Politics through the Lens of Economics

Lecture 13: Lobbying

Masayuki Kudamatsu

10 January, 2018

NRA (National Rifle Association) in U.S.

Motivation: Politically influential interest groups

Most influential in U.S. (Fortune Power 25 in 2005)

National Rifle Association (NRA)

AARP (formerly American Association of Retired Persons)

National Federation of Independent Business

American Israel Public Affairs Committee

Motivation: Politically influential interest groups

Motivation: Politically influential interest groups

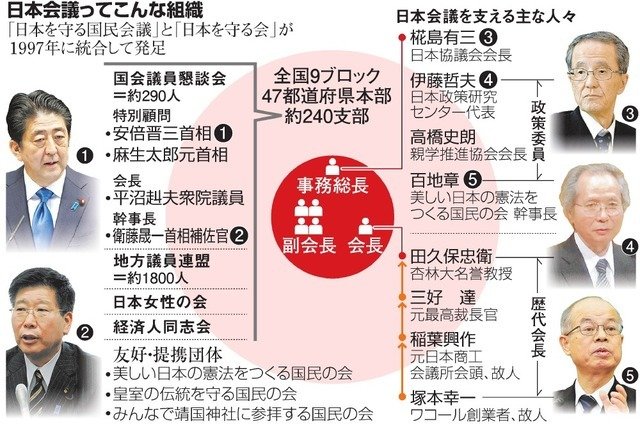

日本会議

Motivation: Politically influential interest groups

In what way

do these interest groups

influence policy-making?

Today's Road Map

Campaign contributions versus lobbyists

Return to hiring lobbyists

Connection or expertise?

Methods of influencing policy-making

Campaign contributions

Interest

Groups

Politicians

Lobbyists

Hire

?

Theories on campaign contributions

Two types of theories on how contributions affect policy-making

Buy votes in legislature

Help politicians win elections

Interest groups promise to

pay money

if a legislator votes

in their preferred way

Interest groups pay money to

their favourite candidate

so he/she can spend more

on electoral campaign

These theories were popular among economists in the 1990s.

But...

Too little money,

compared to the value of policies at stake

$590,000b

Federal govt

consumption & investment

in 2000

Campaign contributions

in national elections

in 2000

$3b

Source: Ansolabehere et al. (2003), p. 110

Too little money,

compared to the value of policies at stake

$134,000,000,000

Defense

procurement contracts

in 2000

Campaign contributions

by defense industry

in 2000

$13,200,000

Source: Ansolabehere et al. (2003), p. 110

Too little money,

compared to the value of policies at stake

$1,000,000,000

Price supports

for diary products

in 2002

Campaign contributions

by diary producers

in 2000

$1,300,000

Source: Ansolabehere et al. (2003), pp. 110-111

Contributions don't change how legislators vote

Chamber of Commerce, an interest group, calculates

% of times each member of Congress votes with the group

for bills relevant for the group, from 1978 to 1994

For a given legislator, this percentage does not change much

in response to more/less campaign contributions from corporations

Source: Table 2 of Ansolabehere et al. (2003)

So what are campaign contributions for?

Consumption, like a lottery ticket

Access fee to politicians

They'll listen to you, by paying money

But they won't necessarily support your policy

We do not know more than this

Lobbying industry

In the past decade or so

economists (and political scientists) focus more on lobbying industry

partly because the data has become available

Data on the U.S. lobbying industry

Lobbying Disclosure Act of 1995

requires all lobbyists to report (twice a year):

Their names and previous positions in govt

Clients' names and industries

Revenue received from each client

List of bills they lobby for/against

Data can be downloaded at Senate Office of Public Records (SOPR)

Center for Responsive Politics summarises the data

Data on the U.S. lobbying industry (cont.)

Collection of biographies of lobbyists

compiled by Columbia Books and Information Services

Of which about 17,000 can be matched in www.lobbyists.info

About 37,000 lobbyists for 1999-2008 in the SOPR data

Source: Bertrand et al. (2014), p. 3889

Money involved in U.S. in 2012

Campaign contributions

Interest

Groups

Politicians

Lobbyists

Hire

?

$750,000,000

$3,500,000,000

Source: de Figueiredo and Richter (2014), p. 165

What do lobbyists do?

Advise Congress committee members on bill proposals

Give access to politicians they know

Help politicians draft bills

Today's Road Map

Campaign contributions versus lobbyists

Return to hiring lobbyists

Connection or expertise?

Measurement

We need the following three pieces of data

Enactment of a policy

Lobbying expenditure by each lobbying firm

Policies each lobbying firm lobbies for/against

Measuring the enactment of a policy

Collect all the bills on the energy sector

introduced during the 110th Congress

(2007-2008: last 2 years of George W Bush's 2nd-term presidency)

Including those the committees didn't submit to the floor

Divide a bill into sections

One bill may deal with several policies

A bill section deals with one specific policy

Measuring the enactment of a policy (cont.)

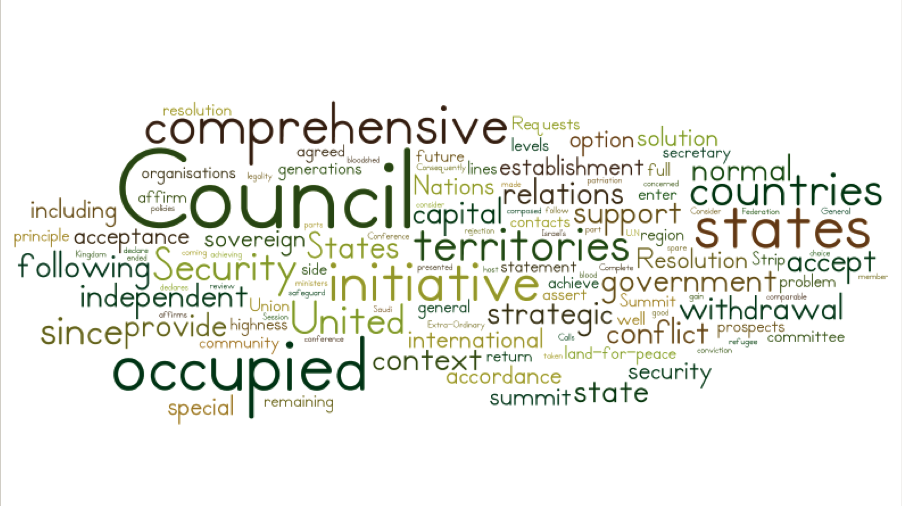

Obtain word frequencies of each bill section

Image source: khorn2.onmason.com/author/khorn2/

Measuring the enactment of a policy (cont.)

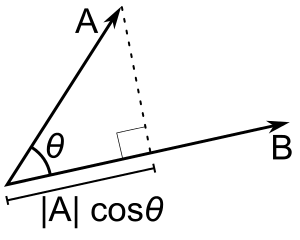

Treating word frequencies as a vector,

measure the angle between a pair of bill sections

Image source: www.mathsisfun.com/algebra/vectors-dot-product.html

Measuring the enactment of a policy (cont.)

if relative frequencies of all words are the same

if not a single word is used in common

Treat bill sections as the same policy if

Then look at the status of the last bill

among all bill sections dealing with one policy

Measuring the enactment of a policy (cont.)

Bills are typically amended throughout Congress session

| Status | # of policies | % of policies |

|---|---|---|

| Enacted | 45 | 8.4% |

| Reported | 106 | 19.7% |

| Not reported | 387 | 71.9% |

Source: Table 1 of Kang (2016)

Measuring lobbying expenditure

The lobbying industry data identify

559 firms and associations in the energy sector

Total lobbying expenditure: $607.9m

Median lobbying expenditure: $0.16m

Top 10% accounts for 76% of total expenditure

Source: Kang (2016), page 273

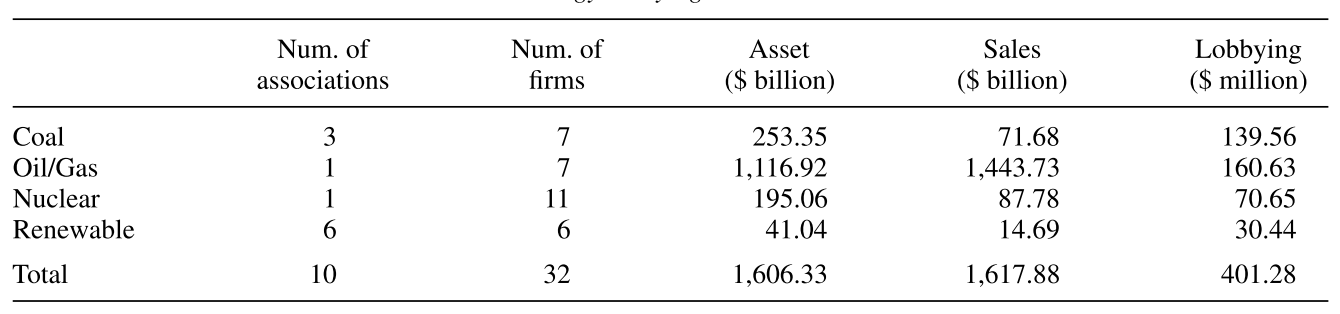

Measuring lobbying expenditure (cont.)

Source: Table 2 of Kang (2016)

Group these lobbying firms into four sub-sectors

Coal

Oil/Natural Gas

Nuclear

Renewable energy

Measuring which policy was lobbied

Assume a coalition lobbies for/against all policies within a bill mentioned in the dataset

% of policies each lobbying coalition participates in lobbying

| Coal | 50% |

| Oil / Natural Gas | 67% |

| Nuclear | 49% |

| Renewable | 62% |

Source: Table 3 of Kang (2016)

How to obtain return to lobbying expenditure

Policy value

x

Enactment probability increase

-

Lobbying expense

Lobbying expense

Calculate

(Profit)

(Investment)

But we don't observe policy value or enactment probability

We use a model

1

Each coalition decides how much to spend on lobbying in favour of / against each policy

Let

denote the sum of spendings

by those in favour of / against the policy

and

Model (a simplified version)

2

The policy is enacted with probability:

Policy enactment probability

if no lobbying spendings on either side

even if only those in favour lobby

The more spending, the less change in probability

Extra benefit from additional spending

spending

Extra benefit

Policy enactment probability

doesn't go up much

if you have spent a lot

Extra benefit from additional spending

spending

Extra benefit

Extra benefit goes up

if the value of a policy is higher

Optimization

spending ($)

Extra benefit

$1

More valuable policy

Less valuable policy

Spend more

for more valuable policy

Estimate policy enactment probabilities

Calculate

for a certain values of

Obtain the average for enacted policies and not-enacted policies

Repeat this for all possible values of

(roughly speaking)

Pick

that maximizes

See how higher the average for enacted policies is ( )

Estimated increase in enactment probability

only 0.054 percentage points

higher than in the absence of any lobbying

Source: page 287 of Kang (2016)

Estimated average value of policies

| Coal | $802.3m |

| Oil & Gas | $823.5m |

| Nuclear | $522.1m |

| Renewable | $549.0m |

Source: Table 13 of Kang (2016)

Return to lobbying expense

Policy value

x

Enactment probability increase

-

Lobbying expense

Lobbying expense

Calculate

(Profit)

(Investment)

Estimated return to lobbying expense

| Coal | 145.8% |

| Oil & Gas | 151.9% |

| Nuclear | 139.2% |

| Renewable | 137.0% |

Source: Table 13 of Kang (2016)

Today's Road Map

Campaign contributions versus lobbyists

Return to hiring lobbyists

Connection or expertise?

Where does the value of lobbyists come from?

Lobbyists are valuable potentially for two reasons

They help clients to contact politicians they used to work with

Their working experience help clients to deal with the inner workings of legislative process or policy matters

Connections

Expertise

Testing the

Connection hypothesis

Revolving Door Phenomenon in U.S.

Federal public employees often join the lobbying industry

56% of revenues by lobbying firms attribute to them

34 of top 50 lobbyists worked in the federal govt

cf. In US, 4,000+ top positions in federal government are appointed by President (1,000 of which requires the approval by the Senate)

Source: Table 1 of Blanes i Vidal et al. (2012)

Measuring lobbyists' connection

Identify lobbyists who used to work for congressmen

US congressmen can hire staffers with public money

Representatives / Senators hire 14 / 34 staffers on average

cf. MPs in Japan can hire only 3 staffers with public money

Estimate the value of connections

Check if the revenue is higher for those lobbyists with connections than for those without

Lobbyist's revenue = Value of their service to clients

Naive idea

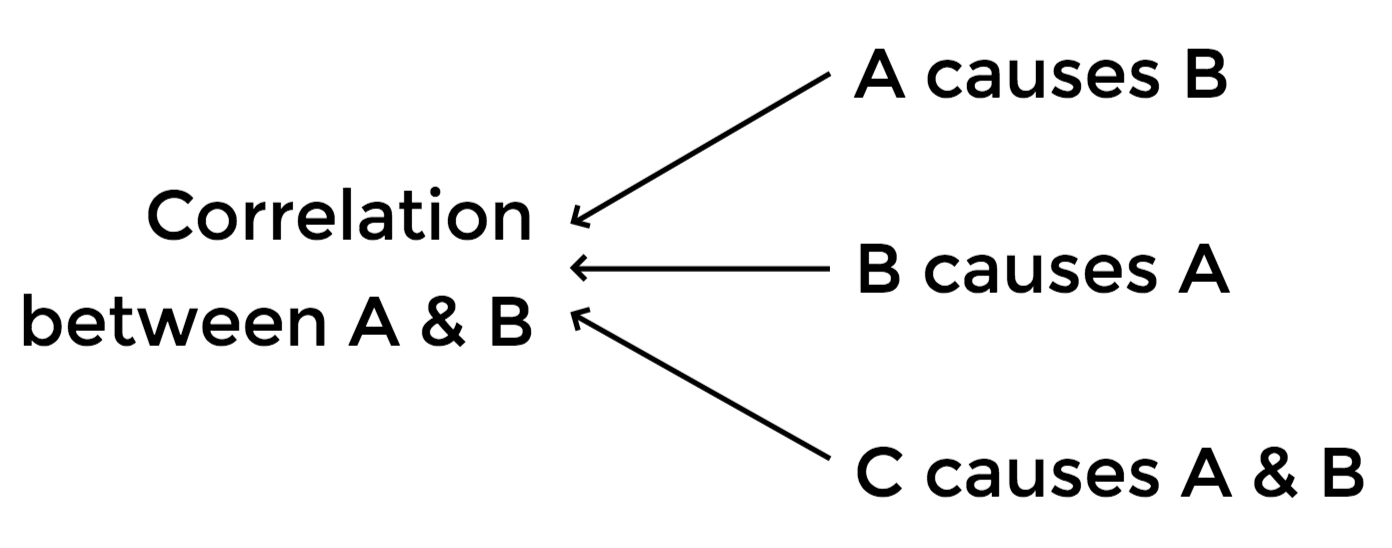

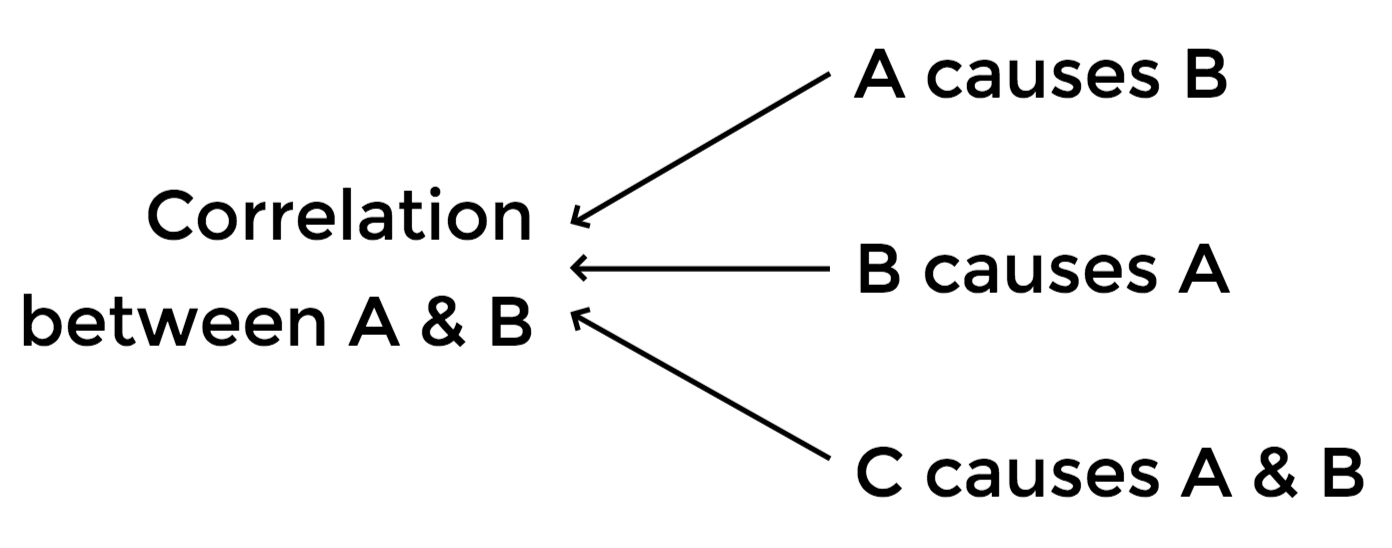

Estimate the value of connections (cont.)

But skilful lobbyists may have more connections

Skill

Connection

Revenue

Compare the biannual revenue of lobbyists

before and after their connected legislators leave office

Lobbyists' skill change

over time

Better idea

Their connected legislators'

decision to quit

unlikely

Estimate the value of connections (cont.)

Estimate the value of connections (cont.)

But macroeconomy may still affect both

Macroeconomy

Legislator leaving office

Revenue

Even better idea

Difference-in-differences (cf. Lecture 11)

| Before legislator quits | After legislator quits | |

| Connected lobbyist | A | B |

| Unconnected lobbyist | C | D |

Value of connections

= (A - B) - (C - D)

Estimate the value of connections (cont.)

Estimated value of connections to Senator

Source: Table 2 and page 3741 of Blanes i Vidal et al. (2012)

24% of the revenue of unconnected lobbyists

$372,000 per year on average

Testing the

Expertise hypothesis

Measuring lobbyists' expertise

From the lobbying industry data:

Obtain the share of revenues each lobbyist earns by policy issue

1/4 of lobbyists are specialists, defined this way

Those with political experiences are less likely to be specialists

If this share is 25% or more, we call this lobbyist a specialist

Source: Bertrand et al. (2014), pp. 3897-3900

Models of lobbying as information transmission

Two lobbyists with opposing ideology bias

They know what policy benefits society

Which may be against their ideology

The policy-maker does not know which policy is good

Lobbyists inform the policy-maker of which policy is good

They can tell a lie

Main prediction from these models

Policy-makers will learn the truth

when both lobbyists inform the policy-maker

If they tell different stories,

the policy-maker has an incentive to verify

This in turn gives an incentive for lobbyists to tell the truth

Main prediction from these models (cont.)

If lobbyists offer their expertise,

we should observe politicians listen to lobbyists from both camps

Evidence for the expertise view

For each congressman

identify which lobbyists they receive contributions from

This share should be higher for specialist lobbyists

if their expertise does matter

Obtain the share of such lobbyists from the other party

Separately for specialists and non-specialists

Evidence for the expertise view (cont.)

Share of lobbyists from the other party

Among non-specialists

Among specialists

28%

17%

Source: Table 7 of Bertrand et al. (2014)

Summary

Campaign contributions do not seem to affect policy-making per se

Lobbying does not change the enactment probability much

but the value of policies at stake is very large

so the return to lobbying expenditure is over 100%

The role of lobbyists appears to be both

1. Introducing connected politicians to their clients

2. Helping politicians with their expertise on policy issues

Next week...

Wars

Does poverty intensify civil wars?

What makes a war unavoidable?

This lecture is based on the following academic articles:

Kang, Karam. 2016. “Policy Influence and Private Returns from Lobbying in the Energy Sector.” The Review of Economic Studies 83(1): 269–305.

Bertrand, Marianne, Matilde Bombardini, and Francesco Trebbi. 2014. “Is It Whom You Know or What You Know? An Empirical Assessment of the Lobbying Process.” American Economic Review 104(12): 3885–3920.

Blanes i Vidal, Jordi, Mirko Draca, and Christian Fons-Rosen. 2012. “Revolving Door Lobbyists.” American Economic Review 102(7): 3731–48.

Ansolabehere, Stephen, John M De Figueiredo, and James M Snyder. 2003. “Why Is There so Little Money in U.S. Politics?” Journal of Economic Perspectives 17(1): 105–30.