Politics through the Lens of Economics

Lecture 12: Voter Turnout

20 December, 2017

Masayuki Kudamatsu

Term Paper Timeline

| Wed 17 January | My last lecture |

| Wed 24 January | Workshop |

| Thu 15 February (9 am) | Submission deadline |

Read pages 24-108 of this book during the winter holidays

Recap of

when we can say a theory explains reality

Theory

II

Assumptions

Predictions

+

Hold in reality?

Consistent with reality?

The political agency model

Theory

II

Assumptions

Predictions

+

Citizens want a particular policy

Incumbent will be kicked out

if he/she fails to deliver the policy

Can the political agency model explain

why the sales of cigarettes isn't banned in Japan

Discussion Time

Aim to fail !

Motivation for Today

Citizens always vote, never abstain

In the previous lectures we assumed:

In reality:

Not every voter turns out at national elections

Question for Today

Why do some people vote while others abstain?

Four models of voter turnout

Information aggregation model

Mobilization model

Pivotal voter model

Ethical voter model

Today's Road Map

Four models of voter turnout

Information aggregation model

Mobilization model

Pivotal voter model

Ethical voter model

Today's Road Map

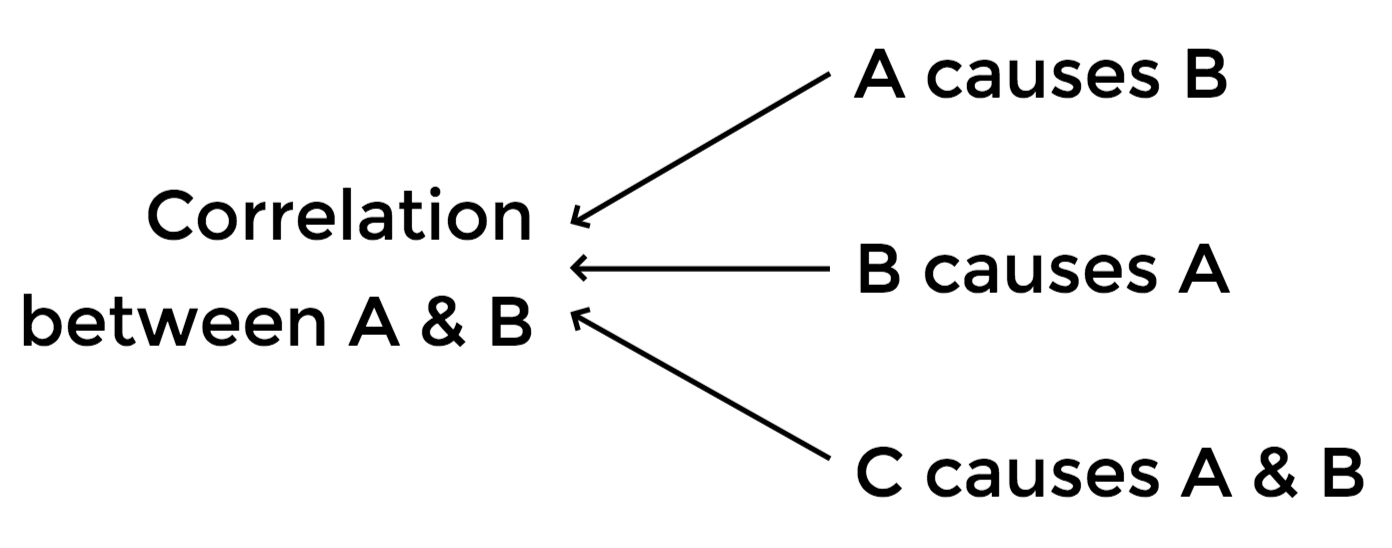

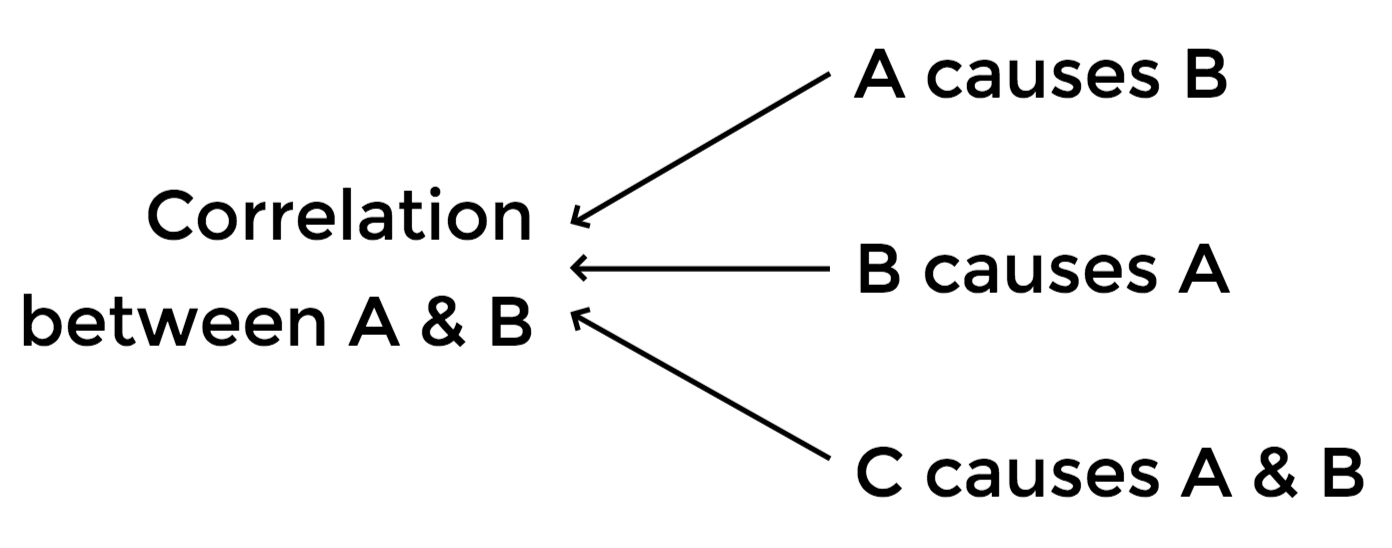

Economists think... (cf. Lecture 1)

We take an action if

Benefit

>

Cost

Applying this logic to going to poll

Benefit

>

Cost

Citizens go to poll if

Citizens abstain if

Benefit

Cost

<

Applying this logic to going to poll

Benefit

>

Cost

Citizens go to poll if

Citizens abstain if

Benefit

Cost

<

What's the benefit of going to poll?

Benefit of going to poll

Victory of my favorite candidate

weighted by

Probability

of my vote being pivotal

If I vote A, A wins.

But if I vote B, B wins.

Benefit of going to poll

Victory of my favorite candidate

weighted by

Probability

of my vote being pivotal

If I vote A, A wins.

But if I vote B, B wins.

How large is this probability?

Probability of my vote being pivotal

In a large election (e.g. national elections)

An individual vote will almost never change the election outcome

100,000,000+ voters across Japan

Your single vote matters only when

those who vote are equally split between two top candidates

Probability of my vote being pivotal

If we assume whether each citizen votes is random

we can calculate the probability of being pivotal

See Myerson (2000) for detail.

With 5 million citizens, it's only

0.00000081079%

Optimal behavior of citizens

>

Citizens go to poll if

Cost

Victory of my favorite candidate

x

Probability of my vote being pivotal

0.00000081079%

1 yen

124 million yen

This seems very unlikely

Implication

Only a small cost of voting

Bad weather

Schedule conflict

will then dissuade everyone from voting in national elections

Take to data...

In reality, many people, if not all, do vote in a large election

In poorer countries, people even form a long queue to vote

Image source: The Telegraph (2014)

South Africa in 2014

Take to data...

Very small

benefit from

going to poll

Non-zero

turnout

in reality

vs

Zero

To solve this puzzle, we need to assume the cost of voting is

or

Negative

(i.e. voting per se makes people happier)

Four models of voter turnout

Information aggregation model

Mobilization model

Pivotal voter model

Ethical voter model

Today's Road Map

Cost of voting

Zero

Negative

Negative

Each approach has a challenge

If the cost of voting is zero

Why do some people abstain from voting?

If the cost of voting is negative

Why do some people value voting per se?

Four models of voter turnout

Information aggregation model

Mobilization model

Pivotal voter model

Ethical voter model

Today's Road Map

The full-fledged model is highly mathematical

Here we see a simple version of the model

Information aggregation model

Voter 1: always prefer candidate 1

Consider an election with two candidates, 1 and 2

(Could also be a referendum on the proposed policy)

Suppose there are four voters

Voter 2, 3, 4: prefers the "correct" candidate

Voters 2, 3: do not know which candidate is "correct"

Voter 4: knows which candidate is "correct"

The majority rule decides which candidate wins

Flip a coin if it's a tie

Information aggregation model (cont.)

Citizen 1's optimal voting

Go to poll and vote candidate 1

Cost of voting is zero

A very small probability of being pivotal

is enough for citizen 1 to go to poll

Citizen 4's optimal voting

Go to poll and vote the correct candidate

Cost of voting is zero

A very small probability of being pivotal

is enough for citizen 4 to go to poll

Summary so far

Voter 1 goes to poll and vote candidate 1 (by assumption)

Voter 4 goes to poll and vote candidate 1 if 1 is correct

candidate 2 if 2 is correct

Summary so far

Voter 1 goes to poll and vote candidate 1 (by assumption)

Voter 4 goes to poll and vote candidate 1 if 1 is correct

candidate 2 if 2 is correct

If 1 is correct

2 vs 0

If 2 is correct

1 vs 1

Proposed equilibrium

Voter 2 votes 2

Voter 3 abstains

We check if these actions are optimal

given the other voter's behavior

Voter 2's optimal voting

Given that voter 3 abstains...

If 1 is correct

2 vs 0

If 2 is correct

1 vs 1

Voter 2's optimal voting

If 1 is correct, 1 will win anyway

If 1 is correct

2 vs 0

Voter 2's optimal voting

If 2 is correct, 2 will win for sure by voting 2

If 2 is correct

1 vs 1

Voter 2's optimal voting

If 1 is correct, 1 will win anyway

Voting 2 is optimal

If 1 is correct

2 vs 0

If 2 is correct

1 vs 1

If 2 is correct, 2 will win for sure by voting 2

Voter 2's optimal voting

Voting 2 is optimal

If 1 is correct

2 vs 1

If 2 is correct

1 vs 2

If 1 is correct, 1 will win anyway

If 2 is correct, 2 will win for sure by voting 2

Voter 3's optimal voting

Given that voter 2 votes 2...

If 1 is correct

2 vs 1

If 2 is correct

1 vs 2

Voter 3's optimal voting

If voting 1...

Voter 3's optimal voting

If 1 is correct

2 vs 1

If voting 1...

The outcome won't change if 1 is correct

Voter 3's optimal voting

If 2 is correct

1 vs 2

If voting 1...

A wrong candidate can win if 2 is correct

Voter 3's optimal voting

If 2 is correct

1 vs 2

If voting 1...

A wrong candidate can win if 2 is correct

The outcome won't change if 1 is correct

No reason to vote 1

If 1 is correct

2 vs 1

Voter 3's optimal voting

If voting 2...

Voter 3's optimal voting

If 2 is correct

1 vs 2

If voting 2...

The outcome won't change if 2 is correct

Voter 3's optimal voting

If 1 is correct

2 vs 1

If voting 2...

A wrong candidate can win if 1 is correct

Voter 3's optimal voting

If 1 is correct

2 vs 1

If 2 is correct

1 vs 2

If voting 2...

The outcome won't change if 2 is correct

A wrong candidate can win if 1 is correct

No reason to vote 2

Voter 3's optimal voting

If abstaining...

Voter 3's optimal voting

If 1 is correct

2 vs 1

If 2 is correct

1 vs 2

If abstaining...

The correct candidate wins in both cases

Abstention is optimal

Summary of uninformed voters' behavior

Voter 3 abstains to let the informed voter 4 be decisive

Given that voter 2 votes 2

Voter 2 votes 2 to let the informed voter 4 be be decisive

Voter 1 always votes 1 even if 1 is wrong

By voting 2, it's a tie so the informed voter 4 can decide

Given that voter 3 abstains

Implication

Some people advocate we must go to the polls

Don't listen to them

if you really don't know whom to vote

and no candidate is ideologically popular

Do uninformed citizens really abstain?

Many studies show the correlation

But those who want to vote may try harder to obtain information

A referendum in Copenhagen has a better answer

Do uninformed citizens really abstain?

Decentralization experiment in Copenhagen

Jan 1997

Primary schools, daycare, elderly care, etc.

Experiment was evaluated by a consulting firm

4 out of 15 districts start the experiment

of decentralizing the city administration

Late 1999

Sep 2000

Referendum on whether to extend decentralization

to all districts or abolish it

The majority vote for abolishing

Jan 2002

Experiment was terminated

Testing whether information raises turnout

Citizens in the 4 experiment districts

More informed about the benefit of decentralization

Turnout should be higher than in the other 11 districts

Not by their own choice but by external forces (i.e. city govt)

Data collection

Telephone survey of citizens in Copenhagen

conducted 2 months after the referendum

Ask their opinions on the decentralization experiment

Measuring informed-ness

Went well

Medium well

Bad

Don't know

Informed

Uniformed

Evidence from a referendum in Copenhagen

| Districts | % of informed citizens | Turnout (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Experiment | ||

| Other |

Source: Table 2 of Lassen (2005)

Evidence from a referendum in Copenhagen

| Districts | % of informed citizens | Turnout (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Experiment | 61.9 | |

| Other | 49.1 |

Source: Table 2 of Lassen (2005)

Evidence from a referendum in Copenhagen

| Districts | % of informed citizens | Turnout (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Experiment | 61.9 | 78.4 |

| Other | 49.1 | 69.0 |

Source: Table 2 of Lassen (2005)

More voters abstain in response to a larger cost of voting such as

Bad weather

Registration requirement (not in Japan, though)

Time to think about whom to vote

Distance to the polling station

So the cost of voting is NOT zero...

Data shows

Limitation of the information aggregation model

The cost of voting is assumed to be zero

We need to assume voting per se is valuable

Where does the benefit of voting come from?

Voters belong to groups of like-minded people

with the same preference over candidates

Cast a ballot if there is a consumption benefit from doing so

Two approaches

Mobilization model

Ethical voter model

Some economists propose group-based voting models in which

Four models of voter turnout

Information aggregation model

Mobilization model

Pivotal voter model

Ethical voter model

Today's Road Map

The leader of like-minded people's group

determines the level of turnout among his/her group

To do so, the leader allocates costly resources to voters

Mobilization model

e.g.

Trade Union (such as 連合 with 6m+ members)

Environmental groups

Religious groups (such as 創価学会 with 8m+ households)

Then it boils down to a model of costly voting with a few voters

Mobilization model (cont.)

With a few voters, the probability of being pivotal is not too small

Each group's leader

chooses # of votes for his/her favorite candidate

Limitation of the mobilization model

Unclear how leaders affect each voter's decision to vote

Social pressure?

Then why does each voter punish those abstaining?

How does each voter monitor the behavior of each other's?

Four models of voter turnout

Information aggregation model

Mobilization model

Pivotal voter model

Ethical voter model

Today's Road Map

Ethical Voter Model

Basic idea: "rule-utilitarian"

e.g.

Why don't some people throw away rubbish on street?

They choose the behavior that

if everyone follows the same behavior

society is in the best shape

Ethical Voter Model

This seems applicable to voting

Voters are motivated by a sense of civic duty

They cast a vote based on how well society is

(e.g. unemployment rate)

not just on how well they themselves are doing

Basic idea: "rule-utilitarian"

Again the full-fledged model is quite mathematical

We discuss a simple version of the model to show the main idea

Ethical Voter Model (cont.)

Consider two voters in a referendum

Both voters prefer

a proposal to be approved

The proposal is approved

if at least one voter votes yes

Ethical Voter Model (cont.)

Cost of voting on the day of the referendum: uncertain

Weather, How busy they are, Illness, etc.

Voters collectively decide

a cutoff voting cost below which they go to poll

By following this rule

they derive psychological benefits larger than the cost of voting

2's cost

1's cost

2's cost

1's cost

Cutoff

Cutoff

2's cost

1's cost

Cutoff

Cutoff

At least one voter casts a yes vote

so the proposal passes

2's cost

1's cost

Cutoff

Cutoff

Neither votes

so the proposal is rejected

2's cost

1's cost

Cutoff

Cutoff

A higher cut-off makes the adoption more likely

But the expected cost of voting increases

Extra

cost

Cutoff

The higher the cutoff, the larger the extra cost

Increase the cutoff from 10 to 11: extra cost is 11

11 to 12

12

Extra

benefit

Cutoff

The higher the cutoff, the smaller the extra benefit

2's cost

1's cost

Cutoff

Cutoff

The higher the cutoff, the smaller the extra benefit

Extra

benefit

or cost

Cutoff

Optimal cutoff maximizes the net benefit

Optimal

cutoff

Extra benefit

Extra cost

Extra

benefit

or cost

Cutoff

If the benefit from passing the proposal is larger

Optimal

cutoff

Extra benefit

Extra cost

Extra

benefit

or cost

Cutoff

If the benefit from passing the proposal is larger

Optimal

cutoff

Extra benefit

That is, turnout is higher

Extra cost

Turnout is higher for more important elections

Turnout for national elections in Japan

Lower House

Upper House

Supporting evidence:

Limitation of ethical voter model

How can voters collectively decide the cost cutoff?

Today's lessons

1

2

3

The standard logic of economics

cannot explain why some people go to poll and others don't

(If the cost of voting is zero)

Uninformed citizens may prefer abstaining

Some citizens must benefit from voting per se

but we don't exactly know why

Next Lecture...

Lobbying

Image source: www.thenation.com/article/shadow-lobbying-complex/

Merry Xmas & Happy New Year !

This lecture is based on the following academic articles:

Feddersen, Timothy J. 2004. “Rational Choice Theory and the Paradox of Not Voting.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 18(1): 99–112.

Lassen, David Dreyer. 2005. “The Effect of Information on Voter Turnout: Evidence from a Natural Experiment.” American Journal of Political Science 49(1): 103–18.