Cajun and Zydeco Music: Flavors of Southwest Louisiana

Lesson Hub 8

Stylistic Developments in Zydeco Music

How did French Creole music in Southwest Louisiana lead to what we know today as “zydeco”?

Lester Herbert – Rubboard, Peter King – Accordion, photo by Chris Strachwitz. Arhoolie Records.

Stylistic Developments in Zydeco Music

MUSIC MAKING

HISTORY & CULTURE

MUSIC LISTENING

20+ MIN

30+ MIN

45+ MIN

Zydeco: Volume One The Early Years 1949-62, cover art by Elizabeth Weil. Arhoolie Records.

The Origins of Zydeco

Path 1

20+ minutes

Zydeco Champs, cover art by Kathleen Joffrion. Arhoolie Records.

The Origins of Zydeco

Its roots lie in music that was made by French-speaking African American Louisiana Creoles as far back as the 1700s.

Wallace Gernger – Rubboard, Paul Me Zei – Accordion, photo by Chris Strachwitz. Arhoolie Records.

Zydeco music as we know it today didn't become a fully formed genre until the 1950s

Creoles in Louisiana

Creoles quickly added the unique flavor of traditional African chants, religious “juré” singers, and Caribbean rhythms to the music of the region.

Louisiana Creole Music, cover art by Ronald Clyne. Folkways Records.

Throughout the 19th century, African American Creoles settled in Southwest Louisiana (present day Acadiana), where they sharecropped the same fields as the Cajuns and entered a long period of cultural exchange.

Cultural Exchange in Southwest Louisiana

Early Creole house parties usually had bands made up of accordion and fiddle, and sometimes a rhythmic element like triangle or scrubboard.

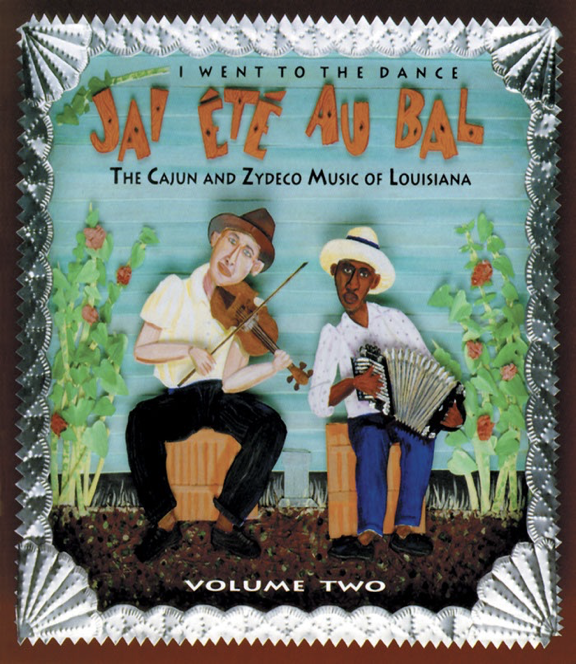

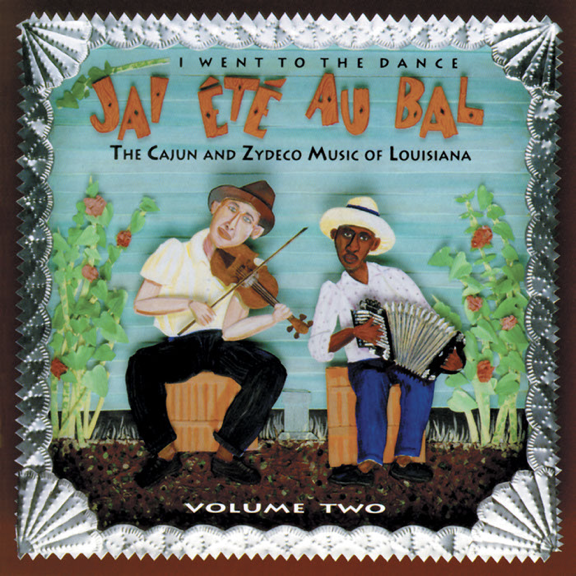

J'ai été au bal, cover art by Lynda Barry. Arhoolie Records.

Listen to an example of early Creole music

The Cajun and Creole musical styles of Southwest Louisiana developed in a parallel fashion.

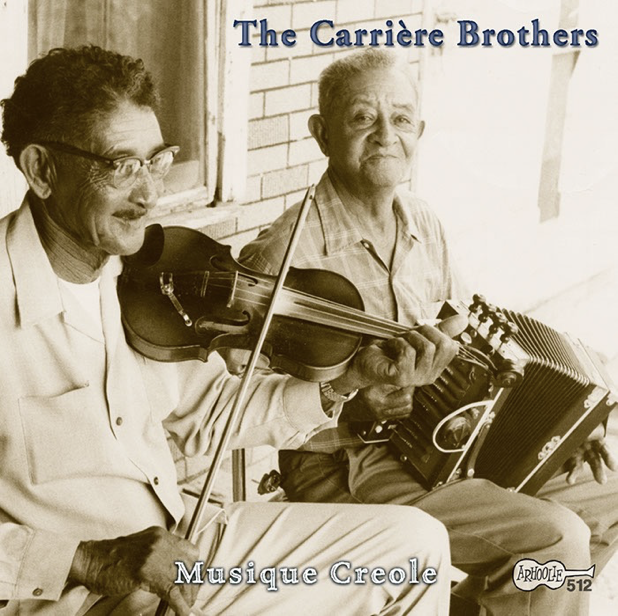

"Bébé's Stomp," by the Carriere Brothers.

Zydeco Begins to Emerge

The recordings of Amédé Ardoin from 1929, are among the first recorded examples of this new kind of playing.

Amédé Ardoin, photograph courtesy of Christopher King.

By the 1920s, at the height of the accordion's popularity, the influence of the radio (primarily blues and jazz music from New Orleans) began to find its way more prominently into Creole music style.

Text

Listen to a short excerpt from one of The Carrière Brothers’ recordings:

Zydeco Begins to Emerge

The Carrière Brothers, photograph and cover art by Chris Strachwitz. Arhoolie Records.

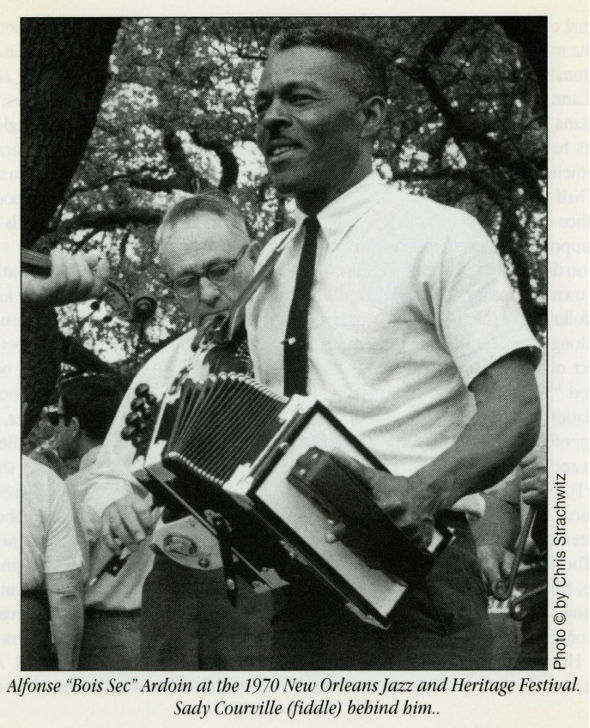

Creole musicians like Bois-Sec Ardoin (a first cousin of Amédé), The Carrière Brothers, and Canray Fontenot began to follow in Amédé's footsteps as this new sound began to emerge.

What musical sounds do you notice?

"Colinda," By The Carrière Brothers

Compare and Contrast

Watch this video clip.

How does this “style” compare to The Carrière Brothers’ recording on the previous slide?

How does this style of playing differ from traditional Cajun music? How is it similar?

Canray Fontenot: Barres de la Prison, video by Alan Lomax. Alan Lomax Archive.

Both of these recordings exemplify a style of playing called "La-La" or “Old-Time” by those who played it.

The term “La-La” now primarily refers to Creole music during and right after WWII.

Generally Speaking .....

"La-La"

Yet, this style retained the French language, had similar instrumentation to Cajun music, and was intended for dance.

Generally Speaking .....

More About "La-La"

Alfonse "Bois Sec" Ardoin at the 1970 New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival, by Chris Strachwitz. Arhoolie Records.

“La-La” tunes incorporated some stylistic characteristics that were not present in traditional Cajun music (such as syncopation and the use of blue notes).

“La-La” was the stylistic foundation from which zydeco music eventually emerged.

Learning Checkpoint

- What were some of the musical influences that ultimately led to the creation of a new musical genre called “zydeco”?

End of Path 1: Where will you go next?

Zydeco: The 1950s and Beyond

Generally Speaking .....

Path 2

30+ minutes

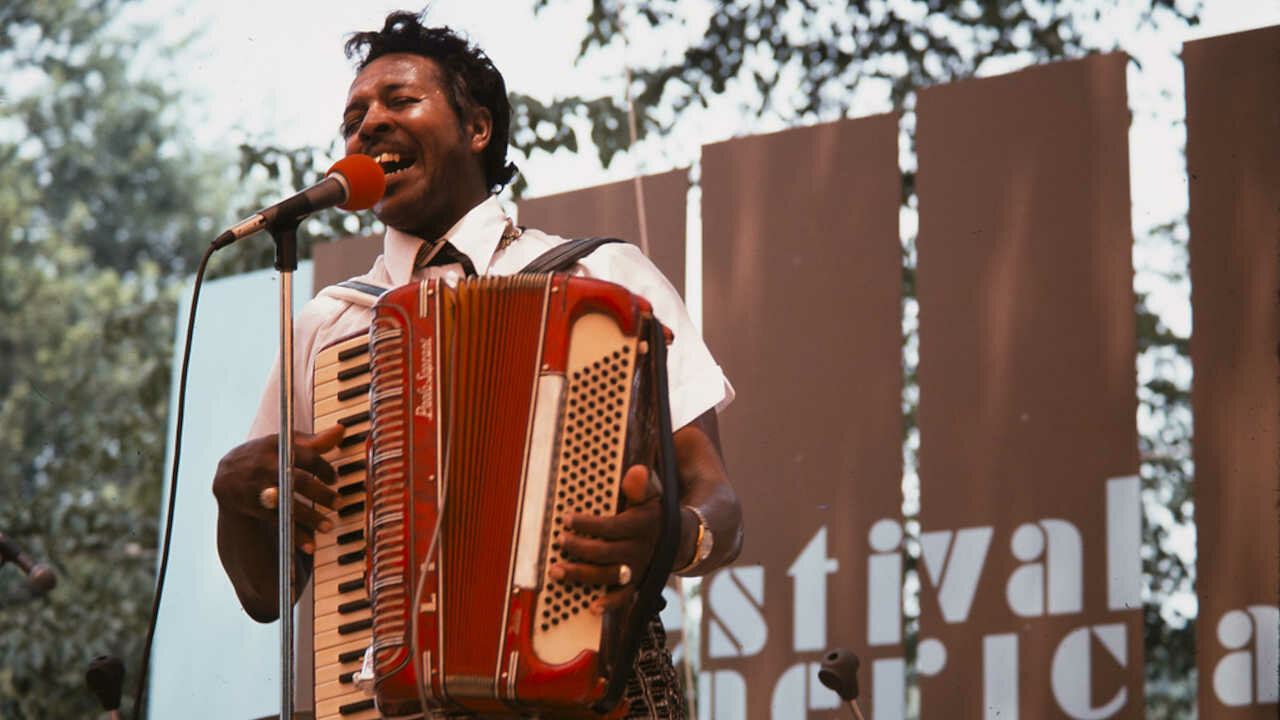

Clifton Chenier, by Reed and Susan Erskine. Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives and Collections, Smithsonian Institution.

Amplification became common practice, and amplified instruments became more easily accessible.

Generally Speaking .....

Radio and Amplification

Record Bandstand Mixer/Amplifier, Masco PA25N. by Masco. National Museum of American History.

By the 1950s, as the radio and popular culture further infiltrated rural Louisiana, the sound of Creole music began to make a permanent shift.

New Types of Accordions

Creole musicians shifted toward the triple-row diatonic and piano-key accordions, which could play in multiple keys and more easily utilize the "blue" notes characteristic of blues and Creole music.

Accordion signed by Flaco Jimenez, by Hohner. National Museum of American History.

Different types of accordions also became more accessible during this time.

Songs were played faster, and the words were simplified.

Generally Speaking .....

Prominent Percussion

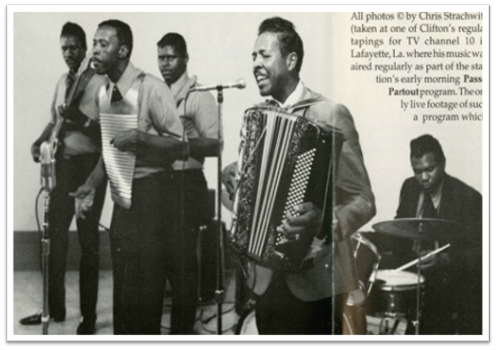

Clifton Chenier with His Band, photo by Chris Strachwitz. Arhoolie Records.

The washboard was replaced by a corrugated steel vest whose raspy sounds gave a different tone to the background percussion and could be more easily heard against the sonic palate of accordion, drums, electric guitar and bass, and other instruments.

Aiming to make music with more popular appeal, some artists from Southwest Louisiana started to write songs in English, and did not always incorporate the traditional instrumentation of Creole music.

Generally Speaking .....

Pop Culture and Language

During the 1950s, artists like Elvis Presley, Ray Charles, and Little Richard were popular on the radio.

Chenier fully blended the flavor of his native Southwest Louisiana French Creole music (La-La/Old-Time), with the popular sounds of blues, R&B, and rock and roll in order to create an entirely new genre.

Generally Speaking .....

"Zydeco" is Born

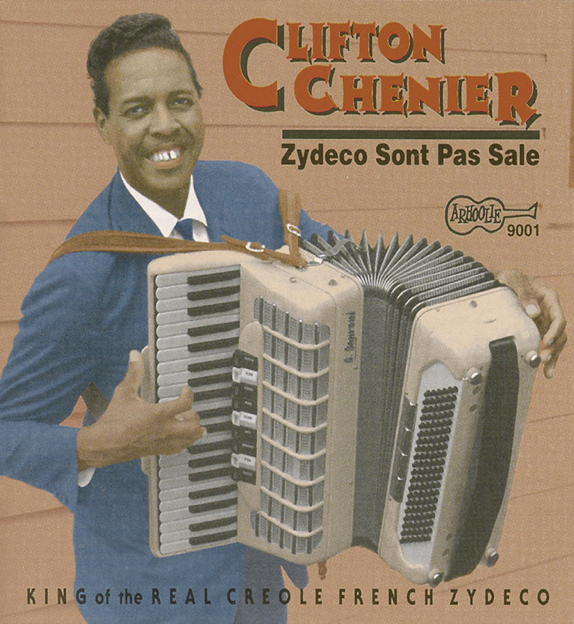

Clifton Chenier, who began making records in the 1950s, is credited as the "inventor" of Zydeco music.

Zydeco Sont Pas Sale, cover art by Elizabeth Weil. Arhoolie Records.

Listening Activity: Compare and Contrast

What similarities do you notice? How about differences?

How would you classify the genre of each example?

In this activity, you will explore the evolution of zydeco music by listening to two recordings.

- As you listen, write down anything you notice about musical elements (instrumentation, form and structure, vocal style, rhythmic patterns, etc).

Attentive Listening: "Cash Box Boogie"

What do you notice about musical elements (instrumentation, form and structure, rhythmic patterns, etc)?

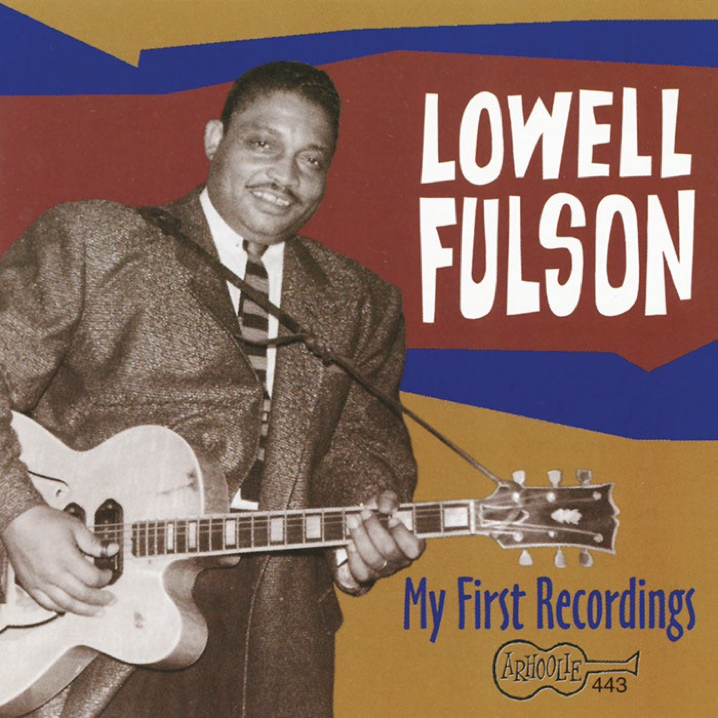

First, listen to "Cash Box Boogie" by Lowell Fulson:

Attentive Listening: "Louisiana Stomp"

What do you notice about musical elements (instrumentation, form and structure, rhythmic patterns, etc)?

- What similarities do you notice? How about differences?

- How would you classify the genre of each example?

Next, listen to "Louisiana Stomp" by Clifton Chenier:

Now, think about both songs:

About Lowell Fulson and the Blues

The first track, "Cash Box Boogie", recorded by Lowell Fulson, is an example of classic blues.

This is one type of music that was popular on the radio in the 1950s.

My First Recordings by Lowell Fulson, cover art by Wayne Pope. Arhoolie Records.

About Clifton Chenier and Zydeco

Although Chenier incorporated time structures outside the two-step and waltz, his music was still clearly intended for dancing.

The second track ("Louisiana Stomp") was an early zydeco track recorded by Clifton Chenier (the “King of zydeco").

On this track, Chenier incorporated the "walking" note structure that was common in “blues” music.

Clifton Chenier and Beyond

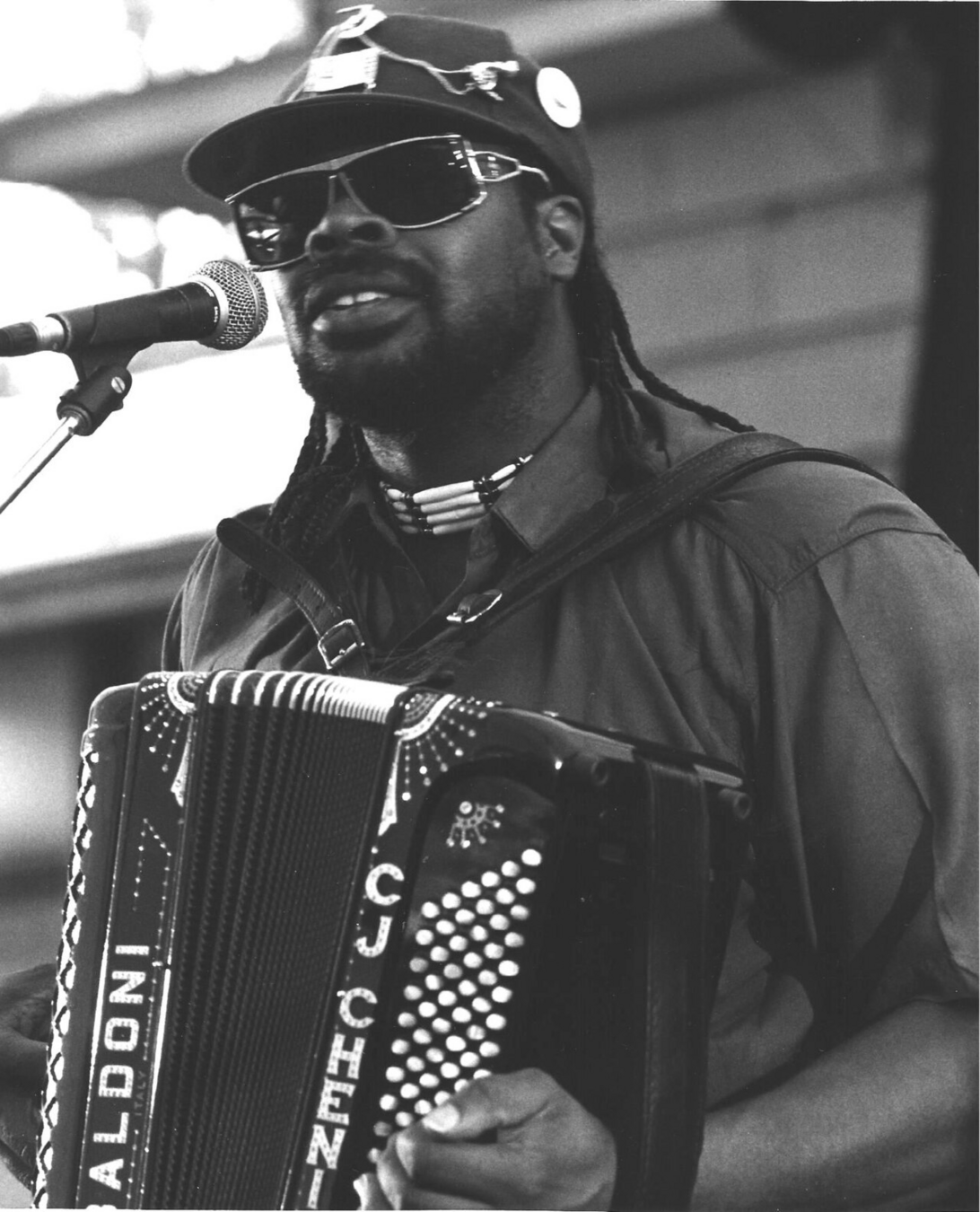

Today, traditional zydeco music is alive and well, although some young artists have continued the tradition in different ways—by adding flavors of rap and other modern music to the genre.

Clifton Chenier at the 1966 Berkeley Blues Festival, photo by Chris Strachwitz. Arhoolie Records.

With multiple radio hits, Chenier popularized zydeco music world over, and many artists today still follow in his footsteps.

Like Cajun music, zydeco music is a tradition shared with families and passed down through generations—the children of many zydeco legends are now carrying on the tradition.

Generally Speaking .....

Zydeco Today

C. J. Chenier, Son of Clifton Chenier, photograph by Phil Wight, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Flickr.

- When do you think each song was recorded?

- What type of music is this?

- What do you notice about the lyrics? What about the instrumentation?

- What do you notice about how the elements of music (rhythm, form, melody, harmony, texture) and expressive qualities (dynamics, articulation, timbre, tempo) are used?

Generally Speaking .....

Optional: Comparing La-La and Zydeco

As you listen to two new audio recordings (advance to the next slide), keep these questions in mind:

Attentive Listening: Example 1

- When do you think this was recorded?

- What type of music is this?

- What do you notice about the lyrics? What about the instrumentation?

- What do you notice about how the elements of music (rhythm, form, melody, harmony, texture) and expressive qualities are used (dynamics, articulation, timbre, tempo)?

Attentive Listening: Example 2

- When do you think this was recorded?

- What type of music is this?

- What do you notice about the lyrics? What about the instrumentation?

- What do you notice about how the elements of music (rhythm, form, melody, harmony, texture) and expressive qualities are used (dynamics, articulation, timbre, tempo)?

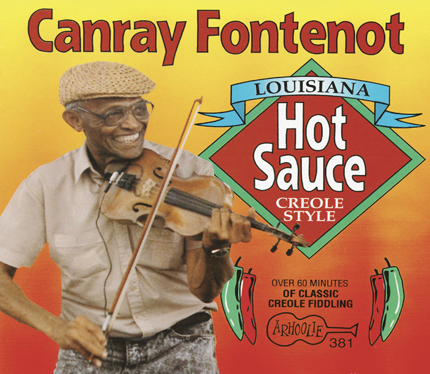

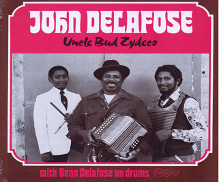

About the Recordings

Top: Creole Style, cover art by Wayne Pope. Arhoolie Records.

Bottom: Uncle Bud Zydeco, cover art by Epop Productions. Arhoolie Records.

The second track, by John Delafose, was solidly in the zydeco genre, recorded in the early 1980s.

The recordings you just heard are two versions of the same song: "Joe Pitre a deux femmes"!

The first track, by Canray Fontenot, was an example of Creole old-time (La-La) playing—something that might have been heard before 1950.

Comparing and Contrasting the Musical Sounds

After analyzing these two recordings, can you see how one grew out of the other?

- In the Creole version, the fiddle was the focal point of the music.

- In the zydeco version, the accordion was the lead instrument and there wasn’t a fiddle in the band at all.

- The zydeco version was much faster and has simplified lyrics.

The zydeco version takes elements of old-time Creole music and adds the energy, instrumentation, and attitude of rock and roll.

Learning Checkpoint

- What musical developments, beginning in the 1950s, ultimately led to the creation of zydeco – an entirely new musical genre?

End of Path 2: Where will you go next?

Arranging "The Snap Beans Aren't Salty"

Path 3

45+ minutes

Zydeco Sont Pas Sale, cover art by Beth Weil. Arhoolie Records.

“Les haricots," when spoken quickly and with a Creole accent, often came out sounding like "zydeco".

Listen to the recording:

Generally Speaking .....

“Les Haricots Sont Pas Salés”

Now you try saying “les haricots” quickly . . . Does it come out like “zydeco”?

The term "zydeco" comes from an old Creole saying: "les haricots sont pas salés."

This phrase could be thought of as the "ethos" of zydeco music —encompassing the hard times faced in southwest Louisiana and the people's dedication to "laissez les bon temps rouler" (let the good times roll).

Generally Speaking .....

"The Snap Beans Aren't Salty"

Literally translated, this phrase means “the snap beans aren't salty”—something of a colloquialism that means, “times are tough, but we're going to make the best of it” (implying there isn't any salt available to make your beans, but you're going to make them anyway).

What is your first impression?

"The Snap Beans Aren't Salty"

Arrangement: Jimmy Peters & The Ring Dance Singers

J'ai été au bal, cover art by Lynda Barry. Arhoolie Records.

Listen to a short excerpt from the first known recording of the song “Les Haricots Sont Pas Salés” (The Snap Beans Aren’t Salty).

"The Snap Beans Aren't Salty"

This recording is similar to and influenced by the early congregational shouting and clapping style of music known as juré singing.

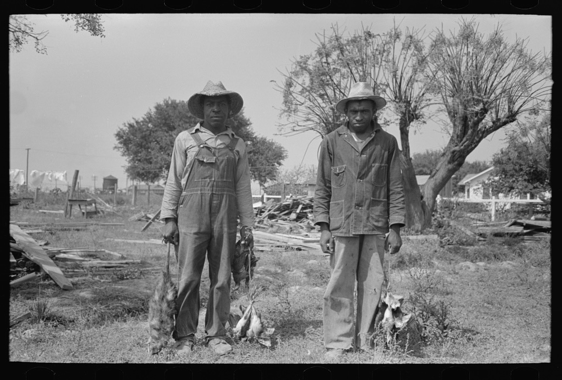

Laborers Employed by Joseph La Blanc, photo by Russell Lee. Library of Congress.

Children Fishing, photo by Marion P. Wolcott. Library of Congress.

This is an example of the Creole music one might have found on a tenant farm during the 1800s, before instruments were widely available

Arrangement: Jimmy Peters & The Ring Dance Singers

"Zydeco"

For example: "Let's go zydeco" or "Let's go to the zydeco."

Before the music of Clifton Chenier in the 1950s, the word "zydeco" was used as a kind of slang to refer to the general culture of rural Creole music, dance, and food in Southwest Louisiana.

“Zydeco Sont Pas Sales”

After Chenier's version of the classic song “Zydeco Sont Pas Salés,” became a hit, the term “zydeco” became synonymous with the entire genre . . . And zydeco music was born.

Arrangement: Clifton Chenier

So...Let's Learn It!

In this activity, we'll learn the zydeco classic "Zydeco Sont Pas Salés" (in the style of Clifton Chenier).

-

First, we’ll analyze the song.

-

Then we’ll make our own class arrangement and perform it!

Interpreting Meaning

Suggested Steps:

- Listen to the entire song while following the lyrics/translation.

- Discuss the lyrics: how does the music reflect the meaning behind the words?

- Do you feel differently about the song knowing what the words mean?

- What role do you think the lyrics played in making this song a success?

Rhythmic Practice

3. Read the lyrics aloud, line by line, incorporating the rhythm of the song into the spoken words.

- Your teacher can help you by speaking the words one line at a time, as you echo.

- The pronunciation of the lyrics is shown on the sheet music document.

Discussion Questions:

- What is the time signature and overall rhythmic feel?

- How would you describe the difference between two-step and waltz time?

Harmonic Analysis

4. Listen to the song again, this time focusing on the changing harmonies. Can you raise your hand each time the chords change?

-

This song’s harmonic structure is based on a I-V-I chord progression, which is extremely common in folk and popular music.

Reflection Question

What about this song makes it uniquely "zydeco"?

Now it’s time to make music yourselves . . . in the style of Clifton Chenier!

Arranging "Zydeco Sont Pas Salés"

Option 1: Play a percussion instrument.

- Your job is holding down the song’s duple meter feel (two-step).

Option 2: Play a chordal instrument (piano, guitar, ukulele).

- Strum the I-V-I chord progression.

Option 3: Play the melody (e.g. piano, guitar, violin, wind instrument, etc…).

Option 4: Sing!

How will you participate?

What is the feel of your class’s version of "Zydeco Sont Pas Salés"?

Did you decide to stick to a traditional "zydeco" style?

Did you add elements of older styles (like La-La/Old-Time)?

- Next time, consider trying a more “Cajun” feel, or add the influence of your favorite kind of music.

Reflecting...

Optional Connection Activity!

"Zydeco Sont Pas Salés" is said to be a reinterpretation of the Cajun tune "Hip et Taïaut."

- Although the songs have slightly different lyrics, both are somewhat nonsensical, high energy songs that have similar melodies.

- Visit Lesson 5 (Instruments of Cajun and Zydeco) to compare these songs!

"Hip et Taiaut," performed by Joe Falcon.

Learning Checkpoint

- How did your version of “Zydeco Sont Pas Salés" reflect the stylistic characteristics of zydeco music?

- Where did the term “zydeco” come from?

End of Path 3 and Lesson Hub 8: Where will you go next?

Lesson Hub 8 Media Credits

Audio courtesy of:

Smithsonian Folkways Recordings

Video courtesy of:

Alan Lomax Archive

Images courtesy of:

The Arhoolie Foundation

Smithsonian Folkways Recordings

National Museum of American History

Library of Congress

© 2022 Smithsonian Institution. Personal, educational, and non-commercial uses allowed; commercial rights reserved. See Smithsonian terms of use for more information.

This Lesson was funded in part by the Grammy Museum Grant and the Smithsonian Youth Access Grants Program, with support from the Society for Ethnomusicology and the National Association for Music Education.

For full bibliography and media credits, see Lesson 8 landing page.