Applied

Microeconomics

Lecture 15

BE 300

Plan for Today

Economics of Information

Adverse Selection

Moral Hazard

For Next Time

15.1 - 15.3 (Today)

Zombie Apps (Write Up Due Next Time)

9.6 and 16.5-16.6 (Thurs & Tues)

Information

Adverse selection:

- one side to the transaction has information that the other side doesn’t – and that information is relevant to the transaction (e.g., to costs).

- Because the side can choose to participate in the contract or not participate, the group that knows they will disproportionately benefit will elect to participate.

Adverse Selection in Auctions

Envelope contains some amount of money between $1 and $10.

Equal probability of any amount.

What is EV?

(1/10)*1+(1/10)*2+...+(1/10)*10=$5.5

Information

Adverse selection in insurance markets refers to the fact that individuals with the highest expected losses will be most inclined to buy a lot of it.

Adverse Selection in Insurance Markets

Assume people differ in their probability of a loss or accident, and the insurer (e.g., vision plan, dental plan) cannot tell ex-ante who is high risk and who is low risk.

For an insurer to at least break even, the insurance premium must be based on average losses, but... who will find insurance more appealing, those with a high probability of a health risk or those with a low probability of a health risk?

Adverse Selection in Insurance Markets

Imagine there are two groups of people: the sick and the healthy.

Sick have a 5% chance of a $100,000 health bill.

The healthy have a 1% chance of a $100,000 health bill.

What is expected value of each groups's health expenses?

If both groups are risk-neutral, how much would they be willing to pay for insurance?

Adverse Selection in Insurance Markets

Imagine there are two groups of people: the sick and the healthy.

Sick have a 5% chance of a $100,000 health bill.

The healthy have a 1% chance of a $100,000 health bill.

Say the insurance company starts out with 50% sick and 50% healthy.

What are their expected costs per person?

In order to break even "on average", what is the minimum premium they can charge?

Adverse Selection in Insurance Markets

Imagine there are two groups of people: the sick and the healthy.

Sick have a 5% chance of a $100,000 health bill.

The healthy have a 1% chance of a $100,000 health bill.

If they charge a premium of $3000, how many sick people sign up and how many healthy people sign up?

Adverse Selection in Insurance Markets

Taking it one step further... suppose WITHIN the group of sick people, half are "very sick" and half are "slightly sick."

The very sick have an 8% chance of a $100,000 health bill.

The slightly sick have a 2% chance of a $100,000 health bill.

Currently the premium is at $3000 (the average among the sick).

Who among the sick is interested in buying health insurance?

Adverse Selection in Insurance Markets

Now assume within the "very sick" there are two groups: the "extremely super sick" and the merely "very sick".... etc.

As premium rises, the relatively healthy want to leave. This makes the premium rise more and the pool of the existing insured get more expensive. Which in turn causes more relatively healthy people to leave...

Eventually, only the most sick remain in the insurance pool, and premiums are very very high.

Health economists call this a "Death Spiral" (dun dun dun!)

Adverse Selection in Insurance Markets

If the Supreme Court strikes the Obama health care reform law’s requirement that all individuals buy health insurance or pay a penalty, but leaves intact popular provisions that forbid insurers from denying coverage to people who are sick or charging old people more than three times the premiums paid by the young, would the health care system collapse under the weight of too many patients and too little money?

Without Mandate, an Insurance ‘Death Spiral’? Business Week March 2012

Adverse Selection in Insurance Markets

What are some solutions to adverse selection in insurance markets?

If insurance companies can figure out individual's expected health risk, they can charge their expected costs--the healthy pay less so they stay in the plan. But who gets hurt by this?

Maybe you can pool people with similar risks together, for example through an employer, and encourage them all to sign up. But some people will still be left out...

Require everyone purchase insurance--the healthy cannot "opt out." But who loses out with this option?

Adverse Selection in Insurance Markets

There are fears that the ability to "adversely select" in insurance markets might only get worse as genetic testing becomes available:

Although insurers have until now kept adverse selection at bay, the issue is likely to become more difficult with the advent of genetic testing, which will greatly expand the amount of knowledge available on individuals’ mortality risk…If insurers are not allowed to demand the results… the asymmetry of information will become more pronounced and adverse selection will become highly significant…

From When Ignorance Is the Best Policy, Financial Times

Adverse Selection in Insurance Markets

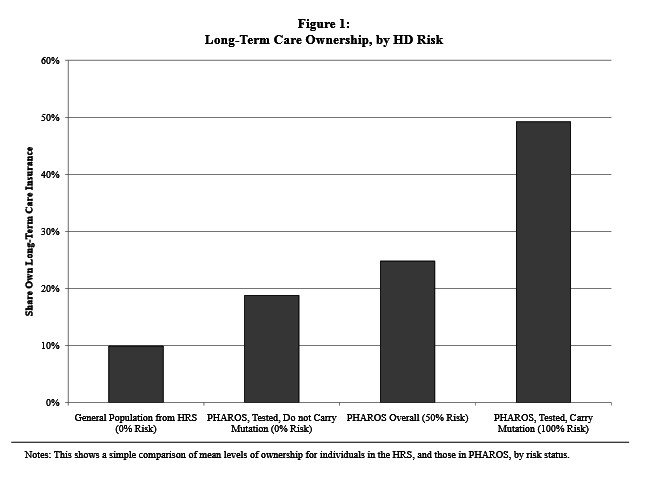

From Oster, Shoulson, Quaid and Dorsey Journal of Public Economics 2010

Adverse Selection

Adverse Selection is not a problem confined to insurance markets. For example:

- You purchase a new car, drive it for 1 month, and then get transferred to London. You decide to sell your car.

- Will you be able to sell the car for the price you paid minus one month of depreciation? Why or why not?

Adverse Selection

If the party without the information (e.g., used car purchaser) cannot distinguish high-quality/low-risk goods from inferior (low-quality/high-risk) goods, it will have to offer a price based on the average quality.

This creates a market failure

- only parties with low-quality goods (high risks) will find a price based on average quality attractive;

- parties with high quality goods (or low risk) will not participate in the market

Result: the average quality of goods in the market falls, causing the uninformed party to adjust its price lower, causing more high-quality sellers to leave the market.

Adverse Selection

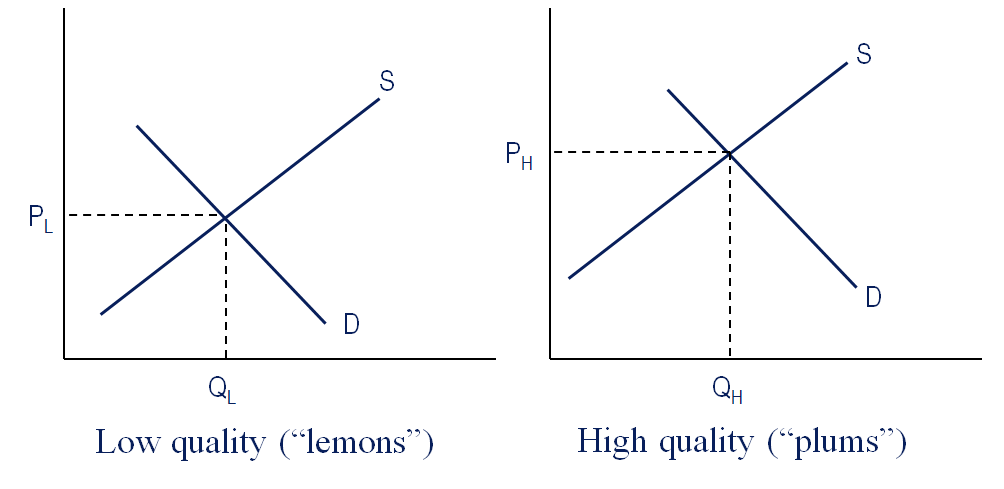

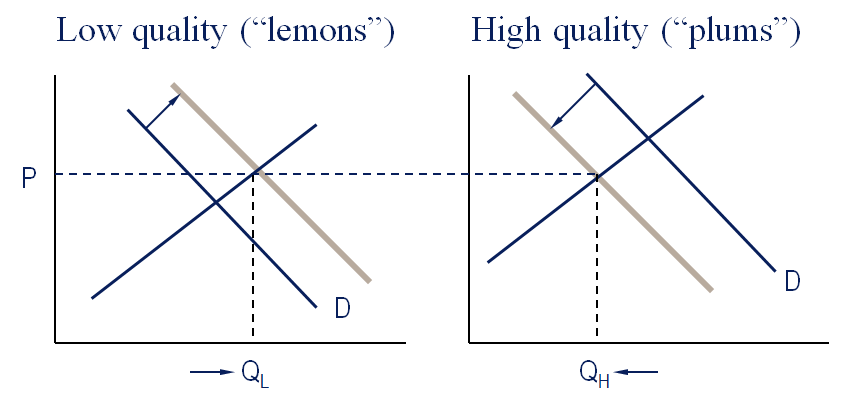

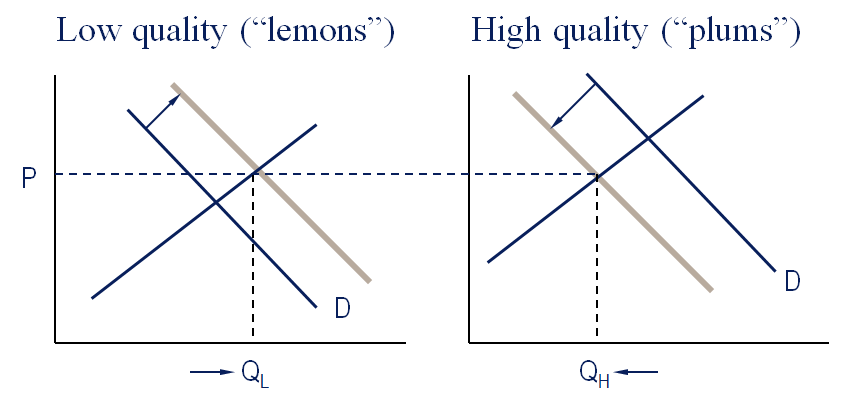

Assume there are two types of cars: high quality ("plums") and low quality ("lemons"). If you can tell the two apart, "plums" will sell for more than "lemons" -- there will be two different prices.

Information

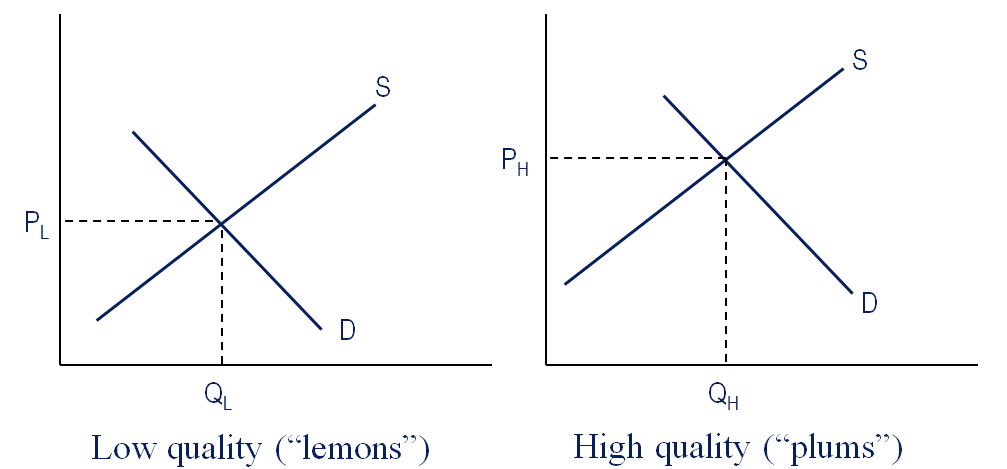

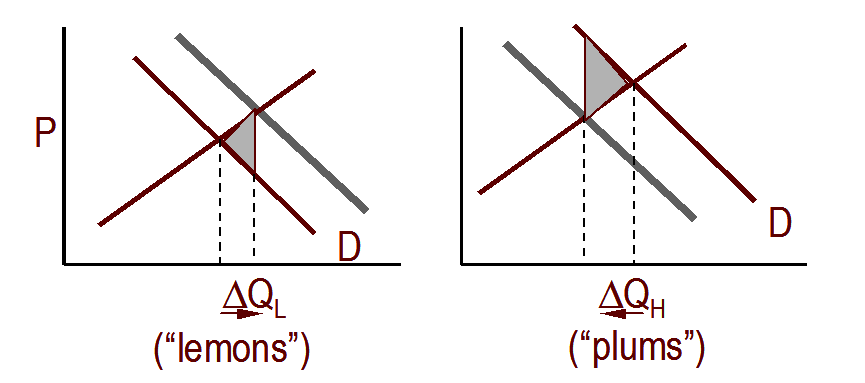

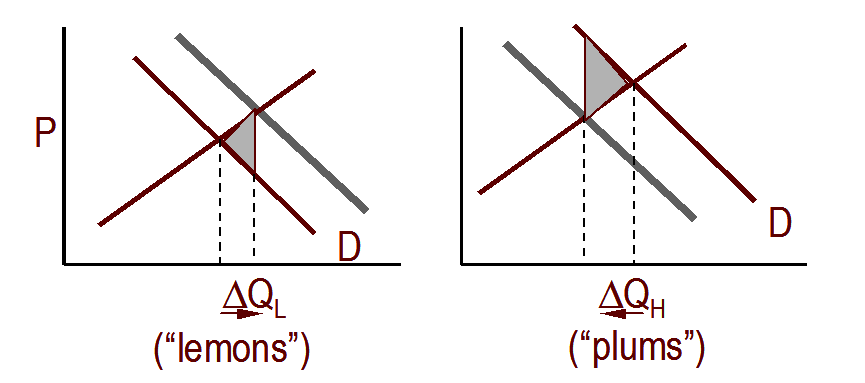

Now imagine buyers can't tell the two types apart, and they know that there's a possibility they will get a lemon instead of a plum or a plum instead of a lemon. What will happen to the demand curves?

Information

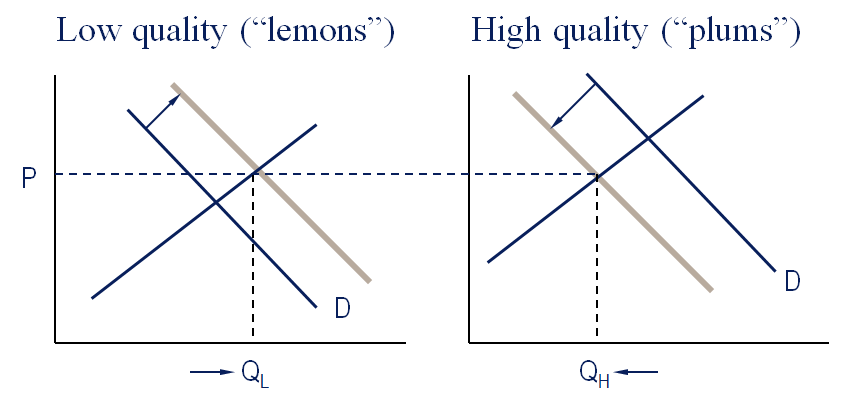

If they truly can't distinguish between types, the market will drive the price to be the same in both markets. This will increase the QL and decrease QH

Information

What does average quality (i.e., ratio of "plums" to "lemons" in the market) look like in this market relative to a market where there's complete information?

Information

Average quality is worse than it would be with complete information: "the bad drives out the good"

Information

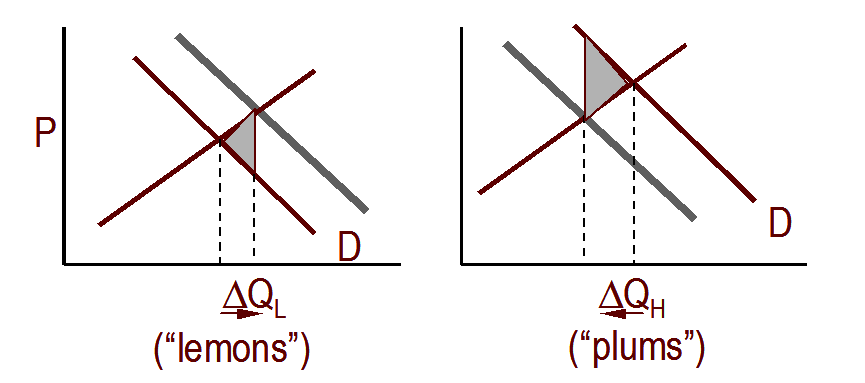

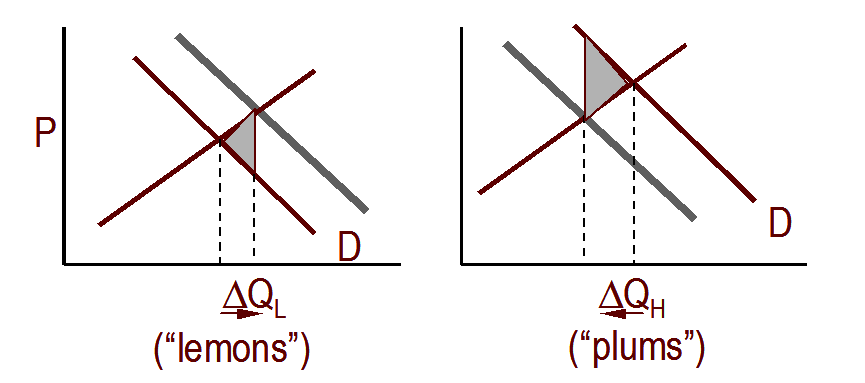

•If buyers cannot tell quality, there are too many sales of lemons compared to the optimum and too few sales of plums.

Information

•If buyers cannot tell quality, there are too many sales of lemons compared to the optimum and too few sales of plums. This creates DWL.

Information

•The DWL is driven by not realizing all of the gains from trade (plums) and going too far into the region of losses from trade (lemons)

Information

Who is made better off by the lack of information? Who is made worse off?

The End Result: A Market for Lemons

Asymmetric information means that quality is worse than it would be with complete information

- “the bad drives out the good”

There is DWL

- sellers of low quality used cars are better off

- sellers of high quality used cars are worse off

- some buyers are better off (which?), some are worse off (which?)

In some extreme cases, plums may be driven out of the market altogether, with the equilibrium price dropping to PL

A Market for Lemons

Back to selling & buying a used car…

Ways to address this issue and minimize the problem?

- Buy from a friend

- Take car to mechanic

- Buy from dealer with warrant

Still, the price differential shows the incomplete effects of these schemes to verify quality.

Even with one of these risk-reducing options, our seller moving to London will not be able to sell the new car for the price paid minus one month of depreciation

Asymmetric Information

Two ways to equalize information:

Screening: Uninformed party takes action to gather information

Examples: physicals (for life insurance); inspection by mechanics for used cars

Signaling: Informed party takes action to provide information.

Signalling

Establish Reputation: communicate information about past product quality via established brand name, being highly rated compared to competition.

Guarantees or Warranties: Profitable for a firm only if quality is high and number of warranty claims is low.

For signals to work, they should have a lower cost for the seller of high quality good than for the seller of a low quality good.

Signalling

For example: guarantees or warranties

If you are selling a high quality good, is offering a guarantee or a warranty expensive to you or inexpensive?

What if you are selling a low quality good?

Costs are different depending on the "unobserved" quality, so low-quality sellers will not offer--it is too costly for them!

Signalling

Suppose buyers of antiques cannot immediately distinguish between genuine items and fakes. A seller of genuine antiques is considering three possible strategies to signal quality:

a) Post a sign outside the store that says “All Items Genuine”

b) Guarantee to buy back anything that it sells at the original sale price at any time

c) Spend thousands of dollars to develop a brand that assures buyers that it deals only in genuine articles

Are these signals equally effective? Will sellers of fakes adopt the same strategies? Why or why not?

An Aside About Signalling and the Labor Market

Employers face asymmetric information when they are hiring a new employee. One piece of information they use is education (GPA, degree, major, etc).

An Aside About Signalling and the Labor Market

Two views of education in economics:

a) Education makes you more productive. You are a better employee because of your education (more knowledge, broader skillset, etc).

b) Education doesn't make you more productive, but it is a signal of your productivity. If you are lazy, disorganized, not hard-working, etc, you will find it very costly/difficult to get a degree. If you are productive, hardworking, reliable, etc, you will find it less costly to get a degree.

There's evidence for both phenomena at work (inherently more productive do tend to get more education, but education also makes you a better employee by teaching you necessary skills).

Screening

Screening: uninformed party’s effort to learn the information that the more informed party has.

- Successful screens should be unprofitable for “baddies” – too costly to mimic “goodies” behavior.

- Every successful screen can be used as a signal

Moral Hazard

There might not just be unobserved information about the cost or the quality of a good or service. There could also be unobserved information about the action that a certain person is taking.

Moral Hazard occurs when one person is more likely to take on risks or incur costs because someone else is bearing the burden of those actions.

Moral Hazard

Moral hazard in insurance markets refers to the tendency for individuals to take less care to reduce risk if they are insured. This leads to larger insurance claims and higher premiums.

The insurance company would like to right in the contract that the individual should not take excessive risks--but the day-to-day activities of an individual are difficult or impossible for the company to observe.

Moral Hazard

Moral Hazard may lead an individual to:

- Take less care to reduce the probability of bad outcomes.

- Take less care to reduce damages when bad outcomes occur.

Moral Hazard

"Face it, girls. I'm older and I have more insurance."

Moral Hazard

Individuals may use more services once insured (medication, tests, etc.)

- companies must charge higher insurance premium

Car owners may spend less on maintenance if they have a warranty.

- increases cost to manufacturers of providing warranties

How would you deal with this if you were an insurance company or had offered a warranty?

Moral Hazard

Common in insurance but not specific to risk and insurance

General version: when you contract with people whose actions you cannot “perfectly” observe (or evaluate or “monitor”), they may take advantage of you.

Moral Hazard

There is a lot of debate on this subject – about what kind of car handles best. Some say a front-engined car; some say a rear-engined car. I say a rented car. Nothing handles better than a rented car. You can go faster, turn corners sharper, and put the transmission into reverse while going forward at a higher rate of speed in a rented car than in any other kind.

P.J. O'Rourke

Moral Hazard & Principal-Agent Problems

Principal: “owner” or uninformed/lesser informed party who contracts with a second party to perform a service

Agent: “employee” or informed/better informed party who contracts with the principal to perform a service

Opportunistic Behavior: agents acting in their own best interests, counter to the interests of the principals who hired/retained the agents

Principal-Agent Problems

Examples of Principal-Agent Relationships?

- Stockholders (principals) & CEO/Management (agents)

- Managers (principals) & employees (agents)

- Homeowner (principal) & contractor (agent)

Principal-Agent Problems

Ways to Deal with Principal-Agent Problems

So, if you are the "principal" hiring an "agent," what are some ways to deal with this problem?

Ways to Deal with Principal-Agent Problems

Monitor your “agent”

- Fixed payment or salary

- Supervise your workers, contractor, etc.

=> shirking, adverse selection, monitoring costs

“Sharing” contract with some monitoring

=> some shirking and some risk compensation

E.g., Deductibles: you have to pay a portion of your car repair bill, hospital bill, etc.

Ways to Deal with Principal-Agent Problems

Use “incentive” pay

- Pay based on performance rather than a fixed wage (e.g., cab drivers)

- In “commission” jobs, need to compensate employee for additional risk of income uncertainty

Always a challenge to provide the right incentives (align incentives)

Aligning Incentives

There are other ways to give incentives :

- Reputation effects (e.g., market for managers)

- Dismissals (for employees, lawyers, advertising agencies) or takeovers (for managers)

- Tournaments (promotions within firms)

- Efficiency wages (Ford’s idea from the early 1900’s; Starbucks) or other “efficiency benefits”

But Be Careful...

•Performance-based compensation can backfire

•The principal must define performance appropriately and objectively, and be able to measure it

•You must be careful about hidden incentives in compensation schemes. Examples:

Safelite Windshield—Piece rates & quality

Ratchet effect: If goals go up as performance increases, employees will resist increasing effort

•Performance-based compensation is necessarily more risky to the employee

- We saw in the “Failures in Franchising”case, if the employee is risk averse, it costs more to the firm to have employees bear risk