Applied

Microeconomics

Lecture 16

BE 300

Plan for Today

Zombie Apps

Economics of Intellectual Property

Coming Up

Ch 16.4-16.6

Ch 9.6

(Continued through Tues)

Information and the Internet

The internet has solved information problems in many markets:

- Extensive reviews of restaurants, products

- Easy to compare prices on different websites

But in other ways, it has created new problems:

- Often must buy products "sight unseen" when online shopping.

- So many products available that it is costly to figure out which is the best.

Information and the Internet

"This is what I get for ordering my wedding dress on eBay..."

Information and the Internet

This case deals with a market where the quality of the product is often difficult to ascertain before purchase: iPhone apps.

There are thousands of available apps out there--some very inexpensive and many with no reviews of other information that can help guide you as to the quality. Many of these apps have not been downloaded even a single time (have been dubbed "Zombie Apps").

Information and the Internet

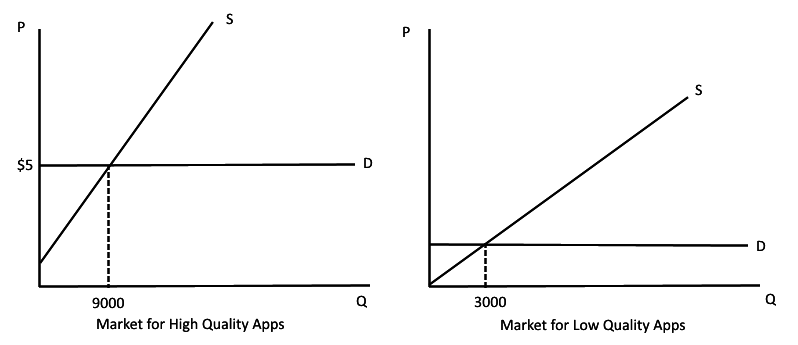

For simplicity, assume there are two types of apps: "Low quality" and "High quality." Risk neutral consumers are willing to pay $0.30 for a low quality app and $5 for a high quality app, and demand is perfectly elastic at those prices.

The supply of low-quality apps is given by

and the supply of high-quality apps is

Information and the Internet

If consumers are easily able to discern which apps are high vs. low quality, what will be the price and quantity of high quality apps? Of low quality apps?

How could we graph that market using supply and demand curves?

Information and the Internet

Zombie Apps

Now assume it is difficult to ascertain the quality of an app before purchase. Consumers believe there is a 50% chance that the app is low quality and a 50% chance that the app is high quality. How much are they willing to pay for an app now? Remember: They are Risk Neutral

E(value of app) = 0.5 x 5 + 0.5 x 0.3 =$2.65

At this price, how many high-quality apps will be supplied? How many low-quality apps? Were consumers correct about the relative probabilities of high and low quality apps?

Zombie Apps

High quality apps:

Low quality apps:

So what fraction of apps are actually high quality? Only (4.3)/(4.3+26.5) = 14 percent (rounding) -- consumers were too optimistic about app quality!

Zombie Apps

How does the current fraction of high quality apps compare to the market with full information? Higher or lower?

Current fraction of apps that are "high quality": 14%

With full information: 75%

"The bad drives out the good"

High quality app suppliers cannot fully benefit from being high quality (that is, they cannot get the full $5 for their product), so they produce less.

At the same time, the low quality apps benefit from being grouped together with the high quality apps -- they produce more.

Zombie Apps

Now let's assume consumers update their beliefs to reflect the correct ratio of high quality to low quality apps in the market. What happens?

Willing to pay even a lower price--further driving out the good apps. Now they are willing to pay only 0.14 x 5 + 0.86 x 0.3=$0.96 (rounding).

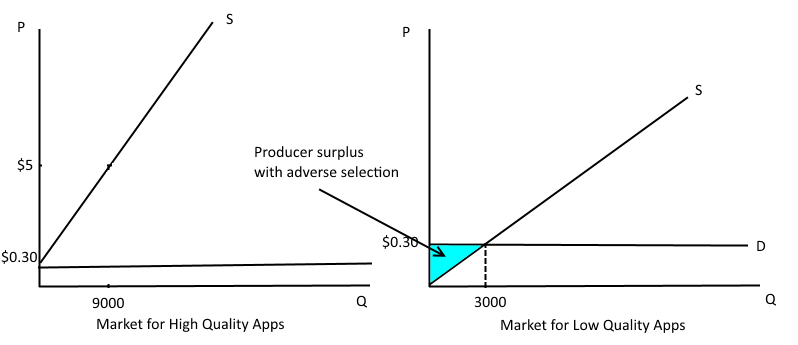

However, as the price falls, even fewer good apps will be available--causing the % of good apps to fall more--and then causing the price to fall even further. Eventually there will only be "low quality" apps and the price will be $0.30.

Zombie Apps

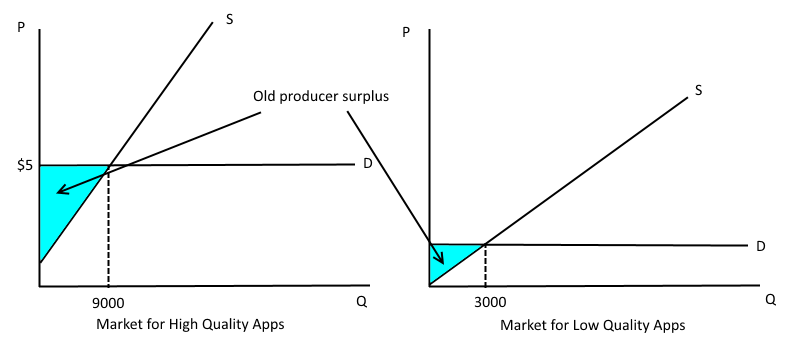

What has happened to producer surplus?

Zombie Apps

Producer surplus with full information

Zombie Apps

Producer surplus with asymmetric information

Zombie Apps

Now let's say there was a way to reveal quality, but at a cost--you could offer a "freemium" version of the app.

- This would lower your customer's willingness to pay for the app by $0.30 (because now they can get a free, although inferior, version).

- But, it would reveal the quality of the app to your customers--they could determine for sure whether it was high or low quality.

- Assume customers will always check out the freemium version--that it is costless in terms of time and money spent (this is probably not true!)

Zombie Apps

Costs of the low quality app producers:

Costs of the high quality app producers:

Current price of an app is $1.

If high quality app producers offer a "freemium" version, what would be their profit? How about if a low quality app producer did the same?

Zombie Apps

If high quality apps offer a freemium version, they can sell their product for $4.70.

They will sell where MC=MR. MR here is price, because demand is perfectly elastic. MC is 0.50 + 0.50 Q. So they will sell Q=8.4, and TR is 8.4 x 4.7 =39.48. TC is 0.50 x 8.4 + 0.25 * 8.4^2 = 21.84.

So profit will be 39.48 - 21.84=17.64, or $17,640.

What about the low quality guys?

Zombie Apps

If low quality app company offer a freemium version, they can sell their product for $0 because it will be revealed to be low quality.

Clearly they would rather not offer a freemium version and try to sell at the current market price of $1.

Zombie Apps

So... if you see an app with a freemium version, what do you know about its quality, even if you don't bother to download the freemium version?

The freemium app is a signal--it only makes sense for high quality app producers to adopt it. All high quality app producers will adopt a freemium version, but no low quality app producers will. Given this information, what do you suspect will happen to the price of apps without a freemium version?

Zombie Apps

Eventually, consumers will learn that all apps without a freemium version will be low quality, so those apps will sell for only $0.30. All apps with a freemium version will be high quality, and those apps will sell for $4.70.

Innovation and IP

Innovation is the creation of information.

And…information is nonrival in consumption.

Translation: marginal cost of providing information to an additional consumer/firm/entity is ZERO

Why? Once the discovery is made, people can “consume” it at 0 cost

(ex-post) efficient allocation is at p=MC=0.

This price corresponds to the maximum utilization of info

Innovation and IP

•What if p*=0?

•Firms would not invest in inventions without expectations of rewards (e.g., profits)

~It’s expensive to invest in R&D in order to find new products and processes. Risks of appropriation by competitors decrease firms’ incentive to invent

•Policy challenge: creating the optimal institutional framework to get innovation incentives right

Questions

•If there were no patents or other gov’t incentives, would there be too little R&D?

•If there is too little R&D, should the patent system be used or should we rely more on other incentives such as prizes, research contracts, and joint ventures?

•Given that the patent system is here to stay, how long should patent protection last to obtain the best possible tradeoff between incentives to invest and the harms from monopoly?

- How does the product market structure affect the incentives to conduct research and the timing of innovation?

How to Incentivize Innovation

Patents (introduced in Venice in 1474)

- give the inventor property rights to the invention for a fixed period of time

- encourage inventors to disclose inventions to (potential) competitors

What are Patents?

•Exclusive right to one’s invention (product, process, substance, or design)

•Useful, novel, and nonobvious

•Must publicly describe/disclose the innovation

•Types of patents: utility patents, design patents, and plant patents

•Patent lasts for 20 years in the United States and most other countries. The 20-year life begins when the patent application is made. (Exception for design patents – 14-year patent life.)

What are Patents?

•44% of patent applications granted in United States (compared to 25% in France, 16% in Germany, 14% in United Kingdom, 12% in Canada, 11% in China)*

•The holder of a patent may either make sole use of the discovery or license others to use the invention at a mutually agreed-on royalty rate

•Probabilistic device with a high degree of uncertainty about whether they will be enforced

•Patents can be invalidated by the courts during an infringement hearing

* Dennis Carlton & Jeffrey Perloff, Modern Industrial Organization 528 (2005).

Patents as a Policy Trade-Off

Tradeoff between static & dynamic efficiency:

- Patents allow for appropriation of benefits of invention at the expense of greater use of information

- A long patent life favors the developers of information at the expense of information users

- A short patent life favors users of information at the expense of its developers

During the life of the patent, price of information is positive. Since p>MC=0, then the resulting price is too high from a welfare standpoint & info is underutilized

Other Policies to Incentivize Innovation

Copyrights

- Exclusive production, publication or sales rights to artistic, dramatic, literary, or musical works

- Cover artistic expression, not ideas, devices, mechanisms

- Copyrights to businesses last 95 yrs; copyrights to individuals last for life + 70 yrs

Other Policies to Incentivize Innovation

Trademarks (e.g., Bib the Michelin Man)

- Do not expire, but . . .

- A firm may lose trademark protection if word comes to signify all products in category (e.g., aspirin, cornflakes, escalator, nylon, yo-yo)

Trade Secrets

Other Policies to Incentivize Innovation

Prizes*

- Ex ante, e.g., the longitude prize (1714, British Gov’t)

- Ex post, e.g., Daguerreotype photography (1839, French Gov’t)

- Extensive use historically of prizes (France, England, Japan)

- Current Examples: X-prize Foundation, NASA Centennial Challenge

Prizes may have some advantages over patents

- Government buyout: efficient level of innovation, no DWL

- Compensation based on auction (= private value of invention)

Drawback is informational constraints on determining value

- Inventors can potentially distort market signals about value

* Tom Nicholas, What Drives Innovation?, 77 Antitrust Law Journal (2011).

Other Policies to Incentivize Innovation

Government-Financed R&D

- Tax incentives: 20% tax credits (activity classified as “R&D” expanding over time)

- Research contracts

When allocated through competitive bidding, possibility of moral hazard (i.e., effort)

- Crowding out of private R&D financing?

- Bias in R&D when jointly financed by gov’t & private sector?

Do Patents Actually Encourage Innovation?

Some argue that the current patent system actually discourages rather than encourages innovation. Why?

Companies take out patents on products they have no plan on producing simply to sue other companies (patent trolls). This increases the cost of producing to other companies.

Artists (or the families of long-dead artists) may sue for copyright infringement if music or art is inspired by previous works.

Do Patents Actually Encourage Innovation?

Example: Smartflash wins $533 million on patent infringement from Apple for patent on data storage system

Do Patents Actually Encourage Innovation?

Apple: Smartflash makes no products, has no employees, creates no jobs, has no US presence, and is exploiting our patent system to seek royalties for technology Apple invented. We refused to pay off this company for the ideas our employees spent years innovating and unfortunately we have been left with no choice but to take this fight up through the court system. We rely on the patent system to protect real innovation and this case is one more example of why we feel so strongly Congress should enact meaningful patent reform.

"Company with no product wins $533M verdict vs. Apple, says it’s no “patent troll”," Ars Technica

Do Patents Actually Encourage Innovation?

Smartflash: The thing about a patent is—let's say you have a university professor who spent two years researching something. It's irrelevant the effort that [an infringing company] spent to build it. It's the person who came up with it first. That's the way the Constitution, and the patent laws, are written. It's designed to cause people to spend money and time innovating. The patent office publishes it, so that advances the state of the art. In exchange for that, you get a property right.

"Company with no product wins $533M verdict vs. Apple, says it’s no “patent troll”," Ars Technica

Do Patents Actually Encourage Innovation?

"Blurred Lines" Robin Thicke and Pharrell -- too similar to Marvin Gaye's Got to Give It Up? Jury recently awarded $7.4 million

to Marvin Gaye's family

Do Patents Actually Encourage Innovation?

For young songwriters to come along and get their songs scrutinized will kill the business of songwriting because it doesn’t give anyone the incentive to want to write songs. How can there be new stars when the old ones use their publishing rights to squelch those underneath them?

Room for Debate, NYT

Do Patents Actually Encourage Innovation?

When I heard the two actual tracks I could hear plagiarism. The rhythm, melody and sound effects were identical to the Marvin Gaye classic “Got to Give It Up” which in itself is mostly rhythm and sound effects with a small amount of melody. Song copyrights were made for this very reason.

Room for Debate, NYT

Market Structure & Incentives to Invent

Let's look at two types of markets: perfect competition and monopoly.

•a single inventor is considering investing in R&D in order to achieve a cost-reducing invention of a particular size.

•The inventor is not concerned about competition from other inventors, and enjoys complete protection from imitation.

What are the payoffs to invention in the competitive case and in the monopoly case?

Market Structure & Incentives to Invent

New Product (often from R&D)

New Process lowers production costs

“Minor invention”: costs drops may not be big enough to induce price reductions

“Major invention:” drive out previous (incumbent) tech

Results in price reduction

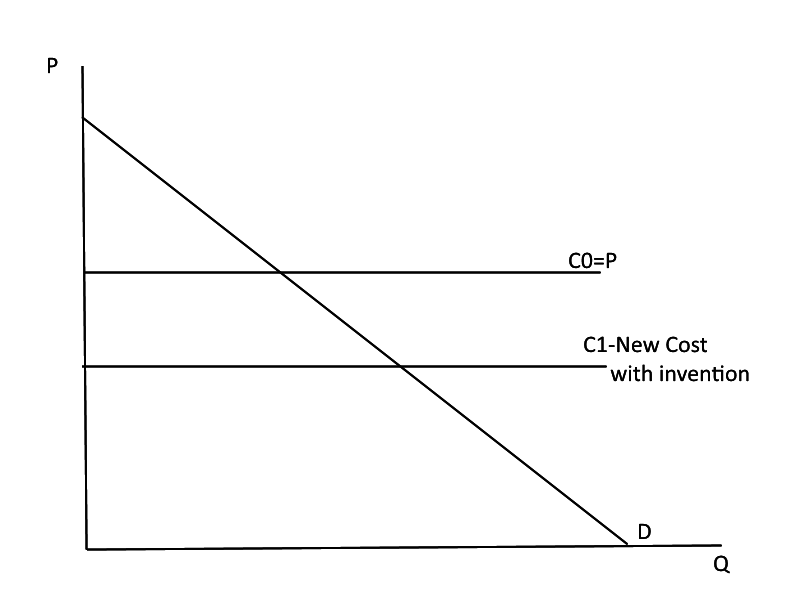

Perfect Competition

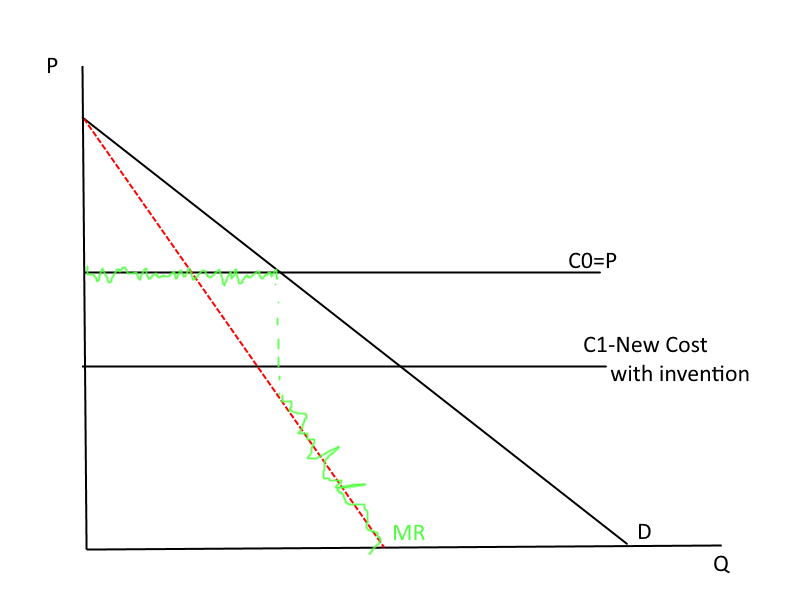

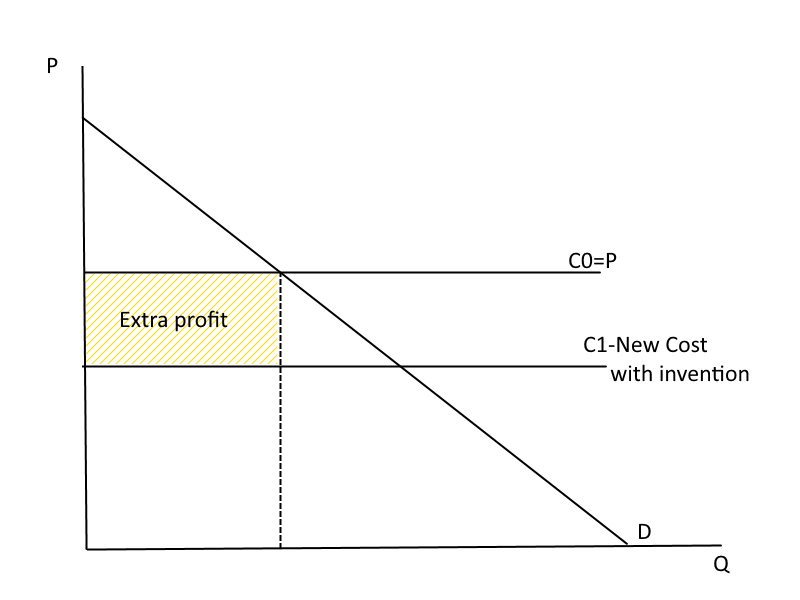

Perfect Competition--everyone else has cost C0, but the innovator has cost C1. What is the advantage to the innovator?

Perfect Competition

Same Q, but lower cost. But wait--why not increase Q?

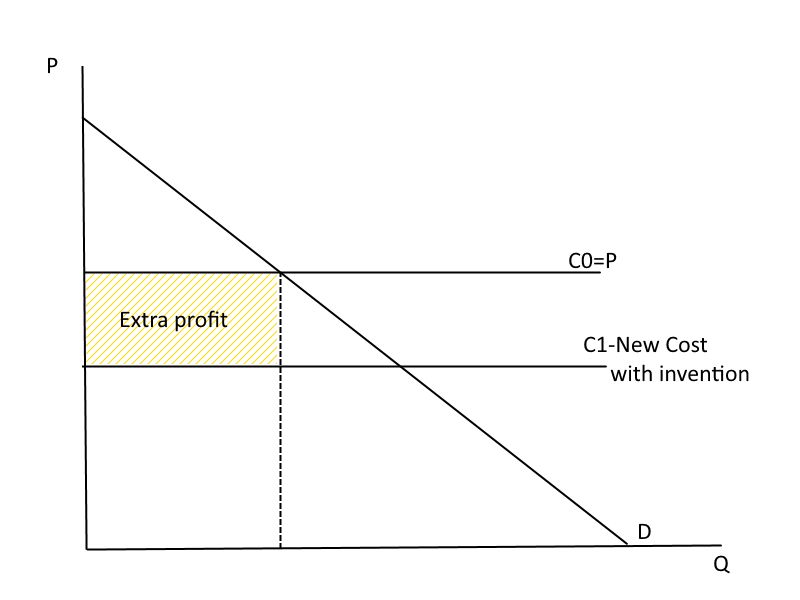

Perfect Competition

Change in revenue associated with changing the price

Perfect Competition

The innovator could sell more by lowering the price--but the MR would be below MC (C1)--so his/her profit is higher if he/she stays at the old quantity and price.

Perfect Competition

Put differently--the innovator does better by remaining in the "perfect competition" world but reaping the benefits of being exceptionally low cost.

Perfect Competition

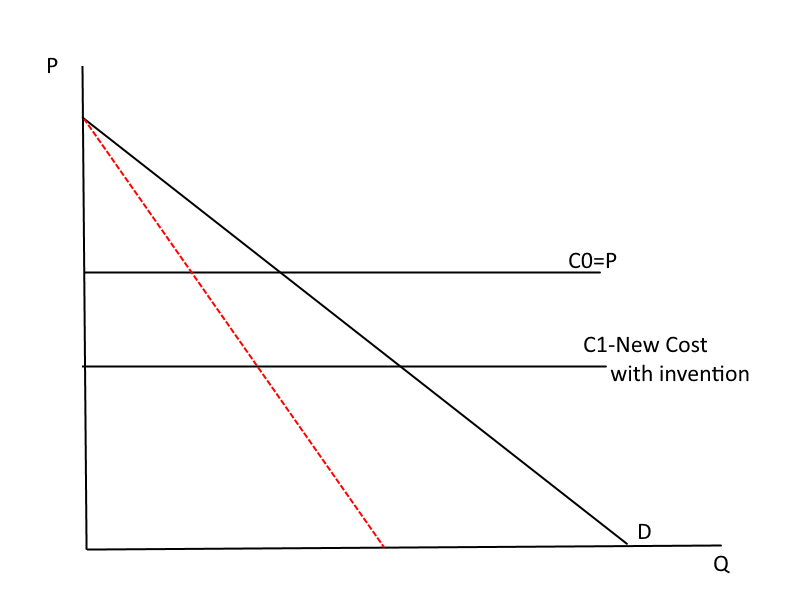

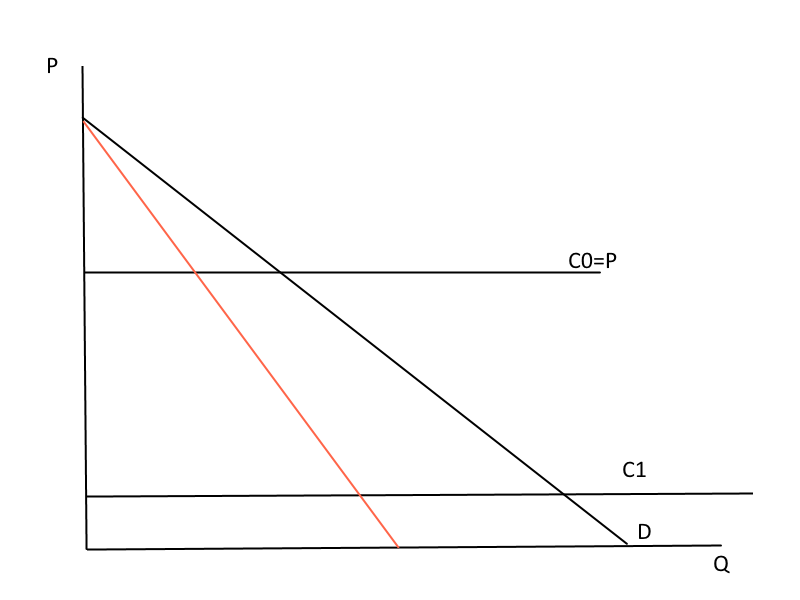

What if innovation is so extreme that it lowers cost to C1?

Perfect Competition

Now it makes sense to lower price--what will the new price be? What will happen to the rivals?

Perfect Competition

Let's focus on this case for now.

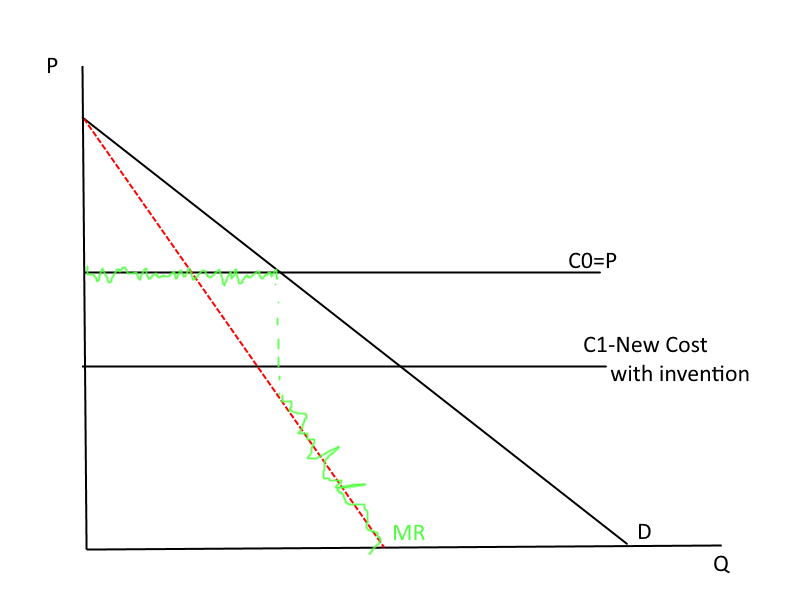

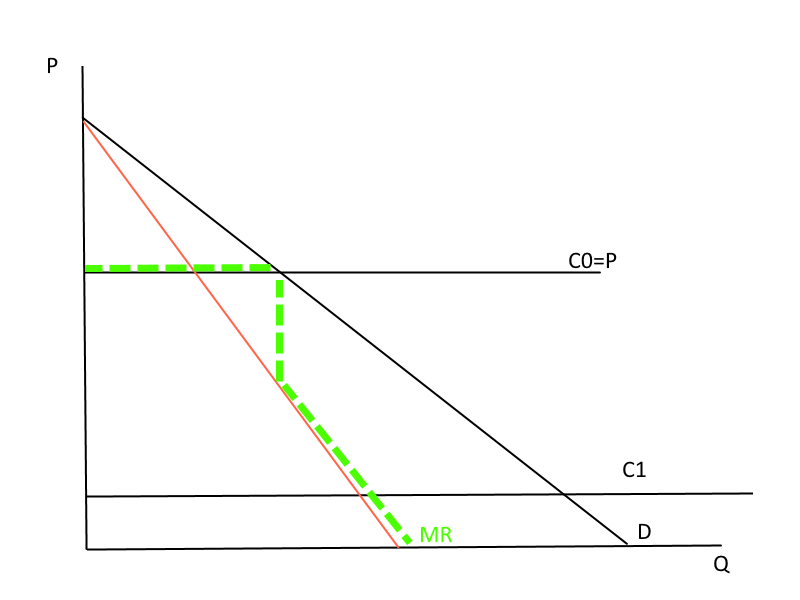

Monopoly

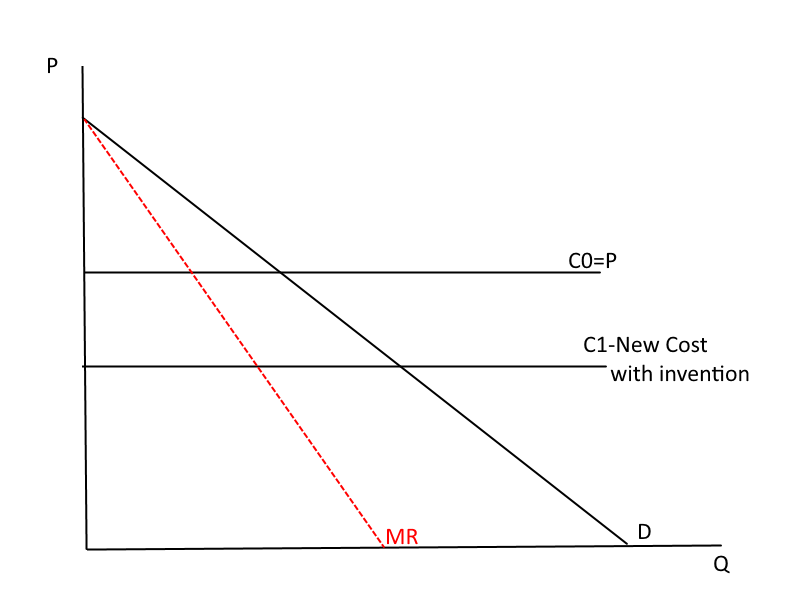

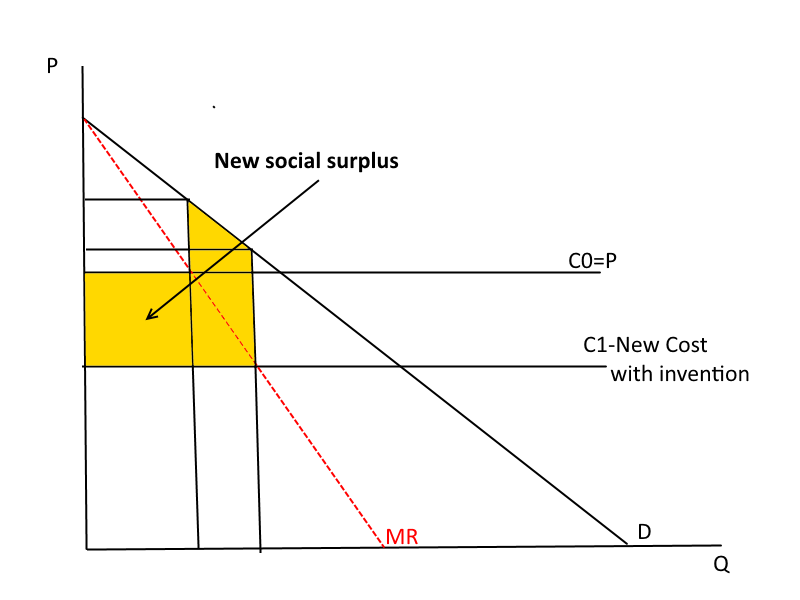

This is the same innovation but for a monopolist. Where was the old price/profit? What is the new price/profit?

Monopoly

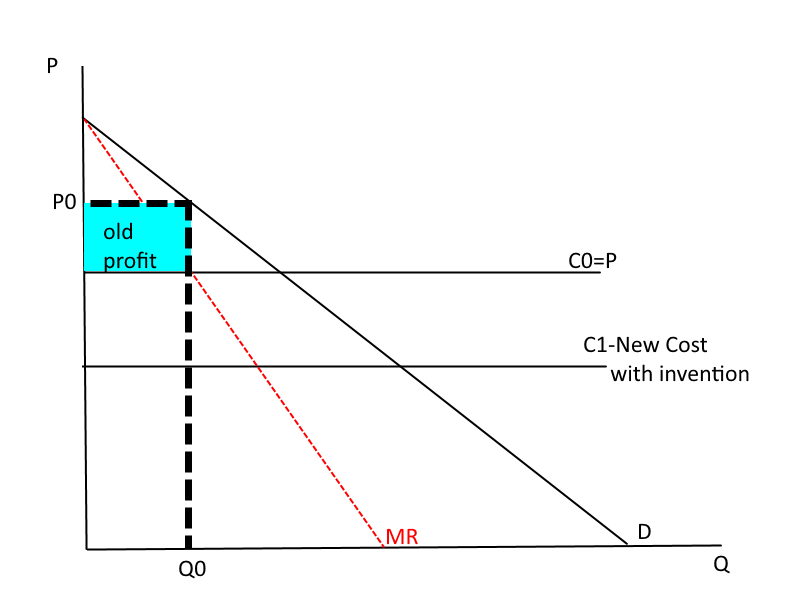

Profit before innovation

Monopoly

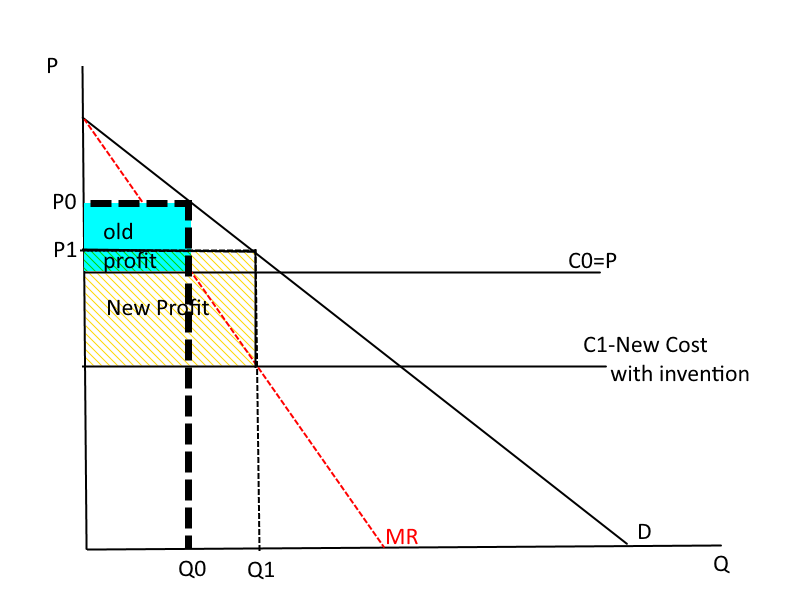

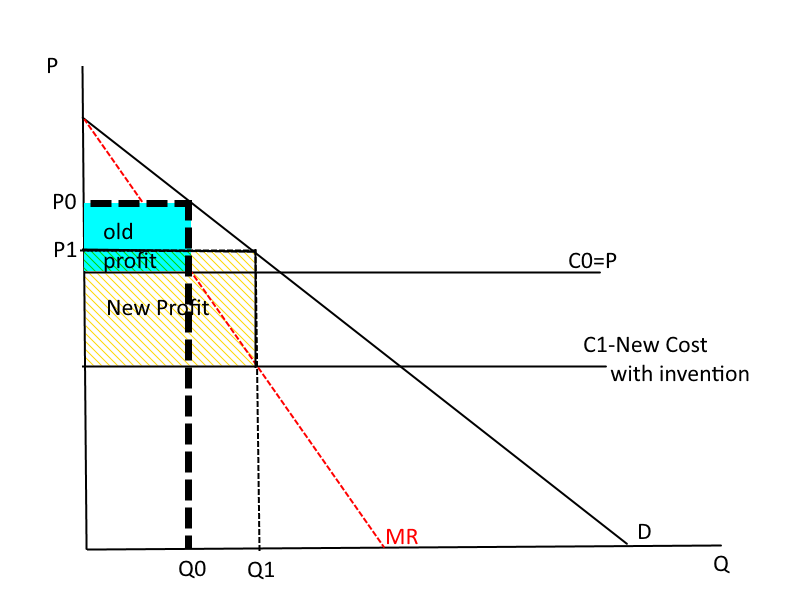

Profit after innovation. Change in profit is New Profit - Old Profit

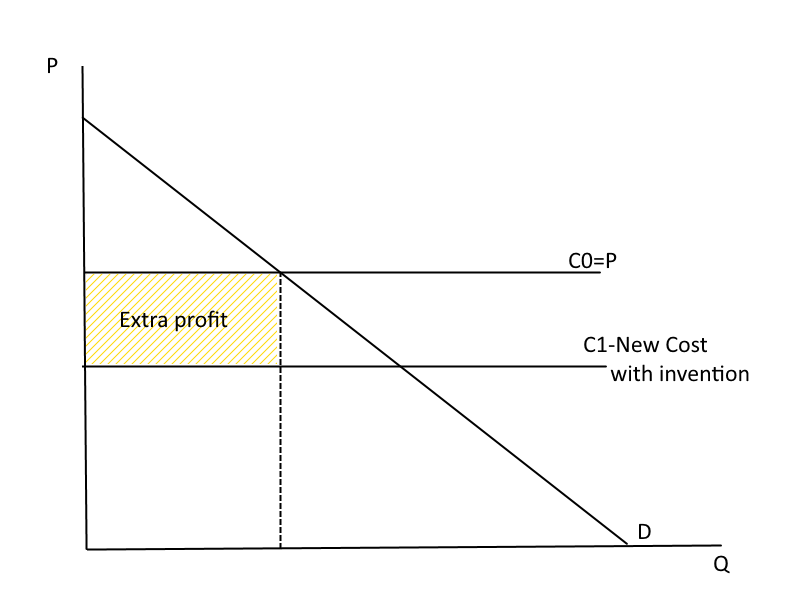

Monopoly v Competition

So, who has more to gain from innovation?

Monopoly v Competition

For minor inventions the incentive to invent is greater for the perfectly competitive firm than for the monopoly firm.

Key Result #1:

Monopoly v Competition

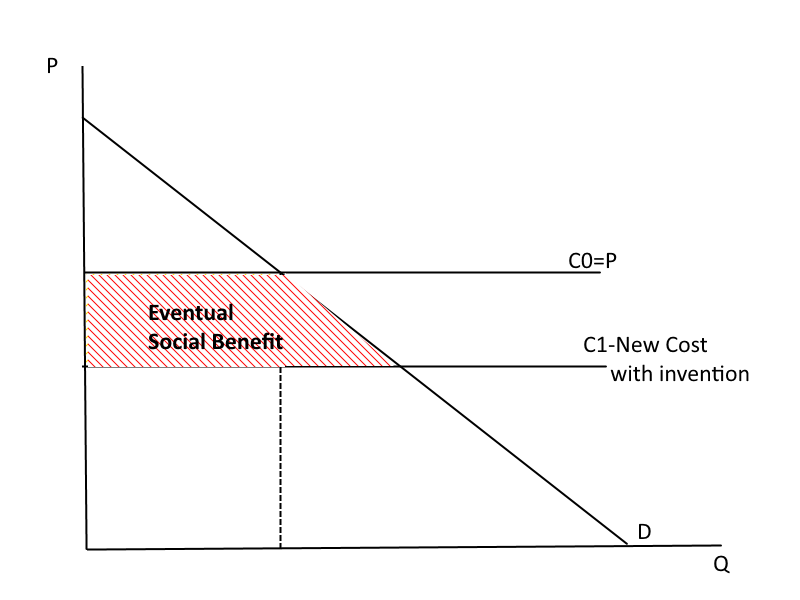

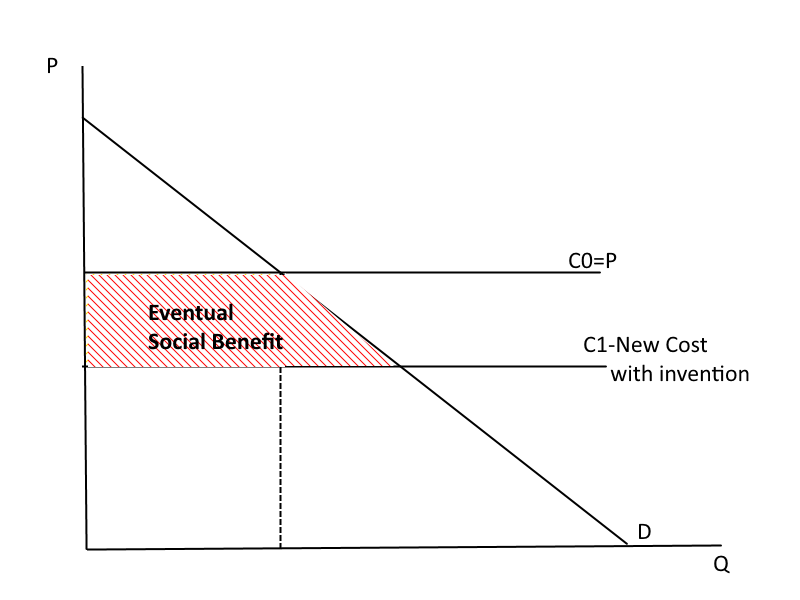

Furthermore, if we think the invention will eventually be made to other firms in the industry (e.g., when the patent expires), the social benefit for an innovation in a competitive market will be:

Monopoly v Competition

Which is larger: the benefit to society, or the benefit to the inventor himself/herself?

Monopoly v Competition

How about with Monopoly?

Monopoly v Competition

Key Result #2:

Some of the new surplus from innovation will always accrue to the consumers, not to the innovator. Social benefit from invention exceeds the incentive to invent both under perfect competition (I+II) and under monopoly (< I+II )

Practice Problem

Assume the market demand for shoes is Q=100−P and that MC=60. There are two cases:

- C: the industry is organized competitively

- M: the industry is organized as a monopoly

In each case an invention lowers MC to 50.

Assume that there is no rivalry to make the invention:

- C: the inventor has a patent of infinite life

- M: the inventor is the existing monopolist and entry is barred.

Practice Problem

Find the initial price and quantity equilibria in the two cases.

What is the higher profit that the inventor in perfect competition could expect from its lower cost production process?

What is the higher profit that the inventor int he monopoly market can expect from its lower cost production process?

In perfect competition, what would be the increase in total economic surplus if no patent were granted and the invention was immediately copied?

Demand: Q=100-P; Old MC=60, New MC=50