COMP6771

Advanced C++ Programming

Week 5.1

Resource Management

In this lecture

Why?

- performance & control---> power vs great responsibility

- C++ responsibility and leak?

- automatic garbage collection to free heap?

- While we have ignored heap resources (malloc/free) to date, they are a critical part of many libraries and we need to understand best practices around usage.

What?

-

Resource can be very different

- Memory allocation, files, mutex, MPI communicator

- full control: create, manage and release: challenge for complex task

- manually ??

- new/delete

- copy and move semantics

- destructors

- lvalues and rvalues

Revision: Objects

-

What is an object in C++?

-

An object is a region of memory associated with a type

-

Unlike some other languages (Java), basic types such as int and bool are objects

-

-

For the most part, C++ objects are designed to be intuitive to use

-

What special things can we do with objects

-

Create

-

Destroy

-

Copy

-

Move

-

Long lifetimes

- There are 3 ways you can try and make an object in C++ have a lifetime that outlives the scope it was defined it:

- Returning it out of a function via copy (can have limitations)

- Returning it out of a function via references (bad, see slide below)

- Returning it out of a function as a heap resource (today's lecture)

//passing by reference with object

// created on heap

const Point& multiply(const Point& p){

Point *point=new Point();

//... Do multiplication

return *point;

}

//This function returns a new object,

// not a reference to the object

const Point multiply(const Point& p){

Point point();

//... Do multiplication

return point;

}//passing by reference with object

// created on stack

const Point& multiply(const Point& p){

Point point();

//... Do multiplication

return point;

}

Long lifetime with references

- We need to be very careful when returning references.

- The object must always outlive the reference.

- This is undefined behaviour - if you're unlucky, the code might even work!

- Moral of the story: Do not return references to variables local to the function returning.

- For objects we create INSIDE a function, we're going to have to create heap memory and return that.

auto okay(int& i) -> int& {

return i;

}

auto okay(int& i) -> int const& {

return i;

}auto not_okay(int i) -> int& {

return i;

}

auto not_okay() -> int& {

auto i = 0;

return i;

}New and delete

-

Objects are either stored on the stack or the heap

-

In general, most times you've been creating objects of a type it has been on the stack

-

We can create heap objects via new and free them via delete just like in C (malloc/free)

-

New and delete call the constructors/destructors of what they are creating

-

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

int main() {

int* a = new int{4};

std::vector<int>* b = new std::vector<int>{1,2,3};

std::cout << *a << "\n";

std::cout << (*b)[0] << "\n";

delete a;

delete b;

return 0;

}demo501-new.cpp

New and delete

-

Why do we need heap resources?

-

Heap object outlives the scope it was created in

-

More useful in contexts where we need more explicit control of ongoing memory size (e.g. vector as a dynamically sized array)

-

Stack has limited space on it for storage, heap is much larger

-

No matter how much we try, it is very difficult to free all dynamically allocated memory.

-

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

int* newInt(int i) {

int* a = new int{i};

return a;

}

int main() {

int* myInt = newInt();

std::cout << *a << "\n"; // a was defined in a scope that

// no longer exists

delete a;

return 0;

}demo502-scope.cpp

//No matter how much we try, it is very difficult

//to free all dynamically allocated memory.

void SomeMethod()

{

ClassA *a = new ClassA;

SomeOtherMethod(); // iwhat if t can throw an exception

delete a;

}std::vector<int> - under the hood

Let's speculate about how a vector is implemented. It's going to have to manage some form of heap memory, so maybe it looks like this? Is anything wrong with this?

class my_vec {

// Constructor

my_vec(int size): data_{new int[size]}, size_{size}, capacity_{size} {}

// Destructor

~my_vec() {};

int* data_;

int size_;

int capacity_;

}

Destructors

- Called when the object goes out of scope

- What might this be handy for?

- Does not occur for reference objects

- Implicitly noexcept

- What would the consequences be if this were not the case

- Why might destructors be handy?

- Freeing pointers

- Closing files

- Unlocking mutexes (from multithreading)

- Aborting database transactions

std::vector<int> - Destructors

- What happens when vec_short goes out of scope?

- Destructors are called on each member.

- Destructing a pointer type does nothing

- Destructors are called on each member.

- As it stands, this will result in a memory leak. How do we fix?

my_vec::~my_vec() {

delete[] data_;

}class my_vec {

// Constructor

my_vec(int size): data_{new int[size]}, size_{size}, capacity_{size} {}

// Destructor

~my_vec() {};

int* data_;

int size_;

int capacity_;

}Rule of 5

When writing a class, if we can't default all of our operators (preferred), we should consider the "rule of 5"

- Destructor

- Copy constructor

- Copy assignment

- Move assignment

- Move constructor

- The presence or absence of these 5 operations are critical in managing resources

- Ownership (single vs shared) and delegation power

- We only think how long we need recourse and manipulate object accordingly

std::vector<int> - under the hood

- Though you should always consider it, you should rarely have to write it

- If all data members have one of these defined, then the class should automatically define this for you

- But this may not always be what you want

- C++ follows the principle of "only pay for what you use"

- Zeroing out the data for an int is extra work

- Hence, moving an int actually just copies it

- Same for other basic types

class my_vec {

// Constructor

my_vec(int size): data_{new int[size]}, size_{size}, capacity_{size} {}

// Copy constructor

my_vec(my_vec const&) = default;

// Copy assignment

my_vec& operator=(my_vec const&) = default;

// Move constructor

my_vec(my_vec&&) noexcept = default;

// Move assignment

my_vec& operator=(my_vec&&) noexcept = default;

// Destructor

~my_vec() = default;

int* data_;

int size_;

int capacity_;

}// Call constructor.

auto vec_short = my_vec(2);

auto vec_long = my_vec(9);

// Doesn't do anything

auto& vec_ref = vec_long;

// Calls copy constructor.

auto vec_short2 = vec_short;

// Calls copy assignment.

vec_short2 = vec_long;

// Calls move constructor.

auto vec_long2 = std::move(vec_long);

// Calls move assignment

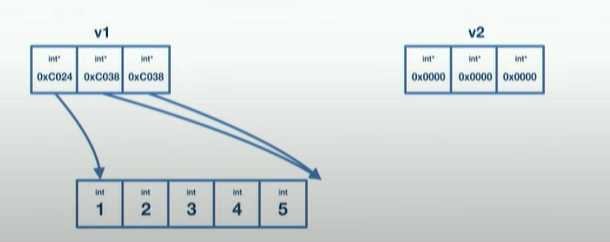

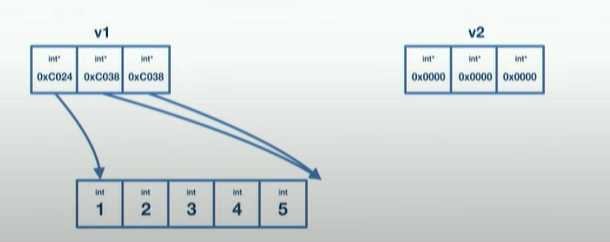

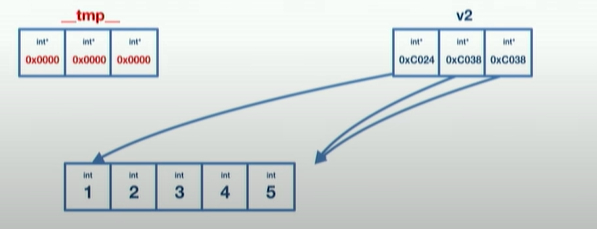

vec_long2 = std::move(vec_short);std::vector<int> - Copy constructor

- What does it mean to copy a my_vec?

- What does the default synthesized copy constructor do?

- It does a memberwise copy

- What are the consequences?

- Any modification to vec_short will also change vec_short2

- We will perform a double free

- How can we fix this?

class my_vec {

// Constructor

my_vec(int size):

data_{new int[size]},

size_{size},

capacity_{size} {}

// Copy constructor

my_vec(my_vec const&) = default;

// Copy assignment

my_vec& operator=(my_vec const&) = default;

// Move constructor

my_vec(my_vec&&) noexcept = default;

// Move assignment

my_vec& operator=(my_vec&&) noexcept = default;

// Destructor

~my_vec() = default;

int* data_;

int size_;

int capacity_;

}auto vec_short = my_vec(2);

auto vec_short2 = vec_short;

my_vec::my_vec(my_vec const& orig): data_{new int[orig.size_]},

size_{orig.size_},

capacity_{orig.size_} {

std::copy(orig.data_, orig.data_ + orig.size_, data_);

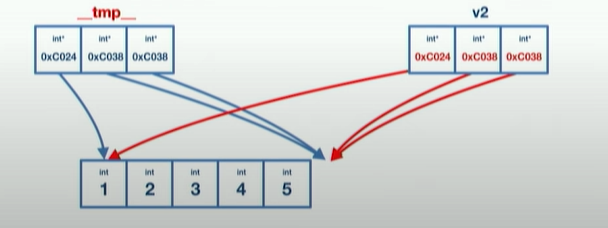

}std::vector<int> - Copy assignment

- Assignment is the same as construction, except that there is already a constructed object in your destination

- You need to clean up the destination first

- The copy-and-swap idiom makes this trivial

class my_vec {

// Constructor

my_vec(int size):

data_{new int[size]},

size_{size},

capacity_{size} {}

// Copy constructor

my_vec(my_vec const&) = default;

// Copy assignment

my_vec& operator=(my_vec const&) = default;

// Move constructor

my_vec(my_vec&&) noexcept = default;

// Move assignment

my_vec& operator=(my_vec&&) noexcept = default;

// Destructor

~my_vec() = default;

int* data_;

int size_;

int capacity_;

}auto vec_short = my_vec(2);

auto vec_long = my_vec(9);

vec_long = vec_short;

my_vec& my_vec::operator=(my_vec const& orig) {

my_vec(orig).swap(*this); return *this;

}

void my_vec::swap(my_vec& other) {

std::swap(data_, other.data_);

std::swap(size_, other.size_);

std::swap(capacity_, other.capacity_);

}

// Alternate implementation, may not be as performant.

my_vec& my_vec::operator=(my_vec const& orig) {

my_vec copy = orig;

std::swap(copy, *this);

return *this;

}

lvalue vs rvalue

- not really language features, properties of semantic

- STL advocated value semantic -> leads to freq. copying:

- Solution: rvalue copying-to take resources

-

lvalue: An expression that is an object reference

- E.G. Variable name, subscript reference

- Always has a defined address in memory

-

rvalue: Expression that is not an lvalue

- E.G. Object literals, return results of functions

- Generally has no storage associated with it

- rvalues are temporary and short lived, while lvalues live a longer life since they exist as variables

int main() {

int i = 5; // 5 is rvalue, i is lvalue

int j = i; // j is lvalue, i is lvalue

int k = 4 + i; // 4 + i produces rvalue then stored in lvalue k

int k = i + j; //ok

6=k; //error : error: lvalue required as left operand of assignment

int* y = &k; // lvalue=takes an lvalue argument and produces an rvalue

int* y = &666; // error: lvalue required as unary '&' operand

setValue() = 3; //rvalue= // lvalue required as left operand of

\\assignment: setValue() returns an rvalue

SeetValue() = 3; //Ok setGlobal returns a referenc lvalue

}int SeetValue()

{

return 6;

}

int& setValue()

{

return valuee;

}std::vector<std::vector<int> vec1;

std::vector<int> vec2={1,2,3,4,5};

//rvalue reference avoid copying

vec1.emplace_back(std::move(vec2));

C++11 std::cref // accept only lvalue reference

C++20 Rnages

auto rng=std::vector<int>{1,2,3} | std::view ..

.. ::filter([](int i){retrun 0==i%2;});lvalue references

- There are multiple types of references

- Lvalue references look like T&

- Lvalue references to const look like T const&

- Once the lvalue reference goes out of scope, it may still be needed

int y = 10;

int& yref = y;

yref++; //OK Ref must point to an existing object

int& yref = 10; // ??

void f(my_vec& x);

void f(int& x)

{

}

int main()

{

f(10); // Nope!

int x = 10;

f(x);

const int& ref = 10; // you are allowed to bind a const lvalue to an rvalue

++ref; // error: increment of read-only reference ‘ref

int* p2 = &f(); // error, cannot take the address of an rvalue

}const int& ref = 10;

// ... would translate to:

int __internal_unique_name = 10;

const int& ref = __internal_unique_name;rvalue references

- Rvalue references look like T&&

- rvalue references extend the lifespan of the temporary object to which they are assigned.

- Non-const rvalue references allow you to modify the rvalue.

- An rvalue reference formal parameter means that the value was disposable from the caller of the function

- If outer modified value, who would notice / care?

- The caller (main) has promised that it won't be used anymore

- If inner modified value, who would notice / care?

- The caller (outer) has never made such a promise.

- An rvalue reference parameter is an lvalue inside the function

- If outer modified value, who would notice / care?

// Declaring rvalue reference

int&& rref = 20;

void inner(std::string&& value) {

value[0] = 'H';

std::cout << value << '\n';

}

void outer(std::string&& value) {

inner(value); // This fails? Why?

std::cout << value << '\n';

}

int main() {

outer("hello"); // This works fine.

auto s = std::string("hello");

inner(s); // This fails because s is an lvalue.

} // as l-value cannot be assigned to the r-value references

int &&ref = a;std::move

// Looks something like this.

T&& move(T& value) {

return static_cast<T&&>(value);

}-

Uses of rvalue references:

- They are used in working with the move constructor and move assignment.

- cannot bind non-const lvalue reference of type ‘int&‘ to an rvalue of type ‘int’.

- cannot bind rvalue references of type ‘int&&‘ to lvalue of type ‘int’.

- A library function that converts an lvalue to an rvalue so that a "move constructor" (similar to copy constructor) can use it.

- This says "I don't care about this anymore"

- All this does is allow the compiler to use rvalue reference overloads

void inner(std::string&& value) {

value[0] = 'H';

std::cout << value << '\n';

}

void outer(std::string&& value) {

inner(std::move(value));

// Value is now in a valid but unspecified state.

// Although this isn't a compiler error, this is bad code.

// Don't access variables that were moved from, except to reconstruct them.

std::cout << value << '\n';

}

int main() {

f1("hello"); // This works fine.

auto s = std::string("hello");

f2(s); // This fails because i is an lvalue.

}void fun(X& x); // lvalue reference overload

void fun(X&& x); // rvalue reference overload

fun(a);

fun(100);void fun(int& value){

std::cout<<"lvalue";

}

void fun(const int& value){

std::cout<<"Constant lvalue";

}

void fun(int&& value){

std::cout<<"rvalue";

}

int main(){

int value=5;

fun(value);

fun(5);

fun(std::move(value));

fun(static_cast<int &&>(value));

}Moving objects

- Always declare your moves as noexcept

- Failing to do so can make your code slower

- Consider: push_back in a vector

- Unless otherwise specified, objects that have been moved from are in a valid but unspecified state

- Moving is an optimisation on copying

- The only difference is that when moving, the moved-from object is mutable

- Not all types can take advantage of this

- If moving an int, mutating the moved-from int is extra work

- If moving a vector, mutating the moved-from vector potentially saves a lot of work

- Moved from objects must be placed in a valid state

- Moved-from containers usually contain the default-constructed value

- Moved-from types that are cheap to copy are usually unmodified

- Although this is the only requirement, individual types may add their own constraints

- Compiler-generated move constructor / assignment performs memberwise moves

std::vector<int> - Move constructor

class my_vec {

// Constructor

my_vec(int size)

: data_{new int[size]}

, size_{size}

, capacity_{size} {}

// Copy constructor

my_vec(my_vec const&) = default;

// Copy assignment

my_vec& operator=(my_vec const&) = default;

// Move constructor

my_vec(my_vec&&) noexcept = default;

// Move assignment

my_vec& operator=(my_vec&&) noexcept = default;

// Destructor

~my_vec() = default;

int* data_;

int size_;

int capacity_;

}auto vec_short = my_vec(2);

auto vec_short2 = std::move(vec_short);

my_vec::my_vec(my_vec&& orig) noexcept

: data_{std::exchange(orig.data_, nullptr)}

, size_{std::exchange(orig.size_, 0)}

, capacity_{std::exchange(orig.capacity_, 0)} {}Very similar to copy constructor, except we can use std::exchange instead.

std::vector<int> - Move assignment

Like the move constructor, but the destination is already constructed

class my_vec {

// Constructor

my_vec(int size): data_{new int[size]}, size_{size}, capacity_{size} {}

// Copy constructor

my_vec(my_vec const&) = default;

// Copy assignment

my_vec& operator=(my_vec const&) = default;

// Move constructor

my_vec(my_vec&&) noexcept = default;

// Move assignment

my_vec& operator=(my_vec&&) noexcept = default;

// Destructor

~my_vec() = default;

int* data_;

int size_;

int capacity_;

}auto vec_short = my_vec(2);

auto vec_long = my_vec(9);

vec_long = std::move(vec_short);

my_vec& my_vec::operator=(my_vec&& orig) noexcept {

// The easiest way to write a move assignment is generally to do

// memberwise swaps, then clean up the orig object.

// Doing so may mean some redundant code, but it means you don't

// need to deal with mixed state between objects.

std::swap(data_, orig.data_);

std::swap(size_, orig.size_);

std::swap(capacity_, orig.capacity_);

// The following line may or may not be nessecary, depending on

// if you decide to add additional constraints to your moved-from object.

delete[] orig.data_

orig.data_ = nullptr;

orig.size_ = 0;

orig.capacity = 0;

return *this;

}Explicitly deleted copies and moves

- We may not want a type to be copyable / moveable

- If so, we can declare fn() = delete

class T {

T(const T&) = delete;

T(T&&) = delete;

T& operator=(const T&) = delete;

T& operator=(T&&) = delete;

};Implicitly deleted copies and moves

- Under certain conditions, the compiler will not generate copies and moves

- The implicitly defined copy constructor calls the copy constructor member-wise

- If one of its members doesn't have a copy constructor, the compiler can't generate one for you

- Same applies for copy assignment, move constructor, and move assignment

- Under certain conditions, the compiler will not automatically generate copy / move assignment / constructors

- eg. If you have manually defined a destructor, the copy constructor isn't generated

- If you define one of the rule of five, you should explictly delete, default, or define all five

- If the default behaviour isn't sufficient for one of them, it likely isn't sufficient for others

- Explicitly doing this tells the reader of your code that you have carefully considered this

- This also means you don't need to remember all of the rules about "if I write X, then is Y generated"

RAII (Resource Acquisition Is Initialization)

In summary, today is really about emphasising RAII

-

Resource = heap object

-

A concept where we encapsulate resources inside objects

- Acquire the resource in the constructor

- Release the resource in the destructor

-

eg. Memory, locks, files

-

resource is always released at a known point in the program, which you can control.

-

Every resource should be owned by either:

-

Another resource (eg. smart pointer, data member)

-

Named resource on the stack

-

A nameless temporary variable

-

Object lifetimes

To create safe object lifetimes in C++, we always attach the lifetime of one object to that of something else

-

Named objects:

- A variable in a function is tied to its scope

- A data member is tied to the lifetime of the class instance

- An element in a std::vector is tied to the lifetime of the vector

-

Unnamed objects:

- A heap object should be tied to the lifetime of whatever object created it

-

Examples of bad programming practice

- An owning raw pointer is tied to nothing

- A C-style array is tied to nothing

- Strongly recommend watching the first 44 minutes of Herb Sutter's cppcon talk "Leak freedom in C++... By Default"

class widget {

private:

gadget g; // lifetime automatically tied to enclosing object

public:

void draw();

};

void functionUsingWidget () {

widget w; // lifetime automatically tied to enclosing scope

// constructs w, including the w.g gadget member

// ...

w.draw();

// ...

} // automatic destruction and deallocation for w and w.g

// automatic exception safety,

// as if "finally { w.dispose(); w.g.dispose(); }"class widget

{

private:

int* data;

public:

widget(const int size) { data = new int[size]; } // acquire

~widget() { delete[] data; } // release

void do_something() {}

};

void functionUsingWidget() {

widget w(1000000); // lifetime automatically tied to enclosing scope

// constructs w, including the w.data member

w.do_something();

} // automatic destruction and deallocation for w and w.data#include <memory>

class widget

{

private:

std::unique_ptr<int[]> data;

public:

widget(const int size) { data = std::make_unique<int[]>(size); }

void do_something() {}

};

void functionUsingWidget() {

widget w(1000000); // lifetime automatically tied to enclosing scope

// constructs w, including the w.data gadget member

// ...

w.do_something();

// ...

} // automatic destruction and deallocation for w and w.datavoid SomeMethod()

{

ClassA *a = new ClassA;

SomeOtherMethod(); // it can throw an exception

delete a;

}void SomeMethod()

{

std::auto_ptr<ClassA> a(new ClassA); // deprecated, please check the text

SomeOtherMethod(); // it can throw an exception

}

//Using smart pointers for memory allocation, we may be eliminate the

// potential for memory leaks. Feedback