Listen What I Gotta Say: Women in the Blues

Lesson Hub 10:

I Got Something to Say: Blues Lyrics and Storytelling

What types of stories do blues musicians tell?

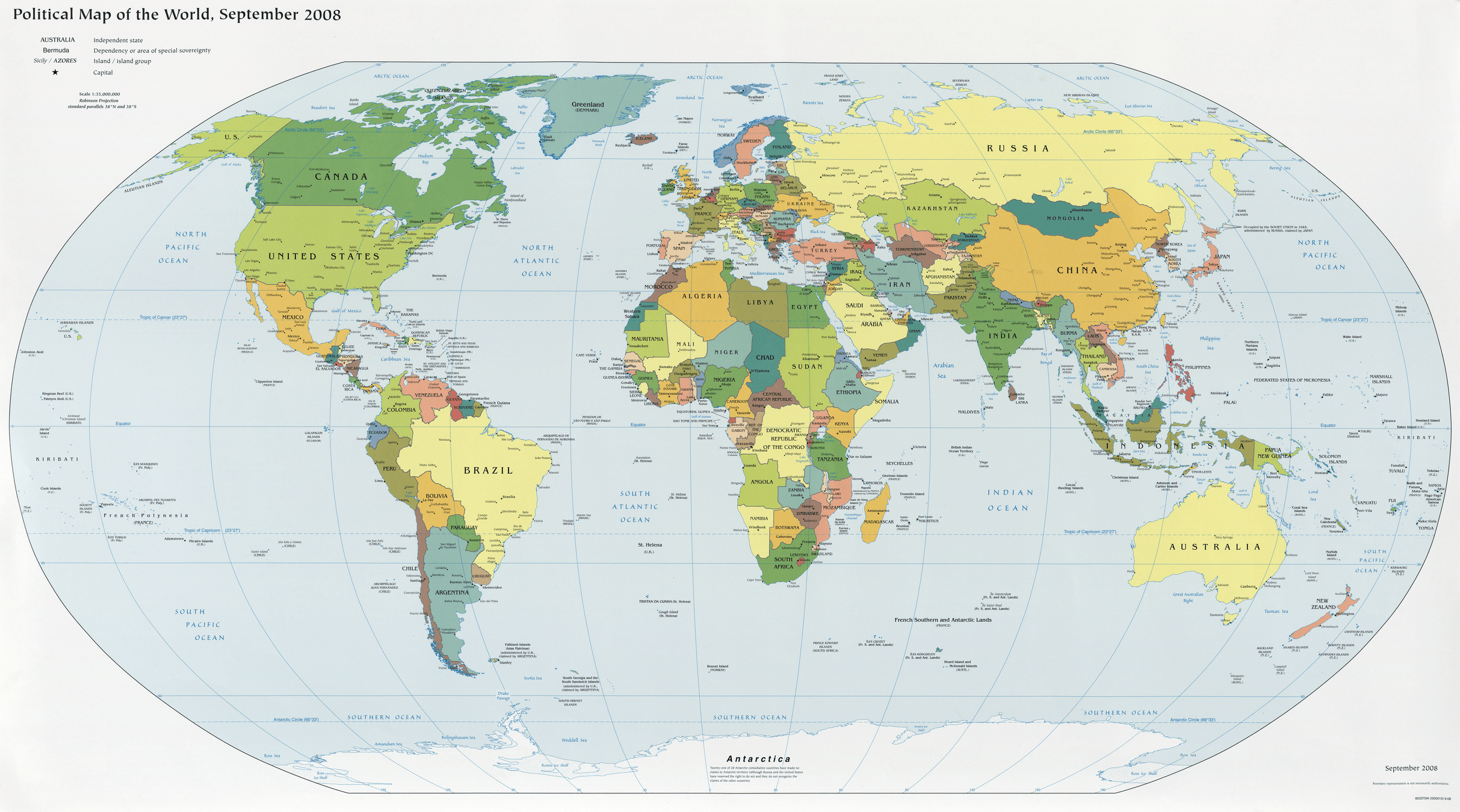

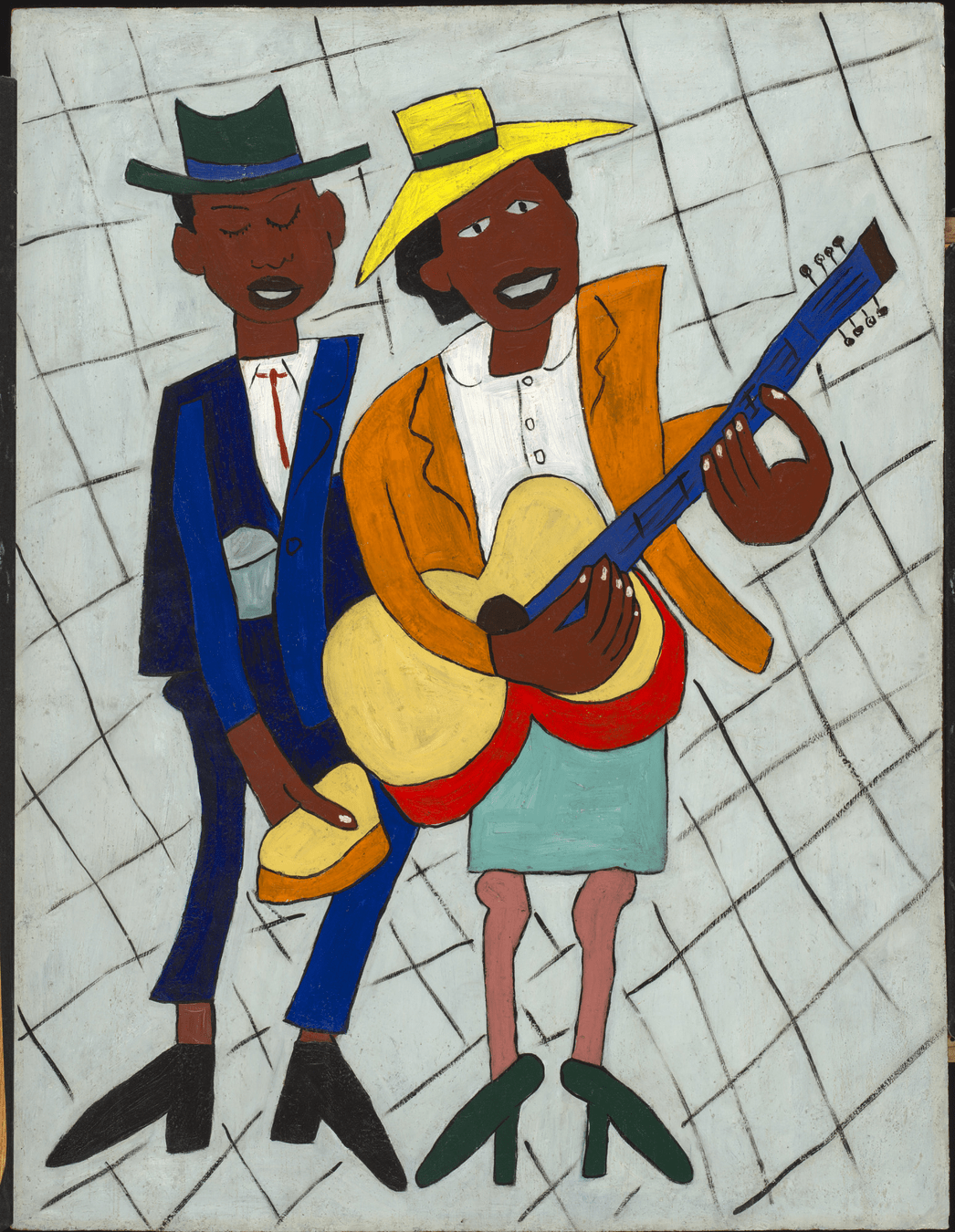

Blind Musician, by William H. Johnson. Smithsonian American Art Museum.

The question to consider in this lesson is . . .

I Got Something to Say: Blues Lyrics and Storytelling

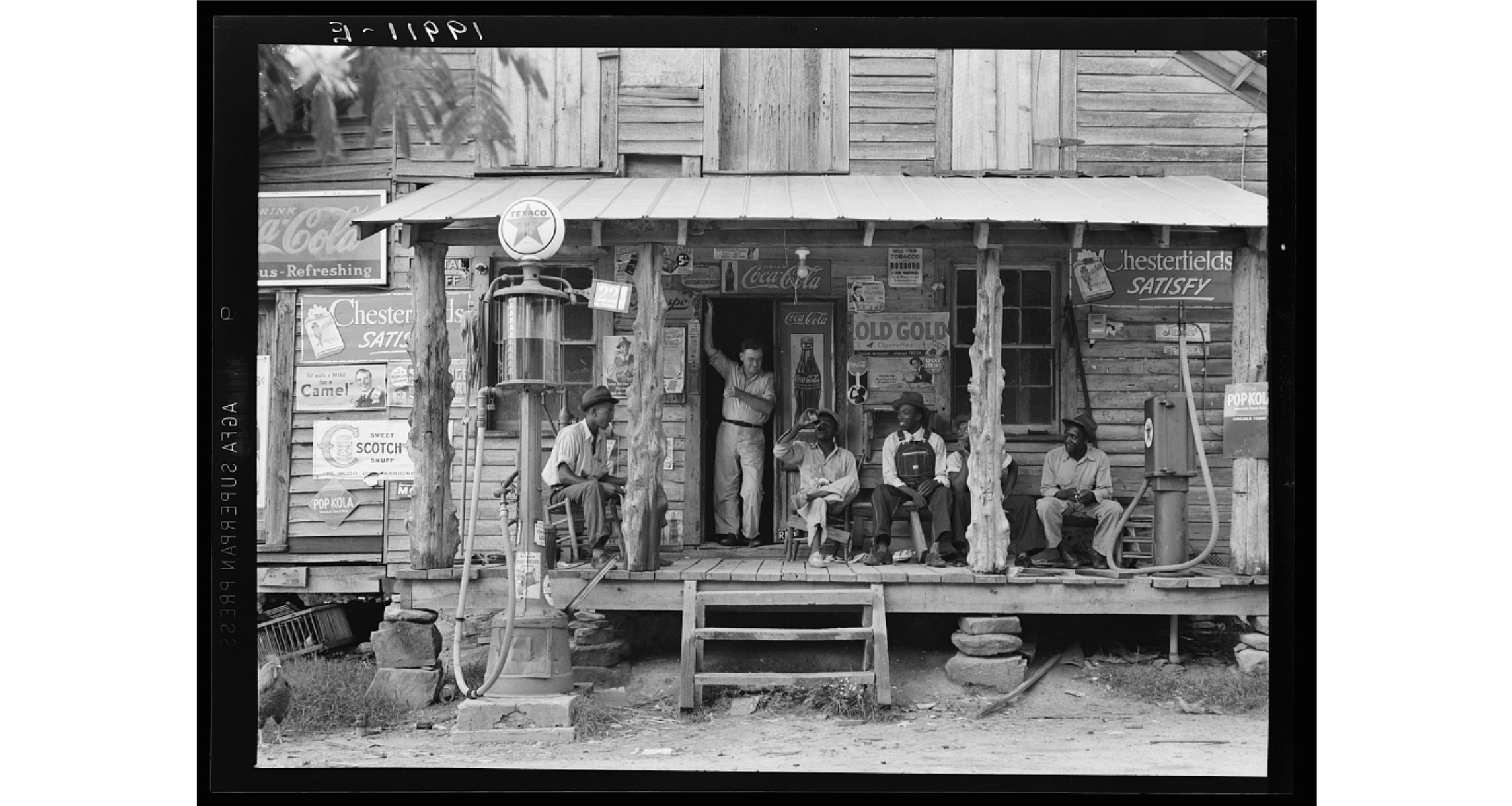

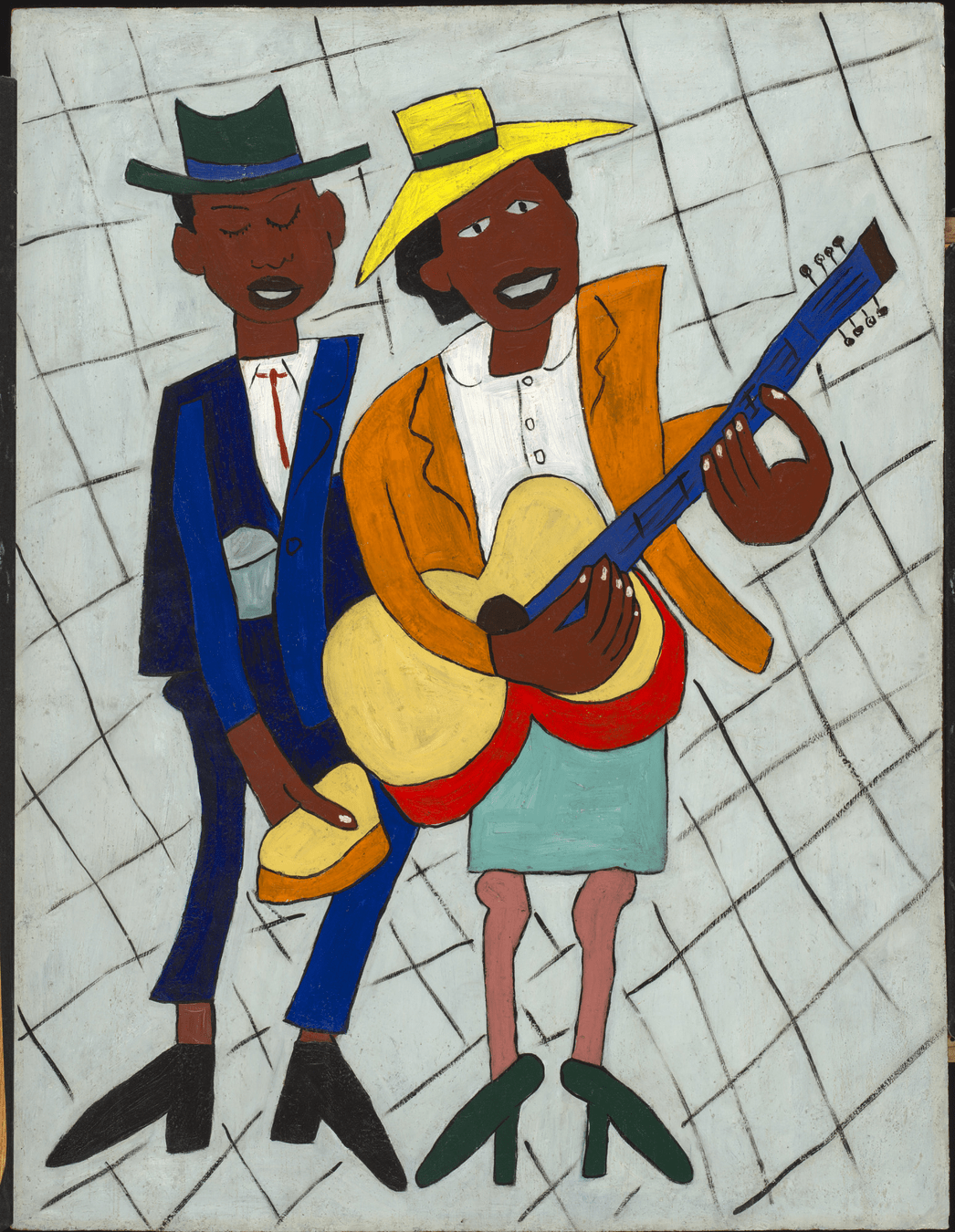

Country Store on Dirt Road, Gordontown, North Carolina, by Dorothea Lange. Library of Congress.

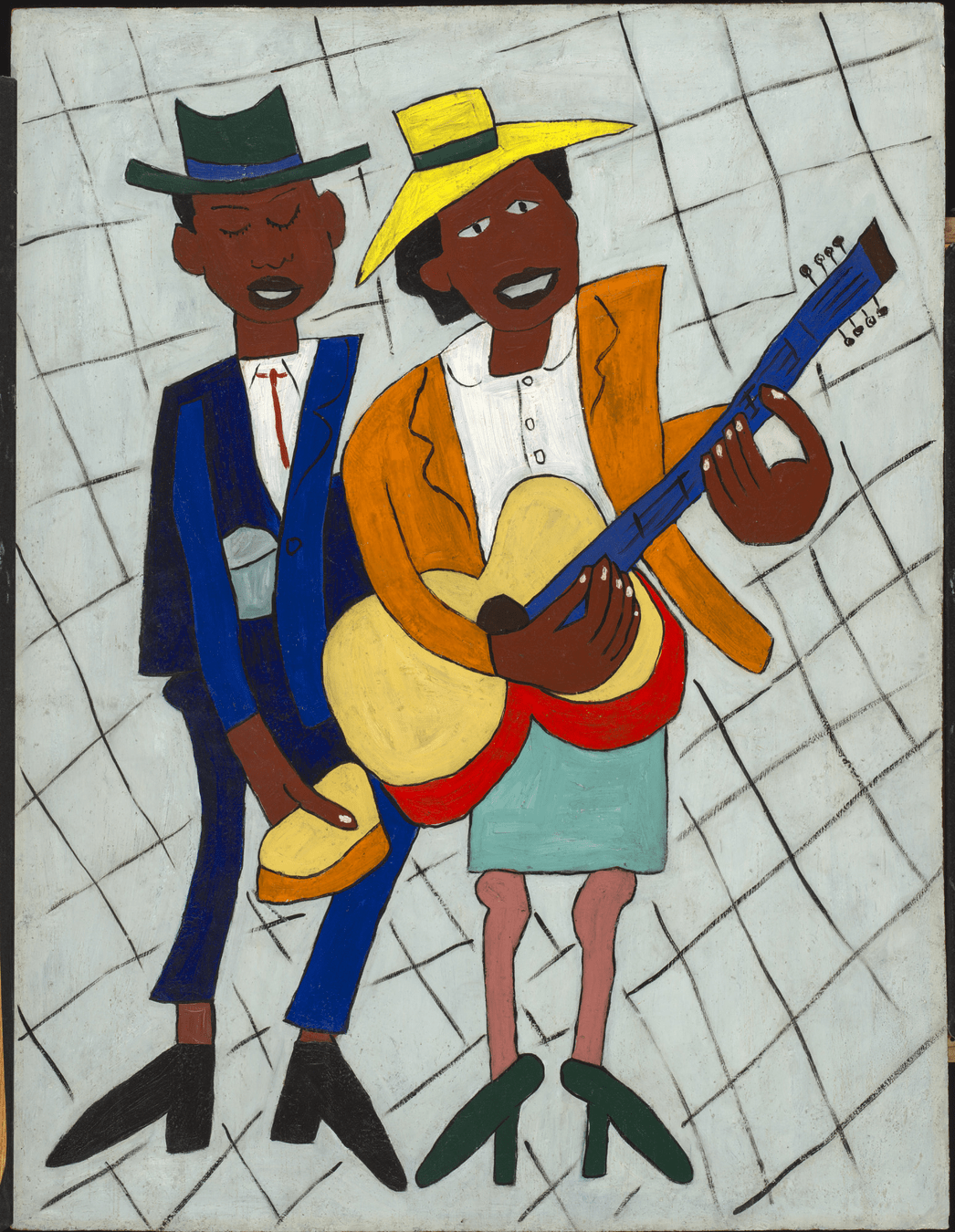

Shifting Landscapes: Blues Lyrics from the Countryside to the City

Path 1

30+ minutes

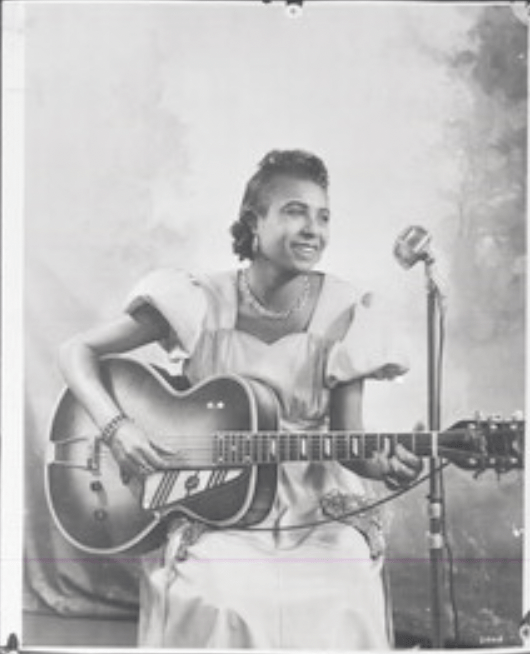

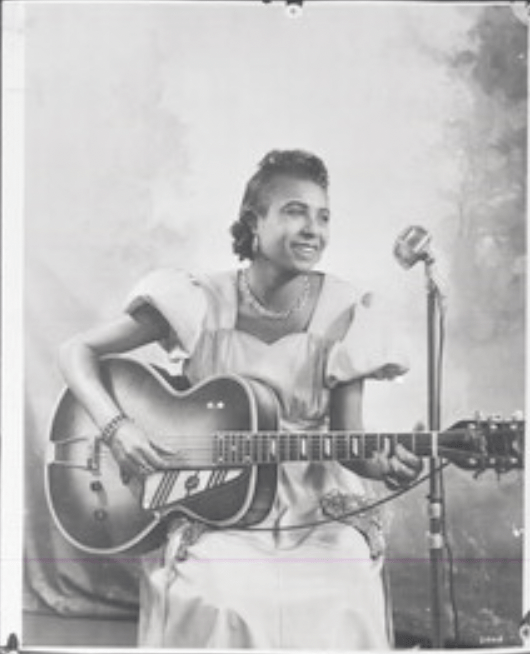

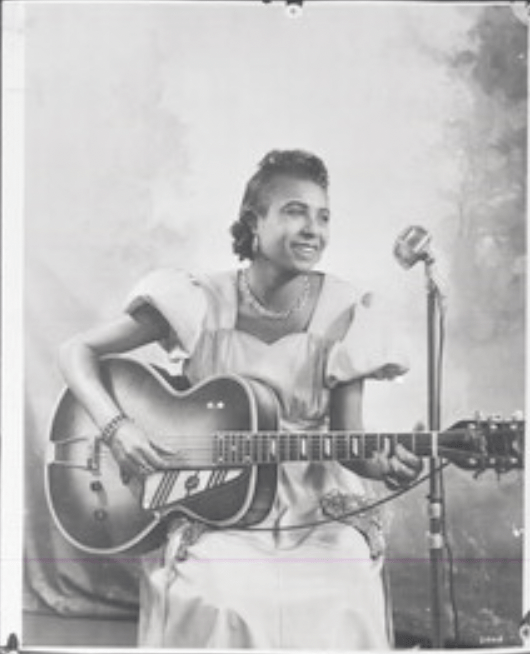

Memphis Minnie, by Duncan P. Schiedt. National Musuem of American History.

Blues Lyrics

Big Mama Thornton at Coast Recorders, San Francisco, CA, © Jim Marshall Photography LLC.

Topics of Blues Stories

Can you think of possible topics for blues songs?

Love lost

Moving

Anger

Jealousy

Work

The roots of storytelling in the blues ...

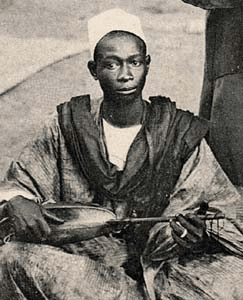

... can be traced back to Africa.

Many African cultures have a history of storytelling.

Storytelling musicians called griots traveled (and still travel) from place to place - singing stories, praises, and often the history of a kingdom.

African Griot, unknown photographer, PD-old, via Wikimedia Commons.

Historical Storytelling Through Music

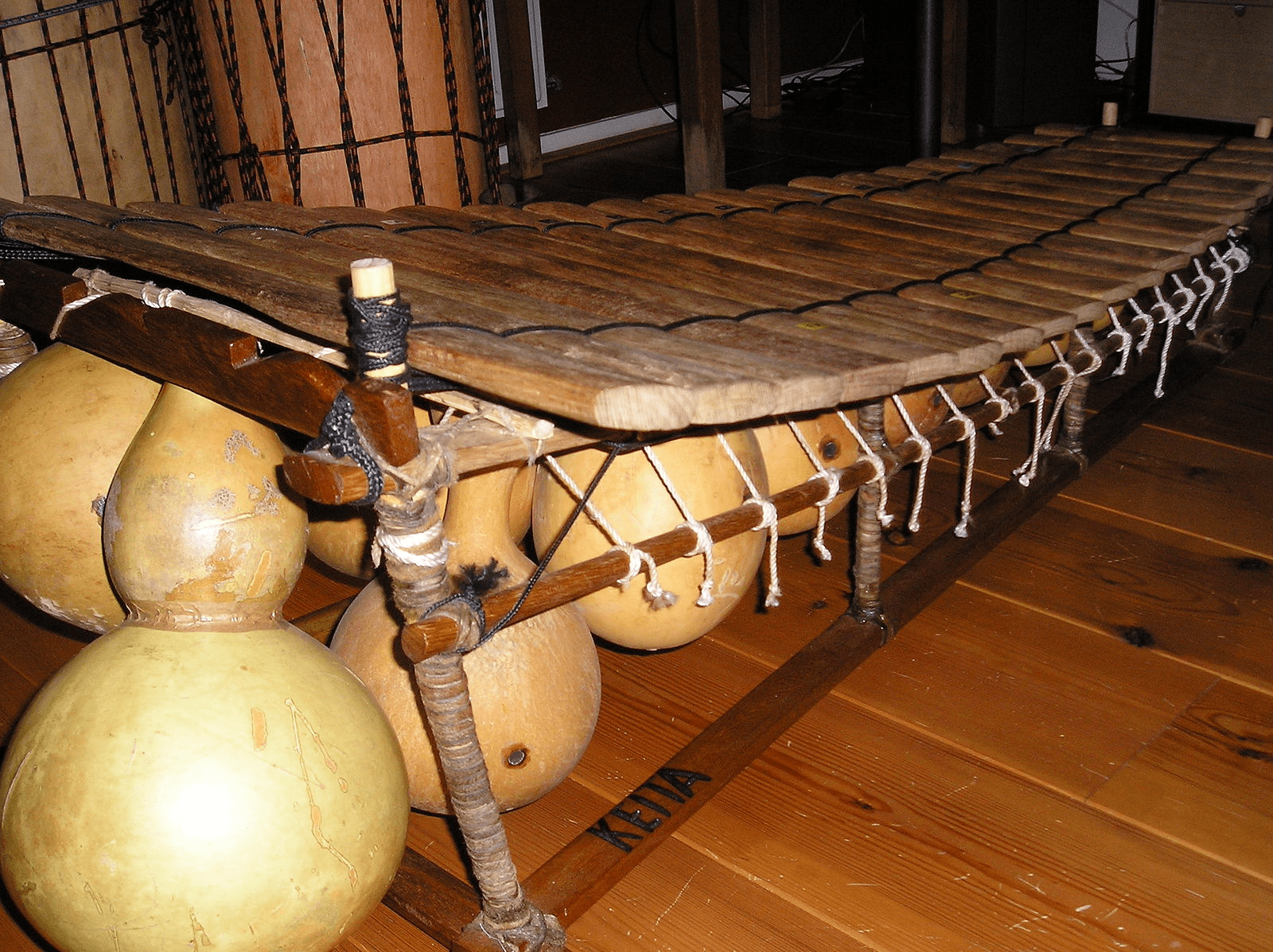

Listen to an excerpt from a song called"Toolongjong"—performed by Alhaji Falbala Kanuteh—who is singing and accompanying himself on the balafon.

West African Balafon, Redmedea. CC-BY-SA-3.0-migrated, via Wikimedia Commons.

Political World Map, by U.S. Central Intelligence Agency. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Changing Lyrics for Changing Conditions

This long history of storytelling was foundational to the development of blues music in the United States during the 19th and 20th centuries.

How do you think blues lyrics changed as conditions changed for African Americans?

Africa Continent Sketch, by Danielle Nalangan. Smithsonian Folkways Recordings. King and Anderson Plantation, Clarksdale, Mississippi Delta, by Marion Post Wolcott. Library of Congress.

Generally Speaking .....

Country Blues

Solo performer

Acoustic instrumentation

Lyrics about rural life

"Low Down Rounder's Blues," by Peg Leg Howell

Generally Speaking .....

Attentive Listening: "One Dime Blues"

Solo performer

Acoustic instrumentation

Lyrics about rural life

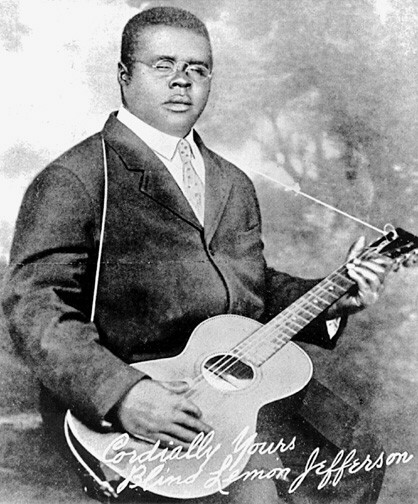

In 1927, Blind Lemon Jefferson recorded this country blues tune, called "One Dime Blues".

Blind Lemon Jefferson, unknown photographer. PD US no notice, via Wikimedia Commons.

I'm broke and I ain't got a dime.

I'm broke and I ain't got a dime.

I'm broke and ain't got a dime.

Everybody gets in hard luck sometime.

You want your friend to be bad like Jesse James?

You want your friend to be bad like Jesse James?

You want your friend to be bad like Jesse James?

Just give'm a six shooter and highway some passenger train.

Lyrics of "One Dime Blues" by Blind Lemon Jefferson

I was standin' on East Cairo Street one day.

I was standin’ on East Cairo Street one day.

Standing on East Cairo Street one day.

One dime was all I had.

Mama, don't treat your daughter mean.

Mama, don't treat your daughter mean.

Mama, don't treat your daughter mean.

That's the meanest woman a man most ever seen.

[Verse 1]

[Verse 2]

[Verse 3]

[Verse 4]

[Guitar Solo]

Women in the Blues: Etta Baker

Etta Baker, a blues woman with African American, Native American, and European American heritage is credited with popularizing this song.

Etta's version of "One Dime Blues" is purely instrumental (no lyrics). She uses a style of blues that originated in the Appalachian mountain region, called the Piedmont Blues.

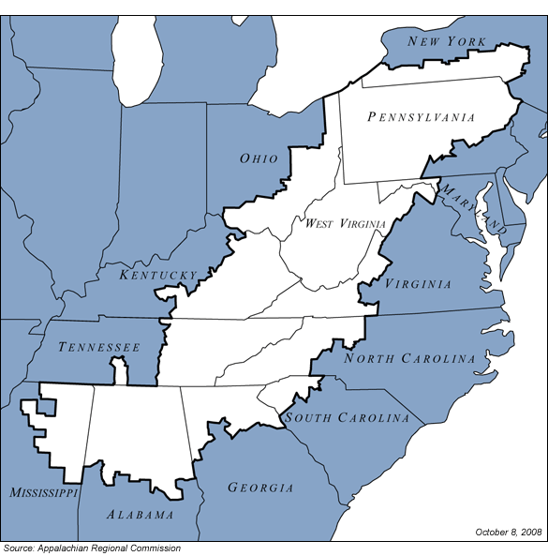

The Appalachian Region Map, courtesy of the Appalachian Regional Commision.

"One Dime Blues," by Etta Baker

Etta Baker, by David Holt. The Etta Baker Project.

The Great Migration

People began to migrate to larger cities further north, searching for better paying jobs and fleeing the Black Codes and Jim Crow laws of the south.

During the early part of the 20th century, many Black southerners faced oppressive conditions and had very few economic opportunities.

Migratory Agricultural Workers on Route 27, by Jack Delano. Library of Congress.

Urban Blues

15 Down Home Urban Blues Classics, by Wayne Pope and Dix Bruce. Arhoolie Records.

As the day-to-day situations of life changed, the blues changed too.

Some of these changes included:

-

More instruments and performers

-

Different venues (clubs vs. informal gatherings)

-

Amplification and electric instruments

Generally Speaking .....

Attentive Listening: "Hold Me Blues"

Listen to an excerpt from "Hold Me Blues," by Memphis Minnie.

How many / which instruments do you hear?

Are they acoustic or electric?

Lyrics of "Hold Me Blues" by Memphis Minnie

If he holds me in his arms, whisper darling, oh what a thrill;

If he holds me in his arms, whisper darling, oh what a thrill;

'cause I live the life I love and I love the life I live.

Well, he served two years in the Army ... across the sea;

But he would knock me cold when he would write to me.

'Cause he holds me, whispers darling, oh what a thrill;

'cause I live the life I love and I sure love the life I live.

Now he give me a big fine car, a nice roll in the bank;

That will please me awhile, til I sat down and think.

Well, the judge said "Minnie - what make you mistreat your man?"

Judge - you know you ain't no woman, and you sure can't understand.

'Cause he holds me, whispers darling, oh what a thrill;

'cause I live the life I love and I love the life I live.

What story do these lyrics tell?

Compare and Contrast

Think about similarities and differences between these examples ...

"One Dime Blues," by Blind Lemon Jefferson

"Hold Me Blues," by Memphis Minnie

- How many instruments / performers?

- What types of instruments?

- Lyrical content?

Learning Checkpoint

- How did the lyrical content of blues songs change as African Americans moved across the United States?

- What are some aspects of blues lyrics that have remained the same, regardless of geography (e.g., rural vs. urban)?

End of Path 1: Where will you go next?

The Blues Stanza

Path 2

20+ minutes

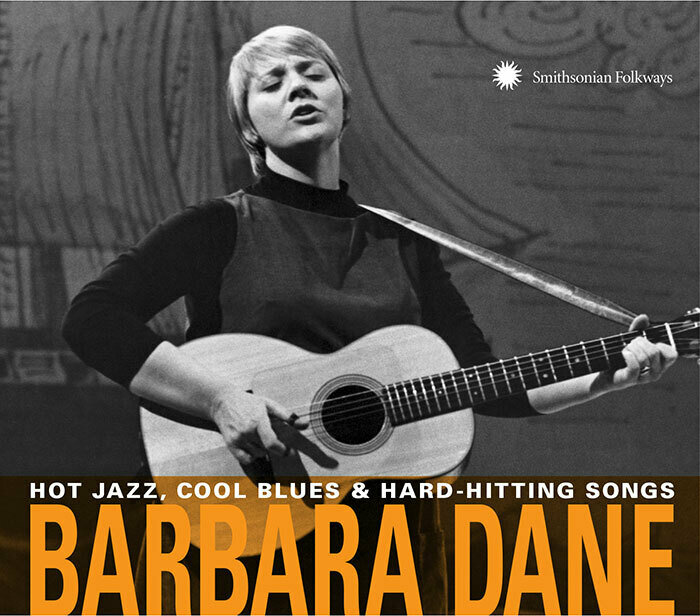

Barbara Dane Performs at the Newport Folk Festival, by Diana Davies. Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives and Collections, Smithsonian Institution.

Opening Discussion

When you're overwhelmed with emotion (good or bad) how do you usually express it?

Expressing Emotion, by Piqsels Medium.

The Blues Stanza

The lyrical structure most associated with the blues uses repetition to help the singer stress the emotion or sentiment of the lyrical content.

This familiar structure is commonly known as the blues stanza.

Blues, by Robert Cottingham. Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Attentive Listening: Discovering the Blues Stanza

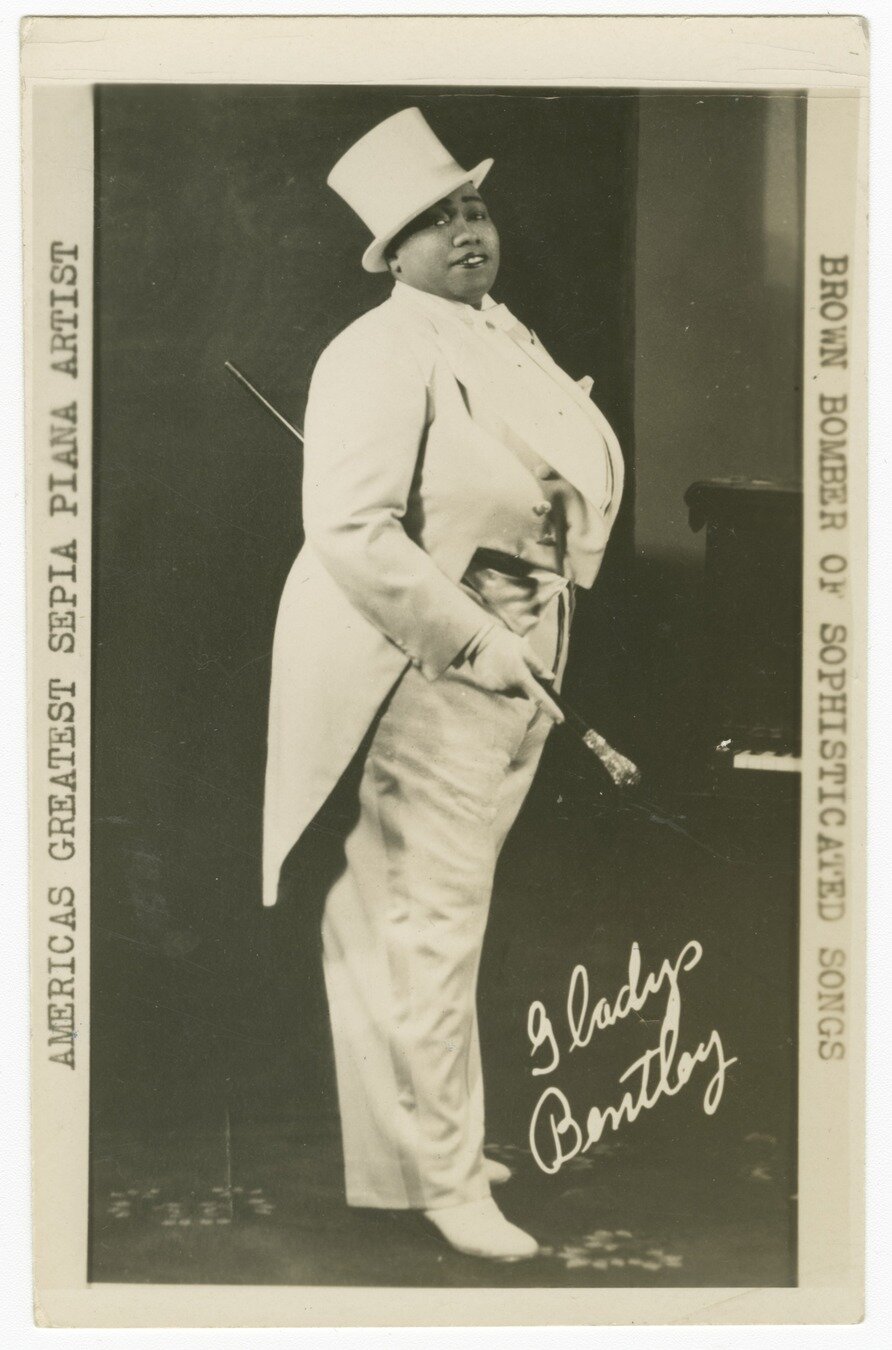

Gladys Bentley:

“Worried Blues”

Listen to the first verse of each example.

What do you notice about the structure of the lyrics?

Memphis Minnie: “Hold Me Blues”

Big Mama Thornton:

“I'm Feelin' Alright”

Barbara Dane:

“Working People's Blues”

Memphis Minnie: "Hold Me Blues"

What story might these lyrics tell?

Memphis Minnie, by Duncan P. Schiedt. National Musuem of American History.

If he holds me in his arms, whisper darling, oh what a thrill;

If he holds me in his arms, whisper darling, oh what a thrill;

'Cause I live the life I love and I love the life I live.

Big Mama Thornton: "I'm Feeling Alright"

What story might these lyrics tell?

Big Mama Thornton, Berkeley Folk Festival, photo by Kelly Hart; © Northwestern University. Courtesy of Berkeley Folk Music Festival Archive, Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections, Northwestern University Libraries.

I'm feeling alright this morning, because my baby's coming home.

Hey, I'm feeling alright this morning, because my baby's coming home.

I got a letter yesterday that he’ll be there this early morn.

Gladys Bentley: "Worried Blues"

What story might these lyrics tell?

What makes you men for treat us women like you do?

Gladys Bentley, unknown artist. National Museum of African American History and Culture.

What makes you men for treat us women like you do?

I don't want no man that I got to give my money to.

Barbara Dane: "Working People's Blues"

What story might these lyrics tell?

Working people get the blues, from morn till late at night.

It's a cold-hearted feeling when there ain't no end in sight.

Working people get the blues, from morn till late at night.

Blues Stanza Basics

Each song you just heard uses a lyrical structure that is very common in blues music. You can think of it as AAB:

I'm feeling alright this morning, because my baby's coming home.

A

A

I got a letter yesterday that he’ll be there this early morn.

B

"I'm Feeling Alright"

The "blues stanza" generally consists of three lines, each of which is set to four measures of music (12 "bars" in total).

Hey - I'm feeling alright this morning, because my baby's coming home.

Listening for the Blues Stanza

Can you identify the blues stanza in each example?

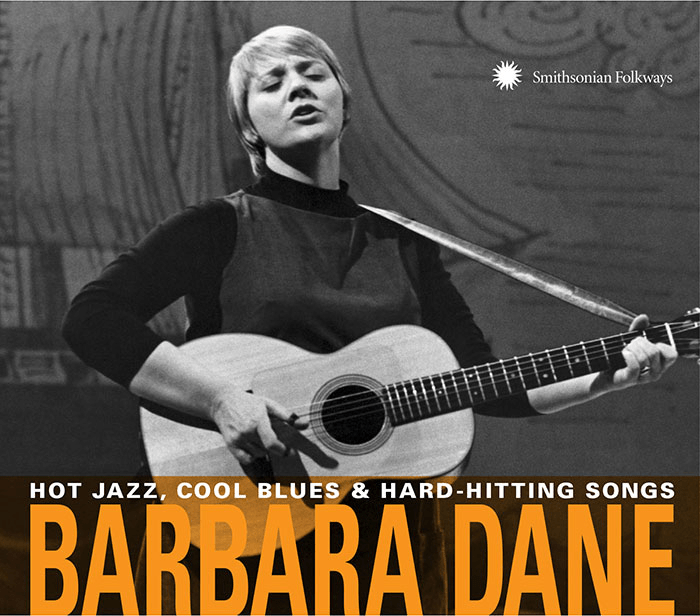

Hot Jazz, Cool Blues & Hard Hitting Songs by Barbara Dane, by Krystyn MacGregor. Smithsonian Folkways Recordings.

"Working People's Blues"

"King Salmon Blues"

"Victim to the Blues"

"Way Behind the Sun"

Meet the Artist: Barbara Dane

Barbara Dane: On My Way [Preview Video], by Smithsonian Folkways Recordings.

Learning Checkpoint

-

What is the structure of the blues stanza?

-

What is the main purpose of the blues stanza (how does it help singers express emotion when they perform the blues)?

End of Path 2: Where will you go next?

Write Your Own Blues Lyrics!

Path 3

30+ minutes

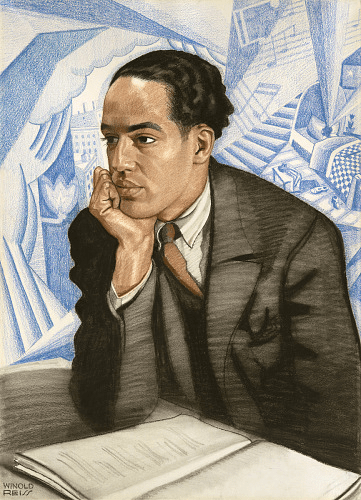

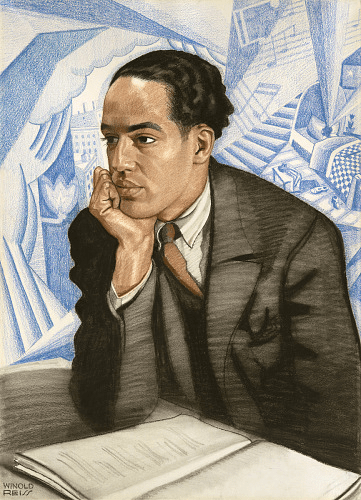

Langston Hughes, by Winold Reiss. National Portrait Gallery.

Generally Speaking .....

Opening Discussion

Why do you think that words have been such an important part of culture for members of Black communities in the United States?

Watch this video...

...which provides insight about the power of words in African American culture.

Giving Voice: The Power of Words in African American Culture, by The Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage, Smithsonian Institution.

The Power of "Words" Through the Blues

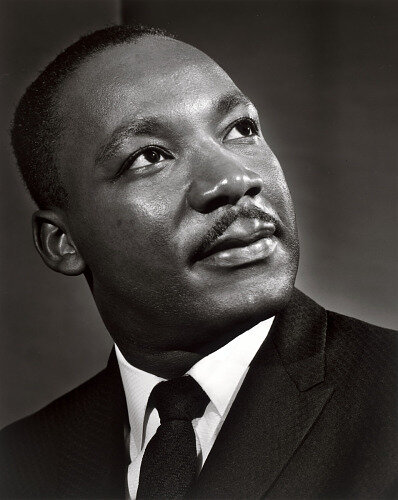

Martin Luther King, Jr, by Yousuf Karsh. National Portrait Gallery.

Blues music has been (and continues to be) a powerful form of cultural expression for Black Americans.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. once said:

The Blues tell the story of life's difficulties, and if you think for a moment, you will realize that they take the hardest realities of life and put them into music, only to come out with some new hope or sense of triumph. This is triumphant music.

Generally Speaking .....

Write Your Own Blues Lyrics!

Blues lyrics represent a powerful use of “words” in Black culture and serve as a powerful form of storytelling.

Blues lyrics are primarily about life—the everyday troubles, wins, and successes of everyday people.

Next, it will be your turn to use your words and experiences to create your own blues lyrics!

The Blues Stanza

The blues stanza is a lyrical structure that is very common in blues music. You can think of it as AAB:

I'm feeling alright this morning, because my baby's coming home.

A

A

I got a letter yesterday that he’ll be there this early morn.

B

"I'm Feeling Alright," by Big Mama Thornton

The "blues stanza" generally consists of three lines, each of which is set to four measures of music (12 "bars" in total).

Hey - I'm feeling alright this morning, because my baby's coming home.

Langston Hughes and the "Blues Stanza"

Hughes deeply admired the blues, and often used the blues stanza to narrate the stories of Black American workers in a familiar Southern dialect.

"Night and Morn" by Langston Hughes

Sun's a settin', this is what I'm gonna sing.

Sun's a settin', this is what I'm gonna sing.

I feel the blues a-comin', wonder what the blues'll bring

B

A

A

Langston Hughes was a writer and poet who used his art and leadership skills during the Harlem Renaissance (1910s–1930s) to speak for those who were excluded.

Considerations as You Create:

What is your main topic? Just like blues musicians, make sure it is relatable and your lyrics are true to your own experiences. (What is going on in your life, family, school, neighborhood, town, state, etc.?)

Keep the blues stanza (AAB) in mind as you compose. Will you use a rhyming scheme?

Practice speaking your text in rhythm. Add expression/emphasis to the second line. Does each line last about four measures (16 beats)?

Done? Write another verse, or perhaps, a chorus. What happens next in your story?

Optional: Add Music

Ideas for adding a musical component to this activity:

-

Add a rhythmic ostinato pattern on percussion instruments as you recite your lyrics.

-

Speak your lyrics in rhythm, using a 12-Bar Blues backing track. There are many tracks available on YouTube . . . here is one example.

-

You could also use Etta Baker's "One Dime Blues" as an instrumental backing track. Find this on Slide 11.3 or on YouTube HERE.

-

-

Create a melody for your lyrics . . . consider using the notes in the blues scale.

-

Sing your melody along with a 12-bar blues backing track.

-

-

Play the chord structure of the 12 Bar Blues (on a chordal instrument such as guitar, ukulele, or piano) as you accompany yourself.

Musical Melting Pot Sketch, by Danielle Nalangan. Smithsonian Folkways Recordings.

Optional: Present Your Work

Present your completed blues lyrics to the class.

Ask your peers if they understand the meaning of your lyrics and their relevance to your life.

-

Were the lyrics about real life experiences?

-

Was your story relatable?

-

Was the blues stanza structure used appropriately and effectively?

-

Would someone listening think that you lived in an urban or rural area?

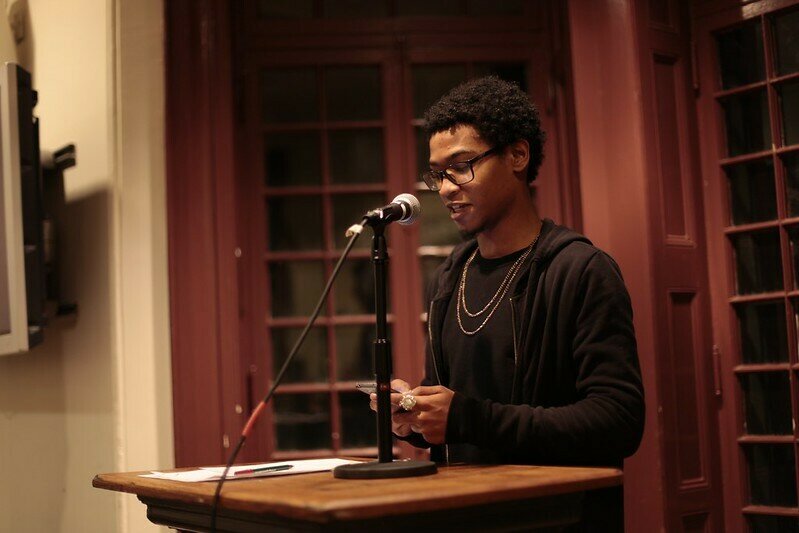

Open Mic Night, by Kellywritershouse, CC BY 2.0, via Flickr.

Learning Checkpoint

- Why have "words" (and blues lyrics specifically) been a important and powerful way to express culture for Black Americans?

- What do you need to consider when writing lyrics for the blues?

End of Path 3 and Lesson Hub 10: Where will you go next?

Lesson 10 Media Credits

Audio courtesy of

Smithsonian Folkways Recordings

Columbia Records

Video courtesy of

Smithsonian Folkways Recordings

Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage

Images courtesy of

Smithsonian Folkways Recordings

The Arhoolie Foundation

Jim Marshall Photography LLC

Library of Congress

Smithsonian American Art Museum

National Museum of American History

National Museum of African American History and Culture

Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage / Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives and Collections

The Etta Baker Project / David Holt

Northwestern University Libraries

National Portrait Gallery

© 2023 Smithsonian Institution. Personal, educational, and non-commercial uses allowed; commercial rights reserved. See Smithsonian terms of use for more information.

This Pathway was funded in part by the Smithsonian Youth Access Grants program and received Federal support from the Smithsonian American Women's History Initiative Pool, administered by the Smithsonian American Women's History Museum. It also received in-kind, collaborative support from the Society for Ethnomusicology and the National Association for Music Education.

For full bibliography and media credits, see Lesson 10 landing page.