Listen What I Gotta Say: Women in the Blues

Lesson 3

Melting Pot: Becoming the Blues

6th grade–8th grade

In what ways did the mixing of cultural influences (especially characteristics from African and European musical styles) affect the creation of the “blues”?

The Story of the Jubilee Singers, Unknown photographer. National Portrait Gallery.

The question to consider in this lesson is . . .

Melting Pot: Becoming the Blues

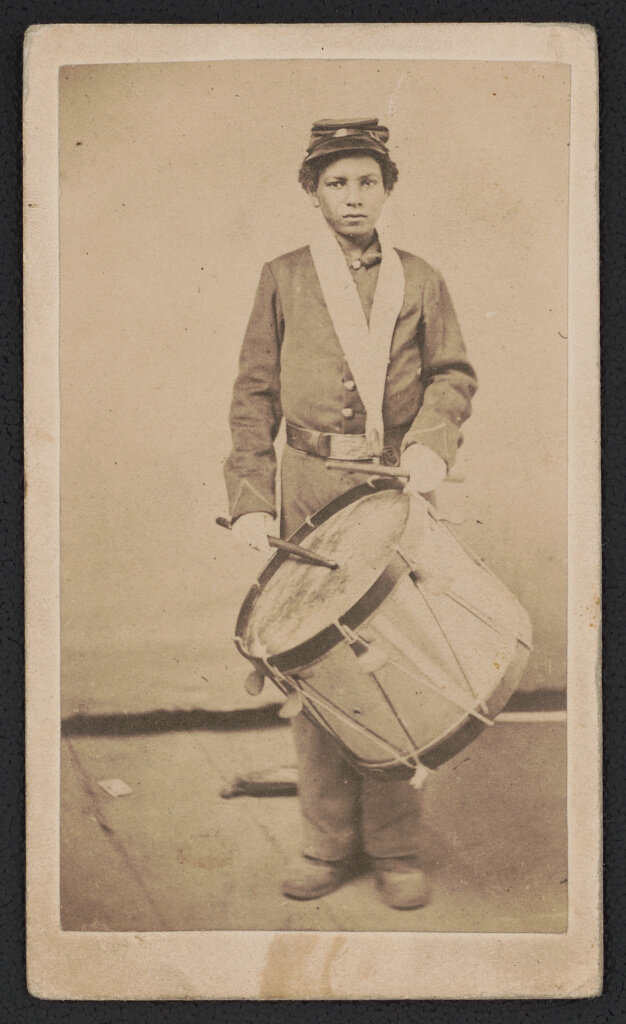

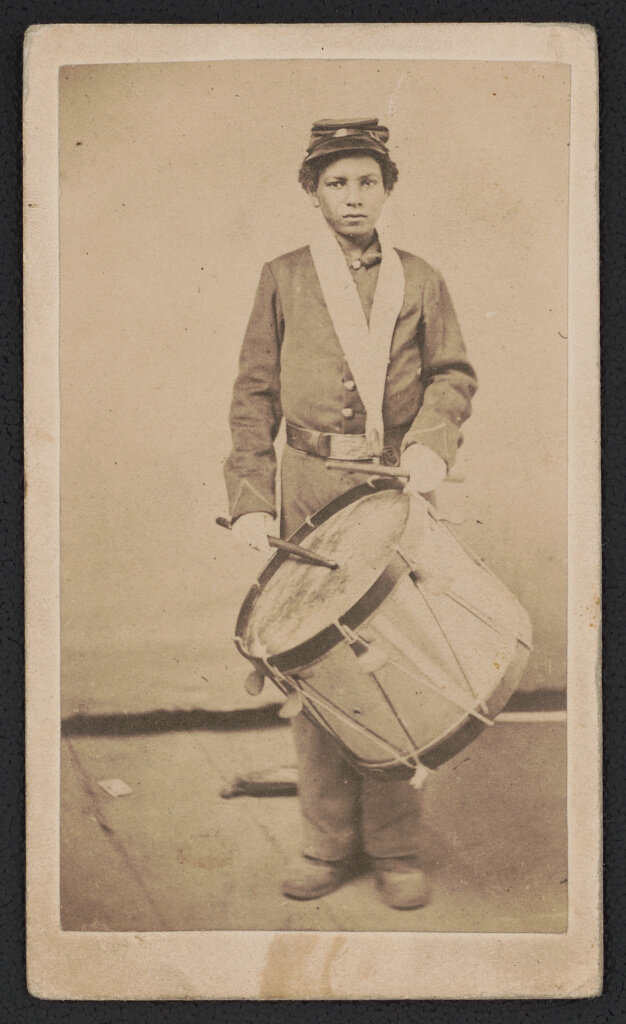

Taylor, young drummer boy for 78th Colored Troops (USCT) Infantry, in uniform with drum, Unknown Artist. Library of Congress.

Before the Blues: Spirituals

Component 1

30 minutes

Fisk Jubilee Singers, Unknown photographer. National Portrait Gallery.

The Melting Pot of America

From the 16th-19th centuries, millions of people from Africa were forced from their homes and families and taken to the Americas.

While in the Americas, these enslaved Africans began to blend their music culture with the new music culture they were in.

Melting Pot: Becoming the Blues

Over time, new musical forms emerged (e.g. ring shouts, field hollers, work songs, spirituals, gospel, ragtime, blues, etc.)

Because this process happened over centuries, it is difficult to identify which musical practices were of African origin, local, Indigenous, or European influence.

Attentive Listening

Listen to a short excerpt (30-45 seconds) from this audio recording.

As you listen, think about this guiding question:

What kind of music is this?

Spirituals

This song, entitled “Rock Chariot, I Told You to Rock,” is an example of an African-American spiritual.

This version was recorded in the 1950s in rural Alabama.

Road Leading To Small Cabin, Alabama, by Harold Courlander. Folkways Records.

About Spirituals

In the American South during the time of slavery, enslaved Blacks had little mobility outside of the plantation and had little time for social activities as they worked from daybreak to sundown—except on Sundays and holidays.

On their Sundays, they developed a worship style independent of the white Protestant music tradition. They modified traditional Protestant hymns in ways that allowed them to express their frustrations and emotions.

These modified hymns are called spirituals.

Text

Listen Again...

What do you think the performance purpose of spirituals were?

Negro Folk Music of Alabama, Vol. 2: Religious Music, by Ronald Clyne. Folkways Records.

Spirituals: Performance Context

Red Willie Smith with Guitar, by Harold Courlander. Folkways Records.

Spirituals were constructed of sacred text and were originally for Protestant church worship.

However, spirituals were also quickly adapted for use while laboring in the fields to build community among the enslaved workers.

Spirituals: More History

During the mid-19th century, spirituals were also used to relay coded messages about the Underground Railroad (e.g. “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot”).

After the Civil War, arranged spirituals grew in popularity and choir ensembles from historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) toured the United States and Europe performing spirituals on the concert stage.

The Jubilee Singers (originated in 1871) is a vocal ensemble comprised of students from Fisk University (HBU in Nashville, TN).

Attentive Listening: Rhythm

Listen to several additional short excerpts from this recording (approx. 30-45 seconds each).

Each time you listen, think about a new guiding question:

What do you notice about the rhythm?

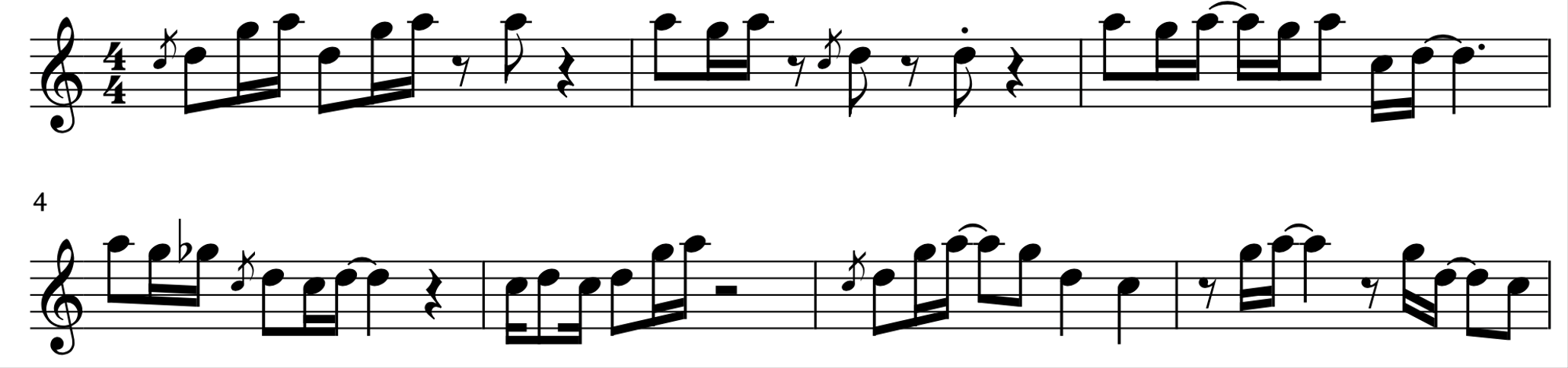

Generally Speaking .....

"Swing"

The lead singer begins the phrase before the downbeat.

This is known as the anacrusis: a note or sequence of notes, or a motif that precedes the first downbeat in a musical phrase.

This emphasis on the off-beat creates a “swing” feel.

“Swing” feel occurs when the beat is divided into two parts, and the former part is longer and more accented than the latter.

long

short

long

short

long

short

4

4

Generally Speaking .....

Attentive Listening: Form/Structure

What do you notice about the form/structure of this song?

Generally Speaking .....

Call and Response

Listen again and follow along with the lyrics:

-

The male lead begins the phrase, and the choir offers the response:

-

Lead: Rock, Chariot, I told you to rock!

-

Chorus: Judgement goin’ to find me!

-

You will also notice that the lead singer lines out the verse so that the congregation knows and can join in.

Rock Chariot, I Told You to Rock, trad., layout by Harold Courlander. Folkways Records.

Generally Speaking .....

Attentive Listening: Style & Melody

What do you notice about the vocal style?

What do you notice about the melody?

Generally Speaking .....

Vocal Style & Melody

-

The singers use relaxed voices.

-

The singers use feeling in their singing.

-

The vocalists use bent pitches

Vocal Style

-

There is not a lot of variation

-

The range of pitches used is narrow

...anything else?

Melody

Generally Speaking .....

A Musical Melting Pot

The “spiritual” is an example of a musical form that developed as Black Americans in the southern part of the country blended musical characteristics from various African traditions with European and local influences (song forms and religious influences).

Over time, spirituals influenced the development of other musical genres created by Black Americans, such as gospel and the blues.

Generally Speaking .....

Spirituals and the Blues

Improvisation

Vocal Style

-

The performance style and lyrical content of spirituals can fluctuate depending on the performer. Verses can be added, rearranged, or left out.

-

Improvised singing and playing is common in the blues.

Form

- Call and response form is commonly present in spirituals due to its function in creating communal worship experiences.

- The use of call and response characterizes the musical relationship between the vocalist and instruments in blues music.

- Especially through ululations (a howling or wailing sound), spirituals express feelings and emotions, much like emotions are demonstrated in the blues.

Learning Checkpoint

What are some common characteristics of spirituals?

How did they influence the development of the blues?

End of Component 1: Where will you go next?

Combining Influences: Fife and Drum

Component 2

30 minutes

Ed Young Southern Fife Drum Corps, by Diana Jo Davies. Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives and Collections, Smithsonian Institution.

Combining Influences: Fife and Drum

Yankee Volunteers Marching into Dixie in 1862, by John Henry Bufford. National Museum of American History.

The blues is like a sonic melting pot, incorporating music traditions from many areas.

One tradition that many enslaved Africans learned in the Americas that influenced certain types of the blues was called Fife and Drum.

Fife and Drum: Historical Context

In early American history, enslaved Africans were recruited to fight in battles and wars, such as the Revolutionary War.

While forced to give their lives, the militia did not always trust giving weaponry to enslaved Africans. They were instead often used for military bands, such as the fife and drum corps.

Boys in Uniform and with Instruments, Marching in Fife and Drum Corps 1904, by Helen Hamilton Gardener. National Museum of Natural History

Fife as Communication

The practice of using fifes as a military signaling instrument is an old practice.

In Europe, fifes were used to signal commands on the battlefield, hours of duty, formations, and to lift morale.

Text

Fife and Drum in the Military

The Fife and Drum Corps tradition continued in the American military during and after the Revolutionary War.

American Bicentennial: Fifer, United States Postal Service. National Postal Museum.

After the Revolutionary War...

Unfortunately, white Americans continued to enslave Africans and their children, and drumming became prohibited.

Owners of enslaved people were fearful that enslaved Africans would use coded messages in their drumming patterns to incite rebellions and uprisings among other enslaved Africans.

The rhythms and detail patterns enslaved people learned within the fife and drum corps were not forgotten, however. Instead, they were transferred to other instruments that were permitted.

During the Civil War...

. . . enslaved Africans were once again recruited for fife and drum bands to aid soldiers.

After the Civil War (1865), fife and drum ensembles persisted in the American South, though no longer affiliated with battle.

Musical Fusions

Once the Civil War was over, Black Americans took their knowledge from fife and drum bands and fused it with performance styles and practices familiar to them:

Union Regimental Drum Corps from the American Civil War, Unknown artist, PD-US-expired, via Wikimedia Commons.

- improvisation

- interlocking patterns or polyrhythms

- blue notes

- call and response

- ululations

Fife and Drum Blues

The interesting combination of musical sounds that emerged became known as the Fife and Drum Blues.

Listen to part of “Shimmy She Wobble” by Napoleon Strickland, Otha Turner and the Como Band.

Napoleon Strickland, Fife, Unidentified Girl-Bass Drum, and Otha Turner, Drums, by Chris Strachwitz. Arhoolie Records.

Compare and Contrast

Listen to short excerpts from:

- “Shimmy She Wobble” by Napoleon Strickland, Otha Turner and the Como Band (Fife and Drum Blues)

- “Processional Easter-Saturday” by the Orangemen of Ulster (Fife and Drum Corps from Northern Ireland)

As you listen, identify similarities and differences between these styles.

“Processional Easter-Saturday”

“Shimmy She Wobble”

Discuss...

How are they different?

How are these pieces similar?

Do you hear any elements of the “blues” in “Shimmy She Wobble?”

“Shimmy She Wobble”

“Processional Easter-Saturday”

Optional Extension Activity: Research

Do we still have Fife and Drum Corps today?

If so, what role do they have in the military today?

Learning Checkpoint

What is the historical context of Fife and Drum Corps?

How and why did the Fife and Drum Blues develop?

End of Component 2: Where will you go next?

Fife and Drum: A New Generation

Component 3

30 minutes

The Rising Star Fife and Drum Band @ Blues Rules, by Christopher Losberger, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0, via Flickr.

Watch this video...

As you watch, think about the following guiding questions:

Who are the performers?

What type of music are they playing?

Rising Star Fife & Drum Band, by Kelsey Michael, Marinna Guzy, Michael Headley, and David Barnes. Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage

Fife and Drum: A New Generation

Fife and drum music arrived in America’s Deep South in the 18th century with military marching bands .

The instruments (fife and drum) and elements of the style were woven into the musical traditions of enslaved Africans.

Today, this tradition (which has influenced the blues) lives on in the work of Shardé Thomas who leads the Rising Star Fife and Drum Band.

Shardé Thomas at the 2012 Smithsonian Folklife Festival, video still provided by Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives and Collections, Smithsonian Institution. .

Watch the video again (broken into several short excerpts). Each time you listen, discuss a new guiding question:

Attentive Listening

Which instruments do you hear?

What do you notice about Shardé’s singing style?

What do you notice about the song structure?

What do the lyrics mean?

Shardé Thomas

Shardé Thomas is the granddaughter of Otha Turner, the Mississippi fife master who founded the Rising Star Fife and Drum Band around 1907.

Otha Turner was one of the performers on “Shimmy She Wobble” (Lesson 3, Component 2).

About the Video

What do you notice about Shardé’s singing style?

Shardé’s vocal style resembles that of a blues singer

Which instruments do you hear?

Bass drum, snare drum, fife, and voice

What do the lyrics mean?

The lyrics are centered on feelings and share a narrative (similar to many blues songs)

What do you notice about the song structure?

The snare and bass drum parts seem to “interlock” (polyrhythm)

The song structure has some similarities to the blues (call and response).

1

2

3

4

Make Music!

Shardé Thomas learned to play the fife from her grandfather as a child (Otha Turner).

In the next activity, you will have the opportunity to learn the melody and rhythm that she learned growing up!

- Start by listening to the beginning of the video several more times.

- When you are ready, hum or pat along.

Make Music!

Minor Pentatonic Scale

The melody you just heard primarily uses the d minor pentatonic scale (which is composed of five notes).

- Can you sing the minor pentatonic scale using a neutral syllable (like loo or la)?

- Can you sing the minor pentatonic scale using solfège (do, me, fa, sol, te)?

- Can you sing the d minor pentatonic scale using note names (d, f, g, a, c)?

D minor pentatonic scale

d

f

g

a

c

Play it on Instruments

Next, practice playing this minor pentatonic scale on an instrument:

- Keyboard, Orff instruments, ukulele, and/or a variety of wind instruments (especially flute or recorder) will work well for this activity

- Remember, the notes of this minor pentatonic scale are: d, f, g, a, c

D minor pentatonic scale

d

f

g

a

c

Enactive Listening

Next, you will learn this melody by ear on your instrument.

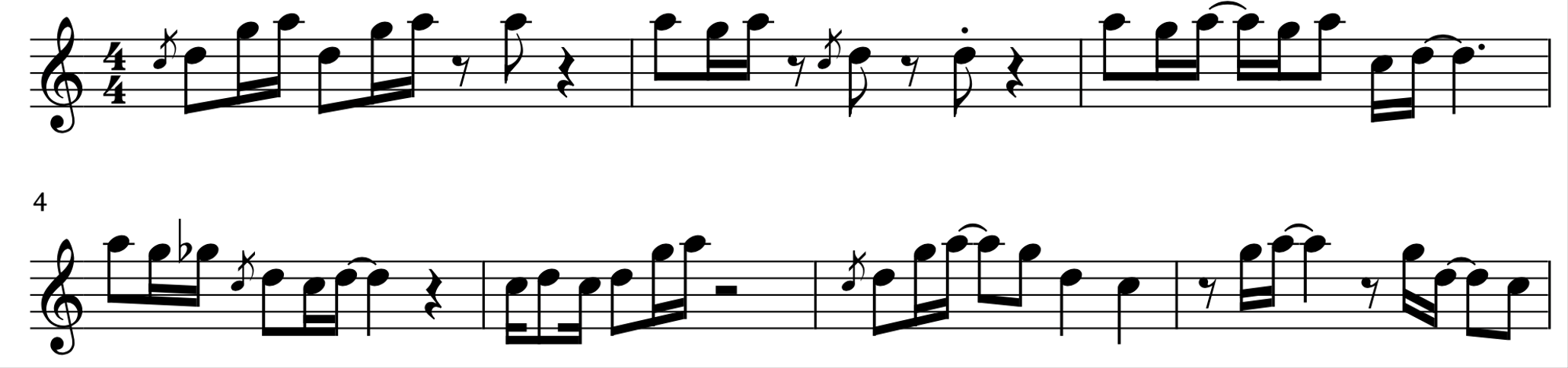

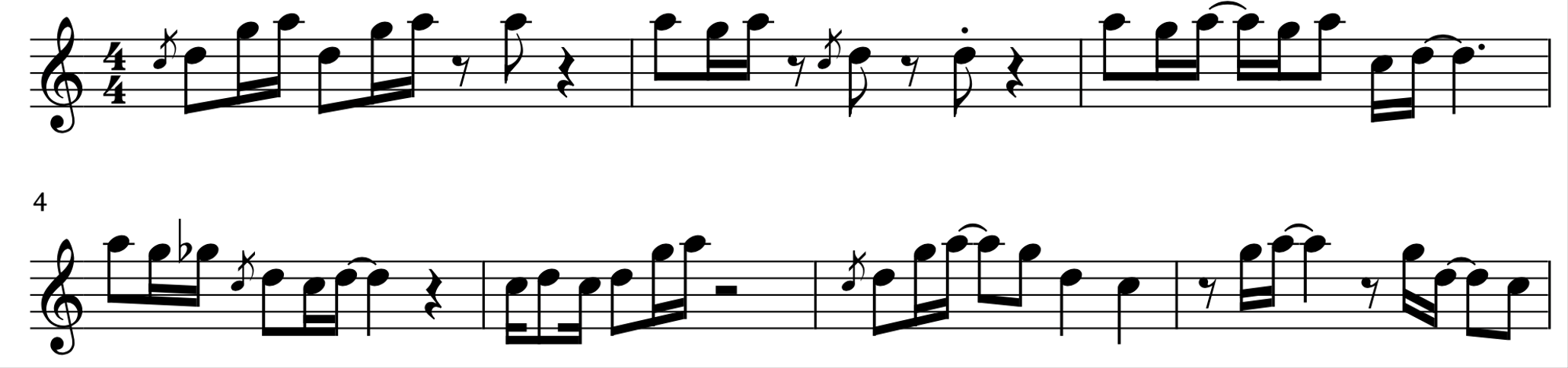

Learn the Rhythm

Next, you will learn an accompanying rhythmic ostinato pattern

-

When you are ready, play it on an instrument (drum, if possible)

4

4

Optional Extension Activities

You’ll notice that the melody does not resolve or seem to end. . . it seems to be missing a note.

- Improvise and play around on your instrument to find the final concluding note.

- This will be your first step in learning improvisation - use your ears.

Optional Extension Activities

Put it all together!

-

Some students can play the melody while others play the rhythm (you can also add a lower drum sound on the off-beats)

-

Consider adding the grace notes and the accidental in measure 4 (especially if students are playing a wind instrument)

Optional Extension: Improvisation

Did you know that many blues musicians use the minor pentatonic scale as they create improvised solos?

-

Practice using the notes in this scale to create your own “riffs” and/or improvised solos on your instrument

D minor pentatonic scale

d

f

g

a

c

Learning Checkpoint

- In what ways did Shardé Thomas’s performance resemble the blues?

- Why is the minor pentatonic scale useful when performing the blues?

Lesson 3 Media Credits

Audio courtesy of

Smithsonian Folkways Recordings

Video courtesy of

Smithsonian Folkways Recordings

Images courtesy of

The Arhoolie Foundation

Joseph A. Rosen

National Museum of American History

National Portrait Gallery

Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives and Collections

Smithsonian Folkways

United States Postal Service

© 2022 Smithsonian Institution. Personal, educational, and non-commercial uses allowed; commercial rights reserved. See Smithsonian terms of use for more information.

This Lesson was funded in part by the Grammy Museum Grant and the Smithsonian Youth Access Grants Program, with support from the Society for Ethnomusicology and the National Association for Music Education.

For full bibliography and media credits, see Lesson 3 landing page.

End of Component 3: Where will you go next?

Continue to Lesson 4:

Standardizing the Blues