Fiesta Aquí, Fiesta Allá: Music of Puerto Rico

Lesson 6

Fiesta de Santiago Apostol de Loiza: Bomba and Community

What is Bomba?

Drmmers in the Batey, photo by Mariana Núñes Lozada. Smithsonian Folklife Magazine.

What is La Fiesta de Santiago Apostol de Loíza and why is it important?

Santiago Apóstol de Loíza: Bomba and Community

CREATIVE CONNECTIONS

HISTORY & CULTURE

MUSIC LISTENING

20+ MIN

30+ MIN

20+ MIN

What is the Fiesta Santiago Apóstol de Loíza?

Component 1

Bomba Dancer at Batey de los Ayala, Loiza, photo by Jaime O. Bofill Calero.

30+ minutes

- The Taino, the indigenous people of Puerto Rico called the island, Borinquen.

- Like many other places in the world, the Taino were forced into labor by European colonizers in the early 16th century.

- The rising demand for free agricultural labor resulted in the enslavement of West Africans.

- Enslaved labor produced wealth for the Spanish crown and for Spaniards in Puerto Rico.

- Slavery was abolished in 1873, but Spain continued to exert economic and political control in the island.

Historical Context: The Colonization of Borinquen

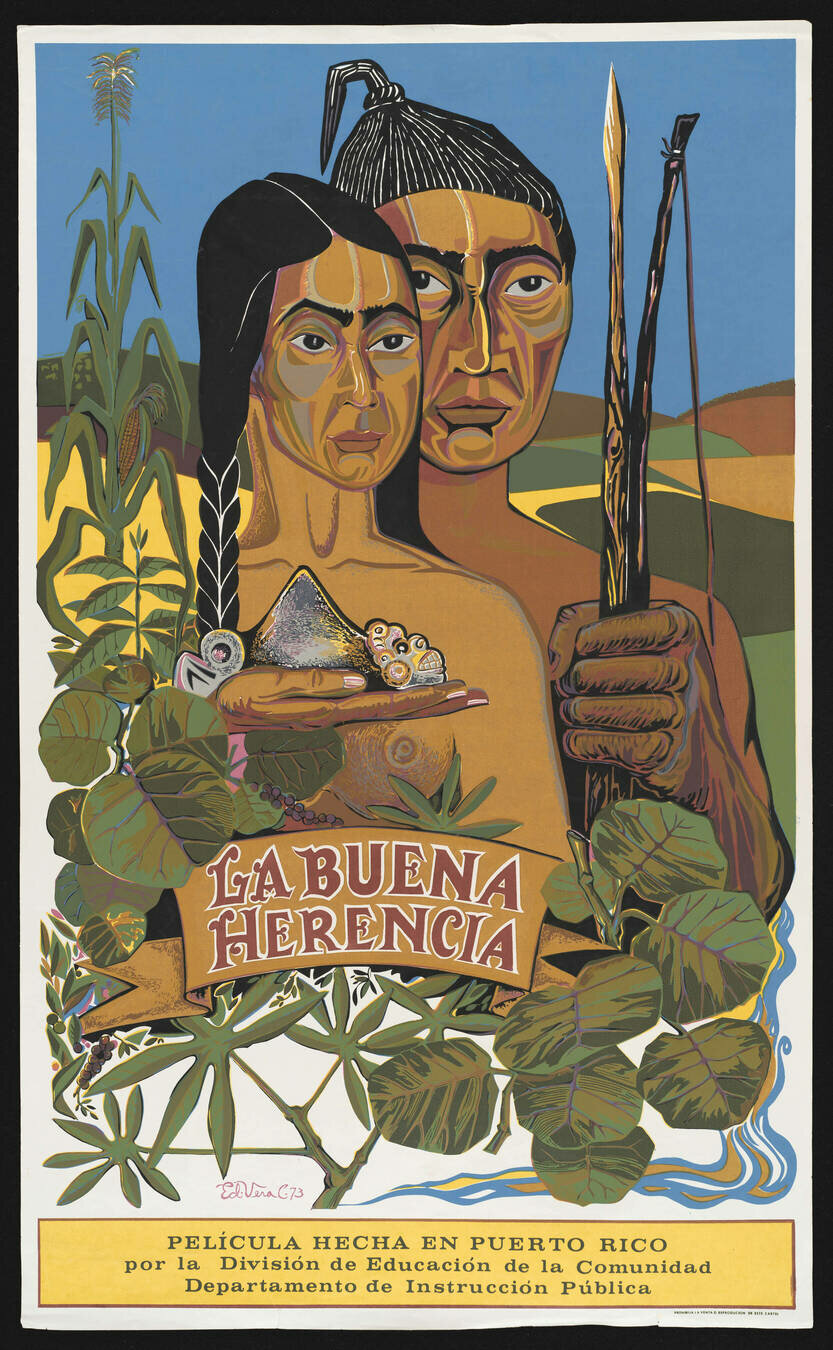

La Buena Herencia: Taino Portrayed as "Noble People", by Eduardo Vera Cortés. Museo de Historia, University of Puerto Rico.

Historical Context: Puerto Rican Identity

Towards the end of the 19th century, a distinct "Puerto Rican" identity began to emerge, which incorporated cultural elements of Indigenous, African, and European peoples.

While there are many shared aspects of Puerto Rican identity, there are also as many challenges that arise due to racial and class barriers, still connected to earlier colonial times.

Barriles and Cua, photo by Mariana Núñez Lozada. Smithsonian Folklife Magazine.

Historical Context: Puerto Rican Sovereignty and National Identity

- Puerto Rico became independent from Spain at the end of the Spanish-American War in 1898.

- However, the US refused to leave after the war and annexed Puerto Rico.

- Officially, Puerto Rico is an unincorporated territory of the United States.

Flag of Puerto Rico, by Cerejota and Sarang. Flag of the United States, by Dbenbenn, Technion, and Steinsplitter. CC-PD-Mark, via Wikimedia Commons.

Cultural Dialogues: Bomba

Bomba music provides a clear example of this cultural dialogue.

As you have learned throughout this pathway, Puerto Rico identity is uniquely tied to its great diversity.

Each group that has been a part of Puerto Rico's history has contributed to its unique cultural activities.

"Bomba," by Ensemble from Loíza Aldea (P.R.)

Bomba: African Influences

What is "African" about this music?

Bomba Drum, unknown maker. National Museum of American History.

Bomba music (and dance) draws its strongest influences from West African countries (e.g., Ghana, Congo, Angola).

Listen to "Bomba" again.

Loíza and Bomba

Bomba is one of the musical centerpieces of Loíza, an Afro-Puerto Rican town established by cimarrones (formerly enslaved people).

- People from Loíza are called Loiceños.

- Although the area is largely populated by African descendants and popular music genres reflect West African roots, most Loiceños do not define themselves by race. More than anything, they identify as Puerto Rican.

Puerto Rico (Small Map), by U.S. Central Intelligence Agency. University of Texas Libraries. Loíza is circled in red.

Loíza and Blackness

A problematic notion rooted in the colonial period links "Blackness" to notions of "primitiveness".

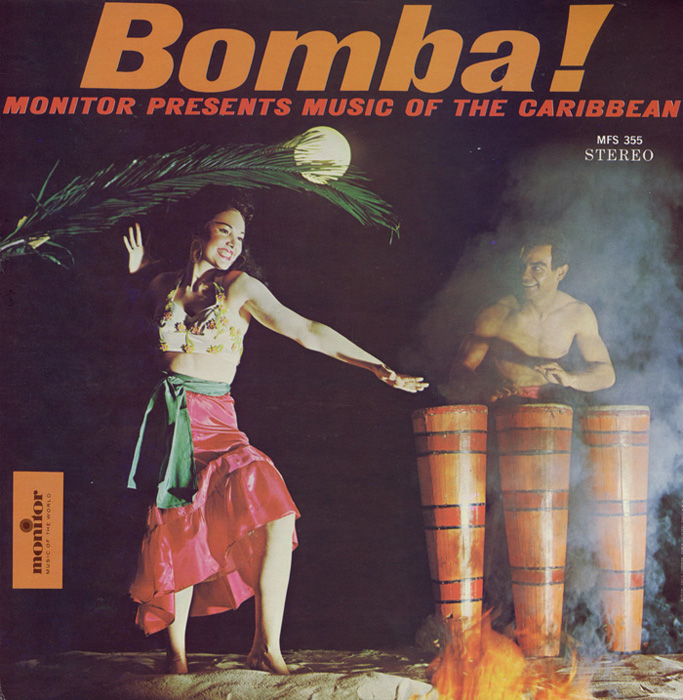

Bomba!, unknown artist. Monitor Records.

Though false, this characterization has been harmful in places like Loíza: It promotes racial divisions and marginalizes people and their music traditions.

In reality, Loíza provides a great representation of African-influenced culture—as seen in practices and performances of music like plena and bomba.

Bomba: Secret Codes and Haitian Connections

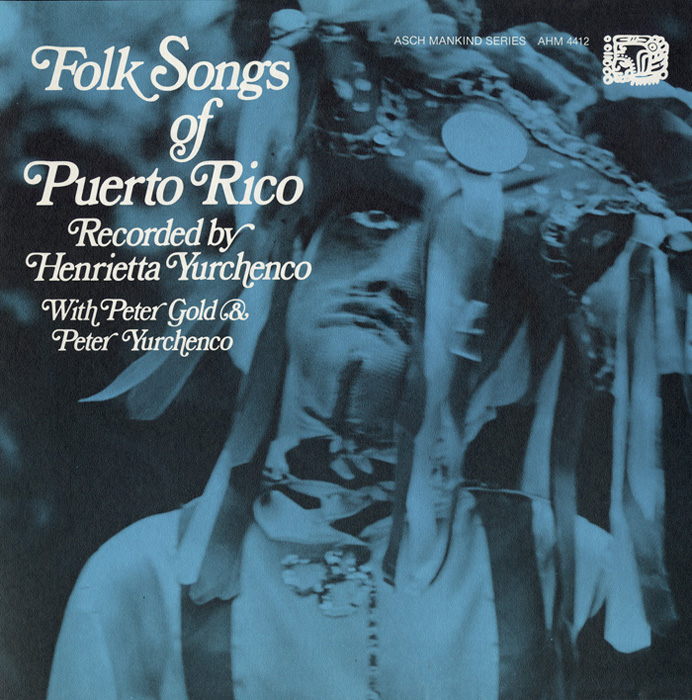

Folk Songs of Puerto Rico Cover, by Ronald Clyne. Folkways Records.

- These gatherings were often a medium to plan liberation: The loud music served as a distraction as people used chants and rhythms to plan escape routes without the knowledge of the slave owner.

In addition to Loíza, bomba developed in other Puerto Rican coastal towns (such as Ponce, San Juan, and Mayagüez), among Afro-Puerto Ricans and Black Haitian immigrants.

- Enslaved people would gather socially to play music at events called bembes.

"Ven Aca Ven Aca /Meliton Tombe," by two drummers and singers at the fiesta of Santiago in Loiza Aldea (1967).

Loíza: Irish and Catholic Connections

Another enduring aspect of cultural life in Loíza specifically and Puerto Rico in general is Catholic practice.

- The official patron of Loíza is San Patricio (Saint Patrick).

- During the colonial period, Irish immigrants owned many plantations on the island.

- Loiza's downtown features a beautiful Catholic church: Church San Patricio y Espiritu Santo (En. Saint Patrick and Holy Spirit).

Church of San Patricio Loiza, by Jaime O. Bofill Calero.

Santiago Apostol: Matamoros, the Moorslayer

Although San Patricio (St. Patrick) is the official patron saint of Loíza, the most obvious and pervasive Catholic symbol in the region is Santiago Apostol (i.e., St. James).

Colonizers of Puerto Rico looked up to St. James, nicknamed Matamoros (En., Moor killer) for his mythical participation in the Battle of Clavijo, when Spanish Christians defeated Muslim Moors.

Santiago Apostol, unknown artist. National Museum of American History.

Santiago Apóstol: Matamoros, the Moorslayer

Image of Santiago de los Niños, photo by Jaime O. Bofill Calero.

However, in Loíza, among Afro Puerto Ricans, Santiago symbolizes freedom and protection.

It might seem strange that the image of a "moor killer" is celebrated in a town heavily populated by people with African heritage.

Fiesta Santiago Apóstol de Loíza!

The Fiesta Santiago Apóstol de Loíza is celebrated for 10 days, from the 24th of July to the 2nd of August!

The festival is deeply connected to the Roman Catholic Church in Puerto Rico:

- Masses, prayers (called novenas), weddings, and baptisms are frequent.

- Community gatherings and fundraising events contribute to the festival atmosphere.

- Bomba performances are common at town squares or on stages.

Girl Dancing Bomba at Fiesta de Santiago Apostol, photo by Lowell Fiet. Digital Library of the Caribbean.

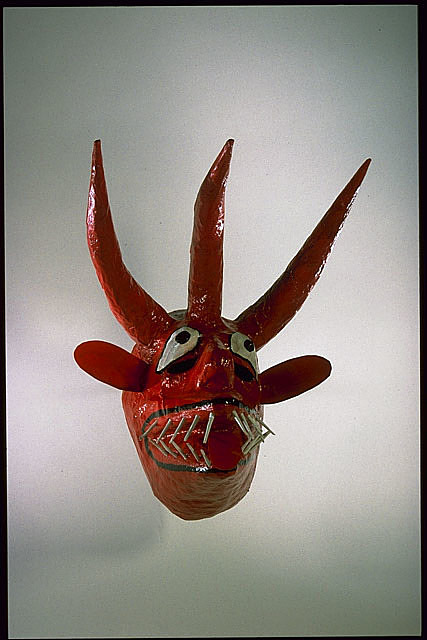

Vejigantes and Caballeros

Others dress as caballeros (gentlemen/cowboys), representing the protectors of Santiago.

Mosaic of Vejigante and Caballero in Loíza Town Square, by Daniel Lind. Photo by Jaime O. Bofill Calero.

Vejigantes and caballeros are two of the most important symbols of the festival.

People dress as vejigantes (pagan demon characters based in folklore), donning masks featuring three horns, complimented by brightly-colored costumes.

Legend of the Fiesta

The next morning, the stature miraculously appeared at the base of the tree where the old lady had originally found it.

A legend of the festival's origin claims an old woman found a Santiaguito (a nine-inch statuette of baby Santiago) by a tree and took it to a priest, who locked it in the church.

Devotees With Statue of Santiaguito, photo by Jaime O. Bofill Calero.

The priest called this a miracle and said each year there should be a procession from this tree to the church, and around the town.

A Processing Fiesta

Musicians play on movable floats or carretón alegre (happy cart), designed with festive colors and creative ornaments.

Carretón Alegre During Procession in Loiza, photo by Lowell Fiet. Digital Library of the Caribbean.

During Fiesta Santiago Apóstol de Loíza, statues of Santiago are carried across neighborhoods for three days.

- In Loíza, the statues are taken in a symbolic procession from a local house to church.

The Three Statues

Three statues of St. James are cared for in three separate households in Loíza.

- The people who care for the statues are called mantenedores (maintainers).

- The three statues have different purposes: Santiago of Men, Santiago of Women, and Santiaguito (Santiago of the Children).

- When set inside the homes, they are not on altars: People are still able to come inside the home to talk to the statue and to ask for promises.

- Fiesta Santiago Apóstol de Loíza is the only time of the year when the three statues are together.

Optional: "Music as Order and Chaos"

Music as Order and Chaos: Fiesta de Santiago Apóstol de Loiza, by Jaime O. Bofill Calero.

Learning Checkpoint

- How did bomba music develop in Puerto Rico?

- What are the origins of the Fiesta Santiago Apostol de Loíza, and what is its social significance?

End of Component 1: Where will you go next?

What is Bomba Music?

Component 2

30+ minutes

Bomba at Batey de los Ayala, Loiza, photo by Jaime O. Bofill Calero.

Bomba!

Watch this bomba performance for

a Fiesta Santiago Apóstol

in Loíza's Matauri neighborhood.

What do you notice about the instrumentation, dancing, singing, and rhythms?

Toque de Bomba en el Barrio de Maturi, uploaded by Con Espiritu Utópico. Start video at 09:10.

Fiesta Santiago Apóstol de Loíza!

The Fiesta Santiago Apóstol de Loíza is celebrated for 10 days, from the 24th of July to the 2nd of August!

- It is an important community gathering in Loíza, a coastal town in Puerto Rico.

- It is related to the Roman Catholic Church: Masses, prayers (called novenas), weddings, and baptisms are frequent.

- Bomba performances are common at town squares or on stages.

- People often dress up in costumes - it is a "Carnival-like" atmosphere.

Vejigante and Caballero in Loíza, by Jaime O. Bofill Calero.

Bombastic Bomba

The term bomba translates to "bomb", but it can also be interpreted as an expression of its sound—a big boom.

Girl dancing bomba at Fiesta de Santiago Apostol, photo by Lowell Fiet. Digital Library of the Caribbean.

Historically, the term bomba referred to a type of drum (bamboula).

Today it is used to refer to all aspects the music: the genre itself; the name of the full group of performers; the dance (e.g., "baile de bomba"; drums "tambores de bomba").

Bombastic Bomba

Bomba is performed by drummers, dancers, and singers.

Performers and audience members gather in a circle, creating a space in the middle for dancing called the soberao (also called the batey).

- This set-up enables unobstructed views between drummers and dancers.

Bombazo Batey de los Ayala Loiza, by Jaime O. Bofill Calero.

Bomba and Gender

Unlike other male-dominated drumming traditions in the region, bomba is practiced by both male and female participants:

- It can be danced in pairs or individually.

- Solo dancers are usually woman.

- While dancing, women usually move their upper body (arms, shoulders, hands), while men use their lower body more (legs and feet).

Juan Carlos Dances in the Batey, photo by Mariana Núñez Lozada. Smithsonian Folklife Magazine.

El Piquete

Piquete is a term that describes the musical dialogue between dancers and drummers.

- At first, the dancer enters the soberao circle, greeting the drummers by performing a paseo (stroll).

- The dancer then moves to the rhythm and the drummer responds to the dancer's moves, altering and developing its rhythmic improvisation.

A Bomba Piquete Scene, photo by Mariana Núñex Lozada. Smithsonian Folklife Magazine.

El Piquete in Action

Watch this video of Viento de Agua performing traditional bomba at the 2004 Smithsonian Folklife Festival.

Observe the piquete (interaction between the dancer and drummers).

Bomba Fashion

When participating in bomba, women sometimes:

- Wear a "blusa ya falda" (a two-piece folk dress)

- Wear a flowy skirt

- Wear an "amapola" in their hair (the Puerto Rican national flower)

- Wear a head wrap or headband

- Wear casual/street clothes—especially when performing at town squares and other informal gatherings

Los Pleneros de la 21, photo by Erika Rojas. Smithsonian Folkways Recordings.

Instruments: Barril de Bomba

Bomba rhythms are played on barriles de bomba or simply, barriles (bomba barrels). They are classified according to their function and size:

- Subidor/primo: lead, smaller, plays repique (improvises)

- Buleador/segundo: bigger and wider, performs an ostinato pattern to lay down the groove

Barril de Bomba, unknown maker. National Museum of American History.

Watch this short video to learn more about barriles de bomba

How is a Puerto Rican Bomba Drum Created?, narrated by Marvette Perez. Smithsonian Music.

Instruments: Cuá, Güiro, and Maracas

The cuá is a hollow log struck with a stick on the body.

The güiro is a ridged gourd scraped with a stick or fork.

Maracas are gourds filled with seeds. They are shaken.

These bomba instruments belong to the idiophone family and are of Taino origin:

Edwin Estrema Playing the Cuá, unknown photographer. New Jersey State Council on the Arts.

Puerto Rican Güiro, unknown maker. National Museum of American History.

Maracas, unknown maker. National Museum of American History.

Bomba Grooves

Bomba music has 16 distinct rhythms:

- They vary in meter (6/8, 2/3, and 3/4).

- Each rhythm is associated with a different region in Puerto Rico.

- Seis corrido is the bomba variant performed in Loíza.

A Seis Corrido Bomba Class in Majestad Negra, Loiza, uploaded by Liv Nieves.

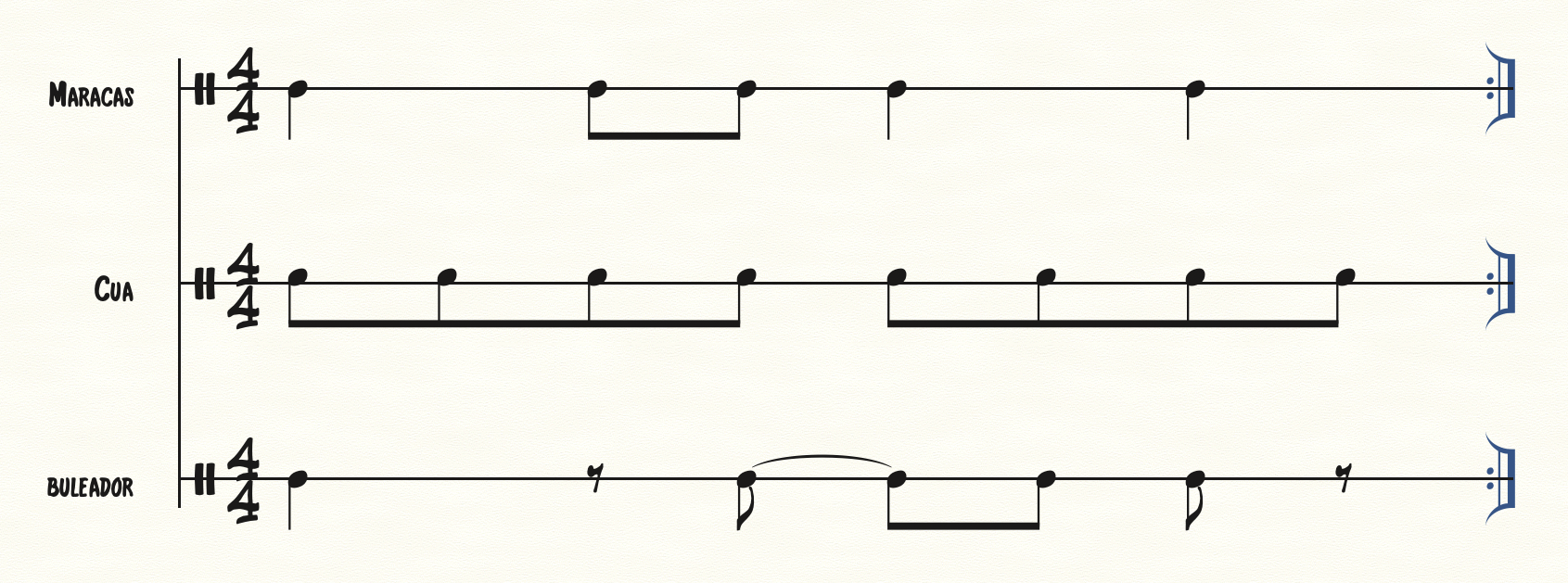

Bomba Jam!

Here are some basic rhythms played by maraca, cua, and buleador players. Divide the class into three groups (instrumental sections); once each group learns its part, they can jam together!

Bomba Jam, notation by and used with permission of Edwin E. Porras.

Bomba Vocals

The voice also has a vital part in bomba music.

- Lyrics often reflect the hardships of slave labor on sugar plantations.

-

Lyrics are usually in Spanish (sometimes Creole French), and consist of short, repetitive, rhythmic phrases.

- Historically, the lyrics were sometimes used to relay coded messages.

- Songs often use call and response form: an individual lead singer (or sometimes several) alternates with a group of people.

"Venga Ron/ Agua Tiré (medley)",

by the Parilla Family in Loiza

Listen to this example.

Do you hear these characteristics?

Bomba: African Roots

Some argue African musical influences, which are so clearly present in bomba music, have helped make this genre so popular— in Puerto Rico and internationally:

-

Call and response: the lead singer performs a melodic line and a group of singers sing back a response.

-

Collective participation: Everyone takes part in the musical performance (including the audience).

-

Polyrhythm: multiple meters are played at once (e.g., 3 against 4).

-

Syncopation: the regular metrical accent is disrupted because weak beats are stressed.

-

Improvisation: spontaneous performance, often inspired by dancing.

Attentive and Engaged Listening

Listen to this audio example (recorded in Loíza in 1967).

"Bomba," by Ensemble from Loíza Aldea (P.R.)

What African diasporic influences are most pronounced?

What instruments can you identify?

Call and Response

Collective Participation

Polyrhythm

Syncopation

Improvisation

Learning Checkpoint

- What are the three most important aspects of bomba music?

- What are the main instruments used in bomba music?

- What are the typical performance spaces for bomba music?

- What African diasporic influences are present in bomba music?

End of Component 2: Where will you go next?

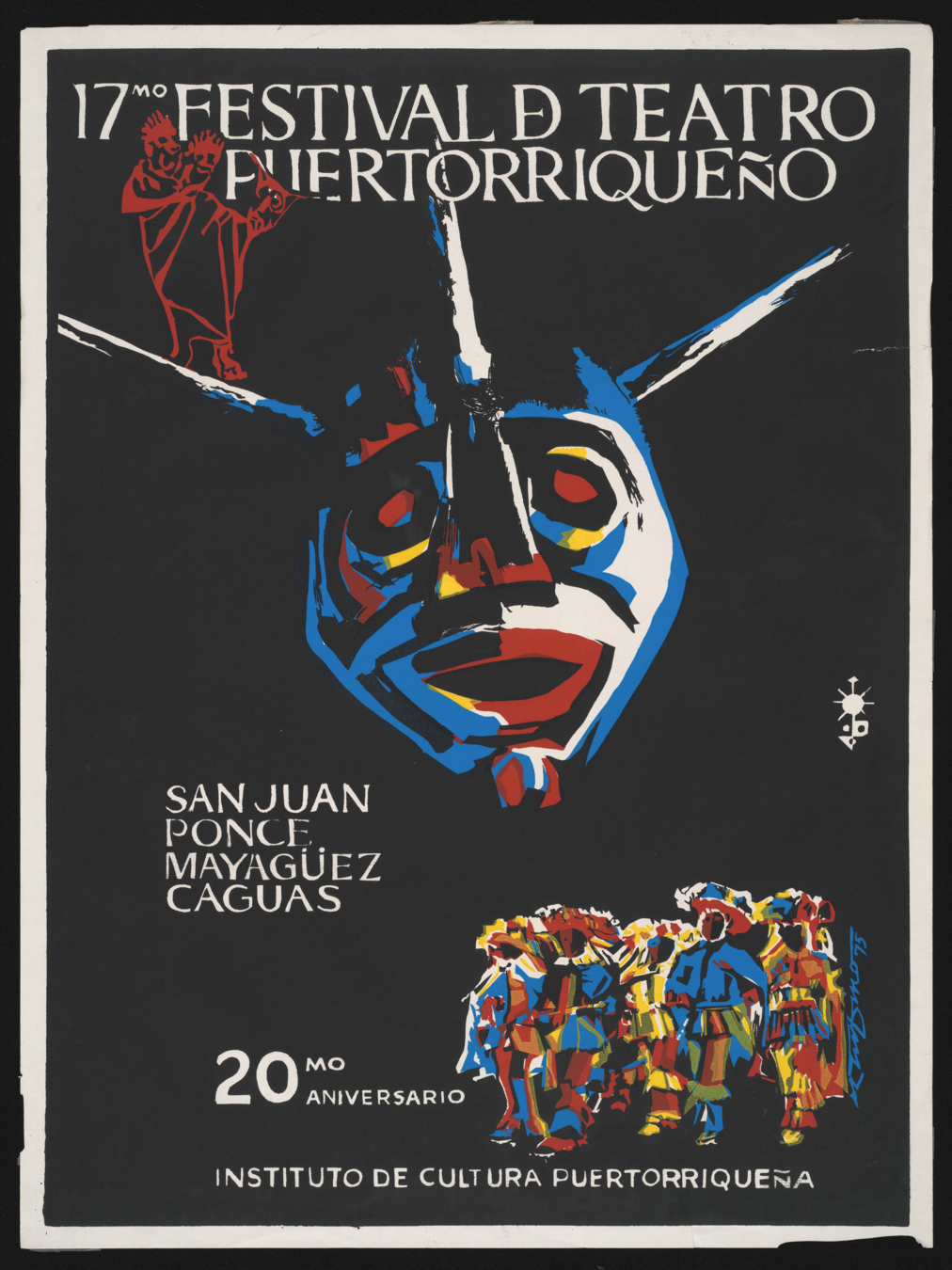

Fiesta and Bomba: Identity on Display

Component 3

20+ minutes

Vejigante and Caballero Depicted on Poster, Instituto de Cultura Puertorriqueña.

Bomba: Performance Spaces and Participants

Girl Dancing Bomba at Batey de los Ayala Loiza,(Raul Ayala singing in back row), photo by Jaime O. Bofill Calero.

Typical performance spaces for bomba music include:

- Town centers (in commmunity spaces called soberao or batey)

- Staged performances

- Fiestas and festivals

Participants are:

- Drummers

- Dancers

- Singers

- Audience members (both local and visitors)

Bomba!

Watch this bomba performance at

a Fiesta Santiago Apóstol

in Loíza's Matauri neighborhood.

What do you notice about the instrumentation, dancing, singing, and rhythms?

Toque de Bomba en el Barrio de Maturi, uploaded by Con Espiritu Utópico. Start video at 09:10.

Fiesta and Identity

In this component, we will focus on fiestas and festivals as ideal spaces for the convergence of cultural identity.

Specifically, we will explore how bomba and other cultural symbols at the Fiesta Santiago Apóstol foster the construction of collective identity that is unique to Lóiza, Puerto Rico.

Bomba at Batey de los Ayala, Loiza, photo by Jaime O. Bofill Calero.

Fiesta Santiago Apóstol: A Procession of Identities

The Fiesta Santiago Apóstol is an expression of Puerto Rico's wide identitarian make up; it is a space where identity is signaled through:

- Sound and music

- Masks and fashion

- Carnival characters

- Food

Vejigante Masks During Street Procession, by Lowell Fiet. Digital Library of the Caribbean.

Fiesta Santiago Apóstol de Loíza!

The Fiesta Santiago Apóstol de Loíza is celebrated for 10 days, from the 24th of July to the 2nd of August!

- It is an important community gathering in Loíza, a coastal town in Puerto Rico.

- It is related to the Roman Catholic Church: Masses, prayers (called novenas), weddings, and baptisms are frequent.

- People often dress up in costumes - it is a "Carnival-like" atmosphere.

Vejigante and Caballero in Loíza, by Jaime O. Bofill Calero.

Fiesta Symbols: Sound and Music

One way in which cultural identity is expressed at this festival is through the juxtaposition of musical genres:

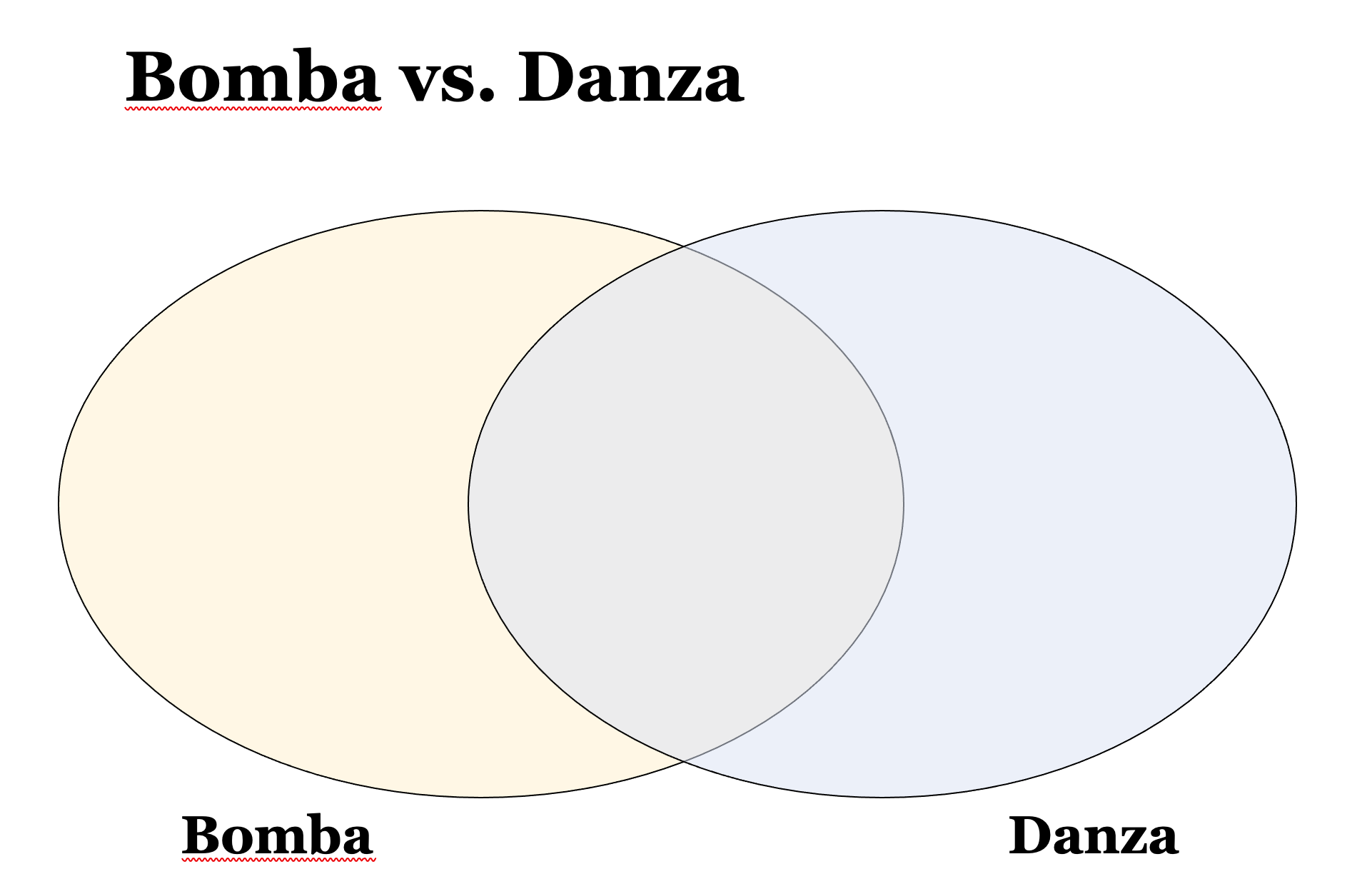

- There are two genres of Puerto Rican music that play significant, yet distinct roles in the celebration of Santiago Apóstol: Bomba and Danza.

- Though primarily known for bomba, the first and final days of the celebration and procession in Loíza are framed by solemn religious character and the performance of danza.

"Virginia" (danza), performed by musicians of Loiza during procession of Santiago Apóstol.

Fiesta Santiago Apóstol: Bomba

Bomba is generally considered African-inspired music, and therefore, represents Loiza's proud African heritage.

Carlos Ayala Seated In Front of Bomba Drum, photo by Jaime Bofill Calero.

Bomba is often played at the town's square during the festival days.

It also signifies the history of slavery on the island and represents the marginalized working class.

Fiesta Santiago Apóstol: Danza

Danza music, due to its roots in Western Europe, symbolizes propriety and sacredness with Saint James and the Catholic church.

In Puerto Rico, danza combines aspects of contradanza (classical European dance music) and Afro Caribbean elements.

Danza music is often heard during the more sacred/religious parts of the festival, such as the procession of the Santiago statues.

"Danza, Op. 33 (Porto Rico, November 1857)", composed by Louis Moreau Gottschalk, recorded by Amiram Rigai

Optional Creative Activity #1: Bomba vs. Danza

Bomba Example

Danza Example

Fiesta Symbols: Masks and Fashion

- Vejigante masks are made from coconut shells.

- They are complemented with bright-colored clothes (often green and yellow).

Vejigante masks are one of the most important symbols of the fiesta.

During the procession, people dress up in masks and costumes, representing different characters, as they follow the statues of St. James through the streets.

One of the most common costumes represents characters known as vejigantes: pagan demons with horns.

Vejigante With Three Horns, by Lowell Fiet. Digital Library of the Caribbean.

Fiesta Symbols: Masks and Fashion

Caballeros (gentlemen/cowboys) represent the protectors of Santiago.

- They fight for St. James against vejigantes (playfully) during the festival.

Vejigante and Caballero, by Jaime O. Bofill Calero.

- Viejo (old man) is a white haired character who dresses nicely and walks with a cane. He symbolizes the protectors of Saint James and "European values".

- La Loca (crazy/deranged woman) is usually a male dressed up as a lady. She wears black soot on her face, messy clothes, and has messy hair. She laughs hysterically and sweeps the ground—cleaning the path for St. James.

More Fiesta Characters

Top: La Loca "Crazy Woman". Bottom: "Viejo" Rubber and Plastic Mask. Photos by Lowell Fiet, Digital Library of the Caribbean.

Masks and symbols at Fiesta Santiago Apóstol signal a variety of class, gender, and religious identities.

Optional Creative Activity #2: Make a Mask!

Carnival Mask, by Leonardo Pagán. National Museum of American History.

The National Museum of American History has put together a guide that can help you make your own vejigante mask.

Download the instructions (pdf), gather your materials, and get started!

Fiesta Symbols: Food

Food is extremely important at Fiesta Santiago Apóstol (and any type of Puerto Rican celebration)!

Some common fiesta foods include: mofongo, bacalaitos, casabe, and arepas de coco.

Above: Mofongo with Shredded Pork and Pork Cracklings, Ramonita's, by Garrett Ziegler. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0, via Flickr. Left: Casabe, by Luis Ovalles. CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Friends of Loíza: Fiesta and Diaspora

- Friends of Loíza are people from other places who join in this celebration.

- Hijos Ausentes (absent sons) are people who have moved away from Loíza or those born in the US, who gather to celebrate the Fiesta of Santiago Apóstol.

- New York City and Philadelphia both hold celebrations of the Fiesta Santiago Apostol de Loíza.

- These celebrations help to preserve Puerto Rican traditions in an international context.

Regardless of birthplace, everyone is welcome to celebrate this fiesta!

Learning Checkpoint

- Why is Fiesta Santiago Apóstol de Loíza a good example of cultural convergence?

- What are some cultural symbols that are "on display" at Fiesta Santiago Apóstol de Loíza?

End of Component 3 and Lesson 6: Where will you go next?

Lesson 6 Media Credits

Audio courtesy of

Smithsonian Folkways Recordings

Video courtesy of

Smithsonian Folklife Festival

Smithsonian Music

Jaime O. Bofill Calero

Images courtesy of

Smithsonian Folkways Recordings

University of Texas at Austin, PCLP Map Collection

Lowell Fiet, University of Puerto Rico

Jaime O. Bofill Calero

National Museum of American History

Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage

Instituto de Cultura Puertorriqueña

New Jersey State Council on the Arts

© 2021 Smithsonian Institution. Personal, educational, and non-commercial uses allowed; commercial rights reserved. See Smithsonian terms of use for more information.

This project received Federal support from the ... administered by the Smithsonian ....

For full bibliography and media credits, see Lesson 6 landing page.