Listen What I Gotta Say: Women in the Blues

Lesson Hub 12

The Blues Influence

6th grade–8th grade

What’s the link between blues music, gospel music, American popular music, and hip hop?

Female Rappers, Class of '88, photo © Janette Beckman. National Museum of African American History and Culture.

The question to consider in this lesson is . . .

Lesson 12: The Blues Influence

45+ MIN

Building the Foundation of Popular Music

Path 1

25+ minutes

Big Mama Thornton, Arms Crossed, ©Jim Marshall Photography LLC.

From Blues to American Pop

Did you know that American popular music has its roots in blues music?

Lyrical Form: The "Blues" Stanza

After Elvis, many other pop songs continued to adhere to the classic blues lyrical form: AAB

Consider the lyrics to one of America's favorite pop songs:

“Hound Dog,” performed by Elvis Presley

A: You ain't nothin' but a hound dog/ Cryin' all the time

A: You ain't nothin' but a hound dog/ Cryin' all the time

B: Well, you ain't never caught a rabbit and you ain't no friend of mine

Harmonic Form: The 12-Bar Blues

The 12-bar blues harmonic form form has shaped much of American popular music during the 20th century

| I | I or IV | I | I7 |

|---|---|---|---|

| IV | IV | I | I7 |

| V | V or IV | I | I or V |

Standard 12-bar blues chords

Fun with Chord Changes

| I | I or IV | I | I7 |

|---|---|---|---|

| IV | IV | I | I7 |

| V | V or IV | I | I or V |

Standard 12-bar blues chords

- Each time you hear a new chord (the chord change), clap your hands.

- Try to sing the chord changes (sing the root note at the beginning of each measure).

- Play the chord changes (root note) on an instrument.

Your teacher will play the 12-bar blues progression.

12-Bar Blues in Popular Music

One popular song that draws from the 12 Bar Blues harmonic form is U2's "I Still Haven't Found What I'm Looking For".

As you listen to the first verse, try to identify differences between the chord structure used in this song and the diagram shown below.

| I | I or IV | I | I7 |

|---|---|---|---|

| IV | IV | I | I7 |

| V | V or IV | I | I or V |

"I Still Haven't Found What I'm Looking For"

"I Still Haven't Found What I'm Looking For":

| I | I | I | I7 |

|---|---|---|---|

| IV | IV | I | I7 |

| V | IV | I | I |

12-Bar Blues:

| I | I | I | I |

|---|---|---|---|

| IV | IV | I | I |

| V | IV | I | I |

| V | IV | I | I |

Generally Speaking .....

Remaking the "Blues"

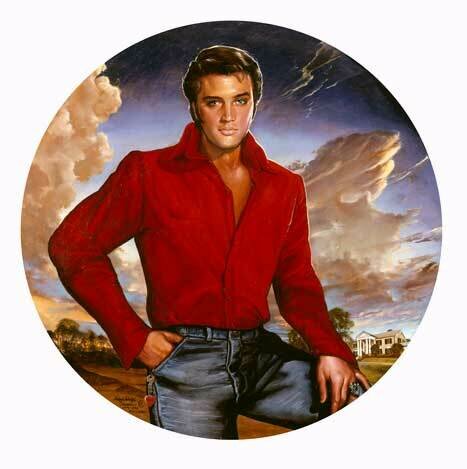

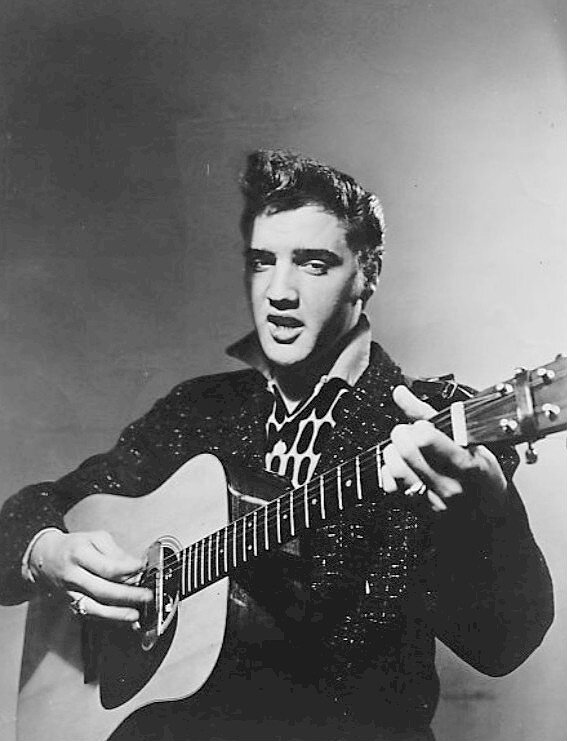

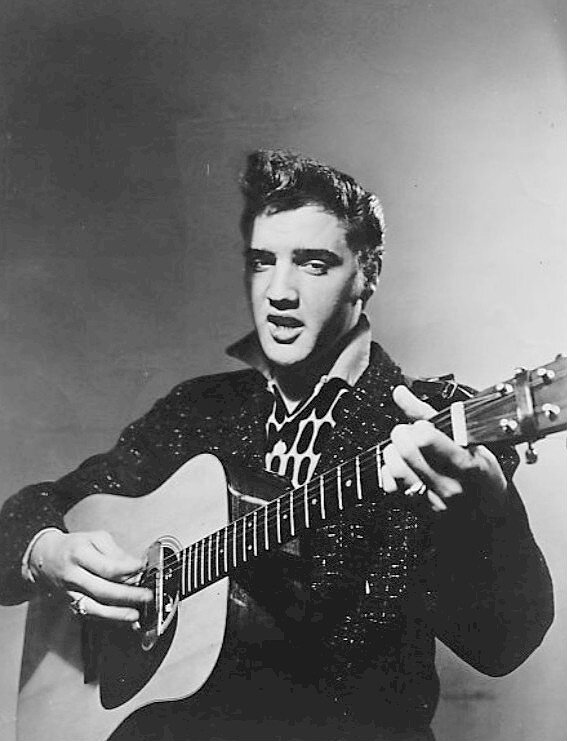

Left: Big Mama Thornton, Arms Crossed, ©Jim Marshall Photography LLC. Above: Elvis Presley, First National Television Appearance, by CBS Television, PD US no notice, via Wikimedia Commons.

Through the years, many American popular musicians have been inspired to remake blues hits.

For example, did you know that Elvis Presley's popular version of "Hound Dog" was actually a remake of Big Mama Thornton's song?

Generally Speaking .....

"Hound Dog": Compare and Contrast (Optional)

What similarities and differences do you notice between these versions of the famous song, "Hound Dog"?

Big Mama Thornton

Elvis Presley

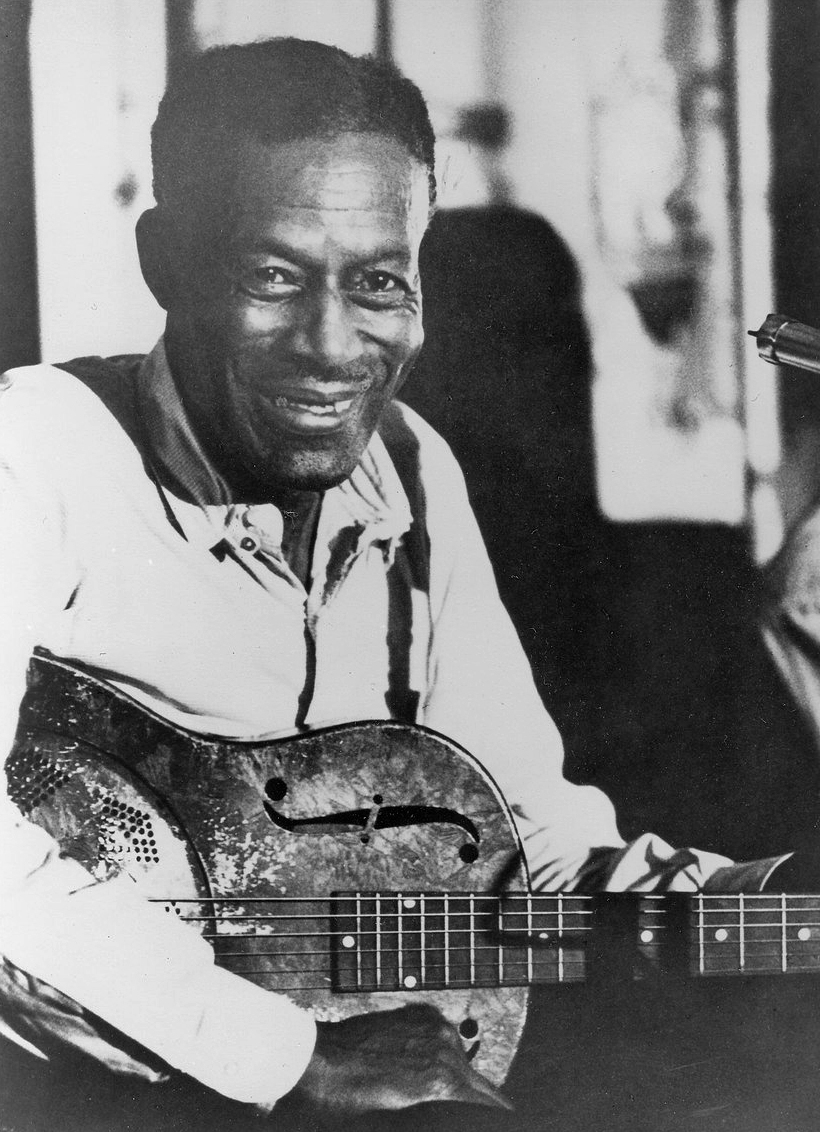

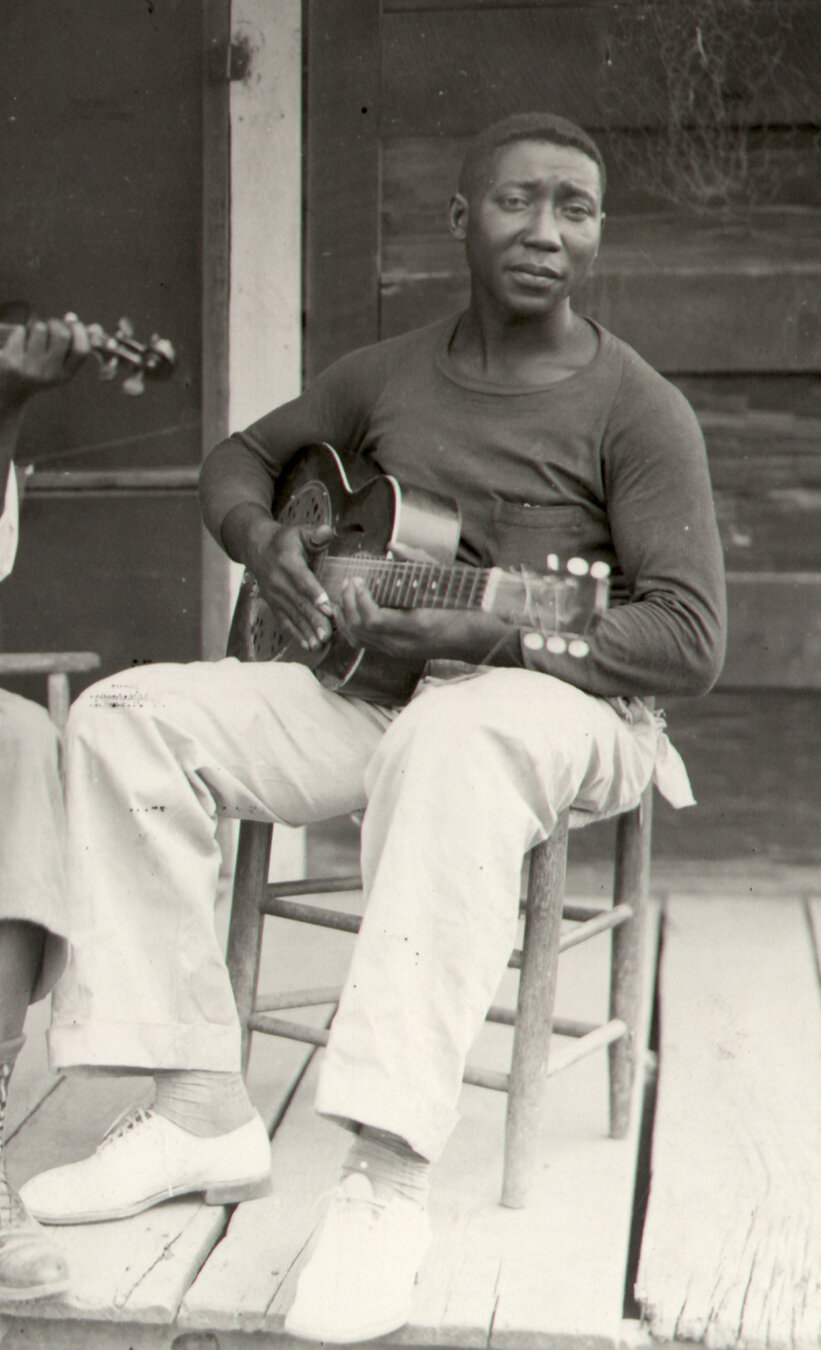

Remaking the Blues: Son House's "Death Letter"

Another example of a blues song that has been remade is Son House’s “Death Letter Blues":

-

What instruments do you hear?

-

How would you describe the tempo?

-

Can you count the measures of the 12 Bar Blues form?

-

Can you clap along on beats 2 & 4?

-

How would you describe Son House’s vocal quality?

-

What is the song about (can you understand the lyrics)?

Attentive and Engaged Listening:

Son House, unknown photographer, {{PD-US-expired}}, via Wikimedia Commons.

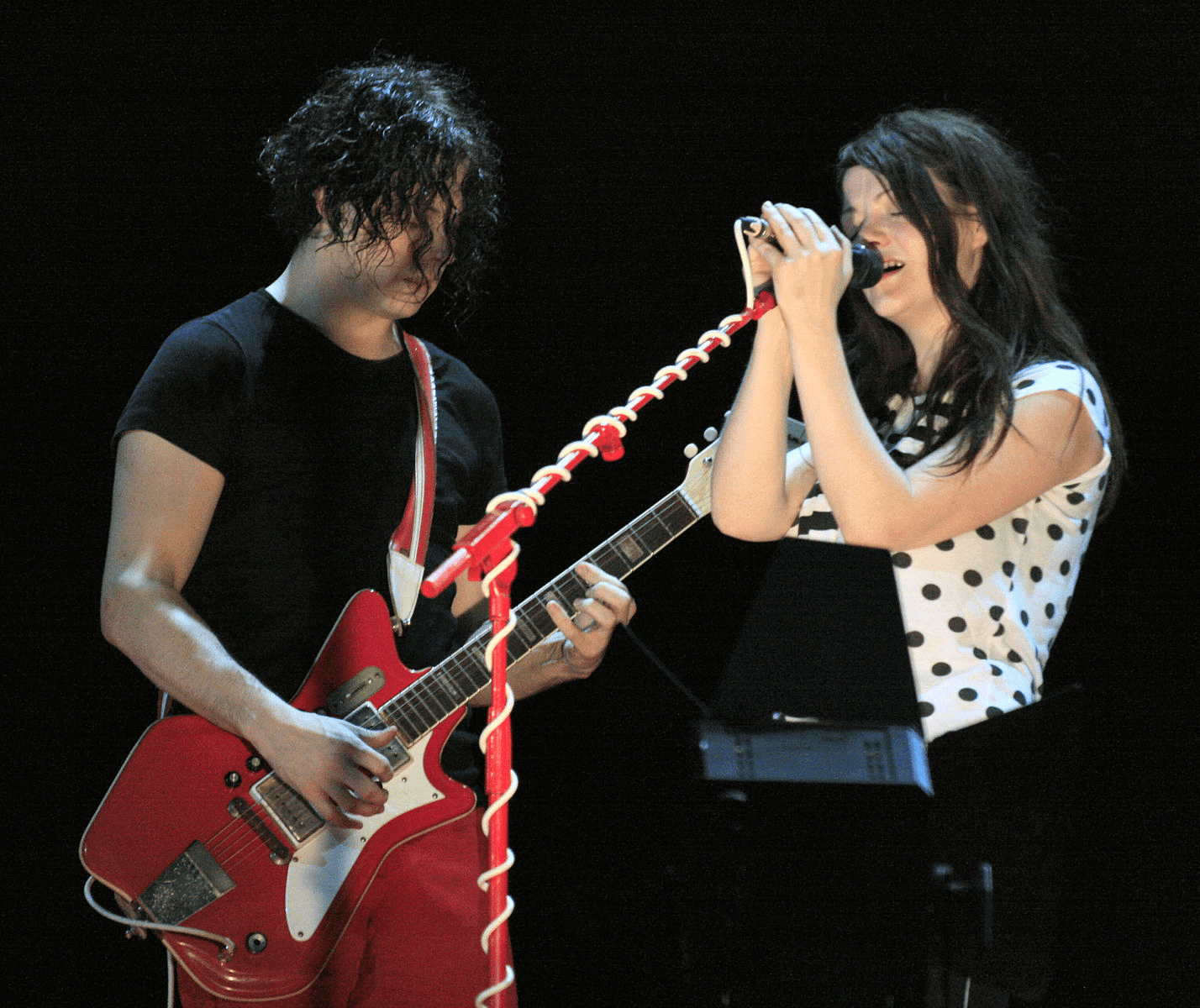

Remaking the Blues: "Death Letter"

In 2000, a band called White Stripes remade this song. Note some similarities and differences with the original:

-

What instruments do you hear?

-

How would you describe the tempo?

-

Can you count the measures of the 12 Bar Blues form?

-

Can you clap along on beats 2 & 4?

-

How would you describe the singer's vocal quality?

-

What is the song about (can you understand the lyrics)?

Attentive and Engaged Listening:

White Stripes, by Fabio Venni, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Flickr.

Learning Checkpoint

- What structural elements and stylistic characteristics of blues music have persisted in other American popular styles?

End of Path 1: Where will you go next?

The Blues in the Church

Path 2

30+ minutes

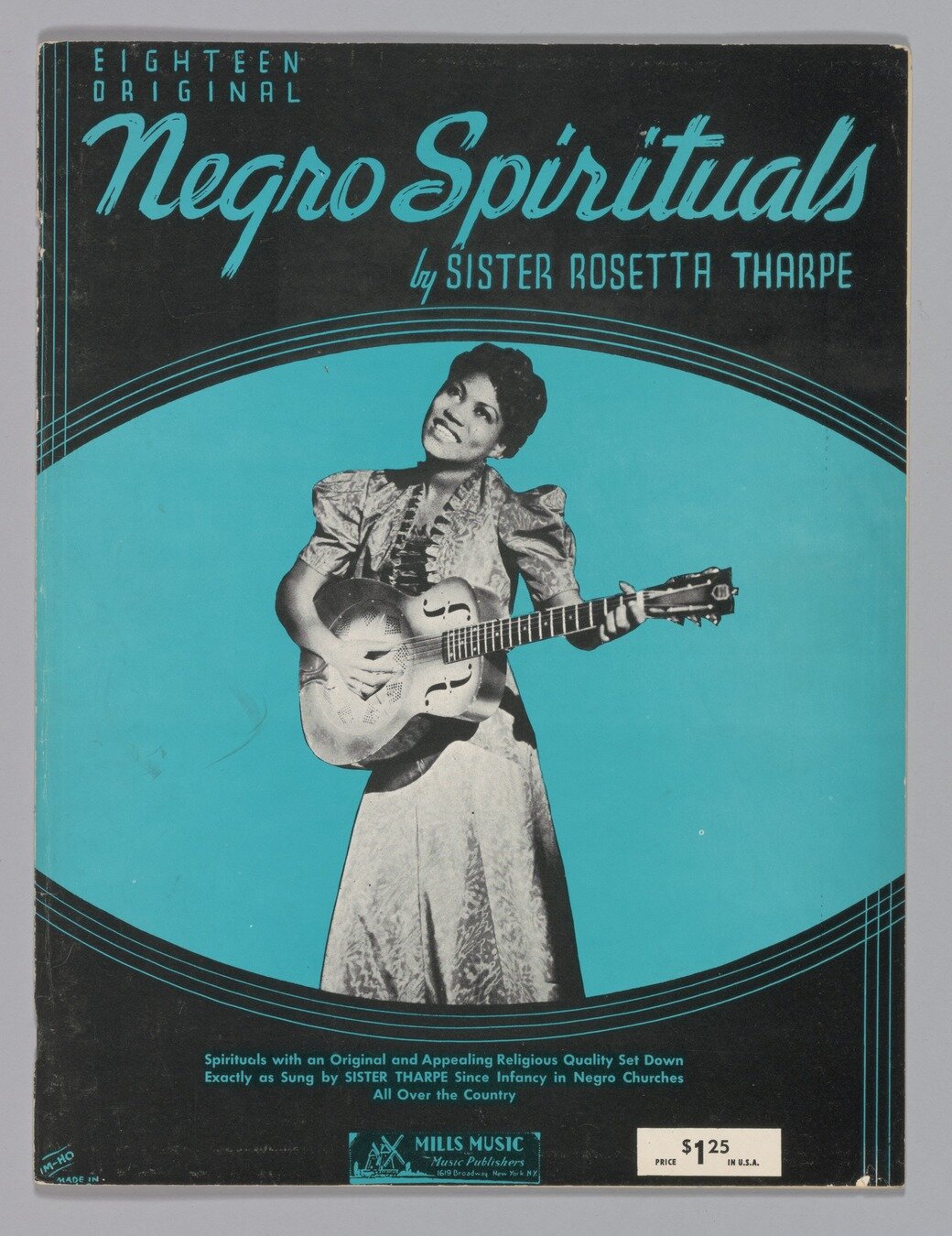

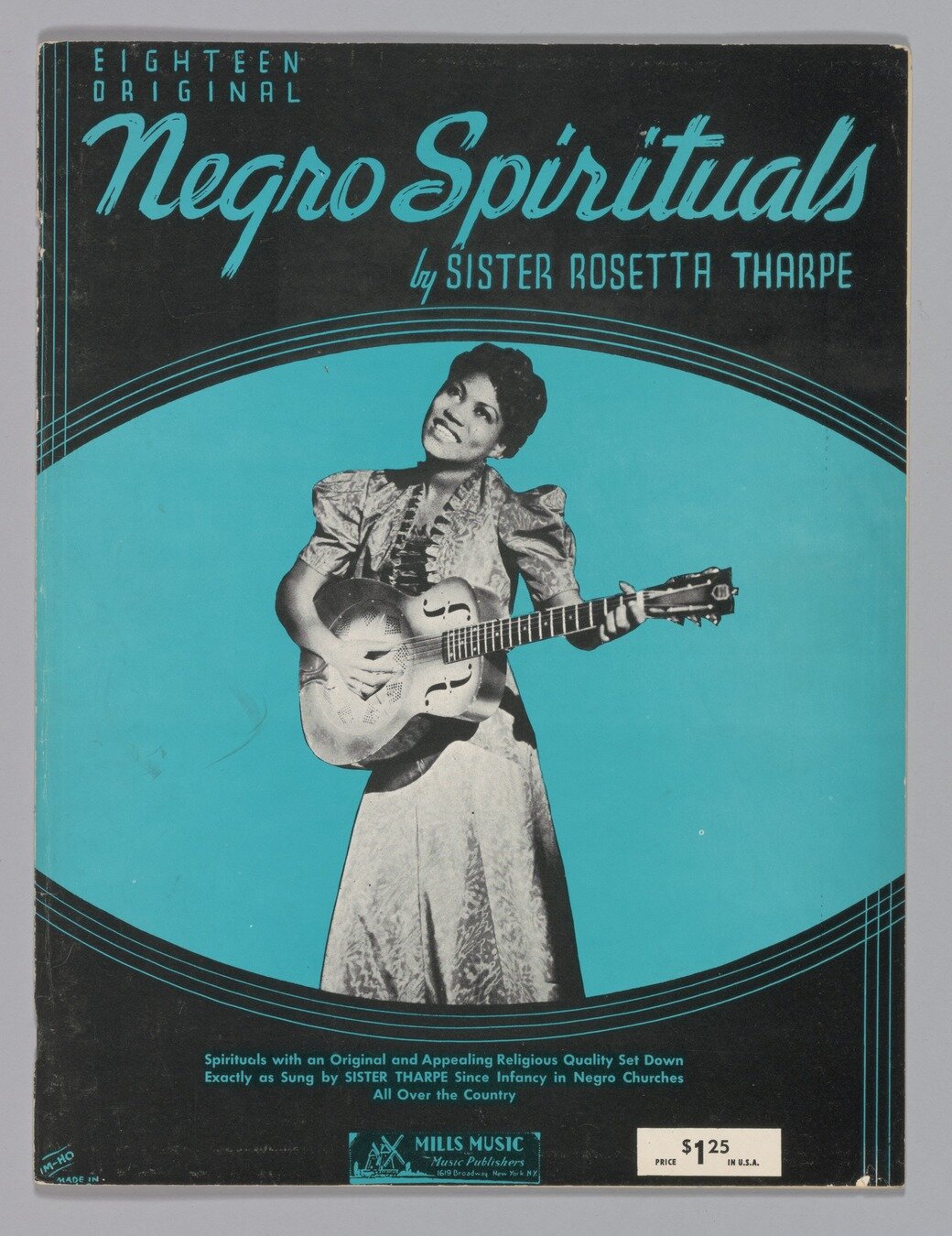

Eighteen Original Negro Spirituals by Sister Rosetta Tharpe, by Mills Music Incorporated. The National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Gospel Music and the Blues

Gospel music began to develop just as blues music was becoming popular across the United States.

Members of the Congregation of the Church of God in Christ, by Gordon Parks. Library of Congress.

"My Work Will Be Done" by The Spiritual Light Gospel Group

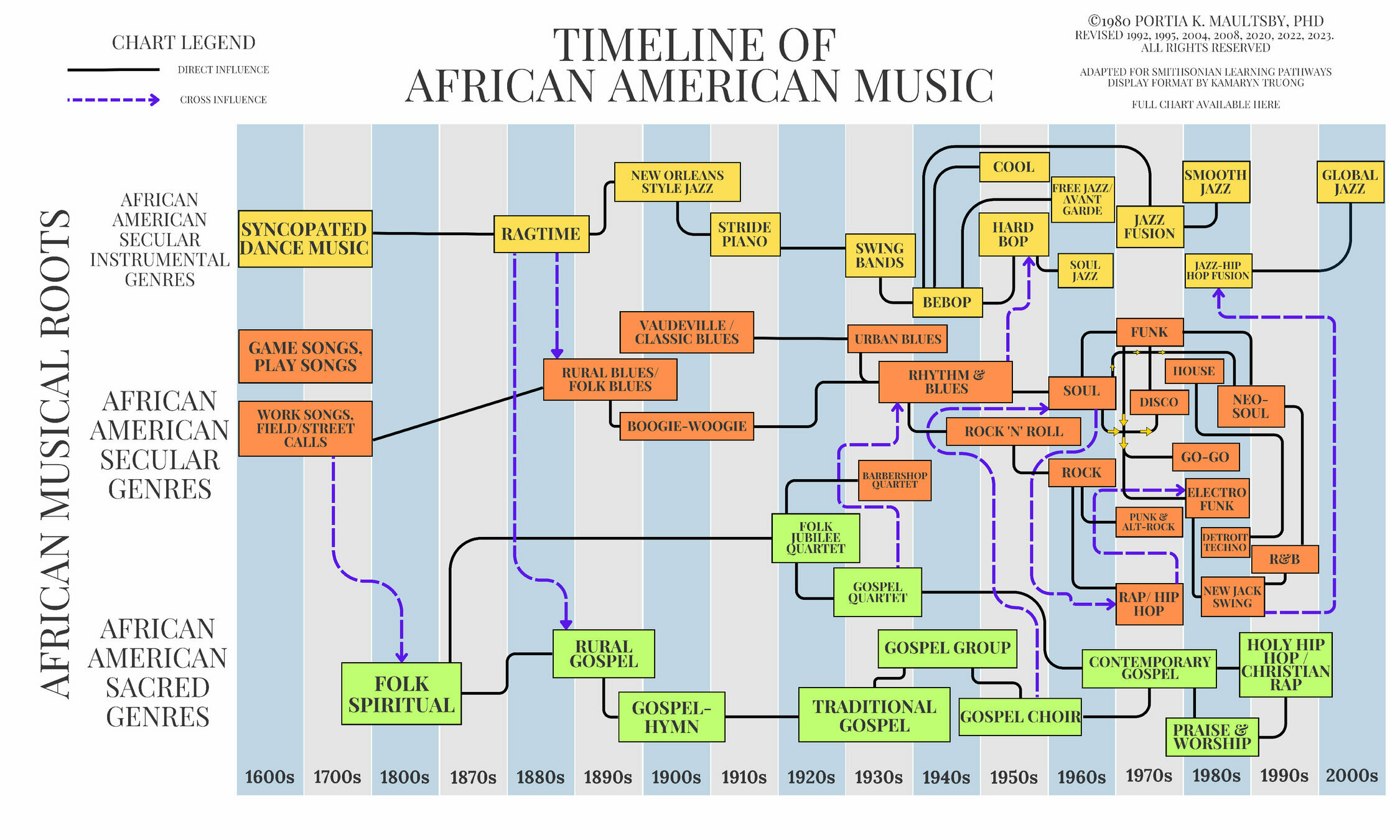

The Evolution of African American Music, by Portia K. Maultsby.

How did gospel music develop?

Gospel music developed from hymns that were sung in church.

Traditional hymns were primarily written in strict 4-part harmony and were often performed in quartets and small ensembles.

Small Village Church, by Bobby Mikul. CCO, via PublicDomainPictures.net.

Do you recognize this traditional hymn?

"Amazing Grace" by the Old Harp Singers of Eastern Tennessee.

Gospel Style

Gospel “style” developed and incorporated certain musical characteristics that were also common in the blues.

Listen to an early gospel song, “I’m Going Over the Hill” performed by Annie Mae McDowell.

Do you notice anything about the performance style that reminds you of the blues?

Classic African American Gospel, cover design by Communication Visual. Smithsonian Folkways Recordings.

Blue Notes

Blue notes are created by raising or flattening the pitch to cause an unexpected, dissonant sound. They do not fit in the diatonic scale.

Blue notes, common in blues music, are also common in gospel music.

"I’m Going Over the Hill" by Fred and Annie Mae McDowell

Listen to an excerpt from this track again . . . This time, raise your hand each time you hear a “blue” note.

Blues Scales

There are scales—called blues scales—that are structured using blue notes.

“Do, Re, Mi, Fa ...

So, La, Ti, Do”

Remember: A scale is a sequence of notes.

You are probably most familiar with the diatonic major scale:

- Do, Re, Mi, Fa, Sol, La, Ti, Do

- 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 1

- C Major: C, D, E, F, G, A, B, C

More Attentive Listening

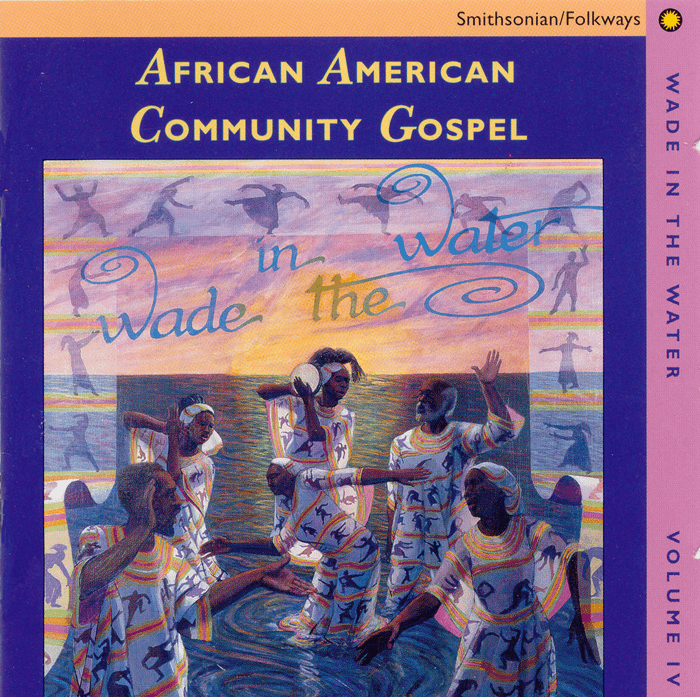

Wade in the Water, Vol. 4: African American Community Gospel, cover art by Joan Wolbier. Smithsonian Folkways Recordings.

Listen another track: The Missionary Quintet singing "Dry Bones: Ezekiel Saw the Wheel”

Do any musical characteristics remind you of the blues?

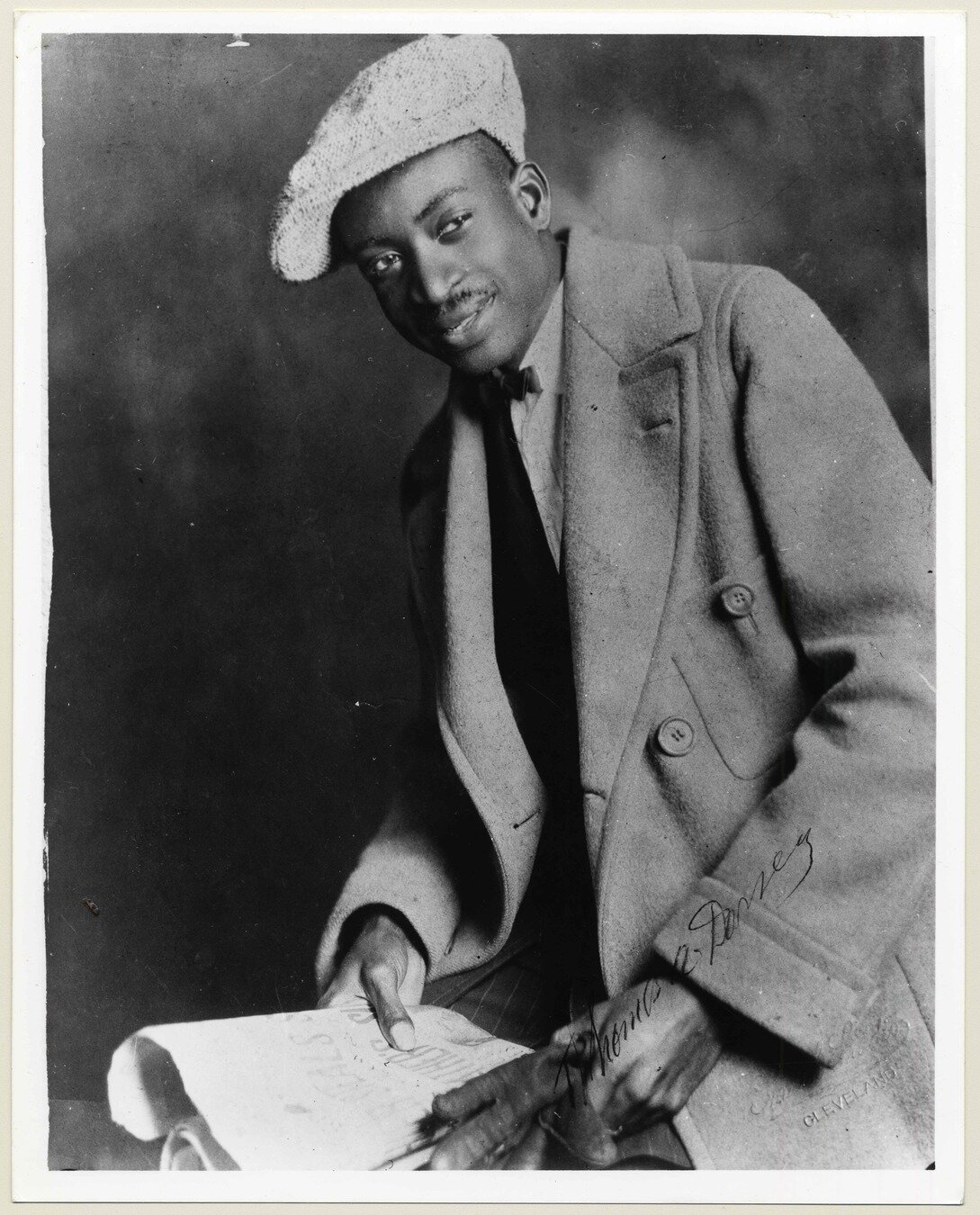

More Context: The Father of Gospel Music

Thomas A. Dorsey, a former blues musician, is often called the "Father of Gospel Music."

Thomas A. Dorsey as Blues Singer Georgia Tom, unknown photographer. National Museum of American History.

The music Dorsey made, which blended sacred text with many musical elements we now associate with the blues, was eventually labeled “gospel.”

"Peace in the Valley" by Thomas A. Dorsey

Generally Speaking .....

The Gospel Blues

It is important to note that the connection between gospel and the blues goes both ways.

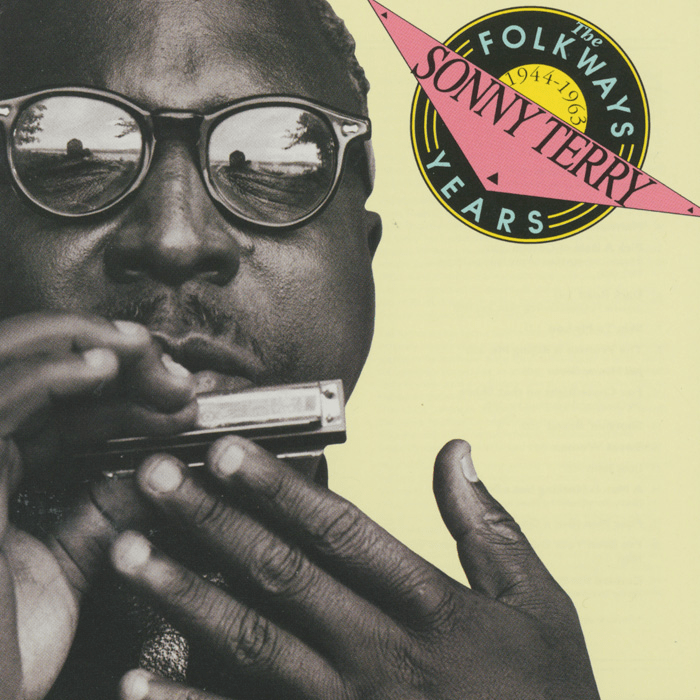

The Folkways Years, 1944-1963, by Carol Hardy. Smithsonian Folkways Recordings.

Just as gospel musicians often incorporate elements of the blues, blues musicians frequently pull from sacred texts.

Listen to this example, by blues musician Sonny Terry:

"Oh What a Beautiful City" by Sonny Terry.

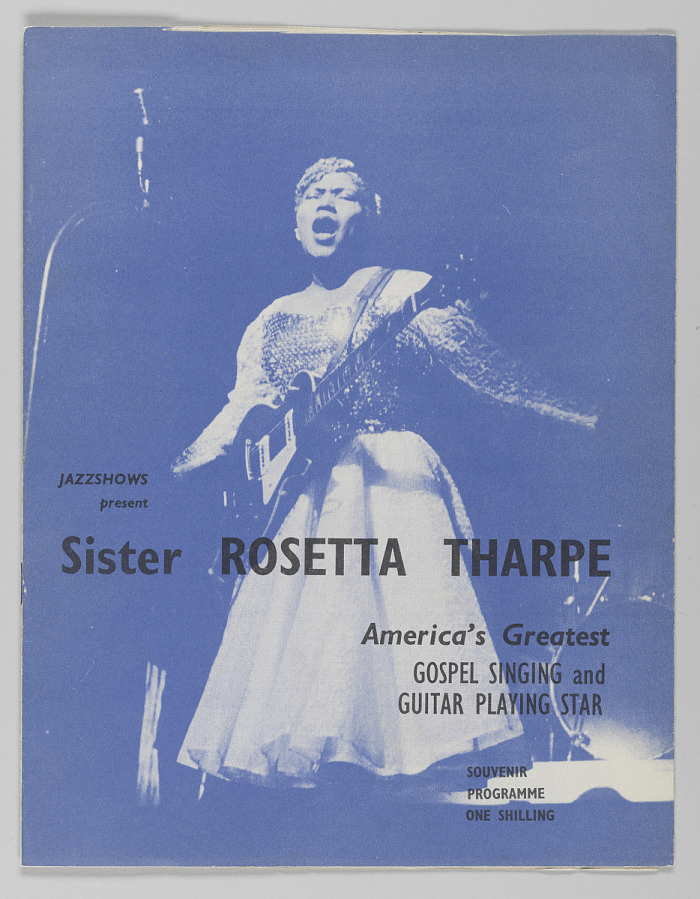

Sister Rosetta Tharpe

Sister Rosetta Tharpe is one of the most well-known female performers to successfully blend the blues with gospel to create a unique gospel blues sound of her own.

Sister Rosetta Tharpe: America's Greatest Gospel Singing and Guitar Playing Star, by Jazzshows Limited. National Museum of African American History and Culture.

"Didn't It Rain" by Sister Rosetta Tharpe and Marie Knight with the Sam Price Trio.

The Godmother of Rock and Roll

Tharpe is often called the "Godmother of Rock and Roll.”

What do you think the term “Godmother” means, used in this context?

Sister Rosetta Tharpe, unknown photographer. National Museum of African American History and Culture.

The Godmother of Rock and Roll

Little Richard

Jerry Lee Lewis

Though her songs had sacred lyrics, Tharpe's performance style and instrumentation drew the appeal of rhythm and blues fans and created an aural precedent for rock 'n' roll artists like Jerry Lee Lewis and Elvis Presley.

She was also key in launching Little Richard's career.

Left: Elvis Presley, by Ralph Wolfe Cowan. National Portrait Gallery. Middle: Jerry Lee Lewis 1950s Publicity Photo, by Maurice Seymour, {{PD US no notice}}, via Wikimedia Commons. Right: Little Richard in 2007, by Anna Bleker, {{PD-user}}, via Wikimedia Commons.

Attentive Listening Activity: The Gospel Blues

Sister Rosetta Tharpe: "Didn't It Rain"

Brother John Sellers: "I'm Coming Back Home to Live with Jesus"

Listen for musical elements and expressive qualities.

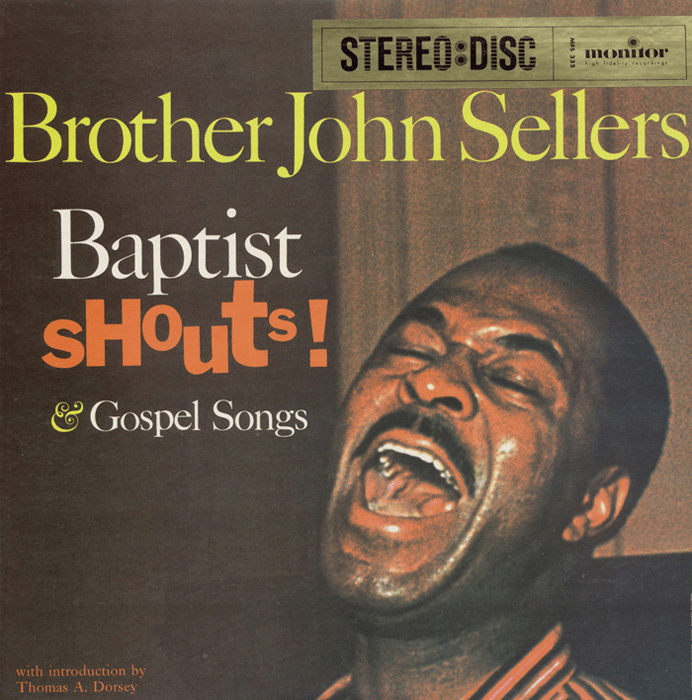

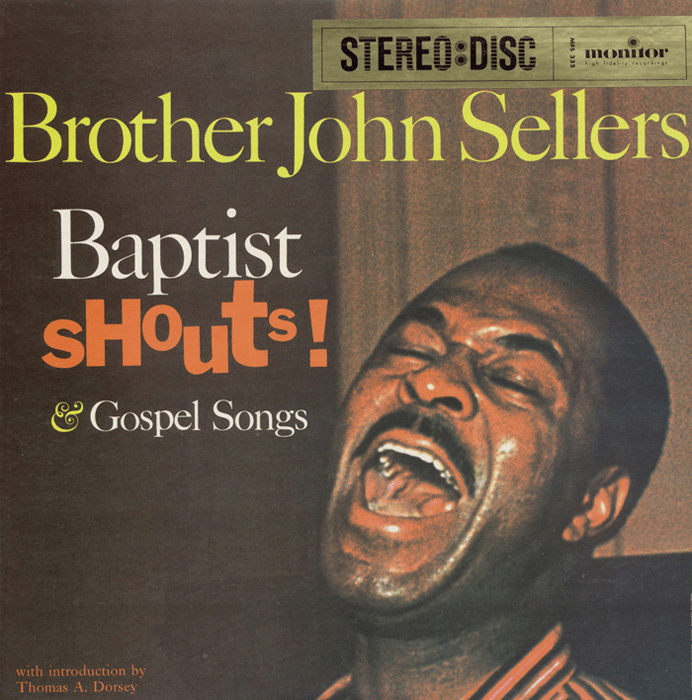

Brother John Sellers ...

Blues and gospel singer John Sellers (often referred to as "Brother John") was discovered by gospel singer Mahalia Jackson when he was just nine years old.

He toured with Jackson during the 1940s and recorded his first solo album in 1954.

Baptist Shouts! & Gospel Songs by Brother John Sellers, by David Chasman. Monitor Records.

Learning Checkpoint

- What are some connections between gospel music and the blues?

- Why is Sister Rosetta Tharpe often called the "Godmother of Rock and Roll"?

End of Path 2: Where will you go next?

From Blues to Hip Hop

Path 3

45+ minutes

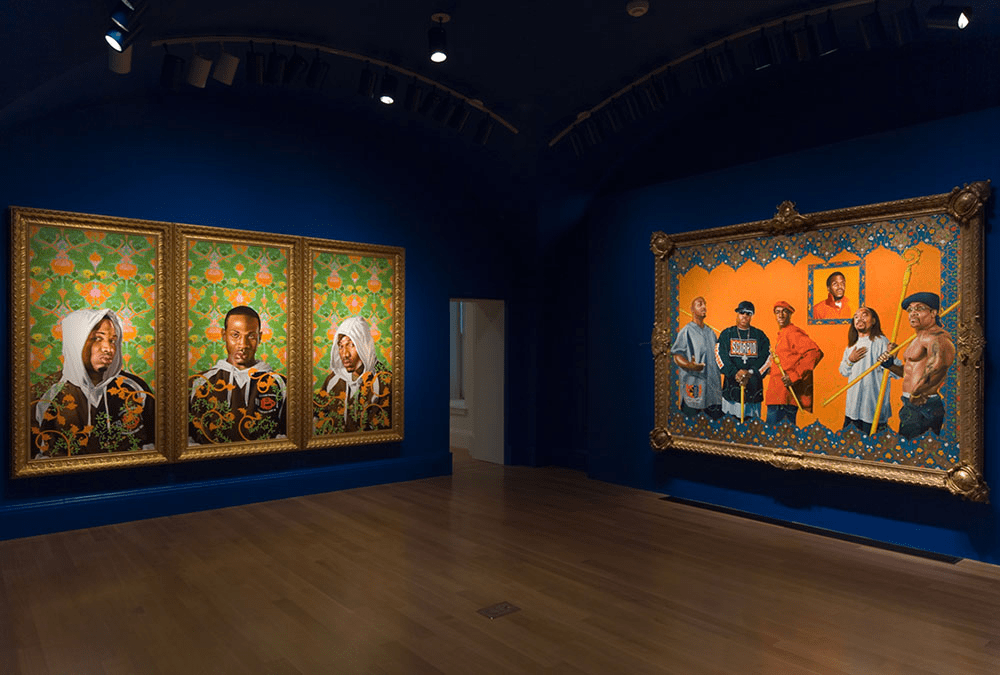

View of "RECOGNIZE! Hip Hop and Contemporary Portraiture," by Mark Gulezian. National Portrait Gallery.

From Blues to Rap

Run DMC & Posse Hollis Queens, photo © Janette Beckman. National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Like the blues, rap music shares a narrative of everyday life.

Rap artists use rhythmic speech (usually over a backing beat or instrumental accompaniment) to tell a story.

Rap is often used to accompany dance, relieve tension in the community, and highlight the skill and new techniques of its performers.

Generally Speaking .....

Deep Roots

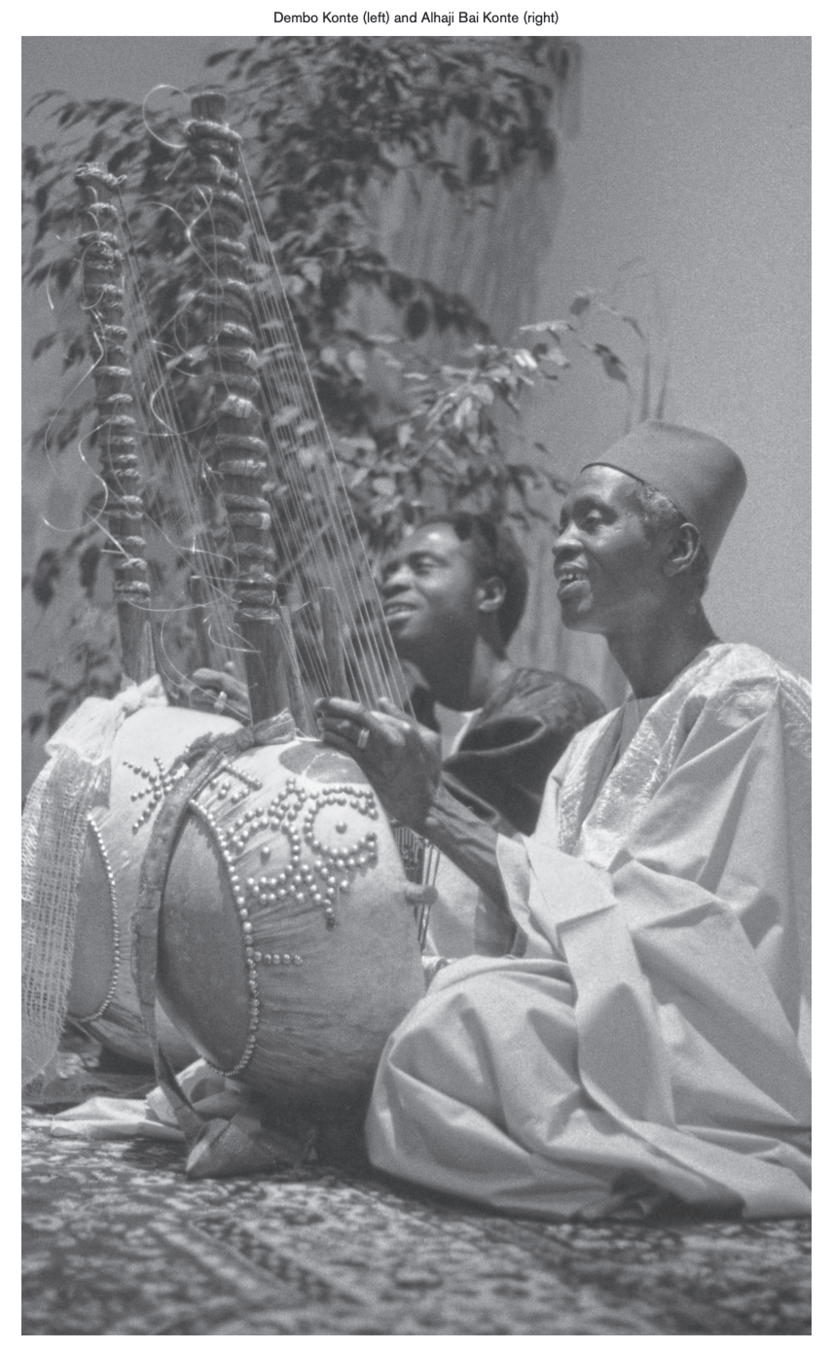

Also like the blues, rap has deep roots in several other African-derived music traditions.

The artists pictured here are griots from The Gambia (West Africa).

Griots Dembo Konte and Alhaji Bai Konte, by Mark and Susan Pevar. Folkways Records.

Griots tell historical narratives (stories) through music.

"Bridging the Gap"

"Bridging the Gap," by Nas and Olu Dara. Lyric video produced by Salaam Remi.

"Bridging the Gap": Lyrical Analysis

What can we learn about connections between the blues and rap by analyzing lyrics from this song?

From the blues, to jazz, to rap. The history of music on this track.

Slaves are harmonizin' them ah's and ooh's.

My poppa was not a rollin' stone ... he been around the world blowin' his horn.

Speak what I want, I don't care what y'all feel.

Did it like Miles and Dizzy, now we gettin' busy.

All those years I've been voicin' my blues.

I come from Mississippi ... ended up in New York City

Reviewing Blues Characteristics

Throughout this Pathway, we have learned about a variety of characteristics that make the “blues” the “blues", related to:

Blues, by Robert Cottingham. Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Form

Style

Lyrics

Instruments

Improvisation

Pitches

Time

"Bridging the Gap": Musical Analysis

As you listen to "Bridging the Gap" again, think about these common characteristics of blues music:

- Form

- Style

- Lyrics

- Instrumentation

- Improvisation

- Pitches

- Time

Are any of these blues elements present in this recording?

Rap and Hip Hop Culture

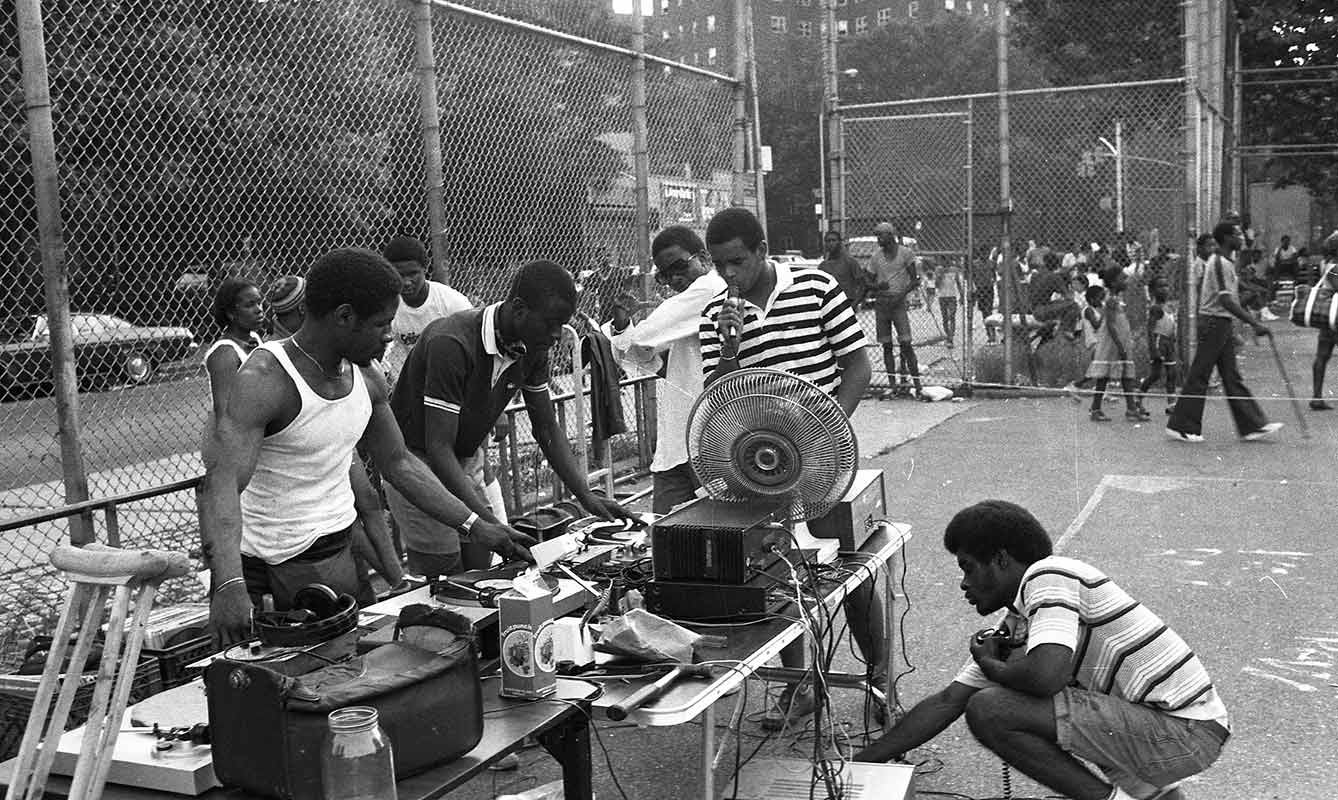

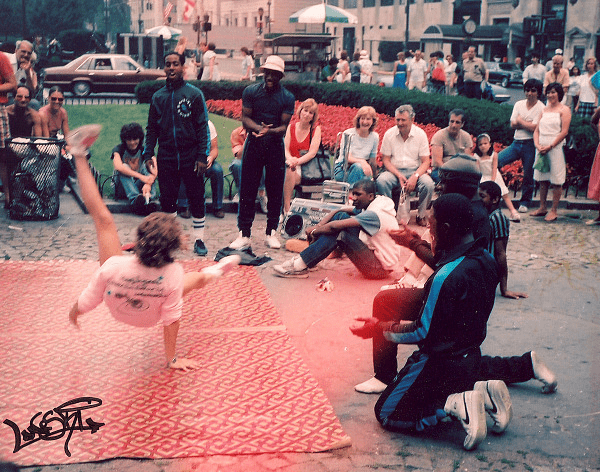

Rap is just one component of Hip Hop culture, which was born out of communities experiencing difficult times in the Bronx (New York) in the 1970s and 1980s.

G Man - Park Jam In The Bronx, by Henry Chalfant. Courtesy of the Artist.

Four Pillars of Hip Hop

Handling of beats and music using record players, turntables, and DJ mixers

Writings, drawings, or paintings made on surfaces in public places ... also known as “graf” or “writing”

DJing

MCing (aka Rapping)

Putting spoken-word poetry to a beat ... a rhythmic rhyming style

Graffiti Painting

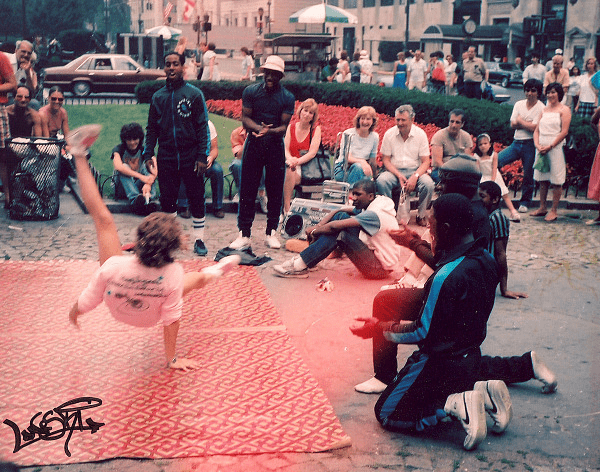

Break Dancing

A form of dance that also encompasses an overall attitude and style

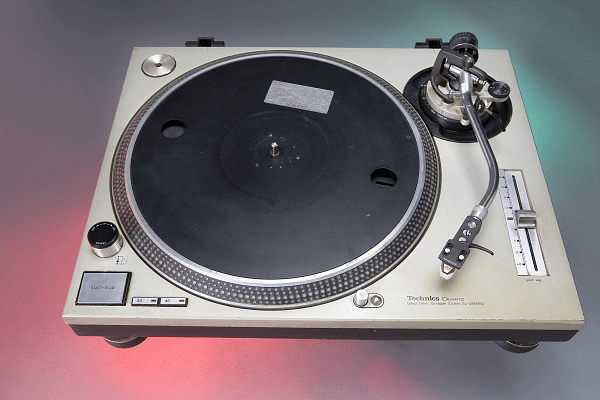

DJ

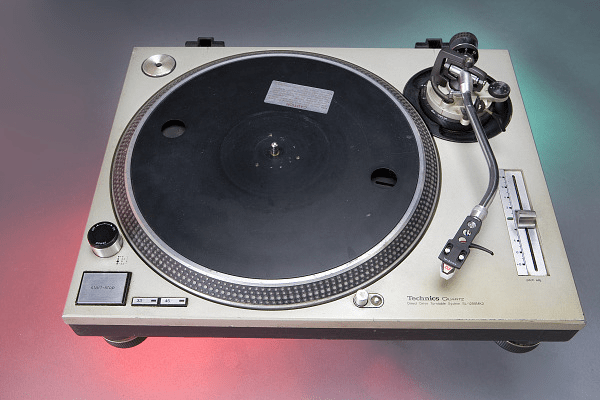

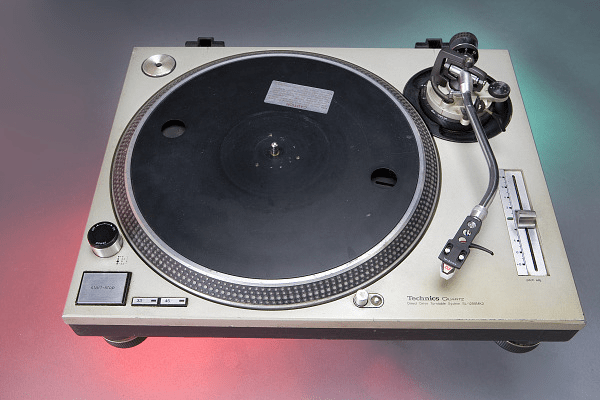

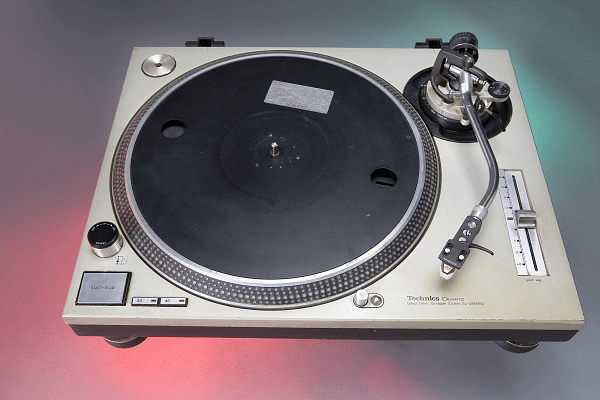

Above: Technics Turntable, Used By Grandmaster Flash, by Technics. National Museum of American History.

Left: Grandmaster Flash, by Ernie Paniccioli. Cornell University Library.

The DJ (Disc Jockey) prepares the beat and music for the audience, rapper/mc and break dancers.

MC / Rapper

An MC (master of ceremonies) or rapper is responsible for delivering a vocal performance (usually rhythmic) over a beat or musical accompaniment.

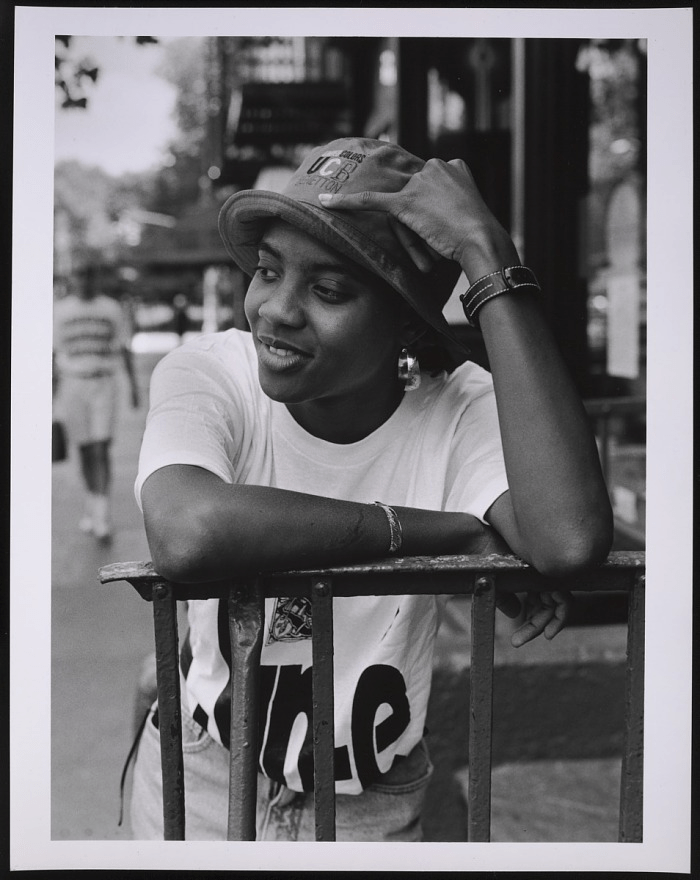

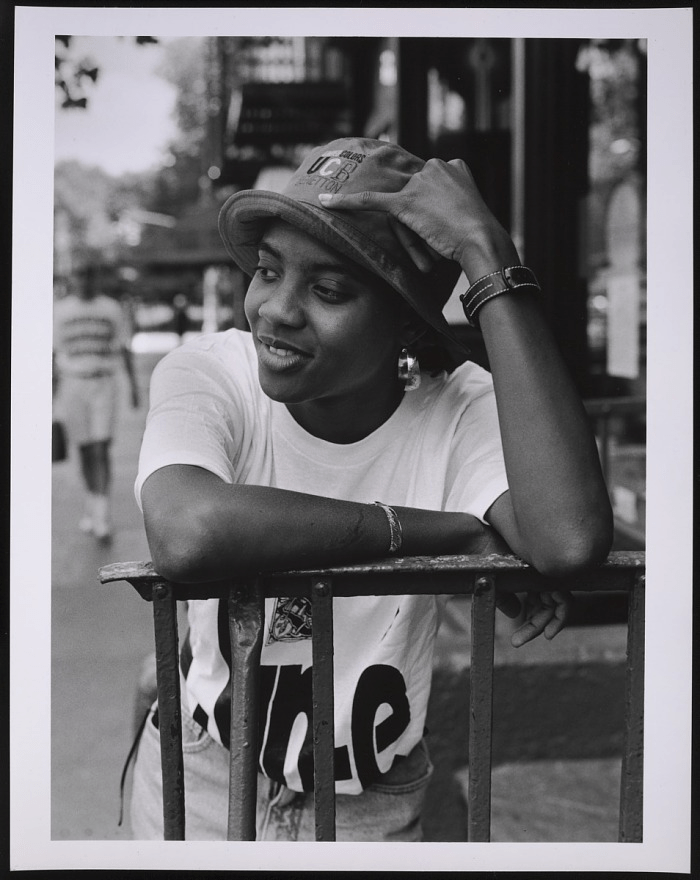

Above: MC Lyte on Manhattan's Lower East Side, by Al Pereira and Bill Adler. National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Left: Female Rappers, Class of '88, photo © Janette Beckman. National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Break Dancer

Breakdancing is a style of street dancing that is typically set to the breaks in songs.

B-Girl Laneski, unknown photographer. National Museum of American History.

Graffiti Artist

Graffiti is an artform used to tell a visual story.

Left: Artist at Work, by Tee Cee, CC BY 2.0, via Flickr. Right: Graffiti Street Artist, by Professor Bop, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0, via Flicker.

Generally Speaking .....

Creative Activity

In this culminating activity, students will collaboratively create a performance that blends two worlds—blues and hip hop.

Run DMC & Posse Hollis Queens, photo © Janette Beckman. National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Muddy Waters, by John Wesley Work III. Middle Tennessee University.

Hip Hop Meets the Blues: Getting Started

Form groups of four people.

Choose an overarching topic for your composition

(something that relates to the blues generally, and the Women in Blues pathway specifically).

Keeping your topic in mind, write lyrics that tell a story.

Hip Hop Meets the Blues: Choosing Group Roles

Each student in the group will then choose to represent one of the four pillars of hip hop.

DJ

Break Dancer

Graffiti Artist

MC / Rapper

- You will provide the underlying beat/accompaniment.

-

You can do this in a variety of ways:

- Use loops to create a "beat".

- Beatboxing

- Create a riff (ostinato) and play it on an instrument.

-

You will create a visual representation of your story:

- Through a drawing, painting, collage, sculpture, mural, etc.).

DJ

MC / Rapper

-

You will work closely with the DJ.

- Ultimately you will narrate the story by reciting the lyrics to the rhythm they create.

Graffiti Painter

Break Dancer

-

You will interpret the story through movement.

- You can choose any dance form ... it doesn’t have to be break dancing!

About the Group Roles

Share Your Work!

Silhouettes of Expressive Dance Group, ID 316836201, © Rebuz777 | Dreamstime.com.

Want to learn more about the history of hip hop?

Smithsonian Anthology of Hip Hop and Rap, cover design by Cey Adams. Smithsonian Folkways Recordings.

Check out the Smithsonian Anthology of Hip Hop and Rap, a collaboration between Smithsonian Folkways Recordings and the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

This boxed set, which includes 129 tracks on 9 CDs and a 300–page book, chronicles the growth of the music and culture from the parks of the Bronx to solidifying a reach that spans the globe.

Learning Checkpoint

- What are some connections between the blues and rap / hip hop?

- How does each pillar of hip hop contribute to hip hop culture?

End of Path 3 and Lesson 12: Where will you go next?

Lesson 12 Media Credits

Audio courtesy of

Smithsonian Folkways Recordings

Images courtesy of

Smithsonian Folkways Recordings

Smithsonian American Art Museum

National Museum of African American History and Culture

National Museum of American History

Library of Congress

National Portrait Gallery

The Center for Popular Music, Middle Tennessee University

Cornell University Library Digital Collections

National Museum of American History

Jim Marshall Photography LLC

Henry Chalfant

Portia K. Maultsby

© 2022 Smithsonian Institution. Personal, educational, and non-commercial uses allowed; commercial rights reserved. See Smithsonian terms of use for more information.

This Lesson was funded in part by the Grammy Museum Grant and the Smithsonian Youth Access Grants Program, with support from the Society for Ethnomusicology and the National Association for Music Education.

For full bibliography and media credits, see Lesson 12 landing page.