Sarah Clark, University of Manitoba

Dom Taylor, University of Manitoba

LILAC 2019, Nottingham, England

Holistic scaffolding and the pedagogy of charity

Learning objectives

1.

Introduction to understanding and using a holistic method of instruction.

2.

3.

Considering the role of strengths-based teaching.

Approaching scaffolding as a collaborative experience between learners and instructors.

plan

1.

Holism

2.

Scaffolding

3.

4.

Example 1

Principle of charity

THEORY

PRACTICE

5.

Example 2

CONCLUSION + TAKEAWAYS

theory

Conceptual Holism

- Using one concept (via language) is dependent on being able to use many other concepts (Brandom, 1994; Sellars,1997).

- Example: Using the concept 'green' implies that one knows what ‘green’ is, what, ‘not green’ is, and that ‘green’ is something incompatible with ‘red’.

Pedagogical holism

- Learning is a process that relies on learning to use multitudes of interdependent socio-historical concepts (Tomasello, 2014 & 2019).

- Learning is necessarily social (Tomasello, 2014 & 2019).

- Learning is not purely piecemeal and/or linear, but given conceptual holism, relies on grasping multiple concepts and norms for any given activity.

- Example: To know how to cite properly, you must not only able to apply a given style guide, but also be able to paraphrase , research, and read critically (and much more).

Conceptual charity

- In order to communicate, we need to assume (Davidson, 2001):

- Self-knowledge (e.g., of intentions, beliefs, desires)

- Knowledge of a shared world (basic capacity to coordinate actions)

- An interlocutor with the above two capacities, as well as a holistic set of accurate concepts commensurable with one’s own.

- Charity, the above assumptions, is a necessary condition for meaningful communication between interlocutors.

- This is a social understanding of concept use. Concept use develops out of small and then large group coordination of collective activities and shared plans (Bratman, 2014; Tomasello, 2014)

Pedagogical charity

- The use of conceptual charity within the context of teaching/learning.

- Emphasizes the capacities of students, rather than their deficits:

- Informal research experience

- Significant practical problem-solving knowledge

- Years of communicating, which itself necessitates being a competent knower/testifier

- Focuses on making explicit skills and knowledge students already make use of competent knowers/testifiers (cf.Brandom, 1994).

Pedagogical charity

- Conceptual charity allows us to make a pragmatic as well as moral argument for pedagogical charity.

- Pragmatic: Given conceptual charity, we cannot start from a "deficit" model of teaching (Martin, 2011). To communicate, we have to treat students as competent knowers/testifiers.

- Moral: Given conceptual charity, it is an epistemic injustice to not treat students as capable knowers/testifiers. Epistemic injustices include assuming the incompetence of students or discounting students' methods of knowing off-hand (Fricker, 2007).

Scaffolding

A tutoring approach that...

(Wood, Bruner, & Ross, 1976, p. 90)

“enables a child or novice to solve a problem, carry out a task or achieve a goal which would be beyond his unassisted efforts...It may result, eventually, in development of task competence by the learner at a pace that would far outstrip his unassisted efforts.”

Perceived benefits of scaffolding

In our context, scaffolding focuses on supporting learners (UG students) as they develop a variety of research skills.

This can involve:

- reducing the cognitive burden within a task so that the learner can focus on key elements

- providing multiple opportunities for the learner to develop the particular competence

- providing feedback throughout the process that helps the learner move to a deeper level of competence

Limitation of scaffolding

"The scaffolding metaphor supposes a predefined system of goals and leaves little space for a [learner's] creativity" (Shvarts & Bakker, 2019, p.2).

Holistic Scaffolding

- Holistic scaffolding (HS) emphasizes the co-development of interrelated concepts through practice (i.e., use) rather than a linear progression through concept definition followed by practice.

- One of the aims of HS is to leverage learners' existing capabilities--the outgrowth of social relations--rather than building from the "ground up."

- Therefore, the "scaffolding" is not assembled by the teacher, but made explicit or uncovered through practice with learners (cf.Wood et al., 1976).

LEARNER

TEACHER

{

MAKING CONCEPTS EXPLICIT THROUGH INTERACTION AND ACTIVITY

Holistic Scaffolding

CONCEPTUAL SCAFFOLDING

IMPLICIT CAPACITIES

EXPLICIT CAPABILITIES

SHARED SOCIAL WORLD

HS for library instruction

- In spite of Davidson's ideas about charity (value of shared holistic beliefs; necessary for successful communication), the library literature draws on students' unfamiliarity regarding the application of research and writing skills

- This lack of understanding is referred to as a "deficit that inevitably causes stress and leads to ill-conceived measures of last resort, such as copying and pasting" (Greer, Swanberg, Hristovda, Switzer, Daniel & Perdue, 2012, p. 251).

What is the library doing to address these issues?

HS for library instruction

- Emphasis on one-shot sessions focused on finding peer-reviewed sources, although this is just one piece of the overall research process

- "What good is teaching students how to find scholarly resources if they can't read them?" (MacMillan & Rosenblatt, 2015, p. 757)

-

Cortes-Vera, Garcia and Gutierrez (2017) consider paraphrasing essential for IL, but admit that "little time is spent focusing on teaching how to write correctly" (p. 493)

- These ideas provide a rationale for moving forward with HS in library instruction

practice

Busari, Stephanie. “Stefanie Busari: How Fake News Does Real Harm.” YouTube, uploaded by TED, 18 May 2017 www.youtube.com/watch?v=lwVYaY39YbQ.

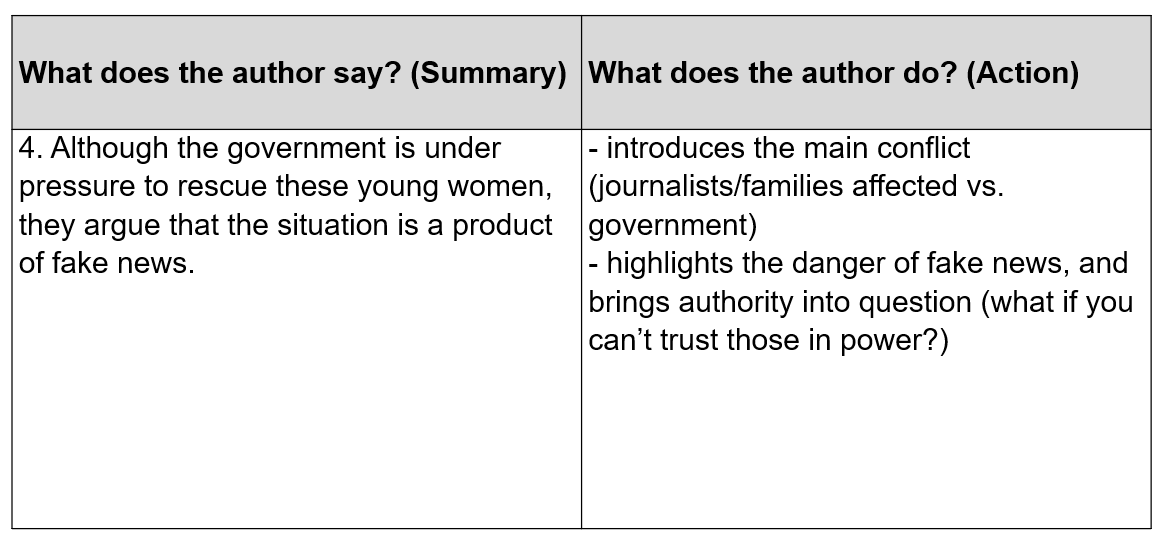

Critical reading: Say + Do

Activity: Students view a brief TedTalk and consider what the speaker is saying (summary) as well as why they might be saying it (action).

Critical reading: Say + Do

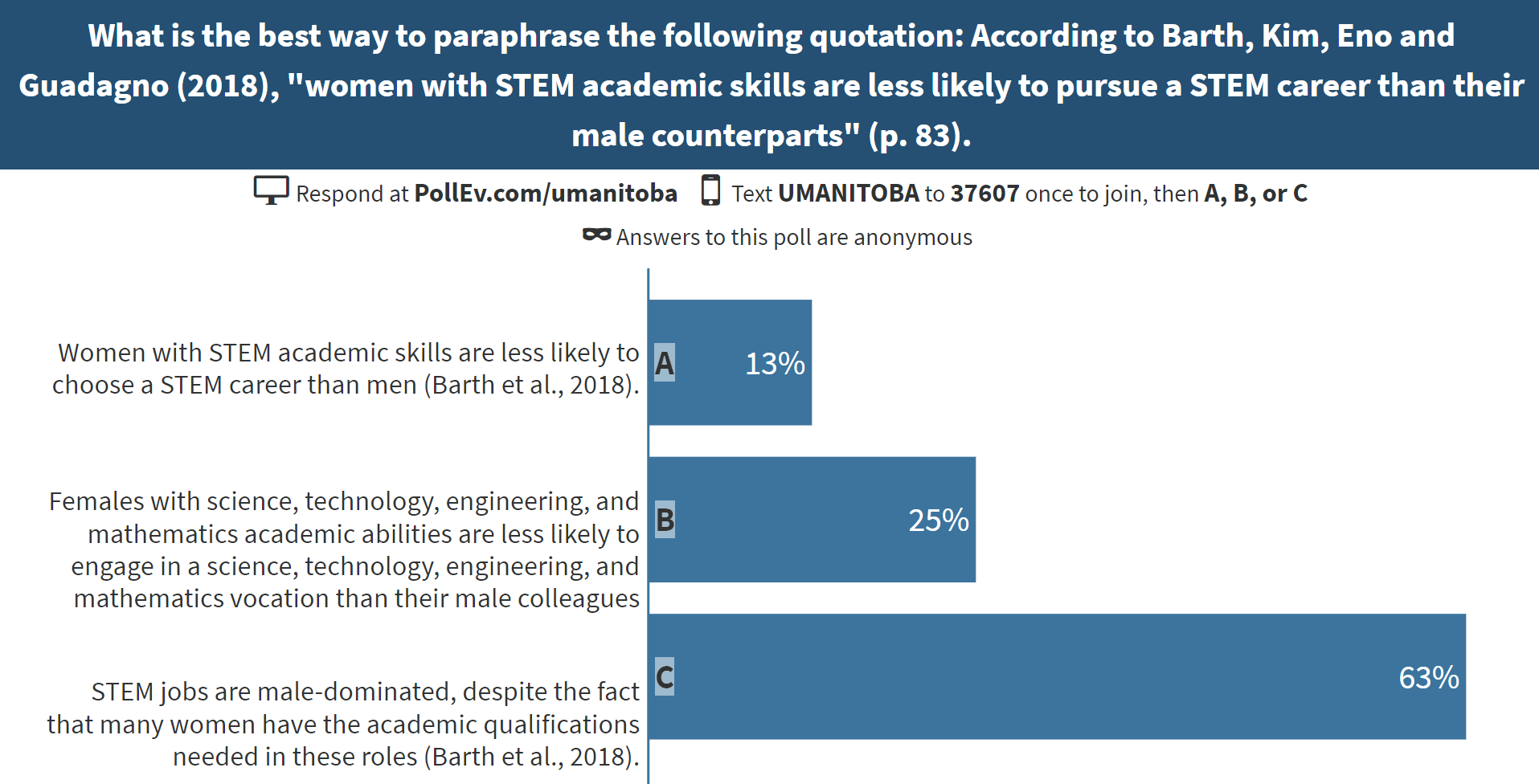

Critical reading, citation, and research

Activity: Create a series of citation examples using a polling tool, and encourage students to identify the option they would be most likely to use/recommend in a brief case study.

Trust and citation

Julian: "Is the bank open on Saturdays?"

Getting around the world means you have to trust people. The question is how much trust you should give and why. This depends on context.

Me: "Yes!"

Julian: "How do you know??"

Me: "I was there last year, I think."

Julian: "Do you actually know? If I don't make a payment, I'll lose my apartment"

Me: "Oh...I don't actually know. Let's check online."

Snow day

Julian: "Looks like a blizzard out. Are classes cancelled?"

Me: "Definitely!"

Julian: "How do you know??"

Me: "I looked out the window."

Me: "I checked the university homepage."

OR

I'M CITING SOMETHING

Citing as a "game"

- Expressing yourself meaningfully requires shared rules.

- This is like a board game/ sport. You can modify or disregard some rules, but there comes a point when you are no longer playing the original game.

3 important "moves" in the citation game

Following the citation game gives you some abilities by allowing for certain moves:

-

Duty/Obligation: 2-way obligation. If you take others' ideas seriously (by citing them), then people will take your ideas seriously.

-

Licence: Like a license to drive, but this is a license to put an idea forward/critique an idea. This license comes in different strengths. This strength is directly tied to the strength of the idea you are citing and how you explain it.

-

Legitimacy: How seriously people will take your claims depends on how well you use your licenses. The better (and more) connections you have to other ideas, the more likely people will take your ideas seriously.

Challenges of method

1. Requires more classroom time (and potentially more assignments/grading), and therefore, is dependent on instructors' support/trust.

2. The literature is not always supportive of scaffolding's effectiveness, especially in regards to research-specific tasks, which are rarely mentioned.

3. Some librarians may feel that certain aspects of instruction (i.e. discussing reading/note taking) falls outside of our roles/responsibilities.

Conclusion

-

By leveraging approaches that build off of social communication, HS can generate a strong feeling of community with both students and faculty.

-

HS develops critical knowledge of how information is generated contextually.

- Anecdotal observations indicate that students have a stronger understanding of when citations are required.

- HS illustrates that research involves more than simply finding information, but interacting with sources in a variety of ways.

- When teaching in this way, students are exposed to librarians' range of skills, and can more accurately understand our roles in instruction.

- For librarians, building these relationships helps generate the conditions for meaningful relationships, as well as allowing us to better anticipate student and faculty needs.

References

Brandom, R. (1994). Making it explicit: Reasoning, representing, and discursive commitment. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

Bratman, M. (2014). Shared agency: A planning theory of acting together. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Cortes-Vera, J., Garcia, T. J., & Gutierrez, A. (2017). Knowing and improving paraphrasing skills of Mexican college students. Information and Learning Science, 118(9/10), 490–502. https://doi.org/10.1108/ILS-05-2017-0042

Davidson, D. (2001). On the very notion of a conceptual scheme. In Inquiries into truth and interpretation (2nd ed., pp.183-198). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. (Original work published 1974). Brandom

Fricker, M. (2007). Epistemic injustice: power and the ethics of knowing. Oxford , UK: Oxford University Press.

Greer, K., Swanberg, S., Hristova, M., Switzer, A. T., Daniel, D., & Perdue, S. W. (2012). Beyond the web tutorial: Development and implementation of an online, self-directed academic integrity course at Oakland University. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 38(5), 251–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2012.06.010

MacMillan, M., & Rosenblatt, S. (2015). They’ve found it. Can they read it? Adding academic reading strategies to your IL toolkit. In D.M. Mueller (Ed.), ACRL 2015 Proceedings (pp. 757-762). Chicago, IL. Association of College and Research Libraries, a division of the American Library Association.

Martin, C. (2011) An information literacy perspective on learning and new media. On the Horizon, 19(4), 268-275. https://doi-org.uml.idm.oclc.org/10.1108/10748121111179394

Sellars, W. (1997). Empiricism and the philosophy of mind. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. (Original work published 1956).

Shvarts, A., & Bakker, A. (2019). The early history of the scaffolding metaphor: Bernstein, Luria, Vygotsky, and before. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/10749039.2019.1574306

Tomasello, M. (2014). A natural history of human thinking. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Tomasello, M. (2019). Becoming human: A theory of ontogeny. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wood, D., Bruner, J., & Ross, G. (1976). The role of tutoring in problem solving. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 17(2), 89–100. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1976.tb00381.x