INTRO TO CPSC 310

Jordan Chiu + Sasha Avreline

January 2020

Before we start:

- Install Node.js --> https://nodejs.org/en/

- Install yarn --> https://yarnpkg.com/en/docs/install

- Open a TS compiler --> https://repl.it/languages/typescript

Welcome!

If you haven't already:

- Install Node.js --> https://nodejs.org/en/

- Install yarn --> https://yarnpkg.com/en/docs/install

- Open a TS compiler --> https://repl.it/languages/typescript

We're going to go through A LOT of material today; it won't all click right away.

When you see purple, that means it's an interactive demo/exercise.

Take some time and go over these slides later!

-

Java TO TypeScript

-

Node / Yarn

-

Async

-

Java TO TypeScript

-

Node / Yarn

-

Async

Java

TypeScript

// Types

boolean userMan = true;

int userAge = 81;

float userAverage = 10.5;

String userName = "Henri Bergson";

// Methods

public int multiply(int a, int b) {

return a * b;

}

// Classes

public class User {

public String firstName;

public User(String firstName) {

this.firstName = firstName;

}

public void sayHello() {

System.out.println("Hello!");

}

}

User myUser = new User("Henri");

myUser.firstName;

myUser.sayHello();// Types

let userMan: boolean = true;

let userAge: number = 81;

let userAverage: number = 10.5;

let userName: string = "Henri Bergson";

// Methods

function multiply(a: number, b: number): number {

return a * b;

}

// Classes

class User {

public firstName: string;

public constructor(firstName: string) {

this.firstName = firstName;

}

public sayHello(): void {

console.log("Hello!");

}

}

let myUser: User = new User("Henri");

myUser.firstName;

myUser.sayHello();The Basics

// Boolean

let isDone: boolean = false;

// Number

let decimal: number = 6;

let floating: number = 3.14159;

// String

let color: string = "blue";

color = 'red';

// Array

let list: number[] = [1, 2, 3];

// Any

let notSure: any = 4;

notSure = "maybe a string instead";

notSure = false; // okay, definitely a boolean

let list: any[] = [1, true, "free"];

// Null and undefined

let u: undefined = undefined;

let n: null = null;

// Object

// object is a type that represents the non-primitive type,

// i.e. anything that is not number, string, boolean, bigint, symbol, null, or undefined

let obj: { x: number, y: number };

obj = { x: 10, y: 20 };

// If in doubt, check the type!

console.log(typeof obj);Typescript: Types

TYPESCRIPT: == VS. ===

Short version:

- Always use ===

- Never use ==

TYPESCRIPT: == VS. ===

let a = 10;

a == 10 // true

a === 10 // true

a == '10' // true (???)

a === '10' // false :D

null == undefined // true (???)

null === undefined // false :DShort version:

- Always use ===

- Never use ==

Medium version

- ECMAScript, the standard for JavaScript (and TypeScript) does weird things with == that you wouldn't expect it to:

The comparison x === y with equals operator, where x and y are values, produces true or false only when...

- types of x and y are same

- values of x and y are equal

TYPESCRIPT: == VS. ===

Long version:

Read the ECMAScript Specification for yourself here -->

for(let i=0;i<10;i++) {

console.log(i); // i is visible thus is logged in the console as 0,1,2,....,9

}

console.log(i); // throws an error as "i is not defined" because i is not visibleTypescript: "LET" vs. "VAR"

let and var are both keywords you use to declare variables

- var variables are scoped to the immediate function body (function scope).

for(var i=0; i<10; i++){

console.log(i); // i is visible thus is logged in the console as 0,1,2,....,9

}

console.log(i); // i is visible here too. thus is logged as 10.

// Why? Because the loop terminates after checking the incremented value of i.

- let variables are scoped to the immediate enclosing block denoted by { } (block scope).

let userMan: boolean = true;

var userAge: number = 81;For 310, you should use let (not var) to save yourself trouble.

Normal syntax

Fat arrow syntax

// Simple function

let hello = function(name: string): void {

console.log("Hello " + name);

}

// Single return value

let addTwo = function(n: number): number {

return n + 2;

}

// With no parameters

let helloWorld = function(): void {

console.log("Hello world");

}Typescript: Fat Arrow =>

// Simple function

let hello = (name: string): void => {

console.log("Hello " + name);

}

// Single return value

let addTwo = (n: number): number => {

return n + 2;

}

let addTwo = (n: number): number => n + 2;

// With no parameters

let helloWorld = (): void => {

console.log("Hello world");

}Try to get comfortable with this syntax - you'll see it often!

Java

TypeScript

// Types

boolean userMan = true;

int userAge = 81;

float userAverage = 10.5;

String userName = "Henri Bergson";

// Methods

public int multiply(int a, int b) {

return a * b;

}

// Classes

public class User {

public String firstName;

public User(String firstName) {

this.firstName = firstName;

}

public void sayHello() {

System.out.println("Hello!");

}

}

User myUser = new User("Henri");

myUser.firstName;

myUser.sayHello();// Types

let userMan: boolean = true;

let userAge: number = 81;

let userAverage: number = 10.5;

let userName: string = "Henri Bergson";

// Methods

function multiply(a: number, b: number): number {

return a * b;

}

// Classes

class User {

public firstName: string;

public constructor(firstName: string) {

this.firstName = firstName;

}

public sayHello(): void {

console.log("Hello!");

}

}

let myUser: User = new User("Henri");

myUser.firstName;

myUser.sayHello();The Basics, Again

Java

TypeScript

// Convert this code to TypeScript:

// Return the nth fibbonaci number.

// ASSUME: n is an integer >= 0

public int fib(int n) {

int a = 0;

int b = 1;

int c = 1;

if (n == 0)

return a;

for (int i = 2; i <= n; i++) {

c = a + b;

a = b;

b = c;

}

System.out.println(b);

return b;

}

// For you TODOThe Basics (Demo)

Java

TypeScript

// Convert this code to TypeScript:

// Return the nth fibbonaci number.

// ASSUME: n is an integer >= 0

public int fib(int n) {

int a = 0;

int b = 1;

int c = 1;

if (n == 0)

return a;

for (int i = 2; i <= n; i++) {

c = a + b;

a = b;

b = c;

}

System.out.println(b);

return b;

}

// Answer

// Return the nth fibbonaci number.

// ASSUME: n is an integer >= 0

function fib(n: number): number {

let a: number = 0;

let b: number = 1;

let c: number = 1;

if (n === 0)

return a;

for (let i: number = 2; i <= n; i++) {

c = a + b;

a = b;

b = c;

}

console.log(b);

return b;

}

The Basics (Demo)

Aside: Typescript vs. Javascript

- TS is a superset of JS: it has extra features.

- TS is typed while JS is not. This makes OOP a lot easier.

- TS is transpiled into JS, which means that it can run on anything that runs JS (with the right support).

If you already know JS, you should be able to jump into TS easily.

If not, TS also has lots of similarities to Java.

-

Java TO TypeScript

-

Node / Yarn

-

Async

What's Node?

Node.js is an open-source, cross-platform, JavaScript runtime environment that executes JavaScript code outside of a browser.

What you need to know:

- You use it to write and run JavaScript applications on your underlying OS, without a Web browser.

- You will run and test your program with node using npm or yarn.

- "node" and "node.js" are used interchangeably; the ".js" isn't a file extension, it's just the name of the product.

What's NPM and Yarn?

npm (Node Package Manager) and Yarn are both package managers that allow you to install JavaScript libraries that run in node.js

What you need to know:

- Whichever one you use, you will have to install Node - both of them run through the node command line.

- npm comes with Node.js; yarn does not.

- Some people prefer one over the other. Yarn tends to run a bit faster since it caches packages and installs all packages simultaneously.

- Choose one and stick with it. Don't try to bounce back and forth; you'll just get confused.

HOw will you use all of this in CPSC 310?

Short answer:

// npm: npm start npm test

// yarn: yarn start (or yarn run) yarn test

HOw will you use all of this in CPSC 310?

Longer answer:

"The packages and external libraries (aka all of the code you did not write yourself) you can use for the project are limited and have all been included for you in your package.json.

- You cannot install any additional packages.

- It is notable that a database is NOT permitted to be used; the data in this course is sufficiently simple for in-memory manipulation using the features built into the programming language.

- Essentially if you are typing npm install or yarn install you will likely encounter problems."

Short answer:

// yarn: yarn start (or yarn run) yarn test

// npm: npm start npm test

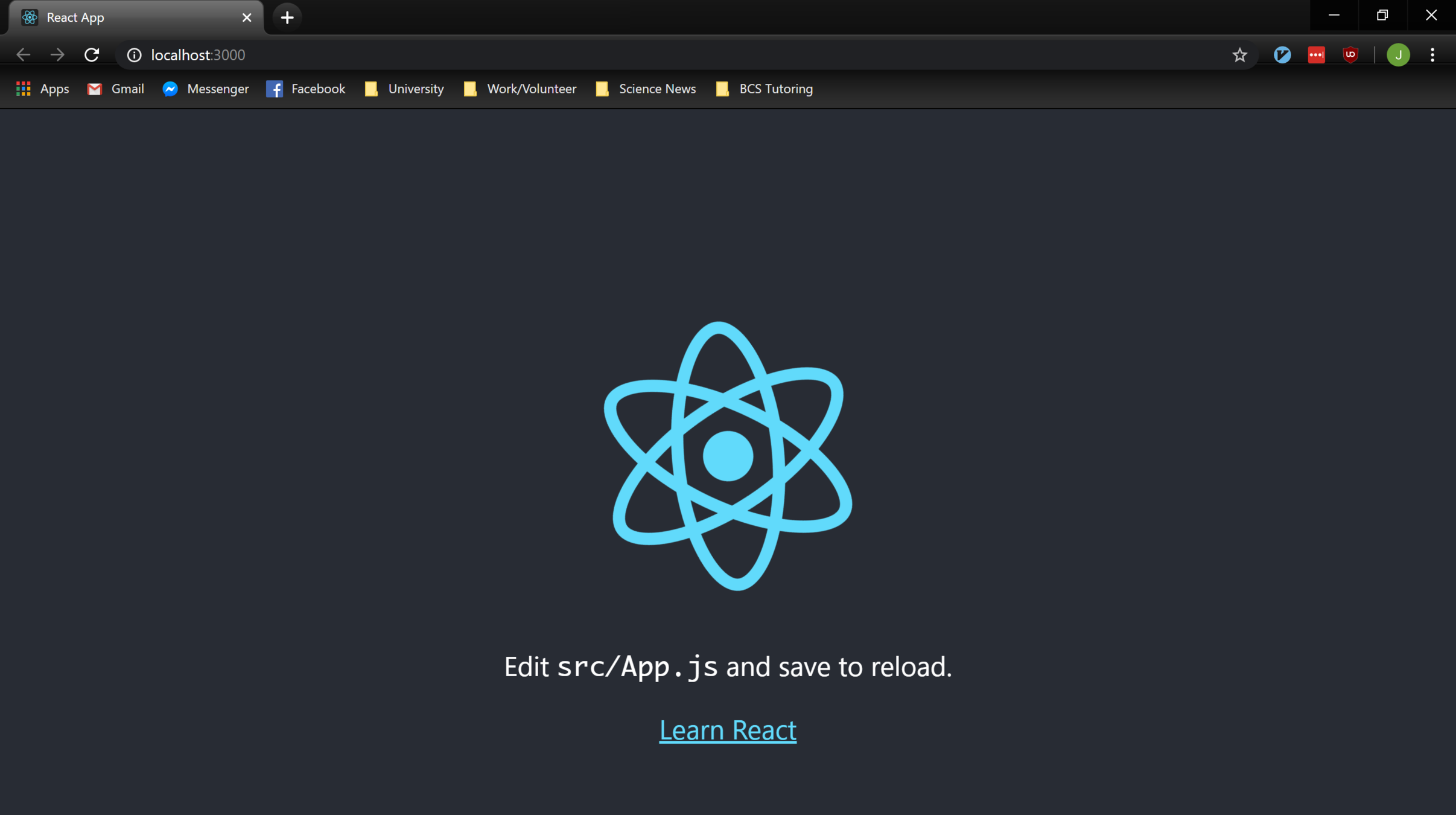

Demo time!

We're going to walk through the setup and launching of a simple application.

- Open up Node.js command prompt (Windows) or Terminal (Mac)

- Run the following commands:

npx create-react-app my-app

cd my-appThe first command simulates what the CPSC 310 staff will do behind the scenes*: make a project with all required scripts and packages. Note that npx is NOT a typo.

*You won't be creating a React application in 310.

The second command will navigate to the newly created project folder.

Demo time!

3. Start the application with one of the following commands:

yarn start || npm startIf this doesn't navigate to localhost:3000 in your browser, do that to make sure you get this landing page:

Demo time!

4. Quit the application by clicking Ctrl+C

5. (Optional) run the application's tests using one of these commands:

yarn test || npm testYou might have to hit `a` after entering this command.

You won't be using the same testing framework as the one in the demo, but you WILL be using the same command in npm/yarn to run your tests (found in src/App.test.js)

CPSC 310 uses the Mocha testing

framework: https://mochajs.org/

What's actually happening?

// package.json

{

"name": "my-app",

"version": "0.1.0",

"private": true,

"dependencies": {

"@testing-library/jest-dom": "^4.2.4",

"@testing-library/react": "^9.3.2",

"@testing-library/user-event": "^7.1.2",

"react": "^16.12.0",

"react-dom": "^16.12.0",

"react-scripts": "3.3.0"

},

"scripts": {

"start": "react-scripts start",

"build": "react-scripts build",

"test": "react-scripts test",

"eject": "react-scripts eject"

},

"eslintConfig": {

"extends": "react-app"

},

"browserslist": {

"production": [

">0.2%",

"not dead",

"not op_mini all"

],

"development": [

"last 1 chrome version",

"last 1 firefox version",

"last 1 safari version"

]

}

}When you type `npm start` or `yarn start`:

- Node looks inside package.json for a script with the key "start".

- Node then runs the corresponding script. In this case, it runs the "start" file found in the "react-scripts" node module*.

* Node modules can be found in your project's `node_modules` folder, and are automatically installed for your project. You shouldn't (have to) touch anything in this folder.

Congrats!

You ran a Node project!

Questions?

-

Java TO TypeScript

-

Node / Yarn

-

Async

What is asynchronous programming?

Almost all programs you've encountered so far are synchronous: they happen line by line.

console.log("AAAAA");

console.log("BBBBB");

console.log("CCCCC");

// outputs "AAAAA", "BBBBB", "CCCCC"But what if some processes and functions will take a lot of time to complete?

runTaskA(); // Takes 0.01 seconds

runTaskB(); // Takes 1 second

runTaskC(); // Takes 0.01 secondsWhat if we wanted to run task C while waiting for task B to finish?

Async programming lets us do things while waiting for other things to finish.

In JavaScript, this happens through the event loop. Watch this video for a really great explanation: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8aGhZQkoFbQ

callbacks

A callback is a function (passed to another function) that is expected to execute after the other function finishes.

let cb = function() {

console.log("I'm a callback!");

}

setTimeout(cb, 1000);- setTimeout() is an asynchronous function that takes in two parameters:

- A callback function

- Time in ms to wait before the callback is called

- Here, setTimeout waits 1 second before calling the function `cb`

- The function body can be written inside setTimeout() too.

Nested callbacks

Let's say we want to complete tasks A, B, and C one after the other. Maybe the results depend on each other.

There are lots of ways we could do this, but let's talk about the ways we don't want to do this first.

// Let's take a look at callbacks. They're messy.

setTimeout(function() {

console.log("Task A is done!");

setTimeout(function() {

console.log("Task B is done!");

setTimeout(function() {

console.log("Task C is done!");

}, 1000)

}, 1000)

}, 1000);

// What's one way we can fix this?

// We can name the functions and lift them to the top level:

let taskA = function() {

setTimeout(function() {

console.log("Task A is done!");

taskB();

}, 1000);

}

let taskB = function() {

setTimeout(function() {

console.log("Task B is done!");

taskC();

}, 1000);

}

let taskC = function() {

setTimeout(function() {

console.log("Task C is done!");

}, 1000);

}

taskA();

// But this could be bad for error handling: you have to

// handle every single error as it could happen in any

// of the tasks.Promises

"A Promise is an object that may produce a single value at some point in the future"

"Imagine that you’re a top singer, and fans ask day and night for your upcoming single.

You promise to send it to them when it’s published using their emails.

- When the song becomes available, all subscribed parties instantly receive it.

- Even if something goes very wrong, say, a fire in the studio, so that you can’t publish the song, they will still be notified.

Everyone is happy: you, because the people don’t crowd you anymore, and fans, because they won’t miss the single."

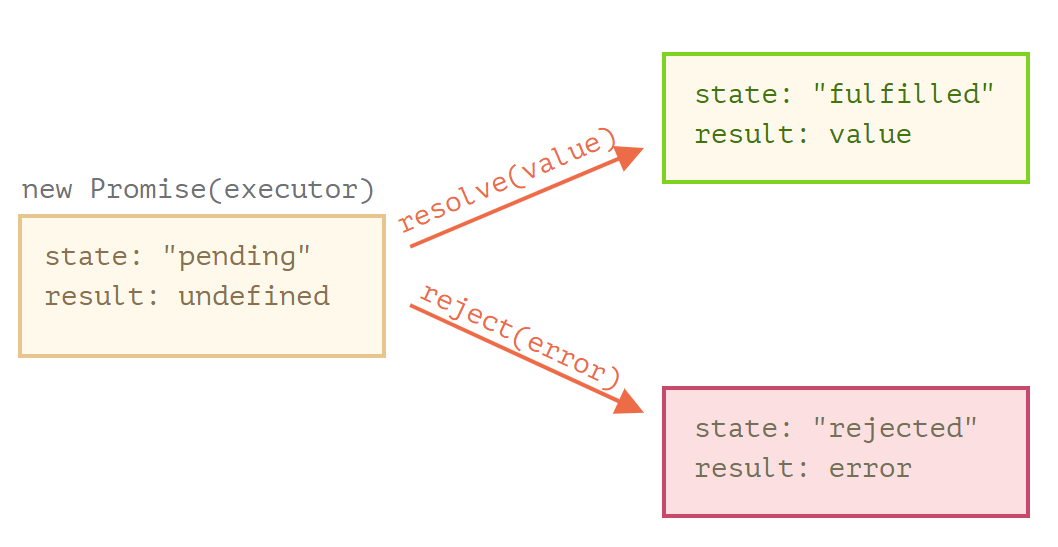

Promises (Syntax)

let promise = new Promise<string>(function(resolve, reject) {

// executor (the producing code, "singer")

});- The executor runs automatically whenever "new Promise()" is called

- The executor is usually a job that will take some amount of time

- The arguments resolve and reject are callbacks provided by JavaScript itself

- You can change the names, but this can make things confusing

- When the executor finishes its job, it should call one of the following:

- resolve(value): the job succeeded, with the given value

- reject(error): an error occurred, with the given object

Promises (Syntax)

let promise = new Promise<string>(function(resolve, reject) {

// executor (the producing code, "singer")

});A promise can be in one of three states:

- Pending

- Fulfilled - resolve() has been called

- Rejected - reject() has been called

A promise that is resolved or rejected is said to have settled.

Promises (Syntax examples)

let promiseA = new Promise<string>(function(resolve, reject) {

resolve("I'm done!");

});

let promiseB = new Promise<string>(function(resolve, reject) {

// after 1 second signal that the job is finished with an error

setTimeout(() => reject("I failed..."), 1000);

});

// A promise can only settle once.

let promiseC = new Promise(function(resolve, reject) {

resolve("done");

reject(new Error("…")); // ignored

setTimeout(() => resolve("…")); // ignored

});Promises (Try it yourself!)

// TODO: Create a Promise that generates a random integer

// between 0 and 9. The promise resolves with the string

// "This number is even" if the number if even, and rejects

// with the string "Error!" if the number is odd.

//

// Hint: to generate a random integer between 0 and 9, use:

// Math.floor(Math.random() * 10);Promises (Try it yourself!)

// TODO: Create a Promise that generates a random integer

// between 0 and 9. The promise resolves with the string

// "This number is even" if the number if even, and rejects

// with the string "Error!" if the number is odd.

//

// Hint: to generate a random integer between 0 and 9, use:

// Math.floor(Math.random() * 10);

let promise = new Promise<string>(function(resolve, reject) {

// n is a random integer between 0 and 9.

let n: number = Math.floor(Math.random() * 10);

if (n % 2 === 0) {

resolve("This number is even");

} else {

// Usually you'll want to reject with an Error object

// but let's keep this simple for now.

reject("Error!");

}

});Working with promises

Great, now we know how the promise object is constructed, and how it settles. But how do we work with a promise object if we don't know what it will be?

We can use .then(), .catch(), and .finally()

let promise = new Promise<string>(function(resolve, reject) {

//... do something, then resolve or reject.

});

promise

.then((whatPromiseResolvesWith) => {

console.log(whatPromiseResolvesWith);

})

.catch((whatPromiseRejectsWith) => {

console.log(whatPromiseRejectsWith);

})

.finally(() => {

console.log("I'm in the finally block");

});Working with promises

- .then() is called when the promise resolves

- It takes a function with one parameter: the object the promise resolved with*

- .catch() is called if the promise rejects

- It takes a function with one parameter: the object the promise rejected with

- .finally() is always called after the promise settles

- It takes a function with no arguments

promise

.then((whatPromiseResolvesWith) => {

console.log(whatPromiseResolvesWith);

})

.catch((whatPromiseRejectsWith) => {

console.log(whatPromiseRejectsWith);

})

.finally(() => {

console.log("I'm in the finally block");

});* .then() is actually a bit more complicated, but this is what you need to know.

Working with promises (Try it yourself!)

// TODO: Create a Promise that generates a random integer

// between 0 and 9. The promise resolves with the number

// if the number if even, and rejects with the number if it's odd.

//

// Handle the promise this way:

// 1. If the promise has resolved, print "Resolved with n"

// where n is the number.

// 2. If the promise has rejected, print "Rejected with n"

// where n is the number.

// 3. After this, print "Settled!"Working with promises (Try it yourself!)

// TODO: Create a Promise that generates a random integer

// between 0 and 9. The promise resolves with the number

// if the number if even, and rejects with the number if it's odd.

//

// Handle the promise this way:

// 1. If the promise has resolved, print "Resolved with n"

// where n is the number.

// 2. If the promise has rejected, print "Rejected with n"

// where n is the number.

// 3. After this, print "Settled!"

let promise = new Promise<number>(function(resolve, reject) {

// n is a random integer between 0 and 9.

let n: number = Math.floor(Math.random() * 10);

if (n % 2 === 0) {

resolve(n);

} else {

// Usually you'll want to reject with an Error object

// but let's keep this simple for now.

reject(n);

}

});

promise.then((n) => {

console.log("Resolved with " + n);

}).catch((n) => {

console.log("Rejected with " + n);

}).finally(() => {

console.log("Settled!");

});Promises can be chained!

new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

// Asynchronously check to see if a file exists

resolve(file);

}).then((res) => {

console.log("The file exists!");

// Asynchronously read in the contents of the file

return result2;

}).then((res) => {

console.log("Done reading in all the stuff!");

// Asynchronously make an API call

return result3;

}).then((res) => {

console.log("Made an API call!");

}).catch((err) => {

// Called if any error is encountered on the way

console.log("Error: " + err.message);

})Promises let us write asynchronous code as if it were synchronous!

More advanced promise syntax (on your own)

Promise.resolve() and Promise.reject() create resolved or rejected promises with the given values

Promise.resolve(value);

// Is basically equivalent to:

new Promise((resolve, reject) => resolve(value));

Promise.reject(error);

// Is basically equivalent to:

new Promise((resolve, reject) => reject(error));Promise.all() lets us execute multiple promises at the same time, and wait until they're all ready.

Promise.race() waits for the first settled promise and works with its result.

More details --> https://javascript.info/promise-api

Async/await syntax

Async/Await syntax makes it easier for us to work with promises.

It's not necessary, but it's nice to have.

A function with the "async" keyword always returns a promise.

async function fn(): Promise<string> {

return "value";

}

// is equivalent to:

/*

async function fn(): Promise<string> {

return Promise.resolve("value");

}

*/

fn().then((res) => console.log(res));Async/await syntax

The "await" keyword will only work inside async functions.

function synchronous(): string {

let value = await promise // will not work

}

async function fn(): Promise<string> {

let value = await promise // will work!

}

Why is this useful?

"await" makes JavaScript wait until the promise has settled before moving on to the rest of the method. This means that your program can do other things while waiting for the "await-ed" promise to settle.

Why not just use Promise.then()?

You can! It's just that async/await looks a bit cleaner, and makes debugging a lot easier.

Async/await syntax

Here's what something looks like with Promise.then()...

const makeRequest = () => {

return promise1()

.then(value1 => {

// do something

return Promise.all([value1, promise2(value1)])

})

.then(([value1, value2]) => {

// do something

return promise3(value1, value2)

})

}And the same code with async/await:

const makeRequest = async () => {

const value1 = await promise1()

const value2 = await promise2(value1)

return promise3(value1, value2)

}Async/await syntax

We can also use try/catch blocks inside async methods to deal with promises that have rejected:

async function f() {

try {

let response = await fetch('http://no-such-url');

} catch(err) {

// The promise returned by the call to fetch() is rejected

// with the err object.

alert(err); // TypeError: failed to fetch

}

}Async/await (Try it yourself!)

let promiseA = new Promise<any>(function(resolve, reject) {

let n: number = Math.floor(Math.random() * 10);

if (n % 2 === 0) {

setTimeout(() => resolve(n), 1000);

} else {

setTimeout(() => reject(new Error("Promise A failed...")), 1000);

}

});

// promiseA and generates a random number, waits 1 second, then resolves

// with that number if it's even, and rejects with an Error object if it's

// odd.

// Your task is to fill in the body of fn() using async/await syntax.

// You are to call promiseA and assign its value to a local variable

// called resA. If promiseA resolves, you should print "Success!" to the

// console and return resA multiplied by 2.

// If promiseA rejects, you should print the error message and return

// the value -1.

// A function signature has been provided for you.

async function fn(): Promise<number> {

// For you TODO

}

// This function call prints the result of fn() to the console.

// You can ignore it for our purposes.

fn().then((res) => console.log(res));Async/await (Try it yourself!)

let promiseA = new Promise<any>(function(resolve, reject) {

let n: number = Math.floor(Math.random() * 10);

if (n % 2 === 0) {

setTimeout(() => resolve(n), 1000);

} else {

setTimeout(() => reject(new Error("Promise A failed...")), 1000);

}

});

// Your task is to fill in the body of fn() using async/await syntax.

// You are to call promiseA and assign its value to a local variable

// called resA. If promiseA resolves, you should print "Success!" to the

// console and return resA multiplied by 2.

// If promiseA rejects, you should print the error message and return

// the value -1.

// A function signature has been provided for you.

async function fn(): Promise<number> {

try {

let resA: any = await promiseA;

console.log("Success!");

return resA * 2;

} catch(err) {

console.log(err.message);

return -1;

}

}

// This function call prints the result of fn() to the console.

// You can ignore it for our purposes.

fn().then((res) => console.log(res));Summary

-

TypeScript is a typed superset of JavaScript

- TS transpiles to JS

-

Node lets you run JavaScript/TypeScript on your computer

- npm and yarn are package managers that you'll use to run and test your project

-

Promises let us write asynchronous code like it's synchronous

- There are lots of ways to write code with Promises!

Good luck in 310!

References

- https://cyrilletuzi.github.io/javascript-guides/java-to-typescript.html

- https://reactjs.org/docs/create-a-new-react-app.html

- https://medium.com/javascript-scene/master-the-javascript-interview-what-is-a-promise-27fc71e77261

- https://javascript.info/async

- https://hackernoon.com/6-reasons-why-javascripts-async-await-blows-promises-away-tutorial-c7ec10518dd9

Terms

CPSC 310 instructors (and lots of industry folk) like to throw around terms and jargon without defining what it means. Here are some common terms you may hear:

- Front-end: the part of your program the user interacts with directly (like a webpage)

- Back-end: the part of your program that runs behind the scenes (like a web server)

- Boilerplate: sections of code that have to be included in many places with little or no alteration (ex. getters and setters for a class)

- Linter: a tool used to analyze code and flag bugs, syntax errors, etc. (think checkstyles in CPSC 210)

- Spec: short for "specification" - what the program should be

- API: "Application Programming Interface" - a service that programmers use to get data or features from a server, operating system, or something else