Engineering design methods

Introduction

-

FIRST Senior Mentor

-

Over 1500 hours of FRC experience

-

Ran a team in 2014

-

Made a lot of mistakes

Your goals

Will address them at the end

This presentation

- Because it's me, going to be team-centric

- Ask questions at any time

- Going over

- Principles of design

- Iteration

- The process of creating

- FRC design components

- Could be long or short depending on interruptions

What is engineering?

The job

- Design and development

- Testing and verifying results

- Creation and building

- Solve problems

The effects

- New products

- Improvements of old designs

- Solve different problems with existing solutions

- Solve same problems with different solutions

The process

- Scientific and rigid

- Open to improvement

- Constantly changing and evolving

Why?

The three FRC principles

Simple

Consistent

Effective

Goal

Design

Results

Prototype

Building

Testing

Engineering

Analysis

Simple

What makes a design simple?

Evaluating simplicity

- Is the task completed?

- Is the solution complex?

- How many elements are involved in completing the goal?

- Is everything necessary to complete the strategic goal?

Examples

- Completing two tasks with one mechanism

- Using less parts, weight or power

- Wheels - mechanum, omni, traction, etc.

- Moving mechanism vs. static

- Going out of perimeter

- Endgame - do it or not?

Remarkably simple

Team 67 in 2012 is a perfect example of the balance between simplicity and being effective.

- Intake

- Index

- Bridge balancing

- Middle barrier

- Ground intake

- Pushes bridge

Effective

Effective

-

Some strategies take away potential

-

1 pointers in most games

-

-

Some strategies are 100% effective - no points are lost

-

Some strategies aren’t used commonly - opens opportunities to be most effective

-

Opposite is true too - popular strategies “steal” each other’s potential

-

Effective

Being effective is a combination of:

- Timing

- Scoring

- Defence

- "Stealing" points

You can think of your design as having a +/- value, being worth a certain amount of points per game.

Questions about effectiveness

- Does the design provide value to an alliance?

- How quickly do you score / defend?

- What could stop your design from working?

- High risk vs. low risk?

Prototypes don't lie

Do not fall for the "we'll get it working better later"

Prototypes are there for a reason!

Consistent

Consistency tropes all else

- Combination of simplicity, efficiency and ruggedness

- Remember that you'll only run for <100 hours

- Concentrate on pinch points, moving systems, and hard-to-repair components

- Design for breakage - make things accessable

Questions for a consistent design

- Does your design work consistently on your prototype?

- Can you replicate the machine / mechanism easily?

- What has worked consistently for other teams?

- What is everyone else doing? Why?

Tips for consistency

- Pneumatics? Default is no.

- West coast drive if at all possible

- Electronics done right the first time

- Measure twice, cut once

- Make backup parts

- Design with a constant worry of breaking

- In other words, overdesign

- Keep it simple, stupid!

Avoid

- Banebot / fisher price motors

- Omnidirectional drivetrains

- More than 2 functional mechanisms

- Goals that require more than 2 mini-CIMs

- Uncontrolled stored energy

The iterative process

How to iterate

- Brainstorm

- Design

- Prototype

- Test

- Improve

- Back to step 1

Iteration within a timeline

- Hard to do scientifically

- Lots of gut feelings

- Key is staying logical, consistent and fair

- Simple should always win, given no other variables

- Set goals ahead of time

Outline your goals

- What does the design need to accomplish?

- How quickly should it do the task?

- How many times does it need to do the task?

- What are possible "backup goals"?

- What is high priority for you?

Errors

- Failures are just as important as successes!

- Your worst prototypes give you the best lessons

- Try everything once, but don't over-think

- Everything is a data point, including other teams

Brainstorming

Getting from a goal to a solution

Design & Brainstorming

For most people, this comes naturally.

Well, not really. Smart ideas start as "obvious" ones.

Countless examples of teams - consistently the most obvious solutions are ignored because they don't feel "clever" enough.

Iterate on the obvious ideas, don't purposely go outside the box.

Research and testing

Research

Other teams are your best resource during build season

- Chief Delphi

- Twitter, facebook, etc.

- Robot in 3 Days

Look at industry solutions and bring them to simple ideas. (ie. 2012 tennis ball thrower VS. basketball shooter)

Testing

- Be scientific

- Record all possible data, including video, distances, times, speed, any physical data about the test

- Don't give up before going through all configurations for the device

- Vary your environment - try and replicate game situations

- Take in consideration the game (ie. blockers?)

Prototyping

- Use your fabrication team well

- Go with the most basic solutions that still prove an idea

- Use wood, lego - anything that requires little time to set up and change

- Allow for adjustments - you want to change things about your design sooner or later

- Start building ASAP, no matter where your strategy discussions are going

- Keep budget in mind, but push your prototypes to their limit (how many designs can you think of)

- Groups of 2-3 in charge of each design

Decision making

Timing

Be clear about when design decisions will be made. The people who want to be heard need to be there prior to that time.

Once you've decided, do not go back.

- One exception is just removing the mechanism

Design should always be done before week 3.

Task Management

- Who is prototyping?

- Who is making design decisions?

- Who is testing prototypes?

- Who is analysing information and iterating designs?

- Who sets goals for designs?

- Who takes charge of putting everything together in the design?

- Who answers the above questions?

Engineering decisions

Each team must have a defined way to make your design decisions.

As always, every team is unique.

My experience:

- Best decisions have been 2-3 people taking the final word

- 1 person doing everything doesn't work

- "Democracy" gives you a below average offence, every single time

Break

FRC Design

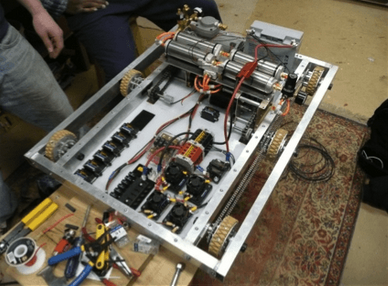

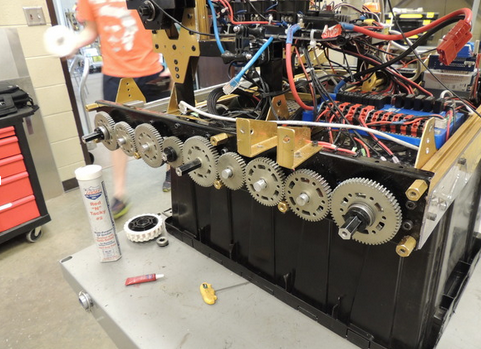

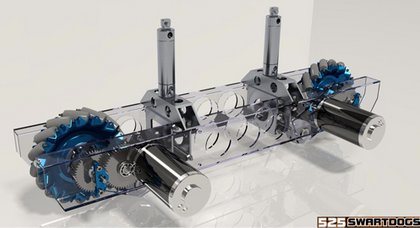

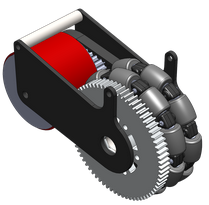

Gearboxes

-

Transmit power from the motors to the drive shafts.

-

It is important to choose a gearbox with the right gear ratio for the setup you are using (wheel size, sprocket gearing, number of motors, etc).

-

Three main decisions to make when choosing gearboxes: custom vs. stock, high speed vs. low speed, and one speed or shifters.

-

Off The Shelf

-

Ready to go - no time spent troubleshooting.

-

Very specific options available.

-

May have to modify designs to work with stock gearboxes.

-

-

Custom

-

Design and labor intensive.

-

Can be made to work with design - easier to access, install, maintain, replace, etc.

-

The “pro” option.

-

-

High Speed

-

More maneuverable, less time to traverse field, harder to block.

-

High speed = minimal torque = minimal pushing power.

-

-

Low Speed

-

Pushing power.

-

-

One Speed

-

Simple. Very little maintenance required.

-

Have to choose - either fast or slow.

-

-

Shifter

-

Multi-speed pneumatic operated transmission allows for comfortable motor RPM ranges at different speeds.

-

Custom shifters are difficult; if you choose shifters, off the shelf/modified will likely will be be your best choice.

-

Can be both fast and pushy.

-

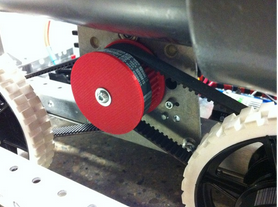

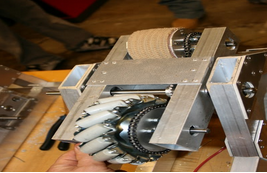

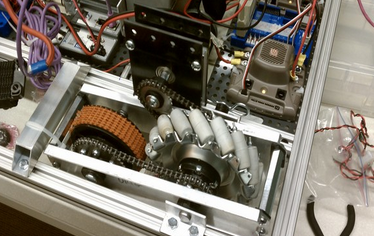

Power Transmission

There are three options for power transmission, being belts, chains, or gears.

Belts

-

Lightweight

-

Durable

-

Not adjustable

- Requires very little maintenance.

Chains

-

Perhaps the easiest option.

-

Maintenance intensive - tensioning as they stretch, grease, etc.

-

Not always accurate - you need to remove two links when you remove one.

- Two sizes common in FRC: Number 25 and Number 35.

Gears

-

Some teams decide to go with an entirely geared setup.

-

Requires minimal maintenance.

-

Requires most know-how to build.

-

Slightly heavier than belts, about the same as chains.

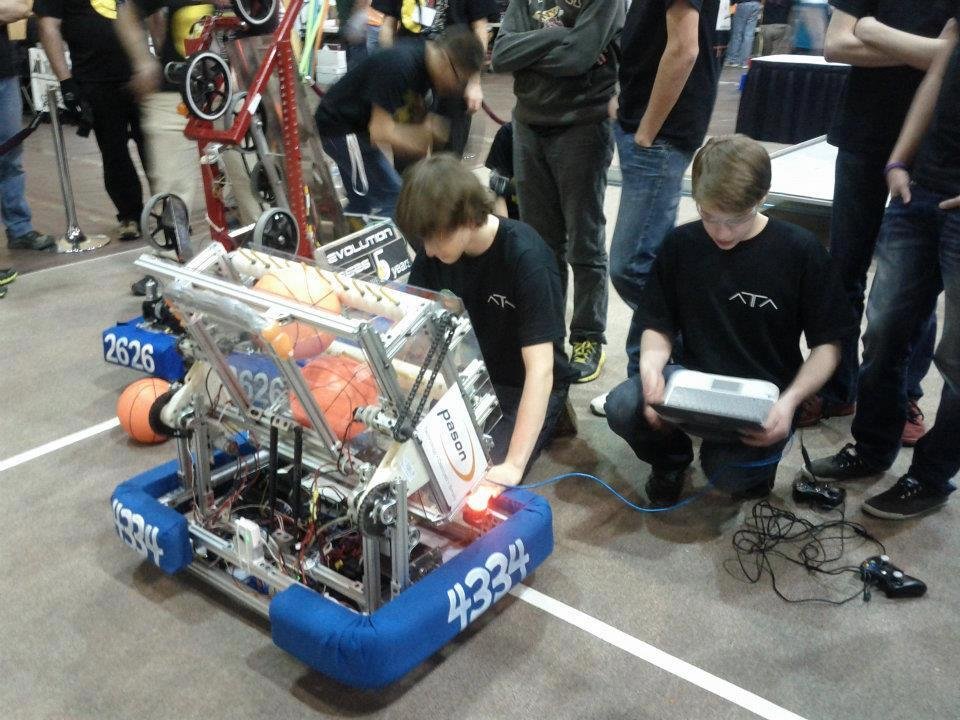

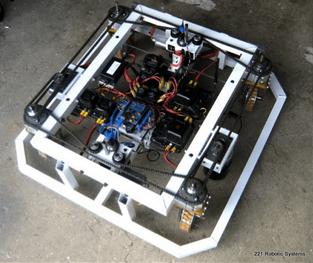

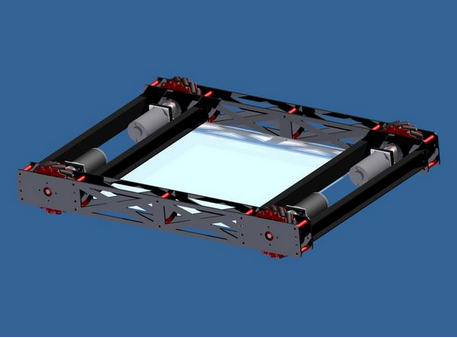

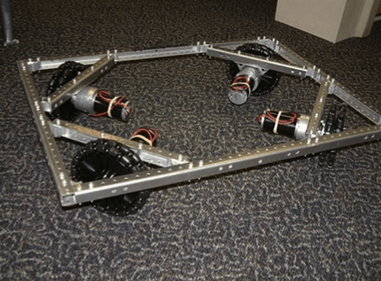

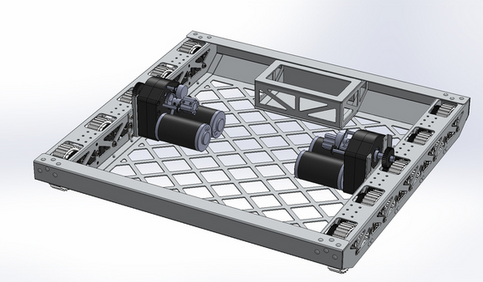

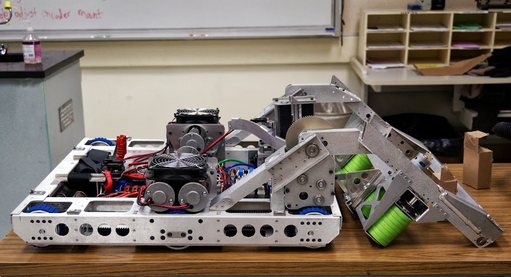

Drivetrains

Drivetrains are the base of any robot.

They are the wheels, motors, and metal that allow the robot to move around the field.

There are drivetrains that allow for omnidirectional movement at a cost of complication and pushing power.

Types of drivetrain

- Swerve

- Mecanum

- Holonomic

- Butterfly

- Tank

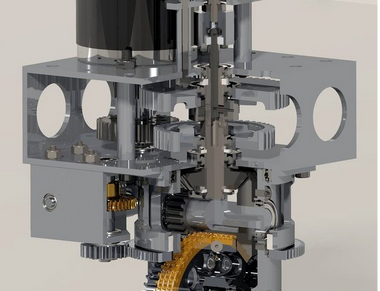

Swerve Drive

Potential for high speed and

pushing force.

Agile

Very complex.

Extra motors required for

manoeuvring.

Difficult to program and drive.

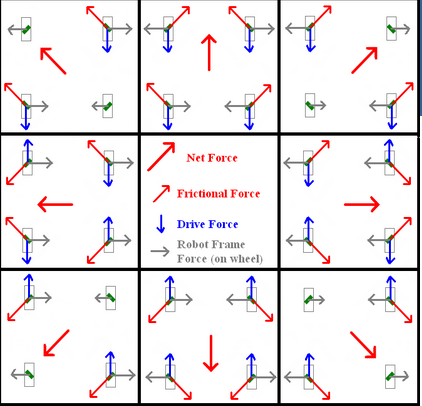

Mecanum Drive

Fairly easy to design and build.

Agile (if implemented correctly).

No potential for high pushing force.

Requires one gearbox per wheel.

Wheels are expensive.

Holonomic (Omni) Drive

Agile

Can be configured in a wide variety of ways.

Requires one gearbox per wheel.

Difficult to drive and program well.

No potential for significant pushing force.

Butterfly Drive

Can switch wheel in contact with floor using pneumatic cylinder.

Allows for omnidirectional movement as well as pushing power when needed.

Complicated. Really complicated.

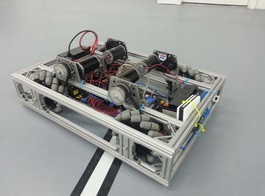

Tank Drive

Easiest drive

Can be configured in 6, 8, and 10 wheel variations.

Steers like a tank by controlling the wheels of each side independently.

Movement systems

Motors

- Consistent and proven

- Hard to overwhelm

- Good for any rotation of general movement in a direction

- Usually the least expensive option

- May be difficult to incorporate for some solutions

- See pneumatics and linear motion

- Versatile, and should be your default thinking pattern

Linear Motion

Need to move something linearly?

- Rare in FRC because of motor solutions

- Elevators are usually the only good implementation

- Requires specific equipment

- Low maintenance, good power (usually)

Pneumatics

Pneumatics has pros and cons

- Good for moving between two positions

- ex. ground loaders

- Bad because it adds a lot of complexity to electronics

- Only use when more than 3 subsystems require it

- Expensive! Especially starting out

Small movements

Options are:

- Servos

- ???

Essentially, if you need something small to happen, FRC is a bad place to do so

Look at smaller robotic parts (PM hobbycraft is great)

Power

When you just need pure torque or lifting power:

- Geared motor

- Pneumatics

- Servos, etc.

Motors are great because you can always extend torque to crazy proportions. You'll never be limited by a CIM or BAG motor.

Software as a design decision

Software

Software is underrated as a key component of design

Outline in advance:

What the robot will do

How it will do that

What and how software will make that easier

What kind of autonomous modes it will have

How safeties will be implemented

Advantages of software

More scoring in autonomous

Consistency and avoiding breakage

Consistent uptime

Uncovered features and aspects of strategy

Other design considerations

Interactions

- Seen it way too often - subsystems literally collide because nobody made sure they wouldn't

- Generally try and make sure your subsystems work well together

- ex. loader and index

- ex. shooter and index

Do your electronics get interference from the physical components of the robot?

Flow of systems

How does the game object move through your robot (if it does) ?

As mentioned before, ensuring nothing conflicts which another subsystem

Design with the entirety of the robot in mind! Never prototype without that consideration.

Break

Design Activity

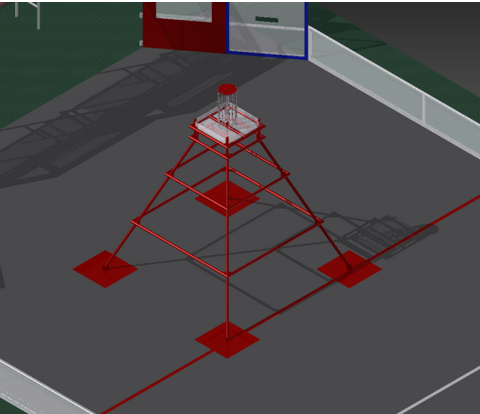

The 2013 Pyramid

Your Objective

Climb all three levels

Less than 30 seconds

Your Goal

Simple explanation of mechanism

3 different prototype ideas

Ways to iterate that design

Example Robot Designs

“The best designers sometimes disregard the principles of design. When they do so, however, there is usually some compensating merit attained at the cost of the violation. Unless you are certain of doing as well, it is best to abide by the principles.”

- William Lidwell, Author of Universal Principles of Design

Principles

Unity

All elements of the design work together

Cohesive flow

Balance

Components fill the holes of other elements

Ex. Floor loader & Shooter

Dominance/emphasis

Main elements should be obvious

Functionality is naturally dominant part of design