Applied Microeconomics

Lecture 5

BE 300

Plan for Today

An Economist's View of Costs

Sunk Cost vs. Psychology

From reading: How to Walk Away, The Atlantic, 5/14/2013

“Sunk costs are the investments that you've put into something that you can't get back out. …the years you spent training for a profession you hate, or waiting for your commitment-phobic boyfriend to propose. … it shouldn't matter how much time and effort you've already put into something. If your job or your boyfriend have taken up some of the best years of your life, it doesn't make sense to let them use up the years you've got left "

Sunk Cost

Suppose you are the CEO of an aviation company that spent $9 million developing a plane undetectable by radar. A rival company announces their own completed radar-blank plane, which is both superior in performance and lower in cost.

Question: Do you invest the remaining $1 million and finish your company's plane, or cut your losses and move on?

In studies, why do some test subjects opt to continue investing in the plane?

Plan for Today

Start Module 3: Cost Fundamentals

Revisit: Opportunity Costs & Sunk Costs

Cost Concepts

Short-run Costs

Case: Franchisee McCosts (class discussion)

Sunk Cost

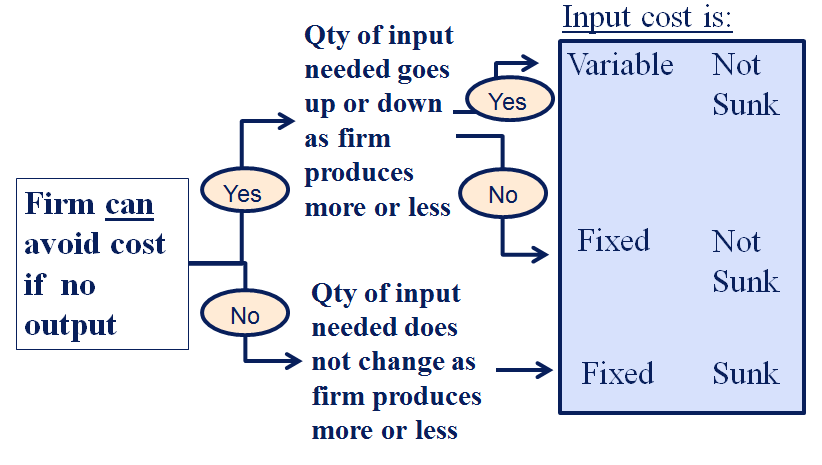

Sunk cost: A past expenditure that cannot be recovered

Examples:

Price paid for specialized equipment that has no alternative use

Past expenditures on R & D

Sunk costs should be ignored in making decisions focus on current and future values only even for equipment or assets that have an alternative use, the cost of purchase is irrelevant – only the value today matters in making decisions.

Opportunity Cost

The implicit costs associated with using a resource in a particular endeavor; measured by what is given up by not using this resource in its next best alternative use.

We count those in economics even if they don’t show up on financial statements

Examples:

- The cost of your time

- The cost of capital you invest in a business

- The cost of using assets in another way

Thinking Like an Economist

From a 1989 internal study of McDonald’s franchises, we have the following data:

- Item A: On average, franchisees earned $72,000 on their last job.

- Item B: All franchisees must go through 2000 hours of training (uncompensated), which at the wage of their previous job comes to $75,000.

Why is Item A an opportunity cost?

Why is Item B a sunk cost?

Costs

Opportunity costs are often hidden, but are appropriately included in any profit maximizing decisions .

- Just the opposite is often true of sunk costs ─ while they are usually visible, once incurred, are not relevant for any profit maximizing decisions.

- For an asset, the cost of purchase is irrelevant (unless you can return the asset for the purchase price) ─ only opportunity cost matters in making decisions.

Outsource your way to Success

What tasks to Profs. Nakamura and Steinsson outsource and why?

With Craigslist, Amazon Mechanical Turk or TaskRabbit available – why don’t we observe more outsourcing?

Costs

Ernie & Bert are Mumford and Sons fans who live in Ann Arbor. One Friday they had planned to go see the band at the Palace in Auburn Hills (near Detroit). Ernie bought a ticket in advance at a local Ticketmaster outlet, while Bert had planned to buy his ticket at the venue. The day of the concert there is a terrible storm, which causes tremendous traffic jams throughout SEMichigan.If the two friends have the same tastes and are both rational, is one of them more likely to attend the concert than the other?

[Assume each person's choices do not affect the other's--that is, they do not need to go to the concert together]

Costs

Rational economic behavior: go to the concert if benefit from attending (U) exceeds the cost (C)

Since B & E have the same tastes, UB = UE

C = ticket cost (T) + “hassle cost” of getting there (H)

For Ernie: T is a sunk cost at this point

Go if U > H

For Bert: T is not sunk

Go if U > T + H

Since the relevant cost is lower for Ernie, he is more likely to go.

Costs

The storm finally lets off so Ernie and Bert decide to drive to the concert together. They arrive to discover the show is sold out and tickets like the one for which Ernie paid $30 are now being sold by ticket scalpers for $200.

If the two friends have the same tastes and are both rational, is one of them more likely to attend the concert than the other?

Assume again that the other person’s decision does not affect choice, and that there is no judicial or other risk to scalping tickets.

Costs

Still same rule: go to the concert if U > C

They still have the same tastes, so UB = UE

Since they are now there, the “hassle cost” of getting there, H, is sunk for both of them.

For Ernie, T is also sunk

For Bert, what is C now?

How about for Ernie?

Costs

Ernie now faces an opportunity cost that is equivalent to Bert’s explicit cost for the ticket.

Since their benefits and costs looking forward are the same, the two friends should make the same decision.

Avoid Sloppy Thinking!

Management Application

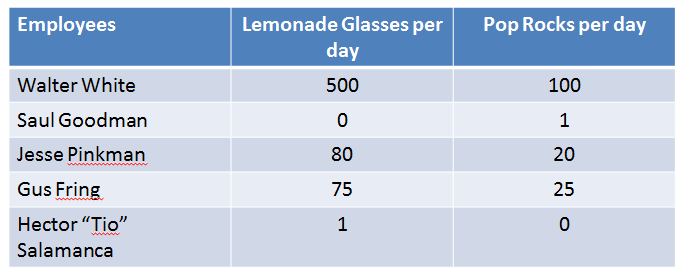

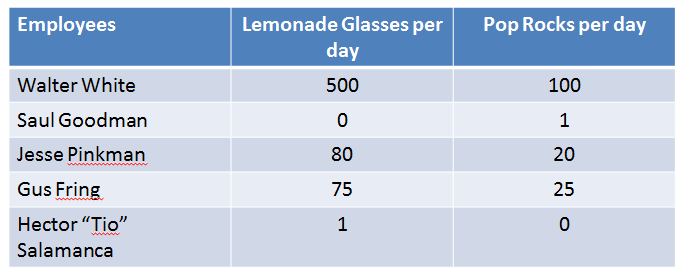

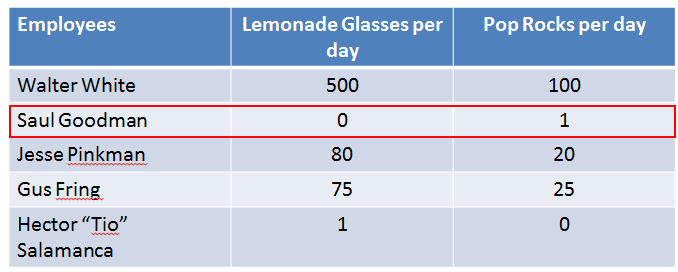

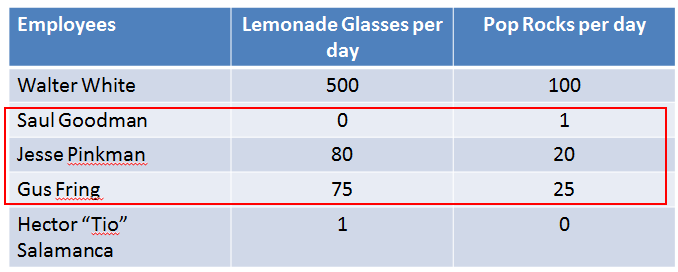

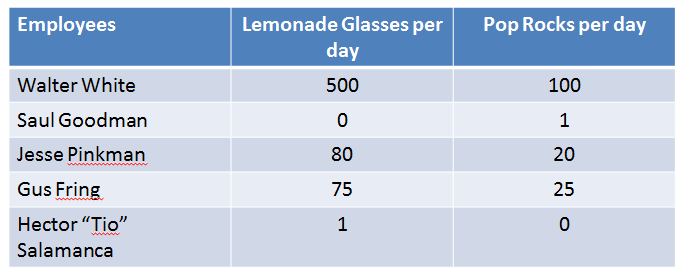

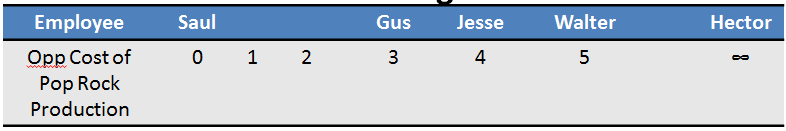

Management application: assigning employees to different tasks using opportunity cost.You have five employees and produce Lemonade and Pop Rocks at your Albuquerque plant.

Costs Application

Suppose a glass of lemonade sells for $1 and a bag of Pop Rocks sells for $1. Everyone is currently working on lemonade.

Whom (if anyone) should you move to the Pop Rocks production line?

Cost Application

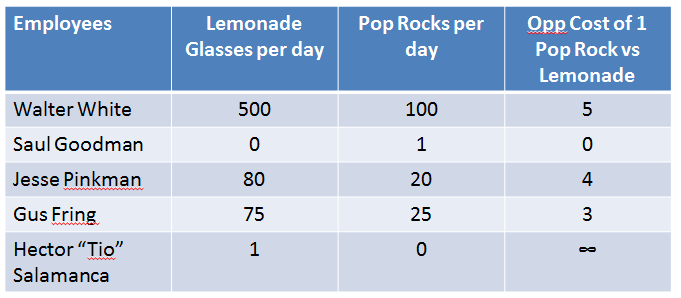

Now, the price of pop rocks has risen to $4. Who would you want to work on Pop Rocks?

Cost Application

If the price of Pop Rocks is $10?

Cost Application

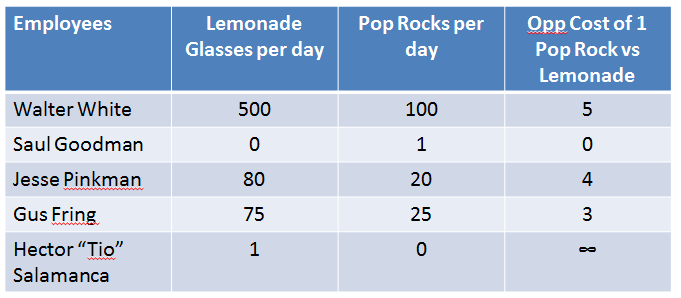

What is the opportunity cost of producing a pop rock in terms of the lemonade production forgone for Walter White?

Cost Application

Saul is terrible and making lemonade (he drinks most of it and spills the rest) so he is always the first person on the Pop Rocks production line.

Who’s next? Who’s last? Why?

Cost Application

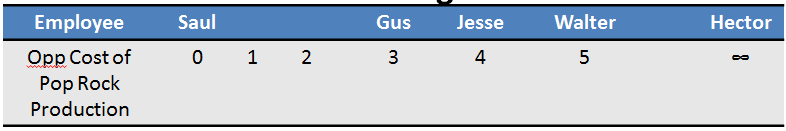

Good managers take advantage of comparative advantage.

Walter is the best at lemonade AND pop rock production, but we only move him to pop rock production when the price of pop rocks is at least $5.

Assign workers with lowest opportunity cost to pop rock production first. STOP when opportunity cost is greater than price of pop rocks.

Cost Application

Application of the principle of comparative advantage – specialize according to relative opportunity costs not absolute productivity to realize gains from trade .

Walter White is better at making Pop Rocks than anyone else--but his opportunity cost is high (because he is also productive at making lemonade)

Cost Application

This works for any relative prices (not only when lemonade costs $1). Rank workers by opportunity cost, and then compare the ratio of prices (Price of Pop Rocks divided by Price of Lemonade) to opportunity cost.

When lemonade is selling for $3 and pop rocks are selling for $21, who should be working on pop rocks?

What if the price of lemonade rises to $7?

Short vs Long Run

The short run is the amount of time within which firms are unable to change the quantity of some of the inputs they use.

- Usually it is physical capital (number and size of plants, investment in equipment) that the firm cannot change in the short run

By contrast, the long run is when firms can change the quantity of all the inputs they use, including the size and number of their plants

- all costs are “avoidable” in the long run

What is short or long run varies by industry.

From Short Run to Long Run...

and capacity has been put into place,

we move from

the long-run (investment/planning) horizon

to

the short-run (operation) horizon

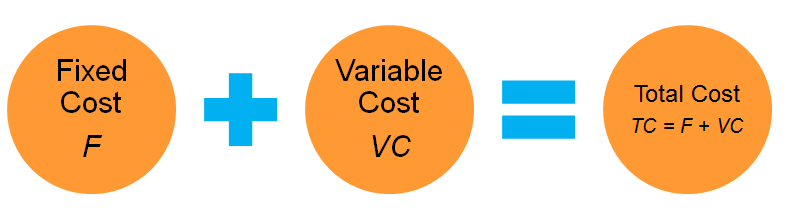

Short Run Costs

Total Cost (TC): the sum of fixed and variable costs in SR

Fixed Cost (F): does not vary with the level of output

- includes expenditures on land, office space, production facilities, and other overhead expenses; are often sunk costs, but not always.

Variable Cost (VC) changes as the quantity of output changes

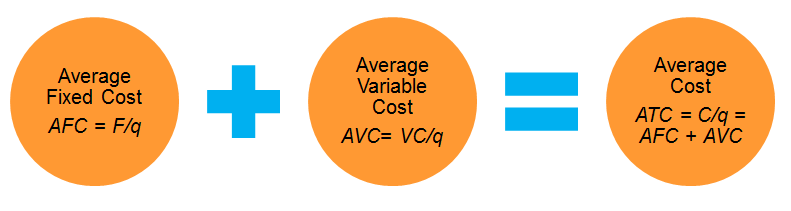

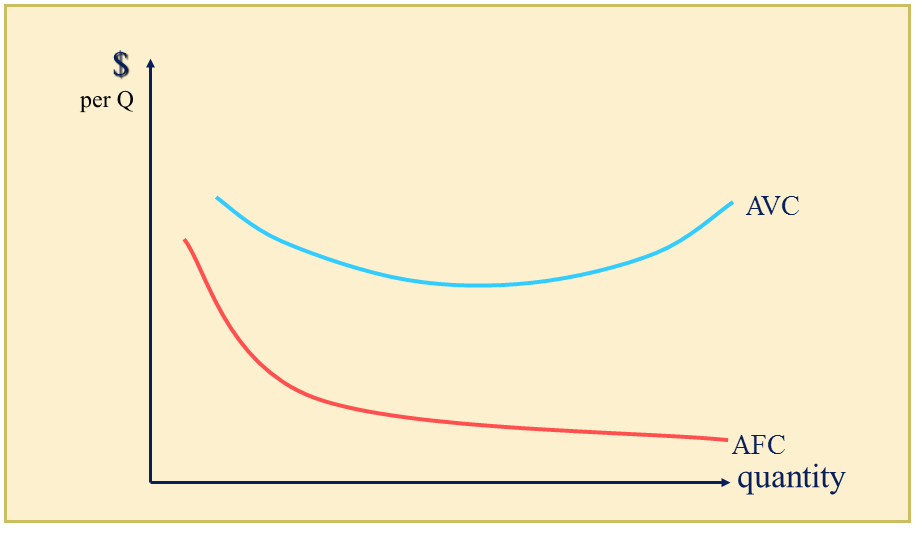

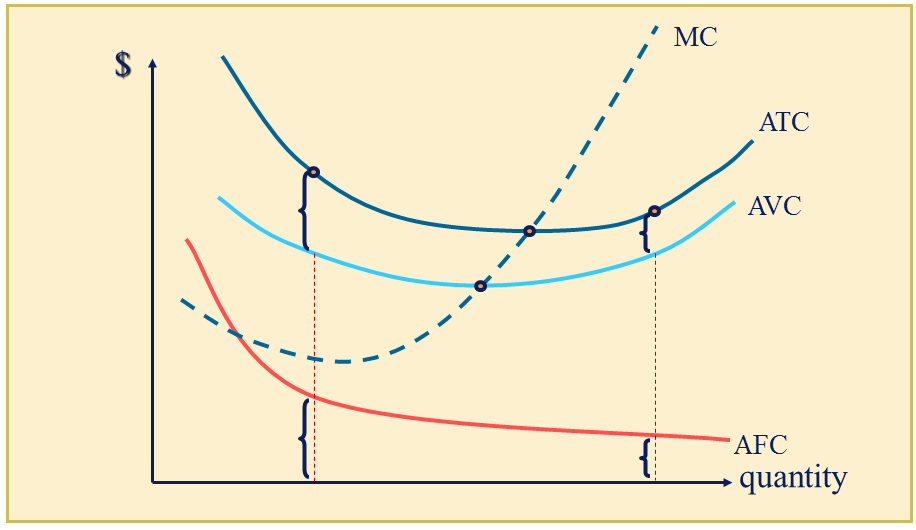

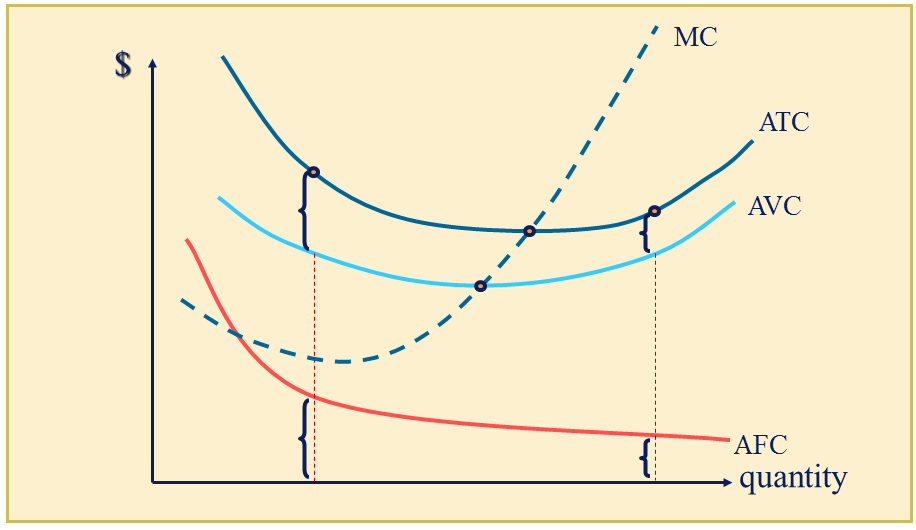

F and VC should be based on inputs’ opportunity costs.Short Run Costs

- Average Fixed Cost (AFC) falls as output rises because the fixed cost is spread over more units.

- Average Variable Cost (AVC) or variable cost per unit of output may either increase or decrease as output rises.

- Average Total Cost (ATC) or average total cost may either increase or decrease as output rises.

Short Run Marginal Costs

Marginal Cost: MC = ΔTC/Δq

Marginal cost (MC) is the amount by which a firm’s cost changes if the firm produces one more unit of output; ∆TC is the change in cost when the change in output, ∆q, is 1 unit.

Short Run Marginal Costs

Marginal cost also equals the change in variable cost from a one-unit increase in output.

Fixed costs don’t change with output so can compute MC using TC or VC functions.

Marginal Cost using Calculus: MC = dTC/dq = dVC/dq

Marginal cost is the rate of change of cost as we make a small change in output. MC=dVC/dq because dF/dq=0.

Quick review: derivatives of a polynomial

If the function is y=10+2*x^2 + x^3, what is the derivative of y wrt x?

dy/dx=4x+3x^2

Franchise McCost

Franchise Costs

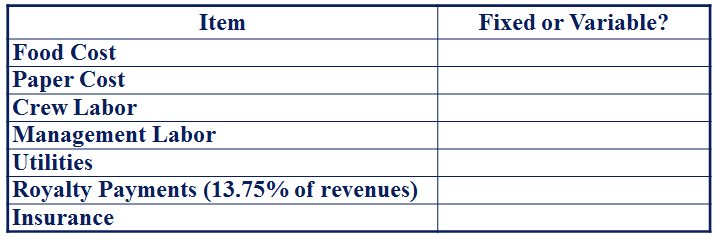

Consider a typical McDonalds franchise. Classify each of the itemized costs in the following table as variable or fixed. (Assume that these are all recurring expenses and therefore there are no sunk costs among the itemized expenses.)

Franchise Costs

Franchise Costs

Variable: Food, paper, crew labor, royalty payments*

Fixed: management labor, utilities, insurance**

* Some part of the utilities could be considered to be a variable cost; however, McDonald’s usually runs all the equipment all the time, regardless of output.

** Some part of crew labor could be considered a fixed cost, e.g., if a “skeleton crew” or a minimum number of staff must be working whenever the store is open. However, for most McDonald’s restaurants management will often staff the restaurant when required during the off-hours.

Cost Functions: C=f(Q)

The cost function depends on: the firm’s production technology & input prices

Production technologies vary across industries & over time.

- The “typical” costs curves used to illustrate will not be a good fit for all cases

Example: Airline Cost Functions

“If airlines know there will be a surge of passengers during the holidays, why don’t they add capacity in the form of extra flights?” --“Why don’t airlines just add more flights during he holidays” CNBC 11/27/2013

Fixed cost barriers?

Variable cost barriers?

Is adding a plane a fixed or variable cost?

What margins can they adjust in the short-run?

Cost Functions

Cost Functions

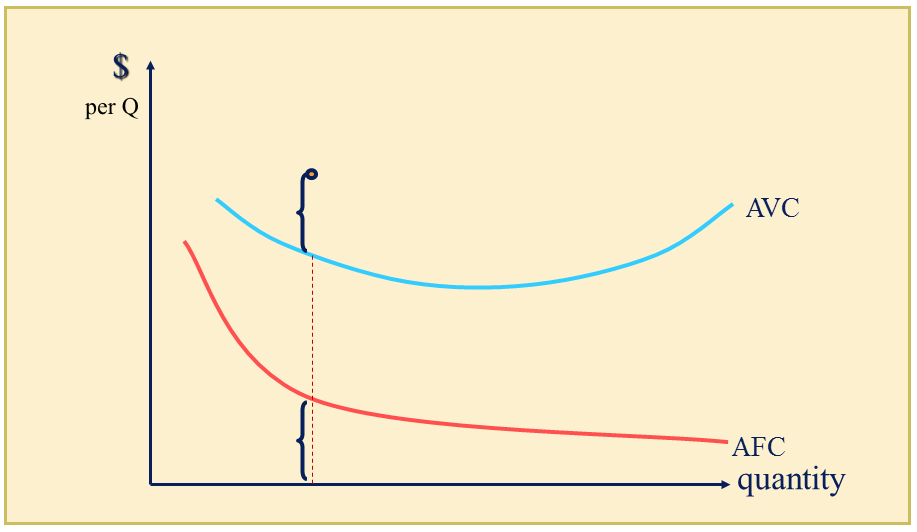

Remember, AVC+AFC=??

Cost Functions

AVC+AFC=ATC

(The vertical distance between ATC and AVC is AFC).

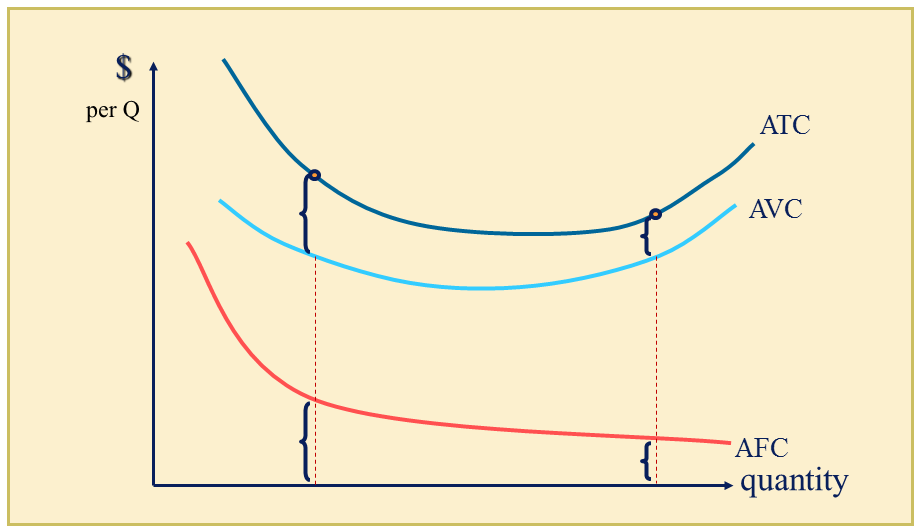

Cost Functions

Marginal cost goes through the minimum of the ATC and AVC curves.

Cost Functions

When MC is below ATC--ATC slopes downward (is decreasing as Q increases). When MC is above ATC--ATC slopes upward.

Cost Functions

“Marginal pulls the average”

If MC < ATC, then ATC declines

If MC > ATC, then ATC increases

Same holds for AVC

Simple numerical example

Take the average of 1, 2, and 3: (1+2+3)/3 = 2

Add 4 and recalculate: (1+2+3+4)/4 = 2.5

Add 1 and recalculate: (1+2+3+1)/4 = 1.75

Add 2 and recalculate: (1+2+3+2)/4 = 2

Add 2 and recalculate: (1+2+3+2+2)/5=2

Cost Functions

Why would short-run marginal costs (and average costs) go up at some point when we increase total output?

Cost Functions

When increasing amounts of one factor of production are employed along with a fixed amount of some other factor, after some point, the resulting increases in output become smaller and smaller.

Diminishing Marginal Returns only applies in the short run.

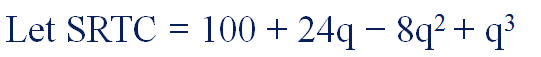

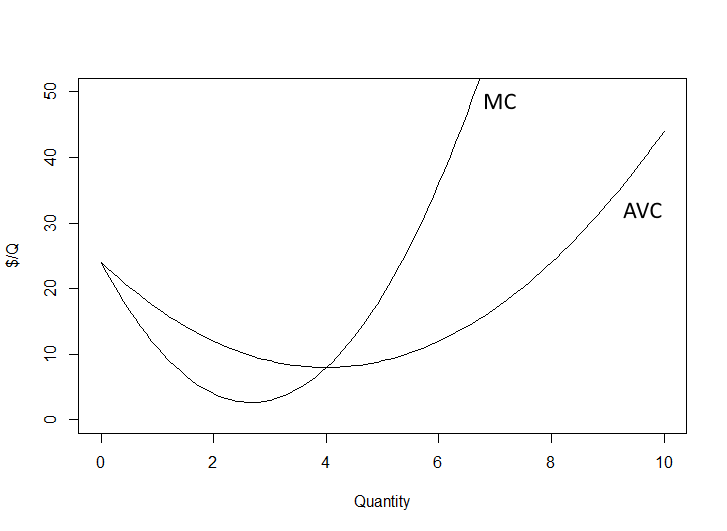

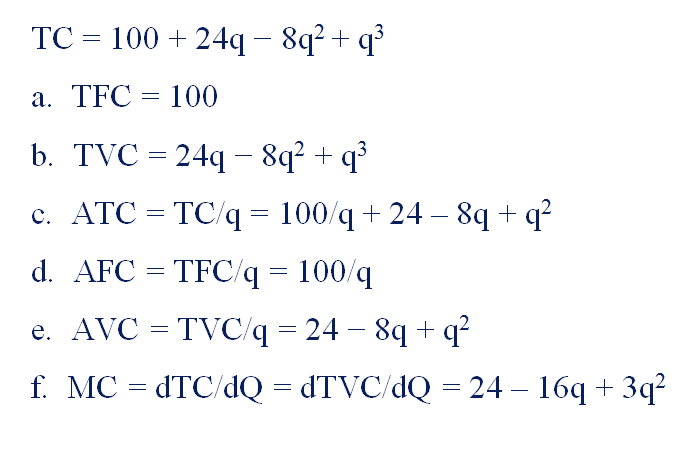

Cost Function Exercise #1

a. What is FC?

b. What is VC?

c. What is ATC?

d. What is AFC?

e. What is AVC?

f. What is MC?

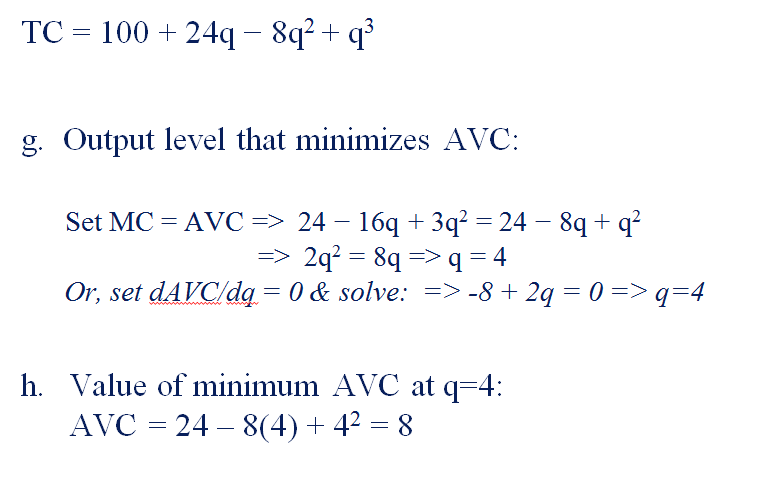

g. At what quantity is AVC minimized?

h. What is minimum AVC there?

Cost Functions Exercise

Cost Functions Exercise

Cost Functions Exercise

Coming Up

THURSDAY Jan. 29 (Costs)

Textbook: Cost Topics—pp. 132 – 133, Ch. 5.4 – 5.5, pp. 176 – 179, Ch. 6.4 – 6.5, Ch. 7.2

Write up of “Moo’ve on Out?” case

TUESDAY Feb. 3 (Competitive Supply & Market Analysis)

Textbook: Ch. 2 intro, 2.3 – 2.4, 2.6; Ch. 7.5; Ch. 8 intro, 8.1–8.3.

For the case: Moo’ve on Out

Calculating Profits:- Profit = TR – TC, or also

- Profit = (Q*AvgRev) – (Q*AvgCost)

- Recall economists include opportunity costs and accountants do not

Make one more unit?

- Compare marginal benefit to marginal cost.

- MB – MC = add’l profit from one more unit

Apply opportunity cost principles

- recall opp cost depends on who is doing the work

- unmeasured benefits/costs of activities

- In long run all costs are avoidable