MTRN4110 Python Workshop

by MTRNSoc

Code Repository

Topics Covered

- Variables and Types

- Strings

- Lists and Loops

- Tuples

- Functions

- Type Hints

- Dictionaries

- Numpy

What is Python?

- Interpreted

- Object-oriented

- Dynamic typing

- Garbage collected

- Scripting language

- Whitespace instead of { }

An interpreted language is where the source code is converted into bytecode which is then executed by a Python virtual machine.

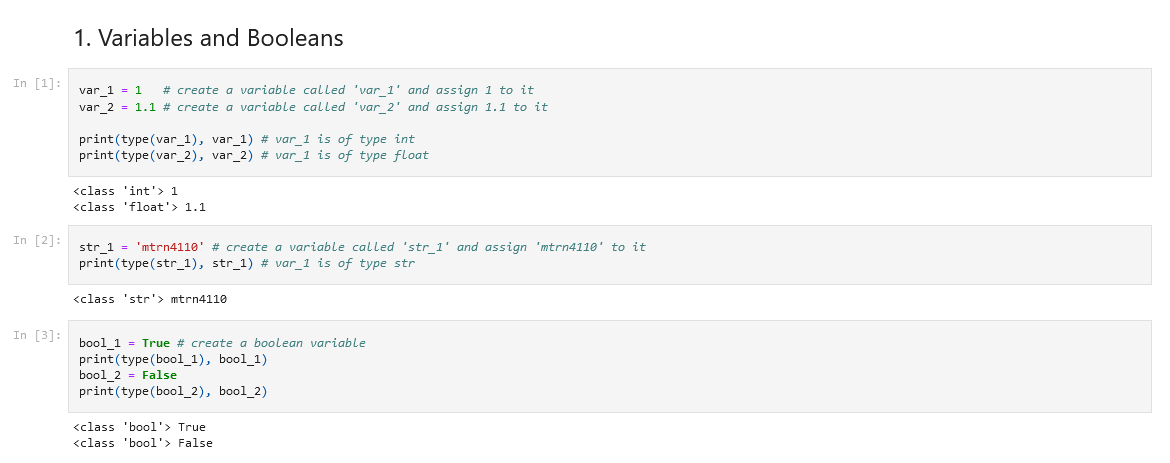

Variables and Types

Variables and Types

Python is dynamic typed, which means that its variables, parameters, and return values of a function is not specified at run-time

# 'a' is of type int

a = 1

print(type(a)) # <class 'int'>

# # 'b' is of type float

b = 1.0

print(type(b)) # <class 'float'>

# 'c' is of type str

c = "a"

print(type(c)) # <class 'str'>

# 'd' is of type str

d = 'mtrn4110'

print(type(d)) # <class 'str'>

# 'e' is of type bool

e = True

print(type(e)) # <class 'bool'>

Strings

Strings

name = "Giraffe"

age = 18

height = 2048.11 # mm

# Different ways of printing the same code

# Giraffe, 18, 2048.11

print(name + ", " + str(age) + ', ' + str(height)) # string concatenation

print(name, age, height, sep=', ')

print(f"{name}, {age}, {height}") # f-stringsStrings are immutable objects.

There are many different ways of formatting strings

String Methods

base = "Hi from mtrnsoc"

base_as_list = base.split(" ")

print(base_as_list)

# ['Hi', 'from', 'mtrnsoc']

print(base[0])

# H (first character)

print(base[-3])

# s (3rd last character)

# [start:stop:step]

# start: It is the index from where the slice starts. The default value is 0.

# stop: It is the index at which the slice stops.

# The character at this index is not included in the slice.

# The default value is the length of the string.

# step: It specifies the number of jumps to take while going from start to stop.

# It takes the default value of 1.

print(base[3:6:1])

# fro

There are also many types of in-built string methods that available to you

Conditions

Conditions

number = 42

if number == 42:

print("42 is the meaning of life")

elif number % 2 == 0:

print("Number is even")

else:

print("Number is odd")

if number == 42 and number % 2 == 0:

print("42 is the meaning of life")

print("number is also even")

if not number == 42:

print("Number is not 42")If statements are written slightly different in Python.

- Use `and` instead of &&

- Use `or` instead of ||

- Use `not` instead of !

Lists and Loops

Lists and Loops

names = ["Tanvee", "Alvin", "Juliet"]

names.append("Brandon")

print(names) # list is now ['Tanvee', 'Alvin', 'Juliet', 'Brandon']

for name in names:

print(name)

# This prints

# Tanvee

# Alvin

# Juliet

# Brandon

# Concatenating lists

names += ["Kyra", "Iniyan"]Lists are an ordered collection of data. They are very similar to vectors in C++. You can think of them as dynamically sized arrays.

Lists and Loops

names = ["Tanvee", "Alvin", "Juliet", "Kyra", "Iniyan"]

# Printing using indexes, like an array in c++

for i in range(0, len(names)):

print(names[i])

# Indexing is always dangerous, but if you need

# to know the index, this would be the better way

for index, name in enumerate(names):

print(f"{index} {name}")

# 0 Tanvee

# 1 Alvin

# 2 Juliet

# 3 Brandon

# 4 Kyra

# 5 IniyanYou can also loop through strings

Tuples

Tuples

- Tuples are used to store multiple items in a single variable.

- They are immutable (once created, you can't change values)

- To change it, you can convert the tuple to a list

- They are usually used when you have to return more than 1 value in a function

t = ('MTRNSoc', '2022')

print(t)

# ('MTRNSoc', '2022')

tList = list(t)

tList[-1] = '2023' # the index -1 accesses the last item

print(tList)

# ['MTRNSoc', '2023']Functions

Functions

- Functions in python don't have an explicit return type

- If you have a function definition with no content, use the pass keyword to avoid getting an error

def my_fun(x, y):

z = x + y

return z

# these types don't actually do anything

# when the code is run.

# Purely for IDEs/editors

def my_typed_fun(x: int, y: int) -> int:

z = x + y

return zDictionaries

Dictionaries

- Dictionaries are used to store data values in key:value pairs

- Unlike lists and arrays (C++) that are referenced by their integer index, dictionaries are referenced by their key that maps to a value.

- They are most similar to map and unordered_map in C++

Dictionaries

userData = {}

userData["name"] = "Leonard"

userData["age"] = 20

userData["height"] = "180cm"

print(userData)

# {'name': 'Leonard', 'age': 20, 'height': '180cm'}

# alternatively, you can construct a dictionary like this

userData2 = {

'name' : 'Janice',

'age' : 129,

'height' : '180cm'

}

print(userData2)

# {'name': 'Janice', 'age': 129, 'height': '180cm'}

randomDict = {

1: "hello",

2: "world"

}Dictionaries

Fetching Data using .get(). Takes in 1 argument and 1 optional argument.

- First argument: Key to look up

- Second argument: Default value if key was not found

userData = {

'name' : 'Janice',

'age' : 129,

'height' : '180cm'

}

print(userData.get("name"))

# janice

print(userData.get("zID", None))

# None (similar to null)Dictionaries

Looping through a dictionary

userData = {

'name' : 'Janice',

'age' : 129,

'height' : '180cm'

}

print(userData.items())

# dict_items([('name', 'Janice'), ('age', 129), ('height', '180cm')])

# List of tuples that we can destructure in the loop

for key, value in userData.items():

print(f"{key}: {value}")

# name: Janice

# age: 129

# height: 180cmType Hints

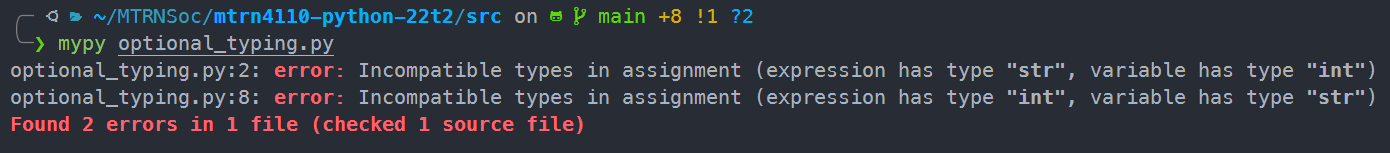

Type Hints

You can optionally write type hints in Python. These type hints don't actually do anything when you run the code. They are ignored by the python interpreter.

They are only used by code editors and by a type checker called "mypy"

number: int = 42

number = "hello" # should error

def add_numbers(a: int, b: int) -> int:

return a + b

some_string: str = "Hello World"

some_string = add_numbers(1, 2) # should error

Type Hints

Fancier type examples

import json

from typing import Dict, Optional, List, Union

numbers: List[Union[int, float]] = [1, 2.2, 3, 4, 5.0]

# List of numbers that can be int or float

class Packet:

"""The structure of packets for both receiver and sender"""

def __init__(self):

"""Initial data setup"""

self.flags: Dict[str, bool] = {

# Type describes a dictionary that maps strings -> booleans

"syn": False,

"ack": False,

"fin": False,

}

self.seq: Optional[int] = None

self.ack: Optional[int] = None

# Optional type as in the type can be None or an int

self.data = None

Modules

Modules

Each python file is its own module. A python file can import modules in order to re-use code

def add(x: int, y: int) -> int:

return x + yimport add

# import everything from add

from math_solvers import subtract, multiply

# This import is preferred as it only imports what

# it uses

print(add.add(1,2))

print(subtract(1,2))

print(multiply(1,2))def subtract(x: int, y: int) -> int:

return x - y

def multiply(x: int, y:int) -> int:

return x * yadd.py

math_solvers.py

calculators.py

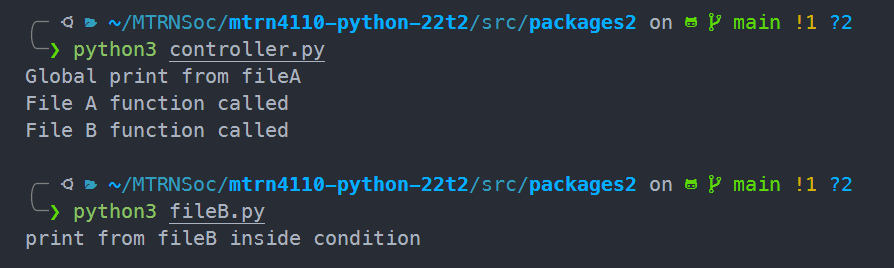

__name__

When code is imported from another python file/module, all global scoped code is run.

To prevent this, we have to wrap any globally scoped code inside this condition statement in fileB

def do_something_A():

print("File A function called")

print("Global print from fileA")def do_something_B():

print("File B function called")

if __name__ == "__main__":

# This statement is only ever true

# if fileB.py is directly run

print("print from fileB inside condition")import fileA

import fileB

fileA.do_something_A()

fileB.do_something_B()fileA.py

fileB.py

controller.py

pip3 packages

pip3 packages

One of python's greatest advantages compared to C++ is the easy availability of published packages.

These packages can be installed through something called pip3. Some examples of packages are:

- mypy: type checking

- numpy: scientific computing/maths

- scipy: math algorithms

- Flask: webserver

- pandas: data manipulation

- virtualenv: creating virtual environments

These packages can be installed by running the command:

pip3 install package_namevirtualenv

By default pip3 installs Python packages globally, virtualenv allows you to create an isolated Python environment where packages are installed in this isolated environment.

pip3 install virtualenvInstall the virtualenv package globally

Create a folder for the isolated Python environment

source venv/bin/activateUse the isolated python environment. This command would have to be done every time you open a new instance of a terminal

Requirements.txt

A requirements.txt is a file that exists that specifies what packages need to be installed in order to run the python code.

We can freeze and dump the packages we have currently installed into the txt file

pip3 install -r requirements.txtWe can install the packages based on the txt file

pip3 freeze > requirements.txtRequirements.txt

astroid==2.11.7

autopep8==1.6.0

dill==0.3.5.1

isort==5.10.1

lazy-object-proxy==1.7.1

mccabe==0.7.0

mypy==0.961

mypy-extensions==0.4.3

platformdirs==2.5.2

pycodestyle==2.8.0

pydocstyle==6.1.1

pylint==2.14.4

snowballstemmer==2.2.0

toml==0.10.2

tomli==2.0.1

tomlkit==0.11.1

typing_extensions==4.3.0

wrapt==1.14.1NumPy

NumPy

- It is a Python library used for working with multi-dimensional arrays and matrices

- Easy to use and feature packed

- Most of the algorithms are actually optimised C code

NumPy Arrays vs Lists

- NumPy arrays use significantly less memory especially in high dimensions

- Because most of the array functions execute from compiled C, they operate much faster

- Many packages use NumPy and have optimised algorithms built around arrays

- NumPy arrays cannot store different types in one array

NumPy Arrays

# import the library

import numpy as np

# Create array

list_2 = np.array([5, 2, 1, 8, 3, 4]) # create a one dimensional array list_2

print(type(list_2)) # print the type

print(list_2.shape) # print the shape of list_2

print(list_2[2]) # access third item

# Slicing and indexing

print(list_2[2:4:1]) # '2' is starting index, '4' is stopping index, '1' is the step

list_3 = np.array(([1, 2, 3], [3, 4, 5])) # create a two dimensional array list_3

print(list_3[1][2]) # print '5' import numpy as np

zero_array = np.zeros(2) # [0, 0]

one_array = np.ones(3) # [1, 1, 1]

empty_array = np.empty(4) # Not actually empty

r_array = np.arange(0, 10, 1) # [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10]

l_array = np.linspace(0, 10, 5) # [0, 2.5, 5, 7.5, 10]

Array Creation Methods

import numpy as np

arr = np.array([2, 1, 5, 3, 7, 4, 6, 8])

# Sorting an array (there are many sorting algos)

sorted_arr = np.sort(arr) # [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8]

# Concatenating arrays

np.concatenate((arr, sorted_array))

x = np.array([[1, 2], [3, 4]])

y = np.array([[5, 6]])

z = np.concatenate((x, y), axis=0)

# z = [[1, 2],

# [3, 4],

# [5, 6]]Array manipulation

Jupyter Notebooks

What is a Jupyter Notebook

- Jupyter notebooks are convenient way to write code for scientific or engineering use

- Notebooks contain both code and rich text elements

- They are aimed to be human readable documents that contain analysis description and execution

What is a Kernel?

- When a notebook runs a section of code, all the variables that are created are stored in memory

- Variables can be used across code segments

- The kernel manages the variables and python environment