COMP6771

Advanced C++ Programming

Week 5.2

Smart Pointers

A recapt on pointers

Object lifetimes

To create safe object lifetimes in C++, we always attach the lifetime of one object to that of something else

-

Named objects:

- A variable in a function is tied to its scope

- A data member is tied to the lifetime of the class instance

- An element in a std::vector is tied to the lifetime of the vector

-

Unnamed objects:

- A heap object should be tied to the lifetime of whatever object created it

-

Examples of bad programming practice

- An owning raw pointer is tied to nothing

- A C-style array is tied to nothing

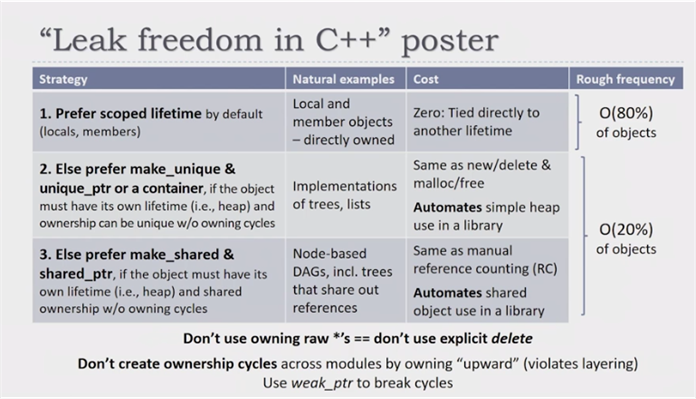

- Strongly recommend watching the first 44 minutes of Herb Sutter's cppcon talk "Leak freedom in C++... By Default"

Object lifetime with references

We need to be very careful when returning references.

The object must always outlive reference.

auto okay(int& i) -> int& {

return i;

}

auto okay(int& i) -> int const& {

return i;

}auto questionable(int const& x) -> int const& {

return i;

}

auto not_okay(int i) -> int& {

return i;

}

auto not_okay() -> int& {

auto i = 0;

return i;

}Creating a safe* pointer type

// myintpointer.h

class MyIntPointer {

public:

// This is the constructor

MyIntPointer(int* value);

// This is the destructor

~MyIntPointer();

int* GetValue();

private:

int* value_;

};// myintpointer.cpp

#include "myintpointer.h"

MyIntPointer::MyIntPointer(int* value): value_{value} {}

int* MyIntPointer::GetValue() {

return value_

}

MyIntPointer::~MyIntPointer() {

// Similar to C's free function.

delete value_;

}Don't use the new / delete keyword in your own code

We are showing for demonstration purposes

void fn() {

// Similar to C's malloc

MyIntPointer p{new int{5}};

// Copy the pointer;

MyIntPointer q{p.GetValue()};

// p and q are both now destructed.

// What happens?

}Smart Pointers

- Ways of wrapping unnamed (i.e. raw pointer) heap objects in named stack objects so that object lifetimes can be managed much easier

- Introduced in C++11

- Usually two ways of approaching problems:

- unique_ptr + raw pointers ("observers")

- shared_ptr + weak_ptr/raw pointers

| Type | Shared ownership | Take ownership |

|---|---|---|

| std::unique_ptr<T> | No | Yes |

| raw pointers | No | No |

| std::shared_ptr<T> | Yes | Yes |

| std::weak_ptr<T> | No | No |

Unique pointer

-

std::unique_pointer<T>

- The unique pointer owns the object

- When the unique pointer is destructed, the underlying object is too

-

raw pointer (observer)

- Unique Ptr may have many observers

- This is an appropriate use of raw pointers (or references) in C++

- Once the original pointer is destructed, you must ensure you don't access the raw pointers (no checks exist)

- These observers do not have ownership of the pointer

Also note the use of 'nullptr' in C++ instead of NULL

Unique pointer: Usage

#include <memory>

#include <iostream>

int main() {

std::unique_ptr<int> up1{new int};

std::unique_ptr<int> up2 = up1; // no copy constructor

std::unique_ptr<int> up3;

up3 = up2; // no copy assignment

up3.reset(up1.release()); // OK

std::unique_ptr<int> up4 = std::move(up3); // OK

std::cout << up4.get() << "\n";

std::cout << *up4 << "\n";

std::cout << *up1 << "\n";

}Can we remove "new" completely?

Observer Ptr: Usage

#include <memory>

#include <iostream>

int main() {

std::unique_ptr<int> up1(new int{0});

*up1 = 5;

std::cout << *up1 << "\n";

int* op1 = up1.get();

*op1 = 6;

std::cout << *op1 << "\n";

up1.reset();

std::cout << *op1 << "\n";

}Unique Ptr Operators

#include <memory>

#include <iostream>

int main() {

// 1 - Worst - you can accidentally own the resource multiple

// times, or easily forget to own it.

int *i = new int;

auto up1 = std::make_unique<std::string>(i);

auto up11 = std::make_unique<std::string>(i);

// 2 - Not good - requires actual thinking about whether there's a leak.

std::unique_ptr<std::string> up2{new std::string{"Hello"}};

// 3 - Good - no thinking required.

std::unique_ptr<std::string> up3 = std::make_unique<std::string>("Hello");

std::cout << *up3 << "\n";

std::cout << *(up3.get()) << "\n";

std::cout << up3->size();

}Shared pointer

- std::shared_pointer<T>

-

Several shared pointers share ownership of the object

- A reference counted pointer

- When a shared pointer is destructed, if it is the only shared pointer left pointing at the object, then the object is destroyed

-

May also have many observers

- Just because the pointer has shared ownership doesn't mean the observers should get ownership too - don't mindlessly copy it

-

std::weak_ptr<T>

-

Weak pointers are used with share pointers when:

- You don't want to add to the reference count

- You want to be able to check if the underlying data is still valid before using it.

-

Weak pointers are used with share pointers when:

Shared pointer: Usage

#include <memory>

#include <iostream>

int main() {

std::shared_ptr<int> x(new int{5});

std::shared_ptr<int> y = x; // Both now own the memory

std::cout << "use count: " << x.use_count() << "\n";

std::cout << "value: " << *x << "\n";

x.reset(); // Memory still exists, due to y.

std::cout << "use count: " << y.use_count() << "\n";

std::cout << "value: " << *y << "\n";

y.reset(); // Deletes the memory, since

// no one else owns the memory

std::cout << "use count: " << x.use_count() << "\n";

std::cout << "value: " << *y << "\n";

}Can we remove "new" completely?

Weak Pointer: Usage

#include <memory>

#include <iostream>

int main() {

std::shared_ptr<int> x = std::make_shared<int>(1);

std::weak_ptr<int> wp = x; // x owns the memory

{

std::shared_ptr<int> y = wp.lock(); // x and y own the memory

if (y) {

// Do something with y

std::cout << "Attempt 1: " << *y << '\n';

}

} // y is destroyed. Memory is owned by x

x.reset(); // Memory is deleted

std::shared_ptr<int> z = wp.lock(); // Memory gone; get null ptr

if (z) {

// will not execute this

std::cout << "Attempt 2: " << *z << '\n';

}

}When to use which type

-

Unique pointer vs shared pointer

- You almost always want a unique pointer over a shared pointer

-

Use a shared pointer if either:

- An object has multiple owners, and you don't know which one will stay around the longest

- You need temporary ownership (outside scope of this course)

- This is very rare

When to use which type

-

Let's look at an example:

- //lectures/week5/reader.cpp

Shared or unique pointer?

-

Computing examples

- Linked list

- Doubly linked list

- Tree

- DAG (mutable and non-mutable)

- Graph (mutable and non-mutable)

- Twitter feed with multiple sections (eg. my posts, popular posts)

-

Real-world examples

- The screen in this lecture theatre

- The lights in this room

- A hotel keycard

- Lockers in a school

Stack unwinding

- Stack unwinding is the process of exiting the stack frames until we find an exception handler for the function

-

This calls any destructors on the way out

- Any resources not managed by destructors won't get freed up

- If an exception is thrown during stack unwinding, std::terminate is called

void g() {

throw std::runtime_error{""};

}

int main() {

auto ptr = new int{5};

g();

// Never executed.

delete ptr;

}void g() {

throw std::runtime_error{""};

}

int main() {

auto ptr = std::make_unique<int>(5);

g();

}Not safe

Safe

Exceptions & Destructors

- During stack unwinding, std::terminate() will be called if an exception leaves a destructor

- The resources may not be released properly if an exception leaves a destructor

- All exceptions that occur inside a destructor should be handled inside the destructor

-

Destructors usually don't throw, and need to explicitly opt in to throwing

- STL types don't do that

RAII

-

Resource acquisition is initialisation

-

A concept where we encapsulate resources inside objects

- Acquire the resource in the constructor

- Release the resource in the destructor

-

eg. Memory, locks, files

-

Every resource should be owned by either:

-

Another resource (eg. smart pointer, data member)

-

The stack

-

A nameless temporary variable

-

Partial construction

-

What happens if an exception is thrown halfway through a constructor?

- The C++ standard: "An object that is partially constructed or partially destroyed will have destructors executed for all of its fully constructed subobjects"

- A destructor is not called for an object that was partially constructed

- Except for an exception thrown in a constructor that delegates (why?)

#include <exception>

class my_int {

public:

my_int(int const i) : i_{i} {

if (i == 2) {

throw std::exception();

}

}

private:

int i_;

};

class unsafe_class {

public:

unsafe_class(int a, int b)

: a_{new my_int{a}}

, b_{new my_int{b}}

{}

~unsafe_class() {

delete a_;

delete b_;

}

private:

my_int* a_;

my_int* b_;

};

int main() {

auto a = unsafe_class(1, 2);

}Spot the bug

Partial construction: Solution

-

Option 1: Try / catch in the constructor

- Very messy, but works (if you get it right...)

- Doesn't work with initialiser lists (needs to be in the body)

-

Option 2:

-

An object managing a resource should initialise the resource last

- The resource is only initialised when the whole object is

- Consequence: An object can only manage one resource

- If you want to manage multiple resources, instead manage several wrappers , which each manage one resource

-

An object managing a resource should initialise the resource last

#include <exception>

#include <memory>

class my_int {

public:

my_int(int const i)

: i_{i} {

if (i == 2) {

throw std::exception();

}

}

private:

int i_;

};

class safe_class {

public:

safe_class(int a, int b)

: a_(std::make_unique<my_int>(a))

, b_(std::make_unique<my_int>(b))

{}

private:

std::unique_ptr<my_int> a_;

std::unique_ptr<my_int> b_;

};

int main() {

auto a = safe_class(1, 2);

}Reference types

We learnt about references to objects in Week 1.

We learnt about containers, iterators, and views in Week 2.

We've just learnt about smart pointers in Week 4.

How do they all tie together and what's the relationship with pointers?

Reference types

class string_view6771 {

public:

string_view6771() noexcept = default;

explicit(false) string_view6771(std::string const& s) noexcept

: string_view6771(s.data())

{}

explicit(false) string_view6771(char const* data) noexcept

: string_view6771(data, std::strlen(data))

{}

string_view6771(char const* data, std::size_t const length) noexcept

: data_{data}

, length_{length}

{}

auto begin() const noexcept -> char const* { return data_; }

auto end() const noexcept -> char const* { return data_ + length_; }

auto size() const noexcept -> std::size_t { return length_; }

auto data() const noexcept -> char const* { return data_; }

auto operator[](std::size_t const n) const noexcept -> char {

assert(n < length_);

return data_[n];

}

private:

char const* data_ = nullptr;

std::size_t length_ = 0;

};A reference type is a type that acts as an abstraction over a raw pointer.

They don't own a resource, but allow us to do cheap operations like copy, move, and destroy (see Week 5) on objects that do.

A reference type to a range of elements is called a view.

Reference types

Abstraction over immutable string-like data.

Abstraction over array-like data.

std::span<T const>

ranges::views::*

Raw pointer to a single object or to an element in a range. Wherever possible, prefer references, iterators, or something below.

T const*

Lazy abstraction over a range, associated with some transformation.

Most

A quick look at span

auto zero_out(std::span<int> const x) -> void {

ranges::fill(x, 0);

}

{

auto numbers = views::iota(0, 100) | ranges::to<std::vector>;

zero_out(numbers);

CHECK(ranges::all_of(numbers, [](int const x) { return x == 0; }));

}

{

// Using int[] since spec requires we use T[] instead of std::vector

// NOLINTNEXTLINE(modernize-avoid-c-arrays)

auto const raw_data = std::make_unique<int[]>(42);

auto const usable_data = std::span<int>(raw_data.get(), 42);

zero_out(usable_data);

CHECK(ranges::all_of(usable_data, [](int const x) { return x == 0; }));

}NOLINTNEXTLINE(check) turns off a check on the following line.

Do this rarely, and always provide justification immediately above.

A quick look at span

auto zero_exists(std::span<int const> const x) -> bool {

ranges::any_of(x, [](int const x) { return x == 0; });

}

{

auto numbers = views::iota(0, 100) | ranges::to<std::vector>;

CHECK(zero_exists(numbers));

}

{

// Using int[] since ass2 spec requires we use T[] instead of std::vector

// NOLINTNEXTLINE(modernize-avoid-c-arrays)

auto const raw_data = std::make_unique<int[]>(42);

auto const usable_data = std::span<int>(raw_data.get(), 42);

CHECK(zero_exists(usable_data));

}NOLINTNEXTLINE(check) turns off a check on the following line.

Do this rarely, and always provide justification immediately above.

Iterators and pointers

A pointer is an abstraction of a virtual memory address.

Iterators are a generalization of pointers that allow a C++ program to work with different data structures... in a uniform manner.

Iterators are a family of concepts that abstract different aspects of addresses, ...

Ownership and lifetime with reference types

We need to be very careful when using reference types.

The owner must always outlive the observer.

auto v = std::vector<int>{0, 1, 2, 3};

auto const* p = v.data();

{

CHECK(*p == 0); // okay: p points to memory

// owned by v

}

v = std::vector<int>{0, 1, 2, 3};

{

CHECK(*p == 0); // error: p points to memory

// owned by no one

}Ownership and lifetime with reference types

We need to be very careful when using reference types.

The owner must always outlive the observer.

auto not_okay1(std::string s) -> std::string_view { // s is a local; will be destroyed

return s; // before its observer

} // s destroyed here

auto not_okay2(std::string const& s) -> std::string_view { // s may be destroyed before observer;

return s; // considered harmful

} // e.g. auto x = not_okay("hello")

auto okay1(std::string_view const sv) -> std::string_view { // observer in, observer out

return sv;

}

auto okay2(std::string& s) -> std::string_view { // lvalue reference in, observer out

return s;

}Ownership and lifetime with reference types

We need to be very careful when using reference types.

The owner must always outlive the observer.

auto is_even(int const x) -> bool {

return x % 2 == 0;

};

auto not_okay1(std::vector<int> v) {

return v | views::filter(is_even);

} // v destroyed here

auto not_okay2(std::vector<int> const& v) {

return v | views::filter(is_even);

}auto okay1(std::span<int> s) {

return s | views::filter(is_even);

}

auto okay2(std::vector<int>& v) {

return v | views::filter(is_even);

}Partial construction

Grab from old week 4