Applied

Microeconomics

Lecture 11

BE 300

Plan for Today

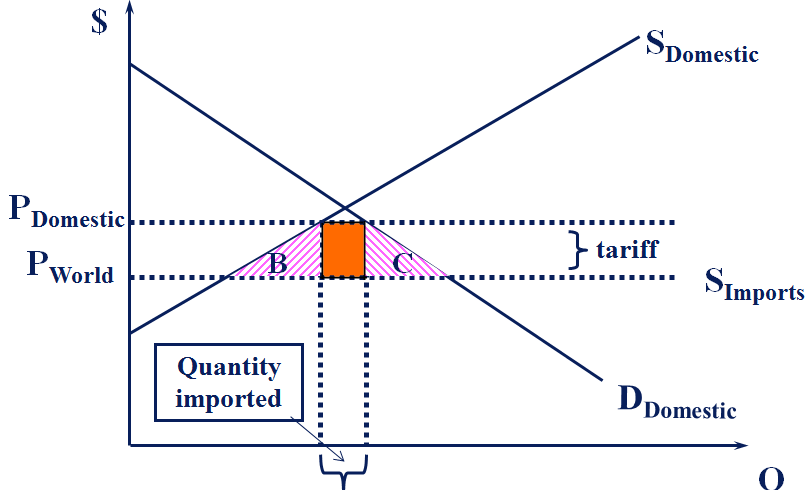

Finish up sugar import quotas

Taxes

Make vs. Buy Decisions: Markets, Contracts, and Vertical Integration

Coming Up

Read and work through Oil case

Ch 14 Intro through Ch 14.4 (will do on Thurs & next Tues)

You should remember calculating present value from finance--if you need a refresher, check out Appendix 7 in textbook.

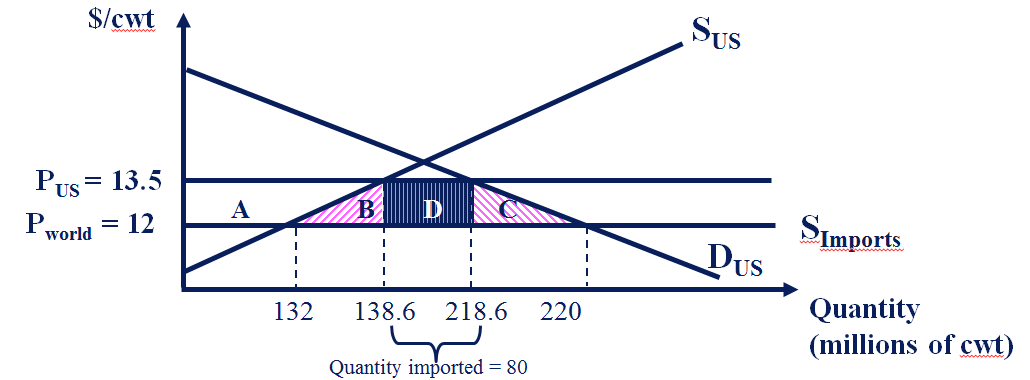

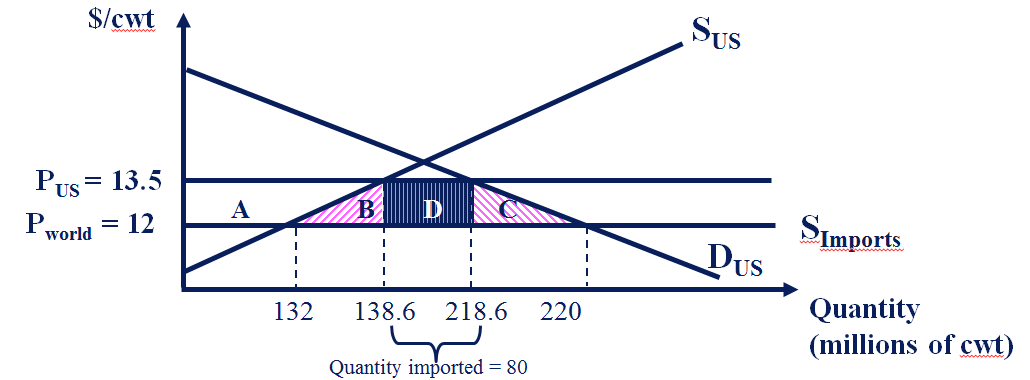

Sugar Case

Loss in CS = A + B + C + D (per year) = $328.95 million

Transfer to U.S. producers = A (per year) = $203 million

Transfer to foreign exporters or U.S. importers = D (per yr) = $120 mil.

If quota, then DWL = B + C (per yr) = $6 mil.

What if we banned imports altogether?

Sugar Case

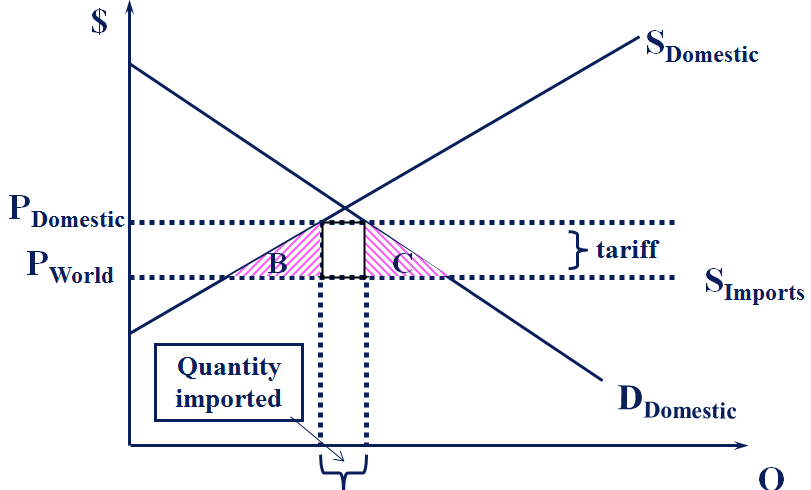

Could we achieve the same result with a tariff?

Sugar Case

How high would the tariff have to be to reduce imports to 80?

Sugar Case

The orange box is the value of quota rights -- either a political gift, auctioned off, or captured through a tariff

Sugar Quotas: Summary

Interference with the competitive equilibrium—price controls, quotas, tariffs—leads to DWL.

Exception: government policies that correctly solve an externality issue (or other market failure).

The surplus transferred from consumers to producers (or vice versa) never counts as DWL—it is just a redistribution of income, not a welfare loss to society.

The lost CS + PS that becomes DWL arises because of the quantity going down below the “free market” (perfectly competitive) equilibrium level.

So--why do we have tariffs and quotas (and why did they persist for hundreds of years)?

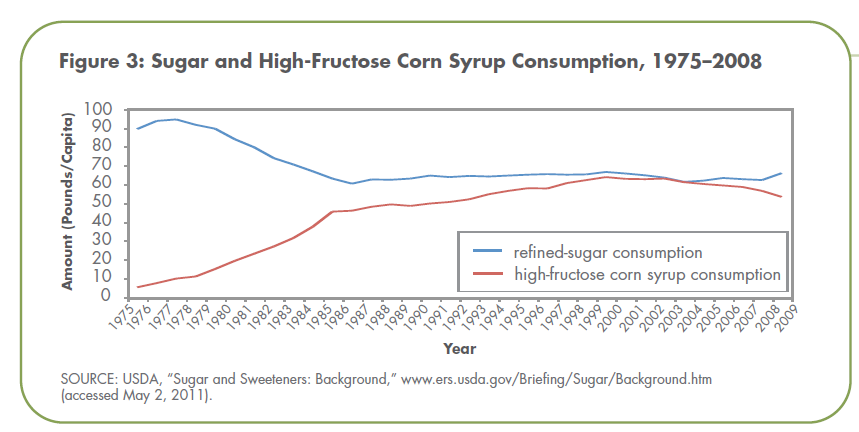

Sugar Quotas: Other Consequences?

Corn producers now also favor a sugar quota

Sugar Quotas: Other Consequences?

•Substitute into high fructose corn syrup and away from sugar

•Now corn producers also favor the sugar quotas

•Many argue that high fructose corn syrup is worse for health than cane or beet sugar

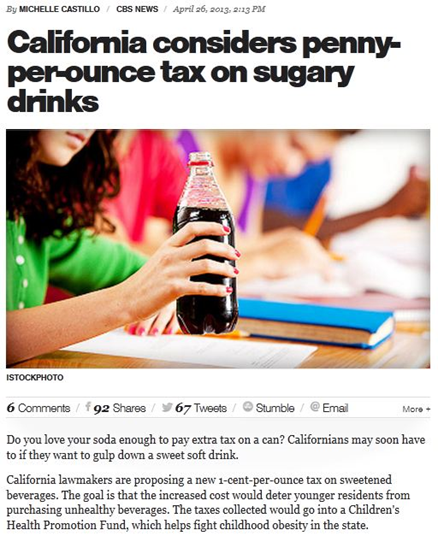

Need another tax to rectify the public health consequences of the sugar quota

Taxes

Taxes are the price we pay for a civilized society -Oliver W. Holmes

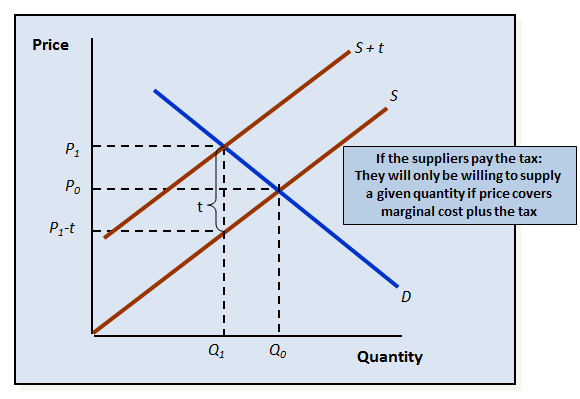

Excise tax: tax per unit of the good

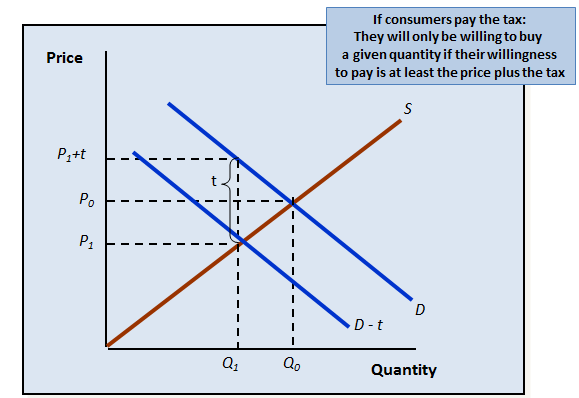

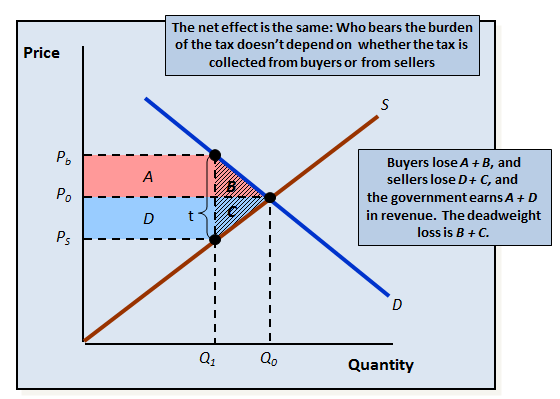

Taxes

Taxes

Taxes

Taxes

Demand and supply for a competitively supplied product are given as follows (where P is in dollars):

a) Calculate the current equilibrium market price and quantity.

b)The government imposes a per-unit tax on suppliers of 20 cents per unit. What are the new equilibrium price paid by consumers, the price obtained by sellers, and quantity? By how much does the price paid by consumers rise? What proportion of the 20 cents do consumers “pay”?

Taxes

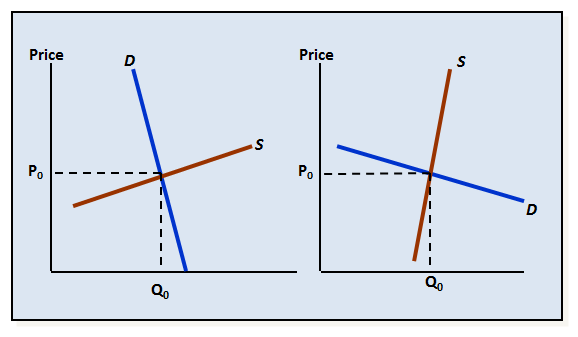

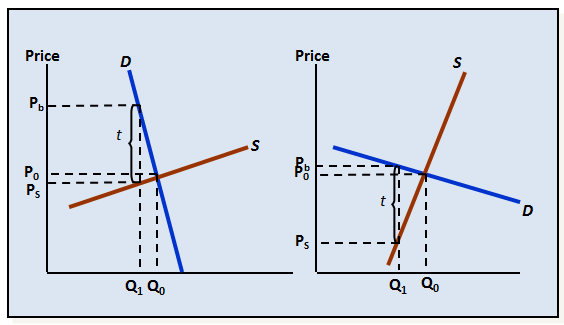

Who pays for the tax depends on the elasticity of demand and supply.

More inelastic (inflexible) -- more of the tax burden falls on you

Taxes

Who pays for the tax depends on the elasticity of demand and supply.

More inelastic (inflexible) -- more of the tax burden falls on you

Taxes

The same basic insight about pass through of taxes applies to anything that raises the marginal cost of production:

- Cost increases: borne by sellers to the extent that demand elasticities exceed supply elasticities.

- Risk

Make vs. Buy: Markets, Contracts, Vertical Integration

The Boundaries of the Organization

American Apparel: Design, cutting, sewing, production planning, photoshoots, shoemaking, advertising, retail... all under one roof.

The Boundaries of the Organization

An old question in economics:

Why do [big] firms exist?

If the market is such a “marvel,” why do we see so many exchanges that could take place in market governed by “central planning” inside firms?

The Boundaries of the Organization

Organization options:

- Market: small firm (purchase inputs and services in the market)

- Contracts: purchase inputs and services in market BUT in context of longer term relationship than pure market transactions

- Hierarchy: Vertically integrate (do it all yourself)

- Global or Local Sourcing: produce inputs abroad or buy from local/foreign operations

“Make vs. Buy”

Companies have to decide which activities to perform themselves and which to “buy” from other firms

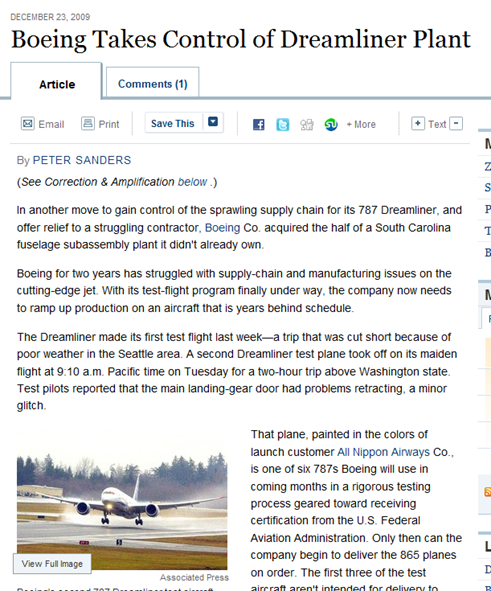

“Make vs. Buy”

Wall Street Journal, December 23, 2009

Boeing had “outsourced” much of the component production of the Dreamliner; ran into delays and found it necessary to take back control of plants.

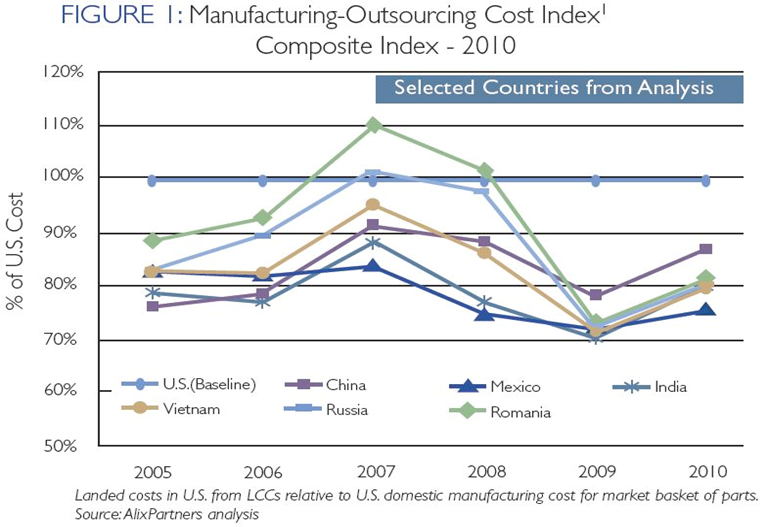

Foreign v Domestic

Companies also need to decide whether to use foreign or domestic sources.

Make vs Buy Overview

Vertical integration

- Make vs Buy

- Transaction Costs

- Hold-up problem

Contracts

Global integration

- Intra-firm trade

- Offshoring and outsourcing

- Multinational firms

Make vs Buy

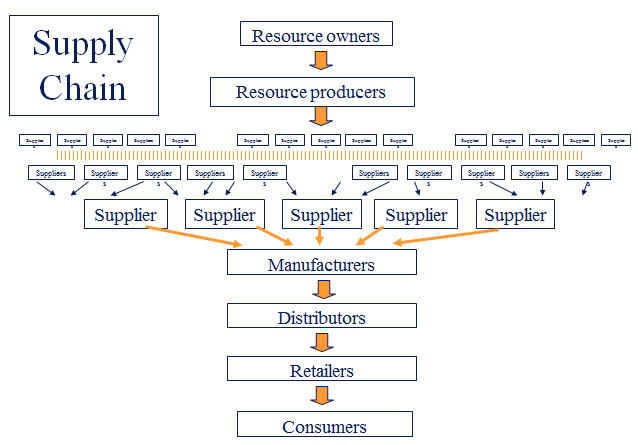

Vertical dimension of the firm: stages of the production process in which the firm participates

To produce and sell a good involves many sequential stages of production, marketing, and distribution activities.

- Integration decision (“make”): what stages will the firm will undertake itself

- Outsourcing (“buy”): transact with another firms for products/services at a production stage

- Global dimension: Outsource from a foreign supplier or build your own factory (offshoring).

Make vs Buy

The Nature of Vertical Integration

A firm that participates in more than one successive stage of the production or distribution of goods or services is vertically integrated.

- A firm may vertically integrate backward and produce its own inputs, or forward and buy its former customer.

- A firm can be partially vertically integrated. It may produce a good but rely on others to market it. Or it may produce some inputs itself and buy others from the market.

- Some firms buy from a small number of suppliers or sell through a small number of distributors. These firms often control the actions of the firms with whom they deal by writing contractual vertical restraints that create quasi-vertical integration (franchisor and franchisee).

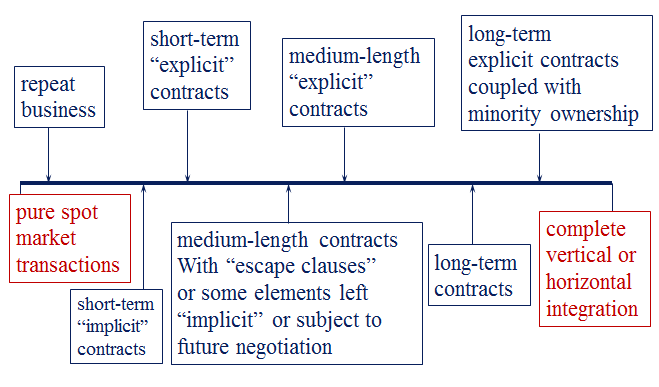

Spot Market to Vertical Integration

Reducing Transaction Costs

Probably the most important reason to integrate is to reduce transaction costs, especially the costs of writing and enforcing contracts.

- A manufacturing firm may decide to vertically integrate forward (downstream) into distribution if the expense from trying to prevent opportunistic behavior by these firms is high.

- Opportunistic behavior is particularly likely when a firm deals with only one other firm: a classic principal-agent problem.

- Coordination costs: integrated firms has greater control over multi-stage production process. Example, American Apparel’s vertically integrated LA plant.

Transaction Costs: Input Reliability

A common reason for vertical integration is to ensure supply of important inputs.

Having inputs available on a timely basis is very important. Costs would skyrocket if a car manufacturer had to stop assembling cars while waiting for a part. Backward (upstream) integration to produce the part itself may help to ensure timely arrival of parts.

Example: River Rouge

Example 1920s Ford: “Henry Ford tried stockpiling parts and materials, but found that the inventory costs were too high. The answer, he decided, was total control: owning the whole supply chain. By the 1920s his company ran coal and iron ore mines, timberlands, rubber plantations, a railroad, freighters, sawmills, blast furnaces, a glassworks, and more. Capping it all was a giant factory at River Rouge, Michigan” – The Economist 3/27/2009

Example 2: Toyota

Alternatively, this problem may be eliminated through quasi-vertical integration contracts (reward prompt delivery, penalize delays), or just-in-time systems.

Example: “Toyota rigorously screens its suppliers for quality and financial health, and then spends time and money to ensure their efficiency and survival, sometimes taking minority stakes. In the 1980s, when Toyota chose Johnson Controls to supply seats, it blocked the supplier from expanding its facility […] Toyota's engineers worked with Johnson to streamline production, rearrange the factory floor, and cut inventories, ultimately showing that expansion wasn't needed after all.” – The Economist 3/27/2009

It is also important to be able to vary production quickly (like during a recession). Vertically integrating may enhance flexibility.

Opportunism/Hold Up

Markets are good at dealing with uncertainty and complexity.

But market exchange tends to break down for transaction that require relationship-specific investments.

Relationship-specific investment ≡ an investment specially designed or located for a specific user that, as a consequence, has a significantly lower value in its next best alternative use (or with the next best user).

Relationship-specific investments increase the risk of opportunism

Opportunism/Hold Up

•Relationship-specific investments expose transactors to the possibility of “hold up”

- The holdup problem arises when two firms want to contract or trade with each other but one firm must move first by making a specific investment (can only be used in its transaction with the 2nd firm).

- Problem: the 2nd firm takes advantage of the 1st firm.

Opportunism/Hold Up

Why do we care?

- Transactors will be reluctant to make relationship-specific investments without some “protection” for their investments.

- 1st firm anticipates opportunistic behavior

- If enforceable contracts are unavailable, the first firm will not invest and both firms lose profits or surplus

Opportunism/Hold Up

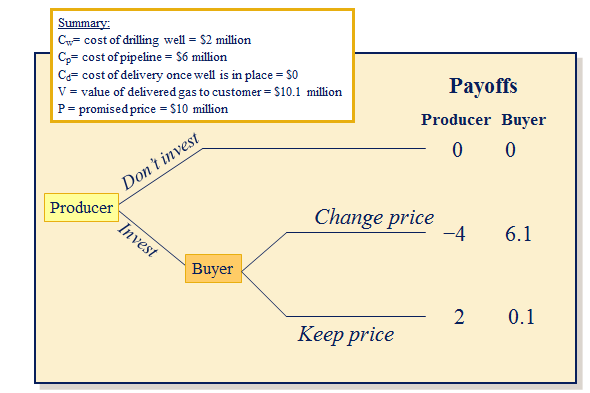

The main method to transport natural gas is via a pipeline.

Assume:

- a natural gas producer finds natural gas in Colorado.

- the cost of developing the well is $2M

- the cost of building a pipeline from the well-head to a buyer's facility is $6M

- the cost of transporting the gas through the pipeline is zero

- the producer could sell this gas to a number of potential buyers/distributors, all of whom value the gas reserve at $10.1 million.

Is it efficient to drill the well and build the pipeline?

Opportunism/Hold Up

Is it efficient to drill the well and build the pipeline?

It is efficient to drill the well and build the pipeline if the value of the gas (to buyers) is at least as great as the cost of producing the gas.

Because the value of the gas is $10.1 million and the cost of extracting it & getting it to market is $8 million (2 mil. + 6 mil.), there are gains from trade of $2.1 million. It is thus efficient to drill the well and build the pipeline.

At what price will they trade?

Opportunism/Hold Up

At what price will they trade?

The producer would only be willing to make the investments if the price is at least $8 million, while the buyers would be willing to pay up to $10.1 million for the gas.

So the price would have to be somewhere between $8 and $10.1 million for the transaction to take place

Opportunism/Hold Up

Suppose the producer and one of the potential buyers agree to split the gains from trade and set the price for gas from the well at $10 million. At $10m, it pays for the producer to go ahead and make its investments.

Hold-Up Problem: Once the pipeline between the well-head and the selected buyer is built, the buyer knows that the producer is “locked” into selling to that buyer.

Opportunism/Hold Up

What is the lowest price that the buyer can offer (and expect the producer to accept) for the gas once the pipeline is built?

The producer could try to sell the gas to another buyer. However, the producer would have to build another pipeline ($6 million).

Even if another buyer offered $10 million for the gas, the producer would “net” only $4 million from the sale ($10m − $6m).

So the producer would be better off selling to the original buyer at any price equal to or greater than $4 million.

Opportunism/Hold Up

So...does it make sense for the producer to develop the well?

If the producer gets “held up” and only gets a price of $4 million, its profit would be

$4 million – $8 million = − $4 million

Opportunism/Hold Up

Opportunism/Hold Up

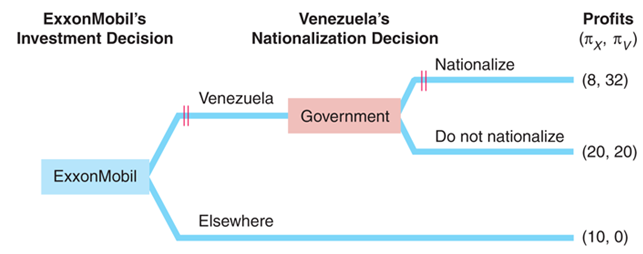

(From p. 450 in textbook):

Exxon to make a costly joint investment to drill for oil in Venezuela, which could nationalize the industry, or in another country. How can you find the solution? Should ExxonMobil invest here?

Opportunism/Hold Up

•Can you write a binding contract that Venezuela would pay ExxonMobil an amount $X if it nationalizes? How large does $X have to be?

•In practice, will a contract solve everything?

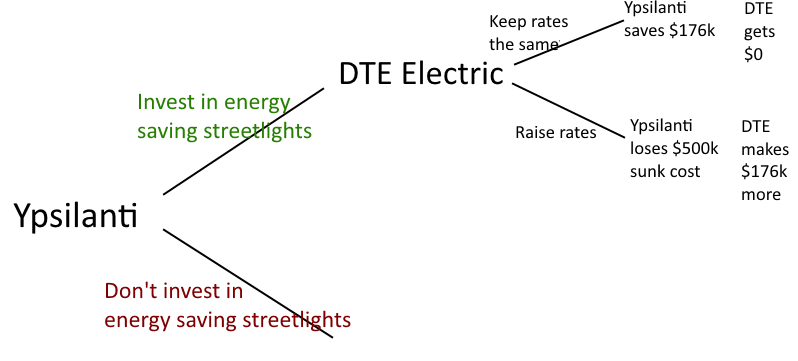

A Local Example...

Hat tip to Semaj Ray for this example!

"We worked with DTE Energy for more than a year on the switch to LED streetlights and at no point in the discussion did they warn us that LED lights would cost more than old high-pressure sodium lights. If this rate hike happens, we'll really feel like this was a bait and switch," said Ypsilanti City Council Member Brian Robb.

GM and Fisher

Fisher Body provided closed metal car bodies under contract to GM

Required Fisher to invest to new plant and equipment

Hold-up problem? Why or why not?

Resulted in contract with protections for Fisher specifying constant markup over Fisher’s variable costs

Fisher could then hold-up GM by threatening to overstaff the plant – why would this matter?

GM ultimately bought Fisher, choosing integration over outsourcing.

Lesson (paradox?): solving one hold-up problem might create another

- You need a lawyer to write contracts

- You need an economist to figure out the incentives!

Other Hold-Up Problems/Solutions

When BMW opened a factory in Greer, SC very few firms were willing to bid to supply specialized parts to the factory (a specialized machine tool cost $100,000)

- Suppliers were worried about hold-up

- So was BMW

- Who has an incentive to behave opportunisitically?

- BMW bought the machines and leased to suppliers

•Large newspapers own their own printing press (Washington Post), while small book publishers typically do not? Why?

Five Strategies (& Examples)

- Contracts: The 2nd-mover firm guarantees the 1st-mover firm that it will not be exploited, GM gave a 10 year exclusive cost-plus contract to Fisher Body.

- Vertical Integration: After years of holdup problems, GM bought Fisher Body.

- Quasi-Vertical Integration: BMW purchased specialized parts equipment and then leased it to South Carolina parts suppliers. Toyota provides training and engineering support to Johnson Controls

- Reputation Building: GM or new government in Venezuela can show its record of not acting opportunistically (establish reputation as straight dealer, “good” company, e.g. Google?)

- Multiple or Open Sourcing: Diversify your supply chain with multiple suppliers of the same part. Helps explain success of open-source software platforms – can always find a new programmer.

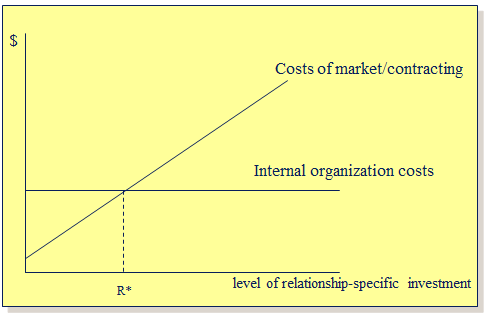

Back to organizing the firm…

When should a firm vertically integrate (“make” v. “buy”)?

•Choose organizational form to minimize transaction costs.

•Costs of market transactions include bargaining costs (including “hold-ups”), contracting costs. Bargaining and hold-up costs rise with the need for relationship-specific investments. Contracting costs rise with the difficulty of contracting (complex products, uncertainty about the future)

•Costs of internal organization include “managerial diseconomies,” bureaucratic inefficiencies. Costs of internal organization rise with firm size.

Implication: Vertically integrate complex products that involve large, relationship-specific investments

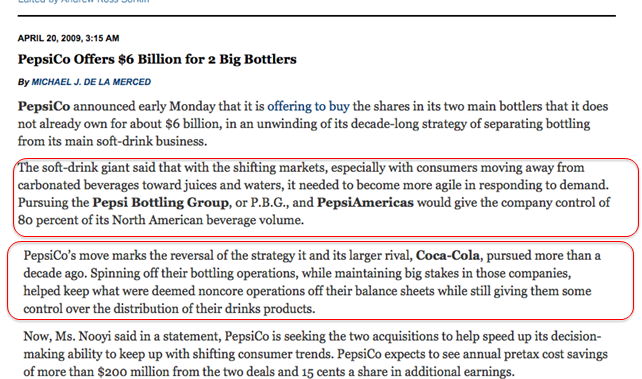

Contracts vs. Vertical Integration

We’ve just looked at one way to reduce the transaction costs or hold-up of using the market: Vertical integration

Another possible form of protection: Contracts

- Make promises credible by make them legally enforceable

- However, being locked into a long-term contract can be hazardous if there is a lot of uncertainty; may get stuck having to buy or sell at a loss

- Benefits of contracts increase with the amount of relationship-specific investments (but so might the costs)

- Costs of contracting rise with amount of uncertainty and complexity

Contracts v. Vertical Integration

Firms wanting to choose the organizational form with the lowest transaction costs would contract for low relationship specific procurements and vertically integrate high RSI ones.

Vertical Integration: Efficiency Reasons

Lower transaction costs w/ VI than with using the market

- Specialized Assets

- Uncertainty (e.g., quality monitoring problems)

- Product is “information” (also a monitoring issue)

- Extensive coordination required (e.g., design interconnectedness)

- Assure access to key input supply

- Internalize an externality (e.g., protect reputation of product)

- Eliminate monopoly power of a supplier or monopsony power of a buyer

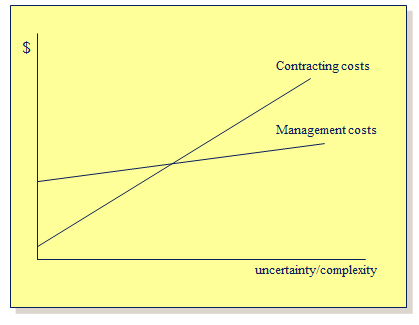

Vertical Integration

How is Complexity/Uncertainty Related?

Uncertainty and complexity raise the costs of both contracting and internal organization, but, on net, uncertainty and complexity tend to increase contracting costs more because of the need to deal with uncertainty in advance (e.g., anticipating all of the things that could go wrong and providing for them in the contract) as opposed to dealing with problems as they arise (“adaptive, sequential adaptation”)

Global Integration of the Firm

Intra-firm trade is makes up over a one third of US imports and exports

- Intra-firm trade: a single firm is on both sides of an international transaction. It exports the output from its operation in one country to an affiliated business unit in another country.

- General Electric (GE), has production facilities in many countries, including Hungary and Romania. To produce a refrigerator, GE must manufacture the basic parts and assemble those parts into a finished product. So, GE may take advantage of intra-firm trade to reduce costs and maximize profits.

Gains from Intra-firm Trade

- Plants and workers can specialize according to skills, costs, productivity or business environment

- Application of opportunity cost and comparative advantage.

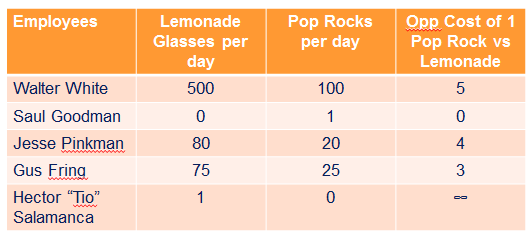

Recall: Opportunity Cost of allocating employees to tasks

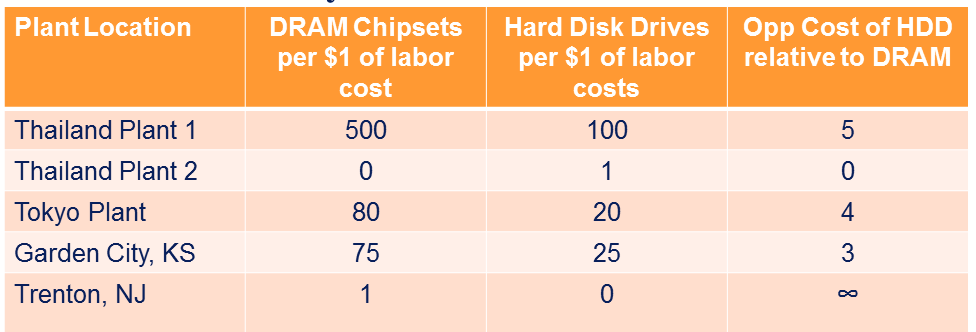

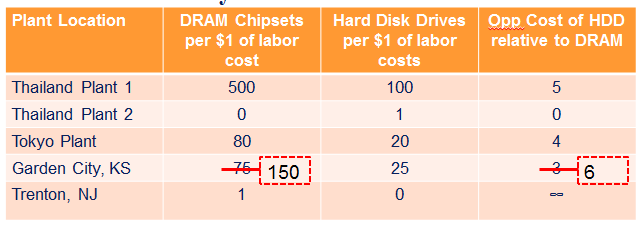

Now Think Globally: DRAM vs Hard Drive Labor Costs

Suppose the price of HDD divided by the price of DRAM = 4.5. Where is HDD production?

Now Think Globally: DRAM vs Hard Drive Labor Costs

•Respond to long-run changes in demand (prices) by moving production across borders to relatively least costly location (medium to long term, harder than reassigning employees)

Now Think Globally: DRAM vs Hard Drive Labor Costs

•Some plants can only do one thing (Thai 2 and Trenton) --- environmental regulations, employee training, wages, space constraints

Now Think Globally: DRAM vs Hard Drive Labor Costs

•If relative price is constant at 4.5, but input costs change (e.g. improved throughput management at Garden City doubles potential DRAM labor productivity). What happens?

Comparative Advantage Can Change