My Attempt at Monads

Leon Tager

Zhia Chong

Software Engineer

Medium Blogger

(bit.ly/zhiastory)

Goals

Learn about

- Semigroup

- Monoids

- Functors

- Monoids

In a Explain-to-a-5-year-old manner

How did we get here?

☑ Immutable code

☑ Composing functions

☑ Higher order functions

☑ Currying

☑Recursion

At the start

Summingbird

Streaming MapReduce with Scalding and Storm

Monoids?

Scala

Lightweight, modular, and extensible library for functional programming

Monads?

Help!

infixl 1 >>, >>=

class Monad m where

(>>=) :: m a -> (a -> m b) -> m b

(>>) :: m a -> m b -> m b

return :: a -> m a

fail :: String -> m a

m >> k = m >>= \_ -> kThis doesn't help

functor

Alt

Plus

Alternative

Apply

Applicative

Monad

Bifunctor

Extend

Comond

Profunctor

Traversable

Foldable

Semigroupoid

Category

Setoid

Ord

Contravariant

Filterable

Semigroup

Monoid

Group

functor

Monad

Semigroup

Monoid

Semigroups

It's just an operation

Semigroups

It's just an operation

Semigroups - what is it?

// here's our definition of a semigroup

trait Semigroup[A] {

// some binary operation for you to define

def op(x: A, y: A): A

}

And...

Semigroup rules

Associativity - order of operation doesn't matter

// (1 + 2) + 3 = 1 + (2 + 3)

op(x, op(y, z)) = op(op(x, y), z)Closure - operation on members of a set always makes a member of the same set

// (A, A) -> A

def op(x: A, y: A): AExamples of Semigroup

val intMaxSemigroup: Semigroup[Int] = new Semigroup[Int] {

def op(x: Int, y: Int): Int = math.max(x, y)

}val intMinSemigroup: Semigroup[Int] = new Semigroup[Int] {

def op(x: Int, y: Int): Int = math.min(x, y)

}val list = Seq(1, 2, 3)

list.reduce(intMaxSemigroup.op) // 3

list.reduce(intMinSemigroup.op) // 1// But what will happen here?

val list = List.empty[Int]

list.reduce(intMaxSemigroup.op)java.lang.UnsupportedOperationException: empty.reduceLeft

at scala.collection.LinearSeqOptimized.reduceLeft(scratch_10.scala:131)

at scala.collection.LinearSeqOptimized.reduceLeft$(scratch_10.scala:130)

at scala.collection.immutable.List.reduceLeft(scratch_10.scala:82)

at scala.collection.TraversableOnce.reduce(scratch_10.scala:204)

at scala.collection.TraversableOnce.reduce$(scratch_10.scala:204)

at scala.collection.AbstractTraversable.reduce(scratch_10.scala:100)

at #worksheet#.get$$instance$$res0(scratch_10.scala:19)

at #worksheet#.#worksheet#(scratch_10.scala:51)// here's our definition of a semigroup

trait Semigroup[A] {

// an associative operation

def op(x: A, y: A): A

}

// Subtraction is not associative

scala> ((1 - 2) - 3)

res0: Int = -4

scala> (1 - (2 - 3))

res1: Int = 2Examples of a non-Semigroup

Semigroup

Do stuff to two things

Monoids

It's just an operation with a default

Monoids

It's just an operation with a default

Monoids - what is it?

// Monoid, like a semigroup is a definition of an operation

// with an identity value

trait Monoid[A] {

def op(a1: A, a2: A): A

def empty: A

}And...

Monoid rules

Associativity - order of operation doesn't matter

// (1 + 2) + 3 = 1 + (2 + 3)

op(x, op(y, z)) = op(op(x, y), z)Closure - operation on members of a set always makes a member of the same set

// (A, A) -> A

def op(x: A, y: A): AIdentity

// 1 + 0 = 0 + 1 = 1

op(x, id) == op(id, x) == xFamiliar?

If op meets the rules on type M then we say M forms a monoid under op.

Terminology

If addition meets the rules on type natural numbers then we say natural numbers form a monoid under addition.

Examples of a monoid

// but wait, there's more

trait Monoid[A] extends Semigroup[A] {

def empty: A

}val stringMonoid = new Monoid[String] {

def op(a1: String, a2: String) = a1 + a2

def empty = ""

}val intMultiplication = new Monoid[Int] {

def op(x: Int, y: Int) = x * y

val empty = 1

}val list = Seq(1, 2, 3)

list.foldLeft(intMultiplication.empty)(intMultiplication.op) // 6

val emptyList = List.empty[Int]

emptyList.foldLeft(intMultiplication.empty)(intMultiplication.op) // 1Much better

// here's our definition of a monoid

trait Monoid[A] {

// an associative operation

def op(a1: A, a2: A): A

// an identity element

def empty: A

}Monoid

semigroup with an identity

Monoids

Semigroup

Monoid - in other words

Monoid -why should I care?

Closure, Associativity and Identity

Monoids are everywhere.

-

Thanks to closure, we can combine and aggregate things.

-

Thanks to associativity, we can do it in parallel.

-

Thanks to identity, we know what to do when we don't have anything to start off with.

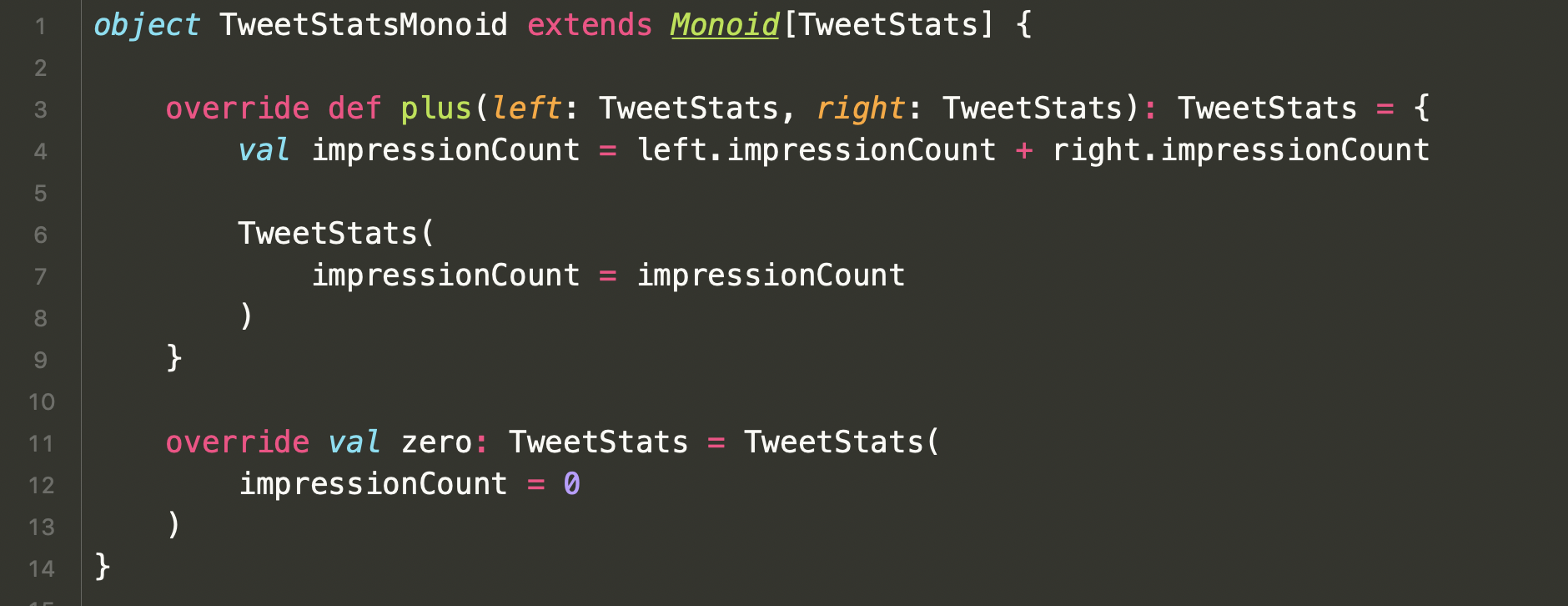

Monoid - How we use it at Twitter

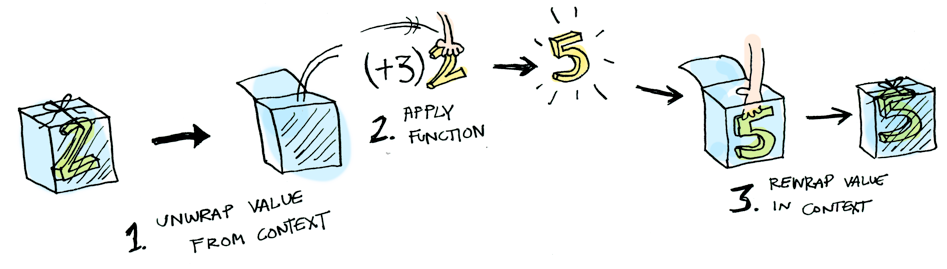

Functors

Take this and turn it into that

Functors - what is it?

Functors - what is it?

// It's a wrapper

trait Functor[F[_]] {

// It has a map method

def map[A,B](fa: F[A])(f: A => B): F[B]

}And...

Functor rules

Composition

// Mapping with g and then f is the same as

// Mapping both at the same time.

functor.map(g).map(f) == functor.map(x => f(g(x)))Identity

// passing the identity function

// returns the same functor back

// (in the mathematical sense)

functor.map(x => x) == functor// Example for an option

// (Basically the same old option.map)

val functorForOption: Functor[Option] = new Functor[Option] {

def map[A, B](fa: Option[A])(f: A => B): Option[B] = fa match {

case None => None

case Some(a) => Some(f(a))

}

}

val option = Option(1)

functorForOption.map(option)(a => a + 1) // Option(2)// definition of a functor

trait Functor[F[_]] {

// It has a map method

def map[A,B](fa: F[A])(f: A => B): F[B]

}Examples of functors

Examples of non-functors

// Breaks the identity law

val notAFunctor: Functor[List] = new Functor[List] {

def map[A, B](fa: List[A])(f: A => B): List[B] = fa match {

case _ => List.empty[B]

}

}val list = List(1, 2, 3)

notAFunctor.map(list)(x => x) // res1: List[Int] = List()Examples of non-functors

// Breaks the composition law

val notAFunctor2: Functor[Option] = new Functor[Option] {

var prop = 0

def map[A, B](fa: Option[A])(f: A => B): Option[B] = fa match {

case None => None

case Some(a) => {

prop += 1

if (prop == 1) Some(f(a)) else None

}

}

}val f: Int => Int = x => x + 1

val g: Int => Int = y => y + 2notAFunctor2.map(Option(1))(z => f(g(z))) //Option[Int] = Some(4)notAFunctor2.map(

notAFunctor2.map(Option(1))(g)

)(f) // None :-(Functor in pictures

Monads

Take this and turn it into that ++

Monads - what is it?

Monads - what is it?

And...

// It's a wrapper

trait Monad[F[_]] {

// It has two methods

def unit[A](a: => A): F[A]

def flatMap[A, B](ma: F[A])(f: A => F[B]): F[B]

}Monad rules

Associative

// Mapping with f and then g is the same as

// Mapping both at the same time.

x.flatMap(f).flatMap(g) == x.flatMap(a => f(a).flatMap(g))Identity

// Left identity

flatMap(x)(unit) == x// Right identity

flatMap(unit(y))(f) == f(y)Examples of monads

You already use them

- List

- Future*

- Option

- Try

- Either

Monads

Functors

Monads - in other words

Monad - use cases

def getUser(id: Long): Future[User]

def getHistory(user: User): Future[History]def getHistoryById(id: Long): Future[History] = getHistory(getUser(id))def getHistoryById(id: Long) = getUser(id) match {

case Success(user) => getHistory(user)

case Failure(_) => this.asInstanceOf[Future[S]]

}def getUser(id: Long): Option[User]

def getHistory(user: User): Option[History]def getHistoryById(id: Long) = getUser(id) match {

case Some(user) => getHistory(user)

case None => None

}Lists, Try, Either? This is going to be a long night

Monad - use cases

def getUser(id: Long): Future[User]

def getHistory(user: User): Future[History]def getHistoryById(id: Long): Future[History] = getUser(id).flatMap(getHistory)// Which is the same as

val res: Future[History] = for {

u <- getUser(0)

h <- getHistory(u)

} yield hMonads are great when evaluation of your function depends on the value of the previous function

Monad

Functor with a flatMap

Monad - fun fact

Functors compose. Monads don't

// Have you ever had to deal with

Option[List[A]]// Have you ever tried to map over it?

optionalList.map(_.map(f))Turns out that if F and G are functors, so is F[G[_]] for any functor

Composition of monads does not guarantee the result is a monad.

Things that confused me

Sometimes it's map, sometimes it's >>

Sometimes it's flatMap, sometimes it's join

Sometimes it's flatMap, sometimes it's join

trait Monad[F[_]] {

def unit[A](a: => A): F[A]

def flatMap[A, B](ma: F[A])(f: A => F[B]): F[B]

}trait Monad[F[_]] {

def unit[A](a: => A): F[A]

def map[A,B](fa: F[A])(f: A => B): F[B]

def join[A](fa: F[F[A]]): F[A]

}trait Monad[F[_]] {

def unit[A](a: => A): F[A]

// Composing Kleisli arrows

def compose[A,B,C](f: A => F[B], g: B => F[C]): A => F[C]

}A monad needs to satisfy the rules mentioned earlier - associativity and identity. The interface is not important.

I can't find any of these interfaces in Scala

Summary of key points

| Semigroup | An operation on two objects | op: (A, A) -> A |

| Monoid | A an operation with a default | op: (A, A) -> A identity: A |

| Functor | Something that can be mapped over | map F[A] ->(A -> B): F[B] |

| Monad | A functor that unwrapes the top layer | flatMap F[A] -> (A -> F[B]): F[B] |

A monad is just a monoid in the category of endofunctors, what's the problem?

Thank you