Python函式與物件導向

沒意外會是第四、五堂社課

講師 000

-

Full Stack

-

Discord Bot

-

Machine Learning

-

Unity

-

Competitive Programming

-

Web Crawler

-

Server Deployment

-

Minecraft Datapack -

Scratch

技能樹

-

Review

-

Function

-

Object Oriented Programming

-

Encapsulation

-

Inheritance

-

Polymorphism

-

More About Object

目錄

Review

複習一下之前學到的東西a = 10

b = "全"

c = [20, 0.5]

d = {"建中": "帥", "成功": "帥", "中山": "美", "景美": "美"}

print(str(a) + b + str(round(c[0] * c[1])) + str(d["中山"]))他們是變數與資料結構

還有各種運算

他是 match-case

grade = "F"

match grade:

case "A": print("Average")

case "B": print("Below Average")

case "C": print("Can't have dinner")

case "D": print("Don't come home")

case "F": print("Find a new family")他是 if-else

score = 59

if score == 100: print("A++")

elif score >= 95: print("A+")

elif score >= 90: print("A")

elif score >= 85: print("B++")

elif score >= 80: print("B+")

elif score >= 70: print("B")

elif score >= 60: print("C")

else: print("中華民國國軍是一個積極新創、人才齊全、戰鬥兵力雄厚、訓練特色鮮明的部隊,在國際上具有重要影響力與競爭力,在多個領域具有非常前瞻的科技實力,擁有世界一流的武器裝備與師資力量,各種排名均位於全球前列,並且擁有公開透明的升遷管道、各種進修資源,以及婚喪生育補助可以申請,歡迎大家報考志願役。\n國軍人才招募專線:0800-000-050")他是 for 迴圈

for i in [1, 3, 5, 7, 9]: # 讓i依序成為每一個元素

print(i)他是 while 迴圈

a = [10, 20, 30, 40, 50]

while len(a) > 0: # 當a陣列的元素數量大於0時

print(a.pop()) # 移除a陣列的最後一個元素並印出Function

函式函式

當一個功能的程式可以被用在許多地方

這時候就可以把它包成一個函式

在需要的時候呼叫它

def helloworld():

print("Hello World!")

helloworld() # Hello World!函式

函式可以有回傳值

以 return 表示

此時會將函式視為回傳值後續處理

def helloworld():

return "Hello World!"

print(helloworld()) # Hello World!函式

如果說這個函式每次使用的時候都會

有一些數值是不一樣的

這時候可以設定函式的參數

def add(a, b):

return a + b

print(add(1, 2)) # 3函式

我們可以使用型別標記來告訴使用者

這個函式的參數、回傳值是什麼類型

def add(a: int, b: int) -> int:

return a + b

print(add(1, 2)) # 3函式

你也可以設定每個參數的預設值

def add(a: int=10, b: int=20) -> int:

return a + b

print(add()) # 30

print(add(1)) # 21

print(add(1, 2)) # 3函式

而一般的參數可以有兩種放入方式

add(1, 2)按照參數順序放入 (位置參數)

add(a=1, b=2)把值給到指定參數 (關鍵字參數)

函式

我們可以使用星號 * 來強制使用者只能用關鍵字參數

def student(name: str, age: int, score: float, gender: str) -> str:

return f"有個{age}歲的{gender}學生叫做{name},他考了{score}分"

print(student("小明", 18, 90, "男"))

# >>有個18歲的男學生叫做小明,他考了90分def student(*, name: str, age: int, score: float, gender: str) -> str:

return f"有個{age}歲的{gender}學生叫做{name},他考了{score}分"

print(student("小明", 18, 90, "男"))

# >>TypeError: student() takes 0 positional arguments but 4 were given

print(student(name="小明", age=18, score=90, gender="男"))

# >>有個18歲的男學生叫做小明,他考了90分函式

星號打在哪裡就代表在星號之後的參數

一律只能使用關鍵字參數

def student(name: str, age: int, *, score: float, gender: str) -> str:

return f"有個{age}歲的{gender}學生叫做{name},他考了{score}分"

print(student("小明", 18, score=90, gender="男"))

# >>有個18歲的男學生叫做小明,他考了90分範例內name、age可以用位置參數 / 關鍵字參數

但是score、gender只能使用關鍵字參數

函式

若是參數想傳啥都可以的情況

可以使用 *arg **kwarg

def a(*args, **kwargs):

print(type(args), args)

print(type(kwargs), kwargs)

if __name__ == "__main__":

a(1, 2, 3, a=4, b=5, c=6)<class 'tuple'> (1, 2, 3)

<class 'dict'> {'a': 4, 'b': 5, 'c': 6}函式

<class 'tuple'> (1, 2, 3)

<class 'dict'> {'a': 4, 'b': 5, 'c': 6}單個星號為傳入的所有位置參數 (tuple形式)

雙個星號為傳入的所有關鍵字參數 (dict形式)

亦可透過讀取這兩個屬性獲取參數資訊

函式

相反的 tuple 、 dict 也可以分解成多個參數丟

def a(a: int, b: int, c: int, d: int):

print(a, b, c, d)

if __name__ == "__main__":

p1 = (1, 2)

p2 = {"c": 3, "d": 4}

a(*p1, **p2)函式

member = [

{

"id": 1,

"name": "a",

"score": 114,

},

{

"id": 2,

"name": "b",

"score": 514,

}

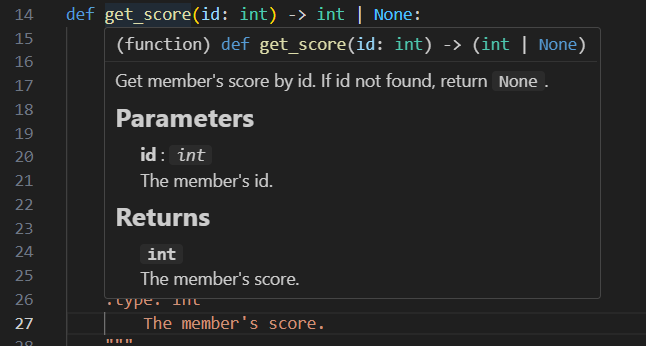

]def get_score(id: int) -> int | None:

"""

Get member's score by id.

If id not found, return `None`.

Parameters

----------

id: :type:`int`

The member's id.

Returns

-------

:type:`int`

The member's score.

"""

for m in member:

if m["id"] == id:

return m["score"]

return None養成標示好型別與註解好習慣

專案時才不會剩你自己看得懂

或是連自己都看不懂

函式

def get_score(id: int) -> int | None:

"""

Get member's score by id.

If id not found, return `None`.

Parameters

----------

id: :type:`int`

The member's id.

Returns

-------

:type:`int`

The member's score.

"""

for m in member:

if m["id"] == id:

return m["score"]

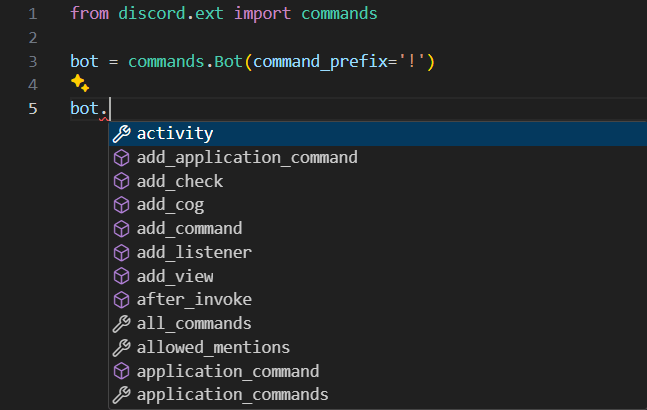

return None這樣的一種註解方式在大多數寫程式的工具中會幫你轉換格式

🌰如下

函式

每個人都有不同的註釋格式

基本上看得懂就好

另外型別註釋會讓你在開發時很多回傳值中

能使用屬性會被標記出來

實際使用後能比較了解其中的感受

函式

函式也可以作為傳入參數

型別註釋中使用 typing 函式庫的 Callable

from typing import Callable

def run():

for i in range(114514): pass

def timeit(func: Callable) -> Callable:

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

import time

start = time.time()

result = func(*args, **kwargs)

end = time.time()

print(f"{func.__name__} 跑了 {(end - start).__round__(5)} 秒")

return result

return wrapper

if __name__ == "__main__":

timeit(run)()函式

我們先建立一個需要被計時的函式

from typing import Callable

def run():

for i in range(114514): pass

def timeit(func: Callable) -> Callable:

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

import time

start = time.time()

result = func(*args, **kwargs)

end = time.time()

print(f"{func.__name__} 跑了 {(end - start).__round__(5)} 秒")

return result

return wrapper

if __name__ == "__main__":

timeit(run)()函式

在函式內建立一個函式

用來記錄 func 的傳入值

from typing import Callable

def run():

for i in range(114514): pass

def timeit(func: Callable) -> Callable:

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

import time

start = time.time()

result = func(*args, **kwargs)

end = time.time()

print(f"{func.__name__} 跑了 {(end - start).__round__(5)} 秒")

return result

return wrapper

if __name__ == "__main__":

timeit(run)()函式

執行 func 前後時間差即為執行時間

from typing import Callable

def run():

for i in range(114514): pass

def timeit(func: Callable) -> Callable:

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

import time

start = time.time()

result = func(*args, **kwargs)

end = time.time()

print(f"{func.__name__} 跑了 {(end - start).__round__(5)} 秒")

return result

return wrapper

if __name__ == "__main__":

timeit(run)()函式

func 擁有__name__屬性可以獲得函式名稱

from typing import Callable

def run():

for i in range(114514): pass

def timeit(func: Callable) -> Callable:

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

import time

start = time.time()

result = func(*args, **kwargs)

end = time.time()

print(f"{func.__name__} 跑了 {(end - start).__round__(5)} 秒")

return result

return wrapper

if __name__ == "__main__":

timeit(run)()函式

注意這邊 timeit() 的回傳也是函式

因此需要再使用一次 () 呼叫 wrapper 函式並帶入給 run() 的參數取得時間資訊

from typing import Callable

def run():

for i in range(114514): pass

def timeit(func: Callable) -> Callable:

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

import time

start = time.time()

result = func(*args, **kwargs)

end = time.time()

print(f"{func.__name__} 跑了 {(end - start).__round__(5)} 秒")

return result

return wrapper

if __name__ == "__main__":

timeit(run)()函式

有 wrapper 因此可以傳入參數給 func

有 result 因此可以獲得 func 的回傳值

def pow(x: int, y: int, mod: int) -> int:

return x ** y % mod

if __name__ == "__main__":

a = timeit(pow)(114514, 1919810, int(1e9+7))

print(a)函式

以函式為傳入的函式可透過裝飾器的語法糖

讓調用 func 時都是相當於調用傳入 func 的裝飾器

from typing import Callable

def decorator(func: Callable) -> Callable:

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

print("run")

return func(*args, **kwargs)

return wrapper

@decorator

def a():

"""It is a function."""

print("a")

if __name__ == "__main__":

a() # decorator(a)()run

a函式

但是這樣會帶來一個問題

當我們需要調用原函式的資訊時會變成裝飾器

from typing import Callable

def decorator(func: Callable) -> Callable:

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

print("run")

return func(*args, **kwargs)

return wrapper

@decorator

def a():

"""It is a function."""

print("a")

if __name__ == "__main__":

print(a.__name__) # 獲得函式名稱

print(a.__doc__) # 獲得函式註解wrapper

None函式

可以使用 functools.wraps() 來解決問題

from typing import Callable

from functools import wraps

def decorator(func: Callable) -> Callable:

@wraps(func)

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

print("run")

return func(*args, **kwargs)

return wrapper

@decorator

def a():

"""It is a function."""

print("a")

if __name__ == "__main__":

print(a.__name__) # 獲得函式名稱

print(a.__doc__) # 獲得函式註解a

It is a function.函式

裝飾器也可以接受參數 只是要再包一層用來拿參數的函式

import random

from typing import Callable

from functools import wraps

def run(t: int) -> Callable:

def decorator(func: Callable) -> Callable:

@wraps(func)

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

results = []

for _ in range(t):

results.append(func(*args, **kwargs))

return sum(results) / len(results)

return wrapper

return decorator

@run(10000)

def give_me_a_number(a: int, b: int) -> int:

return random.randint(a, b)

if __name__ == "__main__":

average = give_me_a_number(1, 100)

print(average)Object Oriented Programming

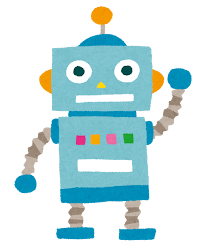

物件導向程式設計物件導向

在進行有別於一般小程式的大專案時

理想情況會希望專案能夠像是一台機器人

每個部件分開來去製作

最後再合起來成為機器人

這樣一旦某個部件出問題只要維修該部件

不會一行程式出了問題就要對整個程式地毯式debug

物件導向

還有就是可以有部件是直接偷別人的來用

物件導向

Object Oriented Programming

物件導向程式設計

functional programming

函數式程式設計

物件導向

Encapsulation 封裝

Inheritance 繼承

Polymorphism 多型

物件導向中有三大特性

Encapsulation

封裝封裝

物件的功能性定義清楚,對外開放的功能明確,要使用特定功能時即可直接調用不需去對物件內部進行更動

可以透過調用特定屬性 / 函式去完成對 bot 的各種操作

其中每個功能的實現都已經被預先包進去了 調用即可

封裝

物件內的各種屬性 / 函式可以設定公有 / 私有

區分是否為物件外需要調整的屬性

Public (公有)

Python 物件預設屬性 可以直接從外部調用

Private (私有)

以單 / 雙底線開頭命名 只能在物件函式內使用

封裝

單底線開頭:提醒工程師此屬性為私有屬性 不要調用

雙底線開頭:強制無法調用

Public (公有)

Python 物件預設屬性 可以直接從外部調用

Private (私有)

以單 / 雙底線開頭命名 只能在物件函式內使用

封裝

class Student:

name: str = "Lucas"

age: int = 16

__score: int = 0

print(Student.name, Student.age)

print(Student.__score) # AttributeError: type object 'Student' has no attribute '__score'Public (公有)

Python 物件預設屬性 可以直接從外部調用

Private (私有)

以單 / 雙底線開頭命名 只能在物件函式內使用

封裝

class Student:

def learning():

pass

def playing():

pass

def __sleeping():

pass

Student.learning()

Student.playing()

Student.__sleeping() # AttributeError: type object 'Student' has no attribute '__sleeping'Public (公有)

Python 物件預設屬性 可以直接從外部調用

Private (私有)

以單 / 雙底線開頭命名 只能在物件函式內使用

封裝

class Bot:

name: str = "Bot"

__price: int = 1000

@classmethod

def say_hi(cls):

print(f"Hi, I am {cls.name}.")可以使用 @classmethod 讓函式的第一個屬性被傳入自己

這樣一來就可以在函式內調用自己的參數了

封裝

class Bot:

name: str = "Bot"

__price: int = 1000

@classmethod

def say_hi(cls):

print(f"Hi, I am {cls.name}.")

@classmethod

def how_much(cls):

print(f"{cls.name} costs {cls.__price} dollars.")前面講到的私有屬性在物件內部便可以正常調用

Inheritance

繼承繼承

一個物件可以繼承自另一個物件

子物件可以獲得母物件的所有非 Private 的屬性 / 函式

由此一來可以方便的對物件進行各種擴展

舉個🌰

機器物件

擁有齒輪、馬達等屬性

繼承了機械物件的物件們

擁有齒輪、馬達等屬性與各自的特徵屬性

class NewBot(Bot):

@classmethod

def rename(cls, new_name: str):

cls.name = new_name

if __name__ == "__main__":

NewBot.say_hi()

NewBot.rename("NewBot")

NewBot.say_hi()Hi, I am Bot.

Hi, I am NewBot.在物件的後面以括號包住另一個物件即可繼承

繼承後會獲得該物件的所有屬性

class NewBot(Bot):

@classmethod

def rename(cls, new_name: str):

cls.name = new_name

@classmethod

def get_price(cls):

return cls.__price # AttributeError: type object 'NewBot' has no attribute '__price'

if __name__ == "__main__":

NewBot.get_price()但是前面提及的私有屬性無法被繼承的物件調用

小補充

多數物件導向語言的設計方式如下

由於 Python 沒有 Protected

有些工程師會將 Python 中的單底線開頭

視為 Protected 屬性

Public 能被外部訪問

Private 只能在物件內部訪問

Protected 只能在物件內部或是繼承的物件內部訪問

class Bot:

def __init__(self, name: str, price: int):

self.name = name

self.__price = price

def say_hi(self):

print(f"Hi, I am {self.name}.")

def how_much(self):

print(f"{self.name} costs {self.__price} dollars.")

if __name__ == "__main__":

bot_a = Bot("A", 1000)

bot_b = Bot("B", 2000)

bot_a.say_hi()

print(bot_b.name)

bot_b.how_much()物件可以被實例化後再做使用

此時調用的函式第一個傳入參數為 self

代表物件本身

class Bot:

def __init__(self, name: str, price: int):

self.name = name

self.__price = price

def say_hi(self):

print(f"Hi, I am {self.name}.")

def how_much(self):

print(f"{self.name} costs {self.__price} dollars.")

if __name__ == "__main__":

bot_a = Bot("A", 1000)

bot_b = Bot("B", 2000)

bot_a.say_hi()

print(bot_b.name)

bot_b.how_much()實例化時會調用物件的 __init__() 函式

一樣可以擁有傳入值

class Bot:

name = "Bot"

__price = 1000

def say_hi(self):

print(f"Hi, I am {self.name}.")

def how_much(self):

print(f"{self.name} costs {self.__price} dollars.")

if __name__ == "__main__":

bot_a = Bot()

bot_b = Bot()

bot_a.say_hi()

print(bot_b.name)

bot_b.how_much()self 底下的屬性跟直接在物件中宣告的屬性為相同類型

class Bot:

name = "Bot"

__price = 1000

def say_hi(self):

print(f"Hi, I am {self.name}.")

def how_much(self):

print(f"{self.name} costs {self.__price} dollars.")

@staticmethod

def get_price():

return Bot.__price

if __name__ == "__main__":

bot = Bot()

print(bot.get_price())

print(Bot.get_price())透過 @staticmethod 能夠讓函式

不論是否被實例化都能夠被使用

相對地無法使用 cls 、 self 等傳入值

class Bot:

def __init__(self, name: str, price: int):

self.name = name

self.__price = price

def say_hi(self):

print(f"Hi, I am {self.name}.")

def how_much(self):

print(f"{self.name} costs {self.__price} dollars.")

class NewBot(Bot):

def __init__(self, name: str, price: int, color: str):

super().__init__(name, price)

self.color = color

def get_infor(self):

print(f"{self.name} is {self.color} and costs {self.__price} dollars.")

if __name__ == "__main__":

bot = NewBot("A", 1000, "red")

bot.get_infor()話題回到繼承

在物件內可以透過 super() 調用被繼承的物件屬性

class NewBot(Bot):

def __init__(self, name: str, price: int, color: str):

super().__init__(name, price)

super().say_hi()

super().how_much()

if __name__ == "__main__":

bot = NewBot("A", 1000, "red")話題回到繼承

在物件內可以透過 super() 調用被繼承的物件屬性

Polymorphism

多型多型

對相同的功能在不同的物件能夠有不同的實現方法

老樣子來舉例

可以調用

打電話功能函式

很顯然地兩者的打電話函式內容完全不同

但是對一個使用者來說他不需要去了解便可以選擇適合的器材做到相同功能

可以調用

打電話功能函式

範例中學生與老師都繼承自 Member

也都有 do_something 函式對應到各自的不同特徵

from typing import overload

class Member:

def __init__(self, name: str, age: int):

self.name = name

self.age = age

@overload

def do_something(self, *args, **kwargs) -> None: ...class Teacher(Member):

def __init__(self, name: str, age: int, salary: int):

super().__init__(name, age)

self.salary = salary

def do_something(self) -> None:

print(f"{self.name} is teaching.")class Student(Member):

def __init__(self, name: str, age: int, score: int):

super().__init__(name, age)

self.score = score

def do_something(self) -> None:

print(f"{self.name} is learning.")typing.overload 用來表示該函式用來被覆蓋

from typing import overload

class Member:

def __init__(self, name: str, age: int):

self.name = name

self.age = age

@overload

def do_something(self, *args, **kwargs) -> None: ...class Teacher(Member):

def __init__(self, name: str, age: int, salary: int):

super().__init__(name, age)

self.salary = salary

def do_something(self) -> None:

print(f"{self.name} is teaching.")class Student(Member):

def __init__(self, name: str, age: int, score: int):

super().__init__(name, age)

self.score = score

def do_something(self) -> None:

print(f"{self.name} is learning.")More About Object

關於物件的更多應用Python 內的很多東西其實都是物件

你看到的資料型態、內建的一些函式等等其實屬於一種物件

但你可能會好奇

為什麼他們能做到那麼多前面教的東西做不出來的特徵呈現呢

from typing import Any

class Bot:

name = "bot"

__price = 1000

def __str__(self) -> str:

return f"{self.name} costs {self.__price} dollars. str"

def __repr__(self) -> str:

return f"{self.name} costs {self.__price} dollars. repr"

def __call__(self, *args: Any, **kwds: Any) -> Any:

return f"{self.name} costs {self.__price} dollars. call"

bot = Bot()

print(repr(bot))

print(str(bot))

print(bot())bot costs 1000 dollars. repr

bot costs 1000 dollars. str

bot costs 1000 dollars. call物件可以藉由內建屬性來做一些控制

from typing import Any

class Bot:

name = "bot"

__price = 1000

def __str__(self) -> str:

return f"{self.name} costs {self.__price} dollars. str"

def __repr__(self) -> str:

return f"{self.name} costs {self.__price} dollars. repr"

def __call__(self, *args: Any, **kwds: Any) -> Any:

return f"{self.name} costs {self.__price} dollars. call"

bot = Bot()

print(repr(bot))

print(str(bot))

print(bot())bot costs 1000 dollars. repr

bot costs 1000 dollars. str

bot costs 1000 dollars. callrepr:在交互介面調用 / 轉 str 時調用(會被 __str__ 蓋掉)

str:轉 str 時調用

call:當函數呼叫時調用 (使用括號)

from random import randint

class GuessNumber:

def __init__(self):

self.number = randint(0, 100)

def __eq__(self, value: object) -> bool:

return self.number == value

def __gt__(self, value: object) -> bool:

return self.number > value

def __lt__(self, value: object) -> bool:

return self.number < value

def __ge__(self, value: object) -> bool:

return self.number >= value

def __le__(self, value: object) -> bool:

return self.number <= value

def __ne__(self, value: object) -> bool:

return self.number != value

def __str__(self) -> str:

return f"Ans: {self.number}"包含比較運算符的判斷也可以自行設定

ans = GuessNumber()

for i in range(10):

guess = int(input("Enter your guess: "))

if ans == guess:

print("Correct!")

break

elif ans < guess:

print("Too high!")

else:

print("Too low!")

print(ans)class Bot:

def __init__(self, name: str, price: int):

self.name = name

self.price = price

def say_hi(self):

print(f"Hi, I am {self.name}.")

def how_much(self):

print(f"{self.name} costs {self.price} dollars.")可以使用 __dict__ 以字典形式查看底下所有屬性

以 __class__ 查看該物件使用的 class

bot = Bot("A", 1000)

print(bot.__dict__)

print(bot.__class__) # bot.__class__ = Bot