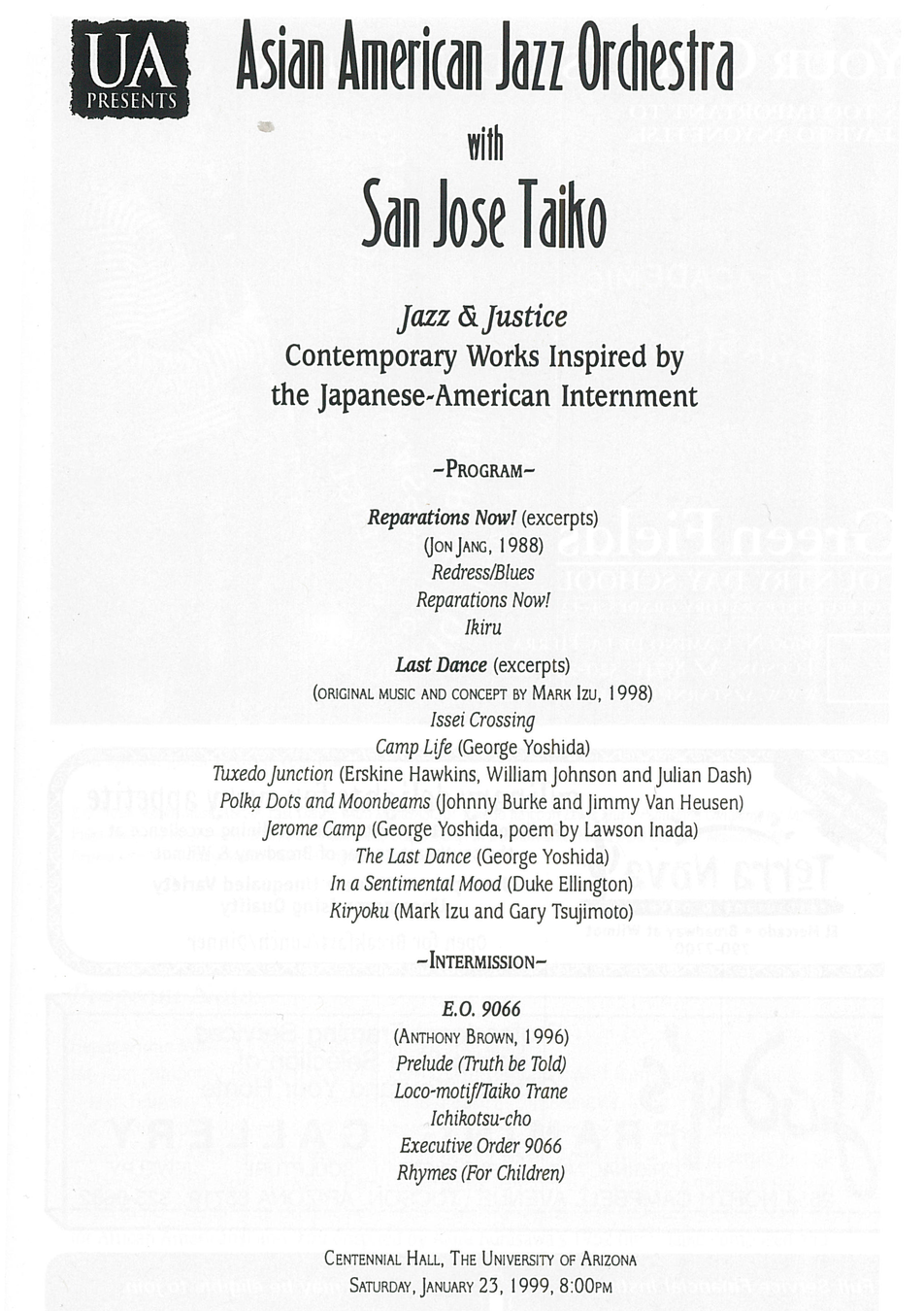

Anthony Brown, E.O. 9066

Composer, bandleader, percussionist and scholar Anthony Brown was a member of the cohort of musicians who developed what is often called "Asian American Jazz" in the 1980s.

MAARC Oral History: Anthony Brown, Part 3. Music of Asian America Research Center.

These musicians' styles varied, but all tried to combine African American and Asian American traditions in a way that was politically liberatory.

Anthony Brown, E.O. 9066

The son of a Japanese mother and a father of mixed Choctaw (Native American) and African American descent, incarceration camps were not a part of Brown's family history.

Recognizing that he, his mother, his children and his grandchildren would be incarcerated if E.O. 9066 passed today, he hoped to educate everyone about this history.

Program of Works about the Japanese American Incarceration at the University of Arizona, 1999. Courtesy of Anthony Brown and the Music of Asian America Research Center.

Anthony Brown, E.O. 9066

The incarceration of 2,200 Latin Americans of Japanese descent is a relatively unknown aspect of this history. Ever the educator, Brown decided to raise this issue by making the last movement of E.O. 9066 a rumba.

Entitled "Rhymes (for Children)," the movement we will listen to was inspired by photos of children who were caught up in the incarceration.

What instruments and sounds do you expect to hear?

Boys softball team from Block 22 with Coach Kanenori Jack Takayama, by George Hirahara. George and Frank C. Hirahara Photograph Collection of Heart Mountain, Wyoming, Washington State University Libraries' MASC.

Anthony Brown, E.O. 9066

What other feelings do you feel? Why?

What Latin American, African American and/or Asian influences do you hear?

Does a sense of hope come across?

Anthony Brown, E.O. 9066

E.O. 9066 (1996) incorporated a Chinese melody entitled "The General's Order" (to depict the actions of General DeWitt), an 11th-century Japanese gagaku melody (to depict first-generation immigrants), taiko, and a variety of Asian and Middle Eastern wind instruments into a loose jazz framework.

Left: San Jose Taiko at Yerba Buena Center, by Bob Hsiang. Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center.

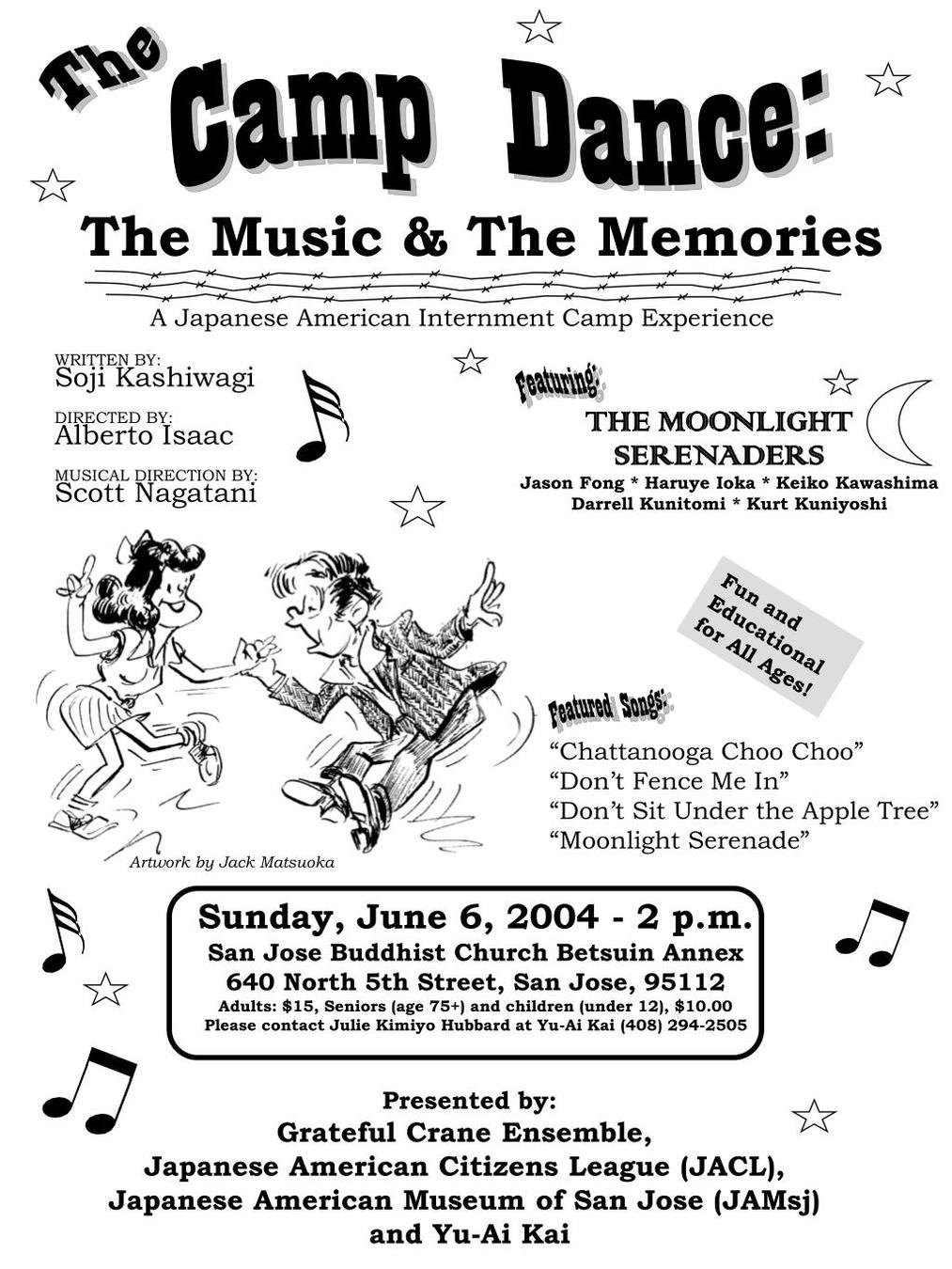

Soji Kashiwagi, Camp Dance (2003)

This group started in 2001 as a theater troupe that entertained and served first- and second-generation Japanese Americans at Keiro Retirement Home in Los Angeles.

Grateful Crane Ensemble.

Soji Kashiwagi is a founding member of the Grateful Crane Ensemble.

Soji Kashiwagi, Camp Dance (2003)

Historical context plays a huge role in artistic production.

During the early part of the Redress Movement, Japanese American activists had to show the country how unjust the incarceration was. To get attention, they (including Soji's father, Hiroshi Kashiwagi) produced art that expressed anger.

Poems by Hiroshi Kashiwagi. Grateful Crane Ensemble.

Soji Kashiwagi, Camp Dance (2003)

In an interview with me, Kashiwagi said, "After a while, you get tired of getting pounded over the head with anger and injustice. You can only take so much of that."

In the 1990s, the focus shifted from anger to education. This anger was dialed down a bit, but—as Anthony Brown's E.O. 9066 shows—it is still there. As of 2003, things had changed even more.

Soji Kashiwagi.

Soji Kashiwagi, Camp Dance (2003)

By creating a musical about one of the happiest activities in camp, he hoped to build a safe space where the older generations can share their experiences, and where younger ones could ask questions they had never dared to ask.

Kashiwagi felt that what he needed to do was to help the survivors heal and to repair intergenerational tensions within the community that was caused largely by PTSD.

The Camp Dance Publicity Poster., by unknown designer.

Soji Kashiwagi, Camp Dance (2003)

In this musical, Kashiwagi heightened audiences' sense of belonging by naming specific bands and events at various camps.

What other methods did Kashiwagi use to heighten audiences' sense of belonging? How did he convey that campers held different beliefs?

The Camp Dance: The Music and the Memories, uploaded by Emily Kuroda.

Fort Minor, "Kenji" (2005)

Mike Shinoda (b. 1977) is co-founder of Linkin Park, and founder/leader of the hip hop group Fort Minor. His father's family was incarcerated during WWII.

The song "Kenji" is based on an interview with his father and an older aunt. His father went to camp when he was a toddler, but his aunt was in her 20s. This podcast excerpt provides more background about the song.

Fort Minor - The Rising Tied (Audio Commentary). iHeartRadio.

Fort Minor, "Kenji" (2005)

Shinoda's listeners—rock and hip hop fans—are very different from Kashiwagi's. By and large, they might have learned something about the incarceration in school, but they probably didn't know anyone who lived through that experience. "Kenji" personalized the camp for these fans.

The audiences that artists want to reach also play significant roles in artistic production.

Fort Minor - Kenji Music Video, uploaded by FortMinorSongs.

Fort Minor, "Kenji" (2005): Interview Version

To make the incarceration experience even more authentic for his fans, Shinoda released a version in which he does not rap. The only words you hear are clips from the interview he did with his father and aunt.

Fort Minor - Kenjo (Interview Version), uploaded by al112v5.

Which version do you think better conveys the intent of the song? Why?

Reflection (Optional)

Of the four songs you listened to in this component:

- Anthony Brown's "Rhymes (for Children)" from E.O. 9066

- Soji Kashiwagi's Camp Dance

- Fort Minor's "Kenji"

- Fort Minor's "Kenji (Interview Version)"

How did the intended audience change how the artists conveyed the Japanese American incarceration experience?

Which is most meaningful to you? Why?

Which one do you like the most? Why?

Optional: More Attentive Listening

Listen to and compare two additional tracks from the Smithsonian Folkways catalog that commemorate the Japanese American incarceration experience:

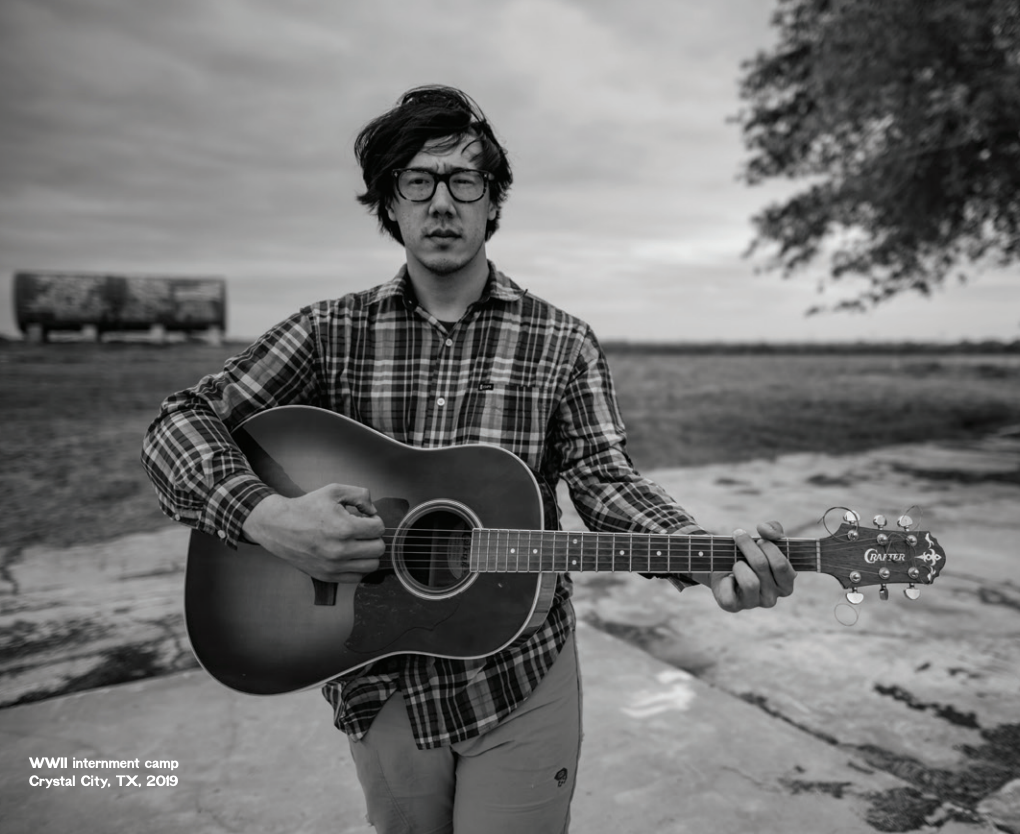

"The Best God Damn Band in Wyoming" by Julian Saporiti (Album: 1975).

"120,000 Stories" by Nobuko Miyamoto (Album: 120,000 Stories).

Learning Checkpoint

- What purposes can musical commemoration serve?

- How did the composers/songwriters featured in this component use music elements and expressive qualities to convey intent?

- How can different audiences affect the type of commemorative music a composer/songwriter creates?

End of Component 3 and Lesson 3: Where will you go next?

Lesson 3 Media Credits

Audio courtesy of

Smithsonian Folkways Recordings

Video courtesy of

Advancing Justice - LA

Fort Minor?

Grateful Crane Ensemble

Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation

Murasaki Productions LLC

Music of Asian America Research Center

Omoiyari/Kishi Bashi

Images courtesy of

Densho Encyclopedia

Diasporic Vietnamese Artists Network

Grateful Crane Ensemble

Library of Congress

National Archives

National Museum of American History

National Park Service

Music of Asian America Research Center

Smithsonian American Art Museum

The Suitcase Project

Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center

Heart Mountain Interpretative Center

© 2022 Smithsonian Institution. Personal, educational, and non-commercial uses allowed; commercial rights reserved. See Smithsonian terms of use for more information.

This project received Federal support from the Asian Pacific American Initiatives Pool, administered by the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center.

For full bibliography and media credits, see Lesson 3 landing page.