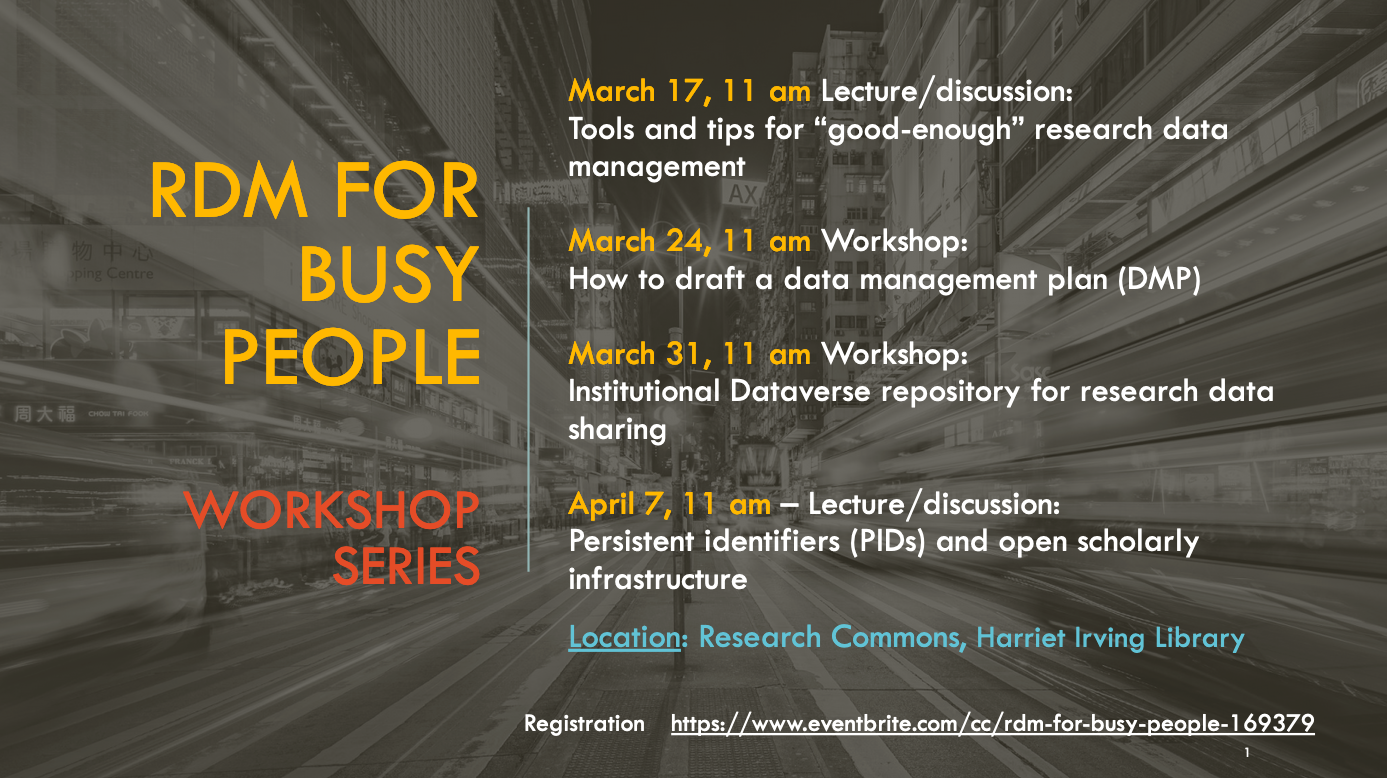

persistent identifiers & open scholarly infrastructure

a primer for the rdm for busy people series.

mike nason

open scholarship & publishing librarian @ unb libraries

crossref & metadata liaison @ pkp

persistent identifiers as open scholarly infrastructure

a primer for the rdm for busy people series.

mike nason

open scholarship & publishing librarian @ unb libraries

crossref & metadata liaison @ pkp

part i // ~60m

11:00-12:00

overview of persistent identifiers, open scholarly infrastructure, and what researchers need to know about them.

the talk will cover DOIs, ORCID, ROR, and other players/service providers in the PID space.

part ii // ~30m

12:15-12:45

overview of the services and features of ORCID, including information on signing up for the service and adding your publications/works to your profile.

introductions

it's me, mike! hello! i hope you're well, despite [gestures broadly] everything.

i'm your open scholarship & publishing librarian.

in short, ...

... my job is about helping you make the results of your research as accessible to the public (or, relevant research communities) as you need them to be, whether that's due to funding mandates, personal interest, or a sort of proactive capitulation.

i am here to help you. it's, like, specifically built into the cba (16c.02). it is what librarians are for.

research data management

tri-agency oa requirements

open access publishing

scholar profiles

repositories

digital publishing

open educational resources

open infrastructure

persistent identifiers

scholarly publishing

scholarly communications

part i

i'd like for you to keep a thought on the backburner.

pids are in the drinking water of scholarly publishing

i'll come back to this.

like, a lot.

part i

overview of persistent identifiers, open scholarly infrastructure, and what researchers need to know about them.

the talk will cover DOIs, ORCID, ROR, and other players/service providers in the PID space.

agenda

- what is a persistent identifier?

- what is a registration agency?

- what is open scholarly infrastructure?

- what pids should i care about?

let's start small.

the doi

dois

dois are ubiquitous. we see them all over the place:

- in references/bibliographies

- on article/journal websites

- in repositories

- on published datasets

- links on twitter or researchgate or academia dot edu or, or, or...

and, we probably know one handy thing about them:

if you click on a doi that looks like a link, it will take you to the thing.

dois

dois are the most prominent persistent identifier.

they are also, arguably, the most important persistent identifier.

how a doi works

a doi is made up of two chunks. a prefix, and a suffix.

prefix

10.4324

suffix

9780203051238-5

together, these make the doi 10.4324/9780203051238-5

how a doi works

prefixes and suffixes mean different things.

prefix

10.4324

a prefix is usually associated with a publisher or organization. dois for that organization will usually have the same prefix.

suffix

9780203051238-5

a suffix is meant to be a machine-readable (not human-readable), opaque, unique string that is specific to the singular work to which it is assigned.

(we'll talk more about this)

how a doi works

if i prepend a doi with https://doi.org/, it turns into a url.

https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203051238-5

clicking this will redirect me to the publication this doi is associated with. the process of a doi redirecting you to a publication is called resolution.

what's "resolution"?

how doi resolution works

dois aren't just like a bit.ly link or tiny.url. if you're not familiar with these services, they will swap out a very large and unwieldy link so you can share something that isn't enormous.

for example: https://bit.ly/35LaEXj

this is a bit.ly link for this talk

the actual url for this talk is: https://slides.com/ahemnason/persistent-identifiers-pids-and-open-scholarly-infrastructure/

bit.ly and tiny.url are both basic redirects.

how doi resolution works

a doi, though, is a lot more than a redirect. a doi is a reference to an entire publication record. that publication record is full of metadata.

one of these metadata elements is the publication's url.

when you resolve a doi by clicking on it:

- the record is accessed

- the stored url is retrieved

- you are sent to the stored url

the url can be updated by the publisher. the doi stays the same.

neat!

it is.

surely, there is more to it?

🤔

congratulations, you now know more about dois than a frankly surprising amount of people.

and, by extension, you now know more about pids than a frankly surprising amount of people.

so, dois are pids?

dois are definitely pids.

what a pid is

an identifier // a label which gives a unique name/label to an entity: a person, place, or thing.

persistent // long-lasting

are you seriously about to tell me what an identifier is?

what an identifier is

absolutely. an identifier is a unique string of characters assigned to something, someplace, or someone that can be used to identify it.

- social insurance number

- driver's license number

- medicare number

- license plate number

- student number

we are assigned identifiers all the time. we (ideally) carry "ID".

what an identifier is

identifiers typically refer to physical objects and are often created/managed locally. they're useful for record-keeping and data retrieval/searchability. they're useful for disambiguation, too!

- unb student id is only a useful label for unb students.

- social insurance numbers are provided federally.

- medicare numbers are provided provincially.

- a license plate is only a label for a current, registered car.

there is more than one mike nason in canada, but only one of them has my social insurance number (i hope).

dois are identifiers

doi is an acroynm for:

Digital Object Identifier

did you just spend three slides telling me what an id is?

yes.

but that's because pids share the same benefits! they're good for disambiguation, data retrieval, searchability...

we've scratched the surface a bit on what a doi does, but url storage and redirection is just one benefit for one kind of pid.

for example

i might write my own name as:

- Mike Nason

- Michael Nason

- Michael Thomas William Nason

- M. Nason

- mnason

- ahemnason

and! there may be more than one of any of these! the more variations and folks with the same name there are, the harder it is to find the stuff i've done. a pid for people would make attribution and discovery easier.

ok, so what about persistence?

what a persistent identifier is

persistent identifiers most frequently refer to digital things. traditionally, we share or locate digital things using a link (a url).

url // uniform resource locator

(https://www.example.com/index.html)

we know that urls break all the time, for lots of different reasons.

what a persistent identifier does

a url can tell you where something was when you read it. if you bookmark that url or put it in print, you're assuming that it will still work later. this is not guaranteed!

but, as we discussed earlier, using dois i can update the location if the content moves. i can provide a persistent link to a record that contains a url.

the id is persistent. where it directs me may change.

a doi is persistent. where the doi resolves may change.

what a persistent identifier does

so, imagine finding the citation for this work in a bibliography... which of these two will be more useful if the content moves from the website it is currently on?

Smiraglia, R. (2005). Metadata: A Cataloger's Primer (1st ed.). Routledge. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/mono/10.4324/9780203051238/metadata-richard-smiraglia

Smiraglia, R. (2005). Metadata: A Cataloger's Primer (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203051238

what about

orcid?

what orcid is

ORCID stands for "open researcher and contributor id"

ORCID is also the name of the not-for-profit organization that provides ORCID IDs, maintains the service, and develops the website and API

if you're the kind of person who is bothered when people say "pin number", you'll hate orcid. no one says "ORC IDs".

what is an orcid?

we typically call them "orcid ids" or "orcids"

what an orcid id is

orcid ids are a kind of pid.

what an orcid is

first and foremost, orcid ids help consistently and properly identify the authors of works no matter what their name is, was, or will be

nearly every publisher can take an orcid id as metadata associated with a publication

this metadata can save people time

for example

i might write my own name as:

- Mike Nason

- Michael Nason

- Michael Thomas William Nason

- M. Nason

- mnason

- ahemnason

orcid also provides users with what's known as an orcid profile

when you hear someone talk about a scholar profile or a researcher profile, they are probably talking about orcid, scopus id, researcher id, or google scholar (but they might be talking about something else entirely)

i've done a handful of talks on this, links for them are on the next slide

what a persistent identifier does

pids make things easier to find, track, share, and access!

and so, "persistent identifier"

a unique, unchanging, identifier representing an object (digital or otherwise) that can direct a user, unambiguously, to that object's current location.

a pid cannot just do this inherently, though...

pids require a third party

often, folks use the phrase "minting a doi" to describe the assignment of a doi to a work. i see this a lot. a journal editor might say to me, "i made all these dois but they don't work! i just get an error!"

a publisher can mint pids and provide them to you, but they need a third party to be at all useful.

to work, a pid needs to be registered with a pid registration agency.

what's a registration agency?

registration agencies

persistent identifiers are managed by registration agencies (typically international not-for-profits) that store records/metadata, facilitate resolution requests, and may or may not offer other services based on membership. they do much of this through APIs.

there are a lot of registration agencies!

registration agencies

it's important to know that registration agencies differ in mandate, governance, scope, service, supported objects, membership terms, and feature set.

they also, often, work together and share data.

let's review

the field

pids for scholarly works

Crossref (DOI)

most scholarly publishers are crossref members. at the time i wrote this (1pm, april 6th) crossref had 134,294,189 dois registered with their service.

crossref are a big deal.

articles

proceedings

monographs

*datasets

funding agencies

grants

reports

standards

preprints

pids for scholarly works

Datacite (DOI)

while some scholarly publishers use datacite for article dois, it is much more commonly used in data/institutional/disciplinary repositories.

datacite and crossref work together to connect research data to publications.

software

datasets

collections

audio/visual

event

model

*publications

pids for researchers

ORCID (ISNE)

Scopus ID

WoS Researcher ID

orcid are the go-to here, with scopus and wos offerings both restricted to publications present on those platforms. however, these services can share data between them.

researchers

pids for organizations

ROR

GRID

ISNE

there are good odds you'll never need to know what the ror id for unb is. the predominant use-case for organizational ids is in strengthening connections between records using open scholarly infrastructure.

organizations

a quick example re: ror

we write UNB as:

- UNB

- University of New Brunswick

- UNBF / UNBSJ

- UNB Fredericton

- University of New Brunswick Saint John

registration agencies

registration agencies provide metadata schema through which users can describe the objects they are registering pids for.

as you can imagine, you'd describe a person differently than you'd describe a dataset, or a journal article, or an organization. even when agencies use the same type of pid (like the doi), the schema they use may vary.

for example

let's look the registered metadata for a doi: 10.4324/9780203051238-5

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<crossref_result version="3.0" xsi:schemaLocation="http://www.crossref.org/qrschema/3.0 http://www.crossref.org/schemas/crossref_query_output3.0.xsd">

<query_result>

<head>

<doi_batch_id>none</doi_batch_id>

</head>

<body>

<query status="resolved">

<doi type="book_content">10.4324/9780203051238-5</doi>

<crm-item name="publisher-name" type="string">Informa UK Limited</crm-item>

<crm-item name="prefix-name" type="string">Informa UK (Routledge)</crm-item>

<crm-item name="member-id" type="number">301</crm-item>

<crm-item name="citation-id" type="number">122425695</crm-item>

<crm-item name="book-id" type="number">1477192</crm-item>

<crm-item name="deposit-timestamp" type="number">2020122110554080199</crm-item>

<crm-item name="owner-prefix" type="string">10.4324</crm-item>

<crm-item name="last-update" type="date">2020-12-21T15:07:00Z</crm-item>

<crm-item name="created" type="date">2020-12-21T15:06:59Z</crm-item>

<crm-item name="citedby-count" type="number">0</crm-item>

<doi_record>

<crossref xsi:schemaLocation="http://www.crossref.org/xschema/1.1 http://doi.crossref.org/schemas/unixref1.1.xsd">

<book book_type="other">

<book_metadata language="en">

<contributors>

<person_name sequence="first" contributor_role="author">

<given_name>Richard</given_name>

<surname>Smiraglia</surname>

</person_name>

</contributors>

<titles>

<title>Metadata</title>

<subtitle>A Cataloger's Primer</subtitle>

</titles>

<edition_number>0</edition_number>

<publication_date media_type="online">

<month>11</month>

<day>12</day>

<year>2012</year>

</publication_date>

<isbn media_type="electronic">9780203051238</isbn>

<publisher>

<publisher_name>Routledge</publisher_name>

</publisher>

<doi_data>

<doi>10.4324/9780203051238</doi>

<timestamp>2020122110554078499</timestamp>

<resource>https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/9781136435843</resource>

</doi_data>

</book_metadata>

<content_item component_type="chapter" publication_type="full_text" language="en">

<titles>

<title>Understanding Metadata and Metadata Schemes</title>

</titles>

<publication_date>

<year>2012</year>

<month>11</month>

<day>12</day>

</publication_date>

<pages>

<first_page>25</first_page>

<last_page>44</last_page>

</pages>

<doi_data>

<doi>10.4324/9780203051238-5</doi>

<timestamp>2020122110554080199</timestamp>

<resource>https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/9781136435843/chapters/10.4324/9780203051238-5</resource>

</doi_data>

</content_item>

</book>

</crossref>

</doi_record>

</query>

</body>

</query_result>

</crossref_result>i'm sorry to do this to you.

there's a lot of information here:

publisher

deposit and update timestamp

book type

contributors (first, role=author)

title and subtitle

publication date

doi for the book

link for the book

chapter title

doi for the chapter

link for the chapter

<doi_data>

<doi>10.4324/9780203051238</doi>

<timestamp>2020122110554078499</timestamp>

<resource>https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/9781136435843</resource>

</doi_data>

</book_metadata>

<content_item component_type="chapter" publication_type="full_text" language="en">

<titles>

<title>Understanding Metadata and Metadata Schemes</title>

</titles>

<publication_date>

<year>2012</year>

<month>11</month>

<day>12</day>

</publication_date>

<pages>

<first_page>25</first_page>

<last_page>44</last_page>

</pages>

<doi_data>

<doi>10.4324/9780203051238-5</doi>

<timestamp>2020122110554080199</timestamp>

<resource>https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/9781136435843/chapters/10.4324/9780203051238-5</resource>

</doi_data>

<!-- urls are part of the metadata of a doi. -->

<!-- when you change the location of content, you update your doi with the new location. everyone who uses the doi gets to the content no matter where you put it, so long as that doi is updated. this means, the doi is persistent.-->metadata is hugely useful

unlike publications themselves, metadata is typically free. and, we can learn a lot from it. crossref, for example, can store the following things as publicly accessible metadata:

title

subtitle

authors

orcids

affiliation

copyright license

funder/grant ids

languages

ror

references

resource location

version

publisher

journal

volume/issue

related dois

dates

abstracts

crossref makes this metadata available through a public api.

is it time for you to tell me what an API is?

what an api is

api stands for

Application Programming Interface

an API is, basically, a set of rules for interacting with software

think of it as being a little like a translator working as an intermediary between two people who don't speak the same language

what an api is

APIs are everywhere. when my calendar app tells me today's forecast, it's accessing that information using the Accuweather API. when my watch vibrates because i got a text message, that's because Garmin's API is communicating with Apple's notifications API.

APIs are how disparate systems, built by different people, using different languages and definitions, find common ground and share information.

this is open scholarly infrastructure

this network of APIs is like a municipal water system (get it?). it is, increasingly, infrastructure relied upon by researchers and institutions whether or not they are really aware of it.

almost all open scholarly infrastructure is based around APIs.

open scholarly infrastructure

what open scholarly infrastructure is

open scholarly infrastructure is a network of scholarly-research-focused open-source platforms, service providers, and APIs that work in concert to share data, illuminate relationships, and make research more discoverable.

https://openscholarlyinfrastructure.org/

open scholarly infrastructure is best described through examples.

example one // orcid

i am setting up my orcid account

let's pretend

example one // orcid

within orcid, i can check against the crossref and datacite APIs for any publications matching my name.

i want to add my publications!

example one // orcid

it will take me a while to do this the first time, and it’ll only work if my articles have dois.

most publications register dois

example one // orcid

for all my publications I know are mine (and have dois) the metadata is automatically pulled into my orcid account.

orcid pulls that metadata from the crossref API.

but...

example one // orcid

now that I have an orcid, that metadata (ideally) is included in the doi when I publish.

crossref will say to orcid, "we know this work belongs to this scholar, because their orcid is in the metadata. we'll just push this new publication to their record automatically."

and...!

example two // unpaywall

but, i use this browser extension called unpaywall.

the unpaywall plugin will tell me if an article i'm looking for has an open access version i don't know about.

i'm looking for an article i need, but the library doesn't have a subscription.

example two // unpaywall

because unpaywall indexes metadata crawled from open institutional or disciplinary repositories world wide and compares that metadata against datacite and crossref APIs, it can show me an open access version of a work if it exists.

this might be a preprint or an accepted manuscript. it might not be the same as the final version, but it's definitely a version i now have access to.

unpaywall uses the doi for the article i'm looking at and...

example three // funders and orcid

i've applied for funding from an agency that has an orcid account or integration.

let’s pretend…

example three // funders and orcid

funding id

grant id

datasets

articles

that agency can push new data to my orcid account.

example three // funders and orcid

the next time I apply for funding, i just push my orcid to the agency and they can pull my works without me filling out the same form again.

and ideally...

open scholarly infrastructure ties the room together

the water supply

open scholarly infrastructure

without the crossref API, all of these examples kind of fall apart.

publications that aren’t using dois are, essentially, “off the grid.”

the absence of these connections results in a lot of folks entering the same metadata into systems, over and over, by hand. Or hiring graduate students to do this for them.

that's an excellent use of everyone's time, definitely.

persistent identifiers

in concert with open scholarly infrastructure, pids allow us to see the big picture through these connections and interactions. it can expose relationships between data and research or institutions and outcomes. it can make research outcomes more discoverable.

when we talk about pids, we’re talking about supporting open infrastructure and free exchange of metadata.

a word on metadata

the metadata we get out of these systems, and its utility, is very much dependent on its quality.

we have a general expression in the metadata universe. that's "garbage in, garbage out."

metadata is kind of everyone's responsibility. researchers, librarians, publishers, registration agencies... everyone has a stake in accurate, usable metadata.

metadata is a very complicated topic i could talk about for twice the length of this talk. any time! let me know! i'll do it.

i understand that this is a lot.

what i'm hoping you'll come away with today is a little perspective.

pids aren't

- just links to things

- academic bit.ly

- status symbols

- permanent

- magic

pids are

- potentially huge time savers

- useful for finding research

- interconnected between services

- the backbone of open scholarly infrastructure

thanks for listening to this bit!

i sure hope that it was coherent.

we're gonna take a break

we'll reconvene at 12:15

part ii

part ii

12:15-12:45

overview of the services and features of ORCID, including information on signing up for the service and adding your publications/works to your profile.

agenda

- what is orcid profile?

- what are the benefits to orcid?

- what are the concerns with orcid?

- live demo of orcid.

what is an orcid profile?

what an orcid profile is

an orcid profile is basically an online, academic cv

users can fill out their information for:

- employment

- education/qualifications

- invited positions/distinctions

- membership/service

- funding

- works

they can control what is public or private

what an orcid profile is

orcid profiles are free for anyone to get

you don't need to be affiliated with an institution

they are ideal for scholars who move between institutions because they have full control over what is in the profile, and who can access it.

what an orcid profile is

sharing your orcid id will allow someone to see everything you've set to public

when you publish with an orcid id, it will be displayed along with your name and affiliation so anyone interested can view your public profile

what an orcid profile is

also because your orcid id is stored as metadata within a doi, crossref or datacite can push publication metadata to your orcid profile when you publish

within your profile settings, you can set datacite and crossref as trusted parties. this way, so long as you publish somewhere that uses dois, you will not have to manually enter your publications into your profile

what an orcid profile is

you can also share metadata and publications between scopus id/researcher id and orcid.

you can use your orcid id to populate them, or vice versa

within your profile settings, you can set scopus id/researcher id as trusted parties.

what an orcid profile is

it is possible to share your publication record using your orcid profile instead of submitting a long list of citations

this is increasingly common, and supported (if not required) by a number of funders worldwide

none of those funders are canadian (yet)

this sounds pretty good

it is

this is the basic sales pitch to researchers, i think

a not-for-profit profile service that serves as a portable academic cv that allows for some automation of metadata entry

and

is increasingly used for grant applications or other administrative time savings

it is easy to recommend and easy to use

signing up is astoundingly simple

metadata entry and correction, as always, takes a non-trivial amount of time

scholars have control, and can dictate access to/from trusted parties

what is a trusted party?

who has access to what?

what a trusted party is

to talk about this, we need to talk about APIs again.

as you may recall from part i, an API (application programming interface) is, basically, a set of rules for interacting with software

think of it as being a little like a translator working as an intermediary between two people who don't speak the same language

what a trusted party is

orcid has two apis

it has a public api, which is open. you can write software that pulls metadata from the public api. but it only exposes public metadata from a profile.

it also has a member api, which is closed and restricted to organizations who are orcid members. (we are an orcid member)

what a trusted party is

a trusted party is an organization who has been authorized by orcid to:

- read private metadata as well as public

- write metadata to a profile on the researcher's behalf

but, the researcher has to individually allow a trusted party. the researcher has full control over external access via the member api. the process requires consent.

what a trusted party is

these trusted party interactions; where an organization can leverage the member api for publishing metadata and private details (assuming the researcher says "yes"), are very often referred to as integrations

do we have one of those?

not at the moment, no

please tell me this can help with my ccv.

what about ccv?

the ccv (canadian common cv) has no integrations with anyone. it doesn't have an open api at all, and is not actively developed.

it is possible to get publication metadata from orcid to ccv. i wrote a guide for that.

ccv ingests bibtex, which you might recall was the prominent citation schema of endnote. it's also the way metadata is stored in orcid.

what about ccv?

the tri-agency is currently looking into the successor for ccv.

you can read more about that project here.

we can assume it will support orcid ingest, but we absolutely do not know that for sure.

why should i care about orcid?

well, orcid is useful for:

- personally tracking publication history and name disambiguation for our scholars

- submitting citation information to member organizations that are trusted parties (funding bodies in the US or the UK in particular)

- a portable cv that some schools in Canada can use instead of a word document for assessment/annual review (those with a significant investment in their CRIS systems)

- tracking information that scopus- and researcher-id do not track (they are journal-specific)

orcid is useful for:

being a modern researcher interested in saving yourself some drudgery.

it is best described as an investment. it will take time and effort to fully set one up, but ideally, in the not-too-distant future, its ubiquity will extend to canadian researchers.

the bottom line

for researchers, interest in orcid may vary from discipline-to-discipline, career-to-career

some are very on-board and into it. some could care less. some folks are concerned that it's a little like being barcoded.

the bottom line

ultimately, it is worth noting that even if UNB did use a platform that supported ORCID (and right now, they do not), each researcher would have to decide whether or not to make UNB a trusted party that could see private information.

let's pop over to orcid.org and take a tour

thanks, by the way