Advanced ES5

Part 1

Week 1

Day 4

Segment 1

Regular Expressions

- Quantifiers

- Capture Groups

- Flags

- .test

- .match

- .exec

A regular expression, regex or regexp (sometimes called a rational expression) is, in theoretical computer science and formal language theory, a sequence of characters that define a search pattern.

| Characters | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Character | Legend | Example | Sample Match |

| \d | Most engines: one digit | ||

| from 0 to 9 | file_\d\d | file_25 | |

| \d | .NET, Python 3: one Unicode digit in any script | file_\d\d | file_9੩ |

| \w | Most engines: "word character": ASCII letter, digit or underscore | \w-\w\w\w | A-b_1 |

| \s | Most engines: "whitespace character": space, tab, newline, carriage return, vertical tab | a\sb\sc | a b c |

|---|---|---|---|

| \D | One character that is not a digit as defined by your engine's \d | \D\D\D | ABC |

| \W | One character that is not a word character as defined by your engine's \w | \W\W\W\W\W | *-+=) |

| \S | One character that is not a whitespace character as defined by your engine's \s | \S\S\S\S |

| Quantifiers | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantifier | Legend | Example | Sample Match |

| + | One or more | Version \w-\w+ | Version A-b1_1 |

| {3} | Exactly three times | \D{3} | ABC |

| {2,4} | Two to four times | \d{2,4} | 156 |

| {3,} | Three or more times | \w{3,} | regex_tutorial |

| * | Zero or more times | A*B*C* | AAACC |

| ? | Once or none | plurals? | plural |

| Logic | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Logic | Legend | Example | Sample Match |

| | | Alternation / OR operand | 22|33 | 33 |

| ( … ) | Capturing group | A(nt|pple) | Apple (captures "pple") |

| \1 | Contents of Group 1 | r(\w)g\1x | regex |

| \2 | Contents of Group 2 | (\d\d)\+(\d\d)=\2\+\1 | 12+65=65+12 |

| (?: … ) | Non-capturing group | A(?:nt|pple) | Apple |

| Quantifier | Legend | Example | Sample Match |

|---|---|---|---|

| + | The + (one or more) is "greedy" | \d+ | 12345 |

| ? | Makes quantifiers "lazy" | \d+? | 1 in 12345 |

| * | The * (zero or more) is "greedy" | A* | AAA |

| ? | Makes quantifiers "lazy" | A*? | empty in AAA |

| {2,4} | Two to four times, "greedy" | \w{2,4} | abcd |

| ? | Makes quantifiers "lazy" | \w{2,4}? | ab in abcd |

More Quantifiers

The RegExp constructor creates a regular expression object for matching text with a pattern.

var regex1 = /\w+/;

var regex2 = new RegExp('\\w+');

console.log(regex1);

// expected output: /\w+/

console.log(regex2);

// expected output: /\w+/

console.log(regex1 === regex2);

// expected output: false

Syntax

Literal, constructor, and factory notations are possible:

- /pattern/flags

- new RegExp(pattern[, flags])

- RegExp(pattern[, flags])

/ab+c/i;

new RegExp('ab+c', 'i');

new RegExp(/ab+c/, 'i');var regex1 = RegExp('foo*');

var regex2 = RegExp('foo*','g');

var str1 = 'table football';

console.log(regex1.test(str1));

// expected output: true

console.log(regex1.test(str1));

// expected output: true

console.log(regex2.test(str1));

// expected output: true

console.log(regex2.test(str1));

// expected output: false.test

regexObj.test(str)

Parameters: str The string against which to match the regular expression.

Returns: true if there is a match between the regular expression and the specified string; otherwise, false.

The exec() method executes a search for a match in a specified string. Returns a result array, or null.

Syntax

- regexObj.exec(str)

Parameters

- str

Return value

- If the match succeeds, the exec() method returns an array and updates properties of the regular expression object. The returned array has the matched text as the first item, and then one item for each capturing parenthesis that matched containing the text that was captured.

var regex1 = RegExp('foo*','g');

var str1 = 'table football, foosball';

var array1;

while ((array1 = regex1.exec(str1)) !== null) {

console.log(`Found ${array1[0]}. Next starts at ${regex1.lastIndex}.`);

// expected output: "Found foo. Next starts at 9."

// expected output: "Found foo. Next starts at 19."

}

String.prototype.match()

The match() method retrieves the matches when matching a string against a regular expression.

Syntax

- str.match(regexp)

Parameters

-

regexp

A regular expression object. If a non-RegExp object obj is passed, it is implicitly converted to a RegExp by using new RegExp(obj).

Return value

- If the string matches the expression, it will return an Array containing the entire matched string as the first element, followed by any results captured in parentheses. If there were no matches, null is returned.

var str = 'For more information, see Chapter 3.4.5.1';

var re = /see (chapter \d+(\.\d)*)/i;

var found = str.match(re);

console.log(found);

// logs [ 'see Chapter 3.4.5.1',

// 'Chapter 3.4.5.1',

// '.1',

// index: 22,

// input: 'For more information, see Chapter 3.4.5.1' ]Global/Window object

-

console

-

log

-

formatted output

-

-

setTimeout

-

setInterval

-

clearInterval

One of the most basic debugging tools in JavaScript is console.log().

Console

You can use the console to perform some of the following tasks:

- Output a timer to help with simple benchmarking

- Output a table to display an array or object in an easy-to-read format

- Apply color and other styling options to the output with CSS

var timeoutID;

function delayedAlert() {

timeoutID = window.setTimeout(slowAlert, 2000);

}

function slowAlert() {

alert('That was really slow!');

}

function clearAlert() {

window.clearTimeout(timeoutID);

}var intervalID = window.setInterval(myCallback, 500);

function myCallback() {

// Your code here

}- What Is Exception Handling?

-

Exception Handling in JavaScript

- throw

- try-catch-finally

- Error Constructors

- Stack Traces

Exception Handling

The try...catch statement marks a block of statements to try, and specifies a response, should an exception be thrown.

- In exception handling, you often group statements that are tightly coupled.

- If, while you are executing those statements, one of them causes an error, then it makes no sense to continue with the remaining statements.

What is Exception Handling?

Exception Handling in JavaScript

function throwIt(exception) {

try {

throw exception;

} catch (e) {

console.log('Caught: '+e);

}

}try {

«try_statements»

}

⟦catch («exceptionVar») {

«catch_statements»

}⟧

⟦finally {

«finally_statements»

}⟧finally is always executed, no matter what happens in try_statements (or in functions they invoke). Use it for clean-up operations that should always be performed, no matter what happens in try_statements:

try catch finally

var resource = allocateResource();

try {

...

} finally {

resource.deallocate();

}Error Constructors

- ECMAScript standardizes the following error constructors. The descriptions are quoted from the ECMAScript 5 specification:

- Error is a generic constructor for errors. All other error constructors mentioned here are subconstructors.

- EvalError “is not currently used within this specification. This object remains for compatibility with previous editions of this specification.”

- RangeError “indicates a numeric value has exceeded the allowable range.” For example:

> new Array(-1)

RangeError: Invalid array length

and more ...

Here are the properties of errors:

message

- The error message.

name

- The name of the error.

stack

- A stack trace. This is nonstandard, but is available on many platforms—for example, Chrome, Node.js, and Firefox.

Stack Traces

function catchIt() {

try {

throwIt();

} catch (e) {

console.log(e.stack); // print stack trace

}

}

function throwIt() {

throw new Error('');

}

> catchIt()

Error

at throwIt (~/examples/throwcatch.js:9:11)

at catchIt (~/examples/throwcatch.js:3:9)

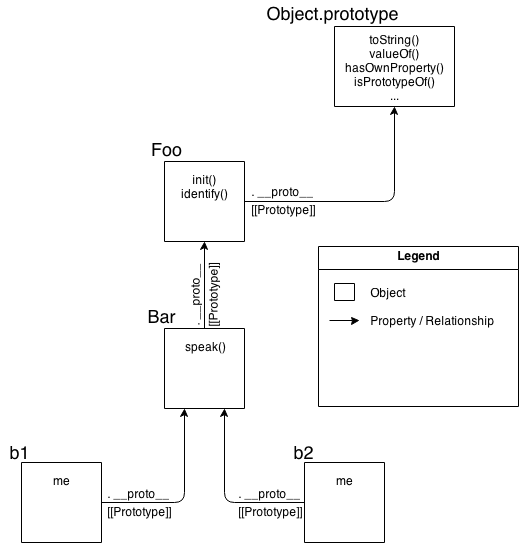

at repl:1:5Prototype Chains

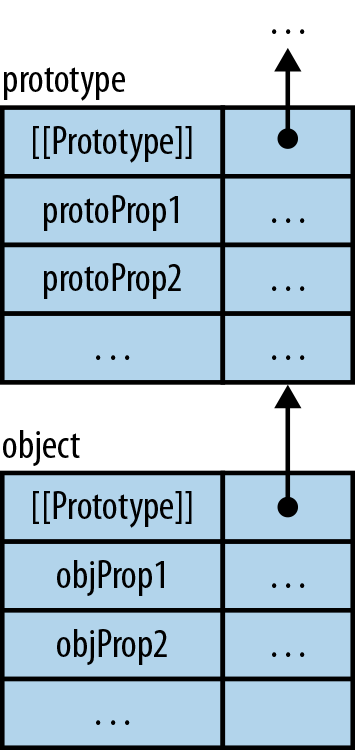

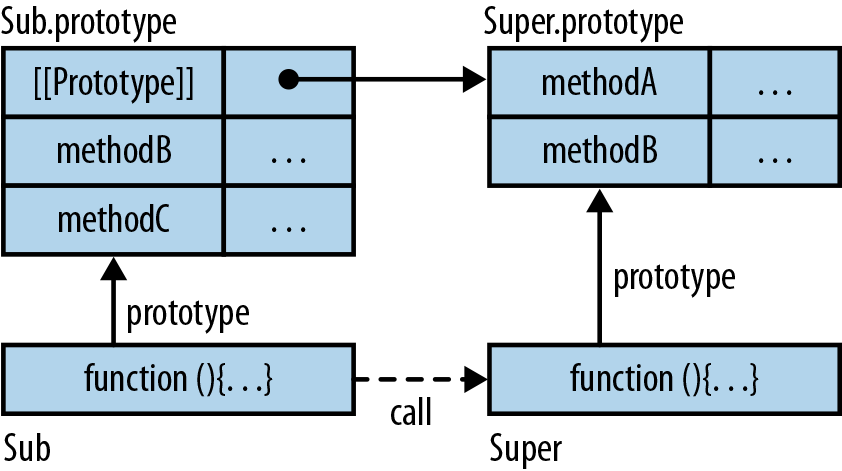

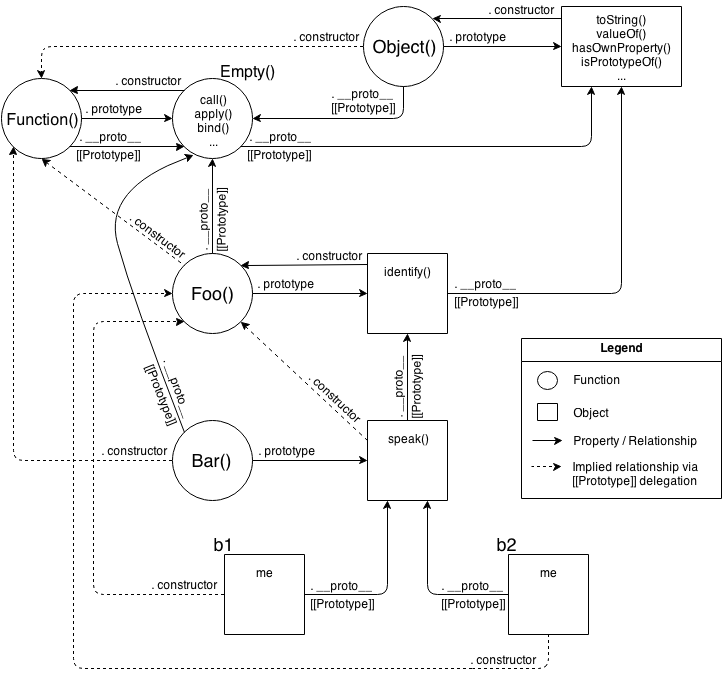

The prototype relationship between two objects is about inheritance.

An object specifies its prototype via the internal property [[Prototype]]

Every object has this property, but it can be null.

The chain of objects connected by the [[Prototype]] property is called the prototype chain

var proto = {

describe: function () {

return 'name: '+this.name;

}

};

var obj = Object.create(proto);

obj.name = 'obj';

> obj.describe();

// name: obj-

Whenever you access a property via obj, JavaScript starts the search for it in that object and continues with its prototype, the prototype’s prototype, and so on.

a property in an object overrides a property with the same key in a “later” object: the former property is found first.

-

Object reflective methods

.keys

Check out all the methods of Object here.

Accessors (Getters and Setters)

Property Attributes and Property Descriptors

-

Protecting Objects

Sealing

Extensions

Freezing

Protection Is Shallow

Iteration and Detection of Properties

Operations for iterating over and detecting properties are influenced by:

Inheritance (own properties versus inherited properties)

- An own property of an object is stored directly in that object. An inherited property is stored in one of its prototypes.

Enumerability (enumerable properties versus nonenumerable properties)

- The enumerability of a property is an attribute, a flag that can be true or false. Enumerability rarely matters and can normally be ignored

Listing Own Property Keys

You can either list all own property keys, or only enumerable ones:

- Object.getOwnPropertyNames(obj) returns the keys of all own properties of obj.

- Object.keys(obj) returns the keys of all enumerable own properties of obj.

Listing All Property Keys

Option 1 is to use the loop:

for («variable» in «object»)

«statement»

function getAllPropertyNames(obj) {

var result = [];

while (obj) {

// Add the own property names of `obj` to `result`

result = result.concat(Object.getOwnPropertyNames(obj));

obj = Object.getPrototypeOf(obj);

}

return result;

}

Checking Whether a Property Exists

propKey in obj

- Returns true if obj has a property whose key is propKey. Inherited properties are included in this test.

Object.prototype.hasOwnProperty(propKey)

- Returns true if the receiver (this) has an own (noninherited) property whose key is propKey.

Accessors (Getters and Setters)

Defining Accessors via an Object Literal

ECMAScript 5 lets you write methods whose invocations look like you are getting or setting a property.

var obj = {

get foo() {

return 'getter';

},

set foo(value) {

console.log('setter: '+value);

}

};

> obj.foo = 'bla';

setter: bla

> obj.foo

'getter'

Defining Accessors via Property Descriptors

An alternate way to specify getters and setters is via property descriptors. The following code defines the same object as the preceding literal:

var obj = Object.create(

Object.prototype, { // object with property descriptors

foo: { // property descriptor

get: function () {

return 'getter';

},

set: function (value) {

console.log('setter: '+value);

}

}

}

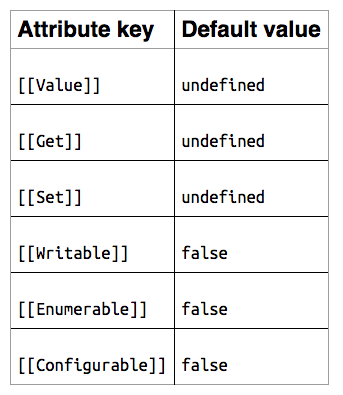

);Property Attributes and Property Descriptors

In this section, we’ll look at the internal structure of properties:

- Property attributes are the atomic building blocks of properties.

- A property descriptor is a data structure for working programmatically with attributes.

Property Attributes

- All of a property’s state, both its data and its metadata, is stored in attributes.

- They are fields that a property has, much like an object has properties.

The following attributes are specific to normal properties:

- [[Value]] holds the property’s value, its data.

- [[Writable]] holds a boolean indicating whether the value of a property can be changed.

The following attributes are specific to accessors:

- [[Get]] holds the getter, a function that is called when a property is read. The function computes the result of the read access.

- [[Set]] holds the setter, a function that is called when a property is set to a value. The function receives that value as a parameter.

All properties have the following attributes:

- [[Enumerable]] holds a boolean. Making a property nonenumerable hides it from some operations (see Iteration and Detection of Properties).

- [[Configurable]] holds a boolean. If it is false, you cannot delete a property, change any of its attributes (except [[Value]]), or convert it from a data property to an accessor property or vice versa.

- In other words, [[Configurable]] controls the writability of a property’s metadata.

Default values

If you don’t specify attributes, the following defaults are used:

Property Descriptors

- A property descriptor is a data structure for working programmatically with attributes.

- It is an object that encodes the attributes of a property.

- Each of a descriptor’s properties corresponds to an attribute.

{

value: 123,

writable: false,

enumerable: true,

configurable: false

}

You can achieve the same goal, immutability, via accessors. Then the descriptor looks as follows:

{

get: function () { return 123 },

enumerable: true,

configurable: false

}

Protecting Objects

There are three levels of protecting an object, listed here from weakest to strongest:

- Preventing extensions

- Sealing

- Freezing

Preventing Extensions

Preventing extensions via:

- Object.preventExtensions(obj)

makes it impossible to add properties to obj. For example:

- var obj = { foo: 'a' };

You check whether an object is extensible via: Object.isExtensible(obj)

Sealing

Sealing via:

Object.seal(obj)

prevents extensions and makes all properties “unconfigurable.”

Freezing

Freezing is performed via:

Object.freeze(obj)

It makes all properties nonwritable and seals obj. In other words, obj is not extensible and all properties are read-only, and there is no way to change that.

-

What are pure functions and why use them?

-

Pure versus impure functions

-

Partial Functions

-

Functional perspective

-

Decoupling methods from their objects

-

Function Composition For Every Day Use.

-

-

Why it's better than loops

-

map vs forEach vs for

-

Rethinking JavaScript: Death of the For Loop

-

Functional Approach