Emergence of Jewish Religion

Premise

Analyzing the general framework of monotheism and its historical development (macro-analysis) equips us with a framework within which to analyze the ideologies and patterns of particular monotheistic groups (historical and modern; micro-analysis).

We will often emphasize fundamental and extremist movements because of their literal interpretations of text and theology.

- To a certain degree, the extreme ends of any philosophy or ideology shape the normative discourse and attitudes of the moderate center.

Background History on Israelite History and Religion

Political Background: Confederacy

- It is likely that different tribes worshiped different deities.

- Yahweh was the god of the confederacy of tribes ("Israel" in the texts) against enemies in times of conflict (cf. Josh 24).

- Yahweh took on the role of a shared symbol of collective desire

- "Israel" = multivalent term:

- Denotes northern kingdom in contrast to the southern kingdom of Judah

- Adopted by southern authors to refer to Judah

- Adopted by returning exiles as the identification of a restored nation/kingdom

Religious-Cultural Background

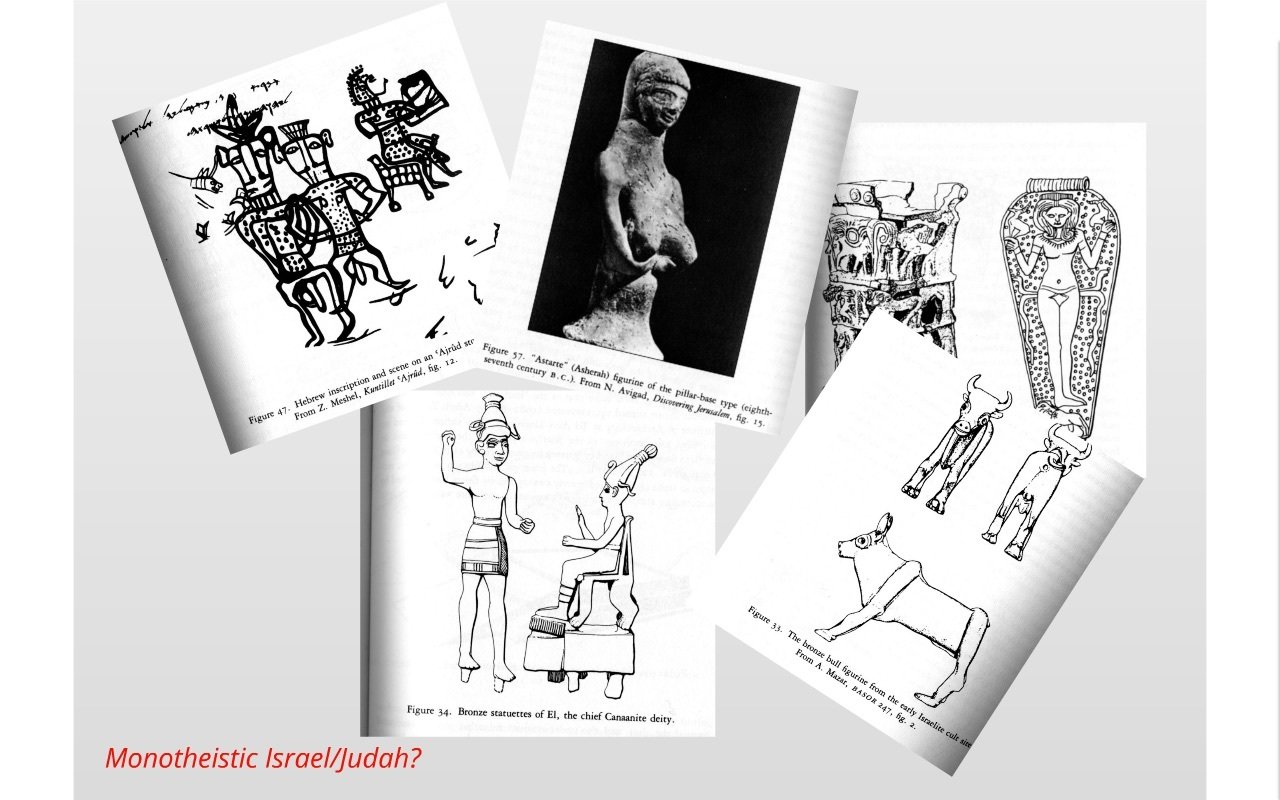

- Despite popular perception, Israel was not always monotheistic.

- Strict monotheism doesn't emerge until during the 6th century B.C.E. and later.

- Most of the biblical authors pre-6th century accepted the existence of other deities (tended to be henotheistic).

- An emphasis upon a centralized cultural-religious identity accompanied the need for political centralization.

- Initially, Yahweh was the politlical god, the god of the monarchy and so also of the kingdom.

- In the wake of exile, concerns for preserving identity and reclaiming political authority encouraged a more exclusivist attitude.

Chronology

Interpreting the Exile

Responses dealt with political concerns

- Dtr. maintained that the exiles were punishments from God for disobedience.

- The prophets (for which we have record) largely supported this view.

- Ezra-Nehemiah (EN) reinforces boundaries to distinguish between insider and outsider.

- EN interprets the "disobedience of Israel" as a consequence of assimilation.

- In the absence of an internal political law, EN centralizes the "law" as a shared symbol around which the community should organize itself.

- Obedience to religious law is equated with ethical social-political norm.

- Intermarriage is strictly forbidden (= rewriting the social-political identity of the "citizen").

Emergence of Monotheism

The loss and subsequent desire for "national" identity, including a political authority and land as tangible confirmation, provided the catalyst for the unifying and absolute "language" of the monotheistic identity of the Judean returnees. It was unifying because it sought to establish clear, communal (and presumably social and political) boundaries in a relatively chaotic and ambiguous context. It invoked notions of the absolute in order to articulate its own distinction and claim to the land and authority above the other competitors. The language of empire facilitated this strategy. Yahweh was promoted from national god to god whose power extended over the known world and beyond immediate political boundaries.

Early monotheistic identity in Judah was a result of imperial conquest and a "return" of exiled Judeans, who redefined Judean political identity in terms of their own experiences.

So...

- Monotheism did not "evolve" in Israel. Israel was heno-/polytheistic until after the exiles.

- Archaeological evidence supports a decline in deities worshipped.

- "Yahweh" became the symbol of collective desire. Yahweh was exclusive because that desire was exclusive.

- The early monotheistic community was less concerned about religion for the sake of religion and more about establishing a stabilized world.

Ezra-Nehemiah's prohibition on intermarriage reflected a deep concern for establishing and regulating community boundaries (cf. Neh. 13:23-27).

Example:

The "law" in Ezra-Nehemiah was intended to fashion (note constructivist and not descriptive) the social-political order into one consistent with golah collective desire for land and authority.

Fundamentals of Monotheism

Three pillars of monotheism:

- Revelation

- Law

- Restoration

Concepts of an exclusive God did not produce a monotheistic religion. The desire for exclusive authority and control over the land produced the idea of an exclusive God.

- God symbolized collective identity and desire for land and authority (and stability/nomos)

- The actions and and attributes of God reflect those of the community (note for instance, the Mosaic Covenant, the Exodus tradition, Passover, etc.)