Lesson 2:

The World of Asian American Experiences through 1965

Hear Us Out! Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, Pacific Islanders, and Their Music

What factors shaped the patterns of Asian migration to the U.S.?

The Farm, by Kenjiro Nomura. Smithsonian American Art Museum.

What types of communities and music cultures did these (im)migrants create?

Lesson 2:

The World of Asian American Experiences through 1965

The World of Asian American Experiences through 1965

CREATIVE CONNECTIONS

30+ MIN

20+ MIN

15+ MIN

HISTORY & CULTURE

MUSIC MAKING

Patterns of Asian Migration to the United States

Component 1

30+ minutes

Graduation Ceremony for First-Generation Immigrants of the First Americanization Class Conducted in Japanese, San Francisco, California, by Bob Laing. CC BY-NC-SA 3.0, via Densho Encyclopedia.

Review from Lesson #1: AA & NHPI Experiences

Indigenous vs. Settler?

Indigenous Peoples: Ethnic groups that are native to a place which has been colonized

Are Pacific Islanders "Indigenous Peoples" or "Settlers"?

Are Asian Americans "Indigenous Peoples" or "Settlers"?

Settlers (from an Indigenous point of view): People or descendants of people who move to lands that have been dispossessed from Indigenous People

What is Colonialism? Some Definitions

Colonials: A member of the dominant group under colonialism

Colonized: A member of a subjugated group under colonialism

Colonialism: The practice of a group of migrants subjugating other groups, including the original inhabitants of a place

Indigenous: A member of a subjugated group that is considered "original inhabitants" under colonialism

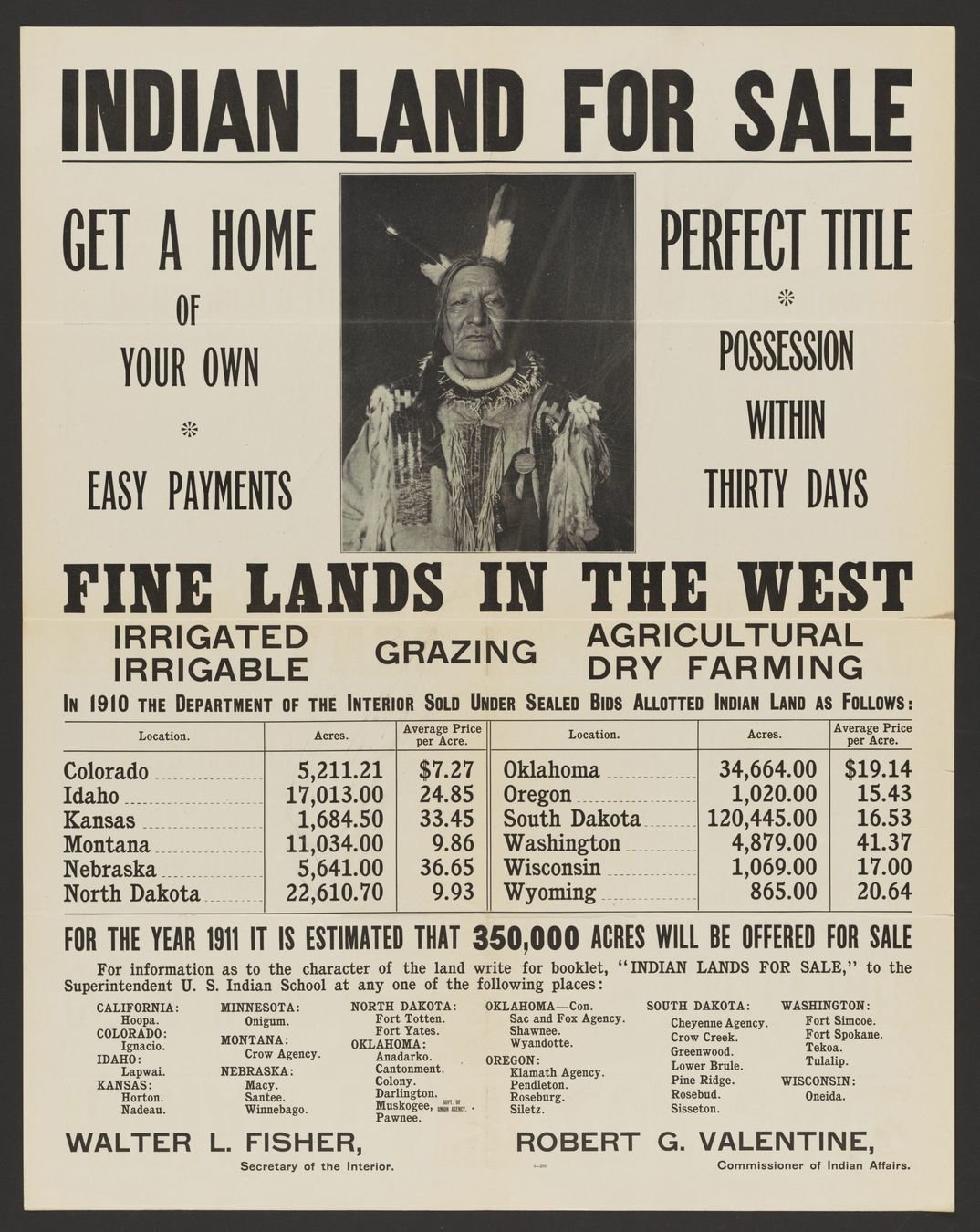

What is Settler Colonization?

Settler Colonization: A distinct type of colonialism in which the dominant group seeks to replace indigenous populations through land dispossession, the encouragement of internal/external migration, and even genocide.

Settler: A member of a non-Indigenous group under colonialism. A settler may or may not be a member of the dominant group.

Broadside Advertisement for US Dept. of the Interior Land Sale in 1911, Library of Congress.

Pacific Islands and Colonialism

Over the past two centuries, almost all inhabited islands have had significant histories of colonialism.

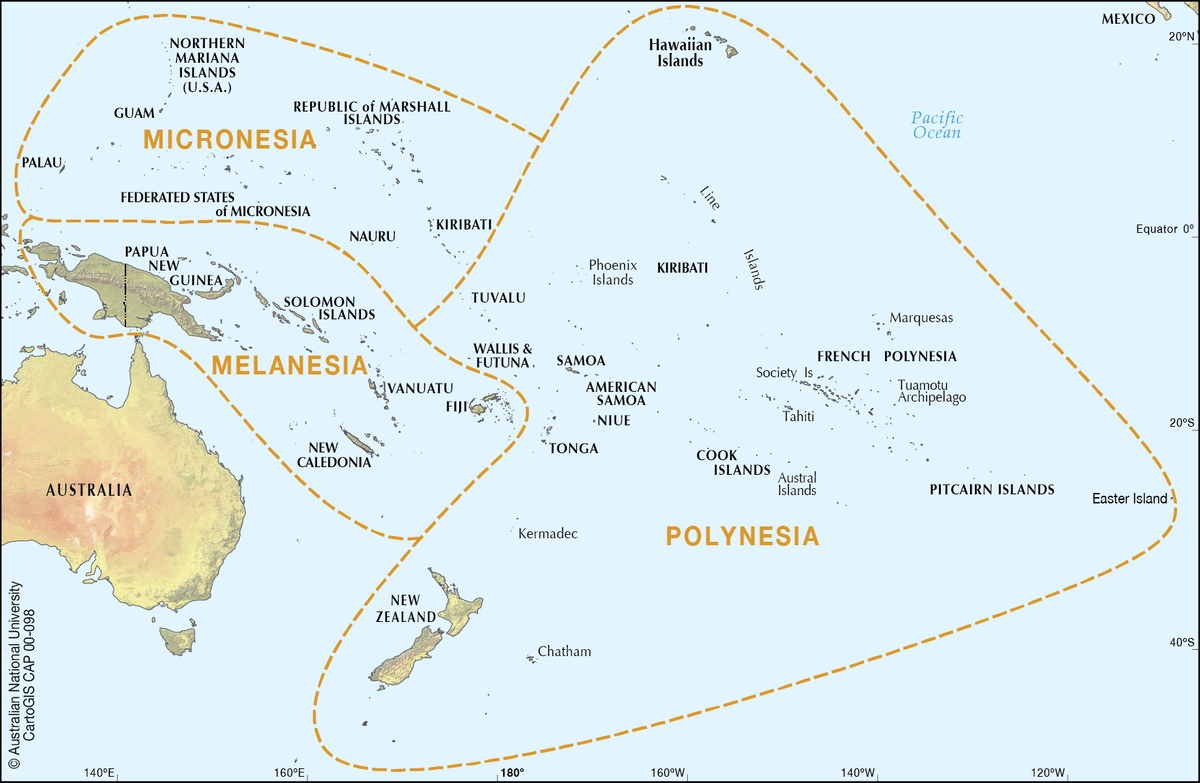

The Pacific Islands are generally divided into three cultural regions: Micronesia, Melanesia, and Polynesia.

Subregions of Oceania. CC BY SA 4.0, via CartoGIS Services, Australian National University College of Asia and the Pacific.

Native Hawaiians, Pacific Islanders, and Asian Americans

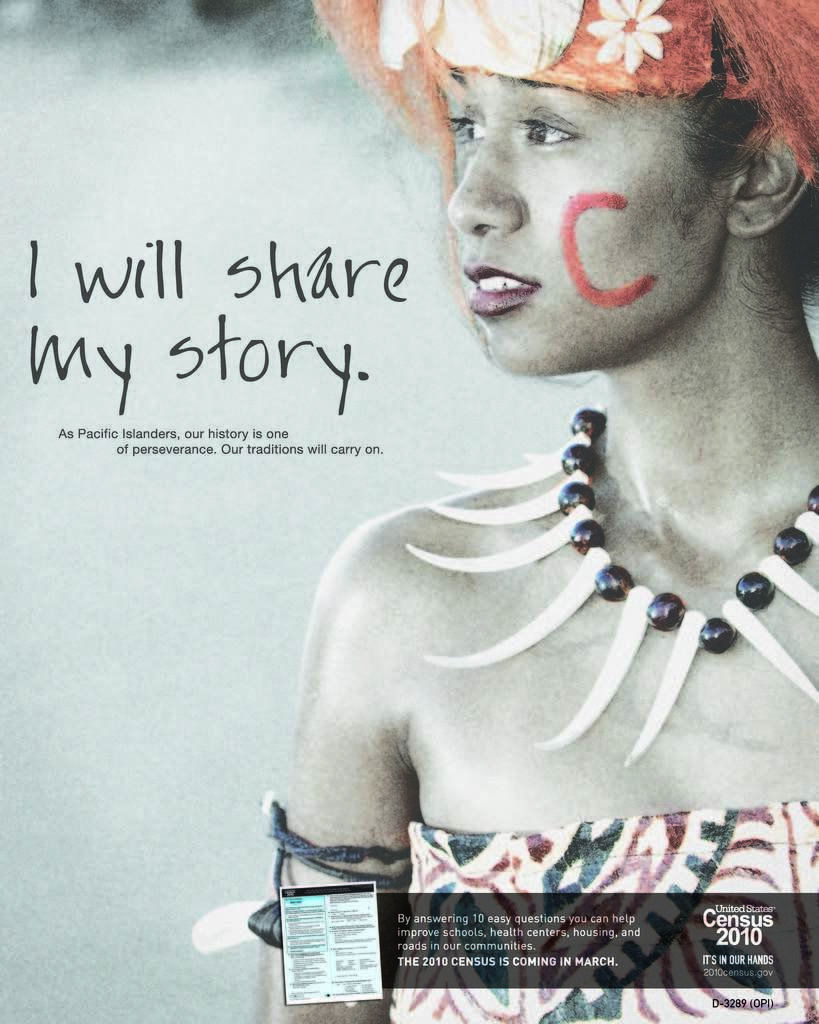

Their concerns, especially on such issues as land rights, Indigenous sovereignty and law reform, often differ from those of Asian Americans. These issues demonstrate the limits of the APA coalition.

Hawai'ians, Samoans, Chamarros (from Mariana Islands including Guam) and other Pacific Islanders are Indigenous people.

Pacific Islander Awareness Poster, by the United States Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census. National Archives, Public domain {{PD-USGov}}.

Choose Your Path

The remainder of this lesson focuses only on the experiences of Asian Americans.

To learn more about Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander experiences (NHPI), please proceed to Lesson 4.

Key Issues in Asian Migration to the United States

-

Push and Pull Factors

- Push: Factors that led you to leave where you were living

- Pull: Factors that led you to settle in a new place

- Government Policies (U.S. & Abroad)

- Labor Needs of U.S. Businesses

- Family Decisions

Voluntary vs. Involuntary Migration

The majority of Asian immigrants to the United States came by choice. People that did not come voluntarily (or at least not completely voluntarily) include:

- Many refugees (did not leave by choice; often had little choice about where they resettle);

- Transnational adoptees;

- Victims of human trafficking.

Push and Pull Factors for Those with Choice

Common Push Factors

-

War or unrest

-

Religious or political persecution or oppression

-

Lack of economic opportunities

-

Lack of educational opportunities

-

Environmental disasters

Common Pull Factors

-

Safety and political stability

-

Ability to safely practice religion or certain ways of life

-

Economic opportunities

-

Educational oppotunities

-

Better quality of life

Before 1875, the U.S. had essentially open borders.

The Massacre of the Chinese at Rock Springs, Wyoming in 1885. Drawing by T. de Thulstrup, PD via Wikimedia Commons.

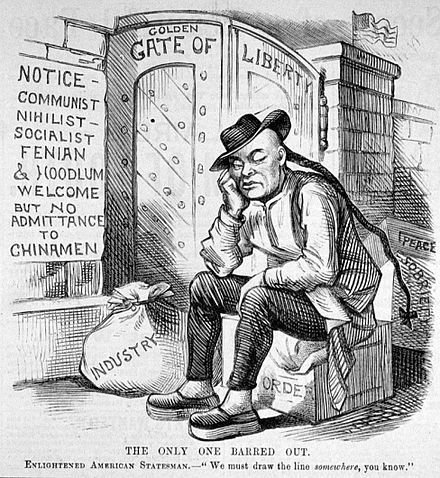

Restrictive immigration laws were created largely in response to anti-Asian sentiment and violence.

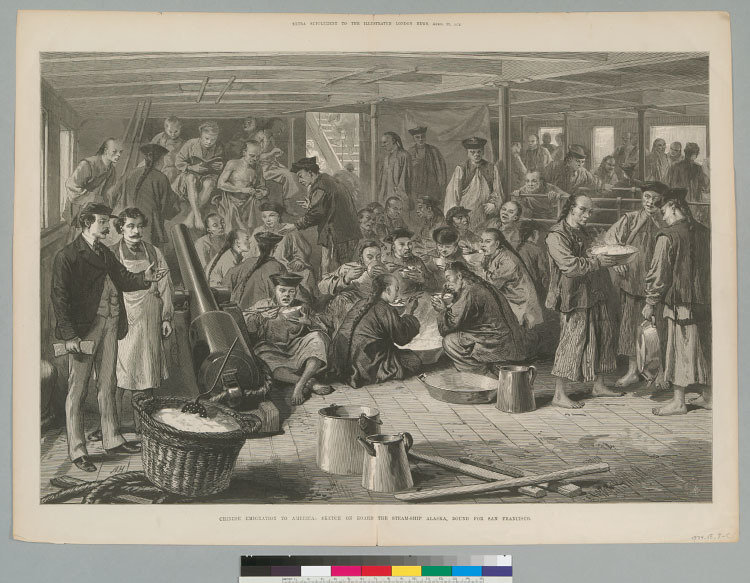

Understanding Patterns of Migration

Understanding Patterns of Migration

Asian migration patterns were determined largely by changing U.S. government policies.

Chinese Emigration to America: Sketch On-board the Steam-Ship Alaska, Bound for San Francisco. Online Archive of California.

Key determinants of these policies:

- The labor needs of businesses

- The belief that immigration depresses wages for White workers

- U.S. foreign policies

- Changing ideas about race and racism

Six Overlapping Periods of Migration

These periods are overlapping because many immigration laws applied to some Asian ethnicities/nationalities, but not others.

Before 1850: Early Settlers

Before 1850, a small number of Asians settled in the Americas to facilitate international trade, to escape from poor conditions and treatment on ships, or for other (often dehumanizing) reasons.

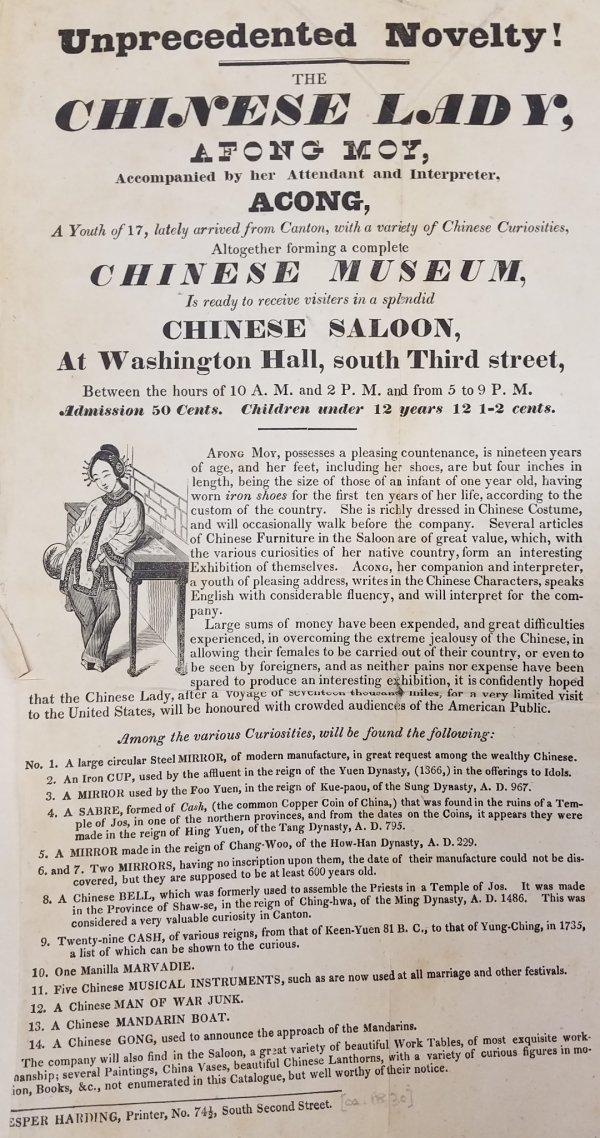

Afong Moy, considered the first Chinese woman to settle in the U.S., was brought to New York in 1834 as a marketing strategy. The Carne Brothers believed that exhibiting a Chinese woman would help them sell Chinese goods.

The Chinese Lady, Afong Moy, by Jesper Harding. The Library Company of Philadelphia.

Artistic Connection: The Chinese Lady

Lloyd Suh (b. 1975) wrote a play about Afong Moy. Entitled The Chinese Lady, it explores tensions between her desires to please her audiences through performing what they expect, and to be true to herself.

In this clip, Suh discusses the questions he was trying to raise through this play.

Code-Switching

One topic that The Chinese Lady explores is code-switching. Code-switching involves adjusting one’s behavior, speech and appearance to make others more comfortable in order to come across as less threatening, to get fair treatment, and to fit in better.

Do you code-switch? If so, under what circumstances? If not, why haven't you had to?

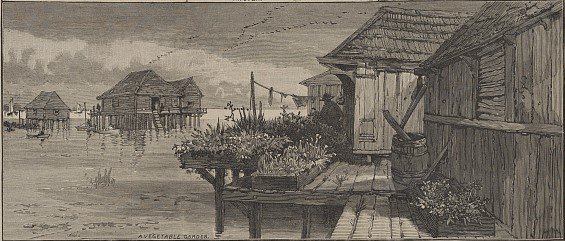

Saint Malo, Lousiana . . .

. . . provides another example of early Asian American settlers (before 1850). Saint Malo was a small fishing village established by Filipinos who escaped Spanish boats in the early- to mid-19th century. The village was unfortunately destroyed by a hurricane in 1915.

Bits of Saint Malo Scenery, by Charles Graham based off sketches by J. O. Davidson, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

1850-1934: From the Gold Rush to the Height of Exclusion

Large numbers of Asians started coming to the continental United States during the California Gold Rush (approximately 1850). Many worked on farms or railroads.

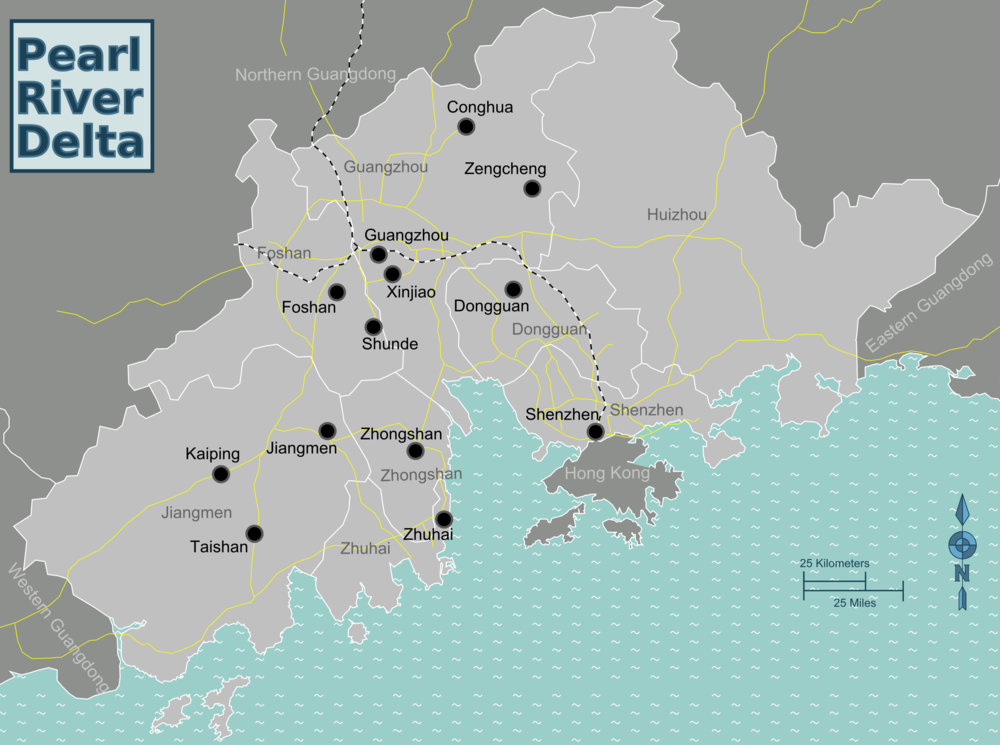

During this period, the earliest migrants were mostly from villages near Guangzhou, China (see map on right).

Map of Pearl River Delta, uploaded by user ClausHansen. CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikitravel.org.

Artistic Connection: "Ku Li"

Listen to the linked track:

What does Dawen Wang's "Ku Li" say about the lives of Chinese railroad workers and their dreams? How does it portray the racism and other challenges they faced?

Railroad workers who completed the dangerous work of blasting tunnels and laying tracks through the mountains in the North American West have inspired works by many musicians.

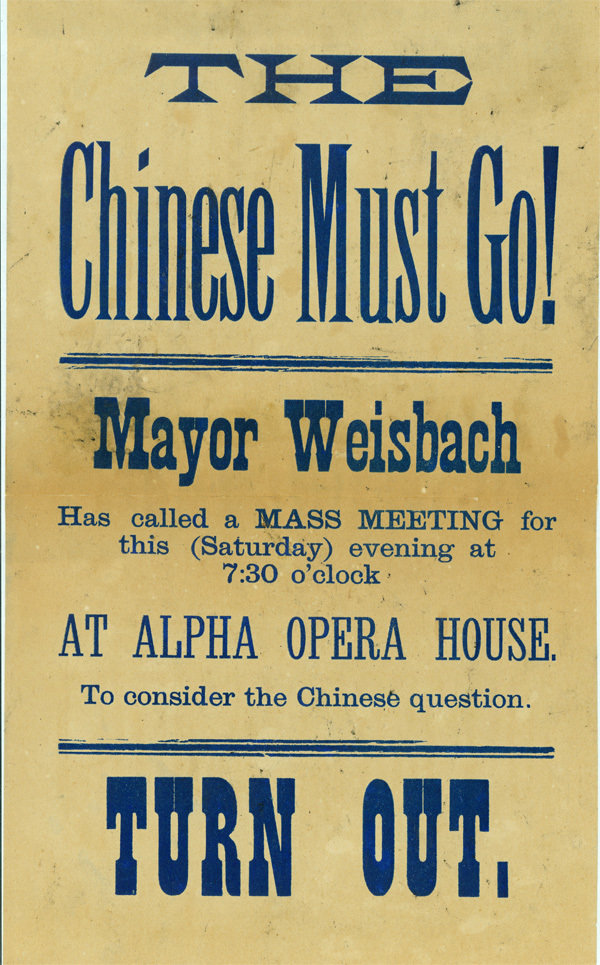

The First Immigration Laws

Because the first ethnic group of Asians to migrate to the U.S. Mainland in large numbers was from China, the first immigration laws targeted Chinese migrants:

- 1875 Page Act: Effectively barred the immigration of Chinese women

- 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act: barred immigration of Chinese laborers

Mayor Weisbach Poster in Tacoma, Washington in 1885, unknown author. PD via Wikimedia Commons.

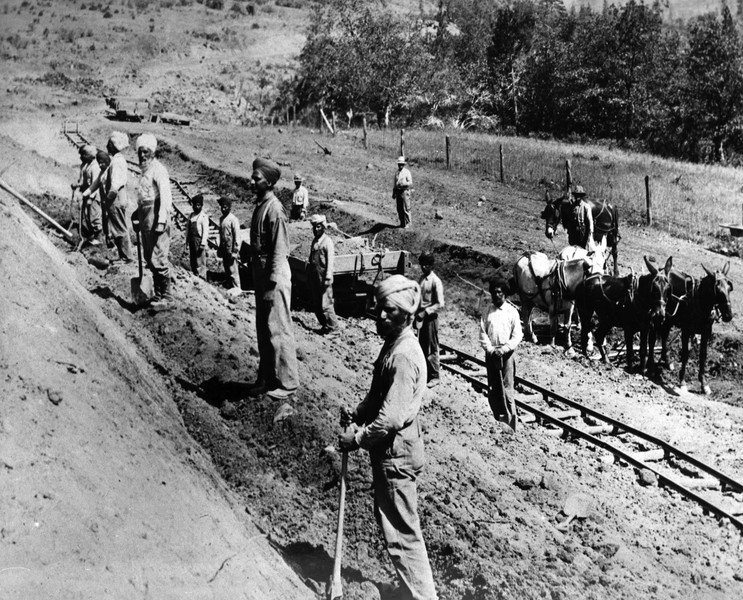

Sikh Railroad Vorkers in Oregon, c. 1909, unknown artist. UC Davis Library Digital Collections.

After the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act (1882) . . . significant numbers of laborers from other parts of Asia (such as Japan, Korea, South Asia, and the Philippines) started coming to the United States.

Most also worked on farms, railroads and canneries, but many worked in other professions, such as small business owners and cab drivers.

What happened next?

With Chinese laborers barred, merchants began to recruit workers from Japan, which led to the rise of anti-Japanese sentiment.

Picture Brides Being Processed After Arriving at Angel Island, California, c. 1910, Courtesy of California State Parks. CC BY-NC-SA 3.0, via Densho Encyclopedia.

The 1907 Gentlemen's Agreement barred the migration of Japanese laborers to the U.S., but spurred the migration of "picture brides," which allowed Japanese migrants to form families in the U.S.

1875-1943: The Exclusion Era

In the mid-19th century, anti-Asian sentiments were fueled by:

- Racist reports by missionaries, diplomats and others who traveled to Asia

- Fear of White working classes who felt that Asian migrants were taking their jobs and lowering their wages

- Newspapers and magazines that profited from spreading the "yellow peril" narrative

The Only One Barred Out Enlightened American Statesman, Library of Congress.

Exclusion Era: Anti-Asian Sentiments

Exclusion Era: Picture Brides

Picture brides were Japanese women who married Japanese immigrants in the United States based only upon the exchange of photographs and the recommendations of matchmakers.

Artistic Connection: American Postcards: Picture Brides

Listen to Takuma Itoh's quartet American Postcards: Picture Brides, which pays tribute to these women:

For you, how does Itoh's music affect the stories of the picture brides as told in the slideshow?

What do you associate the ukulele with?

What types of atmospheres and emotions does the ukuleles create in this work?

In this video, composer Takuma Itoh discusses what he was trying to accomplish when he wrote American Postcards: Picture Brides:

Optional Video About American Postcards: Picture Brides

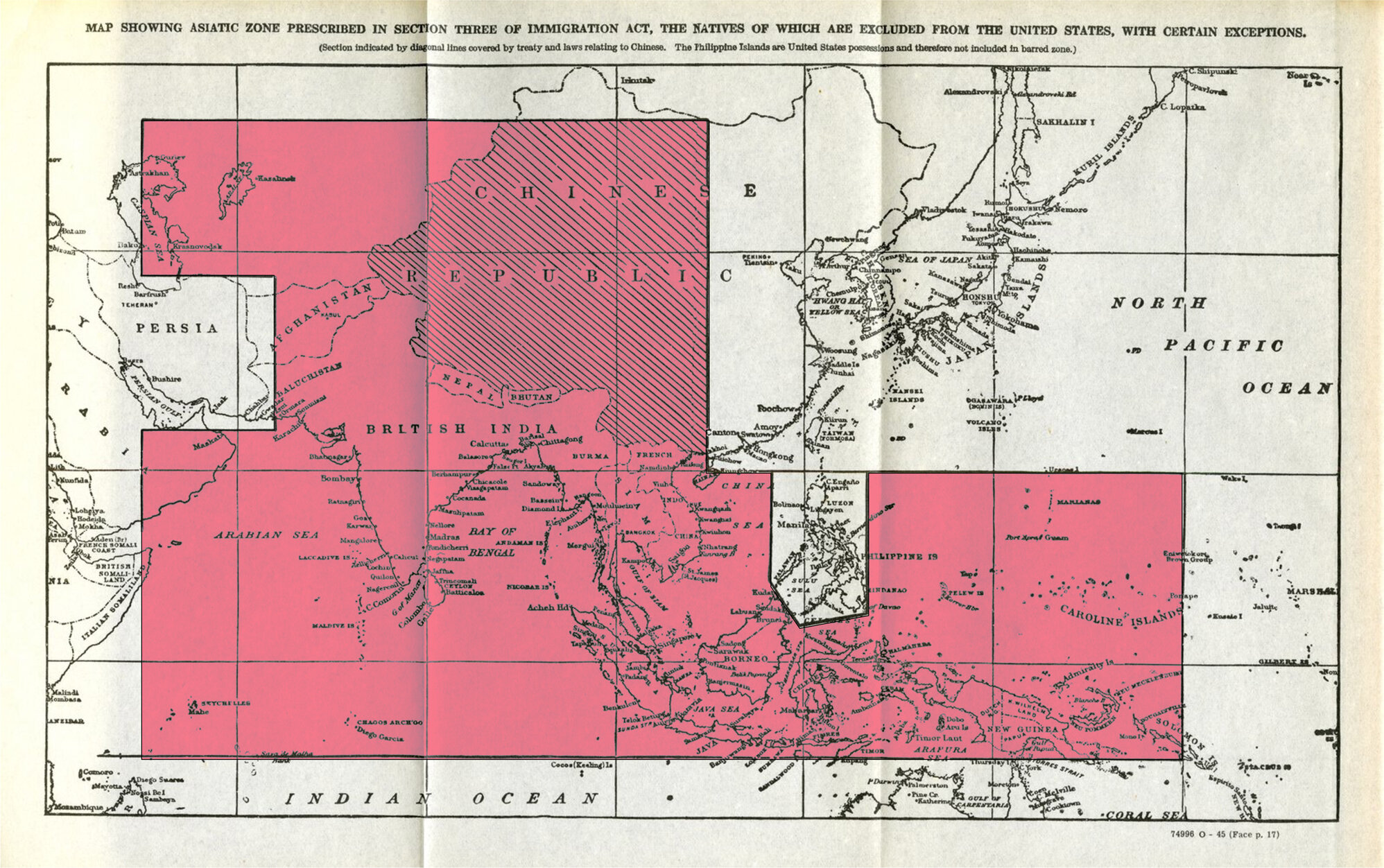

With Chinese and Japanese laborers barred, U.S. businesses began recruiting South Asians and Filipinos.

Map Showing Asiatic Zone, U.S. Congress. Courtesy of SAADA.

This led to adoption of the Asiatic Barred Zone (right), which barred South Asians and Middle Easterners from coming to the U.S.

Exclusion Era: The Asiatic Barred Zone

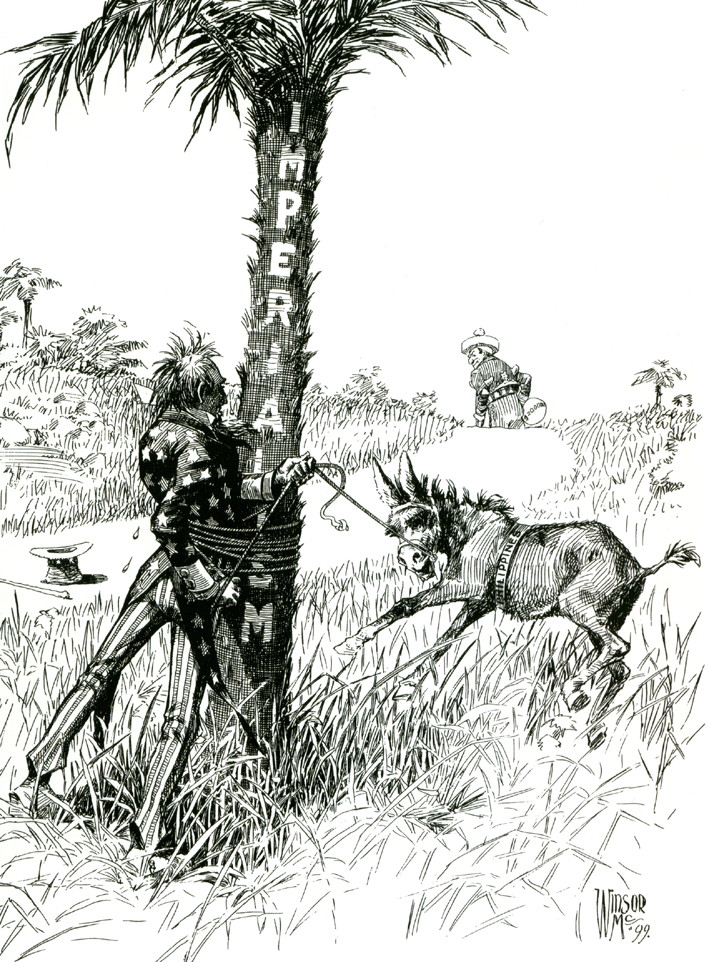

After the passage of the Immigration Acts of 1917 and 1924, Filipinos became the only Asians who were legally allowed to migrate to the U.S.

1899 Political Cartoon, by Winsor McCay. PD, via Wikimedia Commons.

Exclusion Era: Immigration Acts of 1917 and 1924

This is because the Philippines became a U.S. colony in 1898, and Filipinos automatically became US nationals (but not US citizens).

In exchange for granting the Philippines independence in 10 years, the Act reclassified Filipinos as aliens with an annual immigration quota of 50.

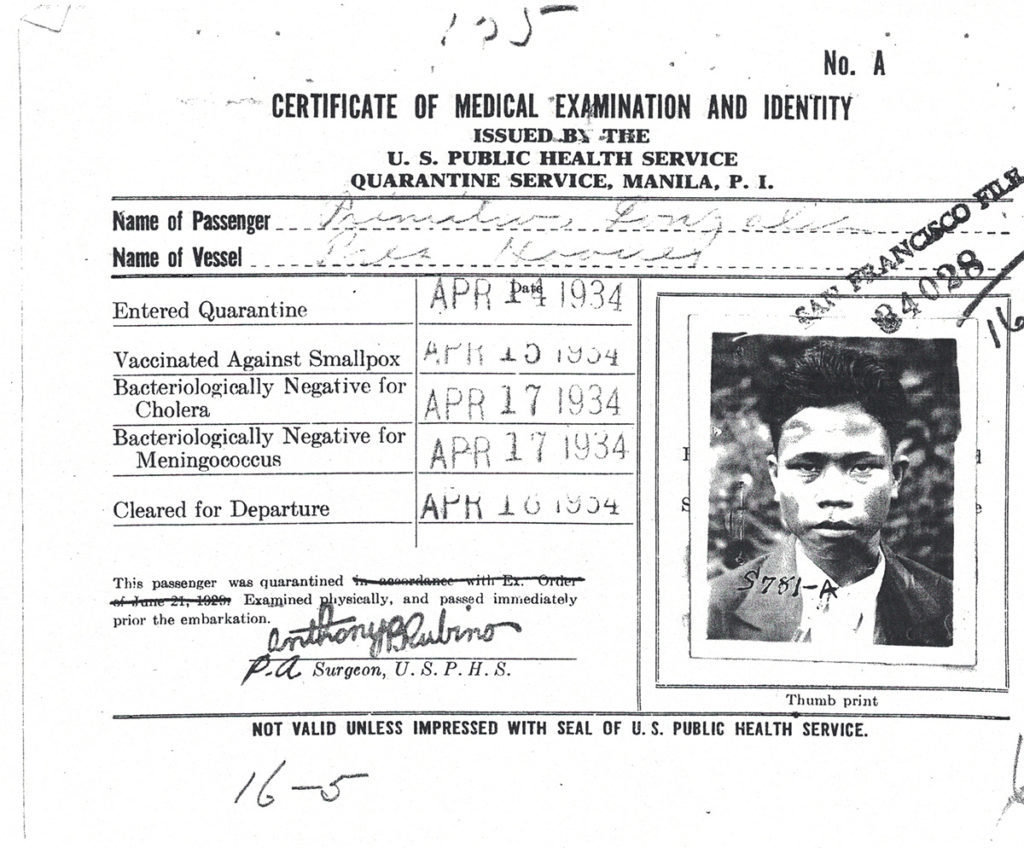

Primitivo Gonzales left the Philippines as a U.S. National on April 18, 1934. Courtesy of the National Archives, San Bruno

Exclusion Era: Tydings-McDuffie Act

In 1934, Asian Exclusion was extended one further time when Congress passed the Tydings-McDuffie Act.

Exclusion Era: 1906 San Francisco Earthquake

As the previous slide shows, immigration laws that are seen as unfair lead to undocumented immigration.

Aerial View of San Francisco Five Weeks after the 1906 Earthquake. Courtesy of the United States Geographical Survey.

For Asians in the Exclusion Era, their biggest opportunity came when the 1906 San Francisco Earthquake destroyed many government records.

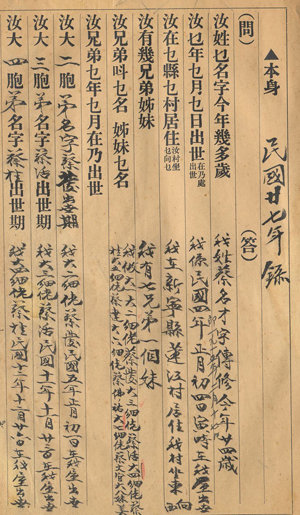

Many Chinese immigrants went to China, and returned with "paper sons" or, more rarely, "paper daughters," people who falsely claimed to be the children of U.S. citizens.

Exclusion Era: Paper Sons

Chinese Coaching Book, 1938. Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center.

The document gap allowed many Chinese immigrants to claim birthright citizenship. As U.S. citizens, they could bring their children to the U.S.

In total, about 150,000 "paper sons" successfully migrated to the U.S.

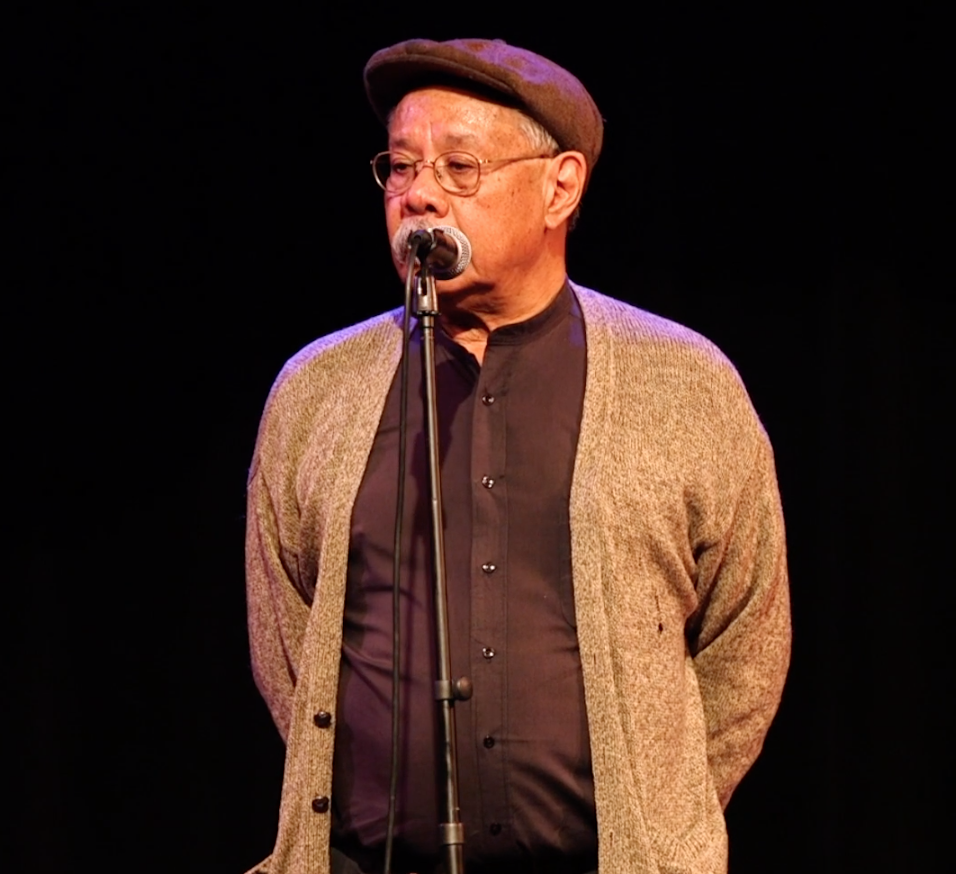

Storyteller, musician and activist Charlie Chin (b. 1944) grew up around many paper sons. This led him to create his character Uncle Toisan. "Uncle" is the term Chinese children use to address older men. Toisan (now spelled Taishan) is the county where many paper sons were from.

Click to the next slide to watch Chin performing as "Uncle Toisan".

Artistic Connection: Charlie Chin as "Uncle Toisan"

Charlie Chin performing as Uncle Toisan. Video still from a performance for East Wind Ezine.

Is this character like anyone you know?

How is this character relevant to the current immigration debate?

Watch some of this video (click on photo to access).

1943-1965: Phasing Out Exclusion

China and the U.S. were allies during World War II and the Chinese Exclusion Act was a source of tension.

Shortly after her departure, the U.S. passed the Magnuson Act, repealing the Chinese Exclusion Act.

To bolster support for China's war efforts, Soong Mei-Ling (Madame Chiang Kai-Shek), China's "First Lady," went on an eight-month speaking tour in the United States in 1943, including addresses to both houses of Congress.

Soong Mei-ling Giving a Special Radio Broadcast, unknown artist. PD, via Wikimedia Commons.

1943-1965: Phasing Out Exclusion

Watch these excerpts from the speech Soong Mei-ling (Madame Chiang Kai-Shek) gave to the U.S. Congress in 1943.

How does Soong Mei-Ling fight against prejudice? Why do you think this was an effective strategy?

The 1946 Luce-Cellar Act

The 1946 Luce-Celler Act:

- Allowed immigration from soon-to-be-independent Philippines and India

- Set a quota of 100 immigrants per year for each country

- Allowed a path towards naturalization and citizenship

President Truman Signs the Luce-Celler Act of 1946, unknown artist. PD, via Wikimedia Commons.

The Magnuson Act did not address non-Chinese Asian Exclusion. Therefore, other legislations were passed in the next decade.

The 1952 Immigration and Nationality Act:

- Repealed the Asiatic Barred Zone

- Set small quotas per year for each country (mostly 100, Japan's quota was 185), making sure that Asian immigration remained very small

- Most significantly: Allowed a path towards naturalization and citizenship for all Asians

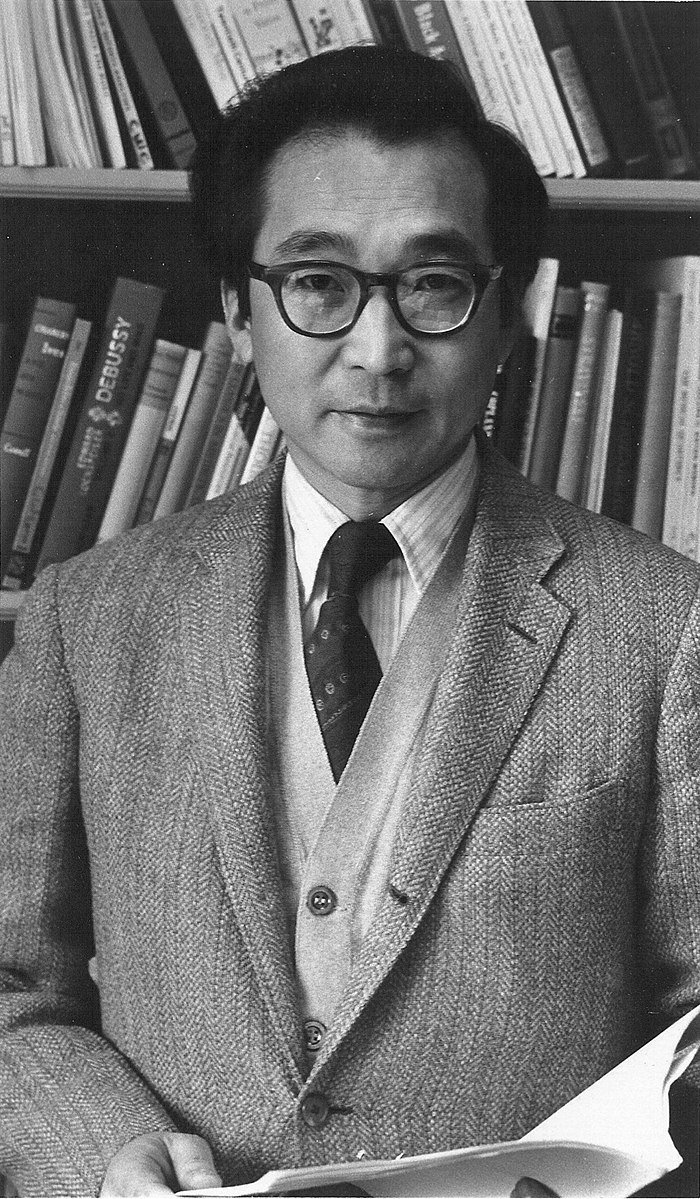

Graduation Ceremony for First-Generation Immigrants of the First Americanization Class Conducted in Japanese, San Francisco, California, by Bob Laing. CC BY-NC-SA 3.0, via Densho Encyclopedia.

Artistic Connection: Lavaan

Sharanjit Singh Dhillonn moved from India to Oklahoma in 1955, and established an interracial family a few years later.

In 2017, composer Zain Alam created a music video using Dhillonn's home videos and news footage to raise questions about how much progress the U.S. has made on racial issues since the 1950s.

Video still from Zain Alam's Music Video Lavaan. South Asian American Digital Archive.

Click to the next slide to watch the video.

Given recent events, how much do you think attitudes have changed?

The Emergence of Transnational Adoptions

- The practice of adopting infants and toddlers from other countries began after World War II.

- Between 1953 and 1962, Americans adopted 15,000 children from other countries.

- This practice increased dramatically in the 1970s (see slide 39).

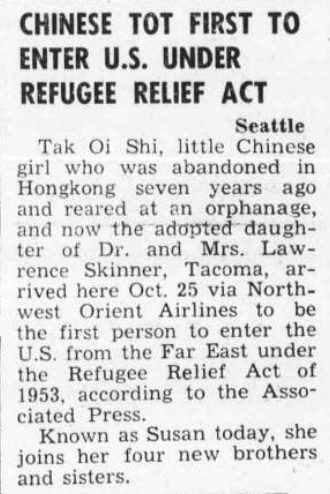

Front-Page Story about the Adoption of Tak Oi Shi from Hong Kong. November 12, 1954. Pacific Citizen Archives.

Learning Checkpoint

- What were the major turning points in the history of Asian immigration to the United States up to 1965?

- How does this history inform recent and current debates about immigration to the United States?

- What are some key factors in changing U.S. policies about immigration?

End of Component 1: Where will you go next?

Asian American Musicians and Their Immigration Stories

Component 2

20+ minutes

Immigration Narratives

Nobuko Miyamoto's grandfather came to the U.S. around 1900.

Charlie Chin's family came to the U.S. during the Exclusion Era.

Gabe Baltazar's maternal grandparents moved to Hawai‘i around 1900. His father moved there in the 1920s.

Kwan Ying Lin performed throughout the U.S. in the 1920s, and returned to the U.S. in the 1960s.

Chou Wen-Chung came to the U.S. as a student in 1946.

Susan Cheng came to New York with her family in 1956.

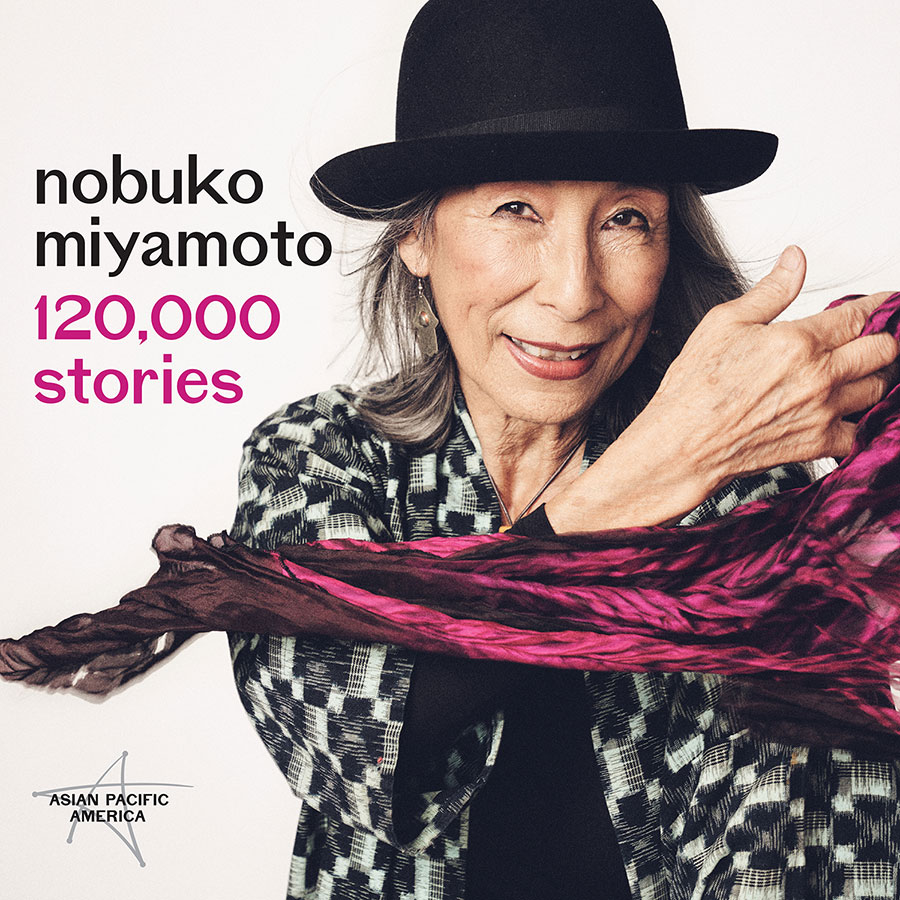

120,000 Stories, cover design by Visual Dialogue. Smithsonian Folkways Recordings.

Gabe Baltazar with Aaron Aranita, photo by Heidi Chang.

Immigration Narrative: Nobuko Miyamoto

Harry eventually settled in Parker, Idaho (40 miles NE of Idaho Falls). Nobuko spent part of World War II at his home.

Nobuko as a Child with Her Family in 1945, by Harry Hiyashida. Smithsonian Folkways Recordings.

Nobuko Miyamoto's paternal grandfather, Tokumatsu "Harry" Miyamoto, came to the United States (from Japan) to work on the railroad around 1900.

Nobuko Miyamoto: "We Are the Children" (Part II)

Since her grandfather was an immigrant and her father was born in the U.S., Nobuko is considered a third-generation Japanese American or Sansei.

In Lesson #1, we focused on the first half of the song "We Are the Children", which listed the professions of many early Asian American immigrants. In Lesson #2, we will focus on the second half (which focuses on her own generation).

How and why do you think her generation is different from earlier generations?

Nobuko Miyamoto: In Her Own Words

Watch an excerpt from this interview (17:04-21:23). Here, Nobuko Miyamoto discusses how racist legislations/regulations directly affected her parents and grandparents, and how her mother served as the family storyteller.

Is family history passed down in your family? If so, how?

Immigration Narrative: Gabe Baltazar, Jr.

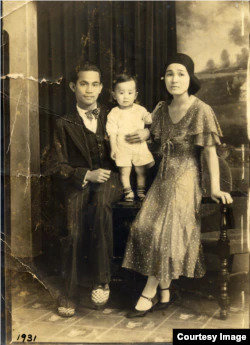

Jazz saxophonist Gabe Baltazar, Jr. (b. 1929) is the son of a second-generation Japanese American mother and a first-generation Filipino American father.

Gabe Baltazar Jr. with his parents in 1931. Courtesy of Gabe Baltazar.

His mother's parents moved to Hawai‘i to work in the plantations around 1900. His mother, Leatrice Chiyoko Haraga, was born on ‘Ōla‘a plantation, about 15 miles from Hilo, in 1907.

Gabe Baltazar Sr.'s Story

Baltazar's father, Gabe Baltazar Sr., was born in the Manila area in 1906. He went to Hawai‘i as a musician in a troupe headlined by Vicente Yerro. He was also escaping a bad family situation, so he never left.

After a stint in Los Angeles, Gabe Sr. returned to Hawai‘i to play in dance halls in Hilo and Honolulu. For many Filipino workers in the U.S., dance halls were the only outlet for entertainment. They were also the only places where they could interact with women.

Dance Hall Ticket. Thinkinglocally.org.

Gabe Baltazar Jr.'s Story

Baltazar Jr's career took off in Los Angeles in the late 1950s. He played with another Asian American jazz pioneer, Paul Togawa, and then joined the Stan Kenton Orchestra in 1960.

He returned to Hawai‘i at the height of his career in 1969, and was Assistant Director of the Royal Hawaiian Band for 16 years.

Paul Togawa Quartet at the El Sereno Club in Los Angeles in the late 1950s, with Gabe Baltazar (sax), Paul Togawa (drums), Dick Johnston (keyboard), and Buddy Woodson (bass). Courtesy of Gabe Baltazar.

Immigration Narrative: Kwan Ying Lin

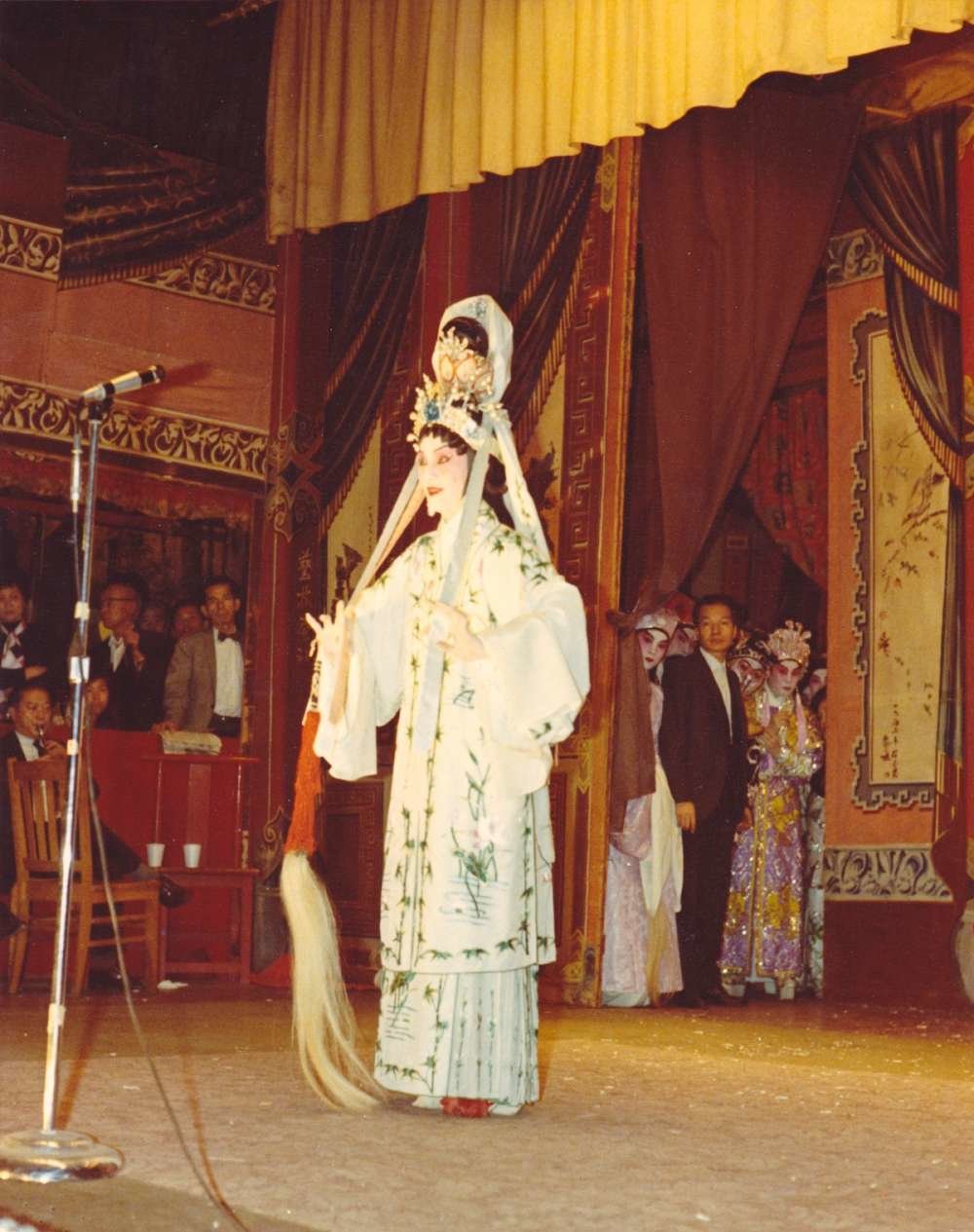

Chinese opera serves many functions: from entertainment to scaring devils, and from teaching historical or moral lessons to social commentary.

Interior of the Great China Theatre in San Francisco in the Mid-to-Late 1920s, unknown artist. Online Archive of California.

The first Chinese opera performance in the U.S. occurred in 1858.

Given its variegated functions, putting on operas was a priority for many Chinese migrants.

Kwan Ying Lin: Cantonese Opera Star

U.S. Chinese opera companies often attracted the biggest stars because they offered high salaries, great audience appreciation, and are often innovative.

Kwan Ying Lin Debuting in San Francisco in 1923, unknown artist. The OUTWARDS Archive.

Kwan Ying Lin was one of the biggest Cantonese opera stars from the 1920s to the 1950s. She made her North American debut in Vancouver in 1921.

Kwan Ying Lin: Performing in the U.S.

For much of the 1920s, Kwan performed in Seattle, San Francisco, New York, and other North American cities.

In this recording (1941), Kwan Ying Lin and Kwai Ming Yang perform an excerpt from the classic Cantonese opera Golden Leaf Chrysanthemum.

In Cantonese opera, actors are primarily trained to play one role type. Because of her versatility and star power, Kwan often played five role types in one evening during a fund-raising week.

Kwan Ying Lin: Returning to the U.S.

From the 1930s to the 1950s, she was based mostly in Asia, but Chinese Americans were able to see her in Cantonese opera films.

Eventually, she returned to the United States to be closer to family members. She gave her final performances in San Francisco in 1969, and passed away in 1979.

Kitty Tsui

Kwan's granddaughter Kitty Tsui is a poet. In her poem, "Chinatown Talk Story," she pays tribute to her grandmother's strength:

today

at the grave

of my grandmother

with fresh spring flowers,

iris, daffodil,

I felt her spirit in the wind.

i heard her voice saying:

born into the skin of yellow women

we are born

into the armor of warriors.

Kitty Tsui, unknown artist. Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center.

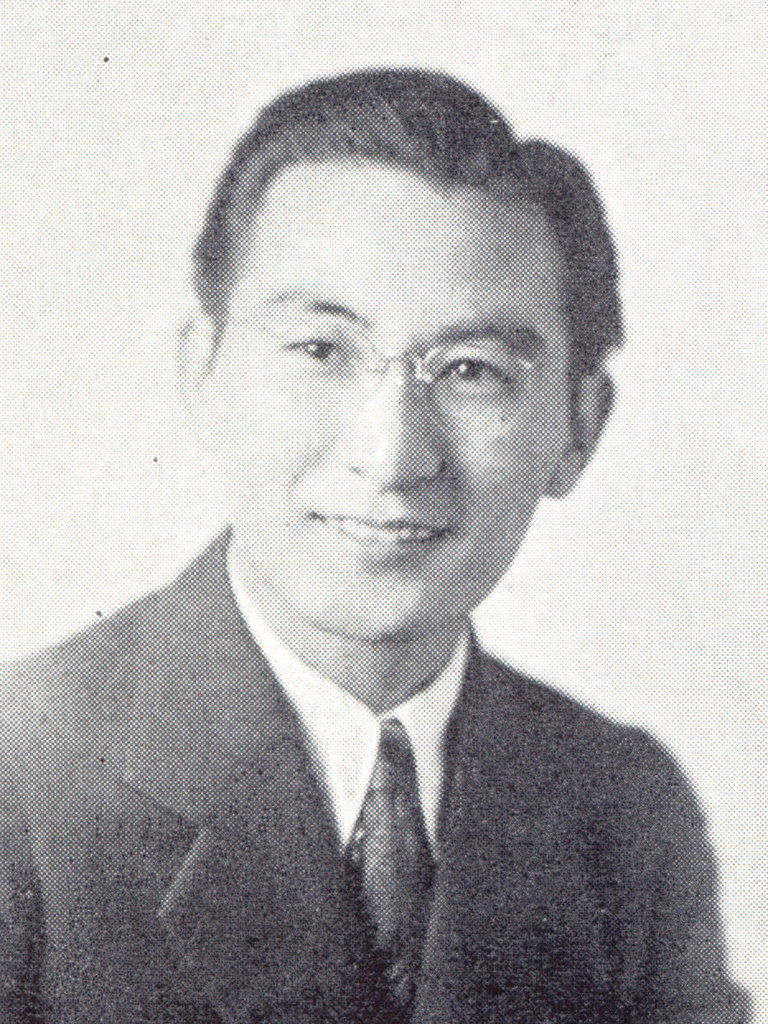

Immigration Narrative: Charlie Chin

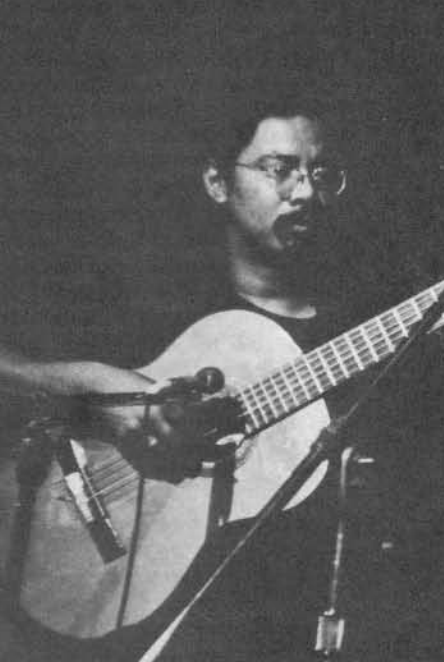

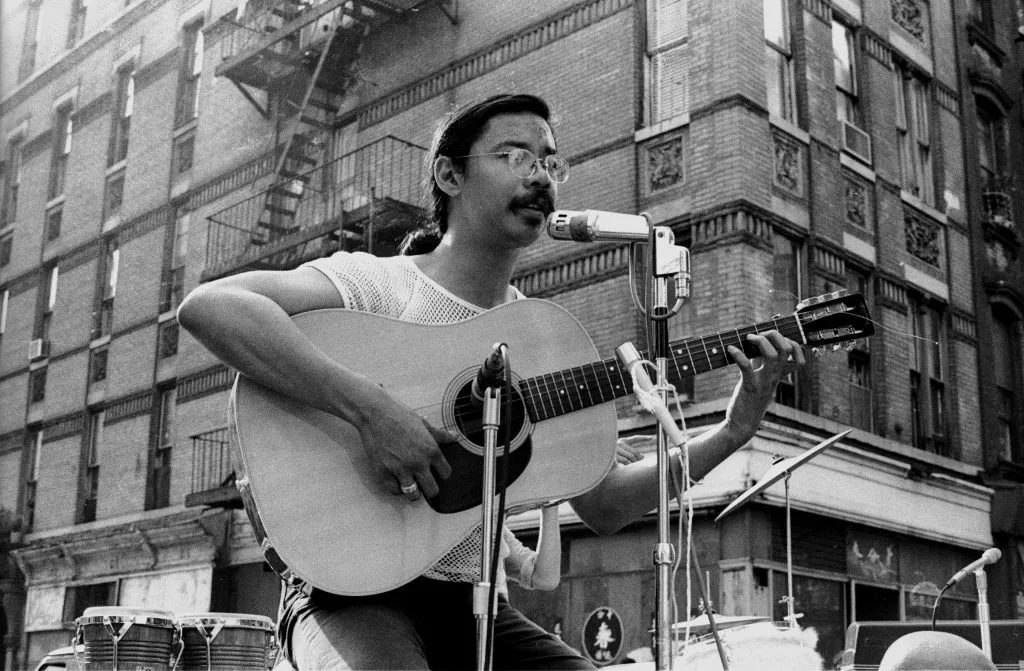

In Component #1, we saw Charlie Chin perform as his fictional "paper son" character: Uncle Toisan. We will now turn to his work as a musician.

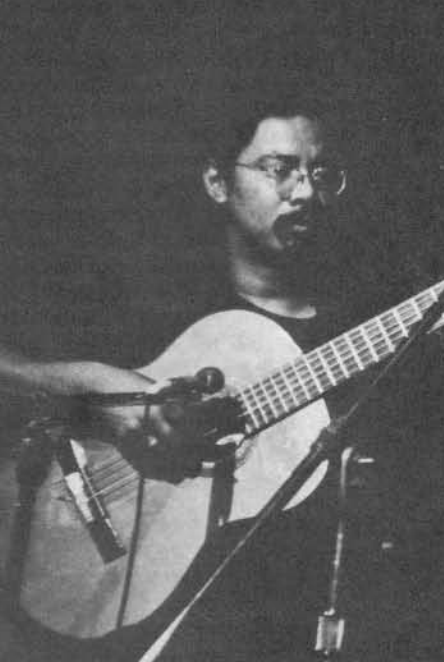

Charlie worked as a folk and rock musician in Greenwich Village in New York City in the 1960s, most prominently as guitarist and vocalist of Cat People from 1967-69 (see video on right for a sample).

Charlie Chin: In His Own Words

After teaching banjo to a White student from Kentucky, he realized, "I knew everything there was to know about them and their music, but I didn't know anything about my own" (interview with Daryl J. Maeda, 2006).

This epiphany led him to attend his first Asian American conference, to participate in Basement Workshop (NYC's first Asian American activist arts organization), and to spend six months exclusively within New York's Chinatown to "reeducate" himself and undo his "whitewashing."

Charlie Chin in the Early 1970s, unknown artist. Paredon Records.

Charlie Chin's "Story"

Charlie Chin's maternal grandparents and father all came to the US during the Exclusion Era.

- His Chinese maternal grandfather and Caribbean-Indian maternal grandmother managed to enter because they moved from Trinidad.

- His father managed to come in directly from Toisan.

Charlie Chin Performs on Henry St., New York City. Photo courtesy of Bob Hsiang. EastWindEzine.

Charlie Chin: "Wandering Chinaman"

"Wandering Chinaman" is a ballad (a story in short stanzas) about a fictional Chinese immigrant who arrived in 1925.

- What does this story reveal, if anything, about Asian American history?

- How does this narrative compare to other immigration narratives you know?

- What emotion do you think Charlie Chin is trying to elicit from listeners?

- How do you feel about the ballad's protagonist?

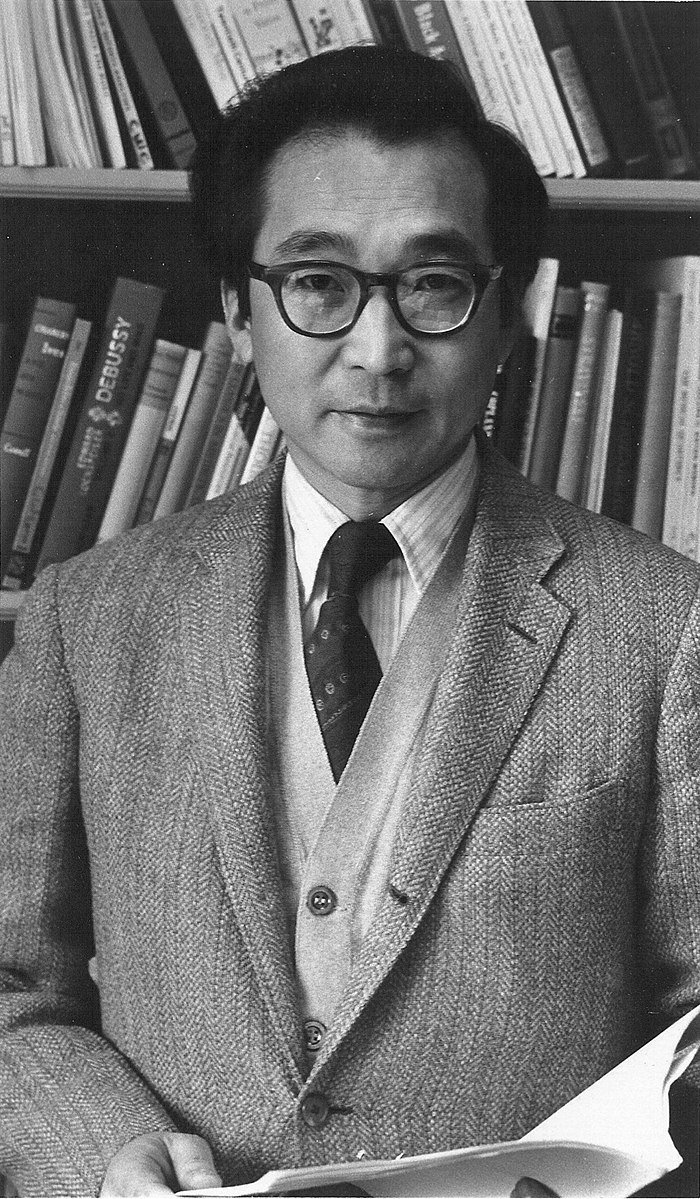

Immigration Narrative: Chou Wen-Chung

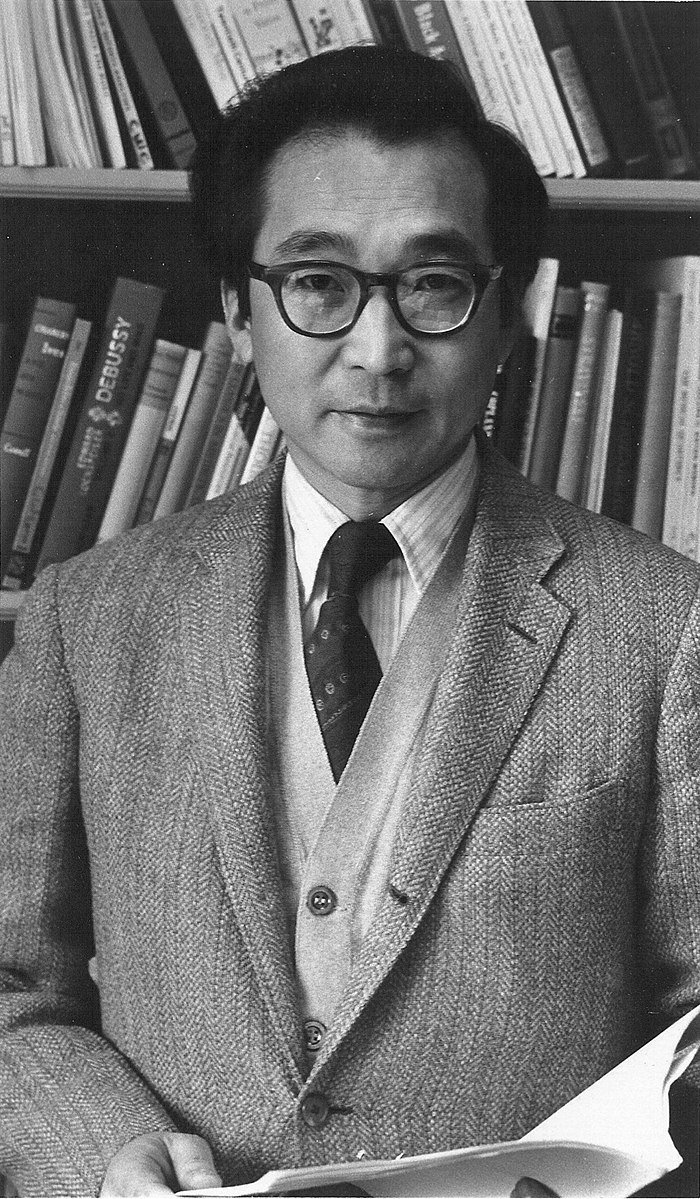

Born near Guangzhou in 1925, Chou Wen-Chung (Chou is the last name) came to the U.S. as a student in 1946. He came on a visa to study architecture at Yale University. Shortly after his arrival, he decided that he wanted to study music.

He went to Boston and requested an audition at the New England Conservatory. Even though the semester had already started, the school admitted him as a violin student, allowing him to get a new student visa.

Chou Wen-Chung in 1980, by Sumin Chou. CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Chou Wen-Chung: In His Own Words

In an interview with Frank Oteri, Chou describes his decision to change course in this way:

"For more than a week...I stayed in my room. I couldn’t make up my mind whether I really wanted to continue with this scholarship. Can you believe it? The only way I could come to this country was to get a scholarship to Yale and register as a student. So I went to see the dean, saying I had decided not to [continue]... I felt I had no choice. That shows you another important thing about being an artist. If you have conviction in your art, you have to be daring."

Chou Wen-Chung: Bridging Cultures through Music

Chou eventually became professor of music composition and a prominent administrator at Columbia University. In his compositions, he was dedicated to finding ways to combine Chinese and Western elements on an even playing field.

Through establishing the Center for US-China Arts Exchange and bringing composition students from China, he worked to promote greater understanding between the two cultures through music.

Immigration Narrative: Susan Cheng

Since 1984, Susan Cheng has been Executive Director of New York City-based Music from China, a chamber ensemble that performs both traditional and contemporary Chinese music.

At the age of 9 (in 1956), Cheng immigrated from Hong Kong to the United States. Her family settled in Manhattan's Chinatown, where she still lives. Hear about her early days in the U.S. (esp. 7:30-15:00) in the video to the right.

Susan Cheng Performs: "Birds in the Forest"

In this video, Cheng performs with Wang Guowei (Music from China Artistic Director) and Sun Li.

The piece is "Birds in the Forest" by Cantonese composer Yi Jianquan. Written in 1932, the work asks the gaohu (high fiddle) to imitate birds.

As you listen, think about: (1) What is the texture at the beginning of the piece? (2) What techniques are used to create these bird calls?

Learning Checkpoint

- How do you think the immigration history or experience of each Asian American musician highlighted in this component has affected their music making?

- Have you tried to discover or develop your personal identity? What role does music play in your identity?

- Which pieces in this component did you relate to the most or the least?

End of Component 2: Where will you go next?

Holehole Bushi / Work Songs

Component 3

15+ minutes

Plantation Workers in Hawai'i, unknown artist. PD, via USC Libraries Special Collections.

Holehole Bushi

Watch this performance of an old song–sung in a museum.

What visual and audio elements led to these ideas?

What do you think the original context and function of this song were?

About Holehole Bushi

Holehole bushis were songs sung by Japanese plantation workers in Hawai'i in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Holehole = Hawai'ian word for the dead or dying leaves of sugar cane

Bushi = Japanese word for song

About Holehole Bushi

These songs were based on melodies from the workers' homeland. Most Japanese plantation workers came from southern Japan (e.g., Hiroshima, Okinawa, Yamaguchi, Kumamoto).

The topics discussed in the lyrics are wide-ranging. They can be about the difficulties of plantation life and work, nostalgia, homesickness, love, and so on. Sometimes, the lyrics were spontaneously composed.

Harry Urata (1917-2009) was a key figure in the preservation of hole hole bushi. From the 1960s to the 1980s, he travelled throughout Hawaii to record these songs and interview the singers (pictured right).

Work Songs

Holehole bushis are a type of work song. Work songs fulfill different functions. They:

- Are sung while completing a task (often to help coordinate movement);

- Tell stories about or describe work; and/or

- Protest work.

Japanese American Agricultural Workers Packing Broccoli near Guadalupe, California, 1937, by Dorothea Lange. Library of Congress.

Holehole Bushi: Attentive and Engaged Listening

- Listen to this holehole bushi again, while following along with the English translation of the lyrics. How does the performer (Allison Arakawa) use expressive qualities to tell the story? What do you notice about the structure of the song?

- Can you hum along with the tune as you listen to the recording?

- Extension Activity: Can you hum the tune without the recording? You could also sing it on a neutral syllable (like "loo") or play it on an instrument.

Making Connections: Research a Type of Work Song

In small groups, research another type of work song, and make a brief presentation. Some possibilities are:

- Sea shanties

- Songs of enslaved African Americans

- Weaving songs

- Lumberjack songs

- Lullabies

- Unionization songs

- Cowboy songs

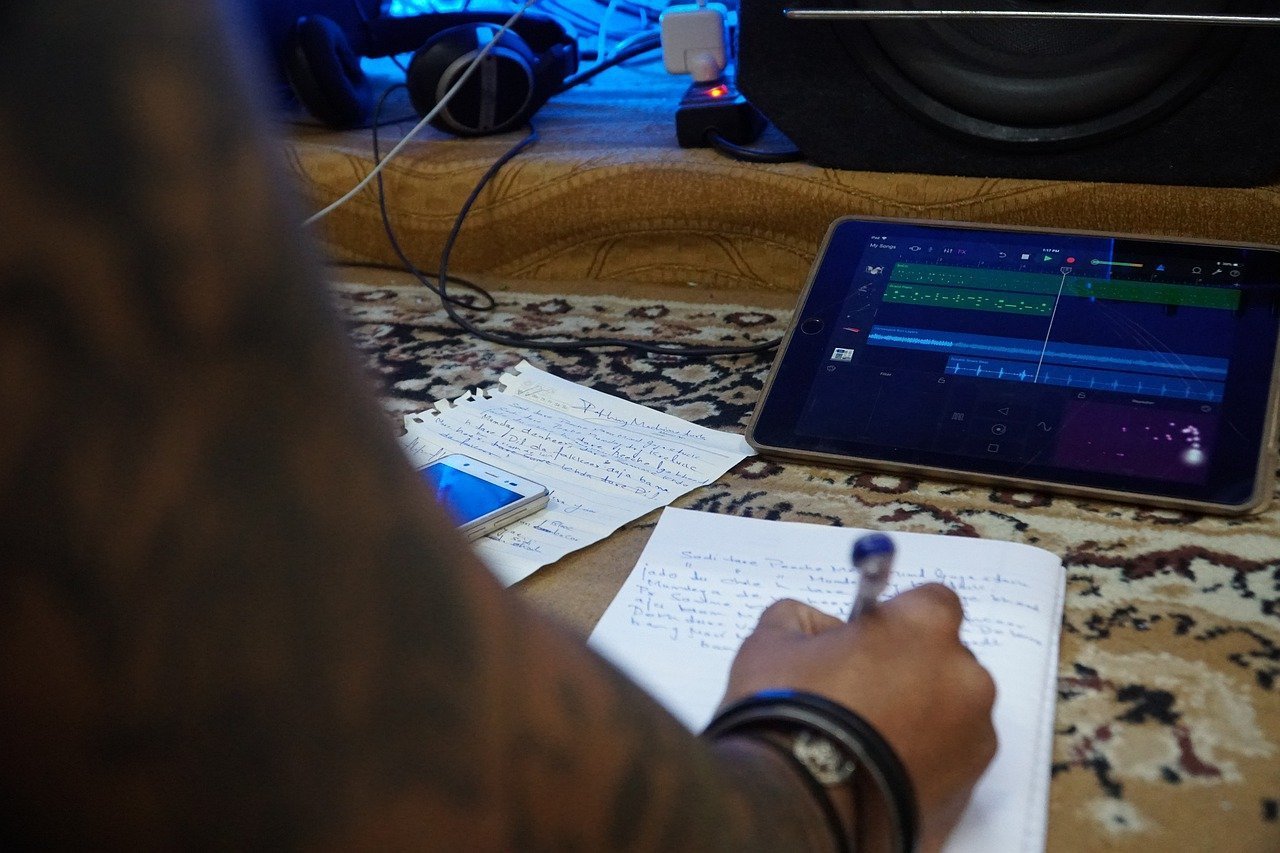

Write/Arrange Your Own Work Song

Write a work song. It can be about anything . . . school, a job you have had, chores, or a job you understand well.

If you are new to this, start by writing four lines of lyrics. Each line should have stressed syllables at similar places.

Use an existing melody that fits the prosody and mood of your lyrics (perhaps even the holehole bushi melody you just learned), or write a new melody.

Songwriting, by Arijit Saha. Pixabay.com.

Learning Checkpoint

- What is a work song? What are some types of work songs? How are different work song traditions similar and different?

- What did you learn through the process of writing/arranging your own work song?

- What is holehole bushi? What were these songs originally used for? Is preserving these songs important? Why or why not?

- What immigration period is holehole bushi associated with?

End of Component 3 and Lesson 2: Where will you go next?

Lesson 2 Media Credits

Audio courtesy of

Smithsonian Folkways Recordings

Video courtesy of

Music of Asia America Research Center

Japanese American National Museum

Images courtesy of

Smithsonian Folkways Recordings

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center

Library of Congress

Australian National University College of Asia and the Pacific

Online Archive of California

The Library Company of Philadelphia

UC Davis Library Digital Collections

National Archives, San Bruno

United States Geographical Survey

East Wind: Politics and Cultural of Asian America

South Asian American Digital Archive

Pacific Citizen Archives

The OUTWARDS Archive

USC Libraries Special Collections

Mid-Pacific Institute

© 2022 Smithsonian Institution. Personal, educational, and non-commercial uses allowed; commercial rights reserved. See Smithsonian terms of use for more information.

This project received Federal support from the Asian Pacific American Initiatives Pool, administered by the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center.

For full bibliography and media credits, see Lesson 2 landing page.