Politics through the Lens of Economics

Lecture 7: Electoral Rules and Voter Intimidation

Masayuki Kudamatsu

15 November, 2017

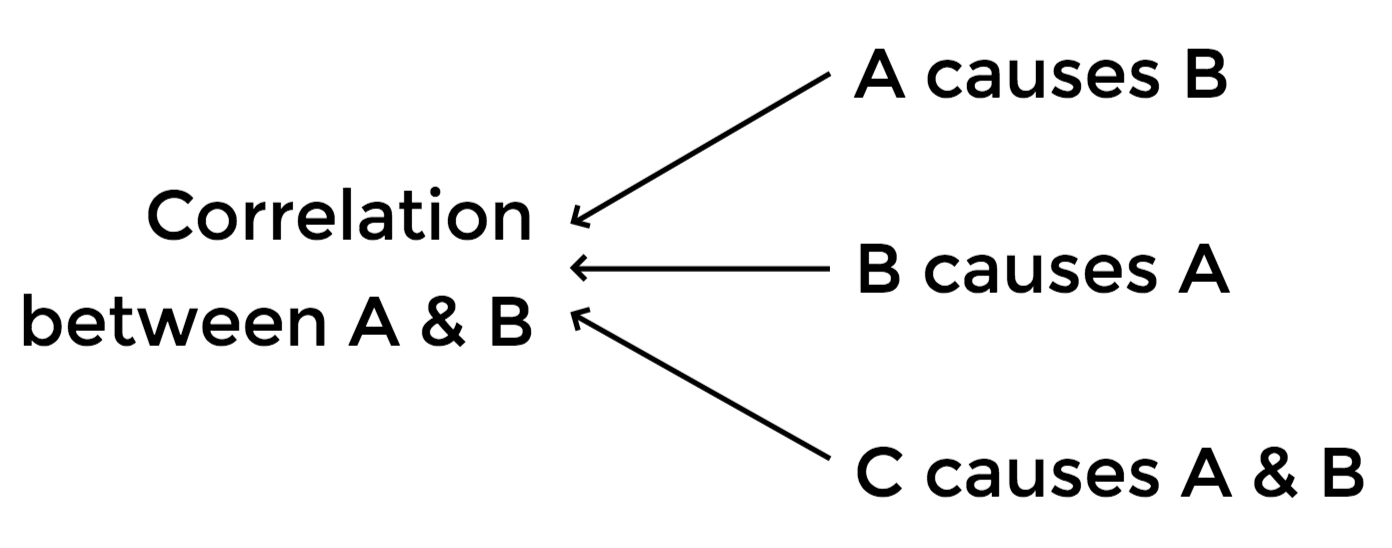

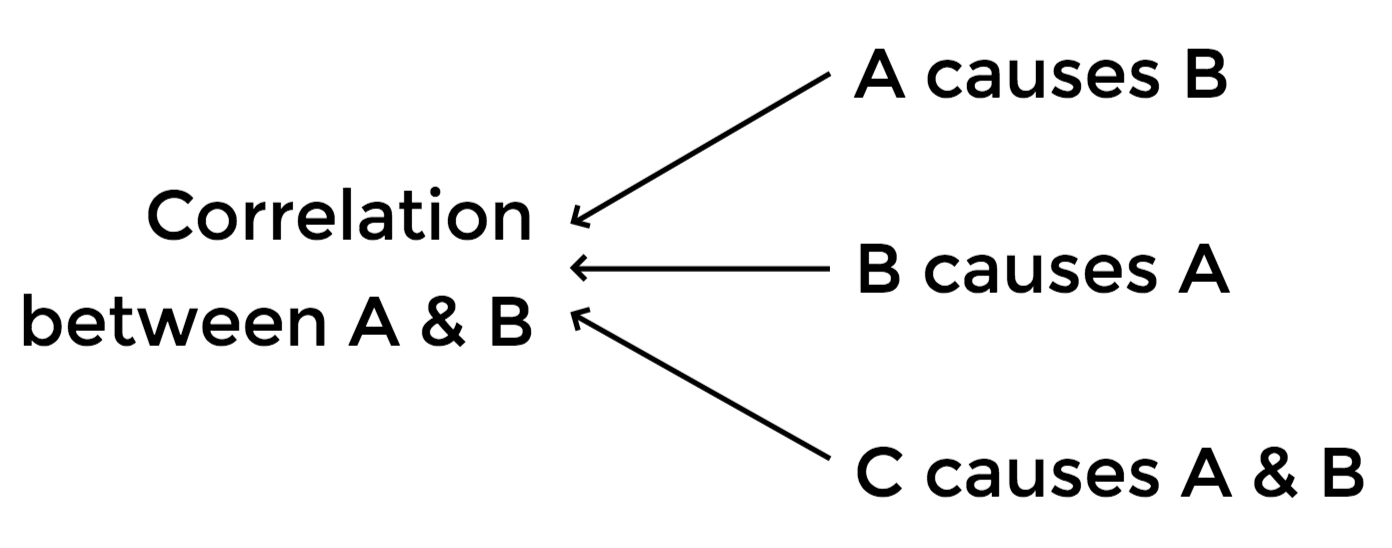

What evidence do we need to say

the probabilistic voting model explains

Why Japan hasn't legalized same-sex marriage?

Background information

Countries that have legalized same-sex marriage

Background information

Some municipalities in Japan issue

partnership certificates for same-sex couples

Image source: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Same-sex_marriage_in_Japan

Sapporo (2017)

Shibuya (2015)

Setagaya (2015)

Iga (2016)

Takarazuka (2016)

Naha (2016)

What evidence do we need to say

the probabilistic voting model explains

Why Japan hasn't legalized same-sex marriage?

What evidence do we need to say

the probabilistic voting model explains

Why Japan hasn't legalized same-sex marriage?

Come up with a wrong answer!

Today's Road Map

Impact of electoral rules

Voter intimidation

We apply the Probabilistic Voting Model to understand...

Today's Road Map

Impact of electoral rules

Voter intimidation

We apply the Probabilistic Voting Model to understand...

Motivation: Role of Political Institutions

So far in this course

Election outcomes were determined by a simple majority voting

In reality

How voting outcomes translate into who assumes office

depends on political institutions such as

Electoral rules (this lecture)

Presidential vs parliamentary systems (Lecture 13)

Term limits (Lecture 11)

Impact of electoral rules

Public goods

(welfare spending)

Geographically targeted spending

Public pension

Unemployment benefits

Local infrastructure

Fiscal transfer to local government

Composition of government expenditure

Outcome of interest:

Start with the standard probabilistic voting model

Two parties (A & B) offer policy

Voters choose which party to vote for based on policy and ideology

Step 1

Step 2

Step 3

The party who wins a majority

implement the offered policy

Modify the standard probabilistic voting model so that...

Two parties (A & B) offer how much to

Step 1

provide public goods

spend in each district

We assume there is a fixed amount of government revenue

i

ii

Voters choose which party to vote for based on policy and ideology

Step 2

Step 3

The party who wins a majority of seats

implement the offered policy

Modify the standard probabilistic voting model so that...

Step 2.5

Electoral rule determines how votes translate into seats in legislature

Road map

Each party's optimal mix of two policies

Impact of electoral rules on the optimal mix

Each party's optimal mix of two policies

Impact of electoral rules on the optimal mix

Road map

# of

citizens

Bias to

Party B

0

Distribution of citizens' ideological bias to party B

# of

citizens

Bias to

Party B

0

Without any policy, these citizens vote for:

A

B

# of

citizens

Bias to

Party B

0

If party A offers public good, citizens vote for:

A

Benefit

from public good

A

B

# of

citizens

Bias to

Party B

0

Doubling public good increases votes less than twice

A

Benefit from

2nd unit of public good

A

B

Extra votes

to win

Public good

provision

# of extra votes declines

as public good increases

Extra votes

to win

Targeted

spending

Same is true

for targeted spending

What's the optimal mix of these two policies to maximize # of votes?

Public goods

(welfare spending)

Geographically targeted spending

Public pension

Unemployment benefits

Local infrastructure

Fiscal transfer to local government

Extra votes

to win

Targeted

spending

Draw the graph

for targeted spending

from the right

Extra votes

to win

Public good

provision

Targeted

spending

Extra votes

to win

Targeted

spending

Draw the graph

for public good

from the left

Extra votes

to win

Public good

provision

Targeted

spending

Public good

Extra votes

to win

Targeted

spending

Amount of government revenue

Extra votes

to win

Public good

provision

Targeted

spending

Extra votes

to win

Consider

this mix of the two policies

Extra votes

to win

Public good

provision

Targeted

spending

Shaded area

= total # of votes

Extra votes

to win

Public good

provision

Targeted

spending

Can win more votes by less transfer

Extra votes

to win

Public good

provision

Targeted

spending

Can win more votes by more transfer

Extra votes

to win

Public good

provision

Targeted

spending

Maximize

total # of votes

Each party's optimal mix of two policies

Impact of electoral rules on the optimal mix

Road map

Modelling electoral rules

District magnitude

Electoral formula

# of legislators elected per district

How vote shares translate into seat shares in legislature

2 aspects of any electoral rules

Modelling electoral rules

Majoritarian election

District magnitude

Electoral formula

# of legislators elected per district

How vote shares translate into seat shares in legislature

1 per district

Largest vote share

= 100% seat share

Modelling electoral rules

Proportional Representation

District magnitude

Electoral formula

# of legislators elected per district

How vote shares translate into seat shares in legislature

All elected from one district

Vote share

= Seat share

# of

citizens

Bias to

Party B

0

1

Consider three districts

District 1: lots of Party A supporters

# of

citizens

Bias to

Party B

0

3

District 3: lots of Party B supporters

Consider three districts

# of

citizens

Bias to

Party B

0

2

District 2: "Swing" voters

Consider three districts

# of

citizens

Bias to

Party B

0

Alternatively, consider three sets of districts

And none has a majority of citizens

# of

citizens

Bias to

Party B

0

Majoritarian elections

Each district elects one legislator

by plurality rule

# of

citizens

Bias to

Party B

0

Proportional Representation

All legislators elected from the whole country

in proportion to vote share

Party's objective

Obtain the majority of seats to become the ruling party

In Proportional Representation

Obtain the majority of votes in the whole country

In Majoritarian Elections:

Obtain the majority of votes in two out of three districts

# of

citizens

Bias to

Party B

0

In majoritarian elections

Public good provision

doesn't affect election outcome

in District 1

Majority vote for A

# of

citizens

Bias to

Party B

0

In majoritarian elections

Public good provision

doesn't affect election outcome

in District 3

Majority

vote for B

# of

citizens

Bias to

Party B

0

In majoritarian elections

More votes from District 2

due to public good provision

count for winning the election

# of

citizens

Bias to

Party B

0

More votes from District 1

due to public good provision

DOES count for winnning

In proportional representation

# of

citizens

Bias to

Party B

0

More votes from District 3

due to public good provision

DOES count for winnning

In proportional representation

# of

citizens

Bias to

Party B

0

More votes from District 2

due to public good provision

DOES count for winnning

In proportional representation

Extra votes

to win

Public good

provision

PR

Majoritarian

Public good provision

is more effective under PR

to win a majority of seats

# of

citizens

Bias to

Party B

0

In majoritarian elections

Targeted spending to District 2

yields most extra votes

# of

citizens

Bias to

Party B

0

In proportional representation

Targeted spending to District 2

yields most extra votes

(Same as in majoritarian)

Extra votes

to win

Public good

provision

Transfer

to District 2

PR

Majoritarian

Extra votes from transfer is the same for both electoral rules

Extra votes

to win

Public good

provision

Transfer

to District 2

PR

Majoritarian

Optimal level of

public good provision

is larger under PR

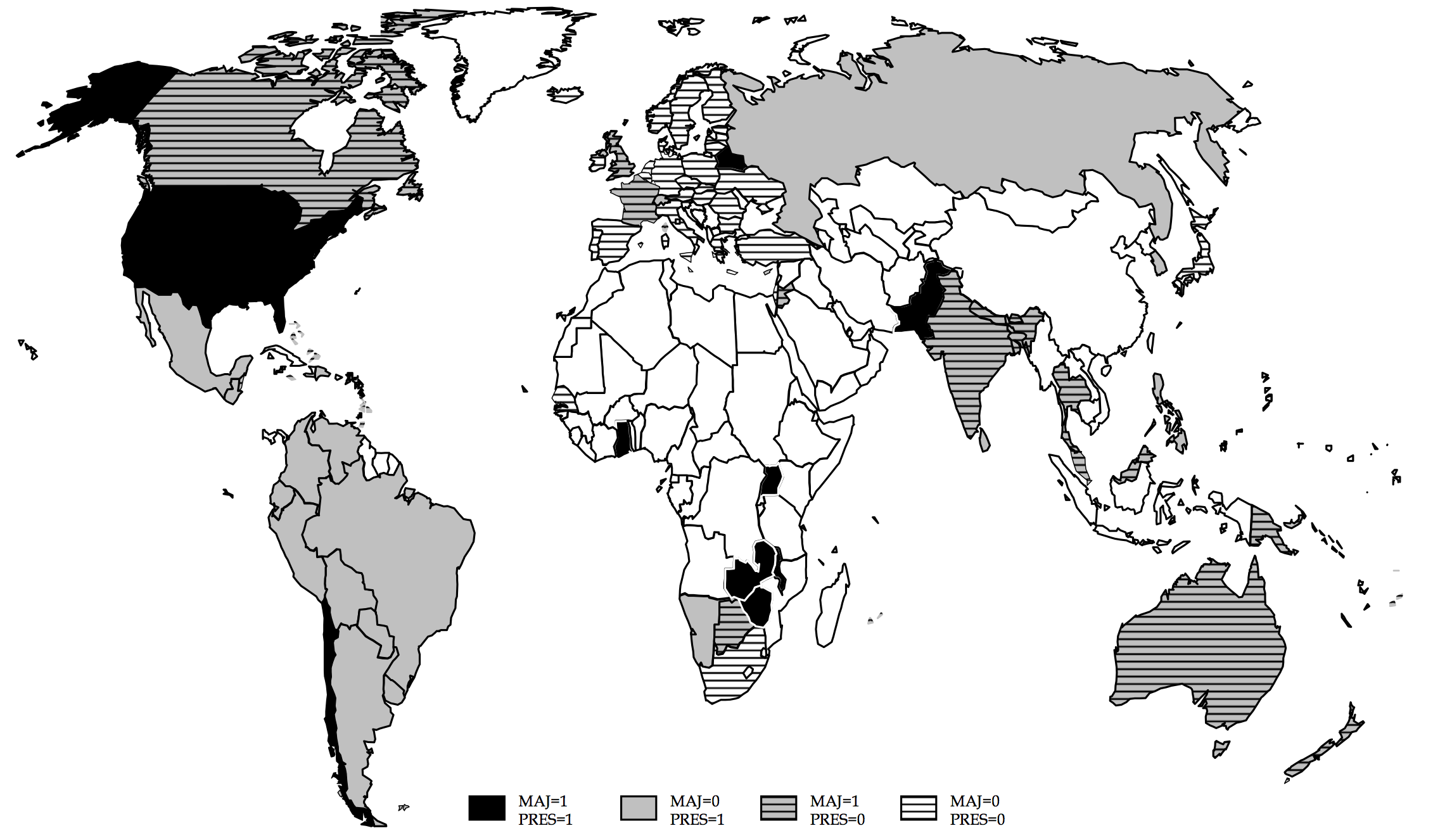

Evidence

Hard to prove causality running from electoral rules to policies

Electoral rules rarely change

Thus impossible to separate the impact of electoral rules

from that of country characteristics

Evidence

We can only check

if correlation is consistent with the theoretical prediction

Electoral rules around the world in 1998

Majoritarian

Proportional Representation

Not democratic

Average social welfare spending as % of GDP

Majoritarian Elections

Proportional Representation

4.7%

10.1%

This difference is not driven by

Forms of government (cf. Lecture 13)

Income per capita

Trade openness

Demographic composition

Years since democratization

Federal system

etc.

Source: Tables 1 and 4 of Persson and Tabellini (2004)

(data source: IMF's Government Financial Statistics)

Other impacts of majoritarian elections

(as opposed to PR)

Smaller size of government

Ambiguous impact on corruption

Smaller district magnitude increases corruption

Voting on individuals, not parties, reduces corruption

Today's Road Map

Impact of electoral rules

Voter intimidation

We apply the Probabilistic Voting Model to understand:

Motivation: Zimbabwe

1889: Colonized by UK

1965-1980: White minority rule

1980: Democratized, thanks to:

Robert Mugabe

and his ZANU-PF party

Motivation: Zimbabwe

Mugabe and ZANU-PF have allegedly harassed swing voters

2000: "... in Bikita West, a rural constituency that MDC had narrowly won...

Image source: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bikita_District

Martin Meredith (2002) Mugabe: Power and Plunder in Zimbabwe (p.215)

ZANU–PF militias set up camps around the constituency, beating up people, forcing them to attend rallies, and confiscated identity cards they needed in order to vote."

Motivation: Zimbabwe

Image source: www.bsap.org/hisgeography.html

Mugabe and ZANU-PF have allegedly harassed swing voters

1980: "Victoria Province, part of the Midlands and part of Manicaland, where both liberation parties had ground, were said to be the areas of most serious intimidation."

Liisa Laakso (1999) Voting Without Choosing: State Making and Elections in Zimbabwe (p.45)

Motivation: Zimbabwe

Why did Mugabe

target swing voters,

not loyal opposition voters?

Modify the Probabilistic Voting Model as follows

Party A is the ruling party who:

2. Maximize # of votes and minimize the government spending

So they can consume government revenue for their pleasure

1. Can disenfranchise a group of voters of their choice

i.e. Voter intimidation

# of

citizens

Bias to

Party B

0

Consider three districts

S

1. Swing districts

# of

citizens

Bias to

Party B

0

Consider three districts

A

2. Party A district

# of

citizens

Bias to

Party B

0

Consider three districts

B

3. Party B district

# of

citizens

Bias to

Party B

0

Under free and fair elections, with same amount of transfer:

# of voters swing

if targeting swing district

# of

citizens

Bias to

Party B

0

Under free and fair elections, with the same amount of transfer:

# of voters swing

if targeting party B's district

# of

citizens

Bias to

Party B

0

Under free and fair elections, with the same amount of transfer:

# of voters swing

if targeting party A's district

# of

citizens

Bias to

Party B

0

Under free and fair elections,

Both parties target

the swing district

Party A's optimization

Extra loss by spending one extra unit

Targeted

spending

Extra loss

Party A's optimization

Extra benefit from spending one extra unit

Targeted

spending

= the increase in winning probability weighted by rent

Party A's optimization

Extra benefit from spending one extra unit

Targeted

spending

= the increase in winning probability weighted by rent

Rent decreases with spending

Party A's optimization

Targeted

spending

Extra loss

Extra benefit

Net benefit is maximized where these two lines intersect

# of

citizens

Bias to

Party B

0

Both parties target

the other two districts

What if Party A disenfranchise voters in the swing district?

# of

citizens

Bias to

Party B

0

But transfer

swings less voters

What if Party A disenfranchise voters in the swing district?

Targeted

spending

Extra benefit

What if Party A disenfranchise voters in the swing district?

Extra benefit from additional transfer: shrinks

Swing district targeted

Loyal districts

targeted

# of

citizens

Bias to

Party B

0

On the other hand, total # of voters drops

What if Party A disenfranchise voters in the swing district?

Swinging one voter increases

vote share more

Targeted

spending

Extra benefit

What if Party A disenfranchise voters in the swing district?

Extra benefit from additional transfer: expands

All citizens vote

Swing district

disenfranchised

# of

citizens

Bias to

Party B

0

What if Party A disenfranchise voters in the swing district?

If swing districts are

very responsive

to transfer...

Targeted

spending

Extra benefit

What if Party A disenfranchise voters in the swing district?

Extra benefit from additional transfer: shrinks in net terms

Free and fair election

Swing district

disenfranchised

If swing districts are

very responsive

to transfer...

Targeted

spending

What if Party A disenfranchise voters in the swing district?

If swing districts are

very responsive

to transfer...

Spending

drops

Party A can consume more of the government budget

# of

citizens

Bias to

Party B

0

What if Party A disenfranchise voters in Party B's district?

# of

citizens

Bias to

Party B

0

What if Party A disenfranchise voters in Party B's district?

Party A's vote share

is larger

Party A is more likely to win than if intimidating swing voters

# of

citizens

Bias to

Party B

0

What if Party A disenfranchise voters in Party B's district?

Both parties target

the swing district

Party A cannot consume more of the government budget

Disenfranchising the swing district is preferred if

The swing district is very responsive

Increase in

probability of winning

by disenfranchising party B's supporters

>

Increase in

the govt budget that can be consumed

by disenfranchising swing voters

This is the case when

Today's summary

Proportional representation elections induce politicians

to provide more public goods than majoritarian elections

In countries where politicians can consume govt budget

they may want to disenfranchise swing voters

Probabilistic voting model is a useful framework

to consider the division-of-a-pie policy issues

Next lecture...

Legislative Bargaining Model

Image source: i.huffpost.com/gen/1883261/images/n-NATIONAL-DIET-large570.jpg

Model of politics #4

This lecture is based on the following academic articles and books:

Chapter 8 of Persson, Torsten, and Guido Tabellini. 2000. Political Economics: Explaining Economic Policy. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Persson, Torsten, and Guido Tabellini. 2004. “Constitutional Rules and Fiscal Policy Outcomes.” American Economic Review 94(1): 25–45.

See also Persson, Torsten., and Guido Enrico Tabellini. 2003. The Economic Effects of Constitutions. MIT Press.

Robinson, James A, and Ragnar Torvik. 2009. “The Real Swing Voter’s Curse.” American Economic Review 99(2): 310–15.