COMP1701-004

fall 2023

lec-07

Up 'n Coming

any A2 questions?

About Late Submissions

- I'll start pulling down assignments after I get home.

- If you don't email me about using one of your late days before then, I'll mark what's up on your GitHub repo at that time.

- If you do use one of your late days, I'll repeat the process at 5PM the next day.

speaking of A2, I'm a bit worried

-

13 folks who haven't pushed/sync'd (!)

-

9 folks who haven't grabbed it (!!!)

if it passes the "tears test", push - as last Thursday showed, sometime stuff goes down

this is not the habit you want to build

some A2 things I've seen make me want to say:

- If a magic number can be given a meaningful name, then you've got yourself a constant.

- Follow variable and constant naming conventions.

- I think many people should reacquaint themselves with the meaning of whole number.

- Use whitespace to make math expressions easier to read.

- Use whitespace to avoid "wall of text" source files.

We're done with onlinequestions - unless you want to convince me otherwise.

RECALL

speed

- What type and value does this have? f'{981:.1f}m'

- What does this do? print('my','my','my','my',sep=",")

- What will the following code print to the screen? Assume the user responds with 2 when prompted.

num_minutes = input('How many minutes did you work? ')

print(f"That's {num_minutes * 60} seconds!")Here comes some quickies. Don't answer them out loud - but if you aren't able to answer them all in a minute, you've got some review to do!

let's talk about these things today:

⦾ constants: a quick repeat

⦾ functions: the basics

⦾ functions: anatomy

⦾ functions: convention & best practices

⦾ functions: importing & using

⦾ functions: tracing

Yikes.

Lotta stuff.

No way we're getting through all of this today!

constants

constants

A constant is a variable whose little box in memory should NOT be changed.

// JS - try this in a browser console

const PI = 3.14;

PI = -1; // say WHAAAAT?!?!🙋🏻♂️❓🙋🏻♀️What does this look like in memory?

In most languages you'll encounter (like C++, JavaScript, and Java), the language will enforce this "no changes, dude" policy.

constants

# in Python SCREAMING_SNAKE_CASE means

# this variable should be considered

# a constant

PI = 3.14

diameter = 12

circumference = PI * diameter

# buuuuuuuuut...

PI = -1

# so much for followin' the rules

# madness!

circumference = PI * diameter In fact, you can't label a variable as constant in Python!

But Python...doesn't roll that way.

Instead, we rely on convention to visually indicate that a variable shouldn't be changed - but folks can totally ignore that convention and do the unthinkable.

A common practice I'd like you to follow: put your constants before any other code.

Spot the magic numbers - and give them names, if you feel they should be turned into a constant

YOUDO

area = (1/2) * base * heightplaylist_duration_in_seconds = 60 * playlist_duration_in_minutestotal_num_eggs = (12 * num_full_cartons) + num_loose_eggs

functions: the basics

functions: the basics

What's a function?

One way of coming at this question is to consider it from 2 different points of view:

- as a USER of a function, or

- as a CREATOR of a function

functions: the basics

Are you a function USER?

Then a function is a magic incantation you call that causes something to happen and/or gives you something.

An example of a function you've already used that causes something to happen:

An example of a function you've already used that gives you something:

print("Behold! I have harnessed the power of functions!")birth_month = input("What month were you born? ")🙋🏻♂️❓🙋🏻♀️What's kind of statement is this?

functions: the basics

Are you a function CREATOR?

Then a function is a sequence of instructions you give a name to that causes something to happen and/or gives something back.

A function that causes something to happen:

A function that gives something back:

def print_funcy_msg():

print("I put the FUNC back in FUNCTION.")def dollars_part(price):

return int(price)Functions are scarily awesome.

-

They make code easier to understand.

-

They allow code reuse, meaning faster development.

-

They make code testing much easier.

Fewer things to hold in brain at a time - large clumps of code becomes easier-to-understand names.

You can use a function over and over again - think of all the print and input you do, for example.

If you test your functions (you should), then when you use the tested functions in a larger application, you're using known-to-be-safe things.

Functions are, in fact, so awesome that I have written a poem about them.

"Functions make code easier to understand" cannot be understated

Imagine tossing this bad boy in your code every time you wanted to print something to the screen!

BTW

Case in point:

functions: anatomy

functions: anatomy

Let's dissect a function or two and learn some new vocabulary.

functions: anatomy

def greet():

print("Hello.")

print("My name is Inigo Montoya.")

print("You killed my father.")

print("Prepare to die.")}

function header

}

the "def", function name, brackets, and colon are all necessary!

function body

one or more Python statements, indented into a block

the header and body together make a function definition

Example 1: A function that just DOES SOMETHING for you

functions: anatomy

def squarea(side_length):

return side_length ** 2}

function header

}

the def, name, and colon are here as well - but now we have a parameter inside the brackets

function body

here's our block again - but now there's a return statement

again, the header and body together make a function definition

Example 2: A function that GIVES SOMETHING to you

functions: anatomy

A few more terms, 'cuz obviously your brain ain't nearly full enough by now.

def squarea(side_length):

return side_length ** 2def greet():

print("Hello.")

print("My name is Inigo Montoya.")

print("You killed my father.")

print("Prepare to die.")value-returning functions return something

void functions

don't

!!! PRINTING is NOT RETURNING !!!

!!! PRINTING is NOT RETURNING !!!

!!! PRINTING is NOT RETURNING !!!

!!! PRINTING is NOT RETURNING !!!

!!! PRINTING is NOT RETURNING !!!

functions: anatomy

One more.

Sorry.

def leftover_pizza(num_pies, num_slices_per_pie, num_friends):

total_slices = num_pies * num_slices_per_pie

return total_slices % num_friendslocal variables are variables found inside functions

They're "local" in the sense of a "local convenience store".

parameters are local variables that are given an initial value

We'll see example of this later when we trace functions.

functions:

naming convention & best practices

functions: convention & best practices

PEP 8 is pretty straightforward about function naming:

"Function names should be lowercase, with words separated by underscores as necessary to improve readability."

🙋🏻♂️❓🙋🏻♀️So they should be named the same as what?

follow these best practice recommendations when functions are involved

- Void functions DO something, so begin their names with VERBS.

-

display_msg(), scold_user(), move_robot()

-

- Value-returning functions GIVE BACK something, so their names should show WHAT.

-

date_of_birth(), seconds_in_month(), valid_response()

-

- Keep the number of parameters LOW.

- 0 and 1 are best; 2 or 3 is ok; 4+ feel guilty

- Keep your functions short.

- If you can keep things to 5 lines or less, you'll smile a lot more.

- One-liners are GOOD THINGS, not BAD THINGS.

- Use type hints with your function headers. (More on this on the next slide.)

type hints

(a.k.a type annotations)

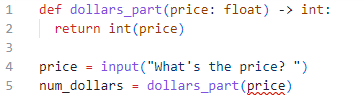

Some people - including me - think Python's casual attitude towards type checking leads to a lot of probems

def dollars_part(price):

return int(price)

price = input("What's the price? ")

num_dollars = dollars_part(price)🙋🏻♂️❓🙋🏻♀️What's the problem here?

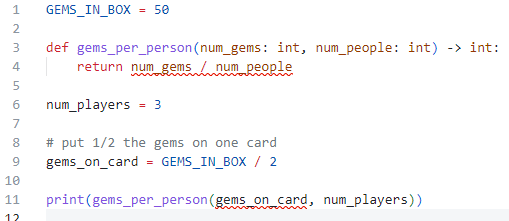

GEMS_IN_BOX = 50

def gems_per_person(num_gems, num_people):

return num_gems / num_people

num_players = 3

# put 1/2 the gems on one card

gems_on_card = GEMS_IN_BOX / 2

print(gems_per_person(gems_on_card, num_players))🙋🏻♂️❓🙋🏻♀️And here?

type hints make it clear to the writer AND reader of the function what TYPE of inputs and outputs are supposed to be used

def dollars_part(price: float) -> int:

return int(price)

price = input("What's the price? ")

num_dollars = dollars_part(price)GEMS_IN_BOX = 50

def gems_per_person(num_gems: int, num_people: int) -> int:

return num_gems / num_people

num_players = 3

# put 1/2 the gems on one card

gems_on_card = GEMS_IN_BOX / 2

print(gems_per_person(gems_on_card, num_players))Each paramter is given an expected type...

...and the expected return type is also provided.

def dollars_part(price: float) -> int:

return int(price)

price = input("What's the price? ")

num_dollars = dollars_part(price)GEMS_IN_BOX = 50

def gems_per_person(num_gems: int, num_people: int) -> int:

return num_gems / num_people

num_players = 3

# put 1/2 the gems on one card

gems_on_card = GEMS_IN_BOX / 2

print(gems_per_person(gems_on_card, num_players))Python doesn't care if you follow the type hints....

No change when you run these - they're still busted and you aren't being told that until they blow up!

...but most editors can be tweaked to make sure you're following the hints

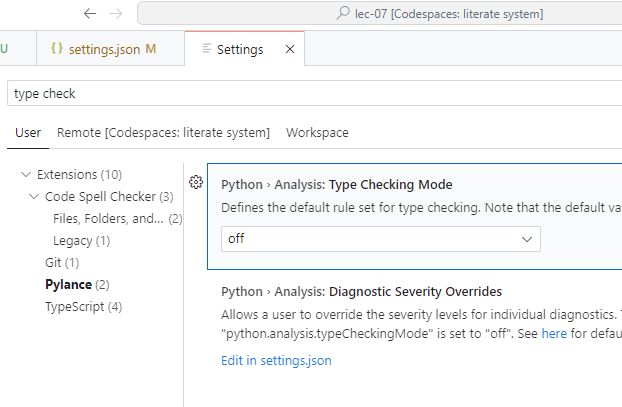

Go to File > Preferences > Settings from the hamburger menu

Enter type check in the search

Select Pylance

change Type Checking Mode from off to basic

Useful squigglies.

Voila!

functions: tracing

functions: tracing

Why even bother tracing?

It's a fundamental skill for reading code (your own and, more importantly, other people's).

It's a fundamental skill for debugging - finding problems in code (your own and other people's).

Less importantly, you'll often to be asked to figure out what some code does on quizzes and such - tracing improves your chances of getting these questions "right".

functions: tracing

Tracing gets a bit more complicated when functions are thrown into the mix.

As long as you're careful and pay attention, you'll be fine.

People tend to have different ways of tracking variables in a trace involving functions. I'll show you mine, but feel free to develop your own style.

functions: tracing

def display_welcome() -> None:

print("Why, hello there.")

print("Welcome to this humble trace.")

def main() -> None:

display_welcome()

main()new wrinkle: function calls

Typically, when tracing code on a test, you're asked to track any variables over time and say what the output is.

For this trace, there are no variables to trace, so we're just concerned with the output.

Trace this code: example 1

Apologies - needed to sneak yet another term in there!

Hint: you can always tell you're looking at a function call because of the bracket pairs ()!

functions: tracing

def display_welcome() -> None:

print("Why, hello there.")

print("Welcome to this humble trace.")

def main() -> None:

display_welcome()

main()Since there are no variables or parameters anywhere, our job becomes easier - we just need to make sure we run the code in the right order.

1

2

3

4

Start on the first line of code that's NOT a function definition.

3

4

OUTPUT

Why, hello there.

Welcome to this humble trace.

We can use numbers to track this flow of execution.

functions: tracing

MM_PER_CM = 10

def get_side_len_cm() -> float:

len_as_text = input("Length of side in cm? ")

return float(len_as_text)

def squarea(side_len: float) -> float:

return side_len ** 2

def display_result(side_len: float, area: float) -> None:

print(f"A {side_len}cm x {side_len}cm square has area {area:.1f}mm^2")

side_len_cm = get_side_len_cm()

side_len_mm = side_len_cm * MM_PER_CM

area = squarea(side_len_mm)

display_result(side_len_cm, area)function arguments

In this trace, there are variables and parameters, so we need to track them and the output.

Trace this code: ex 2

Another sneaker.

Assume the user enters 3.1 when prompted.

This is gonna hurt a bit.

You'll get used to this eventually - honest.

But it's still gonna hurt.

functions: tracing

MM_PER_CM = 10

def get_side_len_cm() -> float:

len_as_text = input("Length of side in cm? ")

return float(len_as_text)

def squarea(side_len: float) -> float:

return side_len ** 2

def display_result(side_len: float, area: float) -> None:

print(f"A {side_len}cm x {side_len}cm square has area {area:.1f}mm^2")

side_len_cm = get_side_len_cm()

side_len_mm = side_len_cm * MM_PER_CM

area = squarea(side_len_mm)

display_result(side_len_cm, area)Trace this code: ex 2

Assume the user enters 3.1 when prompted.

OUTPUT

Length of side in cm?

A 3.1cm x 3.1cm square has an area of 961.0mm^2

1

2,5

3

4

6

7,9

8

10

11

3

11

global

MM_PER_CM: 10

side_len_cm: 3.1

side_len_mm: 31.0

area: 961.0

get_side_len_cm

len_as_text: "3.1"

squarea

side_len: 31.0

display_result

side_len: 3.1

area: 961.0

1

5

6

9

3

!

!

!

RECAP RECAP

What did we talk about?