An introduction to Kotlin type system

An introduction to Kotlin type system

and more

Kotlin is a ..., statically typed,

..., programming language.

-wikipediaKotlin is a ..., statically typed,

..., programming language.

What is a type?

What is a type?

What is a type?

What is a class?

What is a type?

What is a class?

What is an object?

Object vs Class

Object vs Class

Class is a blueprint or template from which objects are created.

Object is an instance of a class.

Object vs Class

Class is a blueprint or template from which objects are created.

Object is an instance of a class.

class A

Object vs Class

Class is a blueprint or template from which objects are created.

Object is an instance of a class.

class A

val x = A()Class vs Type

A type summarizes the common features of a set of objects with the same characteristics. We may say that a type is an abstract interface that specifies how an object can be used.

Class vs Type

A type summarizes the common features of a set of objects with the same characteristics. We may say that a type is an abstract interface that specifies how an object can be used.

A class represents an implementation of the type. It is a concrete data structure and collection of methods.

A data type (or simply type) is a collection or grouping of data values, usually specified by a set of possible values, a set of allowed operations on these values, ... A data type specification in a program constrains the possible values that an expression, such as a variable or a function call, might take.

-wikipediaWe can define our types by defining classes, interfaces, Enums, ...

Every classifier, i.e. classes and interfaces, generates a set of types.

Every classifier, i.e. classes and interfaces, generates a set of types. In most cases, it generates a single type, but an example where a single class generates multiple types is a generic class:

Every classifier, i.e. classes and interfaces, generates a set of types. In most cases, it generates a single type, but an example where a single class generates multiple types is a generic class:

class Box<T>

We can say that in the above snippet we see definition of class A, but the type of x is A. Therefore A is both a name of the class and of the type. The class is a template for an object but concrete object have a type. Actually, every expression has a type!

class A

val x = A()We can say that in the above snippet we see definition of class A, but the type of x is A. Therefore A is both a name of the class and of the type. The class is a template for an object but concrete object have a type. Actually, every expression has a type!

class A

val x = A()Statement vs Expression

Statement vs Expression

An expression in a programming language is a combination of one or more explicit values, constants, variables, operators and functions that the programming language interprets and computes to produce another value.

An expression has a value, which can be used as part of another expression.

Statement vs Expression

In computer programming, a statement is the smallest standalone element of an imperative programming language that expresses some action to be carried out.

Java type system

Java type system

Object

Java type system

Object

Number

MyClass

String

Java type system

Object

Number

MyClass

String

Integer

MySubClass

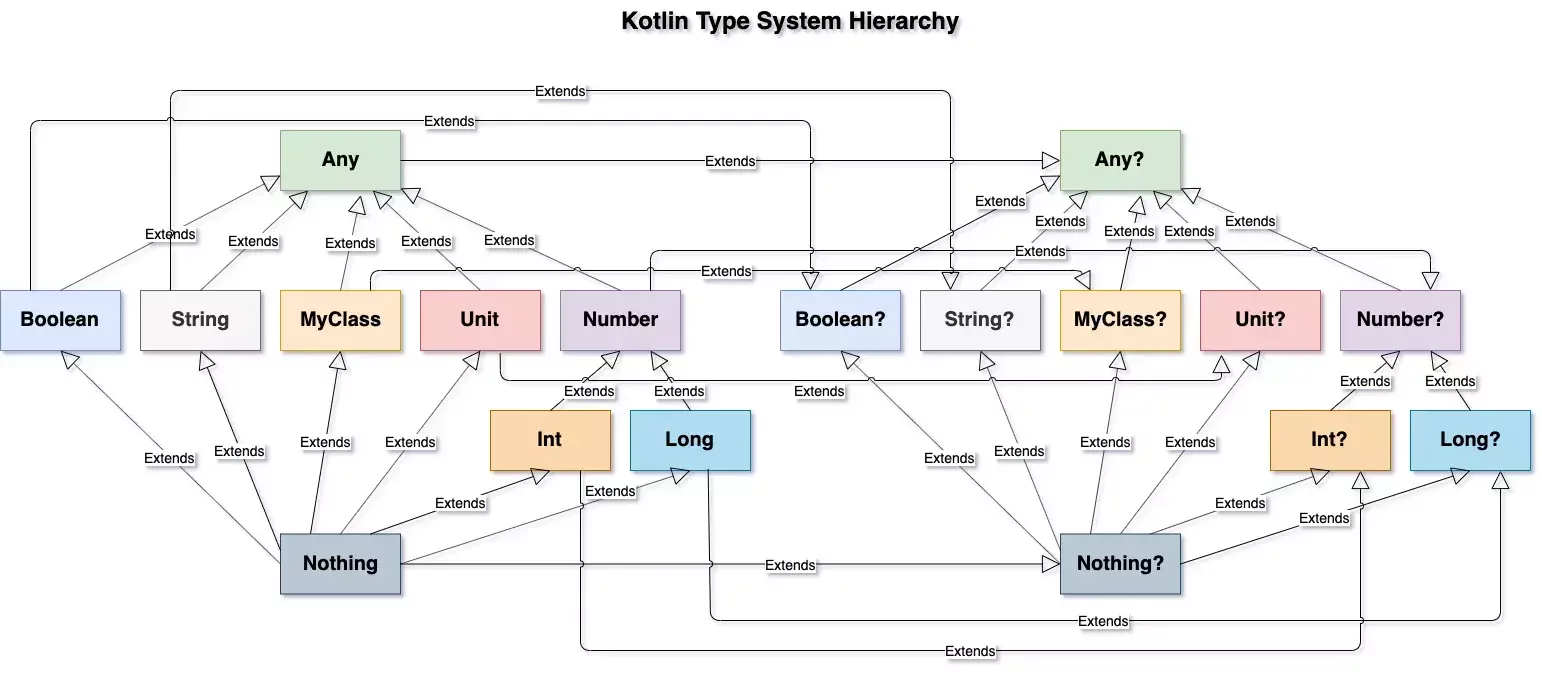

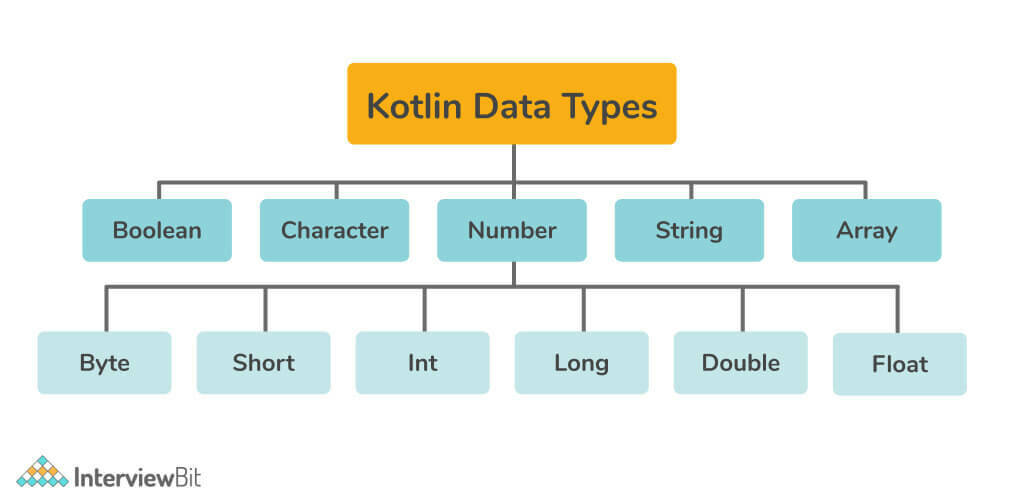

Kotlin type system

Any

Kotlin type system

Any

Number

MyClass

String

Kotlin type system

Any

Number

MyClass

String

Int

MySubClass

Kotlin type system

Any

Number

MyClass

String

Int

MySubClass

Nothing

Kotlin type system

Any

Number

MyClass

String

Int

MySubClass

Nothing

Object

=

Kotlin type system

Any

Number

MyClass

String

Int

MySubClass

Nothing

Object

=

?

Kotlin type system

Any

Number

MyClass

String

Int

MySubClass

Nothing

Object

=

?

Object test = nullKotlin type system

Any

Number

MyClass

String

Int

MySubClass

Nothing

Object

=

?

Object test = nullval test: Any = nullKotlin type system

Any

Number

MyClass

String

Int

MySubClass

Nothing

Any?

subtyping by

Nullablitiy

Kotlin type system

Any

Number

MyClass

String

Int

MySubClass

Nothing

Any?

Number?

MyClass?

String?

Int?

MySubClass?

Nothing?

Kotlin type system

Kotlin type system

When we define a class

class MyClass

We automatically have 2 types available

Kotlin type system

When we define a class

class MyClass

We automatically have 2 types available

val a: MyClass

val b: MyClass?

Kotlin type system

A type without a question mark denotes that variables of this type can’t store null references. This means all regular types are non-nullable by default, unless explicitly marked as nullable.

Kotlin type system

Once you have a value of nullable type, the set of operations you can perform on it is restricted. For example, you can no longer call methods on it. The compiler will now complain about the call to length in the function body:

fun main() {

val x: String? = null

var y: String = x

// ERROR: Type mismatch:

// inferred type is String? but String was expected

}

Kotlin type system

fun strLen(s: String?) = s.lengthKotlin type system

fun strLen(s: String?) = s.lengthError: Only safe (?.) or non-null asserted (!!.) calls are allowed on a nullable receiver of type String?

Kotlin type system

fun strLenSafe(s: String?): Int =

if (s != null) s.length else 0Kotlin type system

fun strLenSafe(s: String?): Int =

if (s != null) s.length else 0Once you perform the comparison, the compiler remembers that and treats the value as non-nullable in the scope where the check has been performed.

Kotlin type system

Note: At runtime, objects of nullable types and objects of non-nullable types are treated the same: A nullable type isn't a wrapper for a non-nullable type. All checks are performed at compile time. That means there's almost no runtime overhead for working with nullable types in Kotlin.

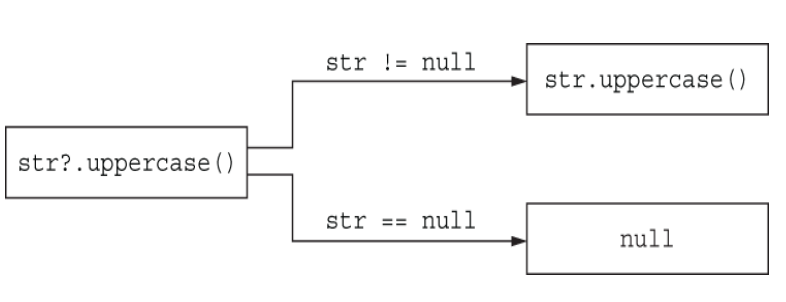

Kotlin type system

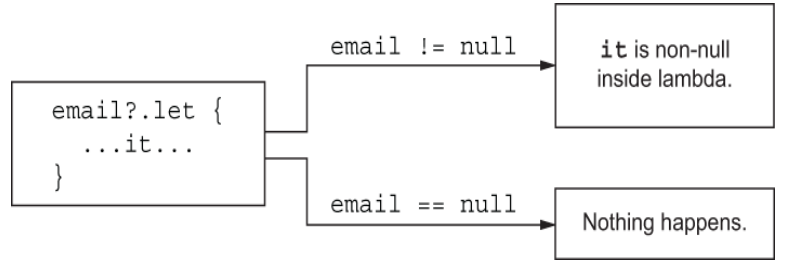

safe-call operator

Kotlin type system

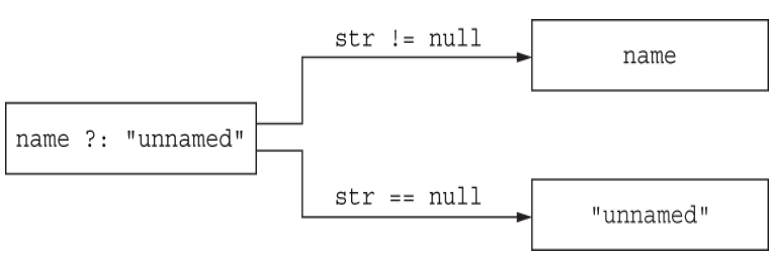

Elvis operator

val x =

Kotlin type system

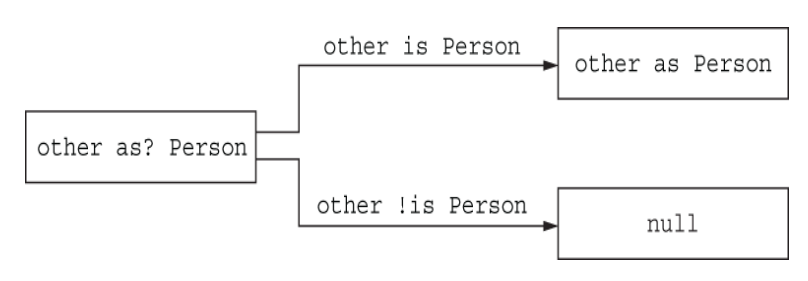

safe-cast operator

Kotlin type system

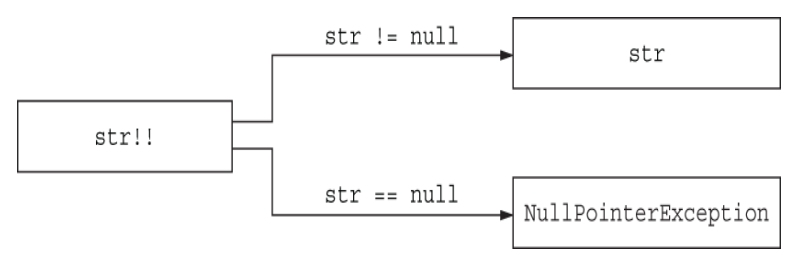

non-null assertion operator

Kotlin type system

Kotlin type system

Kotlin type system

kotlin.Any

Kotlin type system

Besides being the unified supertype of all non-nullable types, kotlin.Any must also provide the following methods.

kotlin.Any

Kotlin type system

Besides being the unified supertype of all non-nullable types, kotlin.Any must also provide the following methods.

public open operator fun equals(other: Any?): Booleanpublic open fun hashCode(): Intpublic open fun toString(): Stringkotlin.Any

Kotlin type system

kotlin.Nothing

Kotlin type system

kotlin.Nothing is an uninhabited type, which means the evaluation of an expression with kotlin.Nothing type can never complete normally. Therefore, it is used to mark special situations, such as

- non-terminating expressions

- exceptional control flow

- control flow transfer

kotlin.Nothing

Kotlin type system

kotlin.Nothing

fun fail(message: String): Nothing {

throw IllegalStateException(message)

}

val address = company.address ?: fail("No address")

println(address.city)Kotlin type system

kotlin.Unit is a unit type, i.e., a type with only one value; all values of type kotlin.Unit should reference the same underlying kotlin.Unit object. It is somewhat similar in purpose to void return type in other programming languages in that it signifies an absence of a value (i.e. the returned type for a function returning nothing), but is different in that there is, in fact, a single value of this type.

kotlin.Unit

Kotlin type system

kotlin.Unit

public object Unit {

override fun toString() = "kotlin.Unit"

}Kotlin type system

Where is null on the hierarchy?

When we declare a property without explicitly indicate its type and assigning null as its value, its type will be determined as Nothing? that’s because this is the data type of null. Null is the only possible instance of Nothing?, there is not an object which type is specifically Nothing?

Kotlin type system

Where is null on the hierarchy?

At code level we can be totally sure that when we see a property which type is Nothing? the only possible value it can keep is null. Also, since Nothing is the subtype of all types, null can be used as the nullable version of any type we declare.

Kotlin type system

Where is null on the hierarchy?

fun print(value: Any?) = println(

when (value) {

is String -> "value is string"

is Int -> "value is int"

else -> "value unknown"

}

)Kotlin type system

Where is null on the hierarchy?

fun print(value: Any?) = println(

when (value) {

is String -> "value is string"

is Int -> "value is int"

is null -> "value is null"

else -> "value unknown"

}

)Kotlin type system

Where is null on the hierarchy?

fun print(value: Any?) = println(

when (value) {

is String -> "value is string"

is Int -> "value is int"

is null -> "value is null"

else -> "value unknown"

}

)error: type expected

Kotlin type system

Where is null on the hierarchy?

fun print(value: Any?) = println(

when (value) {

is String -> "value is string"

is Int -> "value is int"

is Nothing? -> "value is null"

else -> "value unknown"

}

)Kotlin type system

Generic types are, by default, nullable

fun <T> printer(value: T) {

print("Printing the value: "+ value)

}

printer("Hola")

printer(1)

printer(1.1)

printer(null)Kotlin type system

Generic types are, by default, nullable

If we don’t want to allow null values we need to modify our example as below:

fun <T: Any> printer(value: T) {

print("Printing the value: "+ value)

}data class User (

val firstName: String?,

val lastName: String?

)

fun hasValidData(user: User): Boolean{

val firstName = user.firstName ?: return false

val lastName = user.lastName ?: return false

return firstName.isNotBlank() && lastName.isNotBlank()

}Kotlin type system

data class User (

val firstName: String?,

val lastName: String?

)

fun hasValidData(user: User): Boolean{

val firstName = user.firstName ?: return false

val lastName = user.lastName ?: return false

return firstName.isNotBlank() && lastName.isNotBlank()

}What is the inferred type?

Kotlin type system

data class User (

val firstName: String?,

val lastName: String?

)

fun hasValidData(user: User): Boolean{

val firstName: String = user.firstName ?: return false

val lastName = user.lastName ?: return false

return firstName.isNotBlank() && lastName.isNotBlank()

}What is the inferred type?

Kotlin type system

data class User (

val firstName: String?,

val lastName: String?

)

fun hasValidData(user: User): Boolean{

val firstName: String = user.firstName ?: return false

val lastName = user.lastName ?: return false

return firstName.isNotBlank() && lastName.isNotBlank()

}Why is it possible to assign return to a varialbe?

Kotlin type system

In Kotlin almost everything is an expression.

val name = when (number) {

1 -> "one"

2 -> "two"

}Kotlin type system

In Kotlin almost everything is an expression.

val name = when (number) {

1 -> "one"

2 -> "two"

}val message = if (number % 2) "even" else "odd"Kotlin type system

In Kotlin almost everything is an expression.

val function = fun (param: String){

//do stuff

}val name = when (number) {

1 -> "one"

2 -> "two"

}val message = if (number % 2) "even" else "odd"Kotlin type system

data class User (

val firstName: String?,

val lastName: String?

)

fun hasValidData(user: User): Boolean{

val firstName: String = user.firstName ?: return false

val lastName = user.lastName ?: return false

return firstName.isNotBlank() && lastName.isNotBlank()

}Why is it possible to assign return to a varialbe?

Kotlin type system

data class User (

val firstName: String?,

val lastName: String?

)

fun hasValidData(user: User): Boolean{

val firstName: String = user.firstName ?: return false

val lastName = user.lastName ?: return false

return firstName.isNotBlank() && lastName.isNotBlank()

}Kotlin type system

returns Nothing

Why is it possible to assign return to a varialbe?

data class User (

val firstName: String?,

val lastName: String?

)

fun hasValidData(user: User): Boolean{

val firstName: String = user.firstName ?: return false

val lastName = user.lastName ?: return false

return firstName.isNotBlank() && lastName.isNotBlank()

}Because Nothing is subtype of everything

Kotlin type system

Liskov Substitution Principle

If S is subtype of T, then objects of type T may be replaced with objects of type S without altering any of the desirable properties of that program.

data class User (

val firstName: String?,

val lastName: String?

)

fun hasValidData(user: User): Boolean{

val firstName: String = return false

val lastName = user.lastName ?: return false

return firstName.isNotBlank() && lastName.isNotBlank()

}Kotlin type system

data class User (

val firstName: String?,

val lastName: String?

)

fun hasValidData(user: User): Boolean{

val firstName: String = return false

val lastName = user.lastName ?: return false

return firstName.isNotBlank() && lastName.isNotBlank()

}possible but useless

Kotlin type system

data class User (

val firstName: String?,

val lastName: String?

)

fun hasValidData(user: User): Boolean{

val firstName: String = return false

val lastName = user.lastName ?: return false

return firstName.isNotBlank() && lastName.isNotBlank()

}possible but useless

Kotlin type system

Warning: Unreachable code

data class User (

val firstName: String?,

val lastName: String?

)

fun hasValidData(user: User): Boolean{

val firstName = user.firstName ?: throw RunTimeException()

val lastName = user.lastName ?: return false

return firstName.isNotBlank() && lastName.isNotBlank()

}Throw returns Nothing too.

Kotlin type system

fun test(): String?{

TODO()

return null

}Warning: Unreachable code

public inline fun TODO(): Nothing = throw NotImplementedError()Kotlin type system

fun test(): String?{

TODO()

return null

}Warning: Unreachable code

The compiler knows after Nothing is returned, the execution flow stops.

public inline fun TODO(): Nothing = throw NotImplementedError()Kotlin type system

So this will actually never be assigned,

because the function ends with the return statement.

data class User (

val firstName: String?,

val lastName: String?

)

fun hasValidData(user: User): Boolean{

val firstName: String = user.firstName ?: return false

val lastName = user.lastName ?: return false

return firstName.isNotBlank() && lastName.isNotBlank()

}Kotlin type system

Kotlin vs Java

Kotlin value assignment (a = 1) is not an expression in Kotlin, while it is in Java because over there it returns assigned value (in Java you can do

a = b = 2

or

a = 2 * (b = 3))

Kotlin vs Java

This helps avoid confusion between comparisons and assignments, which is a common source of mistakes in languages that treat them as expressions, such as Java or C/C++.

Kotlin vs Java

All usages of control structures (if, switch) in Java are not expressions, while Kotlin allowed if, when and try to return values:

val bigger = if(a > b) a else b

val color = when {

relax -> GREEN

studyTime -> YELLOW

else -> BLUE

}

val object = try {

gson.fromJson(json)

} catch (e: Throwable) {

null

}Kotlin vs Java

Kotlin vs Java

In java primitive types aren’t part of the hierarchy.

Kotlin vs Java

In java primitive types aren’t part of the hierarchy.

That means you have to use wrapper types such as java.lang.Integer to represent a primitive type value when Object is required. In Kotlin, Any is a supertype of all types, including the primitive types such as Int.

Kotlin vs Java

All Kotlin classes have the following three methods: toString, equals, and hashCode. These methods are inherited from Any. Other methods defined on java.lang.Object (such as wait and notify) aren’t available on Any, but you can call them if you manually cast the value to java.lang.Object.

Kotlin vs Java

What distinguishes Kotlin’s Unit from Java’s void? Unit is a full-fledged type, and, unlike void, it can be used as a type argument. Only one value of this type exists; it’s also called Unit and is returned implicitly.

Kotlin vs Java

This is useful when you override a function that returns a generic parameter and make it return a value of the Unit type.

Kotlin vs Java

This is useful when you override a function that returns a generic parameter and make it return a value of the Unit type.

interface Processor{

fun process(): T

}

class NoResultProcessor: Processor{

override fun process(){

// do stuff

}

}Kotlin vs Java

Kotlin doesn’t automatically convert numbers from one type to another, even when the type you’re assigning your value to is larger and could comfortably hold the value you’re trying to assign.

Kotlin vs Java

Kotlin doesn’t automatically convert numbers from one type to another, even when the type you’re assigning your value to is larger and could comfortably hold the value you’re trying to assign.

byte b = 4;

short s = b;

int x = s;

long l = x;

float f = l;

double y = f;Kotlin vs Java

Kotlin doesn’t automatically convert numbers from one type to another, even when the type you’re assigning your value to is larger and could comfortably hold the value you’re trying to assign.

byte b = 4;

short s = b;

int x = s;

long l = x;

float f = l;

double y = f;val i = 1

val l: Long = i // Error: type mismatchInteger type widening

Kotlin vs Java

Integer type widening

fun foo(value: Int) = 1

fun foo(value: Short) = 2Kotlin vs Java

Integer type widening

fun foo(value: Int) = 1

fun foo(value: Short) = 2foo(2)Kotlin vs Java

What I did not cover:

- Platform types

- Covariance and contravariance

- Unsigned number types

Kotlin vs Java

What I did not cover:

- Platform types

- Covariance and contravariance

- Unsigned number types

- Union types with errors

Kotlin vs Java

https://www.linkedin.com/in/ali-ahmadabadiha-59690923b/

resources

covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

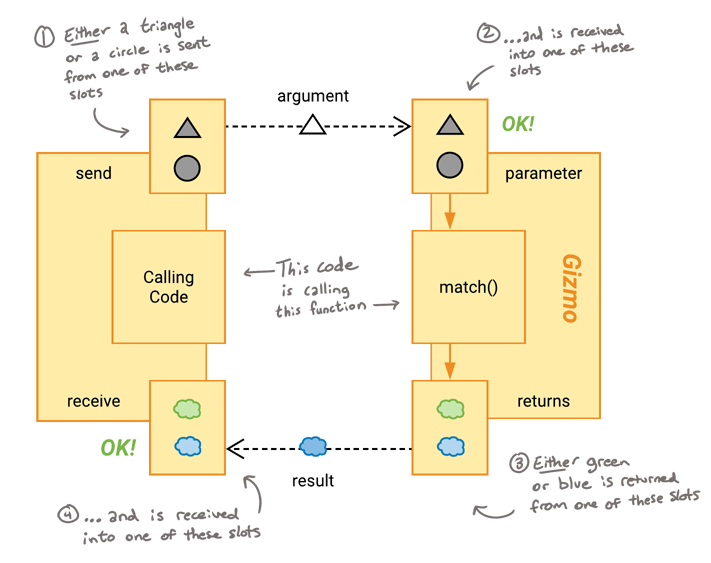

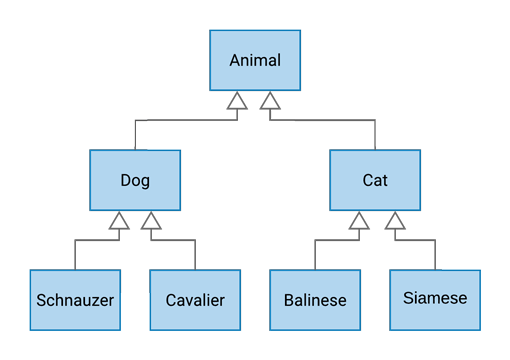

When it comes to generics, what trips us up the most? Subtyping.

covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

Variance describes the relationship between parameterized classes.

Variance tells us about the relationship between C<Dog> and C<Animal> where Dog is a subtype of Animal.

covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

Sure, we know intuitively that a Dog is a subtype of an Animal. But it’s easy to get confused about why an Array<Dog> isn’t a subtype of an Array<Animal>.

public class Array<T>covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

By default, generics in Kotlin (and Java) are invariant.

covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

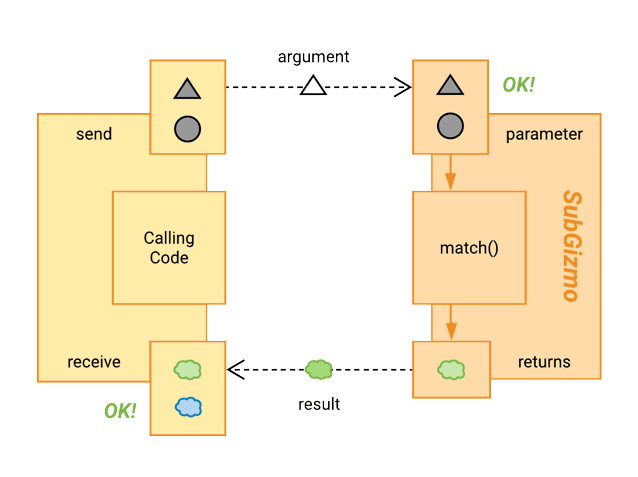

In order for a subtype to truly be a subtype, you must be able to swap one in as a replacement for its supertype, and the rest of the code shouldn’t notice anything different.

covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

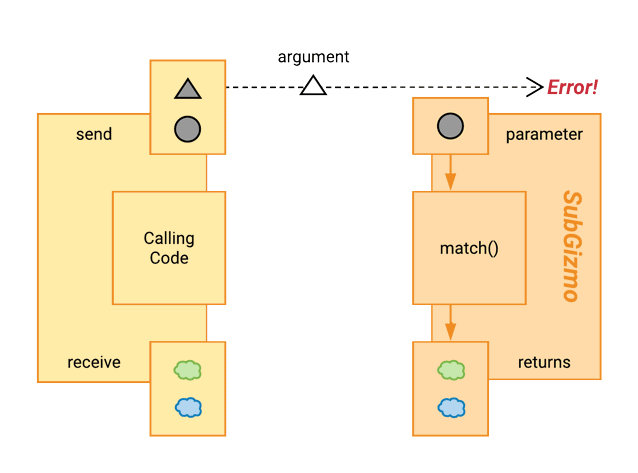

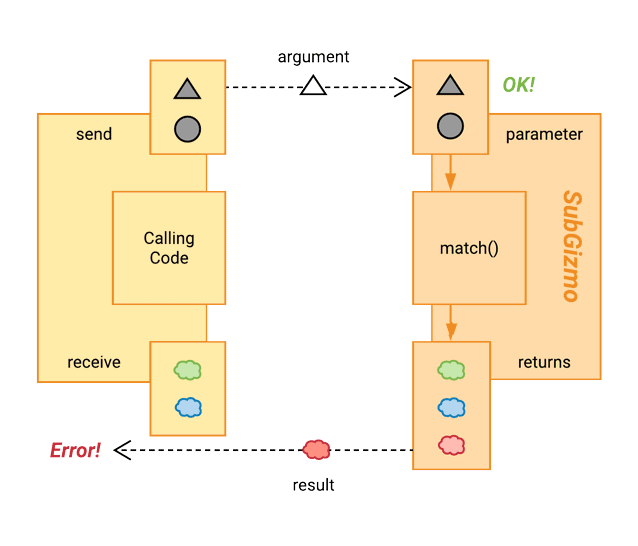

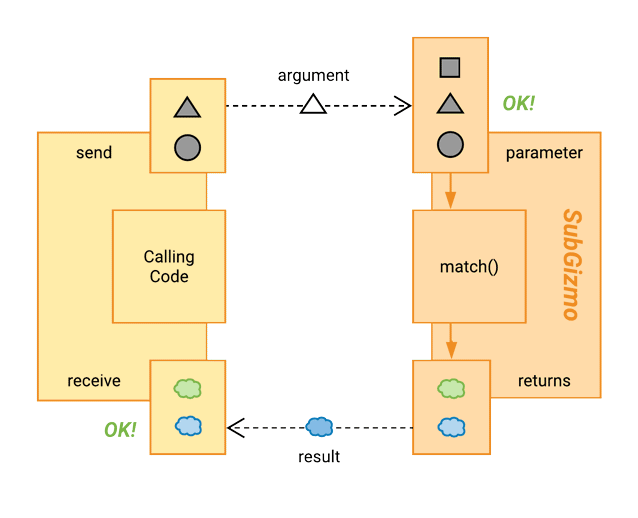

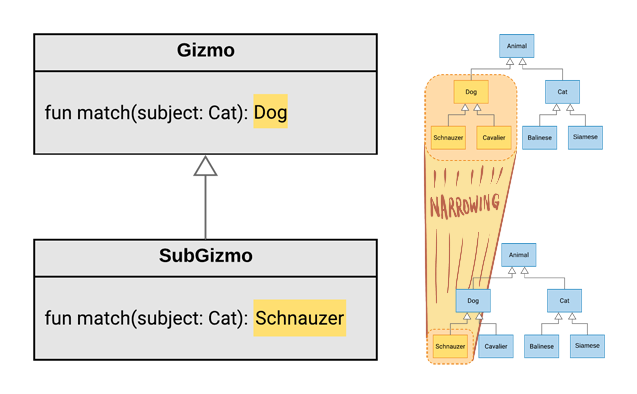

Now, this calling code has been using Gizmo successfully for a long, long time. But today, we’re going to secretly switch out Gizmo with our new SubGizmo (which, of course, is a subtype of Gizmo!).

covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

Narrowing Arguments

covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

Expanding Returns

covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

- A subtype must accept all argument types that its supertype does.

- A subtype must NOT return a result type that its supertype wouldn’t return.

covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

- A subtype must accept all argument types that its supertype does.

- A subtype must NOT return a result type that its supertype wouldn’t return.

covariance and contravariance

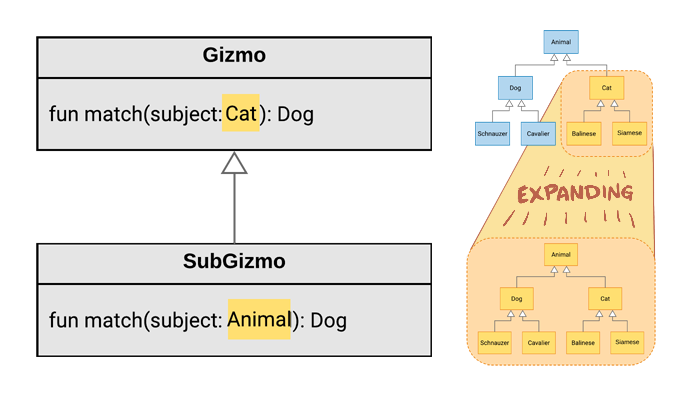

in Kotlin

Expanding Arguments

covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

Narrowing Returns

covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

- A subtype must accept at least the same range of types as its supertype declares.

- A subtype must return at most the same range of types as its supertype declares

covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

- A subtype must accept at least the same range of types as its supertype declares.

- A subtype must return at most the same range of types as its supertype declares

These two rules form the basis of variance.

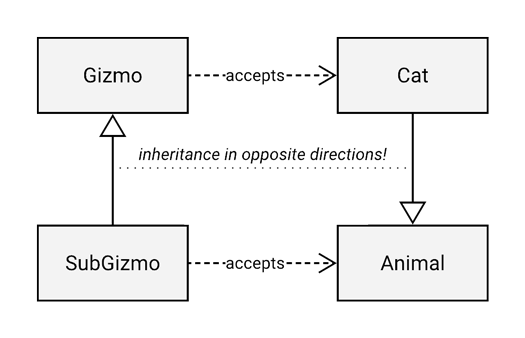

covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

Accepting Arguments - Contravariance

covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

Accepting Arguments - Contravariance

covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

Even though this is safe for programming languages to do, Kotlin has followed Java’s lead, and does not allow for contravariance on argument types in normal class and interface inheritance, in order to allow for method overloading.

covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

Even though this is safe for programming languages to do, Kotlin has followed Java’s lead, and does not allow for contravariance on argument types in normal class and interface inheritance, in order to allow for method overloading.

But we have a workaround for this in kotlin.

covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

If you want contravariant argument types with inheritance, then instead of using a function, you can use a property. For example:

open class Super {

open val execute: (B) -> Unit = {

// ...

}

}

class Sub : Super() {

override val execute: (A) -> Unit = {

// ...

}

}covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

Returning Results - Covariance

covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

Returning Results - Covariance

covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

Returning Results - Covariance

Kotlin does allow for covariant return types in normal class and interface inheritance:

interface Gizmo {

fun match(subject: Cat): Dog

}

interface SubGizmo : Gizmo {

override fun match(subject: Cat): Schnauzer

}covariance and contravariance

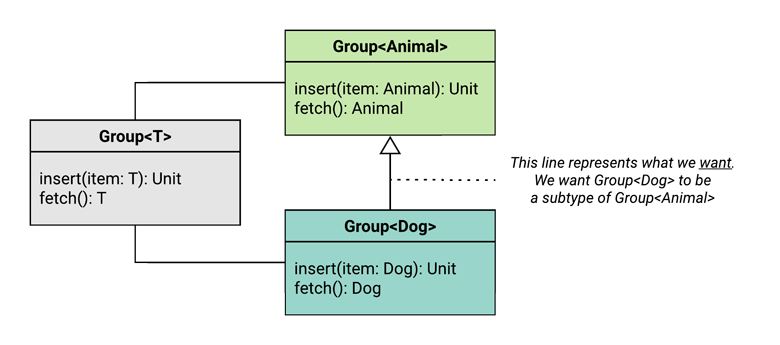

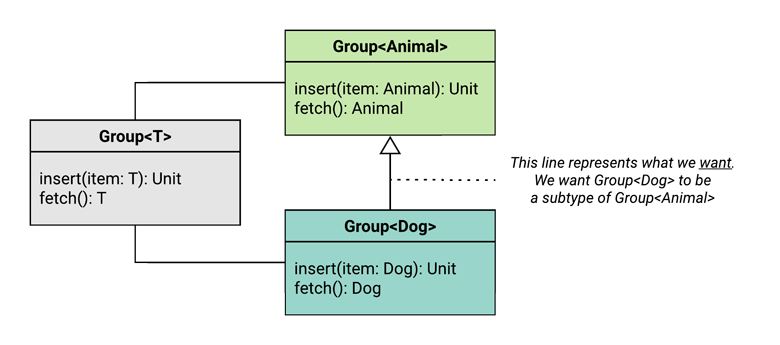

in Kotlin

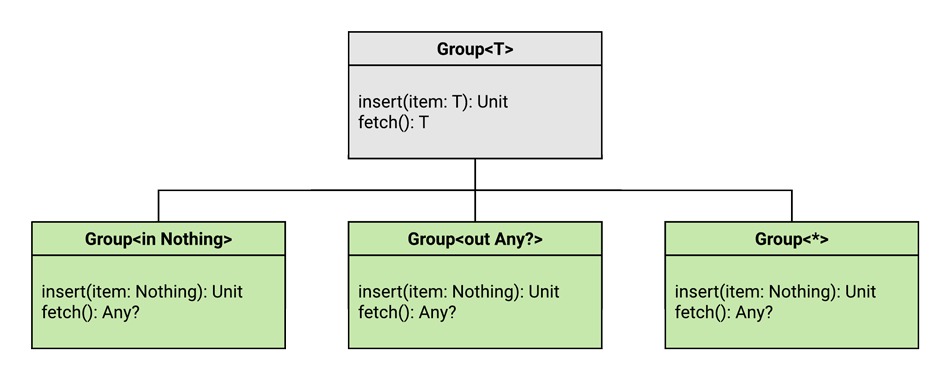

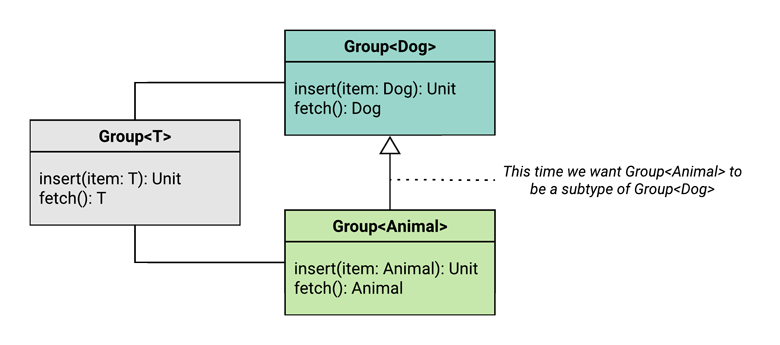

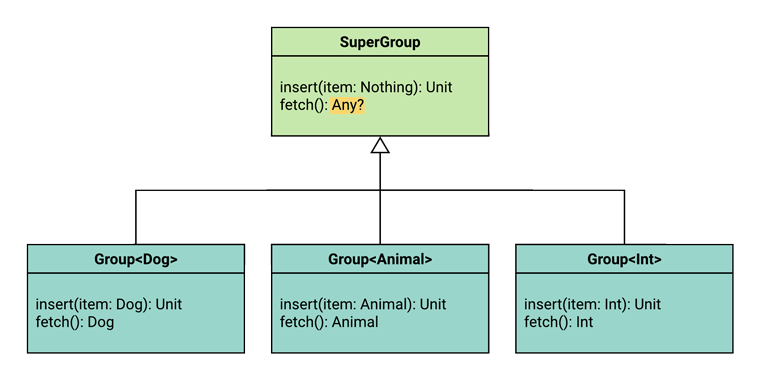

interface Group<T> {

fun insert(item: T): Unit

fun fetch(): T

}Imagine that we want Group<Dog> to be a subtype of Group<Animal>. (We call this a covariant relationship).

covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

- A subtype must accept at least the same range of types as its supertype declares.

- A subtype must return at most the same range of types as its supertype declares

covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

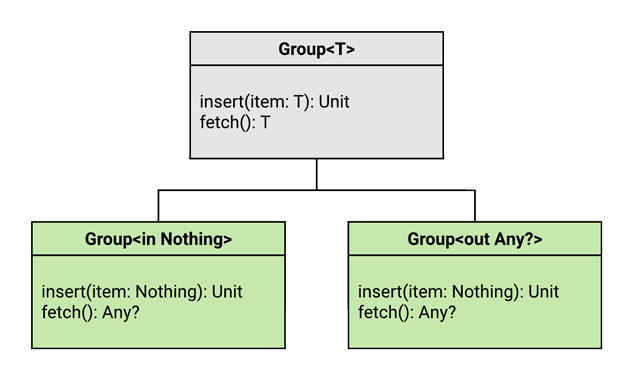

interface Group<T> {

fetch(): T

}covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

interface Group<T> {

fetch(): T

}Success! All that’s left is for us to tell the Kotlin compiler what we want. To do this, we put the out variance annotation on the type parameter T, like this:

interface Group<out T> {

fetch(): T

}

covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

It’s called out because T now only ever appears in the “out” position - as a function’s result type.

covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

By doing this, Kotlin now knows to treat Group<Dog> as a subtype of Group<Animal>.

covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

In fact, it will also enforce both of the subtype rules. So if you were to add the insert() method back, the compiler will show it as an error.

covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

And now we know why Kotlin won’t let us put a type parameter in a function parameter position when it’s marked as out - it’s not type-safe because it violates Rule #1!

covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

It’s important to note that properties are also affected

class Box<out T>(val item: T)This class has its type parameter marked as out, which works fine because val means that the property is read-only. But the following would not work:

class Box<out T>(var item: T) // doesn't compile!covariance and contravariance

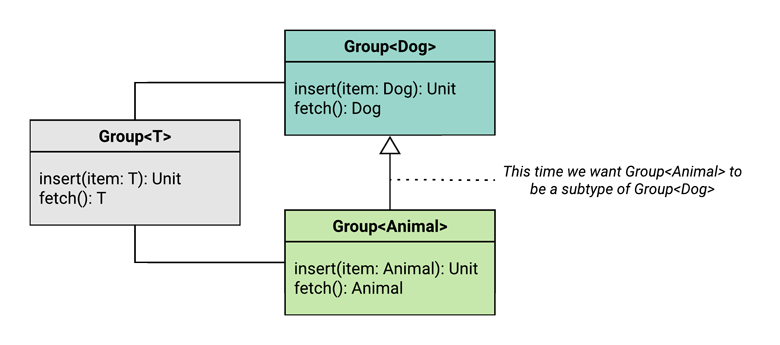

in Kotlin

Now we want a Group<Animal> to be a subtype of Group<Dog>. This is called a contravariant relationship.

covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

- A subtype must accept at least the same range of types as its supertype declares.

- A subtype must return at most the same range of types as its supertype declares

covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

interface Group<T> {

insert(item: T): Unit

}covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

interface Group<T> {

insert(item: T): Unit

}So, as before, all that we have left is to tell Kotlin that we want Group<Animal> to be a subtype of Group<Dog>, and we do that by adding the in variance annotation to T:

interface Group<in T> {

insert(item: T): Unit

}covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

Now the compiler will ensure that we don’t violate either of the two rules, so adding fetch() back into the interface would cause a compiler error.

covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

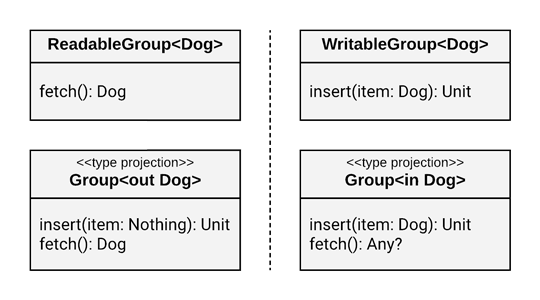

Keeping Both of Those Functions

One option is to split the interface into multiple interfaces - one with the insert() function, and one with the fetch() function.

interface WritableGroup<in T> {

fun insert(item: T): Unit

}interface ReadableGroup<out T> {

fun fetch(): T

}covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

Keeping Both of Those Functions

You’d probably still want a Group interface that includes both of those functions, and that’s easy enough to create:

interface WritableGroup<in T> {

fun insert(item: T): Unit

}interface ReadableGroup<out T> {

fun fetch(): T

}interface Group<T> : ReadableGroup<T>, WritableGroup<T>covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

Keeping Both of Those Functions

Now, anywhere in our code that we want to call fetch(), we use ReadableGroup, and anywhere that we want to call insert(), we use WritableGroup:

fun read(group: ReadableGroup<Dog>) = println(group.fetch())

fun write(group: WritableGroup<Dog>) = group.insert(Dog())covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

Keeping Both of Those Functions

Splitting up interfaces does the trick, but it’s certainly more code to write. Wouldn’t it be nifty if Kotlin gave us some way to effectively split the interfaces for us, without having to write those interfaces ourselves?

covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

Keeping Both of Those Functions

In fact, it does! Here’s how that looks:

fun read(group: Group<out Dog>) = println(group.fetch())

fun write(group: Group<in Dog>) = group.insert(Dog())covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

Until now, we’ve put the variance annotations (out and in) on the type parameter - at the point in the code where we declared the generic, which is why we call it declaration-site variance.

covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

But here, we put the variance annotations on the type argument instead - at the point in the code where we’re using the generic, so we call it use-site variance.

covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

Type Projections

The group parameter in both of these functions is now a type projection.

fun read(group: Group<out Dog>) = println(group.fetch())

fun write(group: Group<in Dog>) = group.insert(Dog())covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

Type Projections

covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

Type Projections

covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

- A subtype must accept at least the same range of types as its supertype declares.

- A subtype must return at most the same range of types as its supertype declares

covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

class Box<T>(var item: T)

fun examine(boxed: Box<out Animal>) {

val animal: Animal = boxed.item

println(animal)

}

fun insert(boxed: Box<out Animal>) {

boxed.item = Animal() // <-- compiler error here

}

val animal: Box<Animal> = Box(Animal())

val dog: Box<Dog> = Box(Dog())

examine(animal)

examine(dog)covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

In general, declaration-site variance is preferred for any code that’s under your control because the variance is specified only once, and all use sites get the benefit of the variance

covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

On the other hand, if you know that your generic will be used in different ways at different use sites, then using declaration-site variance would likely also mean creating different interfaces to separate the read and write functions. This is the main disadvantage.

covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

Declaration-Site Variance and Inheritance

interface Box<out T>{

fun get(): T

}

interface MutableBox<Y>: Box<Y>{

fun set(item: String)

}covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

Declaration-Site Variance and Inheritance

interface Box<out T>{

fun get(): T

}

interface MutableBox<Y>: Box<Y>{

fun set(item: String)

}interface Box<out T>{

fun get(): T

}

interface MutableBox<in Y>: Box<Y>{

fun set(item: String)

}covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

Declaration-Site Variance and Inheritance

interface Box<out T>{

fun get(): T

}

interface MutableBox<Y>: Box<Y>{

fun set(item: String)

}interface Box<out T>{

fun get(): T

}

interface MutableBox<in Y>: Box<Y>{

fun set(item: String)

}interface Box<T>{

fun get(): T

}

interface MutableBox<out Y>: Box<Y>{

fun set(item: String)

}covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

Declaration-Site Variance and Inheritance

interface Box<out T>{

fun get(): T

}

interface MutableBox<Y>: Box<Y>{

fun set(item: String)

}interface Box<out T>{

fun get(): T

}

interface MutableBox<in Y>: Box<Y>{

fun set(item: String)

}interface Box<T>{

fun get(): T

}

interface MutableBox<out Y>: Box<Y>{

fun set(item: String)

}covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

Declaration-Site Variance and Inheritance

interface Box<out T>{

fun get(): T

}

interface MutableBox<Y>: Box<Y>{

fun set(item: String)

}For each type parameter, a subtype can declare the same variance as its supertype, or it can effectively remove the variance declared on its supertype.

covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

@UnsafeVariance

covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

@UnsafeVariance

Yes, you can cheat on those promises! But be careful about it. You’ll lose the benefit of compile-time type guarantees, and you could end up with a ClassCastException at runtime.

covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

@UnsafeVariance

Yes, you can cheat on those promises! But be careful about it. You’ll lose the benefit of compile-time type guarantees, and you could end up with a ClassCastException at runtime.

class UnsafeBox<out T>(private var item: T) {

fun get(): T = item

fun set(newItem: @UnsafeVariance T) {

item = newItem

}

}covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

@UnsafeVariance

class UnsafeBox<out T>(private var item: T) {

fun get(): T = item

fun set(newItem: @UnsafeVariance T) {

item = newItem

}

}open class Animal

open class Dog : Animal()

open class Schnauzer : Dog()

// Because T is "out", when you call setIt(), you can pass

// either UnsafeBox<Dog> or UnsafeBox<Schnauzer>:

fun setIt(box: UnsafeBox<Dog>, dog: Dog) = box.set(dog)

val box: UnsafeBox<Schnauzer> = UnsafeBox(Schnauzer())

setIt(box, Dog()) // Oops! Passing a Dog to UnsafeBox<Schnauzer>

val schnauzer: Schnauzer = box.get() // ClassCastException!

covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

@UnsafeVariance

open class Animal

open class Dog : Animal()

open class Schnauzer : Dog()

// Because T is "out", when you call setIt(), you can pass

// either UnsafeBox<Dog> or UnsafeBox<Schnauzer>:

fun setIt(box: UnsafeBox<Dog>, dog: Dog) = box.set(dog)

val box: UnsafeBox<Schnauzer> = UnsafeBox(Schnauzer())

setIt(box, Dog()) // Oops! Passing a Dog to UnsafeBox<Schnauzer>

val schnauzer: Schnauzer = box.get() // ClassCastException!

This is especially nefarious because the exception doesn’t happen when the object is incorrectly saved to the Box. It happens when you go to pull the item back out of it.

covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

@UnsafeVariance

class Box<out T>(private var item: T) {

fun get(): T = item

fun has(other: @UnsafeVariance T) = item == other

}

covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

@UnsafeVariance

In this case, the other parameter in the has() function is never saved as object state - it’s only used for a comparison. If we were to end up comparing objects of different types, nothing would break. So we know that we won’t end up with a ClassCastException here.

class Box<out T>(private var item: T) {

fun get(): T = item

fun has(other: @UnsafeVariance T) = item == other

}

covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

@UnsafeVariance

Indeed, this is how the Kotlin standard library uses the @UnsafeVariance annotation - for testing a value, or finding the index of an object in a collection.

class Box<out T>(private var item: T) {

fun get(): T = item

fun has(other: @UnsafeVariance T) = item == other

}

covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

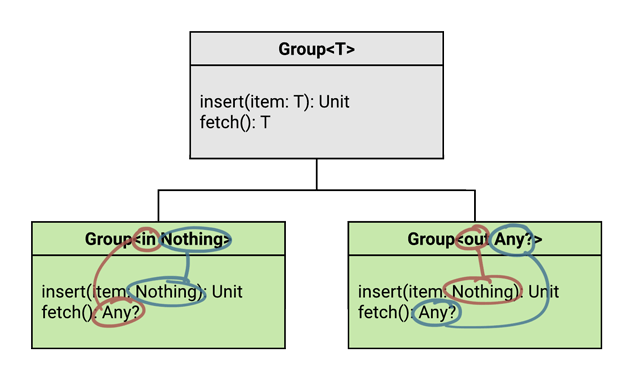

Star Projection

There are times when you want a function that can accept any kind of a particular generic.

covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

Star Projection

There are times when you want a function that can accept any kind of a particular generic.

interface Group<T> {

fun insert(item: T): Unit

fun fetch(): T

}covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

Star Projection

interface Group<T> {

fun insert(item: T): Unit

fun fetch(): T

}- A subtype must accept at least the same range of types as its supertype declares.

- A subtype must return at most the same range of types as its supertype declares

covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

Star Projection

covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

Star Projection

interface SuperGroup {

fun insert(item: Nothing): Unit

fun fetch(): Any?

}covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

Star Projection

interface SuperGroup {

fun insert(item: Nothing): Unit

fun fetch(): Any?

}It might be tempting to just create this interface in your code and have Group extend it, but that actually won’t work!

covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

Star Projection

interface SuperGroup {

fun insert(item: Nothing): Unit

fun fetch(): Any?

}It might be tempting to just create this interface in your code and have Group extend it, but that actually won’t work!

Why not?

covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

Star Projection

interface SuperGroup {

fun insert(item: Nothing): Unit

fun fetch(): Any?

}Because, as you might recall, Kotlin does not support contravariant argument types in normal class and interface inheritance.

covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

Star Projection

But good news - we can achieve the same thing with a type projection!

covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

Star Projection

Interestingly, there are two perspectives that you can take on this. You could either:

- Use an in-projection, and specify

Nothingas the type argument. - Use an out-projection, and specify

Any?as the type argument.

covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

Star Projection

covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

Star Projection

covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

Star Projection

But guess what - there’s also a third option!

covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

Star Projection

But guess what - there’s also a third option!

covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

Star Projection

Instead of using Group<in Nothing> or Group<out Any?>, you can just use Group<*>

covariance and contravariance

in Kotlin

Star Projection