Listen What I Gotta Say: Women in the Blues

Lesson Hub 8

Intersections of Race and Class in the Blues

6th grade–8th grade

How did the intersection between race and class affect how blues music was marketed, perceived, and advertised?

Chirpin' the Blues, by Jack Mills Inc. National Museum of American History.

The question to consider in this lesson is . . .

The Intersection of Race and Class in the Blues

30+ MIN

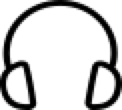

Selling the Blues: The Emergence of Race Records

Component 1

30+ minutes

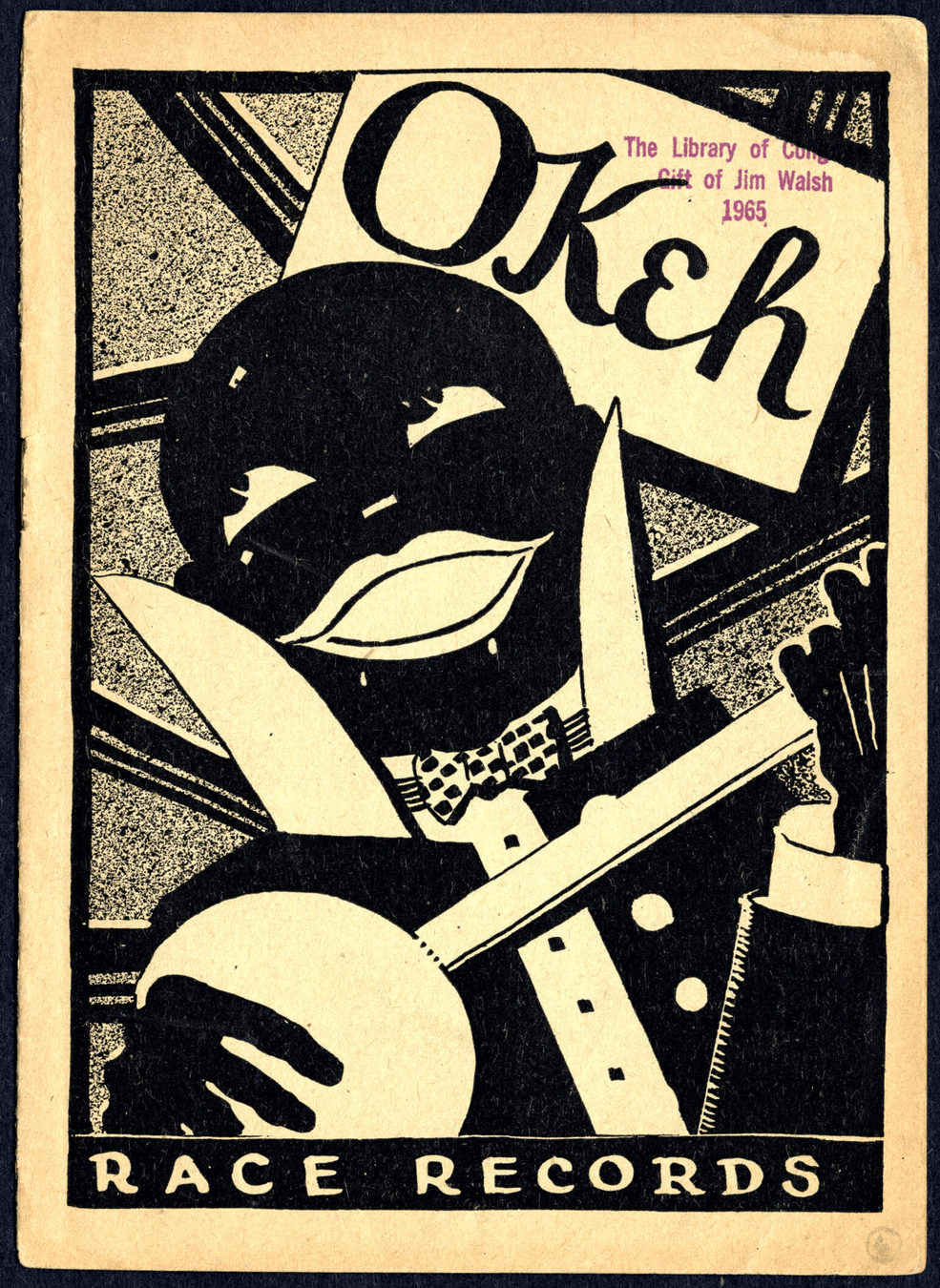

Okeh Race Records Form No. 2566, by the Okeh Phonograph Corporation. Library of Congress.

Think of your favorite song ...

Share the song, artist, or genre with the group.

What do you like most about it?

Vocal timbre/quality?

Instrumentation?

Rhythmic feel?

Simple melody?

Connection to lyrics?

Childhood memory?

Family tradition?

Something else?

Netsky (DJ), by James Starkey, CC-BY-2.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Take a moment to reflect ...

What memory popped into your mind first?

If stranded on an island with only one album, would you select this song, artist(s), or genre?

What is something you appreciate about this song?

Contemplate the memories attached.

Hum the first few lines of the song you chose silently.

Are they good or bad?

Now ponder ...

How you would feel if the song, artist, or genre that you cherish and love dearly was never available for sale?

The only time that you could listen to it is if you went to the artist's live concert or performed it at home with friends and family or by yourself.

There is other music available that you can listen to on Spotify, iTunes, YouTube, etc., but there are no record labels that produce the music that you love.

?

?

Did you know?

This was the case for many African Americans in the early 20th century.

Nearly 50 years after the Civil War, marketing companies (including the music industry) still did not make products with African American buyers in mind.

Discussion

Why do you think companies did not market music and other products toward African Americans?

Discrimination?

Exclusion?

Unawareness?

Lack of expendable income?

???

Activity

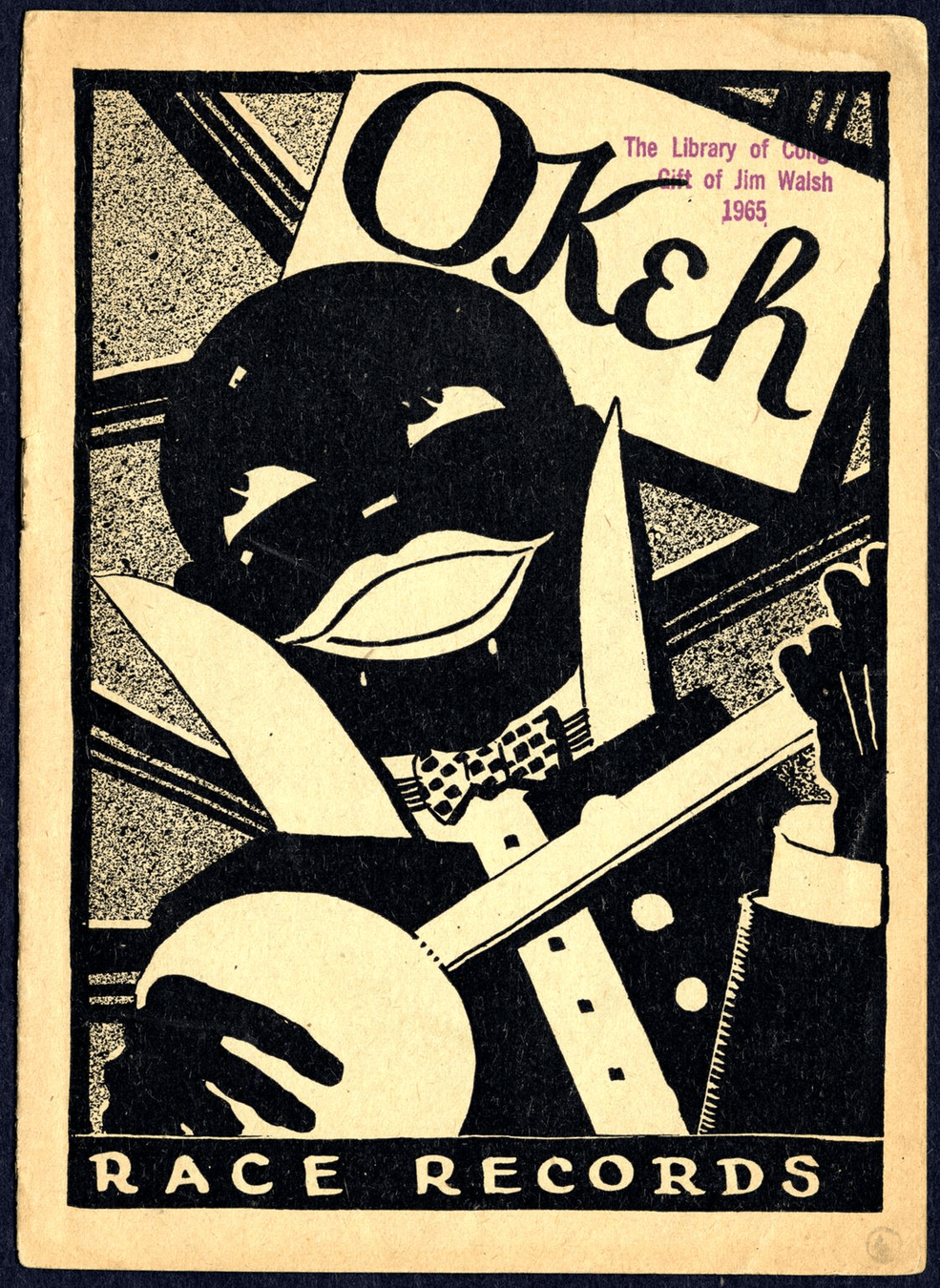

Who did marketing companies target during this time?

In the next activity, you will analyze several advertisements.

While viewing each image, ask yourself:

- Who is the intended audience?

- Who is this excluding?

- Who might this be offending?

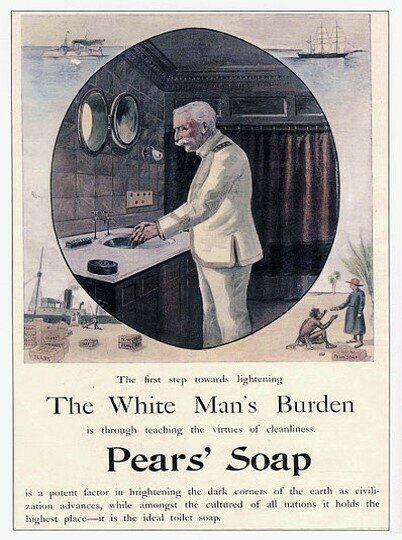

Example 1: Pear Soap, 1890

- Who is the intended audience?

- Who is this excluding?

- Who might this be offending?

Pears' Soap, unknown artist, {{PD-US-expired}}, via Wikimedia Commons.

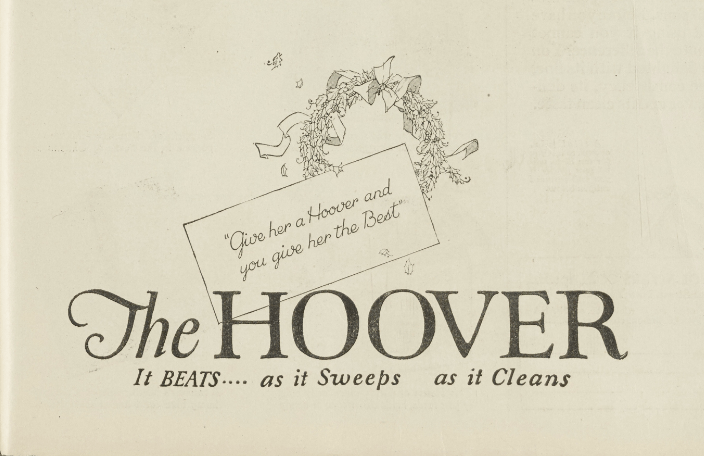

Example 2: Hoover Vacuum Cleaners, 1924

Who is the intended audience?

The Hoover, by The Hoover Company, {{PD-US-expired}}, via Cornell University Library Digital Collections.

Who is this excluding?

Who might this be offending?

Generally Speaking .....

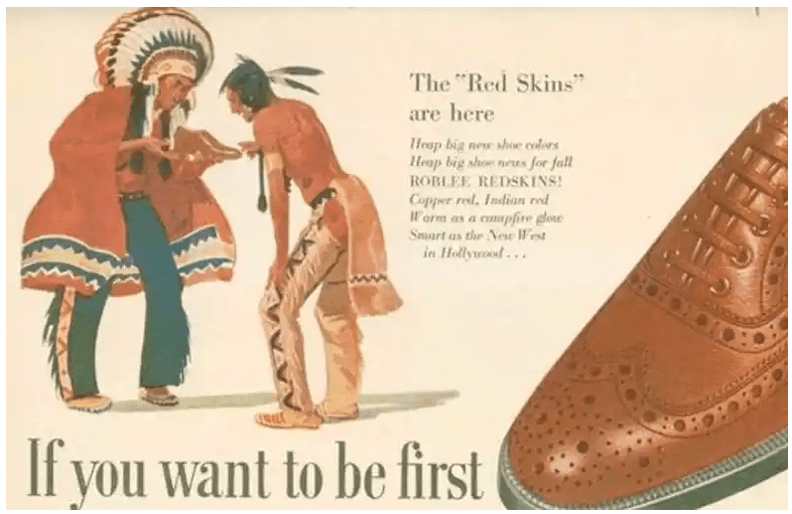

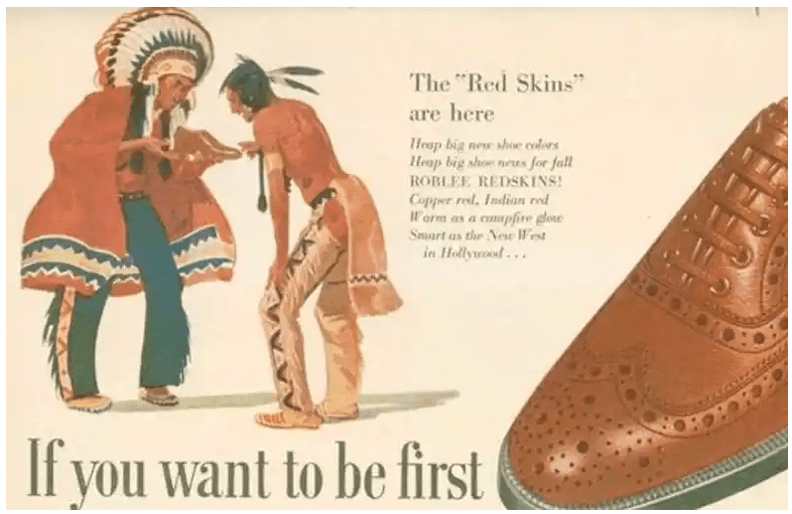

Example 3: Roblee Redskin Shoes, 1940

Roblee Redskin Shoes, by Roblee Shoes. ANA Educational Foundation.

- Who is the intended audience?

- Who is this excluding?

- Who might this be offending?

Example 4: Van Heusen Ties, 1951

Listen for these common musical characteristics in blues music . . .

Where do you think these characteristics came from?

Show Her It's a Man's World - Van Heusen Ties, by the Philips-Jones Corp, PD, via Flickr.

- Who is the intended audience?

- Who is this excluding?

- Who might this be offending?

Target Audience: White Men

Why do you think the “target audience” for so many products in the early to mid 20th century was white men?

Do you think this target audience wanted to buy blues albums? Why or why not?

Even today ...

... we can find examples of commercials, advertisements, and marketing campaigns that target white male audiences (or are blatantly racist).

However, these trends did begin to change somewhat as the 20th century progressed.

Why?

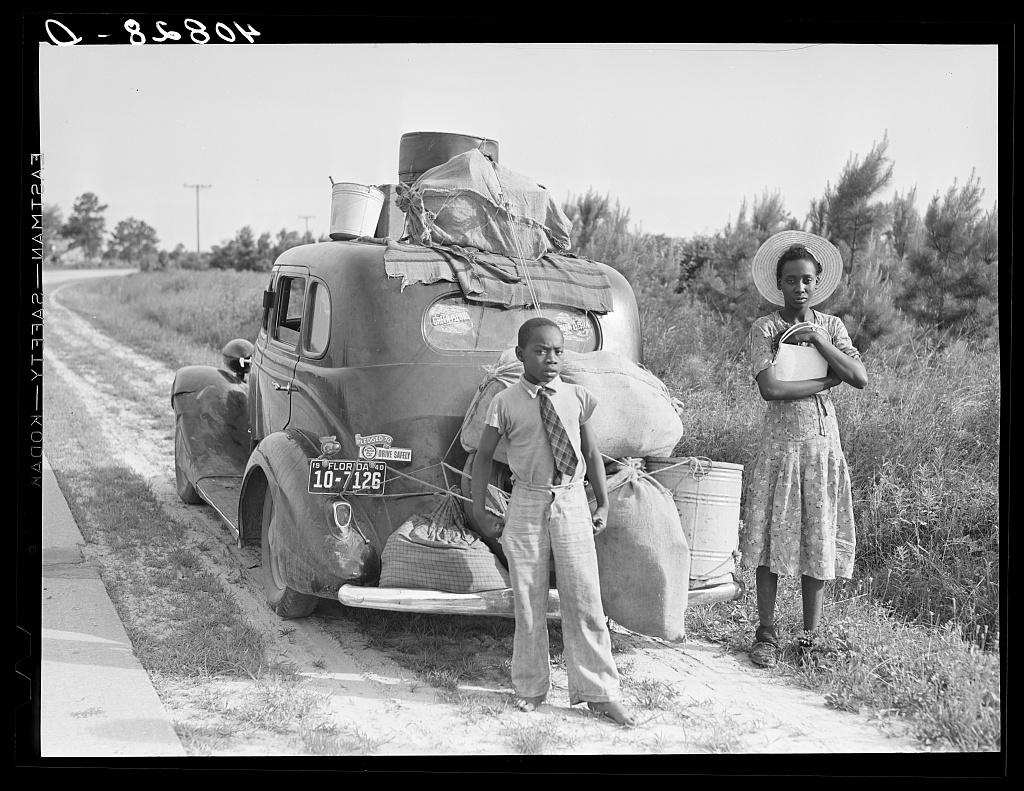

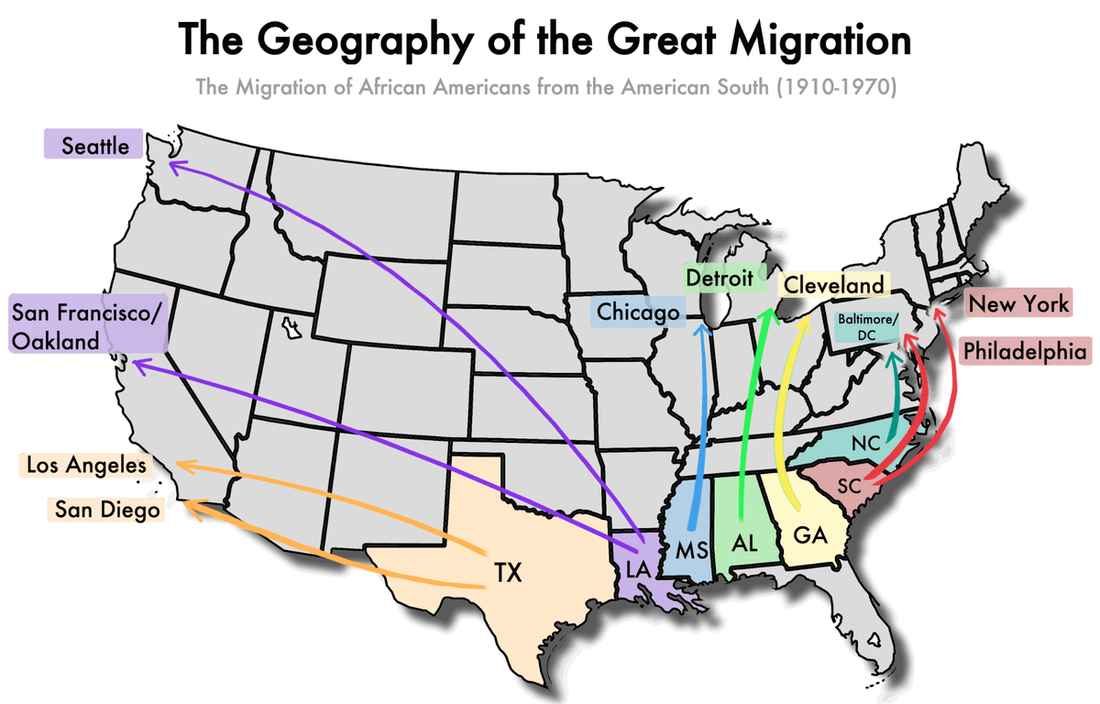

The Great Migration

At the turn of the 20th century, many African Americans migrated to northern urban centers (Chicago, St. Louis, DC, Harlem, Detroit, etc.)—this was called the Great Migration.

This shift in class finally allowed them to have expendable income to purchase non-essential items, like records.

In those cities, African Americans found better paying jobs, making them working class.

Group of Florida Migrants on Their Way to Cranberry, New Jersey, to Pick Potatoes. Near Shawboro, by Jack Delano. Library of Congress.

The Geography of the Great Migration, unknown artist. Priceonomics.

"Crazy Blues"

Listen to this historic recording!

Prior to Mamie Smith recording the song "Crazy Blues" in 1920, there were no African American vocal recordings of blues music.

Mamie Smith, unknown photographer. {{PD-old-70}}, via Wikimedia Commons.

But does it sell?

Mamie Smith Okeh Records Advertisement, Okeh Records, {{PD-US-expired}}, via Jazz Dirgisi.

The Blues Experiences Commercial Success

Mamie Smith's “Crazy Blues” was a huge hit, reportedly selling over 75,000 in its first few months of release.

The success of “Crazy Blues” indicated there was indeed a growing market for "Black" music (such as the blues).

This success also showed record labels that African Americans were consumers with buying power.

Mamie Smith and Her Jazz Hounds, unknown artist, {{PD-US-expired}}, via Medium.

Generally Speaking .....

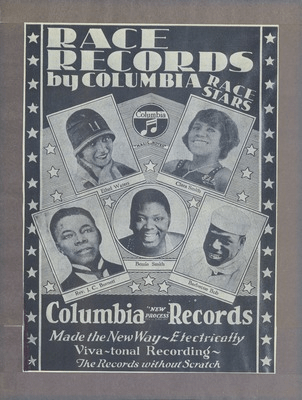

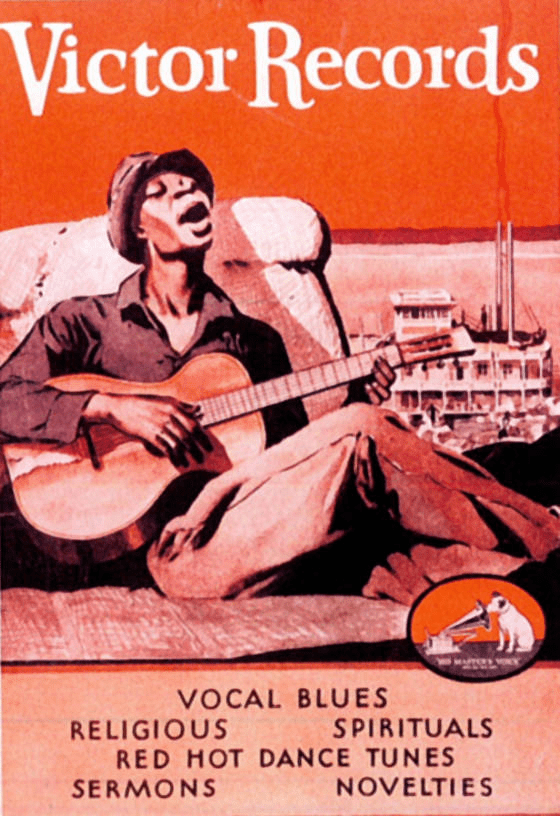

Race Records

Due to increasing demand, more popular record labels began to produce recordings made by African American artists, intended for African American audiences.

These sound recordings (78-rpm phonograph records) became known as "race records."

Race Records by Columbia, by Columbia Records. The University of Mississippi Libraries.

Generally Speaking .....

Race Records

The name “Race Records” indicated the audience for whom the recordings were intended.

Race records were marketed to African Americans between the 1920s and 1940s.

Victor Records "Race Records" Catalog, by Victor Talking Machine Company, {{PD-US-not renewed}}, via Wikimedia Commons.

They encompassed various African-American musical genres, including blues, jazz, and gospel music (also comedy).

Legacies of Race Records

The success of the race records market helped to facilitate the rise of Black-owned record companies.

Additionally, these recordings are living historical artifacts . . . they have been influential for many artists and have informed the development of many American popular music styles.

Learning Checkpoint

- What were “race records” and why are they an important part of the history of African American music (in particular, the blues)?

End of Path 1: Where will you go next?

The Harlem Renaissance and the Blues

Path 2

30+ minutes

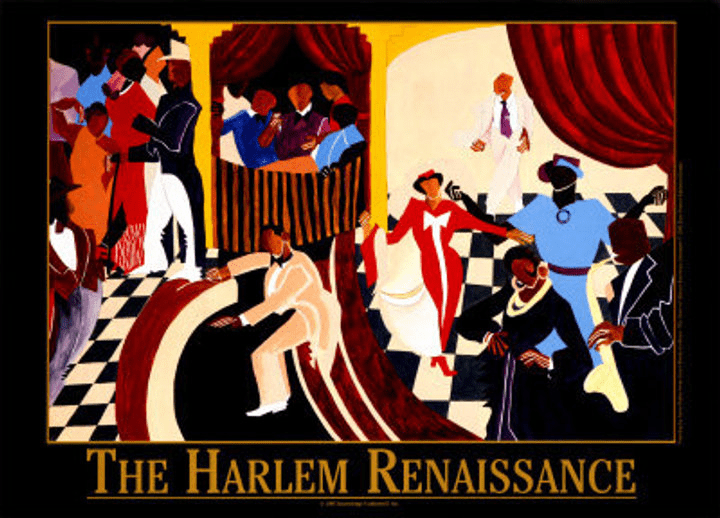

The Harlem Renaissance, by Jerry Butler. Courtesy of the artist.

Creating a New Narrative

The Harlem Renaissance (1910s-1930s) was a golden age in African American culture.

During this time, Harlem, NYC became a central hub for Black arts, music, literature, and theatre.

The classic blues was simultaneously developing during this time (1920-1929).

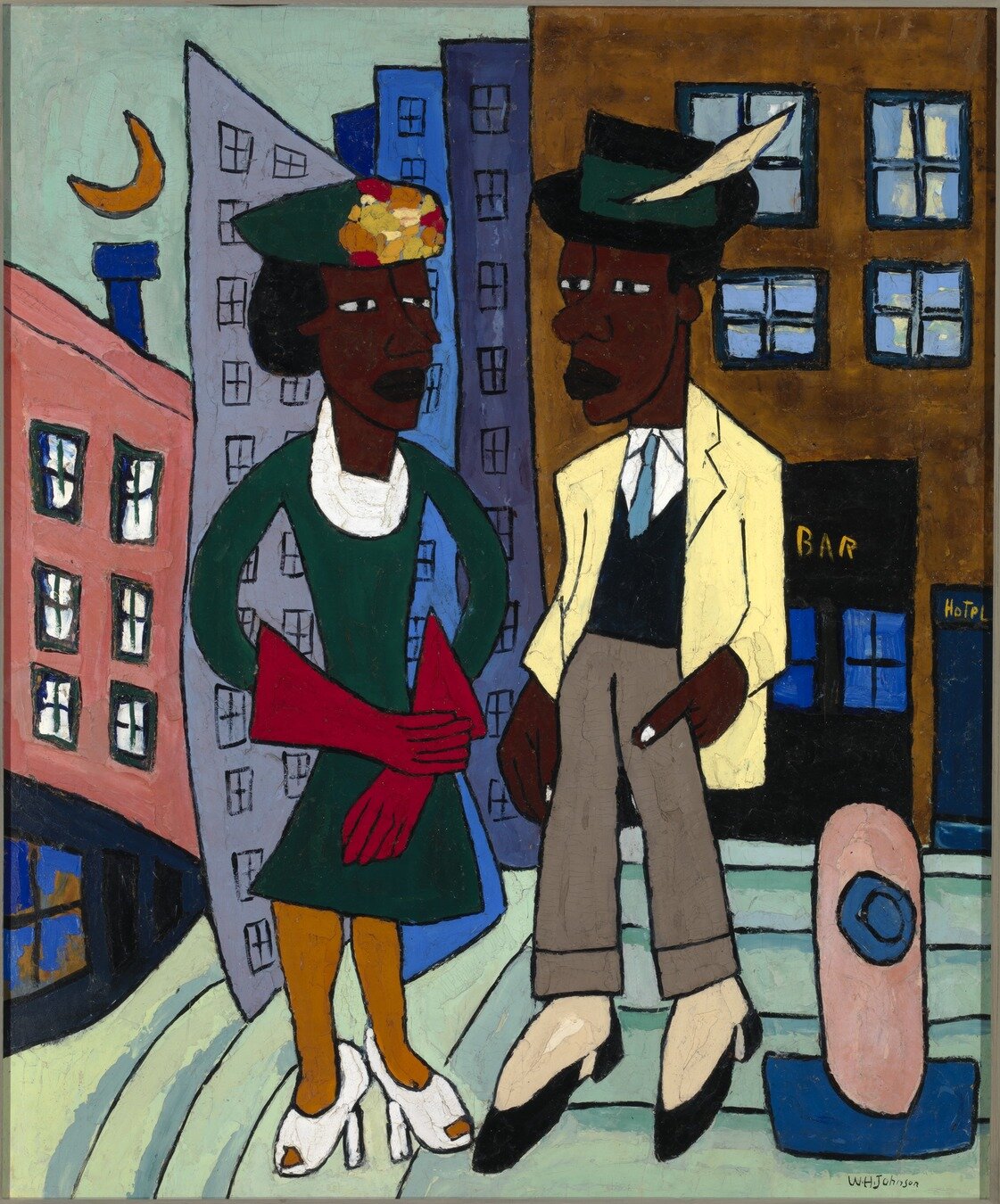

Street Life, Harlem, by William H. Johnson. Smithsonian American Art Museum.

The Harlem Renaissance

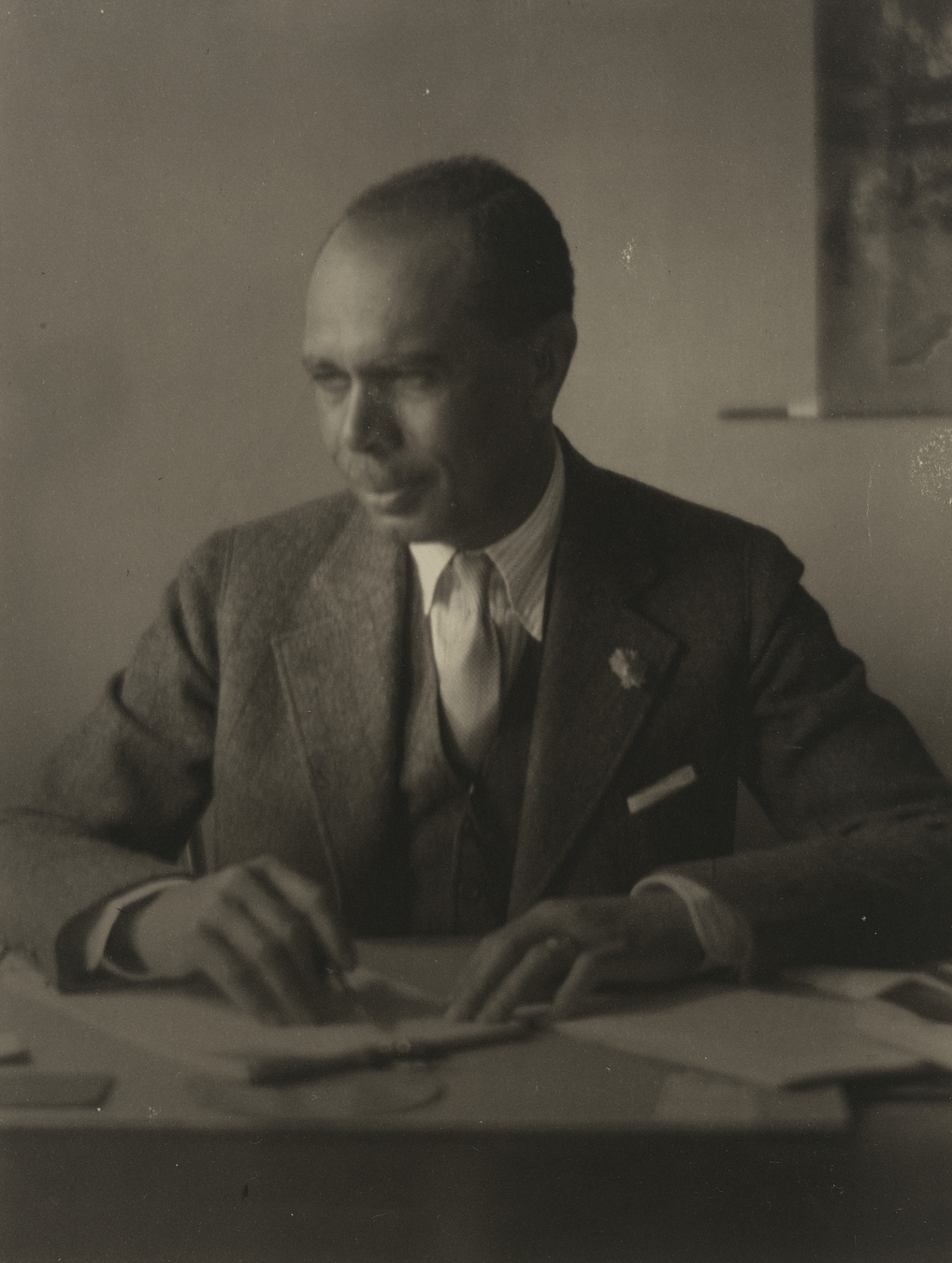

Alain LeRoy Locke, by Alfred Eisenstaedt, {{PD-US-no notice}}, via Wikimedia Commons.

The Harlem Renaissance was an intellectual, social, and artistic explosion.

At the time, it was known as the "New Negro Movement," named after “The New Negro,” a 1925 anthology edited by American writer Alain Locke (pictured here).

Watch this short video...

...to learn more about the Harlem Renaissance.

Here at the Smithsonian: The Harlem Renaissance, by the Smithsonian Office of Telecommunications. Smithsonian Institution Archives.

Generally Speaking .....

Class and Music

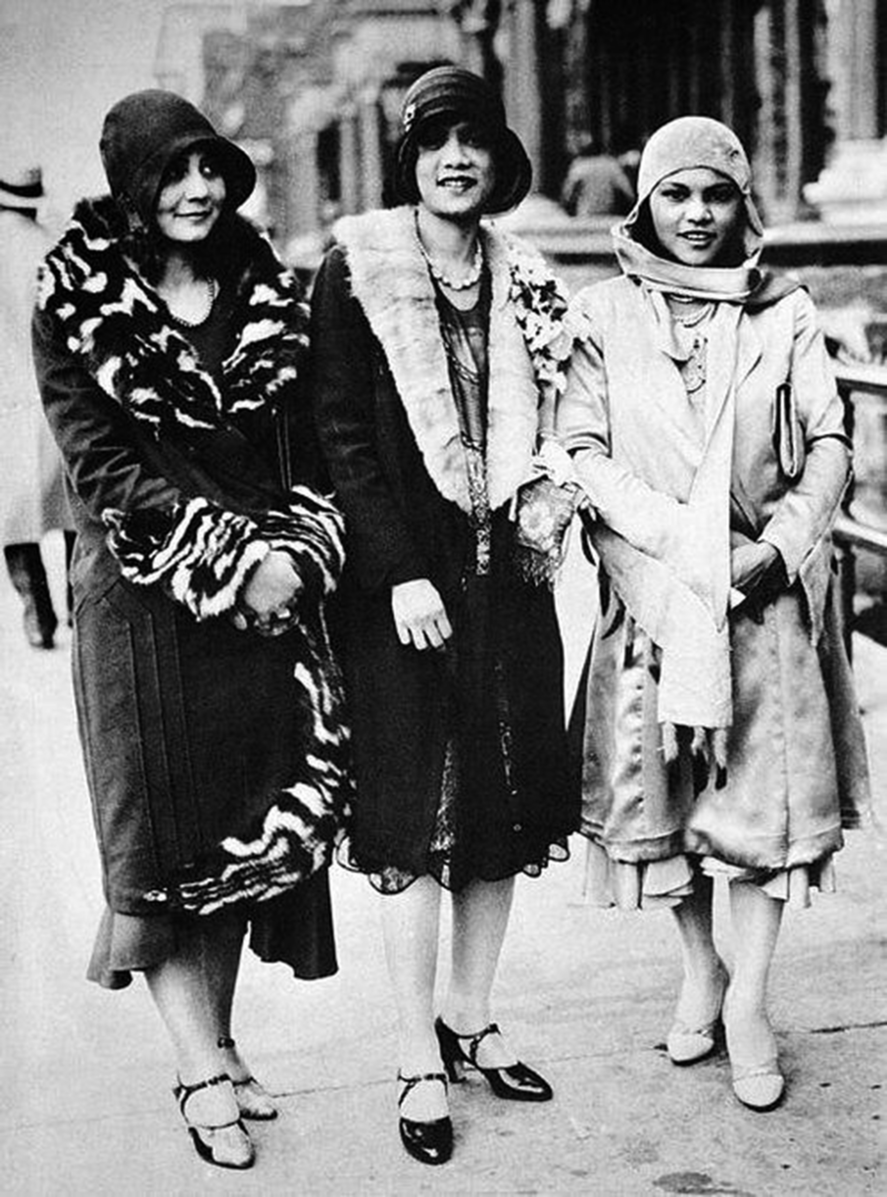

Largely due to differences in class (social rank) and aesthetic preferences, many leaders in the Harlem Renaissance believed that blues music was not appropriate for the aesthetic of Black art and culture they were trying to develop.

They felt the blues dwelled too much on the suffering of the past, and argued its deep-rooted connections with the rural South and lack of necessity of formal training did not reflect their perception of Black arts and the culture of the “New Negro.”

Three members of the Northeasterners, Inc., Edith Scott, Louise Swain, and Helene Corbin on Seventh Avenue in Harlem, unknown photographer, {{PD-US-expired}}. The New York Public Library.

James Weldon Johnson

For example, writer and activist James Weldon Johnson declared:

A people may become great through many means, but there is only one measure by which its greatness is recognized and acknowledged. . . the amount and standard of the literature and art they have produced. The world does not know that a people is great until that people produces great literature and art. No people that has produced great literature and art has ever been looked upon by the world as distinctly inferior.

James Weldon Johnson, by Doris Ulmann. National Portrait Gallery.

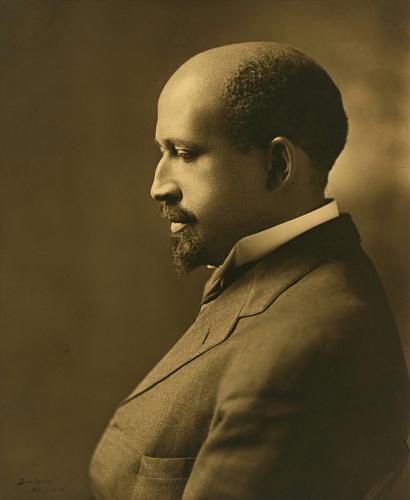

W.E.B. DuBois

Scholar and activist W.E.B. DuBois later argued:

W.E.B. DuBois, by Addison N. Scurlock. National Portrait Gallery.

If you . . . earnestly want to do something for Negro music, go to your record dealer and ask for the better class of records by colored artists. If there is a demand, he will keep them.

What does this quote suggest W.E.B. DuBois thought about the blues?

Music of the Harlem Renaissance

In short, the blues wasn't widely accepted by many involved in the Harlem Renaissance. Instead, other Black musical genres were preferred (such as arranged spirituals for choir or solo performance, operas, musical theatre, compositions blending Western classical and Black music aesthetics, ragtime, and early jazz.)

Eubie Blake

Paul Robeson

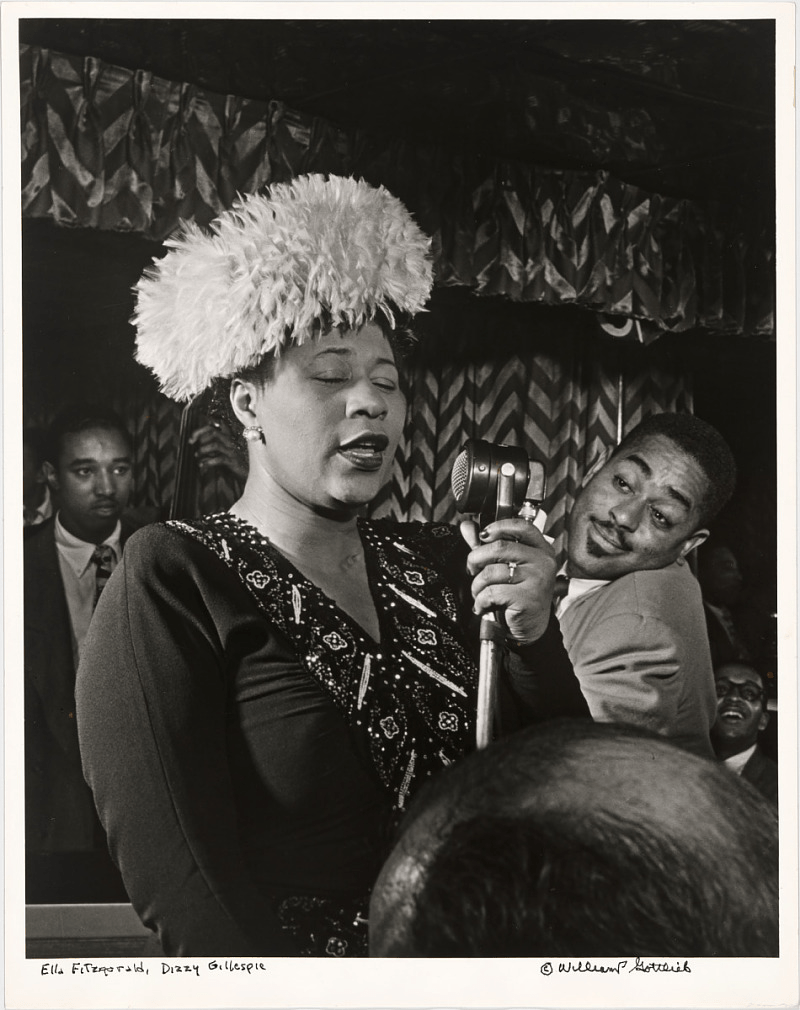

Ella Fitzgerald

Ella Fitzgerald (with Ray Brown, Dizzy Gillespie, and Milt Jackson), by William Paul Gottlieb. National Portrait Gallery.

Ella Fitzgerald, known as "The First Lady of Song," was an early vocal jazz star.

She was known for her vocal range, clear tone, and scat-singing abilities.

Ella's "big break" came at Harlem’s Apollo Theater in 1934.

"That Was My Heart," by Chick Webb and His Orchestra with Ella Fitzgerald

Paul Robeson

Paul Robeson During His tour in Moscow in August 1958, by Anatoliy Garanin. Associated Press.

He also played professional football and got a law degree from Columbia University!

"Swing Low, Sweet Chariot" by Paul Robeson

He is perhaps best-known for his rendition of the song "Ol' Man River" (from the musical Showboat).

Paul Robeson was one of the most famous African American actors and concert stage singers of the early 20th century.

Eubie Blake

Eubie Blake, by Duncan P. Schiedt. National Portrait Gallery.

Eubie Banks was an accomplished pianist and composer of ragtime music and musical theatre scores during the Harlem Renaissance.

Blake and lyricist Noble Sissle wrote a musical called Shuffle Along, which became a huge hit!

"Ma," by Eubie Blake

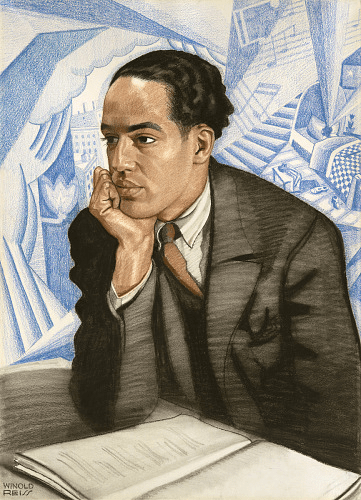

Langston Hughes

Unlike many of his peers, Harlem Renaissance poet and writer Langston Hughes deeply admired the blues.

Listen to Langston describe "the blues" in his own words:

Langston Hughes, by Winold Reiss. National Portrait Gallery.

"The Story of the Blues" by Langston Hughes

Langston Hughes and the "Blues Stanza"

In his poetry, Hughes sometimes used the blues lyrical form (AAB) as a means of narrating the stories of Black American workers in a familiar Southern dialect.

"Night and Morn" by Langston Hughes

Look at and listen to an example:

Sun's a settin', this is what I'm gonna sing.

Sun's a settin', this is what I'm gonna sing.

I feel the blues a-comin', wonder what the blues'll bring?

Sun's a risin', this is gonna be my song.

Sun's a risin', this is gonna be my song.

I could be blue – but I been blue all night long.

B

A

A

B

A

A

Attentive Listening Activity

Mamie Smith: "Crazy Blues"

Paul Robeson: "Swing Low, Sweet Chariot"

Listen for musical elements and expressive qualities.

Discussion

Which musical elements in "Crazy Blues" might have been viewed as “folk” (more rural) compared to what you heard in Paul Robeson's recording?

What do you think the rejection of these “rural elements” communicated to the many African Americans who supported and bought blues music?

Do you think these differences in aesthetic preferences created division between African Americans? Why and in what ways?

Bessie Smith: Empress of the Blues

Despite barriers, it is important to remember that there were several blues women who helped to bring blues music to a wider audience during this time.

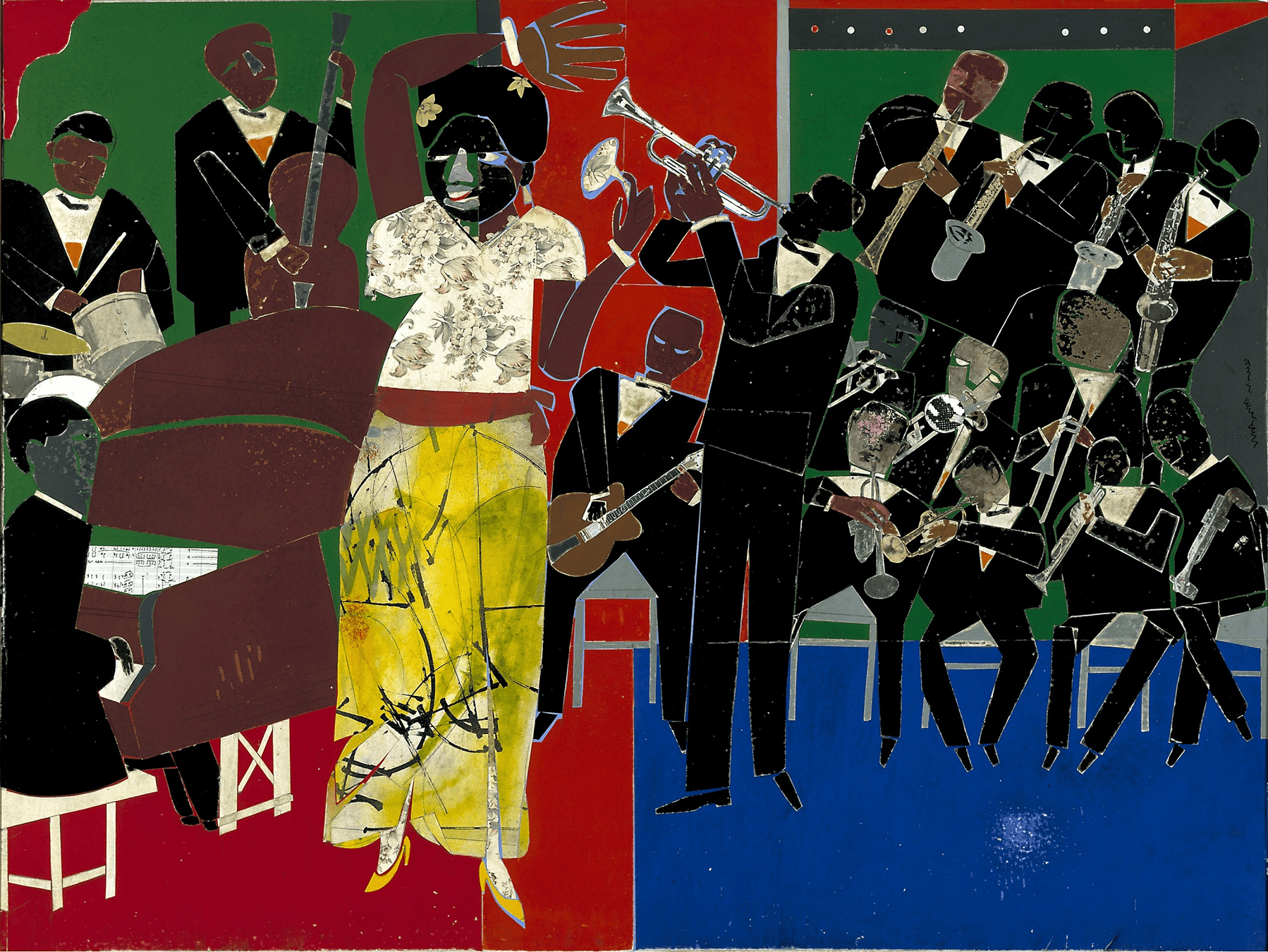

Empress of the Blues, by Romare Bearden. Smithsonian American Art Museum.

In fact, the cover image for the Women in the Blues pathways references Bessie Smith, a classic blues artist who thrived during the Harlem Renaissance, becoming the highest- paid Black entertainer of her time.

"St. Louis Blues" by Bessie Smith and Louis Armstrong

Learning Checkpoint

- What was the Harlem Renaissance?

- What are some music genres associated with the Harlem Renaissance?

- What are some similarities and differences between the blues and musical styles that were more readily accepted by the people involved in the Harlem Renaissance?

End of Path 2: Where will you go next?

Advertising the Blues

Path 3

30+ minutes

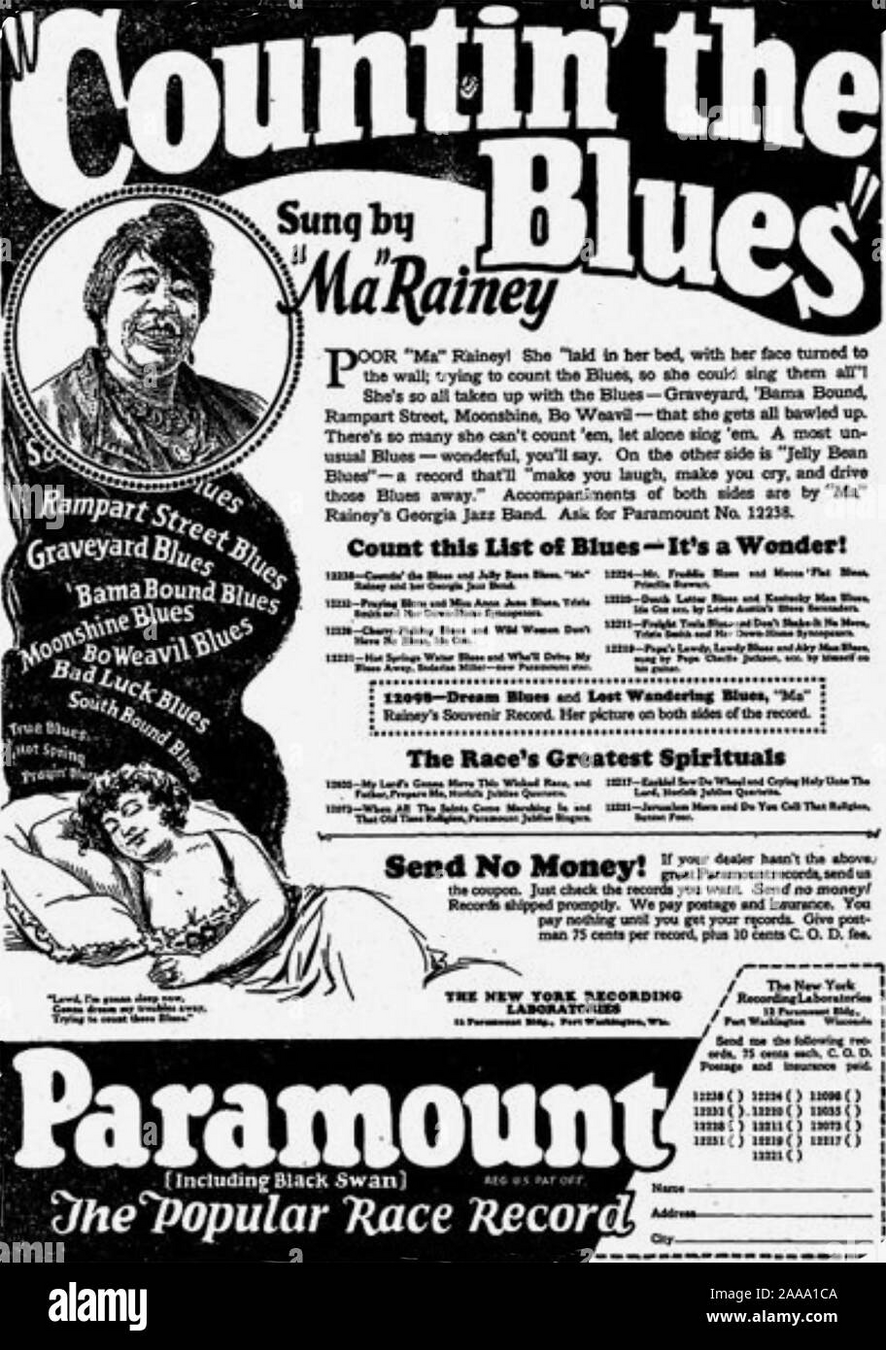

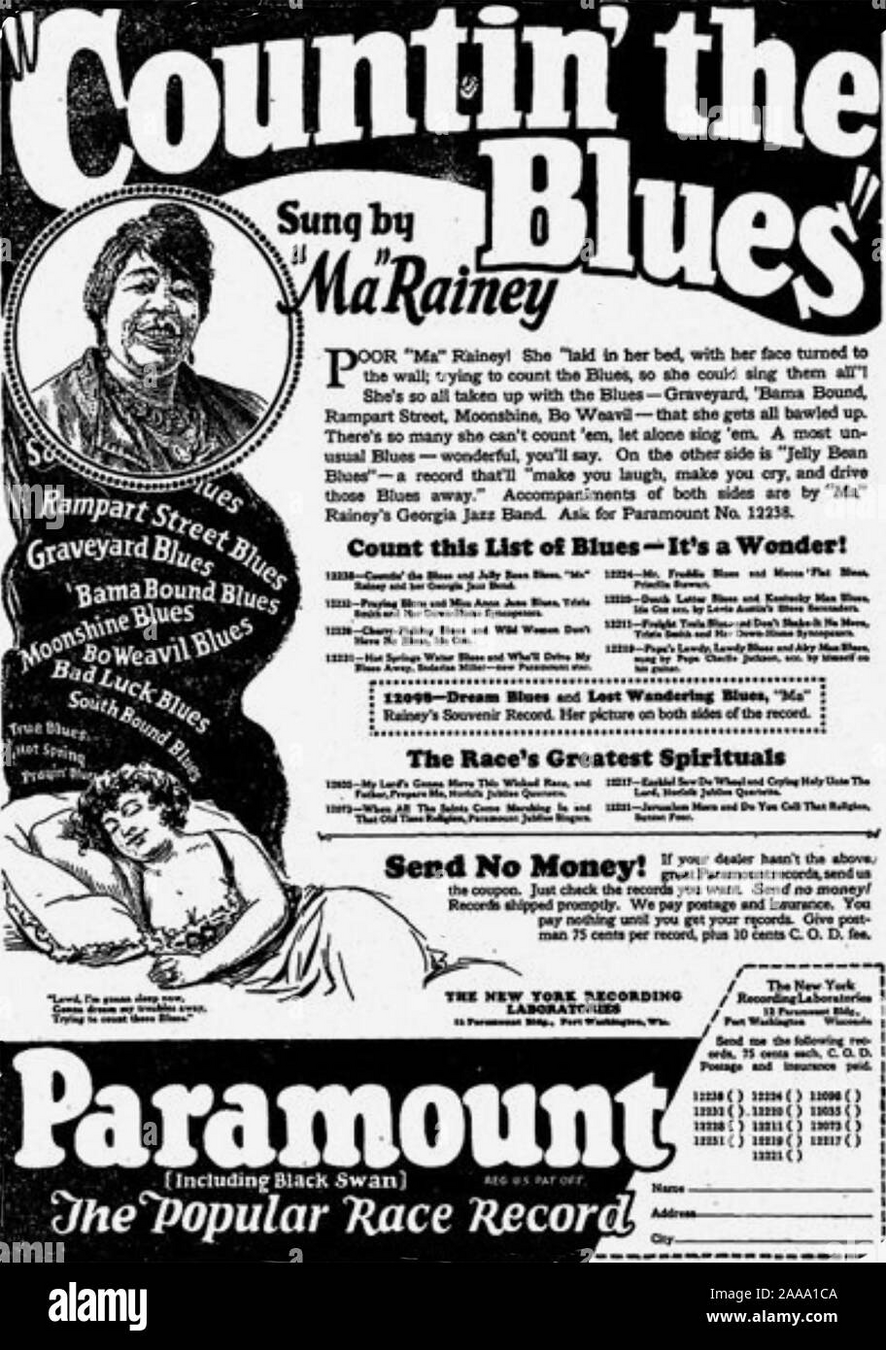

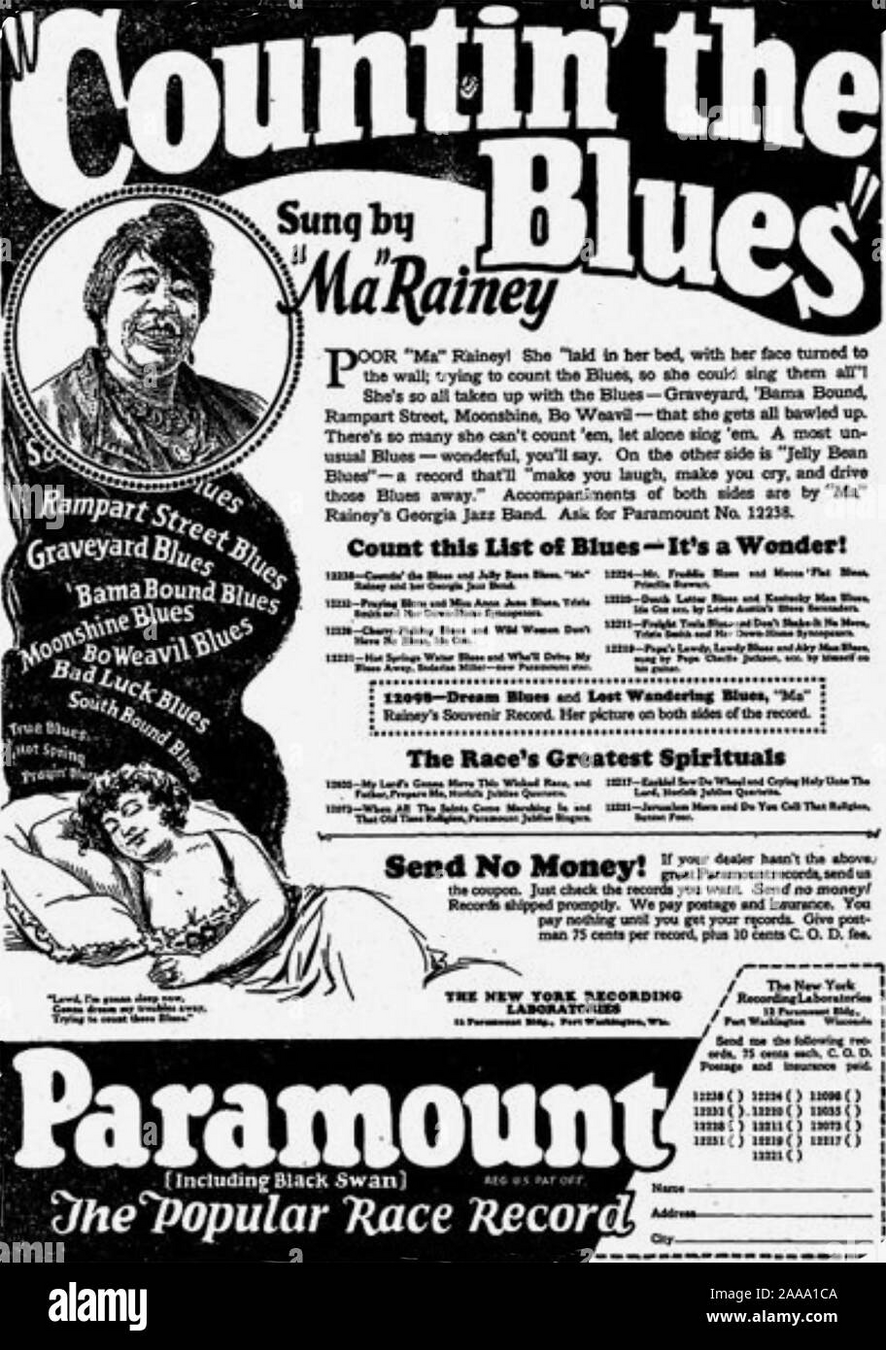

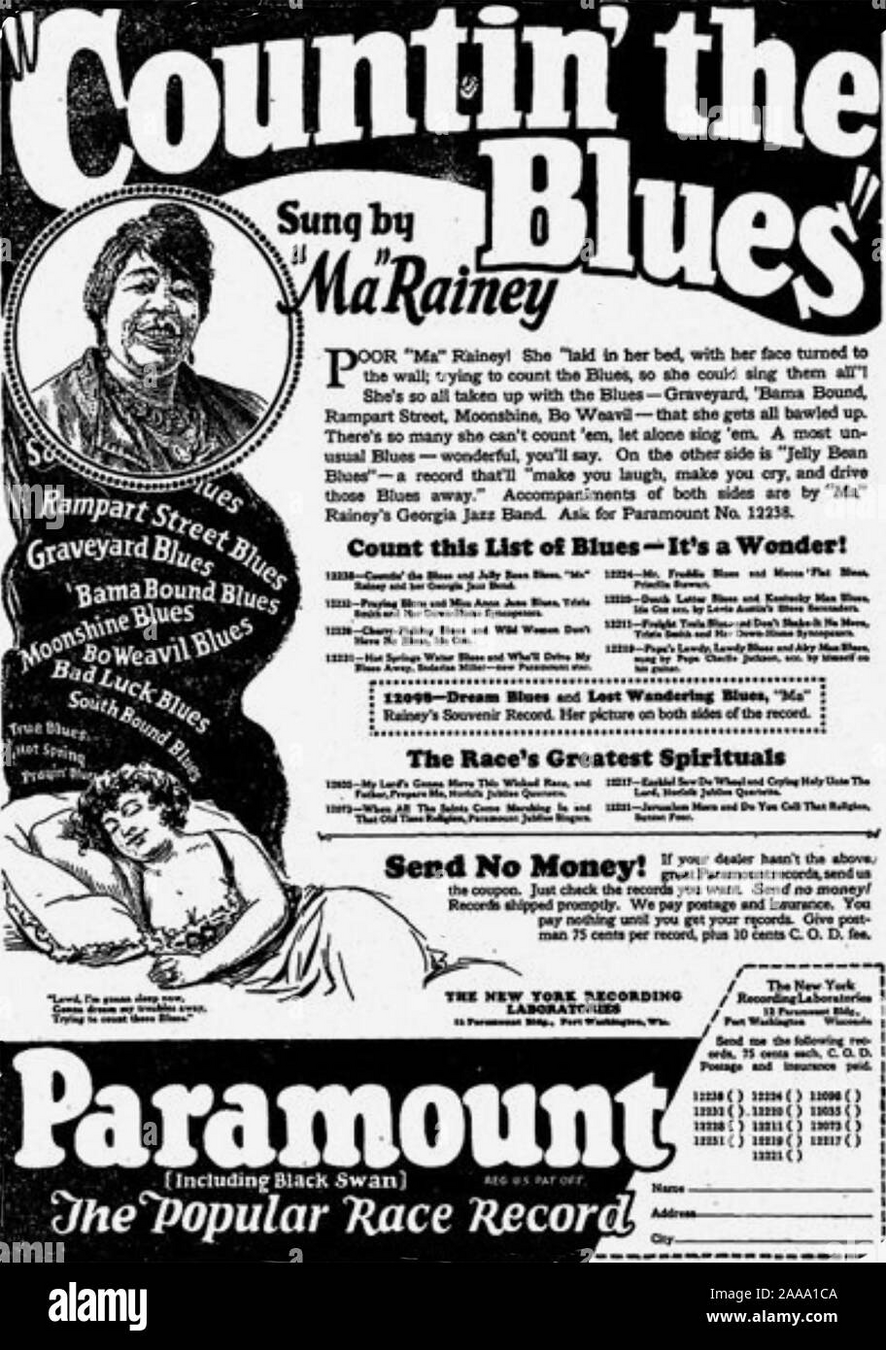

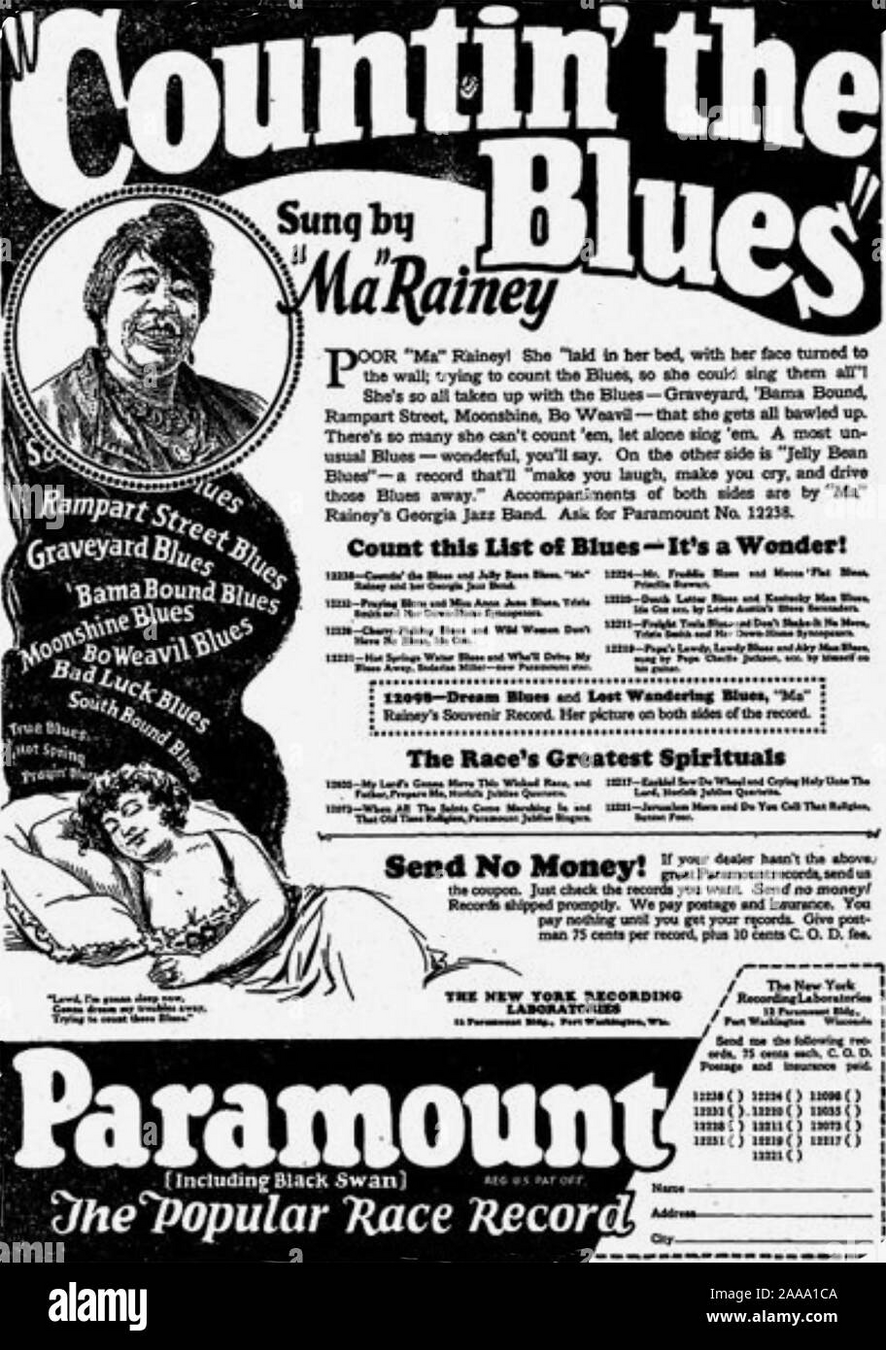

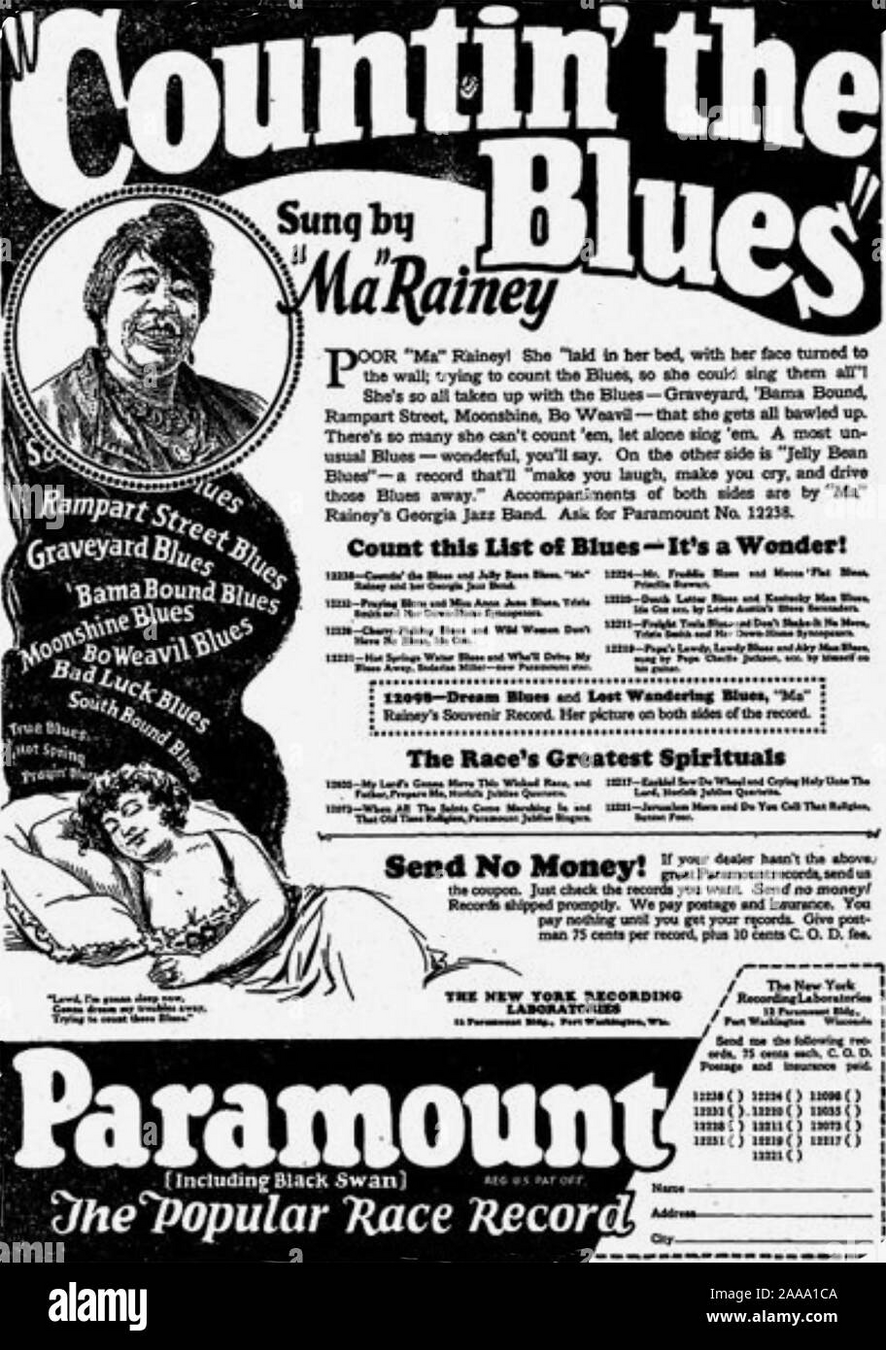

"Countin' the Blues" Sung by "Ma" Rainey, by Paramount, {{PD-US-expired}}. The Chicago Defender.

Advertising the Blues: Newspapers

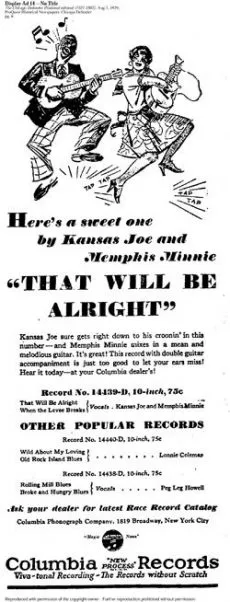

"That Will Be Alright" by Kansas Joe and Memphis Minnie, by Columbia, {{PD-US-expired}}. The Chicago Defender.

Advertising the Blues: Billboards

Advertising Billboards in Cincinnati, 1927. {{PD-US-expired}}. University of Cincinnati Archives.

Activity #1: Analyzing Early Blues Advertising

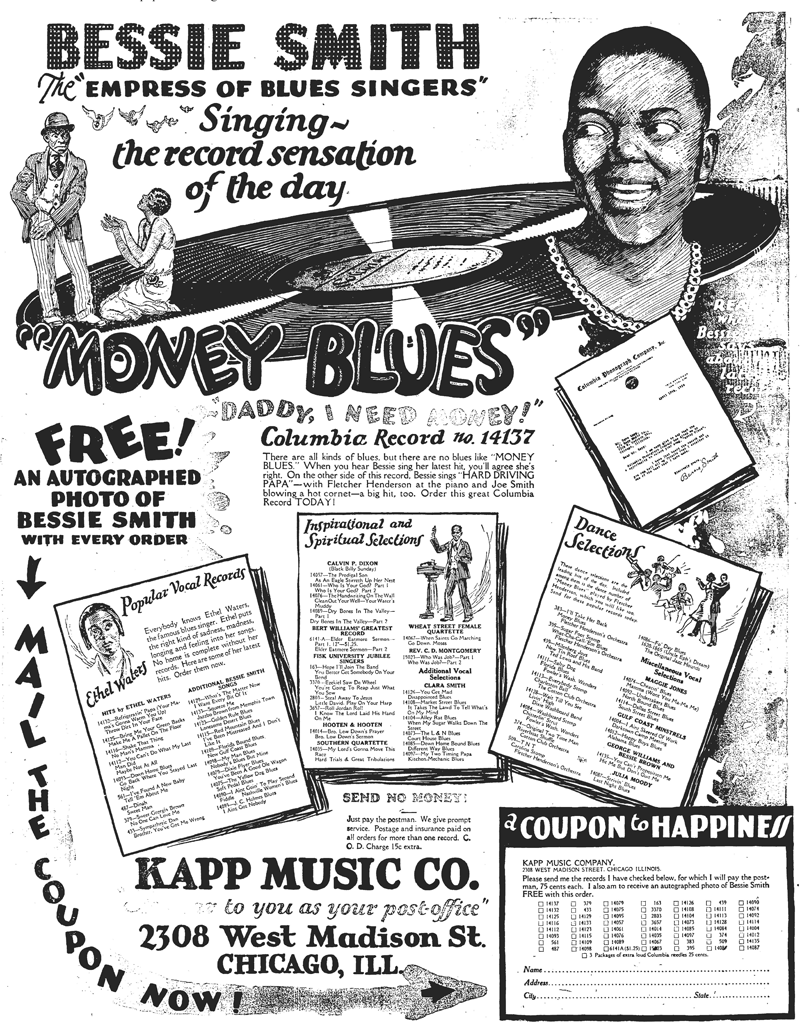

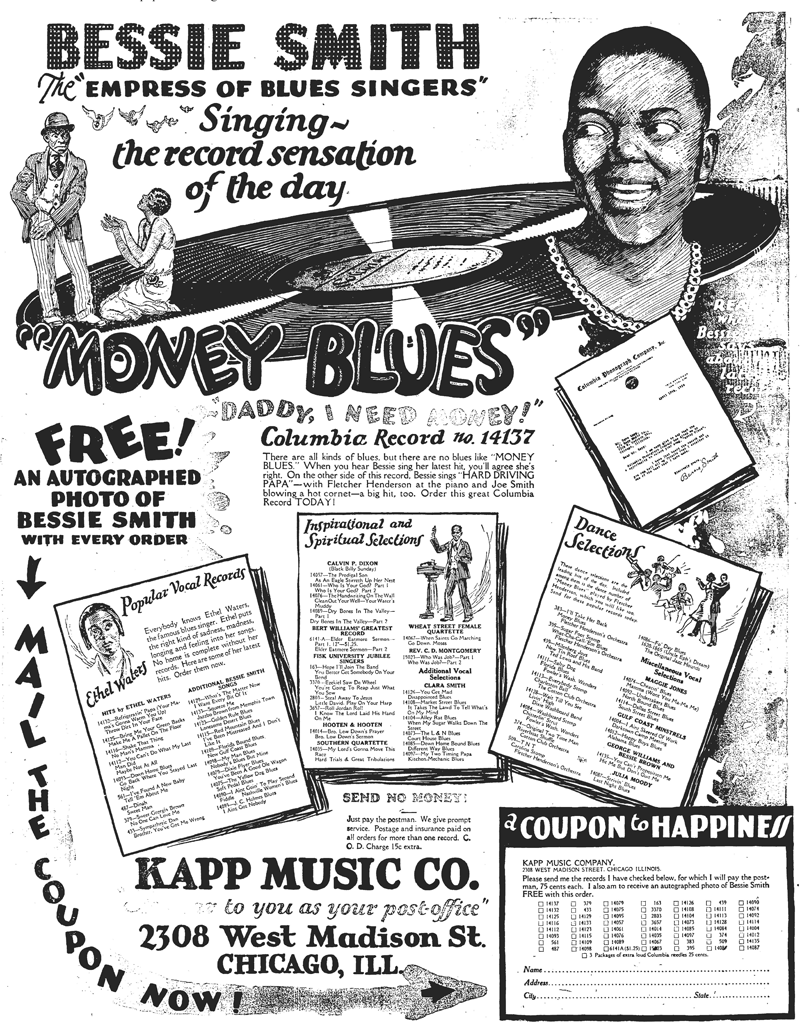

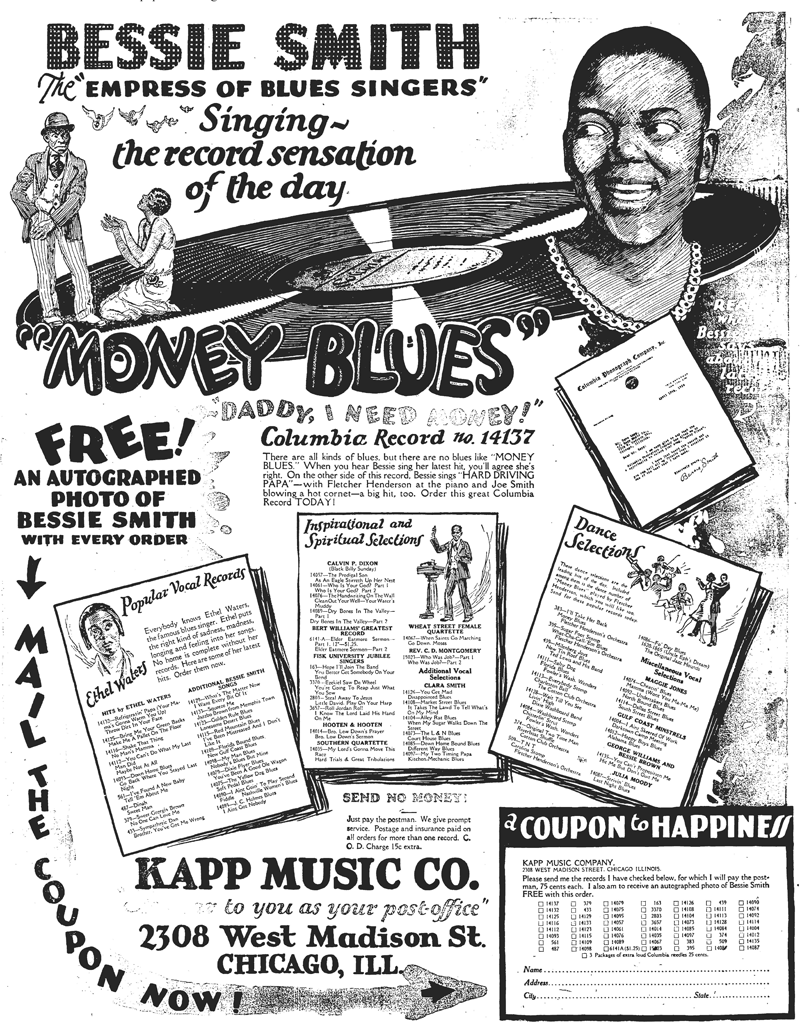

Let’s take a closer look at some advertisements for early blues recordings by three important blues women: Ma Rainey, Bessie Smith, and Helen Gross.

Remember, being "race records" (this label was usually included at the bottom of the flyer), these advertisements were intended for African American audiences.

For each ad, evaluate both the text and images. Consider these questions:

-

What do the images suggest?

-

What does the text suggest?

-

Do the ads reference any other musical genres that were popular during the time?

-

Is the poster flattering for the artist?

1. Ma Rainey: "Countin' the Blues"

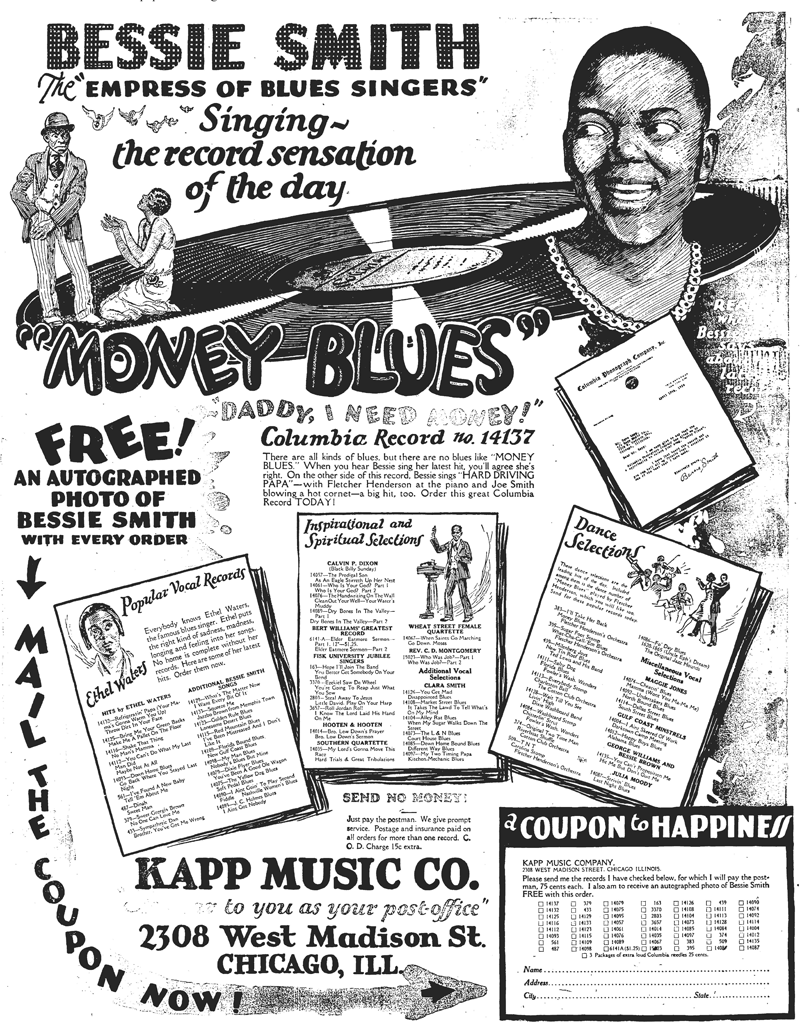

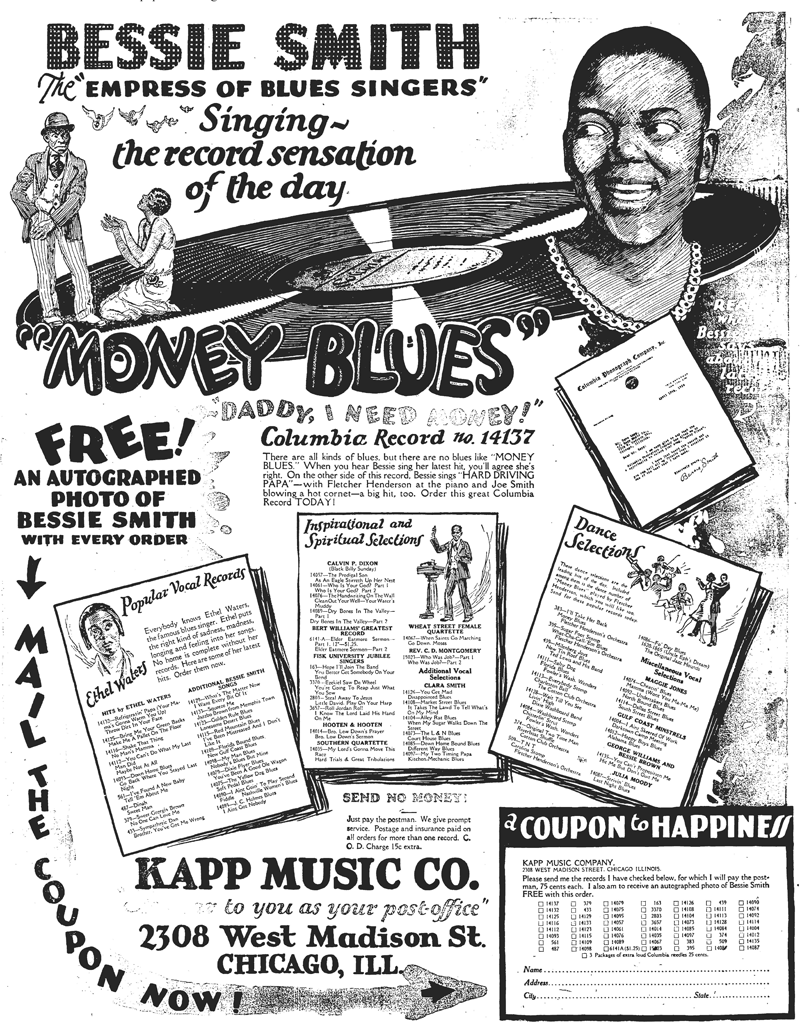

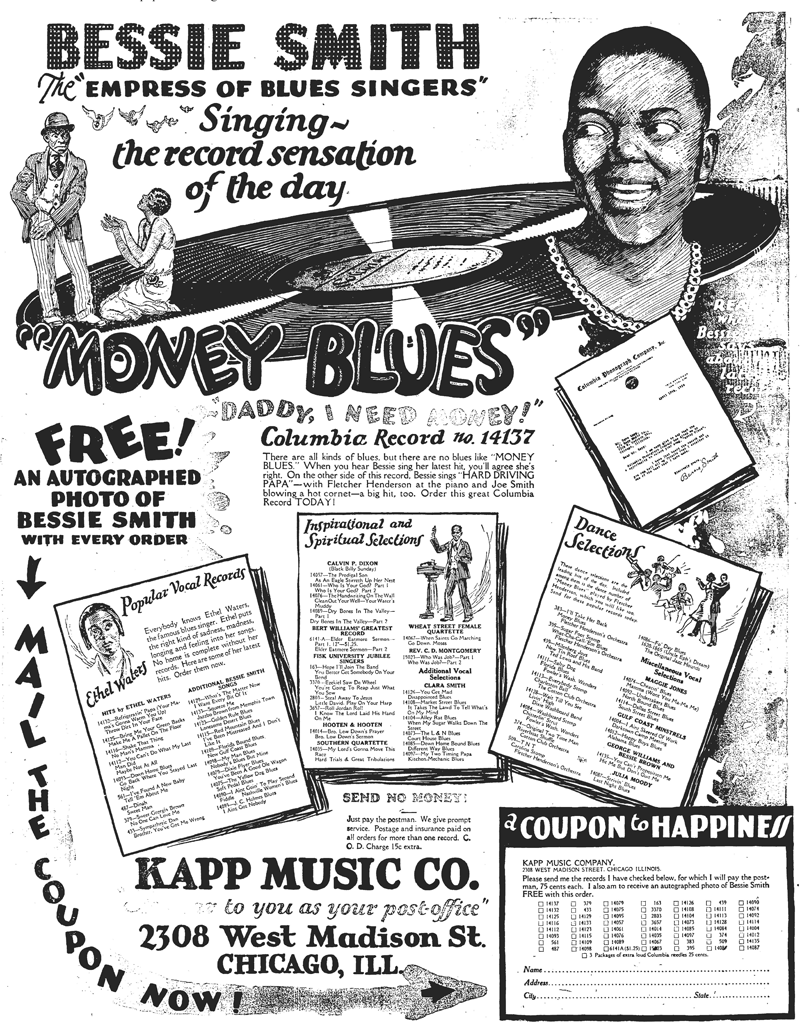

2. Bessie Smith: "Money Blues"

Bessie Smith, The Empress of Blues Singers, by Columbia Records, {{PD-US-expired}}. The Chicago Defender.

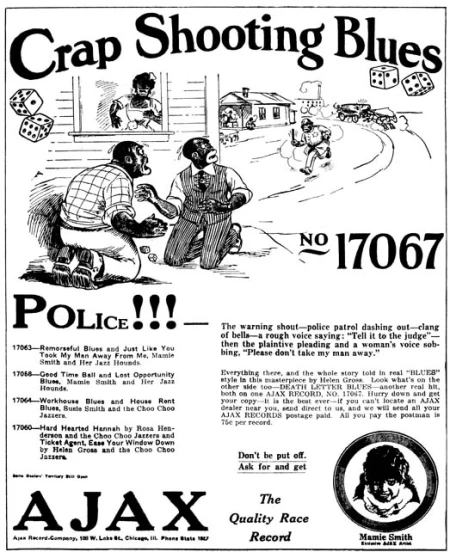

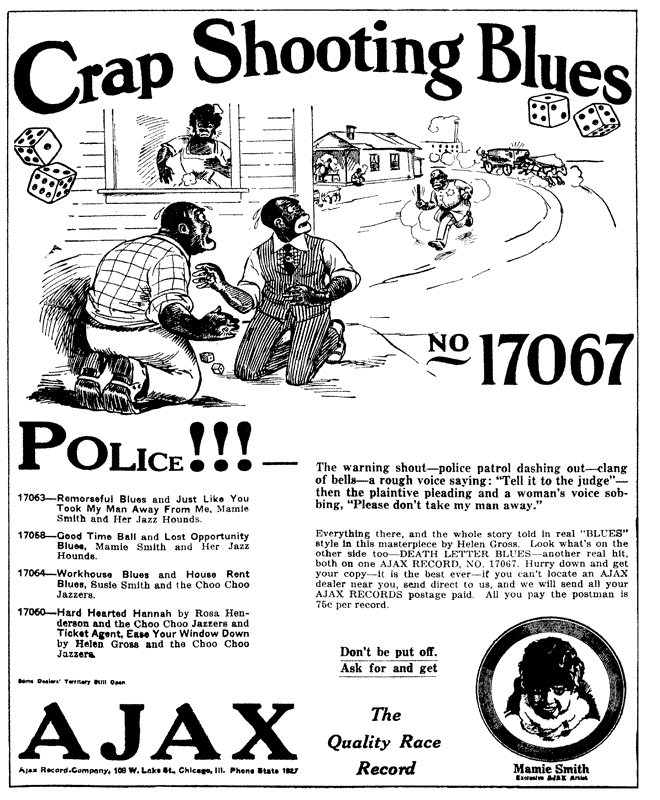

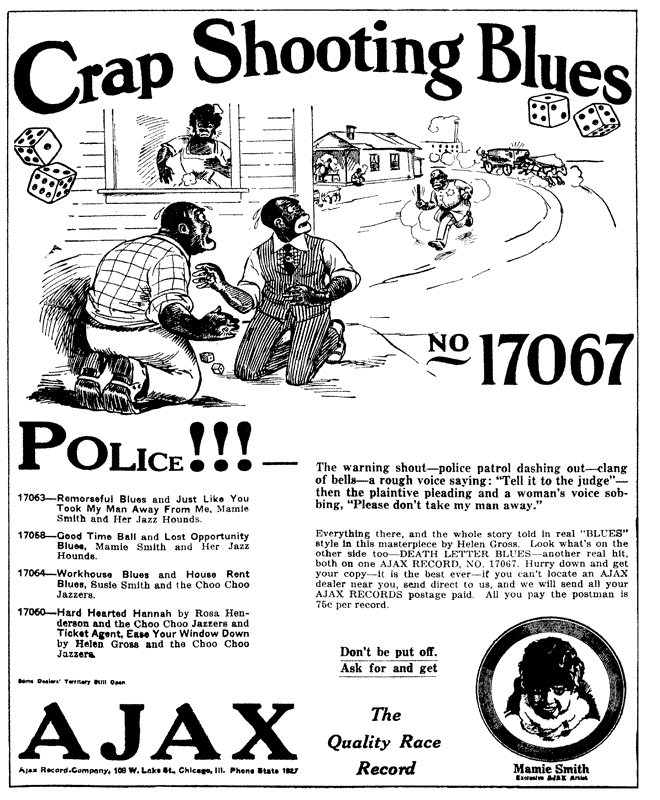

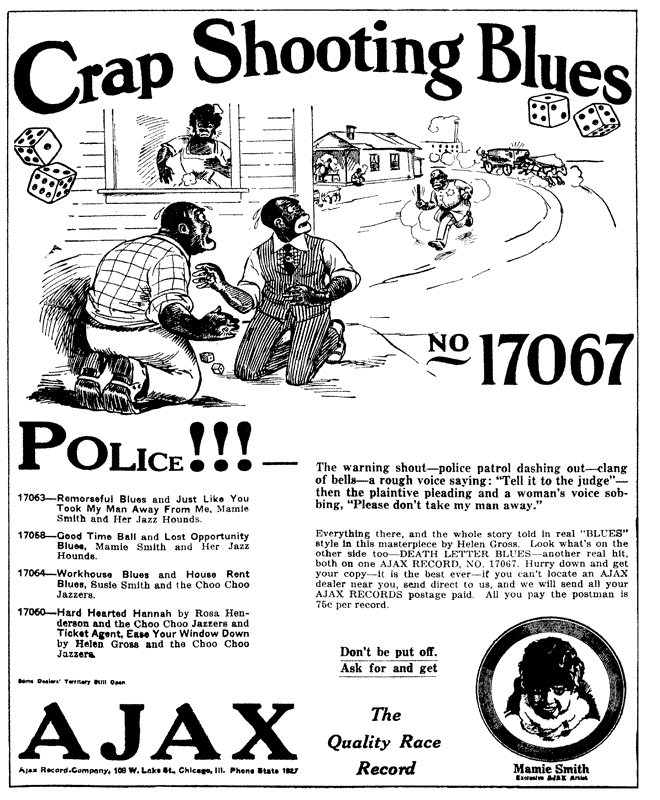

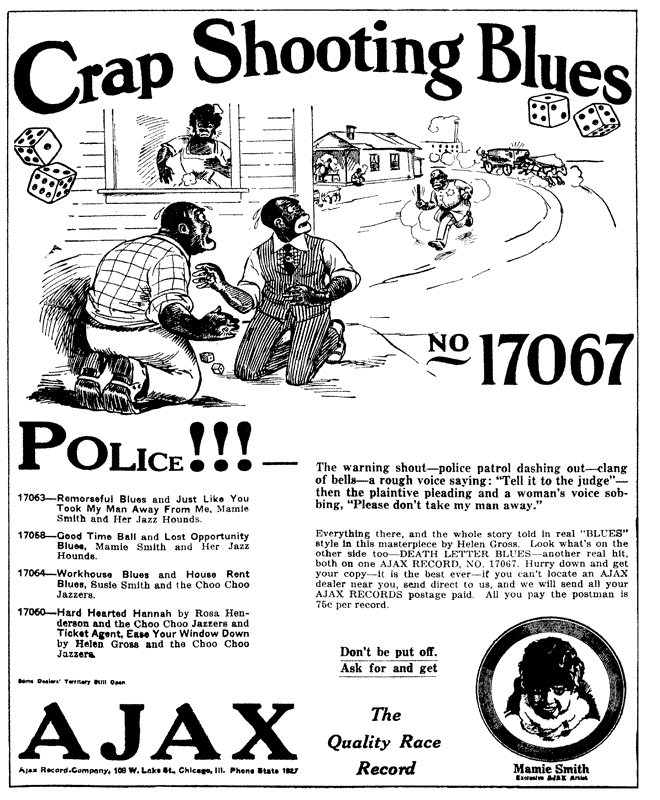

3. Helen Gross: "Crap Shooting Blues"

Crap Shooting Blues, by Ajax Record Company, {{PD-US-expired}}. The Chicago Defender.

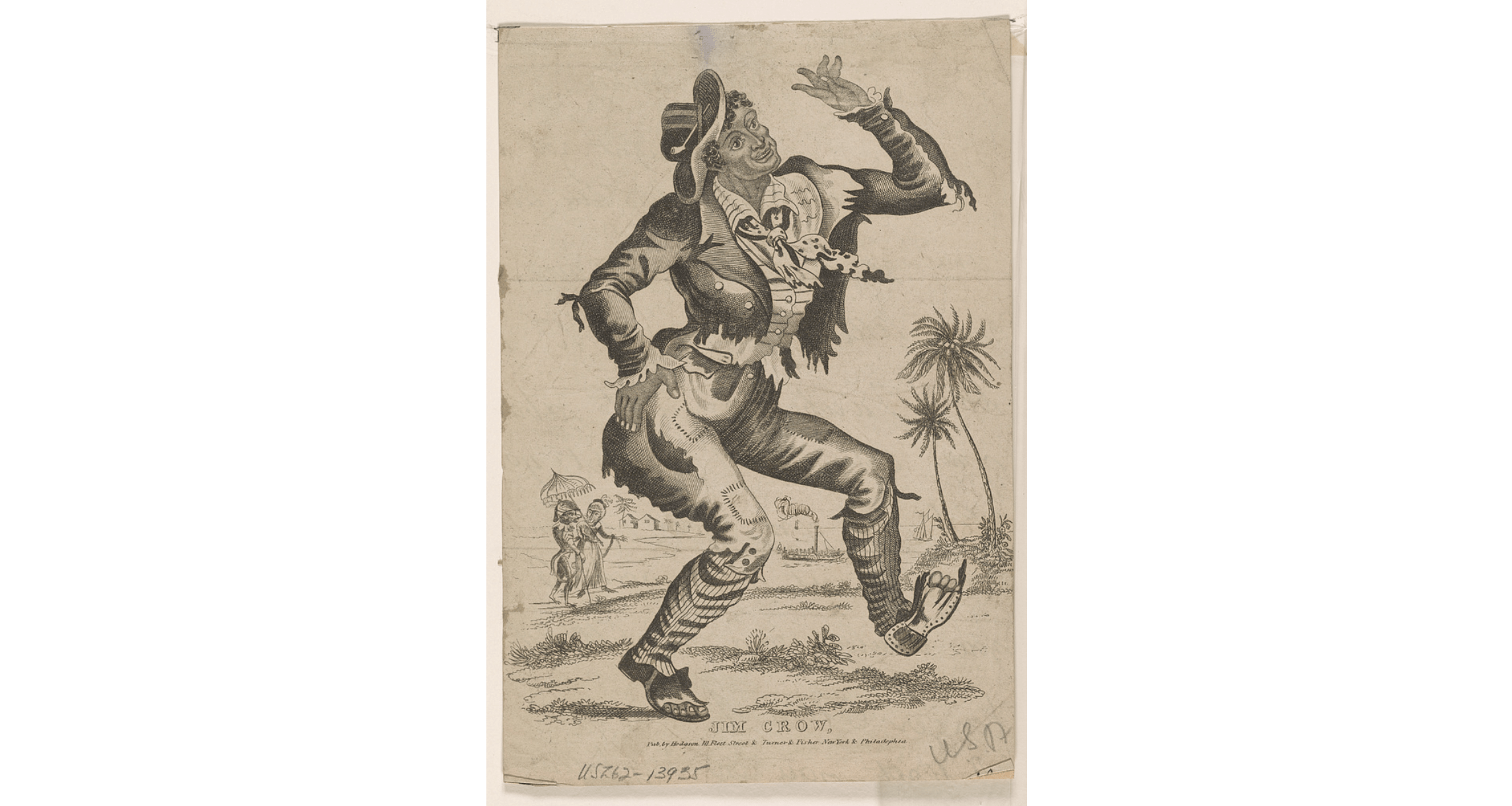

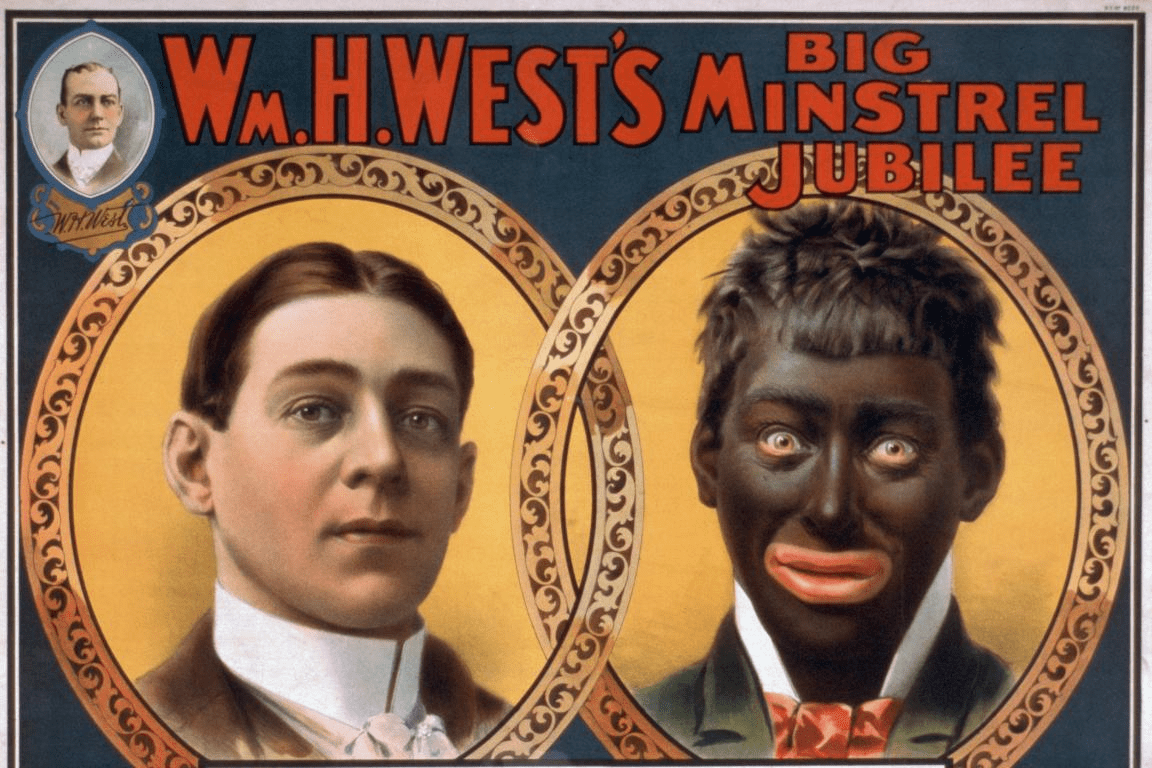

Minstrelsy

Left: Wm. H. West's Big Minstrel Jubilee, by Strobridge & Co. Lith. Right: Jim Crow, unknown artist. PD, The Library of Congress.

Music of Minstrelsy

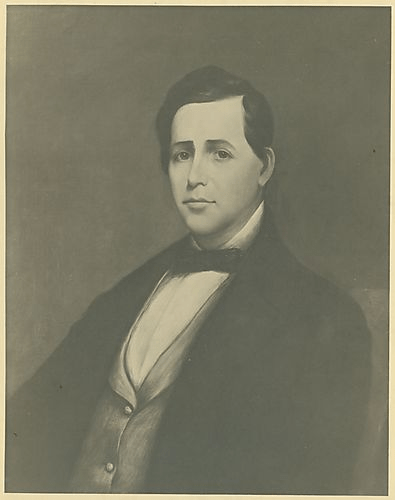

Did you know? Many popular camp songs and folk songs (some that you probably learned during childhood), were, in fact, written for minstrel shows.

Stephen Collins Foster, unknown artist, {{PD-US}}, via The University of Pittsburgh. Stephen Foster was a popular American composer who wrote many songs for minstrel shows.

Knowing this history, do you think these songs should still be taught and/or performed in classrooms and/or school concerts? Why or why not?

Some examples include: "Camptown Races," "Oh Susanna," "Jim Along Josie," "My Old Kentucky Home," and "Shoo Fly Don't Bother Me."

Discussion: Advertising the Blues

Ingenuity

Gender

Target Audience

Activity #2: Creating a Music Advertisement

Consider your favorite song and artist.

Design a flyer that advertises your selected song. Create your flyer as if this song is being newly released by the artist.

- Read more of the small print.

-

Get a sense of the genre and perhaps the lyrical content of the song, just from looking at the flyer.

-

Pique their interest so that they would want to listen to the recording, and potentially buy the record.

As you design your flyer, think about what might draw a stranger to do the following:

How would you advertise their hit song or album?

When you are finished, share your work with your class.

As you refine your work for presentation:

-

Ensure that your flyer is visually appealing,

-

Tells a compelling narrative about the artist and/or song, and

-

Appeals to the interest of others enough for them to want to listen to/buy the track.

Activity #2: Present or Display Your Work

Learning Checkpoint

- How were advertising flyers used to promote blues records (and other Black musics) in the early to mid 1900s?

- Even today, what can we learn from these early 20th century marketing campaigns?

End of Path 3 and Lesson Hub 8: Where will you go next?

Lesson 8 Media Credits

Audio courtesy of

Smithsonian Folkways Recordings

Video courtesy of

Smithsonian Institution Archives

Images courtesy of

Smithsonian American Art Museum

The University of Pittsburgh, ULS Digital Collections

Library of Congress

University of Cincinnati Archives

National Portrait Gallery

The New York Public Library

Jerry Butler

The University of Mississippi Libraries

Priceonomics

ANA Educational Foundation

Cornell University Library Digital Collections

National Museum of American History

© 2022 Smithsonian Institution. Personal, educational, and non-commercial uses allowed; commercial rights reserved. See Smithsonian terms of use for more information.

This Lesson was funded in part by the Grammy Museum Grant and the Smithsonian Youth Access Grants Program, with support from the Society for Ethnomusicology and the National Association for Music Education.

For full bibliography and media credits, see Lesson 8 landing page.