The Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Periods (449-1485)

The Dark Ages. Mud. Muck. Filth. If you were alive during the time, you were most likely a peasant eking out a meager existence. If you were very lucky, you might have been born into a noble family . . .

Invade Me!

-

Julius Caesar was the first to attempt a full-scale invasion of the British Isles in 55 B.C. Upon encountering great resistance from Celtic warriors, Caesar claimed victory for Rome and swiftly retreated.

Julius Caesar, after attempting to tangle with the Celtic warriors:

Eventually, Rome did manage to properly invade and annex the British Isles. The Romans introduced things like:

- public baths

- villas

- decent roads

The Angles and Saxons (two Germanic tribes) took advantage of Rome's absence and started settling in the British Isles. This angered the Britons, who--possibly led by the legendary King Arthur--waged a series of ultimately unsuccessful military campaigns against the invaders.

After the Angles and Saxons were firmly ensconced, the land became known as Angle-land (or England). People spoke a curiously guttural language that we now know as Old English. It sounded like this:

Invasion! (pt. 3)

Next to jump on the invasion bandwagon (starting in the 790s) were the Vikings, a seafaring people from Denmark and Norway. The Vikings were not particularly nice people: they would commonly pillage villages, kill the villages' men, and rape the villages' women. This is quite different from how Vikings are portrayed in the comic strip, Hagar the Horrible.

It took a great king--Alfred the Great--to finally drive the Vikings from England. Although primarily portrayed as a formidable warrior, Alfred was very concerned with supporting education and cultural growth in his kingdom.

Alfred the Great after vanquishing the Vikings.

Royal Kerfuffle

Edward the Confessor (a descendant of Alfred) ascended to the throne in 1042. Apparently, Edward promised to make his French cousin, William of Normandy, his heir. But when Edward died, some officials decided to make an English earl named Harold king. William was not pleased . . .

Harold (after learning that he would be king) to William:

Stormin' Normans

William attacked and defeated Harold at the Battle of Hastings in 1066 A.D. For this, he became known as William the Conqueror. Thus ended the dominance of Anglo-Saxon culture in England. Norman (French) nobles took the place of Anglo-Saxon nobles, and French became the language of the courts/power.

Shifting Values

The early Anglo-Saxons believed in something called Wyrd. Wyrd was akin to our conception of fate. If you had good wyrd, good things would happen to you. If your wyrd was bad, no one would write a ballad about you, and you'd probably get invaded by the Vikings.

But wyrd's days were numbered. Around 600 A.D., Christianity supplanted the older, pagan beliefs of the Anglo-Saxons. A missionary named Augustine (best known for his theological/philosophical autobiography, Confessions) began spreading Christianity. Soon, monasteries were popping up all over the place.

Epics

Anglo-Saxon literature was all about epics. Epic poems praised the deeds of heroic warriors, magnifying their greatness in a prism of exaggeration and hyperbole. Epic poems were often recounted in mead halls (giant feasting rooms) by Scops (professional poets).

Domesday Doomsday

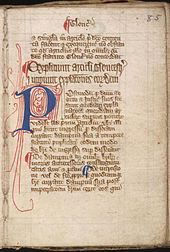

In 1086 A.D., a substantial survey of English land and property was published. Compiled at the behest of William I (The Conqueror, formerly of Normandy), the census was undertaken to determine the amount of taxes every citizen owed the crown.

It was popularly called the "Domesday Book" because, like the day of judgement (Doomsday), what was written in the Domesday Book was unalterable.

Magna Carta

Latin for "Great Charter," the Magna Carta was a document of extreme importance. Issued in 1215 A.D. by a bunch of Barons, the Magna Carta curtailed and limited King John's power.

not to be confused with

not to be confused with ![]()

More War

A disagreement over who was the rightful king of France (Edward III of England or Philip VI of France) led to the Hundred Years' War. It lasted from 1337 A.D. to 1453 A.D., so it really should be called the 116 Years' War.

Flora War?

After the Hundred Years' War, there was a little disagreement about who deserved the English throne: the House of York or the House of Lancaster. The two families duked it out in what came to be known as the War of the Roses. Lancaster won when Henry Tudor defeated Richard III at Bosworth Field.

Lancaster York

Lancaster York

Serfing U.K.

William I introduced a new political/economic system in England when he became king: feudalism. At the top of the pecking order was the king, who kept 1/4 of all available land for himself. Next was the church, which also got 1/4 of the land. At the bottom were the Serfs, who couldn't own land at all.

The Church

The only institution that regularly challenged the monarchy's power was the church. If you upset the church, you could be excommunicated. The Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Becket, went a little too far in challenging the king's authority and was brutally murdered by knights serving Henry II. Read This pleasant description of the details--only for the strong of stomach!

Beowulf to Gawain

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight

- Le Morte d'Arthur