Hear Us Out! Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, Pacific Islanders, and Their Music

Lesson 8:

Cultural Preservation and Adaptation:

Kulintang, Kundiman, and Pinpeat in the US

Cambodian American Artists Rehearse for a Performance, by Sojin Kim. Smithsonian Folklife Magazine.

Lesson 8:

Cultural Preservation and Adaptation: Kulintang, Kundiman, and Pinpeat in the U.S.

Are there right or wrong ways to change or adapt cultural practices?

How do immigrants and refugees adapt or transform their cultural practices or art forms in new spaces?

Cultural Preservation and Adaptation: Kundiman and Pinpeat in the U.S.

Preserving and Sustaining Cultural Heritage: Kulintang and Kundiman

Component 1

30+ minutes

"Iskwelahang Pilipino Rondalla at Struck & Plucked, U-M." Uploaded by Center for Southeast Asian Studies University of Michigan.

Rondallas

A rondalla (or rondalya) is an ensemble of plucked string instruments, originally from Spain. It was introduced to the Philippines during the early Spanish colonial period. Over centuries, Filipinos have adapted and localized this tradition.

Tagumpay Mendoza De Leon: NEA National Heritage Fellows Tribute Video. National Endowment for the Arts.

Filipino Americans have been forming rondallas at least since 1904. Since then, they have further adapted this tradition.

What are some examples of traditions in your home/communities?

What Is Tradition?

The Cambodian-American Heritage Dancers and Chum Ngek Ensemble, by Stephen Winick. Library of Congress.

It's complicated...

What Is Tradition?

- Defined and constructed by people and society

- Constantly changes and adapts as people encounter different ideas, experiences, and social dynamics

Traditions, created by tupungato. Via DepositPhotos.

Do you agree or disagree with Hobsbawm?

Discuss: What Is Tradition?

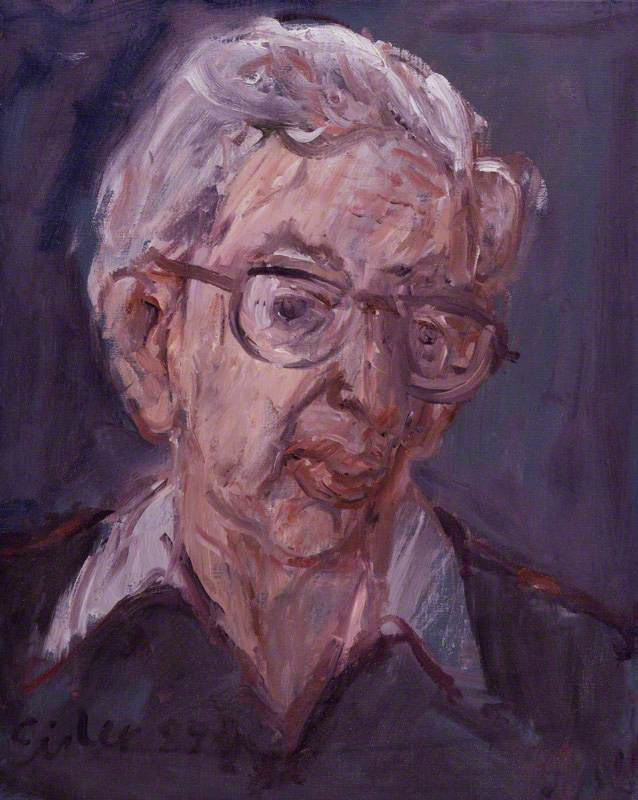

Eric John Ernest Hobsbawm, by Georg Eisler. National Portrait Gallery, London.

Economic theorist Eric Hobsbawm argued traditions are "somewhat invented."

When life changes, what happens?

When people move to a new country, what do they do with their cultural traditions? Here are some possibilities:

- Continue their practices with no or little change.

- Adapt their practices to their new environment.

- Create infrastructure so their traditions can continue.

- Reject their homeland's cultural practices.

To discuss these options, some terms are useful...

Preservation vs. Sustainability

Can you think of an example of cultural preservation? Cultural sustainability?

Preservation involves reproducing and maintaining cultural practices and traditions in one specific state or condition.

Sustainability leaves the opportunity for cultural practices and traditions to grow and change in response to their environments.

Third Space and Hybridity

Can you think of an example of third space?

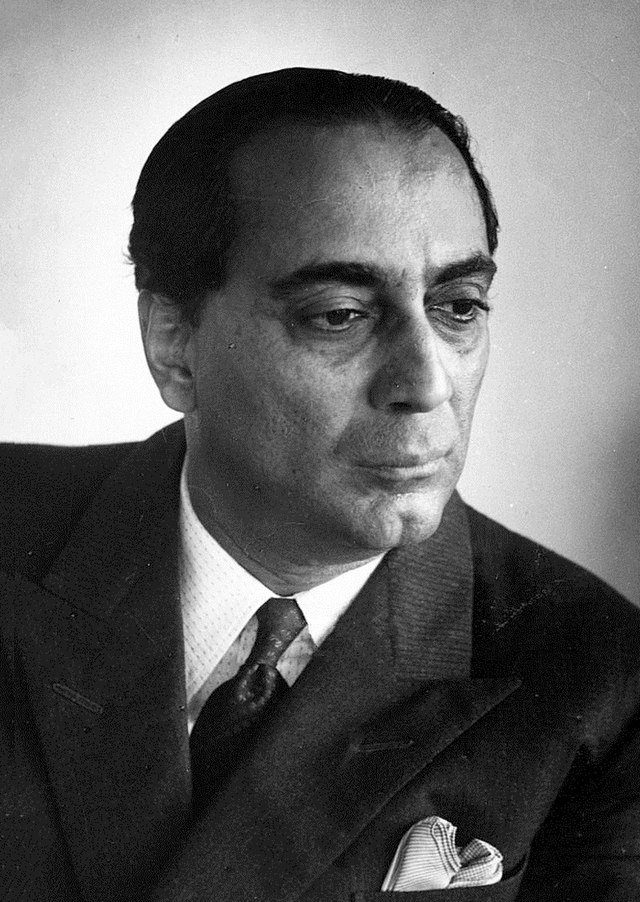

Third Space is a term coined by Homi Bhabha that discusses hybridity. When two or more traditions come together to create something new, a "third space" is created. This "third space" is an in-between space. For Bhabha, it is both unstable and full of possibility.

Homi Jehangir Bhabha 1960s, unknown photographer. Public Domain {{PD-US}}, via Wikimedia Commons.

Exile Nostalgia

Do you know people who are experiencing exile nostalgia?

Exile Nostalgia: term that applies primarily to people who were forced to move and unable to go back to their homeland because of war, violence, politics, identity-based persecutions, etc. Exile nostalgia involves feelings of loss and mourning. People experiencing exile nostalgia often construct an idealized homeland in their lives through artifacts, storytelling, social gatherings and the arts.

The remainder of this lesson examines how music traditions and cultural practices in Asian America have responded (and continue to respond) to these forces.

What Is Tradition?

In sum, traditions constantly change, adapt, and sustain in relation to different organizations, institutions, governments, regimes, rulers, and major events.

Filipino American Immigrants and Music

Ever since Filipinos began coming to the U.S. in large numbers in the early 20th century, they have used music in a variety of ways, including:

- Playing American popular music both within and outside Filipino American communities

- Using music making as a tool for remembering, placemaking, and community building

Harry and His Band in San Diego, CA, unknown photographer. Courtesy of Rudy P. Guevarra Jr., Journal of San Diego History.

What is Kulintang?

Kulintang became established in the U.S. largely through the work of Filipino American, Danongan "Danny" Kalanduyan. He moved to the U.S. in 1976 to teach at the University of Washington, and then relocated to California in the 1980s.

Kulintang is a part of the gong-chime culture of Southeast Asia. It consists of a row of small gongs which generally plays the melody, accompanied by several drums and gongs.

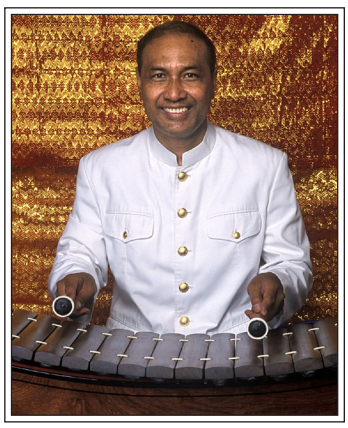

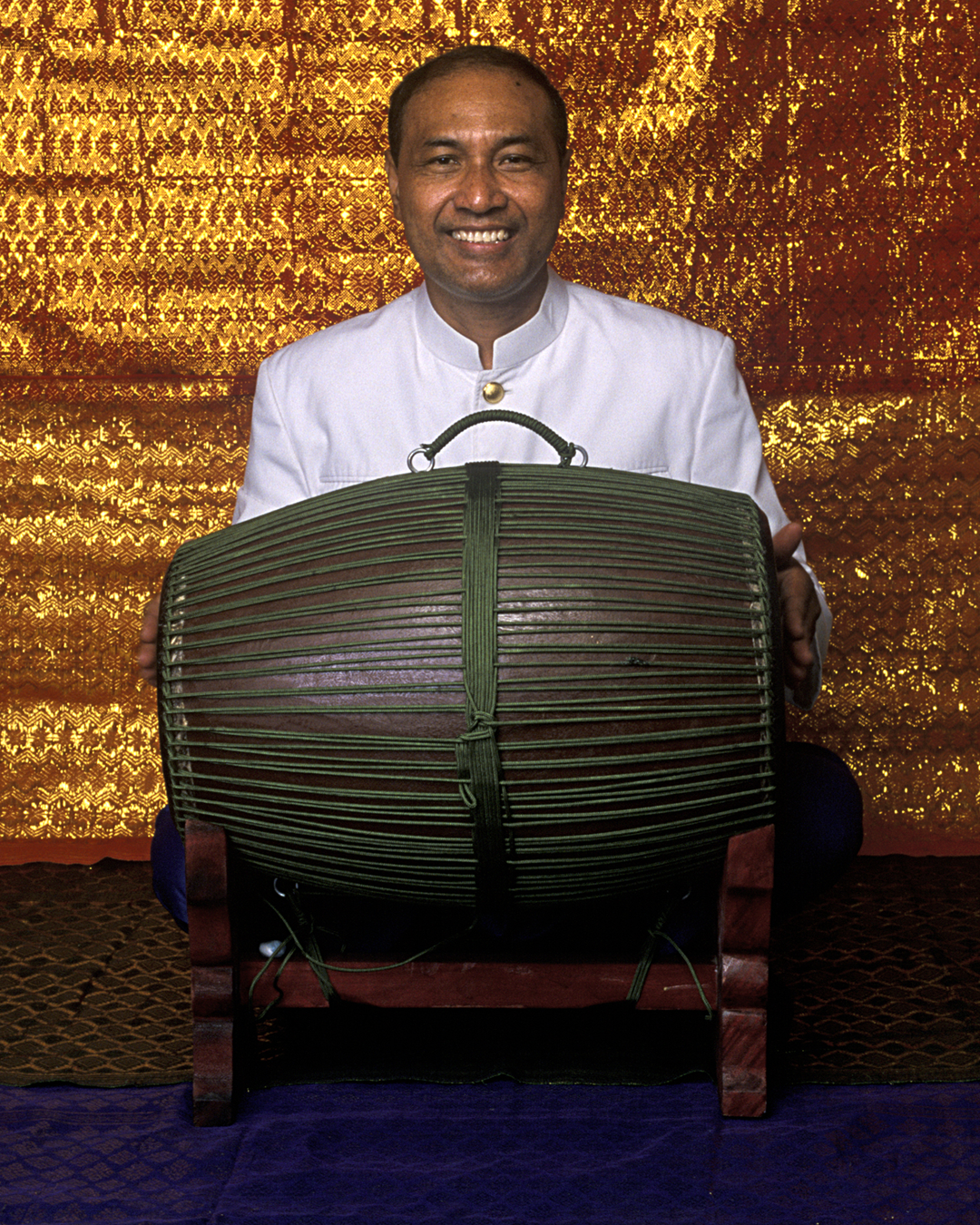

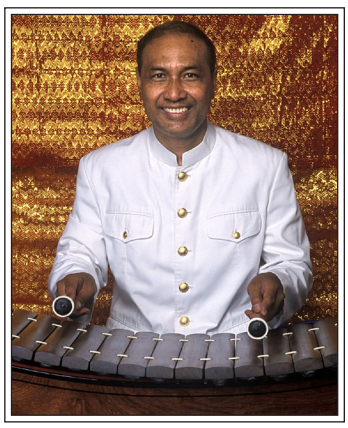

Danny performing at Tufts University, 2008, by Joyce Torres. Smithsonian Folkways Recordings.

"Kapagonor," performed by Danongan Kalanduyan and the Palabuniyan Kulintang Ensemble.

Kulintang: A More Experimental Approach

While Kalanduyan himself focused primarily on teaching traditional kulintang, he mentored performers from many different musical backgrounds.

Many of these students--and other members of the Philippine Diaspora--created very interesting hybrids. Kalanduyan himself performed on several recordings.

This example, "World Gong Crazy," features the electric music duo DATU. You will hear the high-pitched kulintang instrument called the sarunay.

Sarunay, by Philip Dominguez Mercurio. CC BY-SA-3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

What is Kundiman?

Kundimans are often patriotic songs disguised as love songs.

Kundiman developed in the Philippines around the turn of the 20th century--that is, towards the end of Spanish colonization and the beginning of U.S. colonization.

Kundiman is another example of a popular Filipino music tradition that has been preserved, sustained, and adapted in the United States.

"Nasaan Ka Irog," performed by Sylvia La Torre. ℗ 1994 Allan J. Villar / Synergy

"Bayan Ko"

Today, you will experience "Bayan Ko" ("My Country"): One of the most famous kundimans.

Bayan Ko, photographed by NCCA Official. CC BY-NC-SA-2.0, via Flickr.

- It was originally a song with Spanish lyrics

- The version most often heard today dates from 1929–and has Tagalog lyrics.

- During the the Marcos Dictatorship (1965-86), "Bayan Ko" became a favorite song of protesters, leading the Filipino government to ban public performances in 1972.

"Bayan Ko" and the Marcos Dictatorship

In the early 1970s, two organizations (one from the U.S. and one from the Philippines) recorded an album called Philippines: Bangon! Arise! This album is now part of the Smithsonian Folkways collection.

- It contains songs that protested Ferdinand Marcos’ military dictatorship and the role of the American government in backing his regime (including "Bayan Ko").

Does the song sound patriotic? Why or why not?

Freddie Aguilar's "Bayan Ko"

Perhaps the most important recording of "Bayan Ko" during the Marcos dictatorship was made by Filipino folk-rock musician Freddie Aguilar. Released in 1979, Aguilar said that his recording was meant to "jolt back those who were starting to forget who we really are."

Click to the next slide to listen to Aguilar's version of the song.

Freddie Aguilar, by Martine Girard. CC BY-SA-2.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Freddie Aguilar's "Bayan Ko"

"Bayan Ko" and the End of the Marcos Dictatorship

After the assassination of an opposing politician (Ninoy Aquino) in 1983, Aguilar's recording of "Bayan Ko" was played repeatedly on radio and in the streets. Aguilar even sang the song at Aquino's funeral.

From then on, the song was a mainstay at protests that ultimately overthrew the Marcos regime in 1986.

People Power Monument, photo by Daniel Y. Go. CC BY-NC-2.0, via Flickr.

Kundiman in the United States

In the United States, Filipino Americans have performed (and continue to perform) kundiman in a variety of ways (concerts and more informal settings). In the linked example, "Bayan Ko" is played as a piano arrangement.

A common way of preserving/adapting a music tradition is to arrange traditional songs for a new instrument.

Constancio de Guzman: Bayan Ko (My Country) - Piano Solo. Uploaded by Andrei Hadap - Pianist-Composer.

Leslie Damaso and Her "Bayan Ko"

Leslie Damaso is a contemporary Filipina American singer, visual artist, poet, writer and educator. Trained as an operatic singer, she now performs in a wide variety of styles, and runs the Buttonhill Music Studio in Mineral Point, Wisconsin.

Released in 2020, Damaso's "Bayan Ko" music video is a collaboration with Madison-based multi-genre combo Mr. Chair.

Bayan Ko | Leslie Damaso & Mr. Chair. Uploaded by Mr. Chair Music.

Damaso Discusses Her Relationship with Kundiman

In this interview excerpt, Damaso discusses how she started learning and performing kundimans, her views of preservation, and how she believes that kundimans symbolize both freedom and a sense of uncertainty.

Optional Activity: Compare and Contrast

What are some similarities and differences between the four versions of "Bayan Ko" that you listened to in this component (kundiman)? How did each make you feel?

Which of the terms introduced at the beginning of this component--"preservation," "sustainability," "third space" and "nostalgia"--apply to each of these three recordings?

Which of these recordings did you like the most or the least? Why?

Optional Activity: Perform "Bayan Ko"

If you are teaching this lesson in the context of a music classroom (especially choir) - consider adding "Bayan Ko" to your concert repertoire.

If not, you can still print out the lyrics or and sing along for fun during class (along with the recording)!

You could also collaborate with your school's choir teacher to create an integrated learning experience for your students.

Learning Checkpoint

- How has cultural heritage and tradition been preserved, sustained, and and transformed through music in Filipino American communities?

- How do the musical examples in this component show us that traditions are in a constant state of change?

End of Component 1: Where will you go next?

Return to Pathway homepage:

Hear Us Out! Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, Pacific Islanders, and Their Music

Preserving and Sustaining Cultural Heritage: Pinpeat

Component 2

30+ minutes

Pinpeat Musicians Rehearse, by Sojin Kim. Smithsonian Folklife Magazine.

Pinpeat: Cambodian Classical Music and Dance

Pinpeat (ពិណពាទ្យ) is the name of the classical court music that accompanies the Cambodian Royal Ballet, theatrical performances, ritual ceremonies, and community events.

Master Ho Chan Pin Peat Ensemble and Modern Apsara Company with the Long Beach Symphony, photo by Salvador Farfán. CaughtintheMoment.com.

Listening: Robam Buong Suong របាំបួងសួង

Listen to an excerpt from "Robam Buong Suong," recorded by UNESCO between 1966-1968. Familiarize yourself with the sounds of Cambodian classical music (pinpeat).

Buong Suong, courtesy of Cambodian-American Heritage, Inc.

"Robam Buong Suong" is a dance from this repertoire, traditionally performed before ritual ceremonies.

Instruments of Pinpeat

Chum Nyek Playing Pinpeat Instruments, by Robin S. Kent. Top left: Roneat thung; Bottom: Kong thom; Right: Sralai. musicofcambodia.org.

Instruments of Pinpeat

Chum Nyek Playing Pinpeat Instruments, by Robin S. Kent. Top left: Skor Thum; Bottom: Sampho; Right: Chhing. musicofcambodia.org

Transformations of Cultural Heritage: Pinpeat

In this component, you will consider how Cambodian music and dance has adapted and tranformed after the Khmer Rouge genocide (1975-1979) and relocation in the United States.

Cambodia: Royal Music, cover design by Jacques Blanpain, photos by Jacques Brunet. AUVIDIS-UNESCO.

Cultural heritage constantly changes every day as people encounter or realize new ideas as well as become inspired by other people and their cultural practices.

Historical Context: Vietnam War

Two Army soldiers watch a wave of Bell UH-1 Iroquois helicopters during the Vietnam War, ca. 1967, unknown photographer. Smithsonian Magazine.

Historical Context: Khmer Rouge

Destruction of Religious Structures by the Khmer Rouge. Courtesy of the Documentation Center of Cambodia.

Khmer Rouge Genocide

Evacuation of Khmer Refugees to Nong Chan Refugee Camp (1980), by Jean-Jacques Kurz. ICRC Digital Archives.

Cambodian Refugees

Nong Chan Refugee Camp in Thailand (1980), by Jean-Jacques Kurz. ICRC Digital Archives.

Cambodian Refugees in the United States

Cambodian American Women and Children Relax in Chicago (1990s), by Stuart Isett.

Cambodian Classical Music and Dance in the United States

In the United States, Cambodian Americans have worked to maintain and reclaim aspects of their cultural heritage after this devastating loss.

The Cambodian-American Heritage Dancers and Chum Ngek Ensemble, by Stephen Winich. Library of Congress.

Master dancer Devi Yim (in foreground) rehearses with the dancers, by Sojin Kim. Smithsonian Folklife Magazine.

The following two listening activities demonstrate how Cambodian Americans have actively worked to sustain, revitalize, and adapt their artistic practices while encountering American ideas and norms.

Cambodian Classical Music and Dance in the United States

Compare and Contrast #1: "Phleng khlom" ភ្លេងក្លុំ

Cambodian Dance Reamker, unknown photographer. Collection of F. Fleury. Public Domain {{PD-US}}, via Wikimedia Commons.

Compare and Contrast #1: "Khlom" ក្លុំ

Ngek Chum, by Robin S. Kent. Smithsonian Folkways Recordings.

Compare and Contrast # 2: Neary Chea Chuor របាំនារីជាជួរ

Listen to excerpts from two versions of "Neary Chea Chuor" (both recorded in the United States):

The second version is an adaptation and reinterpretation by Cambodian American singer-scholar Tiffany Lytle (2017):

The first version is a recording of a more traditional interpretation by the Sam-Ang Sam Ensemble recorded in the United States (1996):

Notice similarities and differences.

Robam "Neary Chea Chuor" is dance from the classical repertoire (pinpeat) that is performed both in the United States and Cambodia.

Synthesis

- In part, these changes can be understood as a response to social and community forces that inform how the community constructs their identity in a new place.

- In this component, we explored how Cambodian Americans preserve and adapt their musical practices in response to life in the United States.

- Cambodian Americans have re-contextualized their music according to trends in the United States while also maintaining traditional sounds.

Learning Checkpoint

- Why did a large number of Cambodian American refugees enter the United States in the 1970s?

- In what ways have Cambodian American community preserved, sustained, and adapted traditional artistic practices (such as pinpeat)?

- What do these adaptations and transformations tell us about the forces impacting cultures and traditions?

End of Component 2: Where will you go next?

Return to Pathway homepage:

Hear Us Out! Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, Pacific Islanders, and Their Music

Who Can (Re)interpret Cultural Heritage?

Component 3

20+ minutes

Reinterpreting Cultural Heritage

These transformations and adaptations are often a response to the surrounding cultural influences as well as how a community defines their identity.

Cultural heritage constantly changes every day as people encounter or realize new ideas as well as become inspired by other people and their cultural practices.

This component looks at three examples of how cultural heritage has been transformed by musicians, including people who are not necessarily from the original cultural community.

Case Study #1: "Concerto for Taiko and Large Ensemble"

In this composition, Jon Jang draws on jazz and the Black Liberation Movement.

Chinese American composer Jon Jang's composition, "Concerto for Taiko and Orchestra" is influenced by Black musicians, artists, and activists.

He connects jazz with taiko, a Japanese American musical tradition, with the intent of bridging experiences in the United States.

Case Study #1: "Concerto for Taiko and Large Ensemble"

Does ethnicity and identity impact who can or cannot adapt cultural heritage? Why or why not? When and how should cultural heritage be adapted?

As you listen, notice how taiko drums and jazz sounds fit together.

What do you think Jon Jang is trying to convey about Black American and Japanese American/Asian American experiences in the United States? Is he successful in conveying his message?

Case Study #2: "Four Seasons Medley"

Her music blends genre and musics from across the world together to unite people across difference.

Wu Fei, by Shervin Lainez. Smithsonian Folkways Recordings.

Wu Fei is a guzheng player, vocalist, and composer originally from Beijing, China.

Case Study #2: "Four Seasons Medley"

She and Wu Fei formed a duo and merged old-time music with Chinese folk song to connect these two disparate folk musics.

Abigail Washburn, by Shervin Lainez. Smithsonian Folkways Recordings.

Abigail Washburn is an Appalachian old-time banjo player.

She majored in Asian Studies at Colorado College, and studied abroad in China while learning Mandarin Chinese and Chinese music.

Case Study #2: "Four Seasons Medley"

What language do you hear? What do the lyrics convey to the listener?

Does having a relationship/long-term engagement with a cultural practice impact who can or cannot adapt cultural heritage? Why or why not? When and how should cultural heritage be adapted?

Listen to how Wu Fei and Abigail Washburn interact throughout the music.

Case Study #3: "La danza de Coyolxauhqui"

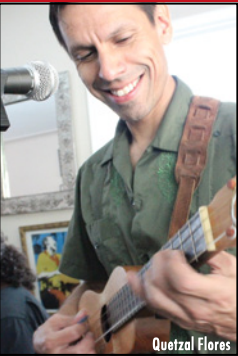

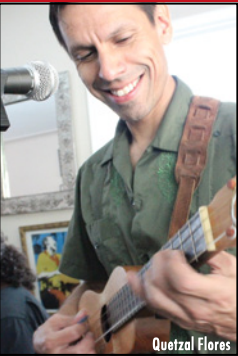

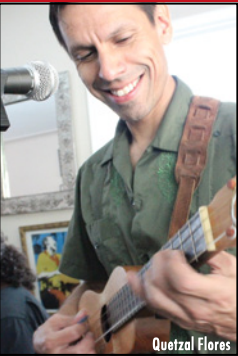

Quetzal Flores, a self-proclaimed "Chicano Artivista," is involved in the arts communities of Los Angeles: He uses his music and the arts to engage the community, open critical conversation about oppression, and work towards healing through collectivity.

Quetzal Flores. Album photos by Photos by Karen Walker Chamberlin and Daniel E. Sheehy, Smithsonian Folkways Recordings.

Case Study #3: "La danza de Coyolxauhqui"

Left: Kaz Mogi, Taiko. Courtesy of the artist. Above: Quetzal Flores, Jarana Tercera; Top Right: Tylana Enomoto, Violin, photos by Karen Walker Chamberlin and Daniel E. Sheehy, Smithsonian Folkways Recordings.

Quetzal's album The Eternal Getdown (2017) uses music to articulate the resilience of people facing discriminatory violence and oppression in the United States. It aims to give voice and power to marginalized communities.

Their song, "La danza de Coyolxauhqui," uses instruments such as violin, jarana tercena guitar, and taiko drum.

Case Study #3: La danza de Coyolxauhqui

Does this track promote healing? How?

Should intentions impact who can or cannot adapt cultural heritage? Why or why not? When and how should cultural heritage be adapted?

Through the usage of taiko, jarana tercera, and violin, does this track convey the importance of self-reflection?

Reflection: Reinterpreting Cultural Heritage

- What is different about these artists and their reinterpretations of cultural heritage? What are their goals?

- How did they transform these art forms?

- Given these artists' backgrounds and artistic intentions, do these cultural fusions make sense to you? Would you do anything differently?

Optional Creative Activity: Reinterpreting Cultural Heritage

Re-interpret it in some way: Create new music or art based on or inspired by the music or art form you have researched.

Research a piece of music, art form, or historical event. It can be from your cultural background or from another culture.

Write an artist statement describing how you adapted this musical or artistic form: what choices did you make, and what was your intention.

Learning Checkpoint

- How did the artists in this component reinterpret cultural heritage?

- What types of complicated relationships are involved when people transform cultural heritage?

- What are some of the responsibilities of non-culture bearers to the cultural community from whom they are modifying their cultural practices?

End of Component 3 and Lesson 8: Where will you go next?

Return to Pathway homepage:

Hear Us Out! Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, Pacific Islanders, and Their Music

Continue to Lesson 9:

Cultural Preservation and Adaptation: Kundiman and Pinpeat in the U.S.

Lesson 8 Media Credits

Audio courtesy of

Smithsonian Folkways Recordings

Images courtesy of

Cambodian-American Heritage, Inc.

Documentation Center of Cambodia

International Committee of the Red Cross Audiovisual Archives

Library of Congress

National Air and Space Museum

National Archives and Records Administration

National Japanese American Historical Society

National Museum of American History

National Portrait Gallery, London

musicofcambodia.org

Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center

Smithsonian Folkways Recordings

Smithsonian National Museum of Asian Art

Stuart Isett

UNESCO

© 2022 Smithsonian Institution. Personal, educational, and non-commercial uses allowed; commercial rights reserved. See Smithsonian terms of use for more information.

This project received Federal support from the Asian Pacific American Initiatives Pool, administered by the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center.

For full bibliography and media credits, see Lesson 8 landing page.