Analysis: the opening sequence from “Interstellar” (2014)

By: Muhammad Faraz Malik

Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar is a science-fiction epic unlike any other. It features strong performances, Academy Award-winning visual effects, an elaborate score by Hans Zimmer and stunning cinematography by Hoyte van Hoytema. It is my personal all-time favorite film.

The film starts with production and distribution logos, tinted in sepia tone, to set a dystopian mood. The first shot is of Murphy’s (Mackenzie Foy) bookshelf. Zimmer’s score can be heard fading in at this point. Dust particles can be seen drifting around in the shot. The title then appears overlaid.

Both the bookshelf and dust particles are a narrative foreshadowing, because they are later revealed to be essential plot devices: it is the pouring of the dust particles that allows Cooper (Matthew McConaughey) to notice the gravitational anomaly in his house, and it is the bookshelf through which Cooper communicates with Murphy across time and space. The significance of the bookshelf is one of myriad enigmas set up in this sequence.

There is a cut to black, and there is voiceover by Murphy (in her elder years), and the film then cuts to a close-up shot of her, speaking towards in the camera in what seems to be an interview.

The idea that this is interview footage is further reinforced by the change in aspect ratios: the shots of Murphy are in 1:85:1, while everything else is in 2:35:1. This sets up another enigma, because the inclusion of interviews implies that something of public interest happens in the course of the movie, and also, the identity of the woman being interviewed is unknown to the viewer. As she discusses her father being a farmer, there is a wide, symmetrically composed shot of a cornfield.

The monochromatic, slightly warm and desaturated color scheme of this shot serves as another indication of the dystopian nature of the shown time period.

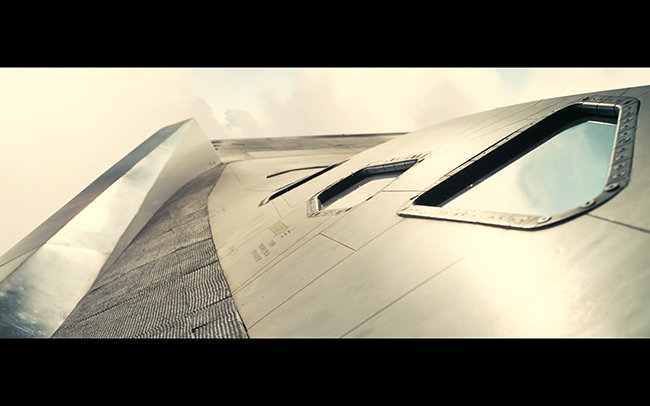

There is an abrupt cut to a flying aircraft.

With an over-the-shoulder shot, we are introduced to Cooper, who is flying it.

There is some kind of crisis, and it is implied that the aircraft crashes. The sound design is chaotic here, but the scene comes to an abrupt halt, when Cooper is revealed to be dreaming.

This cut results in a very stark shift in color schemes: the aircraft sequence is highly overexposed, and composed of whites and greys, while the shots in the bedroom are very dark and contain only blacks and dark blues. We see him wake up in his bed, and we see his daughter, Murphy, at the door, asking him if he was “dreaming about the crash”.

This indicates that the crash is something that actually happened and not just a creation of his mind, but the context for the crash remains an enigma, one that is never truly resolved. This scene also acts as a good introduction to Murphy; while most children would be apprehensive about dealing with their parents during (presumably) a PTSD flashback, she is not. This fearlessness remains a predominant trait of hers throughout the movie.

Cooper then gets out of bed and looks out of his bedroom window, out to the cornfield of his farm.

The camera pans to show a wide shot, which maintains the primarily blue color scheme of the sequence, and the score swells here.

There is another cut to the interview footage, then another shot of the cornfield (which, here, is blowing more violently in the heavy wind and dust), and then there is a cut to an interview of a different subject, who describes the excess of dust in the air, in the shown time period.

There is another wide shot of the farm, which features Cooper’s father-in-law (John Lithgow) cleaning his front porch.

As he cleans, a large amount of dust blows off of the surface of the porch. The film cuts to the interior of the home, where Cooper, his father-in-law and his two children live. It is shown that a large amount of dust has covered every surface in the kitchen, and it is wiped away by Cooper’s father-in-law.

While Cooper’s father-in-law is shown cleaning the dining room, there is more interview footage of two more subjects, who further describe conditions in this dystopian time period. Their descriptions are retrospective, which reveals that these interviews are from the future, where mankind has somehow repaired the suffocating environment.

Finally, there is a scene in the dining room, where Cooper and Murphy discuss her observation of a “poltergeist” in her room.

This is another narrative foreshadowing, because this “poltergeist” is of great significance later in the film. We are also introduced to Cooper’s son (Timothée Chalamet).

There is much to note about some of the technical aspects of this opening. Firstly, the Academy-Award nominated sound design is interesting; it allows the score and the Foley track a lot of sonic room, while much of the dialogue is largely drowned out. During the initial theatrical run of the movie, this drew complaints from moviegoers, who believed that this was a technical error on the theaters’ part. However, this was deliberate, and it allows the viewer to experience the film more as an aesthetic work rather than a narrative one; to imbibe it rather than to analyze it.

The editing here is quick and abrupt, and it does not use any soft transitions. It vacillates between shots of widely varying subjects (elderly interviewees, an aircraft, a cornfield, a house, a kitchen, a bedroom) with little graphic or aesthetic contiguity. There is also a great range of cinematographic technique (close-ups, OTS shots, wide shots, low-angle shots etc.), and there is a very varietal color palette used. In the original theatrical version shown in IMAX-equipped theaters, even the aspect ratio varied to allow some shots more onscreen room. Cohesion is instead largely maintained by Zimmer’s score, which is dynamic and expressive, and it gives the sequence an overarching sense of grim uncertainty.