Listen What I Gotta Say: Women in the Blues

Lesson Hub 6

Blues in the City

6th grade–8th grade

What happened when blues musicians migrated for better opportunities?

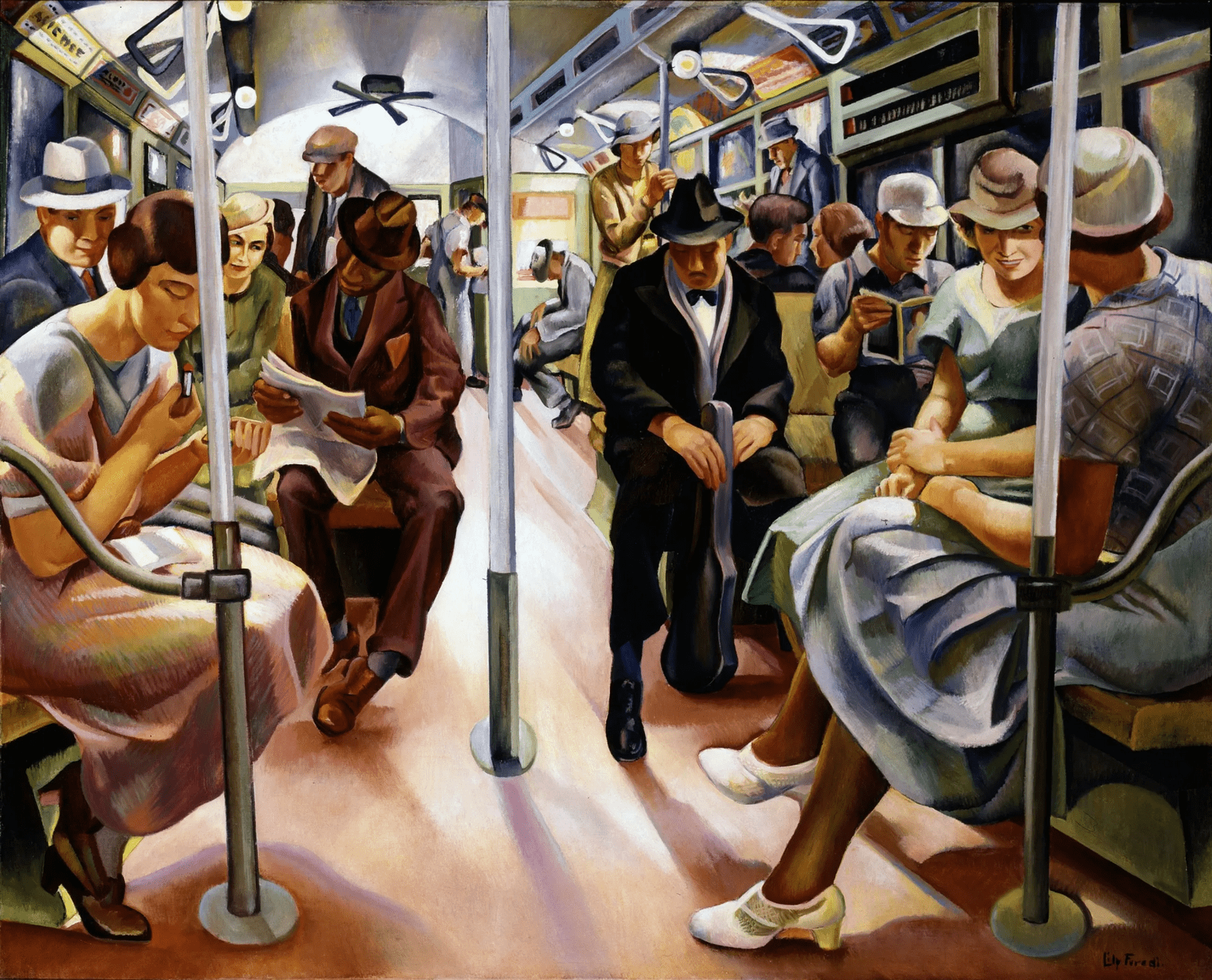

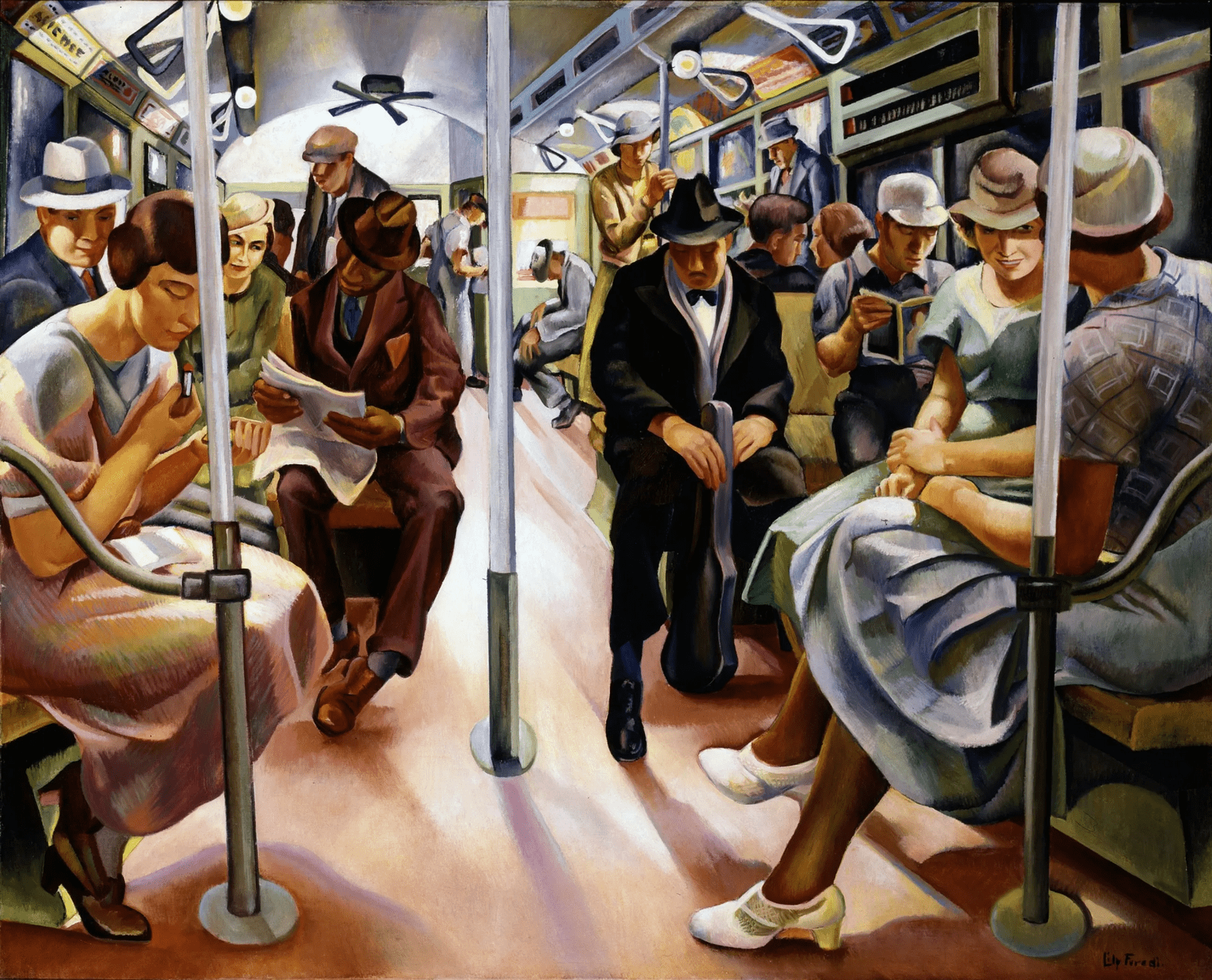

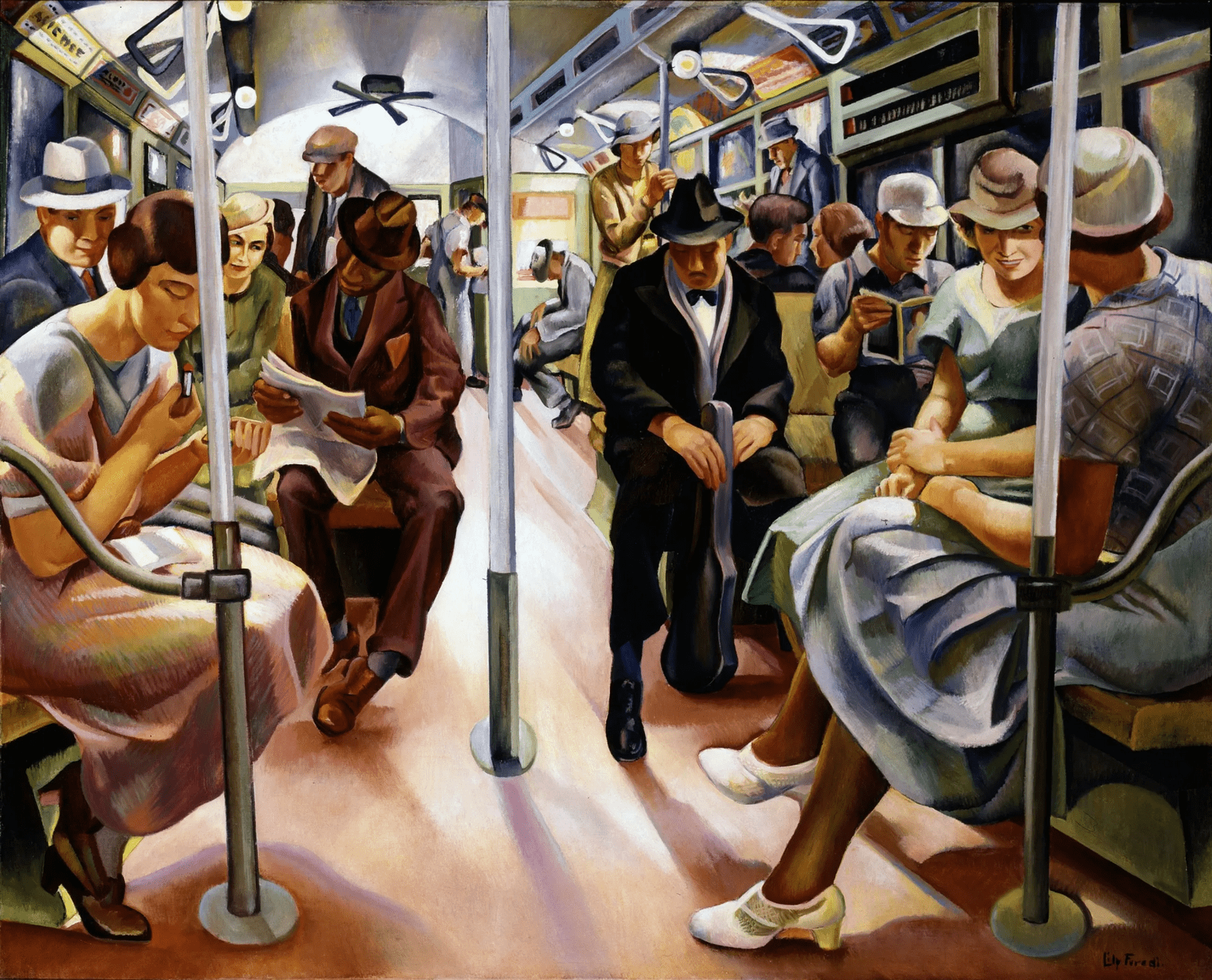

Subway, by Lily Furedi. Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Blues in the City

30+ MIN

The Great Migration and Music

Path 1

45+ minutes

Migratory Agricultural Workers on Route 27, by Jack Delano. Library of Congress.

Leaving the Deep South

This mass shift of Black people from the south to the urban north is commonly called the Great Migration.

At the turn of the 20th century, many African Americans migrated to northern urban centers (Chicago, St. Louis, DC, Harlem, Detroit, etc.).

Watch this video...

...which describes the Great Migration and explains the reasons why tens of thousands of African Americans left the south at the turn of the 20th century.

History Brief: The Great Migration, by Reading through History.

Reasons for the Great Migration

Left: Cotton Picking, Pulaski County, Arkansas, by Ben Shahn. Right: Women Welders at the Landers, Frary, and Clark Plant, by Gordon Parks. Library of Congress.

Others were trying to escape racism and violence.

Some people were trying to find better educational opportunities.

In some cases, they were looking for jobs.

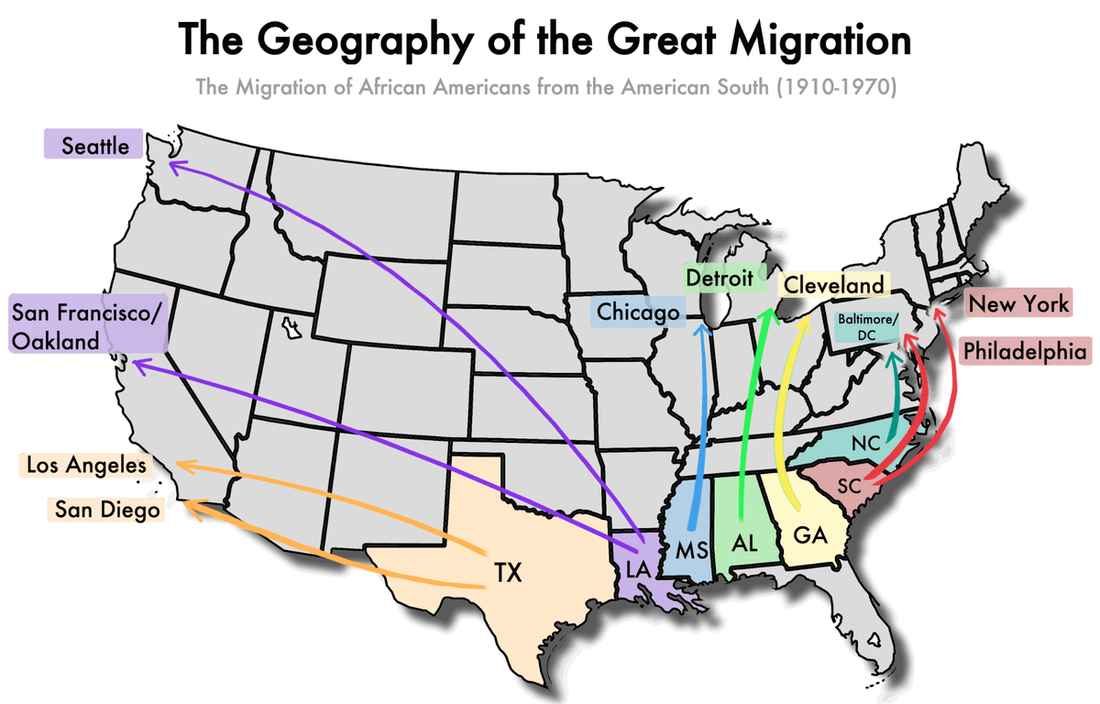

The Geography of the Great Migration, unknown maker. Priceonomics.

Activity:

Learning through Liner Notes

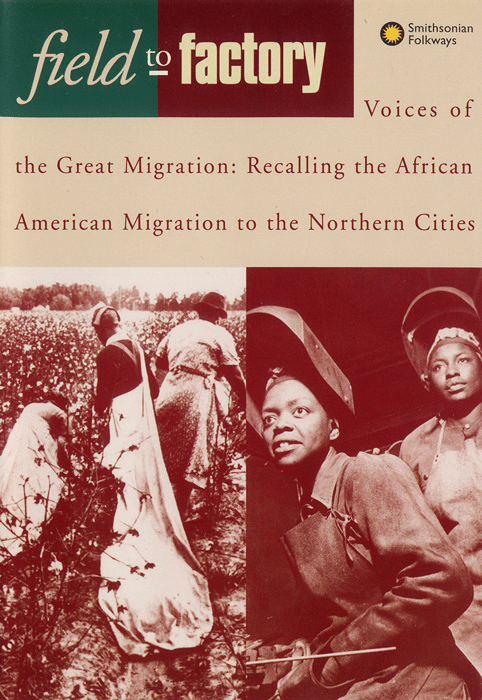

In this activity, you will learn more about the Great Migration by reading liner notes from Field to Factory - Voices of the Great Migration: Recalling the African American Migration to the Northern Cities, an album released by Smithsonian Folkways Recordings in 1994.

Field to Factory - Voices of the Great Migration: Recalling the African American Migration to the Northern Cities, cover design by Carol Hardy. Smithsonian Folkways Recordings.

Click the down arrow for more instructions.

Divide into small groups to read these sections:

-

Introduction (2-3)

-

Field to Factory: African American Migration 1915-1940 (4-5)

-

Life in the South: Why Leave? (5-7)

-

New Demands for Labor (8)

-

The Decision to Move (8-9)

-

The Trip North (9-13)

-

Was it Better or Worse? (13-14)

-

The Years that Followed (14-15)

Activity:

Learning through Liner Notes

The Stories of Migrants

Reading these primary resources and reflecting on their meaning can increase our understanding of their experiences.

Letters from migrants, collected by Emmett J. Scott, were published in The Journal of Negro History in 1919.

Reflection and Discussion

Why did African Americans feel that they had to leave the South?

Why might African Americans have felt that opportunities would not be made available for them and their families in the South?

How do you think that they felt when moving across country?

Do you think you will ever need to move to a new location to have better opportunities? Why or why not?

Generally Speaking .....

Music and Migration

What happens to music when people migrate?

Migrations: The Great Migration, by Carnegie Hall.

Watch this video to learn more:

Musical Life in the City?

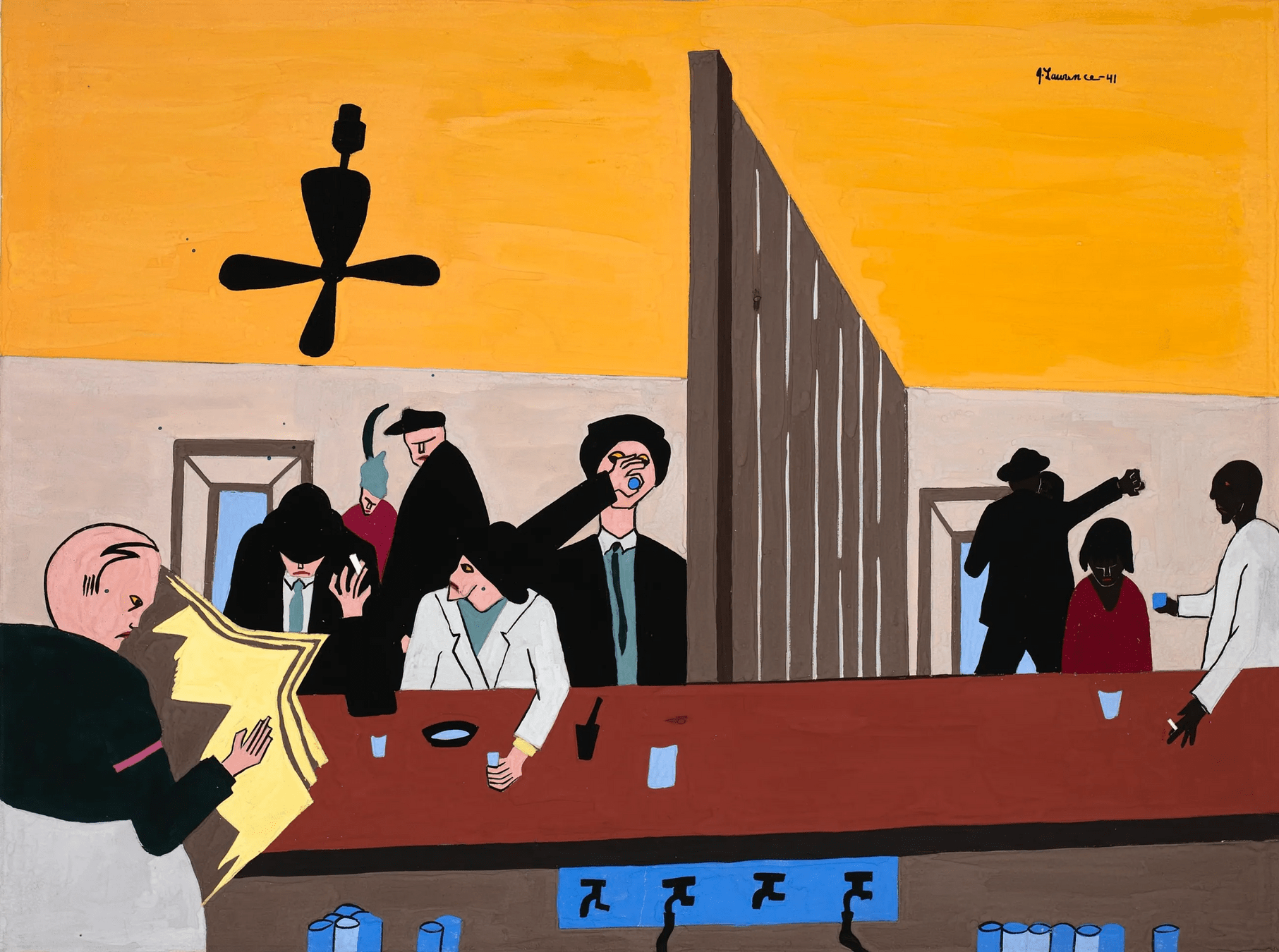

Bar and Grill, by Jacob Lawrence. Smithsonian American Art Museum.

The Great Migration brought blues musicians and their music to a wider audience. Northern and Western cities became hot spots for African American musical creativity.

Musicians began to utilize different instruments and instrumentation (electronic vs acoustic; solo performance vs ensembles), and they were able to dictate where they wanted to perform (juke joints, rent parties, venues, etc.).

Additionally, more African American audiences had the funds needed to purchase records and frequent concerts.

The Chicago Blues

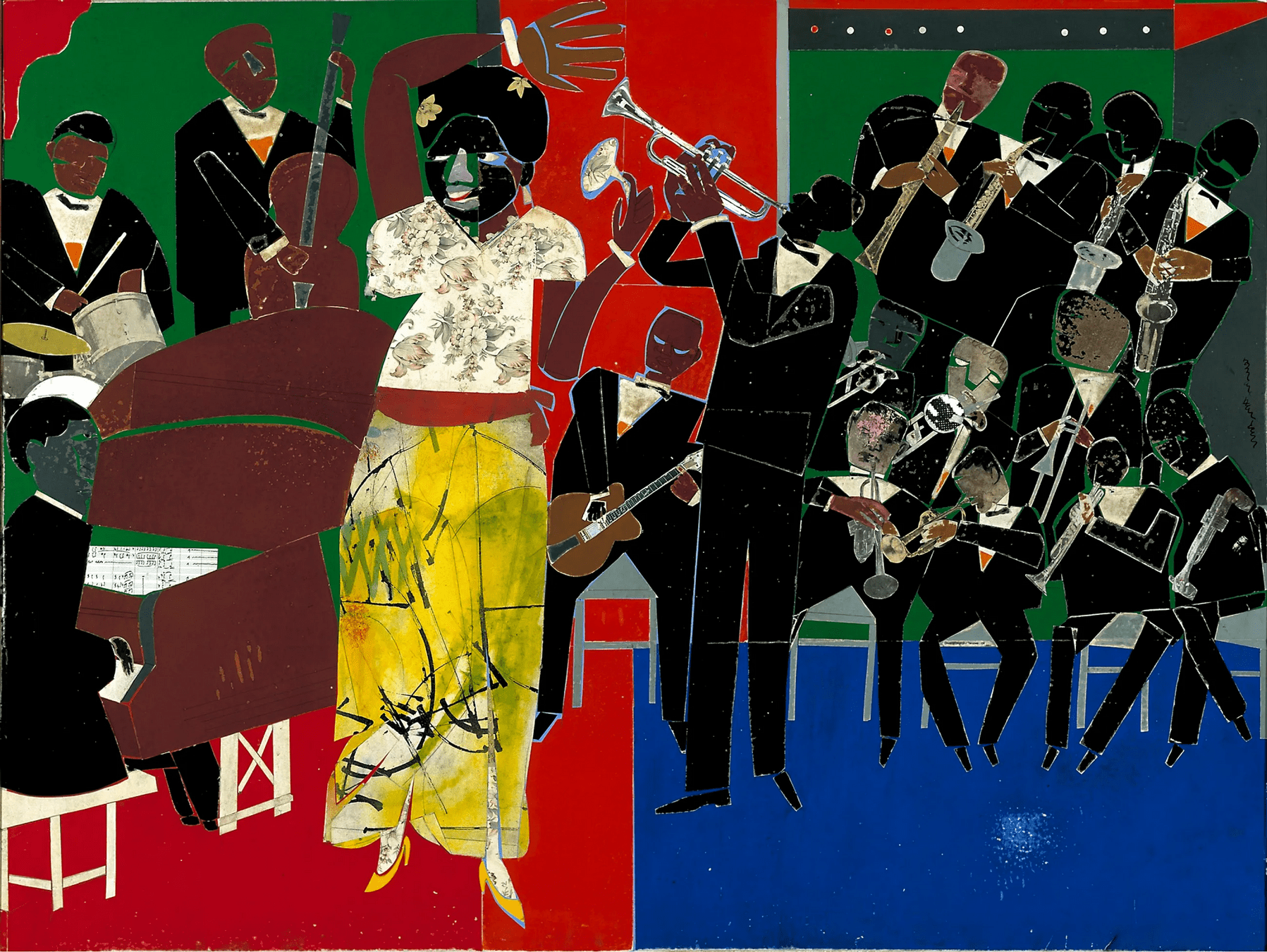

The Empress of the Blues, by Romare Bearden. Smithsonian American Art Museum.

"Wang Dang Doodle," recorded by Koko Taylor.

Chicago was one of the most easily accessible locations for blues musicians to migrate to when leaving the South, since there was a one-way train from the Mississippi Delta to Chicago.

Meet the Artist: Koko Taylor

Born on a sharecropper’s farm outside Memphis, TN, Taylor began belting the blues with her siblings on their homemade instruments.

In 1952, Taylor traveled to Chicago with nothing but, in Koko’s words, “thirty-five cents and a box of Ritz Crackers.”

Koko Taylor was one of few women who found success in the male-dominated blues world. She took her music from the tiny clubs of Chicago’s South Side to concert halls and major festivals all over the world.

Optional Activity: Compare and Contrast

The "Delta" blues is one distinct type of country blues.

"Married Woman Blues," by Big Joe Williams

"Wang Dang Doodle," by Koko Taylor

The "Chicago" blues is one distinct type of urban blues.

Relationships Between Blues Styles

1920s

1930s and Beyond

Country Blues

Urban Blues

Learning Checkpoint

- Why did many African Americans begin to migrate north to urban centers at the beginning of the 20th century?

- What happens to music when people migrate?

- How did the blues change when people migrated to more urban areas?

End of Path 1: Where will you go next?

Urbanization: Sounds of the Electric Blues

Path 2

15+ minutes

Chicago Blues, cover design by Wayne Pope. Arhoolie Records.

Attentive Listening: The Electric Blues

Listen to excerpts from these tracks.

“On The Road Again,” by Johnny Young

"Killer Diller," by Memphis Minnie

What musical/stylistic characteristics do you notice?

The Rise of Amplification

As blues musicians began to migrate to major cities across the United States, there were minor changes in instrumentation and the use of amplification became more popular.

Electric Guitar Amplifier, by Fender. National Museum of American History. Gift of Steve Cropper.

Why do you think blues musicians only began using amplification after moving to cities?

Attentive Listening: The Electric Blues

Listen again.

“On The Road Again,” by Johnny Young

"Killer Diller," by Memphis Minnie

What instruments do you hear?

What do you notice about the tempo?

Regional Styles of Urban Blues

Not all "urban" blues was the same!

Regional styles of “urban” blues developed across the United States—West Coast, New Orleans, St. Louis, Detroit, Chicago, and all major sites where Africans Americans migrated at the turn of the century or post WWI.

Left: Sister Rosetta Tharpe: America's Greatest Gospel Singing and Guitar Playing Star, by Jazzshows Limited. National Museum of African American History and Culture. Right: Bessie Smith, by Carl Van Vechten. National Portrait Gallery.

Regional Styles of Urban Blues

Gospel Blues

“Let it Shine” - Sister Rosetta Tharpe

Boogie Woogie Blues

“Wang Dang Doodle” - Koko Taylor

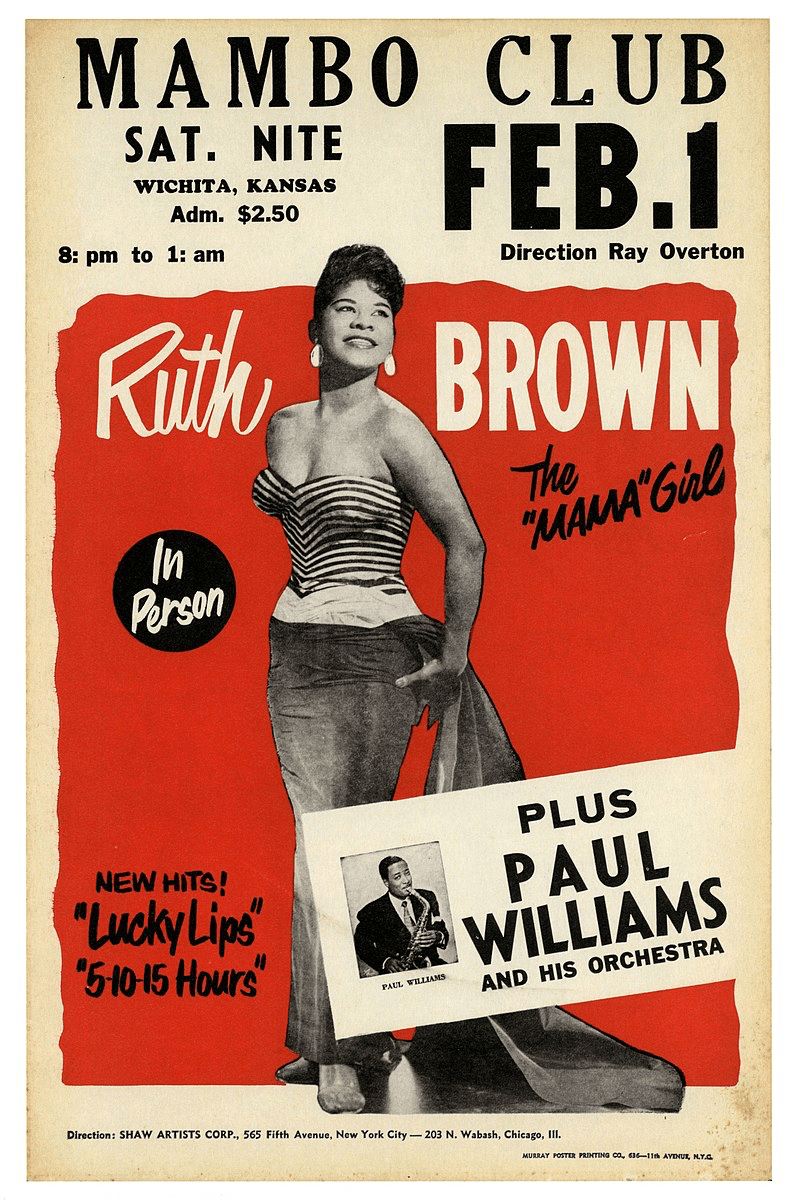

Jump Blues

“Wild Wild Young Men” - Ruth Brown

Classic Blues

“St. Louis Blues” - Bessie Smith

Rhythm and Blues

“You Better Move Out Man” - Beatrice Stewart

Ruth Brown Promotional Poster, Shaw Artist Corporation, {PD US no notice}, via Wikimedia Commons.

Learning Checkpoint

- How did migration to different urban centers influence the evolution of the blues in the United States?

-

What are some musical and stylistic characteristics of different "electric blues" sub-genres?

End of Path 2: Where will you go next?

Singing With Big Mama, Part 2

Path 3

30+ minutes

Big Mama Thornton with Band, by Chris Strachwitz. Arhoolie Records.

Who Was Big Mama Thornton?

Willie Mae "Big Mama"Thornton (1926-1984) was born and raised in rural Alabama, leaving home at age 14 to tour with a group called the Hot Harlem Review.

Big Mama Thornton, Berkeley Folk Festival, photo by Kelly Hart; © Northwestern University. Courtesy of Berkeley Folk Music Festival Archive, Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections, Northwestern University Libraries.

Around 1950, she recorded her first hit song, "Hound Dog." Suddenly, she was in high demand and performed in many cities throughout the United States and beyond.

Women in the Blues!

We often forget about the substantial role that women played in forming and popularizing the blues.

Big Mama Thornton, Arms Crossed, ©Jim Marshall Photography LLC.

Big Mama Thornton was instrumental in extending the reach of the blues to white audiences.

- Janis Joplin- “Ball and Chain”

-

Elvis Presley- "Hound Dog"

In fact, two leading rock ‘n’ roll artists were inspired by her music and performance style:

Compare and Contrast

What similarities and differences do you notice between these versions of the songs?

"Ball N' Chain," by Big Mama Thornton

"Ball and Chain," by Janis Joplin

"Hound Dog," by Big Mama Thornton

"Hound Dog," by Elvis Presley

Singing With Big Mama (Part 2)!

To better understand Big Mama Thornton's style and how her music was key in crossing race barriers, we will perform one of her songs: "I'm Feeling Alright".

Let's start by listening while tapping along on beats 2 & 4.

Attentive Listening: "I'm Feeling Alright"

Listen to short excerpts from Big Mama's "I'm Feeling Alright".

Think about a different question each time:

What do you notice about the structure?

How would you describe the tempo?

How does it make you feel?

What instruments do you hear?

Listening for the 12-Bar Blues

This song uses a standard 12-Bar Blues chord progression.

| I | IV | I | I |

|---|---|---|---|

| IV | IV | I | I |

| V | IV | I | I-V |

Standard 12-bar blues chords

"I'm Feeling Alright"

Listening for AAB Lyrical Form

This song uses a standardized lyrical form called AAB:

I'm feeling alright this morning, because my baby's coming home

A

A

I got a letter yesterday that he’ll be there this early morning

B

"I'm Feeling Alright"

The "blues stanza" generally consists of three lines, each of which is set to four measures of music.

Hey - I'm feeling alright this morning, because my baby's coming home

Engaged Listening: "I'm Feeling Alright"

Now that you're familiar with the tune, it's time to sing along with Big Mama!

A

A

B

Blues music is often learned "by ear."

I'm feeling alright this morning, because my baby's coming home

Hey - I'm feeling alright this morning, because my baby's coming home

I got a letter yesterday that he’ll be there this early morn

Generally Speaking .....

Suggestions and notes:

Perform "I'm Feeling Alright"

- Sing the whole song with and without the recording.

- If possible (when singing without the recording), sing in the key appropriate to the voices of the students (e.g. C, for young voices, with middle C being the lowest pitch, and the song having a range of an octave).

- Teachers (or students) can consider adding piano or guitar accompaniment and/or rhythm section (especially at first, keep it simple!).

- Discuss performance criteria as a class . . . Remember to sing expressively.

- Learn a blues scale and practice improvising short melodic riffs.

- Practice, refine, and perhaps even perform for an audience.

Lyrics of "I'm Feeling Alright" by Big Mama Thornton

I'm feeling alright this morning, because my baby's coming home (2x)

I got a letter yesterday that he’ll be there this early morn

I got the blues at midnight, I'll be so glad when its day (2x)

Cause I’m so in love with my baby because he’s coming home today

Instrumental Break

Instrumental Break

I love my baby child better than I do myself (2x)

I gotta let the whole world know about it cause I don’t want nobody else

I love my better baby better than I do anything in this world (2x)

Cause he’s the only boy and mama is the only girl

Attentive Listening: "I'm Feeling Alright" (different version)

Next, you will engage with a different version of this song (also recorded by Big Mama Thornton).

- Tap or pat along on beats 2 & 4.

- Sing along on the first verse.

What similarities and differences do you notice between these versions?

Lyrics of "I'm Feeling Alright" by Big Mama Thornton

I'm feeling alright this morning, because my baby's coming home (2x)

I got a letter yesterday that he’ll be there this early morn

I got the blues at midnight, I'll be so glad when its day (2x)

Cause I’m so in love with my baby because he’s coming home today

Instrumental Break

Instrumental Break

I love my baby child better than I do myself (2x)

I gotta let the whole world know about it cause I don’t want nobody else

I love my better baby better than I do anything in this world (2x)

Cause he’s the only boy and mama is the only girl

Reflection and Discussion

How did you feel as you were engaging with this version of the song?

Why do you think Big Mama Thornton changed the tempo for this version?

Which version did you like better, and why?

Generally Speaking .....

Suggestions and notes:

Optional: Create your own version of "I'm Feeling Alright"

- Sing the whole song again with each recording.

- If possible (when singing without the recording), sing in the key appropriate to the voices of the students (e.g. C, for young voices, with middle C being the lowest pitch, and the song having a range of an octave).

- Teachers (or students) can consider adding piano or guitar accompaniment and/or rhythm section (especially at first, keep it simple!).

- Each time you practice, interpret it in a new way (change something).

- Discuss how you felt about each version and make choices about how you would like to interpret the song for performance.

- Practice, refine, and perhaps even perform for an audience.

"I'm Feeling Alright"

"I'm Feeling Alright" (fast version)

Lyrics of "I'm Feeling Alright" by Big Mama Thornton

I'm feeling alright this morning, because my baby's coming home (2x)

I got a letter yesterday that he’ll be there this early morn

I got the blues at midnight, I'll be so glad when its day (2x)

Cause I’m so in love with my baby because he’s coming home today

Instrumental Break

Instrumental Break

I love my baby child better than I do myself (2x)

I gotta let the whole world know about it cause I don’t want nobody else

I love my better baby better than I do anything in this world (2x)

Cause he’s the only boy and mama is the only girl

"I'm Feeling Alright"

"I'm Feeling Alright" (fast version)

More Reflection and Discussion

Did changing the musical elements and expressive qualities change the “essence” of the song/your performance?

What are some reasons why performers might change their interpretation based on the performance context and/or audience?

Did the music become less or more personal when you performed for an audience? How did the audience respond?

Learning Checkpoint

- How can performers convey the intent of a musical composition and why do they change their interpretation from one performance to the next?

- What are some musical and stylistic characteristics of Big Mama Thornton's song, "I'm Feeling Alright"?

- Why were Big Mama's contributions so important to the evolution of blues music and other American musical styles?

End of Path 3 and Lesson Hub 6: Where will you go next?

Lesson 6 Media Credits

Audio courtesy of

Smithsonian Folkways Recordings

Columbia Records

Document Records

Atlantic Records

Images courtesy of

The Arhoolie Foundation

Jim Marshall Photography, LLC

National Museum of African American History and Culture

Northwestern University Libraries

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Smithsonian Folkways Recordings

National Portrait Gallery

National Museum of American History

Library of Congress

© 2022 Smithsonian Institution. Personal, educational, and non-commercial uses allowed; commercial rights reserved. See Smithsonian terms of use for more information.

This Lesson was funded in part by the Grammy Museum Grant and the Smithsonian Youth Access Grants Program, with support from the Society for Ethnomusicology and the National Association for Music Education.

For full bibliography and media credits, see Lesson 6 landing page.