Hear Us Out! Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, Pacific Islanders, and Their Music

Lesson 9:

Cultural Preservation and Adaptation:

Chinese Opera in the U.S. and Māori Metal

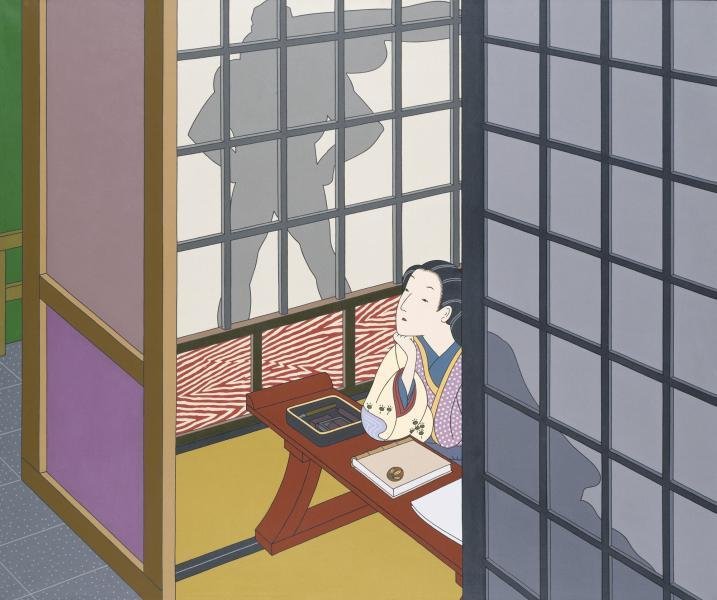

Photo Of a Cantonese Opera: Princess Cheung Ping, photo by Michelle Lee.

Lesson 9:

Cultural Preservation and Adaptation:

Chinese Opera in the U.S. and Māori Metal

What are some key theories about cultural appropriation? Which do you find useful?

How did Chinese immigrants and Māori musicians use music for cultural preservation and to address contemporary issues?

Cultural Preservation and Adaptation: Taiko and Pinpeat in the U.S.

Still from a 1924 Fox Newsreel about the opening of the Mandarin Theater in San Francisco. The opera is entitled "Emperor's Daughter."

Chinese Opera in North America

Component 1

30+ minutes

Silent footage of a Cantonese opera performance in Vancouver on February 8, 1944. The footage was shot by Vancouver filmmaker Oscar Burritt.

Chinese opera is a set of traditions that combine music, dance, martial arts, acrobatics, costumes, and makeup. It has continually evolved for over a millenium.

What is Chinese Opera?

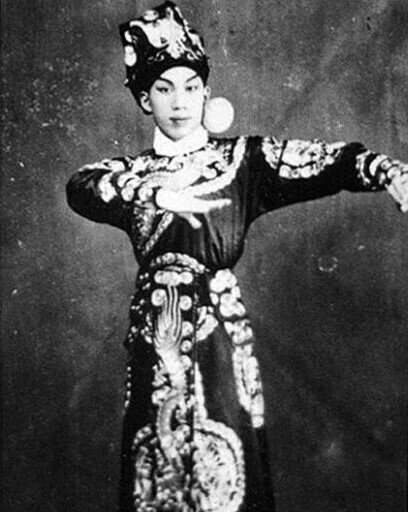

Cantonese opera star Lo Pan-Chiu (羅品超) in 1931, unknown photographer. Public Domain {{PD-US}}, via Wikimedia Commons. Lo performed in North America on several tours. After moving to the U.S. in 1988. he continued to teach and popularize Cantonese opera.

Until the mid-20th century, opera had been the most important type of entertainment for many Chinese people. Even now, Chinese popular culture makes regular references to operatic traditions.

Chinese opera also served ritual and educational functions, and contemporary events are often incorporated into performances.

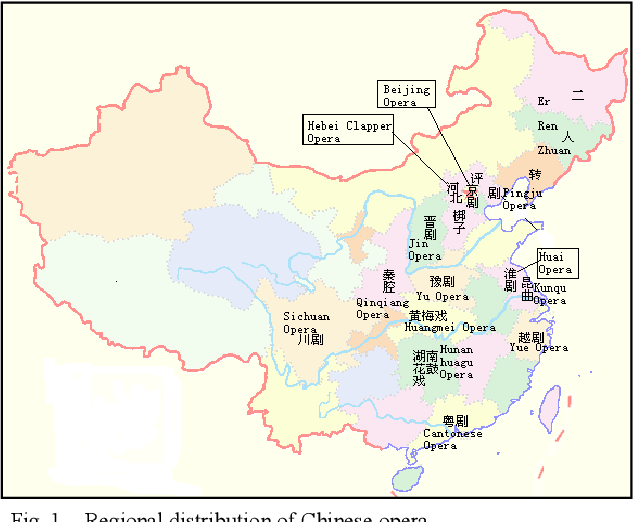

The Different Regional Traditions

There are hundreds of operatic traditions in China. The map on the right shows some of the most prominent traditions and the approximate locations where they developed.

Several of these regional traditions shared a network of aria melodies known as banqiangti.

For most of this component, we will focus on the tradition from the very south of China: Cantonese opera (粤剧).

Why Cantonese Opera?

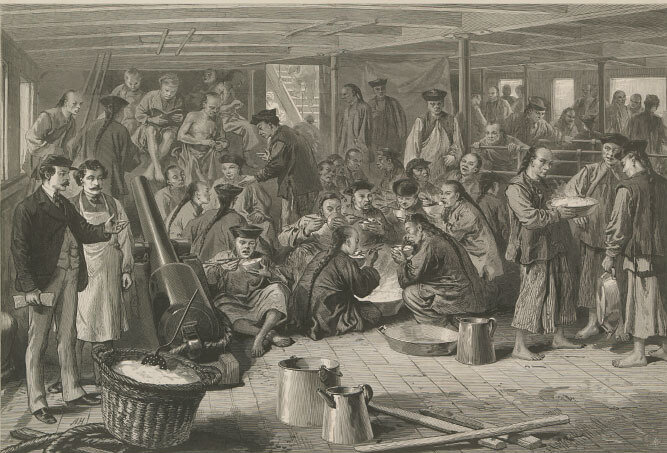

Chinese Emigration to America: Sketch on Board the Steam-Ship Alaska, Bound for San Francisco, unknown artist. Public Domain {{PD-US}}, via Hong Kong Baptist University Library Art Collections.

We focus on Cantonese opera because most Chinese immigrants from the Gold Rush to the 1960s were predominantly from the Pearl River Delta region of Guangdong province.

Cantonese opera was (and continues to be) very popular in this region.

This is due to the fact that most immigrants boarded ships in Hong Kong and Macau--cities governed respectively by Britain and Portugal during this period.

Cantonese Opera Comes to the U.S.

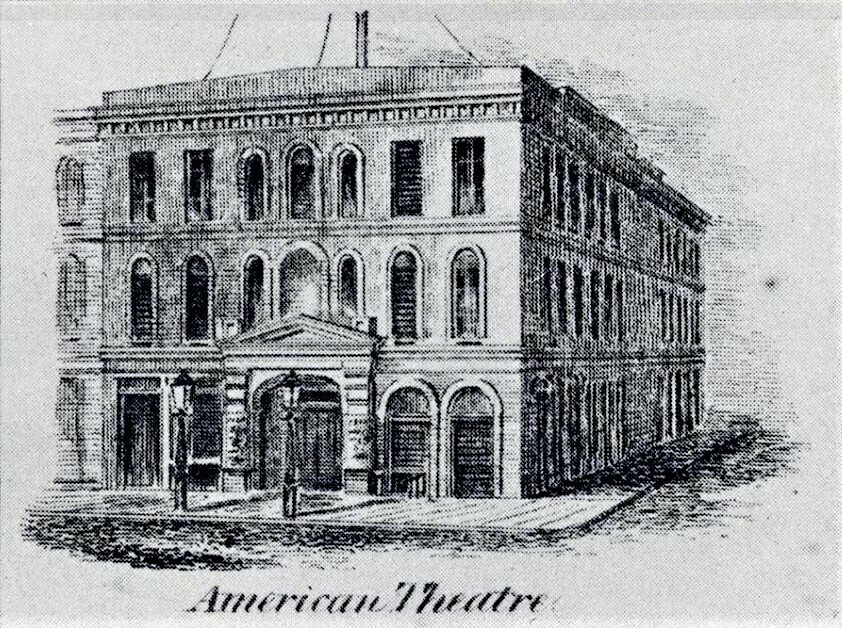

Cantonese opera took root in the U.S. soon after the Gold Rush. The first performance took place on October 18, 1852, when forty-two actors of the Hong Fook Tong troupe took the stage at the American Theater on Sansome Street in San Francisco.

Music scholar Nancy Yunhwa Rao found an article published in The San Francisco Call that lists the Chinese theater at Union Theater as the third or fourth highest-grossing theater in San Francisco from September 1867 to February 1868.

American Theatre ca. 1851, unknown artist. Public Domain {{PD-US}}, via Calisphere.

The Late 19th Century

The last quarter of the 19th century marked the first "Golden Age" of Cantonese opera in the United States. Not only were there multiple theaters in San Francisco, Chinese theaters were established in Sacramento and several small California mining towns, including Oroville, Marysville and Nevada City. Portland (Oregon) established its first Chinese theater in 1879, and New York City opened a Chinese theater in 1892.

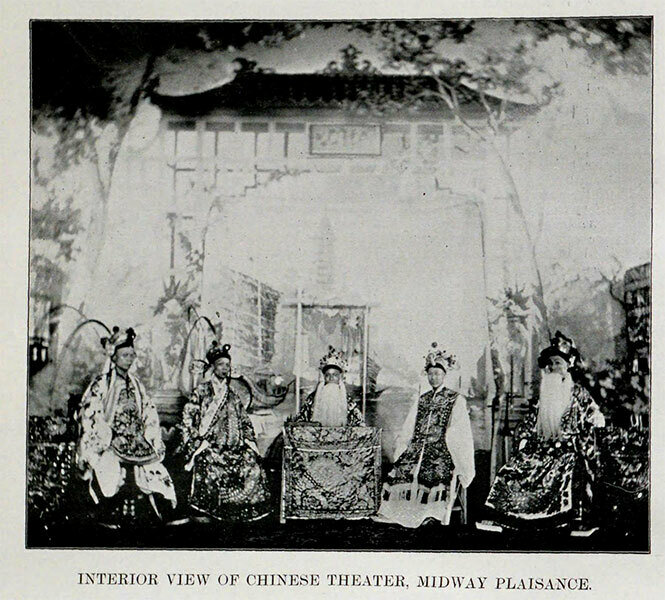

Chinese opera was featured in many World's Fairs. This photo shows the interior of the Chinese theater at the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893.

Interior View of Chinese Theatre, Midway Plaisance, unknown artist. Public Domain {{PD-US}} via Internet Archive.

The End of the First Golden Age

The Chinese Exclusion Act did not initially affect Chinese theaters and touring opera performers. However, the dwindling Chinese population after 1890 and increasingly stringent immigration policies led to the end of the first "Golden Age" of Cantonese opera in the United States.

This era officially closed when the two remaining Chinese theaters in San Francisco burned down in the aftermath of the 1906 Earthquake. Professional performances of Cantonese operas would not resume in the U.S. until the early 1920s.

Chinese Theatre in Oroville, by Charles Richard Miller. Public Domain {{PD-US}} via Meriam Library Special Collections Department, SCU, Chico.

The Return of Cantonese Opera

In 1922, Chinese American merchants successfully made a deal with the Department of Labor. This agreement allowed companies to bring in a limited number of Chinese opera singers on short-term visas.

Over the next four years, these merchants opened theaters in San Francisco, Los Angeles, Portland, Seattle, Chicago, New York and Boston, thereby ushering in the second "Golden Age" of Cantonese opera in the United States.

Stage of the Great China Theatre, by the Brooks Firm.

Some of the performers who came to perform in the U.S. were top stars. This was particularly true during the Canton-Hong Kong labor strikes in 1925-26, which severely limited opportunities for opera performers.

Performers Included Many Stars

From the mid-1920s to the 1930s, approximately 100 professional Chinese opera singers entered the U.S. each year. Many performed in several cities with Chinese theaters. Many also appeared on stages in Havana, Mexicali and various Canadian cities.

Lee Hoi-Chuen (1901-65) was a Cantonese opera performer. In 1940-41, he joined a troupe in San Francisco. During this contract, his wife Grace Ho gave birth to their son Bruce, who become a legendary martial artist and actor in the 1960s and 70s.

Lee Hoi-Chuen, unknown photographer. Public Domain {{PD-US}} via Wikimedia Commons.

The Elements of Cantonese Opera

Like other major traditions of Chinese opera, Cantonese opera include music, martial arts, acrobatics and acting.

The Flower Princess has been the most famous work in the Cantonese opera repertory for the past half century. It tells the story of two lovers who were loyal to the recently overthrown Ming Dynasty. In this finale, the two get married, and commit suicide by drinking poison so that they do not have to accept the rule of the Qing Dynasty.

Characters are based on role types, which are conveyed through costumes, makeup, as well as the performers' gestures and vocal technique.

Cantonese opera has been the dominant genre of theater in Guangdong since the 16th century. It has absorbed influences from many artistic traditions over the centuries.

Time for Reflection

Let's discuss the final scene of The Flower Princess:

- What were your initial impressions? What did you like? What did you not like?

- Were you surprised by what you heard or saw?

- Does the plot remind you of any novel/play/movie/Western opera?

- How are these characters similar to and different from East Asian characters you see in the novels/plays/movies/Western operas you read/see?

The Music of Cantonese Opera

Cantonese opera incorporates:

- Banqiangti (the network of melodies used by many Chinese opera traditions)

- Local narrative song traditions (muk'yu and naamyam)

- Other vernacular traditions

Some of the melodic instruments (bowed, plucked and wind) used in Cantonese opera. In recent decades, operatic ensembles often include a few Western instruments, such as violin and saxophone.

The stage performers are supported by melodic instruments (which plays different versions of the same melody) and percussion instruments (which sets tempos, provide directions, and accent what is happening onstage).

Focus on Naamyam

Naamyam (南音; "Southern Tone") is a Cantonese style of narrative song. The lyrics usually set a mood rather than tell a complicated story. "Sorrows on an Autumn Trip" (客途秋恨) is a famous naamyam. Here, the singer yearns for a courtesan he could not be with because of his travels.

Bai Jurong (1892-1974) was one of the Cantonese opera stars who came to the U.S. because of the 1925-26 strike. He gave only 100 performances at the Great China Theater in San Francisco. Bai was known for his relaxed singing voice and for incorporating more vernacular elements in Cantonese opera.

Bai Jurong's 1961 recording of the naamyam "Sorrows on an Autumn Trip."

Reflection and Optional Comparison

- What were your first impressions of Bai Jurong's recording of "Sorrows on an Autumn Trip"?

- How is this recording similar to and different from the finale of The Flower Princess?

For those who want an extra challenge:

- Compare Bai Jurong's recording of "Sorrows on an Autumn Trip" to Dou Wun's (starts at 1:09:53 of video on right). Dou Wun (1910-79) was a famous naamyam singer who performed mostly in restaurants, teahouses, brothels and on streets. He was not an opera performer. Which version did you like better? Why?

Optional: Learning More about Naamyam

In this video, Dr. Yu Siu Wah contrasts notions of composition and performance in Western classical music to practices in naamyam.

Based on folk and popular genres you know, how are the practices of naamyam similar and different?

The Functions of Cantonese Opera in U.S. Chinatowns

Cantonese opera served numerous functions in U.S. Chinatowns. These include:

- Entertaining the community

- Performing Rituals (operas can be offerings to deities or parts of ceremonies to bring good luck and prosperity and to ward off bad spirits)

- Teaching children about Chinese culture, language and values

- Reflecting on recent experiences and contemporary issues (this is made possible because the genre is highly flexible and includes many moments for improvisation)

Reflect on a genre of music you know. Think about the different functions it serves in the lives of listeners.

Why U.S. Chinatowns Changed Cantonese Opera

When Cantonese opera stars returned to Hong Kong and China, they brought practices they began implementing in North America. Chief among these are:

- Mixed-gender troupes (These had hitherto been considered immoral. In North America, this practice began because there simply weren't enough performers from one gender to put on good performances);

- Greater prominence given to actresses;

- More realistic and elaborate sets and backdrops (see right)

A Woman Center Stand Before An Arch Doorway, by May's Photo.

Cantonese Opera for Non-Chinese Americans

It is also important to remember that the audiences at U.S. Chinatown theaters were not all Chinese. There were tourists, journalists, friends, people in nearby neighborhoods, and other people with interest in Chinese culture.

Many non-Chinese Americans were introduced to Cantonese opera through parades. On the right, you see the elaborate Great China Theater float at the 1925 California Diamond Jubilee Celebration.

Great China Theater Float at the California Diamond Jubilee Celebration, by Hamilton Harry Dobbin.

Cantonese Opera and Non-Chinese American Artists

Composer Henry Cowell grew up near San Francisco's Chinatown, and went to Chinatown theaters. He developed a lifelong obsession with the really flexible ways Cantonese opera performers use "sliding tones." He wrote about it in theoretical works, and incorporated the technique in many works. One example is the 5th movement of Symphony No. 11.

Although many non-Chinese who came to Cantonese opera performances claimed not to have enjoyed the experience, others--including several artists--were deeply moved and inspired. A good number wrote plays and operas that demonstrate some understanding of Chinese opera. Many of these are based on problematic stereotypes or offensive tropes. Nonetheless, they represent some attempt at intercultural understanding.

Chinese Opera in the U.S. in the 21st Century

Nonetheless, Chinese operas' biggest stars can still find some performance opportunities in the U.S. There are shows organized by Chinese American arts and entertainment organizations. Major performing arts organizations, such as Kennedy Center and university-affiliated performing arts centers, also provide some opportunities.

Since the advent of television and other forms of mass entertainment, interest in live performances of Chinese opera has declined significantly, both in East Asia and among Chinese Americans.

Chinese Opera Bobblehead, by Peter Griffin. CC0, via PublicDomainPictures.

Chinese Opera Singers in Western Classical Music

Over the past few decades, some Western classical composers have incorporated Chinese opera singers into their works.

Tan Dun's The Gate (Orchestral Theatre IV) features a female Peking Opera singer, Western operatic soprano, Japanese Puppeteer

Amateur Societies

Over the past several decades, amateur societies have been the heart and soul of the Chinese opera scene in North America. One can find numerous troupes that perform Peking opera, kunqu (a tradition from the Shanghai region), Yue opera, Cantonese opera as well as many other less well-known traditions.

Some societies have highly dedicated members and put on performances with very high production values. Meanwhile, others are much more relaxed, and focus more on the social functions of music making.

Act 1 from the Vancouver Cantonese Opera's performance of Legend of the Broken Mirror in 2015.

Focus on One Ensemble: L.A. Yue Opera Troupe

Yue opera originated in the countryside southwest of Shanghai, but its modern form--as urban entertainment performed by all-women troupes--developed in Shanghai during the 1930s.

The popularity of Yue opera spread across China through performance tours and films. Scholar Jin Jiang states that it was arguably the second most popular type of Chinese opera in the 1950s-60s.

Two members of the L.A. Yue Opera Troupe perform the "Ten Barrels" scene from Smart Girl Jiujin in 2018.

Focus on One Ensemble: L.A. Yue Opera Troupe

The Los Angeles Yue Opera Troupe, founded by Jianhua "Joanna" Wang, is dedicated to bringing this tradition to audiences throughout southern California. Members believe that the troupe's performances and workshops can lead to better intercultural understanding.

In this interview, Wang and two other members discuss how the group is run, describe how they put on shows, and the challenges they face.

MAARCH LA Yue Opera Sept 3. Uploaded by Music of Asian America Research Center.

Closing Reflections

Much of this component's content is based on Nancy Yunhwa Rao's research. In her book Chinatown Opera Theater in North America, she wrote, "It does Chinese American music history a disservice to consider Cantonese opera in the 1920s as an innocuous foreign music tradition in multicultural America. Instead, this work situates American music as an active participant in the music practices of the trans-Pacific world. It thus offers a transnational perspective on the historiography of American music that has long focused on its transatlantic connection" (p. 11).

What are the strengths, weaknesses and implications of Rao's argument? If a symphony (a European genre) by a White American composer is considered American music, should Cantonese operas put on by Chinese Americans be considered American music?

Learning Checkpoint

- Why was Cantonese opera performance so important to early Chinese Americans?

- How did Cantonese opera performance in the U.S. influence Cantonese opera performance in China and Hong Kong? How did it affect non-Chinese Americans?

- Should Cantonese operas put on by Chinese Americans be considered American music?

End of Component 1: Where will you go next?

Return to Pathway homepage:

Asian Pacific Americans and Their Music

Cultural Revitalization through Popular Culture

Component 2

30 minutes

Alien Weaponry, by Piotr Kwasnik.

The Māori People

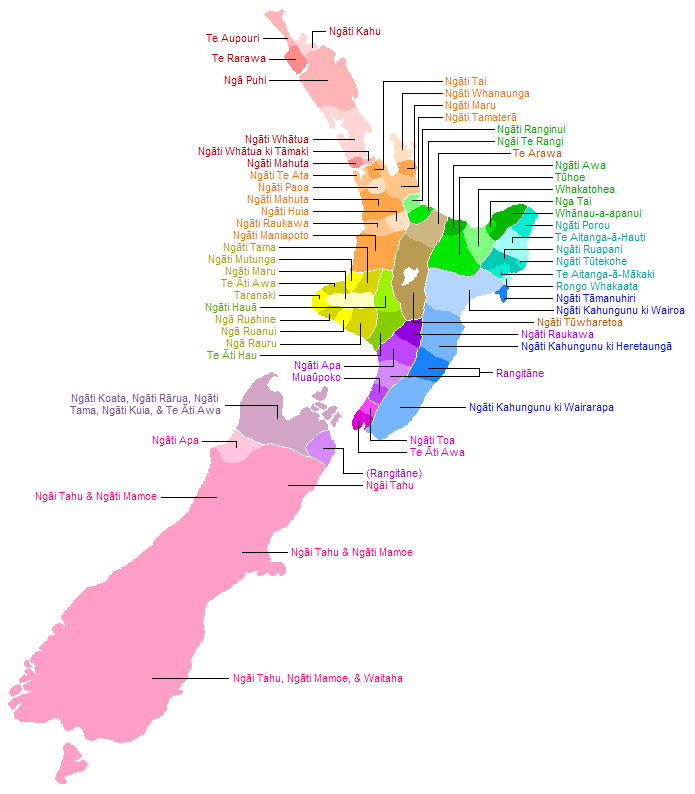

Map Showing the Location of the Iwi (Māori tribal groups) in New Zealand, by Evil Monkey.

Aotearoa

"E Ihowā Atua": Māori version of the New Zealand national anthem. Uploaded by Speak Māori.

Colonialism and Settlers

Stone Store and Mission House, Kerikeri, by russellstreet. CC BY-SA 2.0, via Flickr.

Musket Wars

ALIEN WEAPONRY - Kai Tangata (Official Video). Uploaded by Napalm Records.

Settler Colonialism Begins

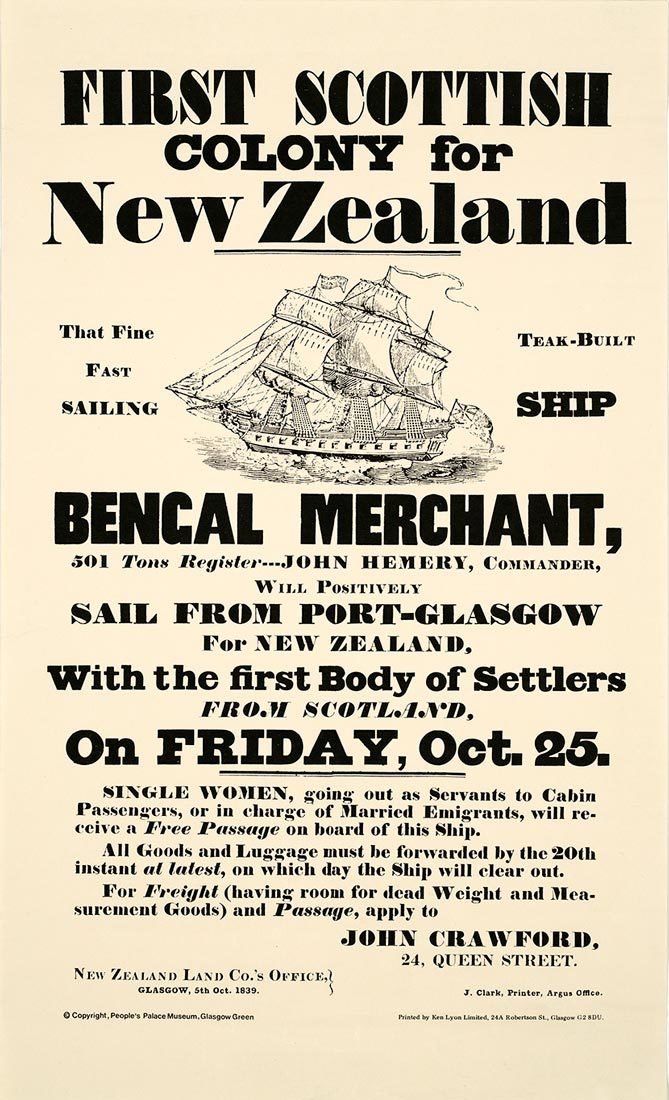

New Zealand Company poster, by J. Clark. Alexander Turnbull Library, NZ

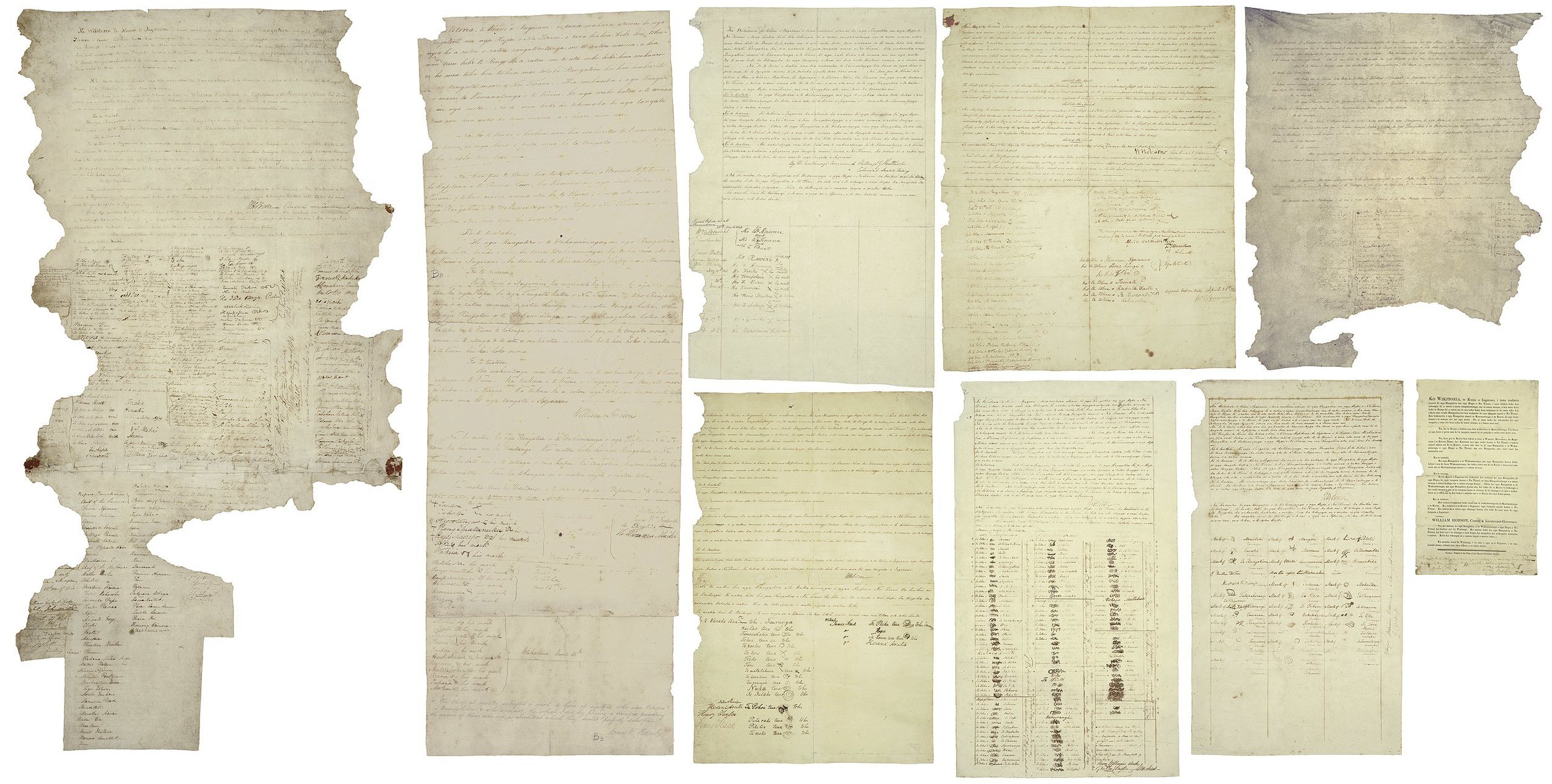

Treaty of Waitangi (1840)

Two of the nine documents that make up the Treaty of Waitangi. CC BY-SA-4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Schools and Cultural Decline

Detail of entry for 15 March 1938, Oromahoe Native School Logbook. Courtesy of University of Auckland Native Schools Project records.

The Steep Language Decline in the 20th Century

Māori Renaissance

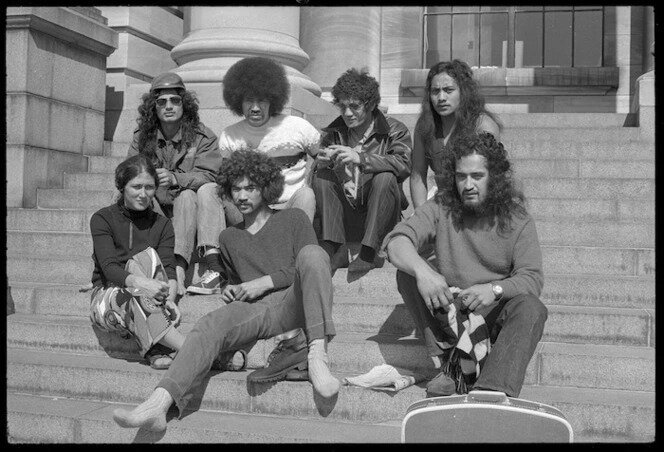

Members of the Māori activist group Ngā Tamatoa during a three-week sit-in on the Parliament Grounds in Wellington, 1972. The central theme of the sit-in was ""Maori control of all things Maori."

Group of young Māori on steps of Parliament, unknown photographer. Courtesy of the Alexander Turnbull Library, NZ.

"Poi E"

Dalvanius Prime on "Poi E"

Moana and the Moahunters

Maree Sheehan

Moment for Reflection

Let's discuss the music on the three songs you just heard for a few minutes:

- What were your initial impressions? Did you like the songs? Why/why not?

- Were you surprised by what you heard?

- Do you think songs like these can help people generate pride in their cultures?

- How might songs like these help communities that have suffered from oppression and trauma? What can't songs like these change?

Alien Weaponry

"Raupatu"

"Raupatu"

"Nobody Here"

"Nobody Here" tackles this issue. The English lyrics that frame the song focus on the relationship between social media and reality, but the band communicates the really dark lyrics in te reo Māori. These two verses talks about the Internet as an abyss, an unsafe place where your vanity reigns. However, the computer is also "my true home," as the real world has been lost.

Alien Weaponry does not just write songs about Māori history. The band also writes songs about contemporary life. One issue that many young people are concerned about is the effect of social media on their mental and physical well-being.

Moment of Reflection

Let's discuss the music on the three Alien Weaponry songs you just heard ("Kai Tangata," "Raupatu," and "Nobody Here"):

- What were your initial impressions? Did you like the songs? Why/why not?

- Were you surprised by anything you heard?

- In terms of cultural preservation and pride, are Alien Weaponry's songs more, less, or just as effective as the three songs you heard from the 1980s/1990s?

- Can songs like these spark real change?

Learning Checkpoint

- How did Aotearoa/New Zealand become a settler-colonial nation? Why is the Treaty of Waitangi such a controversial document?

- How have musicians participated in Māori Renaissance?

- What are the opportunities that music offers and what are music's limitations in terms of cultural revitalization?

End of Component 2: Where will you go next?

Return to Pathway homepage:

Asian Pacific Americans and Their Music

Cultural Appropriation

Component 3

30+ minutes

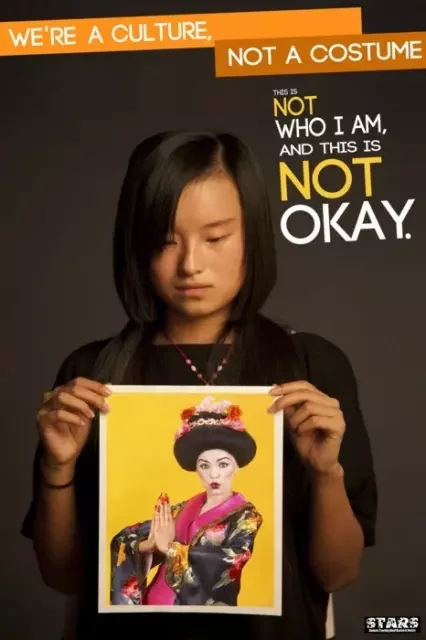

We're A Culture, Not A Costume, by Students Teaching About Racism in Society (STARS).

Building on Lesson 8

The central question of the third component of lesson 8 was, "Who may (re)interpret cultural heritage?" Here, we introduce four "cultural appropriation" theories that will allow us to answer this question with greater nuance. They are developed by a communications studies scholar, a scholar of Black feminist thought, an Indigenous artist and scholar, and a Chinese American rapper and activist.

Smithsonian's National Museum of the American Indian hosted a panel entitled "Native/American Fashion: Inspiration, Appropriation, and Cultural Identity" in 2017.

The Politics of Cultural Appropriation

Cultural appropriation is one of the most politically fraught issues in our society. People or groups who get appropriated can be seriously harmed financially and socially. Appropriation can reinforce stereotypes that lead to discrimination and violence. At the same time, cultural exchange is crucial to cultural sustainability. Moreover, appropriation is a contested term with many different definitions.

For you, what does cultural appropriation mean? What are the real-life effects of cultural appropriation? How can you ethically learn and borrow elements of another culture?

What Should We Do?

If we study a work and find it to be problematic in terms of cultural appropriation, what are some of our options?

- Choose not to program the work

- Educate and engage with our audiences about the issues raised by the work

- Perform it in a way that alleviates some of these problems

- Use the work as inspiration for new creations that are less problematic

There are many reasons to include a work in a concert, event or course. Cultural appropriation should be a consideration, but it's not the only one.

Richard Rogers

Rogers is one of the most cited scholars of cultural appropriation. He defines the term as the “active ‘making one’s own’ of another culture’s elements.”

Why many are not satisfied with his definition?

- It differs from general parlance, and doesn’t emphasize exploitation.

- Classifying the type of appropriation based solely on the identity of the appropriater is insufficient.

Richard Rogers, unknown photographer.

Brittany Cooper

Cooper differentiates between code-switching and cultural appropriation:

- “Code-switching is a tool for navigating a world hostile to Blackness and all things non-white. It allows one to move at will through all kinds of communities with as minimal damage as possible.”

- “Appropriation is taking something that doesn’t belong to you and wasn’t made for you, that is not endemic to your experience, that is not necessary for your survival and using it to sound cool and make money.”

Brittany Cooper, photo by Ryan Lash.

Dylan Robinson

Robinson outlines three major barriers to serious discussions about cultural appropriation:

- Belief in the universality of the Western legal framework for intellectual property;

- Widespread faith, particularly in academia, that knowledge should be widely shared;

- Widely held idea that the “aesthetic” world is somehow separate from everyday life.

jason chu

jason chu argues that artists who wants to ethically borrow from another culture needs to build authentic relationships with that culture. He argues that this is a four-stage process:

- Appropriation

- Appreciation

- Apprenticeship

- Authenticity

Rapper and activist jason chu speaks at the 2019 Philadelphia Asian American Film Festival. In the first 7 minutes of this video, chu sets up the cultural appropriation question. He begins to detail the four-stage process at 7:03.

Case Study #1: Madama Butterfly

Italian composer Giacomo Puccini (1858-1924) composed Madama Butterfly during the first decade of the 20th century. The opera tells the story of Cio-Cio-San, a Japanese teenager who marries an American naval officer stationed in Nagasaki named Pinkerton.

Pinkerton does not take this Japanese marriage seriously. He returns to the U.S., and marries another woman. Cio-Cio-San believes that Pinkerton would return to her (see video). When he showed up with his American wife, Cio-Cio-San commits suicide.

"Un bel di" is the most famous aria (song) in this opera. Here, Butterfly imagines Pinkerton arriving on a ship on "one fine day" ("un bel di"), and walking up to hill to return to her.

Why is this opera considered problematic?

- It portrays a world that accepts the sexually trafficking of teenage girls.

- The opera presents the stereotype of the submissive, sexualized Asian woman--a stereotype that continues to harm Asian / Asian American women today

- Puccini and his collaborators did not have in-depth knowledge of Japanese culture. Puccini in fact uses both Japanese and Chinese melodies in this opera, thereby conflating different Asian cultures.

- The opera is often performed in yellowface, with non-Asian singers portraying Asian characters

Case Study #1: Madama Butterfly

Discussion:

- Are the four theories discussed in this component useful for talking about Puccini's Madama Butterfly? How so/why not?

- Do you find Madama Butterfly to be problematic? Why/why not?

- If you think that Madama Butterfly is problematic in terms of cultural appropriation, do you think it should be performed? Do you think there are ways to alleviate these problems?

Case Study #1: Madama Butterfly

In Spring 2022, the Boston Lyric Opera hosted a series of conversations about Madama Butterfly. This panel focused on orientalism and cultural appropriation.

Case Study #2: "Sepuluh Jari"

Gareth Farr, photo by Schwede66.

Gareth Farr (b. 1968) is a composer and percussionist from New Zealand. He heard a gamelan--a percussion-based musical ensemble from Indonesia--in 1988, and immediately fell in love with these traditions.

There are numerous gamelan traditions in Indonesia. Farr studied the traditions from the island of Bali extensively, and has borrowed heavily from Balinese gamelan practices in many of his compositions. In 1996--still fairly early in his immersion of Balinese gamelan traditions--Farr wrote a work for solo piano called "Sepuluh Jari" ("Ten Fingers" in Indonesian).

"Sepuluh Jari" borrows numerous Balinese musical elements. Let's focus on the section starting at 4:41:

- Eight-beat gilak gong cycle (in the bass)

- Repeated note imitates the kajar, the instrument that keeps the beat

- Simple pokok (melody outline) using the notes available on gong kebyar instruments in the mid-range

- 5:22: Nyog Cag elaboration of pokok (creates flowing line)

- 5:46: Angsel rhythmic articulation

- 5:48: Kotekan Empat (four-note) elaboration of melody

Case Study #2: "Sepuluh Jari"

I point these elements out to demonstrate the extent of the borrowing. I do not expect you to know the Balinese terms.

From a recently-unearthed letter, apparently in the hand of of J.S. Bach:

“And here it is, my recently completed toccata, Sepuluh Jari – it means “ten fingers” in the native language here on the island of Bali.

I'm forever grateful to you for persuading me to take leave from my position as church organist and spend a year in the Hindu lands of India and Bali. I have found the rhythms and scales of the music here so inspirational that I could not stop them from creeping into this piece.

You must forgive me, though, if it gets a little crazy at times; a strange potion offered me from a coconut shell may be to blame – it made me feel quite queer.”

The rest of the letter is illegible.

Case Study #2: "Sepuluh Jari"

Farr also writes the following preface to the score:

Case Study #2: "Sepuluh Jari"

The preface is obviously a joke, but it also pays homage to the many 20th-century composers, such as Colin McPhee and Benjamin Britten, who associated the sound of gamelan with queerness in some way. This is a rather problematic tradition in terms of cultural appropriation.

Discussion:

- Are the four theories discussed in this component useful for talking about Farr's Sepuluh Jari? How so/why not?

- If you are to give an introduction to Sepuluh Jari in a class or concert, how might you present the piece?

Case Study #3: "The Year's Midnight"

Born in Chicago, Reena Esmail (b. 1983) is the daughter of Indian immigrants. She did not grow up with Indian classical music.

Reena Esmail.

In the Western classical music industry, BIPoC composers are often expected to know their ethnic musical traditions, and to incorporate elements of them in their music. So, it is not surprising that Esmail had several teachers, colleagues and audience members who asked if she wanted to incorporate Indian classical music in her works.

Many of Esmail's works since the 2010s are based on Hindustani (north Indian) melodic frameworks called ragas or raags. Each raag has certain symbolic associations (e.g., a mood, season, time of day, etc.).

Although these questions are based on unfair expectations of BIPoC composers, they did pique Esmail's interest. She took a course on Indian classical music when she was a graduate student at Yale University, and fell in love with it. She then spent a year (2011-12) studying intensively in India, and has continued to learn more about this tradition.

Case Study #3: "The Year's Midnight"

In this video, Reena Esmail discusses her Catholic upbringing and her composition process for A Winter Breviary (2021).

Discussion:

- Are the four theories discussed in this component useful for talking about "The Year's Midnight"? How so/why not?

- If you give an introduction to "The Year's Midnight" in a class or concert, how might you present the piece?

The influence of Indian classical music is very audible in many of Esmail's work. However, this influence is very subtle in A Winter Breviary. The second carol from this set, "The Year's Midnight," is based on the raag Malkaus, which is to be sung in the small hours of the morning and has a soothing or intoxicating effect.

Case Study #3: "The Year's Midnight"

Learning Checkpoint

- What are four theories you might use to discuss cultural appropriation?

- If you believe that a work you want to teach or program participates in cultural appropriation, what can you do?

End of Component 3 and Lesson 8: Where will you go next?

Return to Pathway homepage:

Asian Pacific Americans and Their Music

Continue to Lesson 9:

Cultural Adaptation:

Lesson 8 Media Credits

Audio courtesy of

Smithsonian Folkways Recordings

Images courtesy of

Cambodian-American Heritage, Inc.

Documentation Center of Cambodia

International Committee of the Red Cross Audiovisual Archives

Library of Congress

National Air and Space Museum

National Archives and Records Administration

National Japanese American Historical Society

National Museum of American History

National Portrait Gallery, London

musicofcambodia.org

Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center

Smithsonian Folkways Recordings

Smithsonian National Museum of Asian Art

Stuart Isett

UNESCO

© 2022 Smithsonian Institution. Personal, educational, and non-commercial uses allowed; commercial rights reserved. See Smithsonian terms of use for more information.

This project received Federal support from the Asian Pacific American Initiatives Pool, administered by the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center.

For full bibliography and media credits, see Lesson 8 landing page.